Gaddis Centenary Roundtable - Artists in Non-literary Media Inspired by Gaddis

This roundtable discussion chaired by Ali Chetwynd, featuring artists Stef Aerts, Thomas Verstraeten, David Bird, Edward Holland, and Tim Youd took place at the Gaddis Centenary Conference in St Louis, on October 21st 2022. It has been lightly edited for clarity. Transcript by Marie Fahd.

The Artists and Their Artworks

Edward Holland (Visual Artist)

As a series-based artist, I like to explore a theme, whether it is formal or conceptual, across many works of art over a period of time. This current series, Vigils of the Dead, began in 2014 and is my longest running series. It is named after the working title for Gaddis’s The Recognitions. Initially I had wanted to do a body of work about the book, but it was too much to get a handle on. Perhaps one day I will be able to do so, but I am not ready at this moment. I like to honor the connection when I can, hence Vigils of the Dead. I also title every solo show from this body of work after a line from the book. Little gestures.

Instead, I settled on one aspect of that book: mythology. The mythology that Gaddis grafts into The Recognitions resonated with me. That was the original point of departure. I have always been in love with mythology and myth-making and wanted to build a body of work that dealt with both without being illustrative. The paintings could not be literal. They could not be translations. The work needed to be open to interpretation and be abstract. A Zodiac sign, I realized, is exactly that: an abstract shape signifying a narrative. It is form and content. The same can be said of Painting itself. The overlap of the two can be pushed even further in that both, the Zodiac and Painting, are systems for delivering information that now could be considered obsolete. The Zodiac is relegated to telling us what will happen during our day and Painting is no longer the way people understand the stories of the Bible.

