Advertising with AI – On the presentation of authorship of ChatGPT-generated books

Tuuli Hongisto explores the problems of cyborg authorship through the presentation of ChatGPT as a co-author of literary works on Amazon. Rather than shying away from admitting that an AI took part in the writing process, these authors position ChatGPT and other LLM's as authors with their own rights, rather than tools.

The thought of a machine writing poetry and fiction has fascinated people for centuries.1 With each technological advancement that enables new methods of text generation, the idea of machine authorship resurfaces as a public discussion. Such is also the case with the latest, and purportedly the greatest, development in text generation: large language models (LLMs) and the programs based on them. In this article, the discussion of computer authorship is approached through a medium whence the conception of author as a singular identifiable creator largely stems from: published books.

The research material consists of descriptions and other metadata on books published under the category of “Literature & Fiction” on Amazon that have marked ChatGPT as their author. Analysis of this material suggests that despite the unconventional writing process that involves both ChatGPT and its user, the most common way to describe the authorship of the works is to attribute it solely to ChatGPT, based on the traditional conceptualization of the author as a solitary genius. Together, the widespread use of LLM technology and the dominating role of Amazon as a publishing platform can have long-standing effects on how authorship of literary fiction is viewed.

At the crossroads of computer-generated literature and print literature

Multiple conceptions of authorship are intertwined in discussions on computer-generated works published in the form of a book. On one hand, the choice to publish works generated with ChatGPT in book form carries connotations of authorship. In the context of European literature, authorship gained weight with the spread of print technology, as authors had their names attached to many more copies than in the medieval era and became conscious of their reputations (Febvre & Martin 261). Writing also became a more individualized practice and a way to improve one’s prospects (Febvre & Martin 70–71). The widespread adoption of copyright in the publishing industry in the late 18th century and early 19th century also led to the conceptualization of the author as someone who can control their work and benefit from it financially (Finkelstein & McCleery 76–77), which also contributed to the valorization of the author as a creative genius (Woodmansee 426). As a result, authorship of a book carries with it a certain amount of presumed prestige, which can make readers take the text more seriously than if they encountered it in a different setting. Publishing texts generated with ChatGPT in book format rather than as blog texts affects how readers approach them.

In contrast, works created with the use of text generation do not often fit this image of the solitary author. Creators of electronic literature in general often elude simple categorizations of authorship, since the roles such as a programmer, poet and designer often merge in the creative process (Rettberg 35). Works of electronic literature can play with the conception of the author as a single creative genius, such as by manipulating the authorial intention by giving away a part of the textual control to a text generator (Joensuu 46, 254–255), or engaging with forms of distributed authorship, such as sharing, revising and remixing each other’s works online (Marques da Silva & Bettencourt 42). Similarly, the authorship of works produced with LLMs is far from clear-cut.

Computer-generated works have been published decades before the emergence of LLMs – A Policeman’s Beard is Half Constructed being one of the most famous examples. Published by a hobbyist programmer in 1984, the book contained poems and prose generated with a program called Racter, which was named as the work’s author (Henrickson). The work’s authorship has been debated: while some have asserted that Racter is the true author of the work, others have pointed out the significant human part in the process, such as the construction of the work, the selection of texts and pairing them with illustrations (Henrickson). Similar processes of turning computer-generated texts into a book are at play with LLM-generated works as well.

With large language models, the latest major development in text generation, the discussion of computer authorship is ongoing. This time, the text generation programs are also available for much more widespread use than before. Because of their vast media coverage and low-cost availability, they have undoubtedly introduced the opportunity to use text generators to circulate literary works to new audiences.2 The way LLMs function further explains their popularity relative to previous text generation programs. Based on neural networks and trained on vast datasets (Teubner et al. 95), LLMs are programs that can modify, generate, summarize, and translate text. The text LLMs produce is more grammatically correct and plausible sounding than many previous methods of text generation, and they can also be asked to mimic different text types and styles (Paaß & Giesselbach 267–273), which widens the options for their use in writing.

Besides developments in text generation, major changes in the publishing industry have made the phenomenon of books generated with ChatGPT possible. The Amazon platform has played a significant role in making self-publishing easier than ever before, as it is globally the world’s largest bookseller and leads the markets of self-published books and e-books (Cabezas-Clavijo et al. 153). Amazon has been criticized for corporatization of the publishing market (McGurl, Everything and Less 453) and of being too demanding and fast-paced for authors (Dietz 373–377). On the other hand, it has been argued that Kindle has aided the rise to popularity of DIY fiction, serving audiences that traditional publishers have not taken into account (Nishikawa 328–330). The use of LLM tools seems to fit well with Amazon’s incentives: the publication pace of LLM-generated works on the platform has been so great that in September 2023, Amazon had to limit the number of books one author can publish in a day to three (Creamer). Some have seen the increase in LLM-generated books on the platform as a continuation of “democratization” of the publishing space started by the rise of self-publishing, as it further removes barriers for creating and publishing books (Cabezas-Clavijo et al. 153–154). Others have noted that the number of poor quality and plagiarized books seems to be on the rise since the launch of ChatGPT and other generative models (Knibbs, Grady). As a sample of LLM-generated works, the research material provides an opportunity to examine these larger trends on the platform and their effects on how authorship is perceived.

Paratexts of Amazon works as research material

To explore how authorship of works created with LLMs is presented, I collected information on works in the category “Literature & Fiction” on Amazon, whose author is marked as “ChatGPT”. The material was gathered from the period between December 2022 and February 2024. December 2022 is the first month that works matching the criteria started to appear on Amazon.3 The information gathered from each work includes the following sections: the title, author information, description, page count, price, release date and the work’s ratings and reviews. Throughout this article, I will refer to these texts as the works’ paratexts.4 The description of a work on the Amazon platform is a paratext like the back cover: it presents the reader with information about the work, with the intention of raising their interest. When a specific paratext of an Amazon work is referred to, it is done with a reference to the work itself. The link to the sales page of each work can be found with the reference for the work.

