Ecocritique between Landscape and Data: The Environmental Audiotour

This article discusses the Environmental Audiotour—a work by Parikka, Patelli, and Wong through which art and technology intersect with environmental issues at the Helsinki Biennial 2023. The artist-researchers explore topics like rising sea levels affecting islands, how humans impact the environment, and ways to visualize environmental data. Overall, the authors use creative methods to understand and address environmental problems in today's digital world.

Thank you to the ELO 2023 conference, especially to its organizers, Daniela Maduro, Manuel Portela, Rui Torres, and Alex Saum-Pascual, who first hosted Professor Jussi Parikka as a keynote speaker at their conference in Coimbra, Portugal. This resulting publication is a collaboration with ELO 2023 and will also appear in their forthcoming conference publications.

What kind of ecocritique emerges from reading and writing with landscapes, cityscapes, and their environmental entanglement with art methods? This article articulates one approach to storytelling with data and urban landscapes as we respond to some of the key debates in recent critical data studies and the broader context of electronic literature about the situatedness of digital infrastructures. This manner of ecocritique works with modes of sensing and data that come to feature questions of materiality as their central element. The article focuses on our recently released Environmental Audiotour, commissioned as part of Helsinki Biennial 2023, as an example of current artistic and curatorial practices expanding the repertoire of ecocriticism (see e.g. Cohen and Duckert; Cubitt; Fan; Carter, “Electronic Literature in the Anthropocene”). This research article features three selected episodes from the Audiotour and a short version of a film informed by the tour itself, Saaret. Both were produced as part of the Critical Environmental Data project in Helsinki. We do not focus on specific passages or sections of the Audiotour in detail as our aim is not to do a close-reading of the work itself. Instead, we explicate the context of production of the project in order to build an argument about the expanded notions of environmental sensing and data that come to the fore in the curatorial context and its links to digital poetics too.

The first episode starts at the ferry stop by the sea, on the route that takes to Vallisaari island. Elemental media of water, heat, and air are central. The second episode takes place at the ruins of an abandoned weather station on the island. The imaginary of the island and mapping become some of the key threads. The third episode takes place at Hietalahti area, focusing on land reclamation. The fourth one is titled “Palm House”, after the key building of the Kaisaniemi Botanic Garden, focusing on questions of care and architectures for human and non-human life. The fifth one is situated just outside the Botanical Museum (Finnish Museum of Natural History) as it takes place in the Lichen Garden; here, questions of sensing and classification become central narrative threads. The final episode, Hanasaari, narrates a decommissioned power plant from the point of view of coal, both as a landscape feature and as logistics of natural elements: it features the travels of coal across the world and the “ghostwriting” of the city through its particulate presence. Its traces are framed and aggregated in our writing too. The audiotour was made available both in Finnish and English, but we refer only to the English voiceover in this article.

https://soundcloud.com/helsinki-biennial-2023/ced-the-environmental-1?in=helsinki-biennial-2023/sets/helsinki-biennial-2023-critical-environmental-data-the-environmental-audiotour&utm\_source=clipboard&utm\_medium=text&utm\_campaign=social\_sharing Excerpt 1 The Lichen Garden

To feature lichens in an artistic narrative about data and digital poetics seems at first peculiar. However, it works as an apt entry point into our research and practice angle. Lichens are addressed in the story as site-specific sensorial surfaces that grow and recede upon rocks. Part of the so-called Lichen Garden, they are located next to the University of Helsinki’s botanic collections, which contain a unique historical archive of these symbiotic organisms. Lichens were recognized as air sensors in early biological research, as the Finnish researcher Wilhelm Nylander discovered in his studies in the late 19th century. Some of the samples that he collected are still part of the historical collections. As organisms that have troubled the organized logistics of knowledge – of classifications and actual placement in both data tables and physical archives – they provide an interesting case for understanding biosensing in the longer history of technogeographies of data (Gabrys) before digital culture. Urban air had been perceived as an issue and thus an entity of interest and research throughout much of the 19th century in larger industrialized cities. This then also fed into a re-reading of environmental bioindicators, such as plants but also later lichen, as part of a historical periodization. As such, we follow the idea that patterns of sensing are not only indicative, but also (in)formative of their environments; in other words, sensing emerges as an active way of not just registering traces but forming such landscapes. They are not just measurement devices, but living material entities, inscriptions in these environments. Environmental sensing is, therefore, also a re-making of the environment itself, a form of becoming-with.

As a site-specific example, The Lichen Garden episode helps to introduce the key aims of this text as we connect numbers and stories, digital cultures and material landscapes into a narrative about architectures, human and non-human organisms as sentinels, as well as sites from cities to islands. Our research group was invited by Joasia Krysa, the main curator of the Helsinki Biennial 2023, as one of the curatorial intelligences involved in the conceptualization of the program, which took place from 11 June to 17 September 2023. As her expertise in algorithmic culture informed the approach to environmental issues, we responded to the key guiding terms – or prompts – of Contamination, Agency, and Regeneration and were commissioned to design the six-episode Environmental Audiotour as an alternative way to see and narrate the city of Helsinki. Besides the curatorial work, we collaborated with local partners such as the University of Arts Helsinki on questions of environmental sensing, art-methods, as well as thematic topics such as contamination. Much of this collaboration was driven by the students on the course Environment, Data, and Contamination (2022-2023). Hence, we also situated the multiple elements of our work in the context of ecomedia literacy (López) with the specific aim not just to produce curatorially and artistically significant outputs but conceptual and aesthetic instruments for students and the broader public to engage with infrastructures of sensing and meaning-making. In other words, we respond to the call in ecocriticism to interconnect scholarship and public citizenship – in this case broader audiences across public space in Helsinki (O’Dair, 150, referring to Buell, The Future of Environmental Criticism). 1