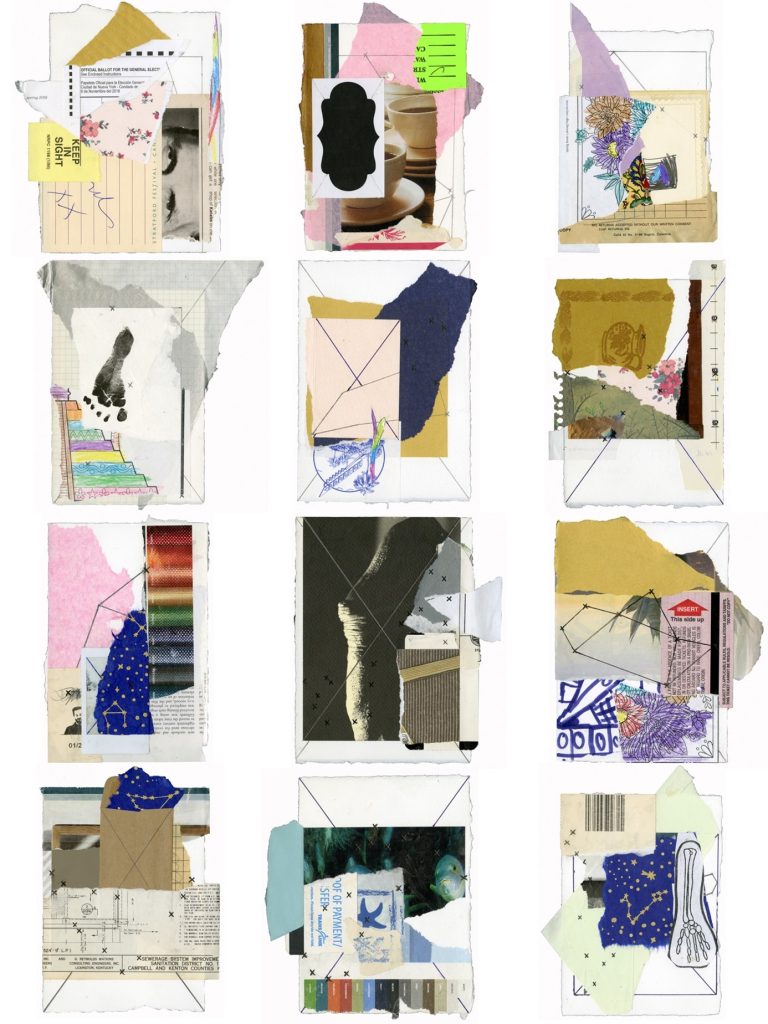

Embedded within each piece is a Zodiac sign – not a picture of a bull or of a fish, but the positions of the stars. This is the challenge that each work presents: how to make an interesting and unique work of art while dealing with the same set of circumstances. The stars themselves are almost always represented by small Xs placed across the work. Sometimes the sign is obvious and appears to float above the image and other times it is deeply obscured by paint and collage (see Figure 1 for a relatively early example).

I allow the Zodiac sign to govern other aspects of my process as well. Choices regarding color are based on which color (or its opposite on the color wheel) is associated with that particular sign (Aries = red, etc.). I filter my choice of collage elements through the sign. If something is torn from an anatomy book, I make sure the body part is ruled by that particular sign.

While I have always used collage in my work, I do like the overlap with Gaddis’s use of “collaging” existing texts into The Recognitions. I think that every person has their own unique set of understandings, memories and feelings which cloud their reading of any artwork – whether it is a book or a painting. Abstraction and collage feed into that. The viewer reconciles the gesture, the color and the scrap-of-paper-with-a-picture-of-a-girl-smiling into some new understanding of the painting. And each time they look at the painting, it can be different. That openness of interpretation has always driven my work.

In this more recent small suite of works on paper, The Depot Tavern Series, I wanted the collage to be the focus (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: The Depot Tavern Series, 2020, Graphite and ink on paper with collage, 7 x 5 inches each approximately [twelve panels], Courtesy of the artist and Hollis Taggart Gallery, New York

Similar to Gaddis’s use of found conversation and found text within The Recognitions, it is texture hinting at deeper truths. I made this series during the summer of 2020, while spending Covid lockdown in the mountains of Western North Carolina. The small, provisional studio I made for myself in the lower level of the cabin where my family and I were living became my daily retreat. I named it The Depot Tavern, and it was fresh out of griffin’s eggs.

Figure 2: The Depot Tavern Series, 2020, Graphite and ink on paper with collage, 7 x 5 inches each approximately [twelve panels], Courtesy of the artist and Hollis Taggart Gallery, New York

Similar to Gaddis’s use of found conversation and found text within The Recognitions, it is texture hinting at deeper truths. I made this series during the summer of 2020, while spending Covid lockdown in the mountains of Western North Carolina. The small, provisional studio I made for myself in the lower level of the cabin where my family and I were living became my daily retreat. I named it The Depot Tavern, and it was fresh out of griffin’s eggs.

David Bird (Musician and Composer)

“Saloon Wars,” which you can listen to here—http://davidbird.tv/saloon-wars—is a composition written for 4 Disklavier Pianos and Electronic Sounds in 2014. It was initially composed for Qubit New Music’s “Machine Music Concert” at the Clemente Soto Vélez Cultural Center in the Lower East Side, New York City. This concert provided a wonderful opportunity to write for the Disklavier, a modernized version of the player piano, which replaces the traditional paper piano roll with a computer-based DAW (Digital Audio Workstation). Given the chance to write for this ‘digital’ player piano, I was reminded of William Gaddis’s writings on the player piano. Gaddis expressed concerns about the increasing mechanization of art and commerce, and I felt that these sentiments resonated with some of the issues faced by contemporary artists working at the intersection of art and digital technology. These concerns include worries about copyability and artificial intelligence.

“Saloon Wars” is a reflection on themes of copyability and artificial intelligence, as well as an exploration of the role of technology in my creative practice. As an artist who utilizes computers in my work, I found myself questioning the tropes and pitfalls I encounter in my artistic process and how digital technology can both complement and hinder my artistic instincts. The work serves as a creative exploration of the impact of digital technology on artistic expression and the potential consequences of an increasingly automated artistic landscape. Several zany and Westworld-inspired themes emerged while working with these instruments and materials. These themes came to influence both the title of the piece and its dramatic arc. In my program note for the work, I describe a post-human sci-fi scenario where player pianos remain as the sole remnants of human civilization. Consequently, the “Saloon War” depicted is not a confrontation between humans but rather a showdown between the player pianos themselves.

