A Student With Mr. Gaddis

Jon Fain studied creative writing with William Gaddis at Bard College between 1976 and 1978, during Gaddis’s first university teaching job. It didn’t go perfectly, as Fain discusses in this retrospective, which includes a letter of Gaddis’s writing-feedback.

Various materials by William Gaddis, Copyright © 2024 The Estate of William Gaddis, used by permission of the Wylie Literary Agency (UK) Limited Due to the copyrighted material reproduced here, this article is published under a stricter version of open access than the usual Electronic Book Review article: a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 license. All reproductions of material published here must be cited; no part of the article or its quoted material may be reproduced for commercial purposes; and the materials may not be repurposed and recombined with other material except in direct academic citation – https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

I came late to reading The Letters of William Gaddis (ed. Steven Moore). My interest stemmed from being at Bard College when Mr. Gaddis—with his tailored suits, reserved demeanor and literary reputation this was how most everyone, including professors, referred to him—first arrived to join its faculty, in 1976.

I had gone to Bard because of its history of having writers such as Saul Bellow, Ralph Ellison, and Mary McCarthy on campus as distinguished visiting professors. The year before Mr. Gaddis arrived, I took a fiction workshop with Isaac Bashevis Singer. Mr. Gaddis was going to come and offer a writers’ workshop as well, and because his long-awaited second novel J R had just come out, this was a big deal. I read it the summer before taking his class, and liked the dialogue-driven approach, the humor, and the light he cast on the dark side of capitalism across a wide range of characters, within the mammoth world of yearning and striving he had created.

Reading his letters from that period, I recognized myself as part of the student cohort he described as not saying much and not writing much. To his correspondents, he questioned why they (we) were even there. In one letter, he suggested undergraduates shouldn’t be offered creative writing classes.

From the first workshop sessions, he talked about the third person as being the best vehicle for fiction.1 I was writing something in first person, and switched it to third. I wasn’t happy with it, or the tepid response it got from the class when I read it, so I rewrote it in first person and brought it back a couple of weeks later. Although Mr. Gaddis did admit it was better in first person, he was far from changing his preference. And, he probably knew I was challenging him to some extent. There was some tension between us after that.

For my senior project the following year, the Fall of 1977, I was going to make my first attempt at a novel. When the time came for me to choose a faculty advisor, it turned out Bard’s primary professor of fiction writing, Peter Sourian, who I’d taken multiple workshops with, was going to be on sabbatical during the fall semester. Mr. Gaddis and I ended up assigned to one another after an awkward interaction during pre-registration when Professor Sourian had to talk him into it, with me waiting in front of the table where they were sitting.

“No, no, he’s good,” I want to recall Professor Sourian saying. I do remember Mr. Gaddis looking skeptically at me. No doubt based on what he had seen in the workshop, he was right to be dubious. Professor Sourian had a way of getting uncomfortably close when he talked to you. Maybe Mr. Gaddis shrugged his agreement to get Sourian to back off.

Although I knew that having an accomplished novelist of his stature as an advisor was unique, and a situation foolish to pass up, I was intimidated by the prospect, especially because we hadn’t hit it off in class.

Once the new semester began, we started with our weekly meetings. I don’t remember for sure, but I suspect I chose to write my novel in the third person because of his strong preference for it, finally giving in. I do remember that soon after I began, I recognized how much harder and more challenging writing a novel was going to be than a collection of stories; I mean, I’d assumed as much, but now I knew. I had come to Bard thinking my senior project was going to be some great debut novel that would send me on my literary way. Right away, I was struggling to get through a first draft.

One time when I came into our meeting with no new pages to show him we sat without talking. Mr. Gaddis then shared a story about how Emerson and Thoreau used to get together and sit in a comfortable silence for hours in front of the fireplace, remarking about our situation, “That is not the case here.” I left to go and sit in front of my typewriter, by myself. My wife, also a student at Bard, had him as a senior project advisor a couple of years later. She was/is much savvier than me; when she didn’t have anything to show him, she brought in a copy of Nathanael West’s Miss Lonelyhearts, and they took turns reading favorite passages to each other.

While he could be somewhat distant during our meetings, he did provide encouragement and acknowledged a familiarity with my struggles. Part of the difficulty with being a young fiction writer, he said, was having limited experiences; as an older writer, he had “more stuff” in his memory to draw upon. Still, I needed to bring in more work!

Many of his letters of that period mention Joan Didion’s short novel, Play It As It Lays, that he recommended often, as he did to me, for its precise, spare language, and how she keeps things moving. I found other letters from his “Bard years” interesting as well. He seemed to enjoy teaching there more as the years went on, in one letter writing how he’d turned down an offer from Bennington to stay where he was; he was amused that the other college offered him much less money than “little Bard” was paying him.

Another interesting aspect of reading his letters is that it filled out the picture of his personal life at the time. When other students asked me what he was like, I referred to him as a “haunted dude.” Now I know he was dealing with his second wife leaving him, and concerns about his kids. He did share with me once that he was having difficulties deciding on what to work on next, mentioning “a Civil War play.” I learned from the letters that it was a longtime project of interest—I already knew, from reading A Frolic of His Own, where it found its final form.