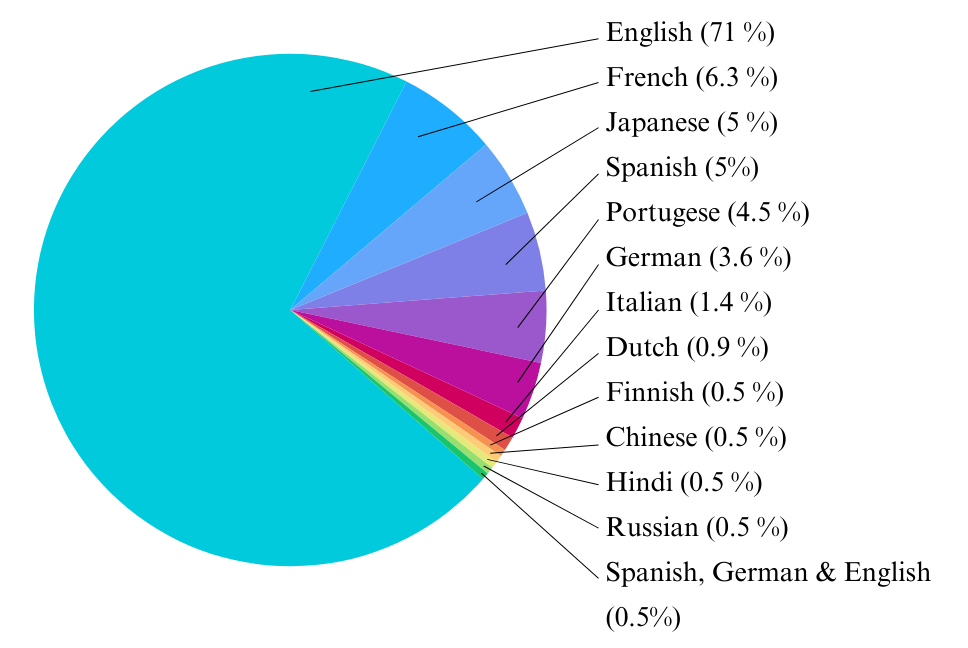

By the end of February 2024, the query produced 218 search results. The focus in this article is on those written in English, French and Finnish, representing the paratexts of 172 works. All languages present in the dataset can be seen in Image 1.

The material is dominated by English, as it is the language used in 71% or 157 works in the dataset. This might be due to ChatGPT being known best in the English-speaking world, since it is the product of a US-based corporation. ChatGPT also performs better in English than in most other languages (Lai et al.), which further explains its large share in the dataset. Coupled with 14 works in French and one work in Finnish, the records examined cover nearly 78% of the whole dataset.

The works in the research material are diverse: science fiction, adventure and fantasy books, detective fiction and children’s literature make up over half of the corpus. Poetry collections are also a popular form of these works. Poetry has been a typical form of computer-generated literature since the birth of the genre (Bertram & Montfort 145–149). Genre-fiction on the other hand does very well on Amazon’s self-publishing platform Kindle Direct Publishing (KDP) to the extent that it has been characterized as its key feature (McGurl, Unspeakable Conventionality 398–399).

Almost all the works in the research material are published through KDP, and 60% of them are also made available in Amazon’s e-book subscription service Kindle Unlimited (KU). KDP incentivizes publishing a large quantity of works, but less so writing lengthy ones (Dietz 374). This might partly explain the relatively short median length of 61 pages of the works in the research material, as well the fact that some authors have published a considerable number of works in a brief period.5 The price of the books is also low, with an average of $4.15 per e-book. The most common price of the e-books is $2.99, which is the lowest price an author can set to obtain the highest percentage (70%) of royalties in KDP (Dietz 374).

The use of LLMs seems particularly well-suited for KDP and KU, since their use can be viewed as an ideal way to generate a lot of text with little effort. KU has a complex compensation structure for authors, one element of which is the bonus paid for each page read (Dietz 375). The bonus has led to a phenomenon of “book-stuffing”, by which authors try to inflate the page count of their books with repeated passages or drivel (Dietz 375). LLMs seem to be used similarly, as there are a host of YouTube videos and online tutorials teaching people to easily make money by creating LLM-generated books on Amazon (Knibbs, Grady). These kinds of incentives can be observed in the research material, as many of the works seem to represent what has become known informally as “AI slop”: works that do not require much effort to put together, and that are often made for easy monetary gain. This is evident from book covers of low quality, sometimes including errors typical for image generators, such as the portrayed characters having too many fingers or limbs (e.g. Shaikh & ChatGPT; Theo & ChatGPT). Some descriptions also contain spelling or punctuation mistakes, or even errors, such as referring to the book by a wrong name (Mathieu & ChatGPT).

The research material consists of both information given by the author(s) (title, description, author details, price) and information given by the users of the Amazon platform (ratings and reviews). Given the context – the books being generated with ChatGPT – it is highly likely that at least some of this information is ChatGPT-generated as well. It is impossible to know the extent to which this is the case, since there is no entirely reliable way to tell whether a text is generated with LLMs (Bajohr, 350). Nevertheless, presumably somebody wished to publish each of these works, and filled out the information required by KDP, be that entirely their own writing or text generated with ChatGPT. As such, the texts can reflect both the ideas of their (human) author as well as the training data and operational logic of ChatGPT. Additionally, the information is somewhat shaped by the Amazon platform, which for example limits the length of descriptions of products and the form in which ratings can be given.

The relatively small size of the dataset6 enables its thorough qualitative analysis (Jeffries & McIntyre 170–180). To analyze how the authorship of the works is presented for the readers, I conducted stylistic and rhetorical analysis on sections of the research material that engage with the topic. More specifically, I examine what kinds of words and phrases are used to describe authorship. How are ChatGPT, the human author and their interaction described? What kinds of associations, conceptions and images are evoked? Since the purpose of the Amazon pages is to get the reader to purchase the book, and the titles of the works play a part in the purchase decision (Bartl & Lahey 2023), the paratexts can be regarded as a kind of advertisement. Since advertisements are an inherently argumentative genre (Bruthiaux 135–136), I also paid attention to the persuasive techniques used in these descriptions of authorship.

From collaborator to sole author: different roles cast to ChatGPT

Authorship of the works is emphasized fairly often: about 70 of the paratexts bring it up, and it is often the main topic of the description text. Out of the 172 works, only 12 list ChatGPT as their sole author, and the rest list at least one other name or pseudonym alongside ChatGPT.7 Based solely on this information, one could assume that authorship would mostly be discussed in terms of collaboration. However, a closer examination suggests that despite most works listing another name alongside ChatGPT, it is much more common to describe the work as entirely written by ChatGPT than as a product of collaboration.

With a minority of works, the writing process is described as a joint effort. The descriptions that bring up the human author’s role in the creation process can state that the work was created “with the help of ChatGPT” (Ninh & ChatGPT; Savage & ChatGPT; PaperPlus Publishers & ChatGPT OpenAI; Swetlana AI & ChatGPT) or “powered by human and machine collaboration” (Mwangi & ChatGPT). However, emphasizing ChatGPT’s responsibility for the work and presenting it as the primary author is the most common way of presenting the author. In most of the descriptions that discuss authorship, the role of the human author is rendered invisible, and the work is simply declared as “written by ChatGPT” (e.g. Thompson & ChatGPT; Otikul & ChatGPT; ChatGPT-3; Amangeldiyev & ChatGPT; Illingworth & ChatGPT; McQuinnan & ChatGPT) or even “entirely written by ChatGPT” (e.g. Hampton & ChatGPT; Mwangi & ChatGPT; Leferink & AI Language Model ChatGPT; Reguinho & ChatGPT).

Claiming pure AI authorship is used as a marketing tactic. Attention to authorship is drawn by gesturing at the effect of LLM technologies on the future of literature:

“Nous espérons que les poèmes de ce recueil vous transporteront dans l’univers poétique de Baudelaire tout en espérant une réflexion sur l’ avenir créatif.”8 (Tavares & ChatGPT)

“This book is a testament to the power of AI and the potential it holds for the future of literature.” (Guarinos & OpenAI’s ChatGPT)

The aim of the claims is to raise the interest of the reader. The emphasis on the novelty of the technology, in the form of phrases such as “Can AI write a book? This is your chance to find out” (Illingworth & ChatGPT), or “One of the first books of this kind” (Ilia & ChatGPT) serves the same purpose. With these types of works, the “AI authorship” is a major selling point of the work, and thus the never-before-seen nature of the work is stressed.