My composition “Drop”— http://davidbird.tv/drop—is also inspired by Gaddis as the website text explains, though I didn’t play it at the Gaddis conference.

FC Bergman (Theatre and Performance Company)

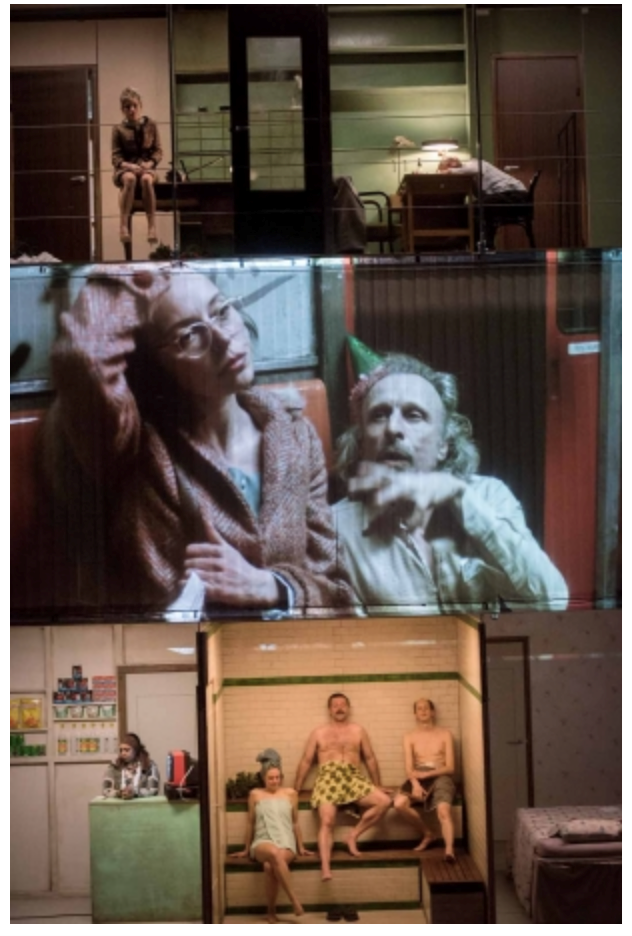

FC Bergman adapted J R for the stage, giving multiple performances between March 2018 and March 2020, in Antwerp, Ghent, Brussels, Amsterdam and Paris. The performances were also filmed (from inside the set), as live video was an important part of the stage presentation.

Performed in the round with the audience seated on four sides of the stage, J R was performed on a four-level tower with sets built onto all four sides (see Figure 3).

Scenes were acted concurrently on differing sides of the tower whenever they were meant to be happening simultaneously in the narrative, with video projections (on a screen that could be raised or lowered to reveal more sets) on each side when the acting was happening on the other side of the tower (See Figure 4).

Performances lasted four and a half hours, and despite some excisions covered the entire narrative arc of the novel.

While there are currently no publicly available recordings of the play (apart from some trailers created by the hosting theatres that remain online as of March 2024), a book of photographs from performances and staging, by the theatre photographer Kurt van der Elst, was published in 2019 by JardinCOUR.

Tim Youd (Visual and Performance Artist)

I am engaged in the retyping of one hundred novels, which has included a number of novels by Gaddis. I retype each novel on the same make or model of typewriter used by the author and in a location significant to the subject novel. Further, I retype each novel on a single sheet of paper, backed by a second sheet, that I run continuously through the typewriter. The words of the novel become illegible as the paper passes repeatedly through the machine. Upon completion, the two deeply distressed pages are separated and mounted side by side in a diptych (see Figure 5).

The entire novel is present but unreadable. As of August 2023, I am 10 years and 79 novels into my 100 Novels Project.