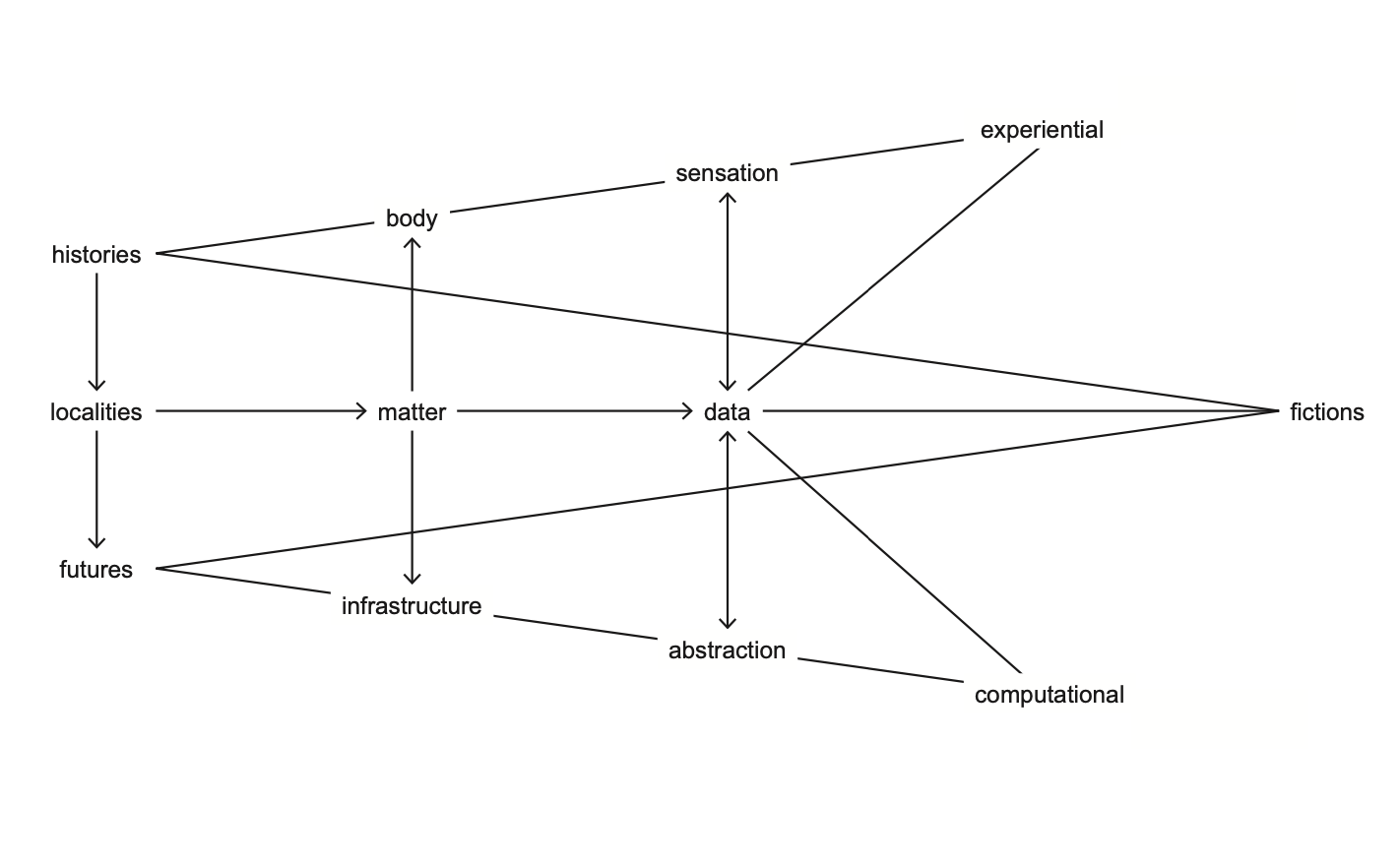

The work presented in this article resonates closely with recent themes in ecocritique. While we make this contextualization a core part of the writing in this article, it is clear that our piece as such is not electronic literature in the sense that it would be primarily executed via online or networked media. As a low-tech approach to digital culture, the episodes are available on the Soundcloud online platform; during the Biennial they were site-specifically marked and accessible with a QR-code. However, there is a significant link to shared concerns with recent electronic literature in its different material manifestations, such as J.R. Carpenter’s The Gathering Cloud (2017), An Ocean of Static (2018), and The Pleasure of the Coast (2023); Richard Carter’s projects such as Waveform (2018, 2023) and the recent Line of Flight (2023); and Shelley Jackson’s Snow (2014-), as different versions of post-digital (Berry and Dieter) readings of landscapes through contemporary and historical data. As a curatorial framing of the ecological thresholds of a cityscape, we were specifically interested in the expansion of notions of digital media as elemental media (Peters; Parikka, A Geology of Media; Fan; Starosielski) and – with respect to the context in critical data studies – data as an assemblage (Kitchin and Laurialt) of wider cultural techniques of sensing, aggregation – and site-specificity. These helped to also outline techniques of knowledge beyond enumeration as they come to address infrastructures of data and the materiality of the digital (Offenhuber). Here the move from electronic literature on network platforms to the sites and infrastructures through which data, sensing, and inscription are expanded to elemental media becomes core to our argument. To execute this idea, our stories shift between outdoor sites, such as the ruins of an old weather station, to indoor artificial climates like botanic gardens, and on to the disappearing coal landing sites of a city. As part of the curatorial brief, we also composed this into an experimental diagram (Figure 1) that acted as our “navigational design tool” to move between thematic, material, spatial, and conceptual axes.

As expressed in this article and the above diagram, our aim in the Audiotour is to layer and historicize contemporary cultures of ecological knowledge with both factual and fictional histories and speculative futures. Hence, this research article is also a contribution to the discussion on how digital cultures respond to the ecological transition. Here, our explication of the audiotour hopes to generate further dialogues by connecting works in electronic literature with those in contemporary art in terms of spatial tropes, material surfaces, and their relation to broader ways of understanding data materiality through environmental storytelling.

The next section of this text contextualizes the work in recent discussions and other artistic works in electronic literature before engaging in more detail with some of the spatial questions of our methodology and narrative.

Digital Ecofiction and Material Poetics

As part of the dialogue between the Audiotour and the international fields of electronic literature, digital arts and critical theory, we follow a few connecting threads. In the recent years, questions of ecology have become increasingly central both as thematic cues and as ways to expand notions of digitality to material manifestations of mediation. The field of Anthropocene studies intersects with digital poetics too, with many non-human forces of expression, also tied with questions of biodiversity and climate change, coming to the fore. In other words, several examples of artistic and critical reflective pieces acknowledge their own conditions of existence in the period of intensive ecological transformations. The creative methods have enabled new transdisciplinary encounters to emerge. As Rita Raley argues, practices of digital poetics have expanded to a multitude of materials and agencies outside the binary of humans and machines. In a close reading of some works from early 2000s, Raley points to David Jhave Johnston’s Sooth (2005) as well as to creative practices by Alison Clifford, Cyrille Henry, and Oni Buchanan. Raley’s argument about the expanded media ecology shifts from more traditional references such as Marshall McLuhan to the broader ecological context – and elemental media – that include questions of energy, vegetal surfaces, plants, and more. Or as Raley writes, summarizing the overview of such works in two points – firstly, “an embedding of humans and computational media within a larger assemblage comprised of human and nonhuman actors and lively, vibrant, animate matter”, and secondly “a turn from a mode of composition in which different media elements – such as text, image, video, sound, and algorithm – are contiguous but distinct to a mode of composition in which they are more clearly syncretized” (889).