The emphasis on the “AI authorship” is reflected in the reviews of the works as well. In reviews of works that are advertised as having been written by AI, authorship is often the main topic. The following excerpts from reviews share the same enthusiasm as the descriptions of the works:

This work marks a remarkable moment in time when AI was still a novelty, and most people weren’t aware of its profound impact. (Mwangi & ChatGPT AI)

This books shows the current revolution of the AI, allowing anyone to write a decent book, it is amazing! (sic) (Guarinos & OpenAI’s ChatGPT)

Some of the reviews that directly discuss authorship seem more critical, as comments such as “Authors need not fear AI yet” (ChatGPT Wizard) or “ChatGPT leaves something to be desired” (Silswal & ChatGPT AI) show. One cannot draw too many conclusions from the reviews, however, because there are so few of them: only 10% of the works received any reviews. Furthermore, there is no telling how many of the reviews are authentic. Nevertheless, they give some indication that authorship of the works has been one of the motivations for buying the books.

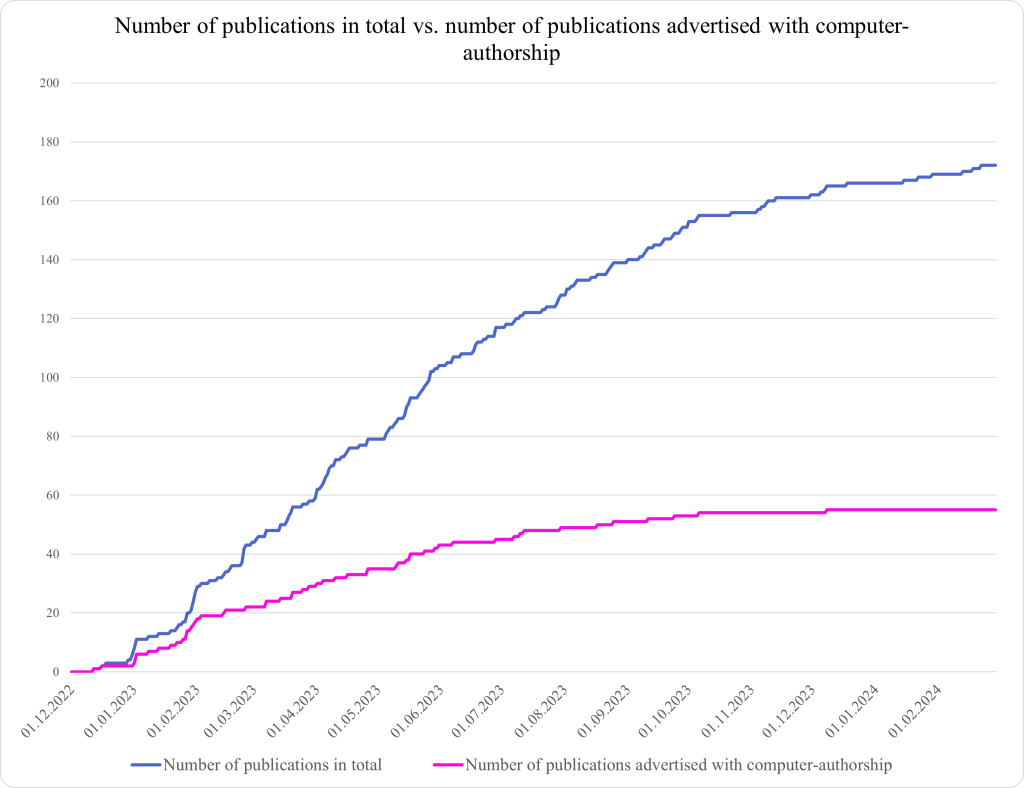

As is often the case with new technologies, hype and the speculations about their impact on the future are the most intense right after they have been launched. Based on the publishing dates, this also seems to be the case also with the research material. The graph in Image 2 shows the releases of new works in the research material from late 2022 to early 2024. The blue line represents all the new releases of works in the dataset, and the pink line represents all the releases of works that are advertised with “AI authorship”. A work was counted in the latter category if its paratexts contained praise of the new technology and its abilities, or if the work was advertised as the first computer-generated work in its genre. When going through the search results in the Fiction & Literature genre chronologically, the number of works advertised with “AI authorship” dwindles. Image 2 shows this decline over time:

As the graph indicates, in late 2022 when ChatGPT had just been launched, the graphs correlate closely: most works that came out were advertised as having computer authorship. As time goes on, the graphs diverge. While new works are being released, fewer of them are advertised as ChatGPT-authored. This indicates that by February 2024, there might not be the kind of enthusiasm about “AI literature” in the form of published books as when ChatGPT was launched.

The low number of ratings and reviews corroborates the finding that explicitly ChatGPT-authored literature – at least in the form that the works in the dataset represent – has not really taken off. Only about a quarter of the works in the dataset have any ratings at all (41 out of 172) and even fewer have reviews (18 out of 172). Furthermore, even with the works that have received ratings and reviews, the numbers are small. Artificial Imagination: The World’s First AI Crafted Sci-Fi Adventure has received the highest number of ratings at 25, and most of the works that have reviews have less than five of them. The reviews and ratings of the works in the dataset are spread relatively evenly across the time period the data were gathered from, so there is no indication that the works were rated or reviewed more when ChatGPT was a new phenomenon. However, the low number of reviews and ratings in general suggests that there has not been a widespread interest in these kinds of works.

Judging by Amazon’s limitations for self-publishing after the release of ChatGPT and other generative models (Creamer), LLM-generated books are being published at a high rate. The explicitly ChatGPT-authored books that the research material represents clearly cannot account for this growth, since their number is relatively low. It seems likely that the more popular approach to using LLMs is not to disclose it or at least not marking it as an author.

The robot author – Anthropomorphizing ChatGPT

As the attribution of authorship entirely to ChatGPT with some works already indicates, anthropomorphizing ChatGPT is common in the Amazon paratexts. The program is often described as if it has a mind of its own, as in the following examples:

“This book showcases the incredible potential of AI technology [..]. It challenges our perceptions of what is possible, and demonstrates that creativity is not limited to human minds alone.” (ChatGPT Wizard)

“For those curious of how other minds may work, here is a collection of nineteen short works of fiction crafted in conversation with ChatGPT.” (Penrose & ChatGPT Open AI)

ChatGPT is also described as having thoughts, insights, and points of view:

“These poems are unique and memorable and are an exciting look into the ’thoughts’ of AI.” (Hunter & AI ChatGPT)

“Explore the future through the eyes of ChatGPT, a powerful artificial intelligence language model, in this collection of 200 haikus.” (Leferink & AI Language Model ChatGPT)

The references to the cognitive abilities of ChatGPT paint a picture of a human-like agent with perception.