This project led to further Gaddis-influenced work, the Recognitions series of drawings and paintings, which began during the Covid quarantine. At the time, I was retyping back-to-back Gaddis’s J R and The Recognitions from my garage on a live-stream. These retypings were tied into the NYRB relaunch of both of those titles. I would type during the day, and in the evenings I would relocate to my kitchen table to work on my drawings. The subject of the drawings was the typewriter ribbon and spools (see Figure 6).

At a certain point during the Gaddis retyping, the Cristin Tierney Gallery of NYC organized a public Zoom event to talk about my work. The host was Claire Gilman, Chief Curator of The Drawing Center. The panelists, in addition to me, were Joel Minor, from Washington University Olin Library Special Collections, where the Gaddis Papers are, and Allison Unruh, who is an independent curator and the former contemporary curator at the Kemper Art Museum at Wash U. In my preparation for that event, I wound up revisiting my interest in Illuminated Manuscripts, and saw a path forward for my drawings to become much more elaborate while still employing the motif of the typewriter ribbon and spools. That recognition, so to speak, has driven this body of work for a few years now.

The Discussion

Ali Chetwynd: So having seen and heard the artists’ art, we move on to the roundtable side of things. I’ll ask you artists a couple of questions and give you a chance to ask each other some questions. Then, it looks like we have audience questions ready to go, so I’ll get on as quickly as possible. First question: what struck you most about each other’s work, having seen and heard about it just now? You all mentioned the kind of ways that Gaddis had influenced you and your work. So, hearing other people talking across their different media, what struck you as similarities or thing you had in common with other people? Or something about your experience and your relationship with Gaddis in your work that was different? What is it like hearing about other people’s relation to Gaddis through their artworks in other media? David Bird: I enjoyed seeing the amount of collage that was present. Looking back at my own piece, I did not realize how much of that, as a technique, was important for what I was doing, as I was not thinking about collage. At some point, I did read The Recognitions and I was aware of the multiplicity of layers in things. It was neat to see different layers and different approaches to collage and superposition in the works.

Edward Holland: What I really enjoyed is how we have all hitched onto one idea or aspect and allowed that to then become this sort of threshold. Once we get through it, then all of a sudden, that idea opens up and we can start pulling and adding things to it. But it always starts with this one initial sort of fixation, being Gaddis, that then we can open up to everything else. It is interesting to me to see what everybody else focused on.

Ali Chetwynd: What about you, Tim, Stef and Thomas? Stef Aerts: I think it is interesting that it all has something quite neurotic in it.

Members of the roundtable burst out laughing. Stef Aerts: I think that is very moving and very touching in a way, this attempt to reach for a bigger truth that is already in the novel itself, or in the novels, also in The Recognitions probably but I have not read it. It is nice. It feels a little bit like the “neuroticness” of William Gaddis is contagious in a way. It is a little bit edgy to talk about a nice way of contagiousness mainly in this area. But it is, I think.

Ali Chetwynd: And Tim? Tim Youd: It is certainly exciting for me to see these experimentations in other media. As artists, we think in certain directions. We are always trying to expand ourselves but, you know, ultimately you have to sort of bare down what captivates you and, all of a sudden, be shocked in other points of view on Gaddis. Today, it is really thrilling for me to think about different ways of approaching the work and the man behind the work, ways that are just brand new to me. That has been an exciting hour for me.

Ali Chetwynd: Cool. My second question was I guess about representationalness. Edward, you said that you wanted your things to be non-illusory – “non-illustrative,” was that it? Edward Holland: Yes, non-illustrative.