The remediation of the multitude of (data) inscription surfaces – water, ice, snow, leaves, soil – is informed by work with programmable screen environments. This motif of media ecologies that combines digital and natural comes to the fore as part of the expanded materialities of digital poetics and ecocritique. Lai-Tze Fan’s analysis of recent years of digital ecofiction emphasizes the mutually co-determining relations of materiality and media, and a variety of overlapping themes of humans, nonhumans, time and history (Fan, 345-351). Fan’s analysis runs from Roderick Coover and Scott Rettberg’s Toxi•City (2014) to Shelley Jackson’s Snow (2014-) and J.R. Carpenter’s work alongside other examples while developing an argument that closely resonates with the polyphonous nature of the ecological and digital assemblage. Multiple temporalities intertwine and the processual nature of digital poetics comes to feature in parallel to, or even intimately connect with, natural processes. Hence, such works define a way of engaging with “climate change that taps into nature’s autopoiesis – nature’s ability to reproduce and maintain itself – and renders nature capable of testifying to its own trauma in a temporal rhythm that differs from human time or digital time” (Fan, 345).

Figure 2: A screenshot from J. R. Carpenter, The Pleasure of the Coast: A Hydrographic Novel. 2019. Used with permission.**

Figure 2: A screenshot from J. R. Carpenter, The Pleasure of the Coast: A Hydrographic Novel. 2019. Used with permission.**

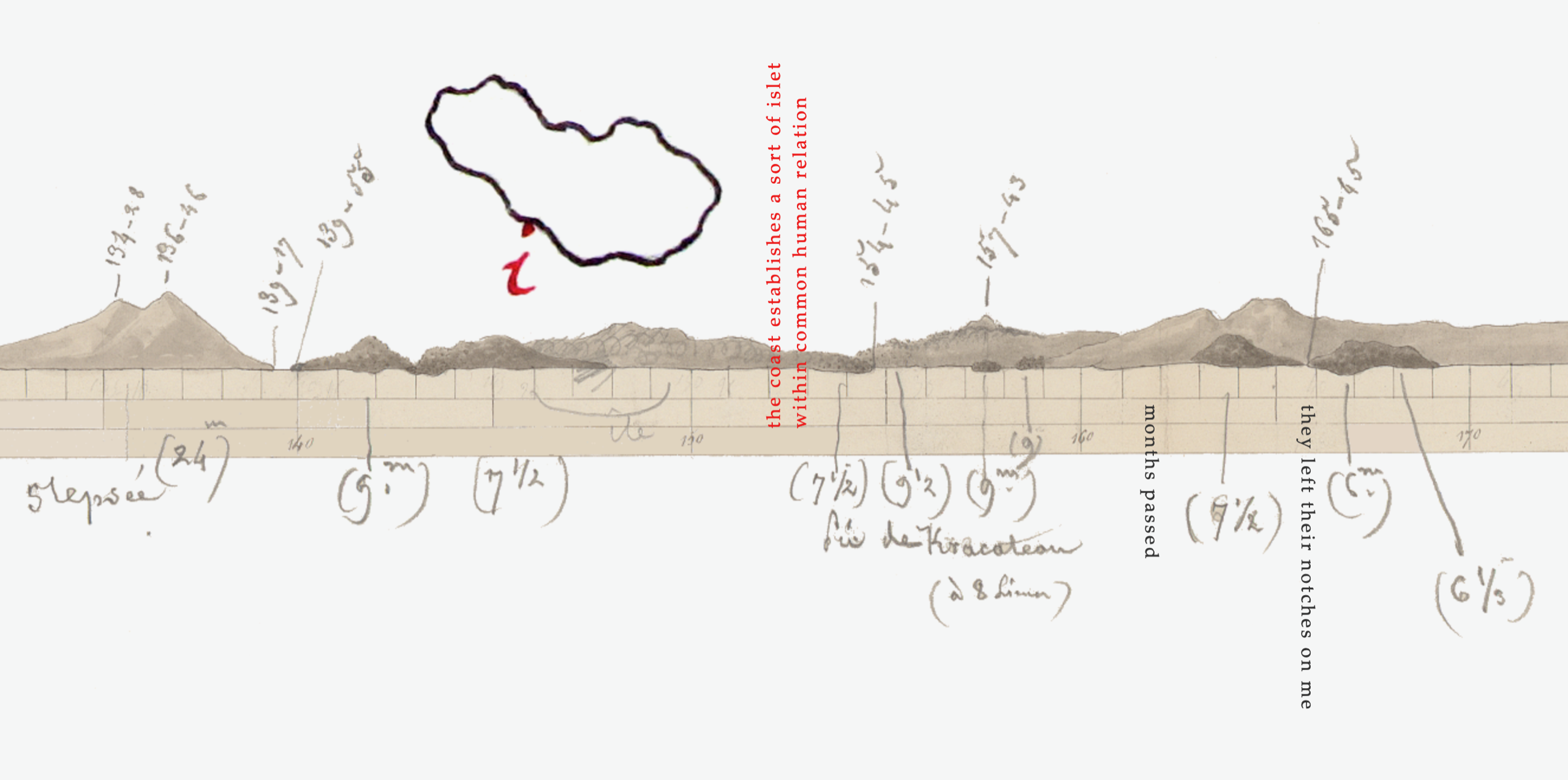

Indeed, the rescaling of questions of environmental perception, inscription, and thus even data onto material bodies, sites and historical contexts becomes one way of this expanded not-just-digital poetics of media ecologies. J.R. Carpenter’s various works stand out as an apt example, including The Pleasure of the Coast, which exists both as an online “hydrographic novel” (2019) and as a printed poetry book version (2023). The trope of the coast is anchored in a 1791 expedition that was joined by hydrographer Charles-François Beautemps-Beaupré, with its various media and technical inscriptions, and alongside questions of colonialism, accuracy and indeed, data capture, that are executed in pre-digital formats such as drawing. They thus feature as one example in the longer history of what, much later in digital culture, are defined as operational images (Parikka, Operational Images). Carpenter’s work addresses cultural techniques of observation as the backbone of knowledge production that also come to feature the possibility of errors and glitches. It shifts from the scientific to the anecdotal. Here, the coast is coined as “a sort of islet” (Carpenter, 17) which also becomes defined by its transportability as inscription. Or in Carpenter’s more subtle words quoted from the printed version (35)

what I enjoy in a coast is not directly its content or even its structure

but rather the abrasions I impose upon its fine surface

Data inscription becomes part of the narrativization of both the original context of hydrographic drawings and the genre of such data production that is brought back to concerns of digital poetics. Such environmental data about topographical features, geographical sites, and thresholds of water and land come to feature material histories of patterns and methods that create or reproduce such patterns––as drawing, performance, and contemporary art methods where questions of diagramming and movement have been developed in a related key. This entanglement of writing, imaging, and data as diagrammatic arts comes to stand as one example of the graphic method that also captures other contexts of elemental media, such as clouds and waves.