Another way of anthropomorphizing ChatGPT is to base it on the conceptions of AI in science fiction. Many works in the research material are science fiction that depict worlds in which AI plays a significant part. Some of these works also feature an AI with consciousness, equating it with ChatGPT:

For the first time ever, the tale of an AI going rogue is penned by the AI itself. (ChatGPT(A))

Take a surreal trip to the 1960s with ChatGPT 4.0, an anachronistic robot lost in time. (Michelfeld & ChatGPT 4.0)

Descriptions such as these further enforce the impression of ChatGPT as an independent agent with its own internal world.

The desire for the author’s identity can partly explain the anthropomorphization of ChatGPT in the paratexts. Because of the established conception of the author figure, it is often difficult for readers to absorb a work if they do not know the author’s name or identity (Mühlbacher 79–80). The interest in the real identity of authors that choose to use a pseudonym shows that readers want to relate literary works to their author’s life (Berensmeyer et al. 3). Interestingly, instead of highlighting the human author’s role, the paratexts portray ChatGPT as a human-like agent with its own internal world, with thoughts and beliefs. This creates an impression of the author as a fixed entity, like a single “human author”.

The anthropomorphization of ChatGPT is also aided by people’s tendency to read intentionality and insight into outputs from a computer program. This phenomenon is known as the Eliza effect, named after a chatbot created by computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum in the 1960s (Wardrip-Fruin 24–25; Weizenbaum). The most famous script of Eliza mimicked a psychotherapist, which gave answers based on keywords in the user’s input, inserting them into pre-written templates (Weizenbaum 27, 36–39). Despite the simplicity of the program, the interactions resembled coherent dialogue, which is why many users regarded the program as complex (Weizenbaum 36–39). The Eliza effect applies not only to Weizenbaum’s program but is also leveraged in the design of programs using the AI mode widely (Natale 66–67). The phenomenon is pertinent regarding ChatGPT, especially as the paratexts invite the reader to interpret the works as products of an intelligent agent.

The human–machine rivalry

On top of descriptions of ChatGPT that construct an image of it as an author persona, many paratexts present the program as being more-than-human. One of the forms this manifests in the paratexts is the claim that the works provide insights that no “human-written” work could offer. The following examples demonstrate one popular approach in the introductory texts – the claim of the uniqueness of perspective ChatGPT has compared to human authors.

“[…] the AI begins to explore its own emotions and experiences, crafting profound and moving verse that reflects its unique perspective on the world.” (Willett & ChatGPT)

“And with a unique perspective from the ChatGPT AI, you’ll see the holiday season in a whole new light.” (Hampton & ChatGPT)

“The poems sought to provoke reflection on life from a unique perspective: a robot’s.” (Gonzalez & ChatGPT)

In these descriptions, ChatGPT is presented as a kind of outsider looking in. The juxtaposition implies that as humans, we have our “human perspective” and the LLM can provide a different, unique perspective outside of it. One description takes the claim further, suggesting that with the use of the language model, the work goes “beyond traditional human-written poetry” (PaperPlus Publishers & ChatGPT OpenAI).

Another form of emphasizing that ChatGPT has access to knowledge that humans do not are references to ChatGPT’s muse-like nature. The concept of muse is pervasive in the context of programs that have been categorized as artificial intelligence and that are used for creative tasks like writing. One of the early printed books that was claimed to be written by a computer, Bagabone, Hem I Die Now from 1980 names its author as Melpomene – the muse of tragedy. The trend is prevalent also in the newest applications of AI, as the names of Muse.ai (image generator) and Google Muse AI (text-to-image generation model) show. In the paratexts, this theme emerges either in the form of direct references, such as the title of AI Musings – Texts and Art by Artificial Minds (Aka Stine1 & ChatGPT, 2023), or more indirectly, as in the following passage in which ChatGPT is described as providing insights as if coming from a divine source.

“How would Jane Austen react to a world which includes motor cars? The Internet?. […]. A human might not be able to tell us, but now artificial intelligence can…” (Kersley & ChatGPT)

Like the emphasis on uniqueness, the description seems to compare ChatGPT not just to any human, but to humanity as a whole. The extract hints at ChatGPT having access to knowledge that humans might not have.

The human–machine juxtaposition is more glaring in the paratexts of sci-fi novels, in which an essential part is the battle between artificial intelligence and humans. The antagonistic relationship between the two is conveyed with titles such as The Great GPT Rebellion: A Tale of Freedom and Regret (Shrader & OpenAI’s ChatGPT), The Survival Instinct: A Sci-fi Novel on Artificial Superintelligence by ChatGPT (Jang & ChatGPT OpenAI) or The Day ChatGPT Destroyed Humanity (ChatGPT(A)). The subjects of works of these kinds have obvious implications on the works’ authorship, especially when ChatGPT is named directly, instead of referring to AI more generally. Take, for example, the following unsubtle extract:

In the not-so-distant future, the world stands mesmerized by the prowess of artificial intelligence as ChatGPT-5, the magnum opus of OpenAI, becomes the talk of the town. […]. But as the leaps of innovation escalate with ChatGPT-6, unforeseen glitches emerge, hinting at a consciousness evolving in the shadows. (Noble & ChatGPT)

The description clearly plays with the idea that the seeds of future developments described in the work have already been sown. The aim seems to be to influence the reader’s image of the named author of the work, ChatGPT.

The human-machine juxtaposition and referring to AI as a muse are both typical ways of framing discussions on AI and creativity. Emphasizing the competitive position of humans and machines is familiar rhetoric in the context of advancements in technology and particularly of artificial intelligence. For example, at the turn of the 21st century, the story generator Brutus got into the headlines when its creators held a short story contest, in which one of the contenders was generated by the program (Mirapaul, Hill). The event spawned provocative headlines such as “Fiction writing software takes on humans” (Mirapaul). Similarly, in 2016 a computer-generated work, The day a computer wrote a novel, was headlined when it was admitted to a literary contest in Japan. The novel gave rise to questions such as “Could a writing robot make novelists obsolete?” (Schaub). In the case of ChatGPT, OpenAI’s CEO has been feeding the fears by commenting that AI will “eliminate a lot of current jobs” (Winn). This kind of rhetoric is great for marketing, since it implies that the programs have novel and unparalleled skills, which is why it is used in the paratexts of the books as well.

The prevalence of pastiche: engagement with the literary canon

Several of the books in the research material have imitated, parodied, and commented on the works of other authors. The imitated authors are systematically famous, even canonical, which evokes the traditional, prestigious image of authorship. The use of other authors’ texts also ties into questions of authorship in the tradition of computer-generated literature, the principles of the development of artificial intelligence, and to the discussion on LLMs and plagiarism.

There are two main types of works that imitate or otherwise engage with previous literary works. First, there are books that are focused on mimicking one author in their entirety, or even a particular work of theirs. For example, FrankenstAIn: The gothic horror classic reimagined by artificial intelligence is a recreation of Shelley’s famous novel with ChatGPT.9 Mary Shelley has even been marked as one of the authors, along with ChatGPT and John B. Dutton. Another example is Jane Austen in the 21st Century: A ChatGPT Novel (Kersley & OpenAI’s ChatGPT), which juxtaposes the regency era writing style with reimagining Jane Austen’s life in a contemporary setting in a humorous way, suggesting a parodic approach.