Ali Chetwynd: That’s it, and then David we might naturally expect music to be less representational. But it sounded like you had quite definite ideas that your piece is essentially narrativizing things - like conflicts between some identifiable number of combatants in the “Saloon Wars.” I wondered when it comes to the way that you drew on Gaddis, how did all of you balance representational and non-representational responses: from being struck by something more abstract like the style of Gaddis or the vibe of Gaddis, compared to – I suppose it might be especially direct for the FC Bergman people – particular things where you just had vivid images or representational ideas immediately in your head as soon as you read. In your reading of Gaddis, how do the non-representational and the representational interact? Those two poles, how did they filter through into your artwork? Edward Holland: Gaddis is so good at setting those scenes and setting that mental image that, for me, I immediately had to work against that. I did not want to go near it because it is too good as it is. So, I want to be in a completely different sphere than where he is. For me, it was to make it abstract, make it geometric, make it all these things that don’t feel lived in the way his novels feel so lived in. What I think is interesting for FC Bergman is that the scene you guys showed of 96th Street is exactly how I pictured those scenes in my mind. With crap everywhere, all over in the floor, in that freneticism. And so, for me, it was really exciting because it just reinforced that. I think it is cool that you guys can lean into it. You could then take it to that absurd place and keep pushing further and further and further in a way that makes the book feel much more literal if that makes any sense. But for me, I needed to get away from the literal and avoid the illustrative.

David Bird: Yeah, it’s funny now thinking about it because The Recognitions is such a vivid work, and I have these really clear images in my head that I don’t have with Agapē Agape because of the way that novel is structured. So I definitely felt like I was being convinced of certain ideas in the book, and those ideas manifested in the narrative that was kind of my own making… but definitely, I was being convinced by someone else and channeling that certain unhinged energy you were talking about. I wonder if I would ever approach The Recognitions in a musical sense. I don’t even know how I would do that; it’s such a captivating work in terms of visual representation.

Ali Chetwynd: What about FC Bergman people and Tim? Any thoughts on the representation versus the non-illustrative “vibe” distinction and how that plays out in your work? Thomas Verstraeten: We definitely went for the representation and we wanted to revive this world of J R and this world of Gaddis with as many means as possible, in film and in theater. We really went completely for these worlds and atmospheres. We made it actually as concrete and as literal as possible and made the characters as human and as alive as we could ask our actors to be. This was not an abstract work at all. We were really trying to create these worlds of Gaddis on stage. That was from the beginning our aim, let’s say.

Ali Chetwynd: I think that the way you talked about this experience of being on the other side of the tower, it seems that that was something where you were trying to get people to have the feeling of overwhelmedness or the sort of uncontrol that you get as readers of J R which is not straightforwardly just reducible to “observing some characters doing something,” like a simpler “transparent” staging might aspire to. Thomas Verstraeten: That is definitely true. We were really looking away to put the audience in the position of the reader but also in the position of our main characters, of Edward Bast and Jack Gibbs, so that the audience could also drown into too much of everything, too much of information, too much of life. So, I think that was something really important. The fact that the audience could feel exactly the same as our characters but also as ourselves when we went to work.

Ali Chetwynd: How about you, Tim? Tim Youd: I mean I understand that my diptychs appear abstractions but, for me, they are really and truly literal. It is every word of the book. In its own way, it is a direct representation of the book. It is the entire thing. That is why I kind of think of it as a drawing of the book. But, you know, of course it does not read that way when you look at it at first. It is only as you come to it, I guess, perhaps understanding what I had done, it starts to appear less abstract. I think that’s what runs through the typewriter ribbon in the spool drawings as well because more often than not those don’t get read as literally typewriter ribbons in a spool. They are perceived as abstractions. So, I think I probably like to sit in a spot where I am trying to get both. I want both, literal representation and the abstraction.

Ali Chetwynd: That leads on to my next question which has mainly to do with media. Gaddis is working with words. I guess with the J R play, you are using dialogue but also presence and action, and so on. Then, the rest of you are working with media that are non-verbal, or Tim’s at least making a very physical thing out of what was initially verbal. How do you think about this crossing between media? If Gaddis is an artist in words and all of you are doing something that is either straightforwardly non-verbal or maybe “verbal plus,” how does inspiration move across media? How much translation work do you have to do – in your head or with your hands – to make Gaddis make sense in your medium? How much of what’s there in the original language do you think actually does go, literally and directly, from your inspiration by Gaddis to your expression in your particular artwork? David Bird: I guess for me, there is a tone that comes through very clearly as it translates from the page to the music. That unhinged character is very prevalent in this piece and other pieces that have been inspired by Gaddis for me. I think the atmosphere is so strong, the technique is so powerful in Gaddis’s writing that it creates a kind of world-building mechanism to develop my own narratives and express myself with them. So, it feels like it has already moved into a space that becomes my own just in the way that it is written. It comes across so clearly and expressively that by the time they enter my head and my realm of expression, they enter my own creative playground and become very playful and easy to work with.