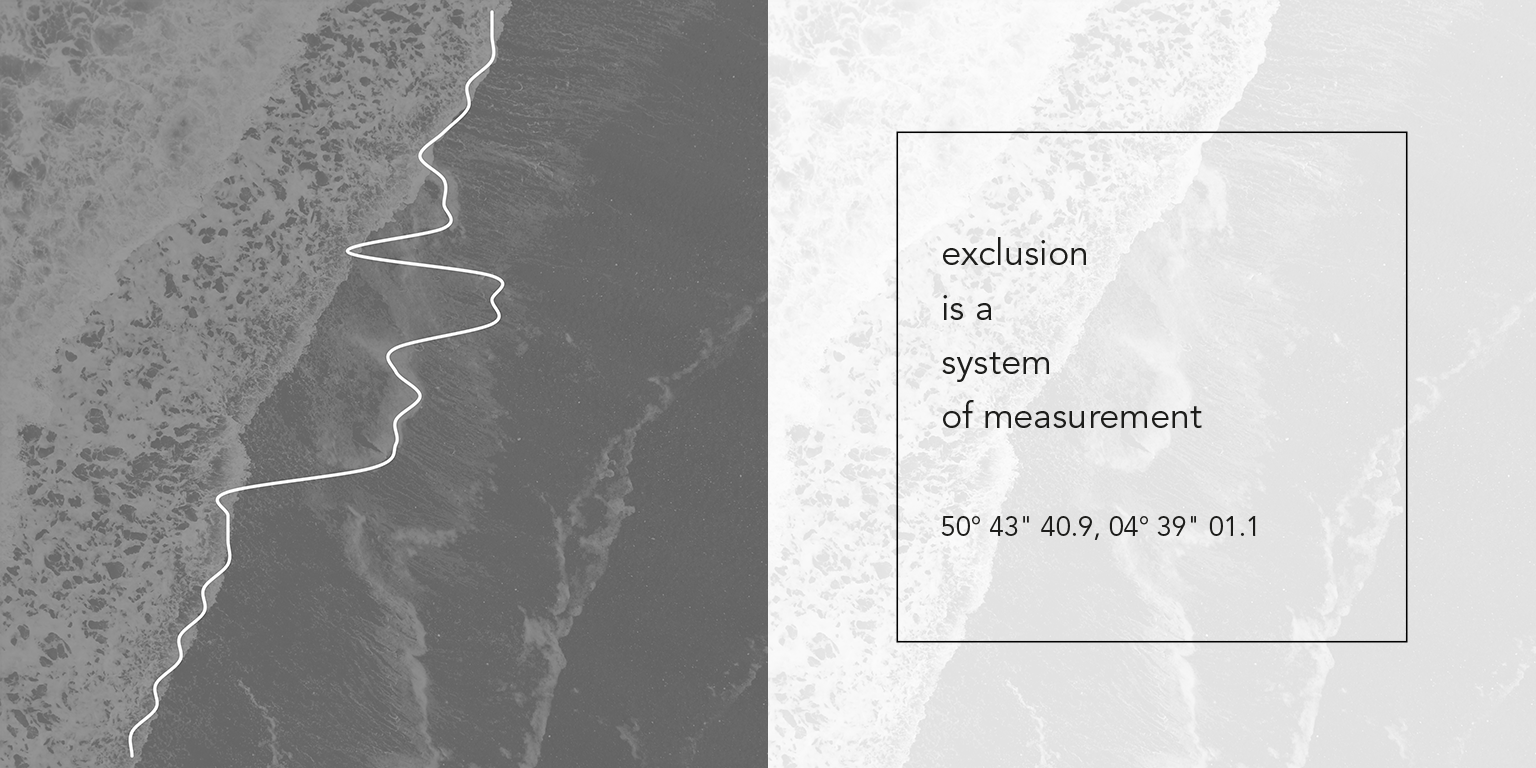

Richard Carter’s Waveform (2018, 2023) is an apt example of the latter: the drone view machine vision processing of the wave patterns hitting a shoreline (see Figure 3). Here, three layers of media and data inscription are conjoined: the film version as time-based registering of machine vision, the algorithmic processing of the threshold of the waves and the shore, and the patterns themselves that are one form of (ephemeral) autographic visualization of data (Offenhuber), a theme we return to in the next section. Digital poetics are centrally read in relation to the “site” of the shoreline, with the dynamic patterning of waves being one version of what Jane Hutton has in another context aptly phrased: “landscapes are models in-situ” (11). A similar theme features in Carter’s recent Line of Flight (2023), where dynamic volumetrics of wind become not only the content of the writing, but its material informant, the elemental media in which a particular ecological narrative emerges.

Considering questions of temporality, inscription, data, and digitality, Shelley Jackson’s durational performative writing project Snow (2014-) connects to our interest in elemental mediation. As an elemental media landscape piece, it weaves digital platforms to snow-enabled material inscriptions, offering a broader aesthetic framework for the sort of ecocritique our audio stories resonate with. Since January 2014, Jackson’s durational piece has featured images of words on snow on a dedicated Instagram profile. As Paul Benzon notes, this mode of inscription shows the double-materiality of inscription surfaces and platform aggregation. The post-digital work emerges in multiple recursive remediations “from the microscopic scale of the word, the typographic character, and the byte, to the macroscopic scale of global media and planetary climate” (70). Inscription and data are both materialized and abstracted as the images circulate and participate in platform economy. Indeed, one way to understand this would be through infrastructures, which can also include such varying patterns as weather, and their relation to the erasure of weather patterns, such as with climate change. As Benzon writes, “For Jackson, imagining the poetics of infrastructure is inseparable from imagining the infrastructure of poetics—both reside within the configurations of physical apparatus that sustain her project as well as the seemingly uncountable global traffic in digital information” (72). Any assumption of the naturality of weather, of environmental surfaces (urban or non-urban) and other elemental material contexts as separate from the technicalities of the Anthropocene, become problematized: it is instead more apt to claim that in this instance, the environmental media of writing surfaces such as snow is entirely infused in the artificiality of weather in the age of anthropogenic climate change.

Hence, as modestly implied in the Instagram tagline about the project – “weather permitting” – the ephemerality of landcover features alongside the horizon of extreme weather. The elemental media of such artistic work becomes temporal, temporary, and fluctuating. Landcover resonates with our narrative too, entangling the material with the production of stories. What Amitav Ghosh (16-20) has articulated about the mismatch between the statistical stability inherent in worlds of the classical novel and the increasingly freak events brought about by climate change puts this point into a broader literary context: a mismatch of storied realities is also the central hinge around which ecocritique needs to function as it shifts between background and foreground, between narratives and the infrastructure of such narratives. Ecocritique thus engages in the material circumstances where digital culture serves as a filter for insights into ecological poetics, as it is addressed within this article and in the Audiotour. Contingency and the anecdotal are central elements in this version of ecocritique: the grounding of (datafied) abstractions in fluctuating, partial sites of their material production comes to feature as one element in the recursive poetics of such mediations. (See also Fan; Carter, “Electronic Literature in the Anthropocene.”)

Another way to put this is to refer to Seán Cubitt’s point about anecdotal method for ecocritical knowledge. The anecdotal, Cubitt explains, puts together coincidence and condition, situation and its relation to the informational.