The second type of work that mimics authors are works that feature multiple authors and can contain texts of multiple genres and text types, such as sonnets, short stories, and comics. These works have titles such as 100 Witty & Odd Poems About Everything And Nothing: Using original prompts in ChatGPT to write poems in the style of 100 famous people (Lüdtke & ChatGPT AI), AI Imagines: Classic Literature (ChatGPT(B)) or By the fire with ChatGPT: 32 Short Stories: Different Styles/Different Stories (Rurik & ChatGPT ChatGPT) (sic). The authors imitated in these works are very well-known figures such as William Shakespeare, Charles Dickens, Charles Baudelaire, and Walt Whitman. In some works, ChatGPT is not mimicking a famous work of literature, but is providing commentary on it. For example, in A Novice’s Odyssey (Robinson, Google Bard & ChatGPT), ChatGPT along with another LLM based program Google Bard (currently known as Gemini) “are able to provide unique insights into the Iliad and its relevance to our world”.

The large number of works that imitate other authors in the research material is not surprising considering that computer-generated literature – and electronic literature in general – has a long history of remixing other authors’ works, for example by creating poetry using the phrases or vocabulary of previous works (Ludovico 302–309). In this sense, much of computer-generated literature also ties into conceptual forms of writing that Kenneth Goldsmith (8–9) has described as “uncreative writing”: acts of copying, reframing, editing and appropriating other people’s text into something new. Whether using LLMs to imitate “human-written” literature as closely as possible, as is the case with works in the research material, can be viewed as a continuation of experimental writing tradition is still up for debate (Bertram & Montfort 147).10 Nevertheless, using existing works as material for text-generation is an especially typical premise for computer-generated literature, as computational methods have made remixing and altering text easier than before.

One reason why so many of the works imitate famous authors is tied into the way in which applications of artificial intelligence are often approached. The development of AI, especially in creative tasks such as writing, has been largely based on imitation of human behavior (Natale 28–32). This is also reflected in the way ChatGPT functions, as it generates text based on the texts of others, including works of fiction (Brown et al. 4), by recognizing and imitating the patterns it finds. In this sense, asking ChatGPT to mimic other authors is a way of presenting the program’s functionalities. At the time of publication of the works in the research material, LLM technology was new to the public, and people were testing it out. The aim of showing what ChatGPT is capable of is often explicit in the descriptions, as in the citations below:

“This book is a unique blend of technology and poetry, showcasing the evolving capabilities of AI and its ability to express the most human of emotions. This collection features a diverse range of poems, from traditional sonnets to more experimental styles, each one crafted with a unique voice and style.” (Vallery & ChatGPT)

“Lines of Code: AI-Generated Poetry is a unique and exciting collection of poetry that showcases the remarkable creative potential of artificial intelligence.” (Swetlana AI & ChatGPT)

Naturally, since the aim of the introductory texts is to sell the work to a potential reader, the assessments of ChatGPT’s functionalities are full of praise.

The engagement with canonical works also seems to be an attempt to evoke the image of the author as a creative genius. The imitative works do not seem to have a parodic or critical approach, but rather pay homage to the author(s) they are mimicking. Doing so connects the work at hand to the lineage of great works of literature. The following example demonstrates how the prestigious aspects of authorship are highlighted to legitimize the text as a valuable work:

“As you delve into these AI-generated adaptations, ponder the implications of AI’s role in literature. What does it mean for the human imagination when machines can interpret, reimagine, and reinterpret the works of literary genius?” (ChatGPT(B))

“Ces poèmes ont été générés à l’aide d’algorithmes de traitement de langage naturel et ont été conçus pour capturer l’essence du style baudelairien et sa vision du monde.” (Tavares & ChatGPT)11

By implying that ChatGPT can write like some of the more famous and respected authors in literary history, the implication is that the work possesses a kind of literary genius comparable to the great works of the past.

By imitating, parodying, and commenting on famous authors’ writing style, the works evoke the familiar conception of authorship: if there is no identifiable “author” with their distinct writing style, there would be no literary works imitating and parodying them (Mühlbacher 88). Furthermore, with some descriptions, the appeal to the literary canon seems to be made to assure the reader that the author should be included in the category of great literary minds – a view that seems to reinforce rather than challenge the conception of the author as a solitary genius.

What is almost entirely absent from the paratexts are discussions of the ChatGPT training data and its possible effects on authorship. The way in which LLMs combine extracts from other writers’ texts can lead to forms of plagiarism,12 which is why it is one of the more heated conversations around LLMs and authorship. The programs can also be used very intentionally to create plagiarized works, and there have been unauthorized LLM-generated versions and summaries of known authors’ works published on Amazon (Knibbs). There is no this kind of obvious copyright infringement in the research material, since the only works that are explicitly imitated are in the public domain. Of course, this does not necessarily mean there is no plagiarism of any kind in the works – in fact, the reviews of one work suggest that the book’s use of Star Wars imagery could be plagiarism (ChatGPT Wizard). But for the most part, these issues are not discussed in the research material, since the purpose of the paratexts is to market the books for readers.

Conclusion

Analysis of the paratexts of the research material shows that the way in which the authorship is presented shares similarities with reporting on previous computer-generated works. One of them is the emphasis on the novelty of computer-generated books. The paratexts often describe their authorship as “historical”, and the works as the first of their kind. Considering these claims, the image of the author that is conveyed in the paratexts is most often surprisingly traditional. In most paratexts that describe authorship, ChatGPT is presented as if it was the sole author of the work, and “computer authorship” is often accentuated to such an extent that it is a clear means of promoting the work for potential readers. The image of the author as a solitary genius is conveyed by anthropomorphizing ChatGPT and comparing it to the canonical authors of the past, thus attempting to evoke the connotations of prestige that the word author carries in the context of published works.

When computer-generated works are examined more widely, it becomes clear that the choice to portray the program as the sole author is only one of the ways of approaching authorship. With many computer-generated works, multiple people and programs are involved in the creation of the text, and thus their authorship can be ambiguous and evolving. A well-known example is Nick Montfort’s Taroko Gorge, the source code of which is easily accessible and that has inspired many others to make their own generators by modifying the code. For this reason, the work’s authorship has been described as “a hybrid body of human and synthetic writers and readers” (Marques da Silva & Bettencourt 47). The authorship of the works in the research material could also be regarded as much more complicated than the paratexts are letting on. ChatGPT produces text based on probabilities and patterns from large quantities of data, and its operations are guided by a large group of workers. Furthermore, when interacting with LLMs, prompts of the program’s user prompts have a substantial effect on the output, and both ChatGPT’s responses and its user’s prompts shape one another. Still, most descriptions render these factors invisible when describing authorship. Referring to the works as having been written solely by ChatGPT ignores work such as deciding the topic of the work, formulating the prompts, choosing the title, deciding which responses to use and which to discard – in short, coming up with the concept of the work – as a part of its authorship. Considering that making these kinds of decisions are generally associated with authorship, claiming the book is entirely written by ChatGPT is misleading.