Edward Holland: Yes, I agree. There comes that moment where you flash on this idea, this concept and by the time you bring it in the studio, you have already added all these other things or you are bringing these other histories and ideas along with you. It all gets mashed together somehow and the art comes out of that. Conceptually, I do think about the pacing in Gaddis and the freneticism of his words and dialogue. I am more concerned, I think, with tempo when I am working, or the tempo in a work, as it relates to Gaddis. How to use the pacing between the painting’s elements to get the painting where I want it to go.

Ali Chetwynd: Yes. Then, for the FC Bergman people, how much of what ended up on stage was your invention beyond the dialogue? Did you give your actors very specific stage directions to do certain things or did you just give them Gaddis’s words and have them picking their actions up from there? How much of the physical embodiments of drama were you, as directors and productors, in control of? And how much was just the actors working with the words? Stef Aerts: Yes, we totally scripted it out of course in the scenario but also on the big scale model of the tower. So, every scene was totally prepared on this scale model with little puppets and little set pieces. Then, afterwards, because we were working with camera, we also had to make decoupage and preparation in camera. A lot of the physical work for the actors was already done. In part, because it was very expensive to have to work with fourteen actors. With this big amount of material, we did not have time to let the actors just fool around a little and search. No, it was really quite tight the way we rehearsed. We totally worked it out and said: “Ok, now you go there and then you wait for the camera to turn around. You say this word over there.” It was really very, very technical. It had to look very chaotic and it was also chaotic because, technically, in the tower there were technicians changing sets all the time. There were like forty people running up and down in the tower. It was one big chaos but it was really, really well orchestrated and very well prepared. So, there was not so much space for coincidence.

Thomas Verstraeten: I think that you are mostly talking about making the movie. So, that was actually one part. We had this very strict scenario for the movie. We also had a scenario for what was happening on the different floors while we were not filming there. Life just continued in all these apartments and all these spaces. The strange thing was that actually we, as a director’s team – because we were four people – we never saw the complete performance. We wrote the scenario for the visual part, the part that was not filmed. But we hoped that it would… For instance, there is a scene with Norman Angel and Stella in which something goes wrong and Norman got killed. We said to the actors: “Do something. Fight with each other and we will see how it goes.” So, we never saw it.

Stef Aerts: We tried. For a couple of days, I think, I was like running around the tower during the rehearsals to just try to get a grip on what we were making. It was just impossible because there was too much to look at. And then, of course, it was also our attempt. As a creator or as an artist, it was also quite frustrating. On a certain level, we really had to let it go because the beast we created was so enormous that it has, in a way, its own life and it began to lead its own life. It was quite special. What Thomas said is true. We never saw the complete form. It was also really strange because the performance was never ready. Every time you want to adapt some stuff or if you want to work on the light, you actually have to perform all the performance because it is like constantly moving literally. So, we were never able to finish it. So, it is quite interesting to see it. Every time we perform it, it is different in a way and we hope it is going in the best direction. It is a little out of our hands from now on.