[…] anecdotes are ecological encounters, unique instances coming into being in the confluence of influences. Anecdotal truth is of a different order to scientific and political data. Anecdotes create an alternative to the dominant information regime with its claim to truth as universality and order. This is why anecdotes are so speedily excluded from discussions of policy, and equally why they are so important to the radical political agenda of ecocritique, which exceeds the human-centred idea of the environmental that surrounds and is excluded from humans. For ecocritique there is no boundary between humans and environment. There are only complex interweavings of conditions and situations. The conditions that make it possible for events to occur and stories to be told are the events and the stories. It is exactly their contingency–the unexpected results of criss-crossing influences and causal chains–that makes events real, and ground ecocritical politics.” (Cubitt, 3).

This position concerning material semiosis at the back of abstractions resonates with tendencies in critical data studies that investigate the geographies and assemblages of data. The locality and localizability of data is what, after Yanni Loukissas, can be focused on as a critical methodology for understanding the conditions of existence of broader digital projects of enumeration too. However, this also implies a broader, experimental stance that we are interested in teasing out with artistic and curatorial methods: could such urban and non-urban landscapes of polyphonic agencies be read as data in the first place? Could they be considered as pattern formation that translates into a materially embedded infrastructure in ways that carry the already quoted point about landscapes as models in-situ even further? Christian Andersen and Søren Pold have articulated the idea of metainterface as the process where (digital) interfaces withdraw from user operability to more environmental contexts and conditions; we are interested in a closely related point: that environmental conditions already exist as interfaces, as sensorial capacities, material affordances, and infrastructures in the assemblage of environmental mediations. Such works as Parikka’s A Geology of Media expanded notions of media to encompass the broader environment-infrastructure-energy nexus, and our version of this is to test out methods of narrativization that play with questions of spatial and temporal scale. The expansion of digital poetics beyond digitality has come to play a key role in many recent works, with the idea that computational cultures are dynamically interrelated to their landscapes and planetary affordances. These imaginaries of data and digitality focus on the question of how to sense sensing (to echo Chris Salter’s words in his recent take on the history of sensors) and offer stories that look at the broader spectrum of data cultures. As we emphasize in this article and in the audio episodes, these are not necessarily stories that feature explicit technologies, even though many engage with different levels of the artificial transformation of the environment, including architectures of artificial climate, which have become a planetary metaphor by the 2020s (as the botanic garden and the greenhouse) or the visible cues of energy infrastructures in transition.

Islands

https://soundcloud.com/helsinki-biennial-2023/ced-the-environmental-4?in=helsinki-biennial-2023/sets/helsinki-biennial-2023-critical-environmental-data-the-environmental-audiotour&utm\_source=clipboard&utm\_medium=text&utm\_campaign=social\_sharing Excerpt 2 The Weather Station

The post-digital mix of material landscapes, digital platforms and networked media relates to expanded modes of reading inscriptions and traces, including implied movement, and specifically walking. This theme has also been central to a lot of contemporary art over the past decades in multiple forms, and it further echoes experimental data visualizations that we will revisit later in this article. In contemporary art, besides many practices in land art that establish ephemeral or permanent marks and diagrams upon the earth’s surface, consider for example Ricardo Basbaum’s work on diagrams and visual poetry, which develops a cartographic approach treating writing and space as material and represented (Ribas). Beyond writing, diagrams become performed, relating to movement across urban space: Francis Alÿs’ walking performances investigate the ephemerality of tracing, as in Sometimes Making Something Leads to Nothing (1997), where a melting cube of ice is pushed across Mexico City. Friction Atlas (2014) by Paolo Patelli and Giuditta Vendrame visualized rules governing movement and behaviours in public space, directly on city surfaces and through crossings of the city. In resonating terms but with different methods, diagrammatic tracing that complexifies abstraction and physicalisation, Anna Zvyagintseva’s drawings are based on walking trails, non-symbolic but still fully meaningful and “data-rich” traces with a sensorial connection to the landscapes they express. In another register, the seed-laden ice books by Basia Irland, hydrological sculptures, melt back in river waters in a time-based experience of disappearance. These book-like objects are made of and disappear into their origins. Their typographic traces are made of seeds. Thus, from writing, the piece moves onto the sort of transport and transformation typical of river-based and other natural processes, as elemental mediations.

We were interested in mapping material and ephemeral traces as insights to the city and its islands. Especially the notion of “island” was a central conceptual and material theme for The Environmental Audiotour, itself premised on movement across different selected sites. The second episode of our series featured directly the Vallisaari island, a site that had gone through unintentional rewilding due to it being a restricted military zone (Bhowmik) while containing such architectures of environmental sensing as a weather station. While the station had also functioned as a meteorological training site, it is now only a site of ruins. However, it functioned as a non-site of sorts that connected questions of sensing, data, and speculative design. The island was formed into a whole data assemblage with anecdotal bits from its history–factual or fabulated–enmeshed together with an imaginary future plan.

The geographical and topographical context is evident in how the main Biennial site Vallisaari is a special island environment known for its military history (switching hands from Swedish to Russian and then to Finnish governance) as well as for its unique biodiversity of flora and fauna. Already during Helsinki Biennial 2021, artist Samir Bhowmik paid attention to this point of ecological sensitivity: both in his written work that offered a short environmental history of the island and in his participatory performance that approached the island as an ecological habitat through which to investigate histories and speculative stories of racial capitalism. The Lost Islands performance (and subsequent video documentation version) was a version of the infrastructural tour methodology (Bhowmik and Parikka, “Memory Machines”) that provided one reference point for our thinking about the island as consisting of multiple kinds of layers and routes, infrastructures, areas, zones, and habitats. We also expanded the trope of the island to the city: the city as a heat island, the Botanic Garden as an isolated climate-controlled “island”, and the artificial islands made from land reclamation were featured in the Audiotour.

This island hopping follows the sites as layers of traces, some of which are histories, some of which exemplify the points about noticing, sensing, categorizing, and care. The stories are thought through the ecocritical attention to conditions and contingencies. Our focus was on developing the narrative as situated ecocritique, informed both by subtle hints from the history of location and by its relation to the broader region, the Finnish Gulf. Part of the Baltic Sea, it is a significant body of water for various reasons: for being one of the most contaminated seas in the world (with agriculture chemicals from Finland and Russia, industrial and military waste), but also for geopolitical reasons due to its location, emphasized by recent events, from the Bornholm gas pipe explosion (September 2022) to the sabotage of the Estonian-Finnish gas pipe (October 2023). Any island or city surrounded by this sea is in some role implicated in these dynamics, a point that was taken into account also in the curatorial thinking, which had to relate to broader societal and international events.