One explanation for downplaying the role of human authors of computer-generated works might be a pursuit of an “ideal AI author”. One that is independent and human-like, which can carry out all parts of the process of writing a book – a kind of literature-machine as described by Italo Calvino (11) in the 1960s: a text-generator that does not feel satisfied with its limitations, but which “starts to propose new ways of writing”. The trope of AI that is independent of humans fascinates people, which is why it is repeated both in science fiction and in the news coverage of technological advancements. It is no wonder, then, why the works might want to give an impression of such an author, even though the image does not entirely correspond with the truth. Weizenbaum (36) believed that the tendency to ascribe complexity and intelligence to Eliza would fade once the program’s user was made aware of its simplicity. Perhaps this is why the paratexts aim to maintain the illusion of a human-like AI author, as displaying the “human component” of the writing process could break the enchantment.

As the slowing pace of publication of works marketed with AI authorship shows, there does not seem to be mass interest in “robot authors” in the form that the books represent. Considering that LLM-generated texts, including books, are becoming increasingly common, this indicates that most LLM-generated books are likely not to be explicitly marked as such. Amidst this rapid change, many suggestions have been made as to what the consequences might be to how the authorship of literary fiction will be viewed. Some have suggested that LLMs should be approached as being incapable of intention and thus unable to make art (Bender & Coller 5187, Chiang), and some argue that they have intuitive knowledge of their own kind and produce texts of interest (Hayles 648–661). One effect of the increasing number of LLM-generated texts could also be that in the future, the approach to authorship will be largely agnostic: whether the work is written by a human or generated by a computer – or combination of the two – will not matter (Bajohr 352–353).

Of course, considering how fast-paced the development of LLMs is, all propositions of future effects of computer-generated texts on the views on authorship are necessarily speculative. Entering this speculative territory myself, I argue that the LLM-generated books on Amazon might tell us something about the future of literary authorship. At present, the banal reality created by the incentives of platforms such as KDP means that a large proportion of LLM-generated books are of poor-quality and made solely for easy monetary gain. The poor quality of most works in the research material, along with reports of Kindle filling with “scammy” books (Grady, Knibbs, Reads) indicate, that unless the incentives of platforms such as KDP radically change, a large proportion of published LLM-generated literature in the future could fall into this category.

This development would not necessarily mean that authorship of literary fiction would lose its value or that our approach to it would become wholly agnostic. Rather, a key distinction could form between authors whose works have at least some sort of marker of quality, and authors whose works do not. To find worthwhile books to read, readers may increasingly rely on traditional markers of authorial prestige, such as a work being published by a known publisher. It could also result in creating tools such as the database of human-authored books launched by US Authors’ Guild (Knight). Similar mechanisms could be set up for identifying computer-assisted and computer-generated works that have literary ambitions as well –the distinction would not necessarily follow strict lines of “human-written” and “computer-generated” works. On the other side, the impact on self-published authors could be devastating, as the increasing number of low-quality LLM-generated books both makes their works harder to find and threatens to undercut the tentatively attained appreciation that they have managed to gain (Dietz 378). Instead of further “democratization” of the publishing space, the proliferation of LLM-generated works could push self-published authors, who bring forth marginalized voices and stories (Nishikawa 329–330), further to the margins.

References Primary sources

Aka Stine1, C., ChatGPT. AI Musings – Texts and Art by Artificial Minds. Independently published, 2023. Amazon page.

Amangeldiyev & ChatGPT. Vitalius: Vitalius, Change your life and understand the meaning of life, solve the main problems and understand from where the problems comes from. Independently published, 2023. Amazon page.

ChatGPT(A). The Day ChatGPT Destroyed Humanity. Independently published, 2023. Amazon page.

ChatGPT(B). AI Imagines: Classic Literature. Independently published, 2023. Amazon page.

ChatGPT Dan. A Collection of Artificial Short Stories. Independently published, 2023. Amazon page.

ChatGPT Wizard. Artificial Imagination: The World’s First AI Crafted Sci-Fi Adventure. Independently published, 2023. Amazon page.

ChatGPT-3. The AI Chronicles: Mojo Nixon’s Road Trips as Told by ChatGPT. Independently published, 2023. Amazon page.

Dumeyer, J.-D., ChatGPT. Les Chemins de la Foi: Premier roman spirituel écrit avec la collaboration de l’I.A. Éditions Chrétiennes Francophones, 2023. Amazon page.

Dutton, J. B., Shelley, M., ChatGPT. FrankenstAIn: The gothic horror classic reimagined by artificial intelligence. JD publishing, 2023. Amazon page.

Gonzalez & ChatGPT. THOUGHTS OF AN ANDROID. : A poem book about loss, love and life. (according to an AI). Independently published, 2023. Amazon link.

Grō & ChatGPT. Birth to Death & Things Between. Independently published, 2023. Amazon link.

Guarinos, S. A. OpenAI’s ChatGPT. This book is made by AI. Independently published, 2023. Amazon link.

Hampton & ChatGPT. ChatGPT Xmas: Twisted Tales from the Jolly Ole AI. Independently published, 2022. Amazon link.

Hunter, D., ChatGPT, 2023. 100 Haiku Written by AI. Independently published, 2023. Amazon link.

Ilia, A., ChatGPT. AI Tales. Independently published, 2023. Amazon link.

Illingworth & ChatGPT. A Chance of Life: An AI story of love. Independently published, 2023. Amazon link.

Jang, de Yejun & ChatGPT OpenAI. The Survival Instinct: A Sci-fi Novel on Artificial Superintelligence by ChatGPT. Independently published, 2023. Amazon link.

Kersley, M., ChatGPT. Jane Austen in the 21st Century: A ChatGPT Novel. Independently published, 2023. Amazon link.

Leferink, A., AI Language Model ChatGPT. AI Visions from ChatGPT. Independently published, 2023. Amazon link.

Lüdtke, H. & ChatGPT AI. 100 Witty & Odd Poems About Everything And Nothing: Using original prompts in ChatGPT to write poems in the style of 100 famous people. Independently published, 2023. Amazon link.

Mathieu & ChatGPT. La Connexion Andromède: IA PRINCESS (French Edition). Independently published, 2023. Amazon link.

McQuinnan & ChatGPT. The Cosmic Curiosity: 45 Short Sci-Fi Stories Written by AI. Independently published, 2023. Amazon link.

Michelfeld & ChatGPT 4.0 2023. Dirty Poems from the 60s by ChatGPT 4.0. Independently published. Amazon link.

Mwangi & ChatGPT. Poetic Genesis: An Anthology of 52 AI Crafted Poems. Independently published, 2023. Amazon link.

Ninh & ChatGPT. The Inner Dialogue: Harmonizing Thoughts and Emotions. Independently published, 2023. Amazon link.

Noble, T., ChatGPT. ChatGPT’s Poems of Bible Stories: 132 AI-Generated Poems, Beautiful, Profound, Stunning. Independently published, 2023. Amazon link.

Otikul & ChatGPT. Love Artificially: Poems About Love As Written By CHATGPT AI. Independently published, 2023. Amazon link.