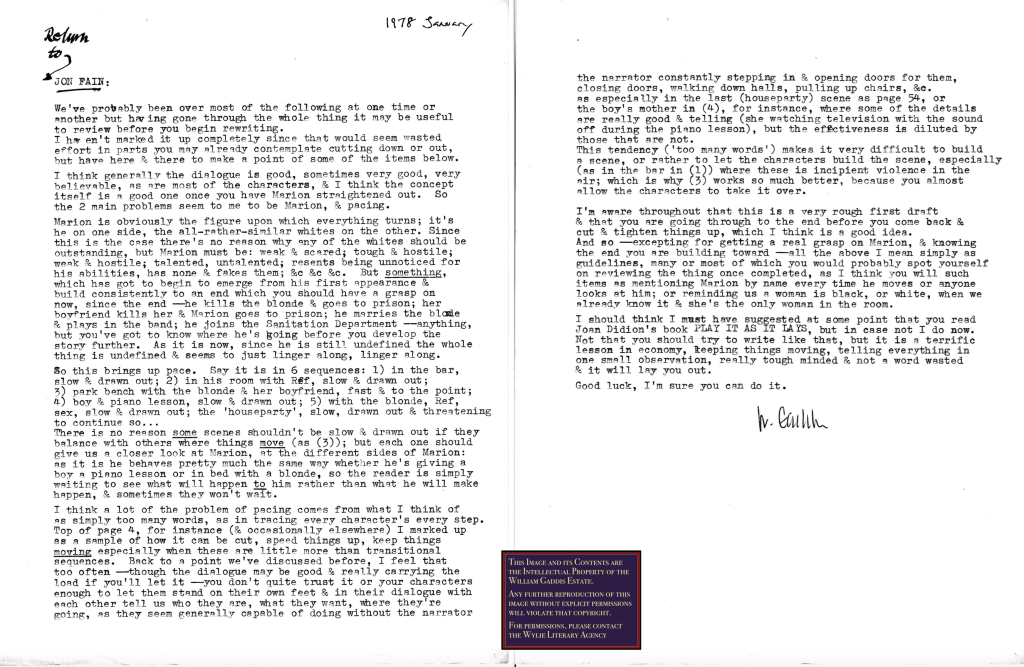

I have a pair of letters he wrote to me. One is his end-of-semester critique and advice, the highlight for me being that he found some of the dialogue in the work “very good, very believable” (see Figure 1). But it needed to advance the action, it needed to do more than just hint at things to come. There had to be some payoff, revelations that mattered. In the letter, the main encouragement he had was to create meaningful action, a steady pace. I was getting stalled in the set-up of scenes, not getting enough out of them, focusing too much on the physical movement of characters from room to room, place to place. Nothing important was happening.

I didn’t complete a first draft that semester, and during the month-long break in January I decided to start over again. This was before I returned to school and discovered the letter from Mr. Gaddis, which was more than I expected I’d be getting from him. Professor Sourian tried to talk me out of a rewrite, advising that I should follow Mr. Gaddis’s prompts and work with what I had. But I was committed to going in a different direction. I remember telling him my goal was to get more experience writing a novel, learning through the process, less concerned with what I could come up with as a “final” product by the end of the semester. I had no interest in going to graduate school, so I didn’t care much about the grade. I wanted to get out of school and start acquiring the “more stuff” that Mr. Gaddis had referred to.

The end result was not impressive. No literary agent was going to be waiting for me offstage after I’d been handed my diploma. In his comments on my grade sheet Professor Sourian suggested I’d tried to do too much, that I’d been “overly ambitious” in what I’d attempted, that it may have been a better choice to build on my earlier stories to create a collection before I tried a novel. It’s possible, if he hadn’t been on sabbatical, that’s what I would have done. Regardless, I always thought Mr. Gaddis would have been amused at anyone describing me at that time as being “overly ambitious.”

The other letter I have from him is from 1983. Post-Bard, after putting it aside for a few years, I’d re-written the novel again and I’d contacted him, probably through his publisher, to ask if he had any advice. He was kind enough to write back and say I could send it to his agent, Candida Donadio, who told him she would look at it, but there were no guarantees. (And no interest.)

Since then I’ve written another four novels, and while I had an agent helping me market one of them, they’re all unpublished. But I’ve had close to a hundred short fiction pieces published over the years, starting in men’s magazines in the mid-80s, and more recently, among the many literary websites that began to appear in the early 2000s, up to the present. I don’t know if Mr. Gaddis would have been surprised or not that I’ve kept at, with various stops and starts along the way.

Now, because I’m twelve years older than Mr. Gaddis was when we sat together in his office trying to make a connection, I can rely on the “more stuff” in my head. I have learned that writing fiction is even harder than I’d thought. A journey that is as good an excuse as any to look a bit haunted now and then.

Footnotes

-

I don’t remember what his stated reasons were: I always connected it to his strong stand on writers not putting themselves out there, rather letting the work stand on its own. So he didn’t want an autograph photo, and he didn’t want to have to explain anything about the work. There’s that sketch he did of himself for a compilation book of writers who asked to do self-portraits, and his is just a torso in a suit, holding a cocktail. It became the cover image of the first published collection of essays about him. ↩

Cite this essay

Fain, Jon. "A Student With Mr. Gaddis" Electronic Book Review, 7 April 2024, https://doi.org/10.7273/ebr-gadcent6-3