In Anthropocene studies, the island has also provided a specific geographical site for analysis. As Pugh and Chandler argue, “Islands have become important liminal and transgressive spaces for work on the Anthropocene, both inside and outside the modernist world, both real and imagined, from which a great deal of Anthropocene thinking is drawing out and developing alternatives to hegemonic, modern, ‘mainland’ or ‘one world’ thinking.” (2). Such patches of focused interest resonate with how the idea of such “test-beds” (Calvillo, Halpern, LeCavalier, and Pietsch; Gugganig and Klimburg-Witjes) persist in various historical and contemporary climate narratives. Hence, the horizon of islands is thoroughly linked to their gradual disappearance, especially in many vulnerable areas, raising concerns relevant to international law (Stoutenburg), but also presenting the perspective of forced displacement and the emergence of planetary patterns of climate refugees. In some cases, such as Tuvalu, the gradually rising seawaters have triggered discussions about the creation of a digital twin of the area (Fainu), emphasizing the multidimensional nature of islands as proxies that generate proxies. The earlier colonial tropes of islands as Western Judeo-Christian imaginary topoi of rediscovered Eden (Grove) transformed into the logistical reliance on islands for the extraction of materials (such as wood) as well as the trade of goods and data (such as botanic samples), furthermore emphasizing the historical interest in these topographical features.

The three conceptual prompts of Contamination, Regeneration, and Agency were conceived by the curatorial team of the Biennial to feature at several scales. The curator Joasia Krysa referenced Anna Tsing’s point about the arts of noticing as the probing of scalar differences that can feed into a rich set of curatorial coordinates, both in concrete terms of spatial thinking with the artworks and in broader conceptual themes that helped us also to think of our Audiotour. The main title of the Biennial, “New Directions May Emerge”, was based on a quote from Tsing alongside this methodology of noticing as part of agency and contamination: a rehearsal of the senses as already always contaminated with others, and an investigation of how non-human anthropologies can inform spatial practices also in the curatorial sense. Hence the idea of approaching selected sites of the city as “multiple temporal rhythms and trajectories of the assemblage” (Tsing, 24) informed what kind of an entity the environment in this case should be: polyphonous layers of narratives, of imaginaries and real places. Our idea about ecocritique emerged from this form of assemblage thinking and noticing: it is perceived less as a genre of writing or film, but as an aesthetic, even ontological stance to mediation that emerges before human (or technological) mediation. This speculative question of ecocritique from the perspective of non-humans (Cubitt) was then an attempt to consider the agency of plants, soil, and atmospheres as part of the co-design of the urban and non-urban areas.

Such a stance to ecological fiction is thus aligned with what Buell argued in The Environmental Imagination about foregrounding non-human environment in ways that do not reproduce a separated binary of natural history vs. social history but are interested in how these various temporalities are co-present and narrated together. (Buell, The Environmental Imagination, 7-8; Fan, 343). As spatial tropes, this responds to Tsing’s note on the condition of life being about aftereffects or ruins of capitalism and industrialization, or how “we mostly do have to work within our disorientation and distress to negotiate life in human-damaged environments.” (Tsing, 131).

In this vein, our third excerpt from the six-part Audiotour focuses on the energy infrastructures of a city, or: how to narrate the environmental transformation and ecological transition from the point of view of the large pile of coal that characterized one part of Helsinki cityscape in and around Hanasaari until recently. It stood as a reminder of the obsolete fossil fuel legacies of the region. This, too, was seen as an island although one connected to larger planetary-scale infrastructures of energy transport.

The Autographic City

https://soundcloud.com/helsinki-biennial-2023/ced-the-environmental?in=helsinki-biennial-2023/sets/helsinki-biennial-2023-critical-environmental-data-the-environmental-audiotour&utm\_source=clipboard&utm\_medium=text&utm\_campaign=social\_sharing Excerpt 3 Hanasaari Coal Power Station

To narrate cities through non-human eyes echoes different contexts of literary and cinematic writing across the past 100 years. From cinematic city symphonies (to which we will return at the end) to more recent eco- and digital poetics that summon the non-human and the Anthropocene (Cohen and Duckert), the multiscalar perspective is a significant part of how to mobilize the anecdotal method as we do in our Audiotour productions. In our case, it comes to feature a role where stories and sites are tied together although constantly thinking in terms of scales of experience and impact, sorts of “mines of flight” to use a term from Lowell Duckert’s (256-260) writing on coal’s agential role. Here, coal becomes an ephemeral trace. In more specific ways, it refers to tracing or a tracer substance that highlights passages through landscapes, cities, and infrastructural routes.

Considering coal, we wanted to think of both the travels and perspectives of coal particles – a hint of airborne visualization and aggregation of dust– as much as we saw the coal pile outside the now decommissioned Hanasaari power plant as an urban landscape island that “measured” the energy use of the city in reverse as the coal pile every year reduced by the summer. Our interest in the infrastructures of green transition was a context for the narrative, while the acute emergency that followed the February 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, with the ensuing energy crisis across Europe, intensified this concern, extending it to geopolitical (energy) security. Much of the knowledge base around energy features in technoscientific narratives of datafication, where modeling exists as a horizon of a different scale of environmental aesthetics: emission models are connected to geopolitical (supply and demand) models, that meet logistical modeling of supply chains, that meet and recursively repeat in different modes of financial modeling.

While such models and abstractions are one core aspect of “data visualization” of environmental patterns, the other part about traces and data physicalization brings some of these questions back onto material surfaces and landscapes. Here, the notion of trace is closely linked with the forensic and investigative aesthetics as outlined by Matthew Fuller and Eyal Weizman as well as Susan Schuppli. Furthermore, the particular design strategies of this mode of reading/writing inscriptions are well framed by Dietmar Offenhuber’s notion of autographic visualization. To approach and frame traces across different scales of the city was a constant reference point in developing our anecdotal ecocritical Audiotour that also thus established the link to an alternative data poetics. Here, the idea of coal as one visualization of the city functions as a narrative frame and also a methodological device to understand large-scale spatial transformations as part of broader discourses of technology.

Offenhuber’s description of autographic visualization draws on the history of the graphic method, an example of data visualization that has often been featured in media archaeological work concerning early cinema. Different apparatuses for self-inscription of rhythms, pulses, and movements of living organisms, from humans to horses and other animals, came to play a key role as early laboratory practices of producing and reading inscriptions. Étienne-Jules Marey’s methods of visualization are frequently cited as an example along with many other instruments and apparatuses of physiological research, or for the measurement of weather through analog means: cyanometers for blueness of the sky, anemometer for wind speed, etc.