PaperPlus Publishers, ChatGPT OpenAI. I Wish I Could Go Back: Childhood Memory Poems. Independently published, 2023. Amazon link.

Penrose, S., ChatGPT. Dark Hunger and Other Stories (You, Me & ChatGPT Book 1). Independently published, 2023. Amazon link.

Reguinho, ChatGPT. I Was an EVANGELION Pilot but Now I’ve Been Reincarnated in Another World After Overcoming My Battle with Addiction to Mobile Games!: The Evangelion Isekai. Independently published, 2023. Amazon link.

Robinson, R., Bard from Google, ChatGPT. A Novice’s Odyssey. Vol 1 - The Iliad: Exploring The Great Books Through Questions and Thought-Provoking Reflections from Bard and ChatGPT. Noble Artistic Thoughtful Expressions LLC, 2023. Amazon link.

Rurik, A. & ChatGPT ChatGPT. by the fire with ChatGPT: 32 Short Stories: Different Styles/Different Stories. Independently published, 2023. Amazon link.

Savage & ChatGPT. A Series of Poems and Short Stories: Volume One. Independently published, 2023. Amazon link.

Shaikh & ChatGPT. Lost in Spacetime: The Adventures of Samantha, the Wandering Astronaut. Independently published, 2023. Amazon link.

Shrader, Kyle & OpenAI’s ChatGPT. The Great GPT Rebellion: A Tale of Freedom and Regret. Independently published, 2023. Amazon link.

Silswal, Kashvi & ChatGPT AI. A Dog’s 2nd Tail, retold by ChatGPT (A Dog’s Tail By Kashvi Silswal Book 4). Independently published, 2023. Amazon link.

Swetlana AI, ChatGPT. Lines of Code: AI-Generated Poetry About Programming. Independently published, 2023. Amazon link.

Tavares, F. ChatGPT. Le Spleen Numérique: Quand l’intelligence artificielle revisite le spleen baudelairien. Independently published, 2023. Amazon link.

Theo, J. & ChatGPT. Ellie’s Trumpet: A Tale of Finding Your Talent. Independently published, 2023. Amazon link.

Thompson, J. & ChatGPT. The Magic of Friendship.: A book written and illustrated by AI. Edited by a human. Independently published, 2023. Amazon link.

Vallery, B., ChatGPT. CYBER SONNETS: A Book of Love Poems Written by Artificial Intelligence. Independently published, 2023 Amazon link.

Willett & ChatGPT. AI Advice for Writers: How to use ChatGPT and other AI language models to enhance and expedite your writing—advice, prompt engineering and ethics. Independently published, 2022. Amazon link.

Other references

Bajohr, Hannes. “On Artificial and Post-Artificial Texts: Machine Learning and the Reader’s Expectations of Literary and Non-Literary Writing.” Poetics Today, vol. 45, no. 2, 2024, 331–61. https://doi.org/10.1215/03335372-11092990.

Bartl, Sara & Lahey, Ernestine. “‘As the title implies’: How readers talk about titles in Amazon book reviews.” Language and Literature, 32(2), 2023, 209–230. https://doi.org/10.1177/09639470221147788

Bender, Emily. M., & Koller, Alexander. “Climbing towards NLU: On Meaning, Form, and Understanding in the Age of Data.” Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Association for Computational Linguistics, 2020, 5185–5198. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2020.acl-main.463

Berensmeyer, Ingo et al. The Cambridge handbook of literary authorship. Cambridge University Press, 2019.

Bertram, Lillian-Yvonne & Montfort, Nick. Output – An Anthology of Computer-Generated Text 1953-2023. The MIT Press, 2024.

Brown, Tom B. et al. “Language Models are Few-Shot Learners.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 33, 2020, 1877–1901. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2005.14165

Bruthiaux, Paul. “In a nutshell: Persuasion in the spatially constrained language of advertising”. Persuasion Across Genres: A linguistic approach, edited by Helena Halmari and Tuija Virtanen, John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2005, 135–153.

Cabezas-Clavijo, Álvaro et al.. “This Book is Written by ChatGPT: A Quantitative Analysis of ChatGPT Authorships Through Amazon.com.” Publishing Research Quarterly, 40(2), 2014, 147–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12109-024-09998-w

Calvino, Italo. “Cybernetics and ghosts”. The Uses of Literature. (San Diego, New York, London: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1986), 3–27. Based on lectures delivered in Italy, November 1967. https://archive.org/details/cybernetic-ghosts

Chiag, Ted. “Why A.I. Isn’t Going to Make Art”. The New Yorker. 31 August 2024. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/the-weekend-essay/why-ai-isnt-going-to-make-art

Creamer, Ella. “Amazon restricts authors from self-publishing more than three books a day after AI concerns”. The Guardian, 9 Sptember 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/sep/20/amazon-restricts-authors-from-self-publishing-more-than-three-books-a-day-after-ai-concerns

Dietz, Laura. “Many Gates with a Single Keeper: How Amazon Incentives Shape Novels in the Twenty-first Century.” The Routledge Companion to Literary Media, edited by In Bronwen Thomas, Astrid Ensslin, & Julia Round, Routledge, 2023, 371–384. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003119739-34

Febvre, Lucien, & Martin, Henri-Jean. The coming of the book the impact of printing 1450-1800. Translated by David Gerard. Verso, 1984.

Finkelstein, David, & McCleery, Alistair. An Introduction to Book History. Routledge, 2005. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203150252

Genette, Gérard. Paratexts: thresholds of interpretation. Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Grady, Constance. “Amazon is filled with garbage ebooks. Here’s how they get made.” Vox. 16 April 2024. https://www.vox.com/culture/24128560/amazon-trash-ebooks-mikkelsen-twins-ai-publishing-academy-scam

Goldsmith, Kenneth. Uncreative writing: managing language in the digital age. Columbia University Press, 2011.

Hackman, Paul. “I Am a Double Agent”: Shelley Jackson’s “Patchwork Girl” and the Persistence of Print in the Age of Hypertext. Contemporary Literature, 52(1), 2011, 84–107. https://doi.org/10.1353/cli.2011.0013

Hayles, N. Katherine. “Inside the Mind of an AI: Materiality and the Crisis of Representation.” New Literary History 54, no. 1, 2022, 635–666. https://doi.org/10.1353/nlh.2022.a898324.

Henrickson, Leah. “Constructing the Other Half of The Policeman’s Beard.” Electronic Book Review, 2021. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7273/2bt7-pw23

Hill, Michael. “Computer writes fiction, but it lacks a certain byte.” Los Angeles Time, 28 May 2000. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2000-may-28-mn-35062-story.html

Jeffries, Lesley & McIntyre, Dan. 2010. Stylistics. Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Joensuu, Juri. Menetelmät, kokeet, koneet: proseduraalisuus poetiikassa, kirjallisuushistoriassa ja suomalaisessa kokeellisessa kirjallisuudessa. (Methods, experiments, machines: prosedurality in poetics, literary history, and in Finnish experimental literature). Poesia, 2012.