Ali Chetwynd: Tim, how about you? How do you think about that kind of physical embodiment of words on a page versus Gaddis’s kind of linguistic and semantic way of communicating? Tim Youd: Well, I think, you know, I have… I am not just Gaddis. I mean I am retyping all these novels but, you know, in some ways, Gaddis’s enormousness, or whatever you want to call it, the comprehensiveness… That absurdity, the retyping of a 200-page novel is absurd. The retyping of a 950-page novel is really absurd. On some level, it helped me break through even further in my understanding of what I was doing and just the result of it. When you run the page through the typewriter that many times and you pound on it for months, you are going to get a much denser artefact. So, I think that those were happy results for me and it helped me… The longest thing I had retyped prior to that was All the King’s Men, Robert Penn Warren’s novel. I did that in Baton Rouge in the state Capitol actually, in the main room there. It took me, I think, twenty-three days. So, I was a little hesitant to commit… maybe I wasn’t. Not hesitant. But I was anxious. As I was committing, I was thinking: “Wow. This is could be a real grind.” It was not at all the case with J R, I loved that book. I think it is one of the greatest books I have ever read. And maybe the funniest book I have ever read. Probably the funniest book I have ever read. I am a little mixed on The Recognitions. I feel like there are parts of it… Just as a visual artist, I have some quibbles with how visual artists are discussed. But it was rewarding certainly just as an achievement. I retyped Leon Forrest’s Divine Days in the spring in Chicago. And that is even longer, namely 1135 pages. I think that in doing The Recognitions and J R back-to-back, it kind of helped me break through the 700-page barrier or whatever it was that was holding me back from doing a few more big ones.

Ali Chetwynd: Great. We’ve got just half an hour left. So, what I’ll do now is open up questions to everybody. If you artists have questions for each other, then you can just, I guess, put your hands up along with everybody else… Otherwise, let’s see if there are any questions in the audience. Also, anybody who is online, if you have any questions, you could either put your zoom symbol hand up, or you could write a question in the chat and then we will make sure to answer those as well. Audience Question: I have a question for Tim. Did you never think of yourself in relation to Borges’s “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote”? Tim Youd: Yes, sure, I mean, that has been asked of me before. I mean, the absurdist quality to it. I think, that underlines it. For me though, if we step away from the idea that, you know, everything about life is absurd, and just concentrate on what we are doing in the moment, I do take very seriously the act of reading and trying to be a good reader and become a better reader. And that really is what I see is my job when I am on one of these retypings, apart from creating these artefacts. The thing that preoccupies me the most is what am I getting out of this book. Hopefully, by the end of it, I will have an opinion on whether or not… Where do I stand? Where does this book stand in my estimation? Will I read it again? There are more books than we can ever read. So, each chance I get to sit down to read a book I want to get the most out of it and know that I may or may not be able to come back to it in my life, but at least I gave it my best effort.

Audience Question: I have a question for Edward. I was interested in the function of stars in your work. I am also writing a little bit about one of the scenes in which the stars are significant in The Recognitions. I guess I have a couple of questions. One, did you decide from the beginning that the zodiac would be part of the project? And what led you to integrate it? Did you do anything special for Capricorn because Gaddis was a Capricorn. Edward Holland: I have not done anything special for Capricorn other than every once in a while, I throw in a picture of Gaddis. I love the picture of Gaddis on the beach with a can of PBR in between his feet. It just cracks me up. So when I started the series, I like to do a lot of reading before I start a body of work, I read The Recognitions a couple of times. I took notes. Then I went through and I tried to read a lot of the books that Gaddis himself read in preparation for The Recognitions. That led me down to the world of The Golden Bough, The White Goddess and a number of more approachable esoteric, occult books. That put me down another path. The zodiac stuff started with Gaddis and then was informed by the books that he happened to have read around the time that he was writing The Recognitions. That pushed me further down the road. The stars stuff was reinforced by all of the talk of Mithras in The Recognitions, the sun worship and again that mythology that he, sort of, just places in there. For whatever reason that resonated with me the most. And so, that was sort of the point of departure initially.