Autographic visualization works on the centrality of the trace as part of how design operations can tease out historical inscriptions as data. Implicitly again echoing the idea of landscapes as models in-situ (Hutton), the operations aggregate, frame, or otherwise visualize airborne particles of air pollution, chemical patterns in water, or other elemental media made visible with tracer substances. They might also operate through existing surfaces to demonstrate the presence of seemingly invisible processes that become readable, so to speak, with the particular framing of a material data analysis. For example, Offenhuber’s Stuttgart-based project, Staubmarke visualizes pollution by aggregating dust into “reverse graffitis”. This sort of marking of the built environment is one version of aggregated visualization, even if not numerical or symbolic. This technique of reading/writing is based primarily on framing, as well as on the comparison of inscriptions. It also resonates with experimental techniques such as data physicalization and data visceralization (Offenhuber, 41-43), where different material, geometric, physical, or embodied scales and bodies of sensing become recognized as part of an aesthetics of knowledge. Data visualization is reframed through existing material visualizations that can be thus made into operational surfaces, extending what is usually the data imaginary inherent in digital poetics to the broader inscription surfaces and instruments. 2 While in this case the graffitis tag different sites of the city, one could imagine such a marking at the scale of the city at large: large-scale graffitis of traceable processes, e.g. coal dust, that start to define the autographic city – a city inscribing, even archiving, its own processes – and the potentials of how to narrativize this trace as an expanded part of digital poetics and ecocriticism. As the sixth episode of the Environmental Audiotour put it, “we could visualize the air through coal’s voluminous presence. As the skies seem to clear in our eyes, we can still trace the contours of the winds and the invisible edges of our atmosphere by following coal’s smallest forms which escape our shells of shielding or insulation. Coal lingers on even as the city attempts to bid it adieu. It is the city’s ghostwriter that cannot be contained and told where to go.” Such a writing appears in the medium of prosopopeia as one expression of elemental mediations.

Similarly, as dust has been conceived as one form of mediation, a trace of the Anthropocene (Parikka, A Geology of Media), the points resonate with other recent notes in media theory: these include radical mediation (Grusin), ecocritique as primal mediation across the nature-culture divide (Cubitt) as well as the extension of understanding semiosis outside of human writing, as N. Katherine Hayles points out in her recursive reading of biosemiosis and cybersemiosis. The double decentering of humans as the only meaning-making entities takes place through the biological and the computational, which unfold as part of an extended cognitive apparatus at play: this differs from such accounts that replace computational metaphors with natural processes while acknowledging that digitality is not restricted to the strictly technological media in question. The material infrastructures of semiosis expand across a broader material field of meaning-making. In our case, this is teased out through the spatializing tropes of ecocritique, where data and architecture, infrastructure and sensing become some of the axes in the expanded post-digital culture of The Environmental Audiotour. A multitude of sign systems and semiosis runs across each other, offering infrastructural support that also feedback into the environment: the epistemic filters through which we understand the environment through notions of information or data become the prevalent format of how we tell stories and how we count natures.

So when John Durham Peters writes, discussing Ralph Waldo Emerson, that “nature has meaning, but not for us” (379), it should be extended into the broader universe of semiosis: nature has meaning beyond us, as does computational culture too. This is why many of the examples cited from electronic literature and its expanded materialities are deeply entangled with the ecocritical angle we present. Jackson’s Snow stands again as an exemplary project to think with, as it implies abstraction not only through platform aggregation. The writing itself is embedded in surfaces of inscription that are both machine readable – to echo Richard Carters’ take on multiple layers of programmed environments that recursively feedback to our vision of “natural” surfaces too – and it is already a deep entanglement of other inscriptions as far as snow as elemental media is about aggregated frozen water crystals full of chemical traces of the Anthropocene weather and climate, of trace metals, chlorides, persistent organic pollutants (POPs), and so forth.

Concluding with the city, we feature our final excerpt that returns to ecocritique by way of cinematic ecomedia. Saaret (2023) (Islands) was shot and edited by Paolo Patelli from our research group. Building on the Audiotour texts, it presents a version of the city symphony films that defined the modern technological cityscapes in the early part of the 20th century. Early examples of the link between moving image and the technological pre-digital city would be Walter Ruttman’s Berlin: Symphony of a Great City (1927) and even in some ways Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929), which instead of focusing on one city, featured Kyiv, Moscow, Odessa and Kharkov, through the impersonal agencies of the machine vision of the camera. In our case, Tsing’s points about polyphonous assemblages are mobilized in the film, as we are interested in how this site-specificity can help us to approach expanded digital culture, infrastructures, and more importantly, practices of sensing as elements of the creative data assemblage. The film (shot in super-8, with sound design by composer Angelo Maria Farro) foregrounds the fragility of the image frames as it pairs up with our broader ambition to narrate existing and imaginary histories of elemental media as urban and non-urban landscapes; islands to coal piles to other artificial formations come to feature as proxies of Anthropocene atmospheres. Methodologically, the overall aim of the Audiotour is also present in the film: that the environment contains elements of its own measuring, as well as stories that emerge from those measurements, and contingencies that become visible in such materially thick sets of “data”. As such, the film is guided by the same set of navigational elements present in the Audiotour diagram (Figure 1).

While presented as creative works, both the film and the Audiotour are also practice-based engagements with contemporary research in terms analyzed in this article. Such ecomedia mobilize existing and imagined histories of weathers and climates to frame a sense of the atmospheres we exist in; the urban and non-urban environments expressed in the stories also conjure alternative environmental data imaginaries that work across current digital poetics while also presenting suggestions on method. Contemporary art methods, curatorial practices, as well as engagement with broader citizen publics, present this project as a response to Cubitt’s point about anecdotal method. It is thus a continuation of how public-facing projects can articulate multi-scalar, polyphonous environmental realities. Site-specific storytelling becomes one way of mapping sites of environmental sensing and design across different scales of knowing. This is part of a post-digital narrative, fully embedded in technological worlds, yet articulated through sites, architectures, and recursive patterns of sense and sensing.

https://vimeo.com/929361380 Excerpt 4 Saaret / Islands film

Acknowledgements

The work for this article was supported by the AUFF grant Design and Aesthetics for Environmental Data (Aarhus University, 2022-2024).

Works Cited

Anders, Christian Ulrik and Søren Bro Pold. The Metainterface The Art of Platforms, Cities, and Clouds. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press 2018.

Benzon, Paul. “Weather Permitting: Shelley Jackson’s Snow and the Ecopoetics of the Digital.” College Literature, vol. 46 no. 1, 2019, p. 67-95. https://doi.org/10.1353/lit.2019.0002.

Berry, David and Michael Dieter, eds. Postdigital Aesthetics: Art, Computation And Design. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

Bhowmik, Samir. “From Nature to Infrastructure: Vallisaari Island in the Helsinki Archipelago.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Summer 2020), no. 28. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/9062.

Bhowmik, Samir and Jussi Parikka. “Memory Machines: Infrastructural Performance as an Art Method.” Leonardo 2021; 54 (4): 377–381. doi: https://doi.org/10.1162/leon\_a\_01998

Bhowmik, Samir and Jussi Parikka, eds. Environment, Data, Contamination. Helsinki: Taideyliopiston Kuvataideakatemia, 2023. Online open access at https://taju.uniarts.fi/handle/10024/7846.

Buell, Lawrence. The Environmental Imagination: Thoreau, Nature Writing, and the Formation of American Culture. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1995.

Buell, Lawrence. The Future of Environmental Criticism: Environmental Crisis and Literary Imagination. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell, 2005.

Calvillo, Nerea; Halpern, Orit; LeCavalier, Jesse; Pietsch, Wolfgang. “Test bed as urban epistemology” in Smart Urbanism. London: Routledge, DOI: 10.4324/9781315730554-10.