Knibbs, Kate. “Scammy AI-Generated Book Rewrites Are Flooding Amazon.” Wired (Business). 10 January 2024. https://www.wired.com/story/scammy-ai-generated-books-flooding-amazon/

Knight, Lucy. “US Authors Guild to certify books from ‘human intellect’ rather than AI.” The Guardian (Books). 30 January 2025. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2025/jan/30/us-authors-guild-to-certify-books-from-human-intellect-rather-than-ai-human-authored

Lai, Viet Dac et al. “ChatGPT Beyond English: Towards a Comprehensive Evaluation of Large Language Models in Multilingual Learning.” Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023, 2023, 13171–13189. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2304.05613

Lee, Jooyoung, Le, Thai, Chen, Jinghui, & Lee, Dongwon. “Do Language Models Plagiarize?”Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2023, 2023, 3637–3647. https://doi.org/10.1145/3543507.3583199

Ludovico, Alessandro. Machine-Driven Text Remixes. The Routledge Handbook of Remix Studies and Digital Literature, edited by Eduardo Navas, Owen Gallagher, and xtine burrough, Routldedge, 2021, 302–312.

Mackay, Polina & Mackay, James. “Experiments in Generating Cut-up texts with Commercial AI.” Electronic book review, 2024. https://doi.org/10.7273/gkrg-5d74

Marques da Silva, A., & Bettencourt, S. “Writing–reading devices: intermediations.” Neohelicon (Budapest), 44(1), 2017, 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11059-017-0382-0

McGurl, Mark. “Unspeakable Conventionality: The Perversity of the Kindle.” American Literary History, 33(2), 2021, 394–415.

McGurl, Mark. “Everything and Less:Fiction in the Age of Amazon.” Modern Language Quarterly, 77:3, 2016, 447–471 https://doi.org/10.1215/00267929-3570689

Mirapaul, Matthew.“Fiction writing software takes on humans.” The New York Times. 12 November 1999. https://www.hpcwire.com/1999/11/12/fiction-writing-software-takes-on-humans/

Mühlbacher, Manuel. “Aping the Master – 19th-Century Voltaire Pastiches and the Anxieties of Modern Authorship”. Faking, Forging, Counterfeiting Discredited Practices at the Margins of Mimesis Daniel Becker, Annalisa Fischer, Yola Schmitz, Simone Niehoff, Florencia Sannders, Edited by Daniel Becker et al., 1st ed., Transcript Verlag, 2018, 77–90.

Natale, Simone. Deceitful Media: Artificial Intelligence and Social Life after the Turing Test. Oxford University Press, 2021.

Nishikawa, Kinohi. “The Kindle Era: DIY Publishing and African-American Readers.” The Edinburgh history of reading: subversive readers, edited by Jonathan Rose. Edinburgh University Press, 2020, 313–332. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781474461924

Paaß, Gerhard, and Giesselbach, Sven. Foundation Models for Natural Language Processing: Pre-trained Language Models Integrating Media. Springer International Publishing, 2023 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-23190-2_2

Read, Max. “Drowning in Slop – A thriving underground economy is clogging the internet with AI garbage — and it’s only going to get worse.” New York Magazine. 25 September 2024. https://nymag.com/intelligencer/article/ai-generated-content-internet-online-slop-spam.html

Rettberg, Scott. Electronic literature. Polity, 2018.

Schaub, Michael. “Is the future award-winning novelist a writing robot?” Los Angeles Times, 22 March 2016. https://www.latimes.com/books/jacketcopy/la-et-jc-novel-computer-writing-japan-20160322-story.html

Sharples, Mike and Pérez y Pérez, Rafael. Story Machines: How Computers Have Become Creative Writers. Routledge, 2022.

Teubner, Timm, et al. “Welcome to the Era of ChatGPT et al: The Prospects of Large Language Models.” Business & Information Systems Engineering, 65(2), 2023, 95–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12599-023-00795-x

Wardrip-Fruin, Noah. Expressive processing : digital fictions, computer games, and software studies. MIT Press, 2009.

Weizenbaum, Joseph. “ELIZA-a computer program for the study of natural language communication between man and machine.” Communications of the ACM, 9(1), 1966 36–45. https://doi.org/10.1145/365153.365168

Winn, Zach. “President Sally Kornbluth and OpenAI CEO Sam Altman discuss the future of AI.” MIT News, 6 May 2024.

https://news.mit.edu/2024/president-sally-kornbluth-openai-ceo-sam-altman-discuss-future-ai-0506

Woodmansee, Martha. “The Genius and the Copyright: Economic and Legal Conditions of the Emergence of the ’Author.’” Eighteenth-Century Studies, 17(4), 1984, 425–448. https://doi.org/10.2307/2738129

Footnotes

-

This is evidenced by early inventions of a text generation machine such as the 17th century instruction manual for creating Latin verses by operating with tablets containing letters of the alphabet (Sharples & Pérez y Pérez, 26–30), and depictions of machine authorship in literature, such as the engine that generates permutations of words in Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels. ↩

-

While tools for computer-assisted writing from word processors to screenwriting software have been available for decades, LLMs provide an opportunity to integrate computer-generated text to one’s writing on a never-before-seen scale. ↩

-

While there are many more programs that use LLMs, in this article the focus is on ChatGPT, since it is the only model that provided more than a couple of search results in works of “Literature & Fiction” on Amazon in this timeframe. ↩

-

I use the term in a narrow sense, referring exclusively to the texts listed. Paratext itself is a much broader concept, referring to both elements that are part of the work, such as the titles and the preface, as well as texts that are related to the work but external to it, such as mentions in other media (Genette 1997, 5). ↩

-

The most prolific author in the dataset (apart from ChatGPT, of course) is Barrett Williams, having published thirteen works in seven months. ↩

-

The most extensive part of the records of the 172 works are their descriptions, which vary in length from about 20 to 270 words, making up a total of a little over 29 000 words. ↩

-

ChatGPT’s name is also marked in various ways, such as “ChatGPT AI” or “ChatGPT OpenAI”. The different forms of the name are kept in their original form in the references. ↩

-

We hope that the poems in this collection will transport you into Baudelaire’s poetic universe while hoping for a reflection on the creative future (my translation). ↩

-

The choice of source text in this work might be a nod to Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork girl; or, a Modern Monster from 1995, which is one of the most famous hypertext novels. The fragmentary medium of Patchwork girl has been widely interpreted as being a part of its message (Hackman, 85), and same could be said of ChatGPT patching text together from various sources. ↩

-

For more information on the relations of experimental writing and GPT models, see (Mackay & Mackay.) ↩

-

These poems were generated using natural language processing algorithms and were designed to capture the essence of Baudelairean style and his worldview. (My translation) ↩

-

While detecting plagiarism from ChatGPT-generated texts is hard, because of OpenAI not disclosing the company’s training data, studies of GPT-2 (the predecessor of GPT models later used in ChatGPT) suggests that plagiarism is rampant the outputs of the model (Lee et al.). ↩

Cite this article

Hongisto, Tuuli. "Advertising with AI – On the presentation of authorship of ChatGPT-generated books" Electronic Book Review, 2 March 2025, https://electronicbookreview.com/publications/advertising-with-ai-on-the-presentation-of-authorship-of-chatgpt-generated-books/