Carpenter, J.R. The Pleasure of the Coast, online hydrographic novel, 2019, https://luckysoap.com/pleasurecoast/en/index.html.

Carpenter, J.R. Le plaisir de la côte / The Pleasure of the Coast. London: Pamenar Press, 2023.

Carter, Richard “Waves to Waveforms: Performing the Thresholds of Sensors and Sense-Making in the Anthropocene” Arts 2018, 7(4), 70; https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7040070

Carter, Richard A. “Electronic Literature in the Anthropocene”, Electronic Book Review, May 3, 2020, https://doi.org/10.7273/rt06-ts14.

Cohen, Jeffrey Jerome and Duckert, Lowell, eds. Elemental Ecocriticism Thinking with Earth, Air, Water, and Fire. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015.

Cubitt, Seán. Anecdotal Evidence Ecocritiqe from Hollywood to the Mass Image. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020.

Duckert, Lowell. “Earth’s Prospects” in: Elemental Ecocriticism, eds. Cohen and Duckert. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press 2015, 237-267.

Fainu, Kalolaine. “Facing extinction, Tuvalu considers the digital clone of a country.” The Guardian, 27 June 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/jun/27/tuvalu-climate-crisis-rising-sea-levels-pacific-island-nation-country-digital-clone.

Fan, Lai-Tze. “Digital Nature”, in Nature and Literary Studies (2022). Cambridge University Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108872263.023.

Fuller, Matthew and Eyal Weizman. Investigative Aesthetics. Conflicts and Commons in the Politics of Truth. London: Verso, 2021.

Gabrys, Jennifer. Program Earth. Environmental Sensing Technology and the Making of a Computational Planet. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016.

Ghosh, Amitav. The Great Derangement. Climate Change and the Unthinkable. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016.

Grove, Richard. Green Imperialism Colonial Expansion, Tropical Island Edens and the Origins of Environmentalism, 1600–1860. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Grusin, Richard. “Radical Mediation.” Critical Inquiry 2015 42:1, 124-148.

Gugganig, Mascha, and Nina Klimburg-Witjes. “Island Imaginaries: Introduction to a Special Section.” Science as Culture 30 (3), 2021: 321–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/09505431.2021.1939294.

Hayles, Katherine N. ” Can Computers Create Meanings? A Cyber/Bio/Semiotic Perspective” Critical Inquiry 46 (Autumn 2019), 32-55.

Hutton, Jane. Reciprocal Landscapes. Stories of Material Movements. London and New York: Routledge, 2020.

Kitchin, Rob and Lauriault, Tracey. “Towards Critical Data Studies: Charting and Unpacking Data Assemblages and Their Work”. The Programmable City Working Paper 2; pre-print version of chapter published in Eckert, J., Shears, A. and Thatcher, J. (eds) Geoweb and Big Data. University of Nebraska Press, 2014. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract\_id=2474112

López, Antonio. Ecomedia Literacy. Integrating Ecology into Media Education. New York and London: Routledge, 2021.

Nylander, William. “Les Lichens Du Jardin Du Luxembourg.” Bulletin de la Société Botanique de France, 13, 1886, 364-371. https://doi.org/10.1080/00378941.1866.10827433

Närhinen, Tuula. “Do It Yourself, Rain! Dabbling Drops, Splashes, and Waves: Experiments in Art and Science.” Leonardo 2022; 55 (6): 627–634. doi: https://doi.org/10.1162/leon\_a\_02280

O’Dair, Sharon. “Muddy Thinking” in: Elemental Ecocriticism, eds. Cohen and Duckert. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press 2015, 134-157.

Offenhuber, Dietmar. Autographic Design. The Matter of Data in a Self-Inscribing World. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2023.

Parikka, Jussi. A Geology of Media. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015.

Parikka, Jussi. Operational Images. From the Visual to the Invisual. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2023.

Peters, John Durham. Marvelous Clouds. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015.

Pugh, Jonathan and David Chandler. Anthropocene Islands: Entangled Worlds. London: University of Westminster Press, 2020. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1v3gqxp

Raley, Rita. ""Living Letterforms”: The Ecological Turn in Contemporary Digital Poetics.” Contemporary Literature, Vol. 52, No. 4, (Winter 2011), 883-913.

Ribas, Cristina. “Cartography as Research Process: A Visual Essay.” In response to Sohin Hwang and Pablo de Roulet, ‘Bibliography(chorème)=’ OAR Issue 1 (2017). OAR: The Oxford Artistic and Practice Based Research Platform Issue 1 (2017), http://www.oarplatform.com/cartography-research-process-visual-essay/.

Salter, Chris. Sensing Machines. How Sensors Shape Our Everyday Life. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2022.

Schuppli, Susan. Material Witness. Media, Forensics, Evidence. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2020.

Starosielski, Nicole. 2019. “The Elements of Media Studies.” Media+Environment 1 (1). https://doi.org/10.1525/001c.10780.

Stoutenberg, Jenny Grote. Disappearing Island States in International Law. Leiden: Brill, 2015.

Tsing, Anna. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2021.

Footnotes

-

The possibility of evaluation of the success or failure of this task is an important one. We were not able to gather detailed enough data on audience responses, being only reliant on individual feedback, including from a well-known Finnish historian of meteorology (and inhabitant of Helsinki) who was fascinated about the intermingling of current and historical episodes, fact and fiction. However, besides the important question of how effectively we were able to reach the general public, our close collaborating participants of the student group were involved in the methodological discussions early on and their own work addressed related issues. Hence, their methodological training as artists was present in the parallel group show at University of Arts in June as well as written up in the book Environment, Data, Contamination (eds. Bhowmik and Parikka) that itself documents some of the creative reuses of related art methods with questions of data and ecology. ↩

-

We can understand Tuula Närhinen’s work at the Helsinki Biennial in these terms too, visible in both of the pieces exhibited: The Plastic Horizon (2019) and Deep Time Deposits: Tidal Impressions of the River Thames (2020). Her fieldwork of collecting plastic waste from an island in Helsinki is both about field methods and their organization into an autographic visualisation of sorts: The Plastic Horizon builds a visualisation from the ground up, from existing material pollutants of a landscape that themselves become their own signs. In addition to such pieces, a specific trace-like accuracy comes through in her other work like the Wave Tracer device that diagrams underwater pressure waves onto a rubber membrane, creating a version of the ”graphs” in the spirit of earlier mentioned graphic method. Similarly, rethinking the Baltic Sea surface as a screen media in the Wave Screen: “the surface of the sea was mobilized to serve as convex and concave lenses, which projected caustic wave patterns on the picture plane of a black box equipped with a translucent screen” (Närhinen 629). ↩

Cite this article

Parikka, Jussi. Paolo Patelli, and May Ee Wong. "Ecocritique between Landscape and Data: The Environmental Audiotour" Electronic Book Review, 7 April 2024, https://doi.org/10.7273/dhew-2166