Ali Chetwynd: Cool. Another audience question… Audience Question: I have a question for David. If I understood that right, part of the composition… Once you modified some of those MIDI files of the rag times as part of your composition… In the book Agapē Agape, the question of citation and plagiarism is important and you referenced that you had your own reflection on what role originality has to play. My question for you would be: what significance it has for you in this composition to work with this pre-recorded material? Then, of course, manipulating it to become a playing work for a listener. I didn’t pick out some of the sequences, and I would not have been able to take out whether that was you playing or whether it was a pre-recorded piece. I am interested in putting that side by side with Gaddis where citations can be made out if you know where to look. That is part of our jobs as critics, you know, to follow that path. From the point of view of somebody who created it, what relevance that citationality of originals has for you, where it matters what was your own take on it or the original as itself? But then, of course, it was worked on and there was presumably a lot in the original composition that was not taken? David Bird: That is a great question. I think with the way in which a lot of music is made now, with computers, there is a history and practice in sampling where, obviously, music is going to be based on other people’s sounds or music, but of course, you seek to make it your own. In that whole tradition, regardless of what genre you are working in, there is often a way of having a kind of inner textual conversation with the artist you are working with. But I think with the mindset that I was entering the piece with, in a sick way, I kind of wanted to just flatten everything, to let the dissonances between the pieces be structural elements that add tension, and to not have too many moments that would call attention to one piece or another. And I think part of that mirrors the certain nightmarish quality that Gaddis brings out in that novel, the kind of hopelessness that comes out of it; to reduce everything to a kind of flatness of expression. That was the one way I was thinking about it. I did not want any one piece to stand out over the other one. I kind of wanted all these notes to blend together or be textural as they lay on top of each other. Or to riff on one, like one would riff on something, like composing on a sampler or turntable. This made me reflect a lot on how I compose because, when you are working in a DAW (Digital Audio Workstation), you are taking chunks of sound and looping it. I have been a lot more aware of how I work with material since composing this piece. Also, I think, in the way that MIDI files are structured, you see the original notes that the composer intended rather than work with audio itself. So, it was kind of interesting to be like, “Ok, here I have this one song where I have this melody ascending upward”. And I could think of how to fill that out with another song. Hopefully, that answers your question a bit, but yes, ultimately I was thinking about flattening things and composing within an awareness of that, which was new and interesting to me at the time.

Audience Follow-up: Part of it for you… Part of the importance of working with that material, for you, elevated the consciousness of your own method. David Bird: Yes, I mean with that quote [from Agapē Agape], ‘every four-year-old with a computer.’ I kind of felt like that was attacking me, like all this computer music stuff is really easy to make… and sometimes it is, in a way. But I think in the way of working with these files you can get online, where it’s like a catalog and you can just choose random MIDI files and compose with them that way, there is a strange easiness in that. And I kind of wanted to see what the process of… “what if I compose in a really lazy way? What would come out?” And if that turned into anything, perhaps I could come back to it and do it in a more thoughtful way and see what comes out of that. So, it was a neat way of engaging with and sculpting material in music, in this strange digital space we work with now.

Audience Question: I have a question for FC Bergman. How did your actors take to Gaddis? Were there any stories to tell about their maybe not getting it in the way you got it, or something like that? In that same vein, I also was wondering if there were American references or American types that you did not recognize or immediately recognize these kinds of American voices. Or anything that happened with your building a play in that respect, as Europeans? Thomas Verstraeten: First of all, I think we had very, very wonderful and beautiful actors. Most of them were very motivated. For instance, the actor who played Edward Bast came to rehearsals every day with the book in his hands. He said: “No, no, no, no, but on page here and here Bast does this so you have to change it in another way.” He was almost too detailed for us. We had to do a lot of discussions with him. He was also a specialist after in rehearsals. It was really nice to work with such great and devoted actors. The actor who played Jack Gibbs also came everyday there with the book. He said: “I want to add this little sentence.” So, it was really nice. Of course, for the actors who were playing parts in the environment of the stock market, it was not always easy to understand what they had to say. It was some kind of a search together so that it would be understandable for everyone. It was important that the audience and the actors could understand what it was about. The second part of the question I actually forgot.

Audience Follow-up: The Americanness. Thomas Verstraeten: Yes, the Americanness.

Stef Aerts: Of course, the book is so “New-Yorkish” or so American and of course, we are Europeans. We can only try to understand as much as possible the little details and new answers in your marvelous culture. But of course, sometimes we would not get like the total pun of a joke. The book is so full of dialect and it is so nice. Even for a European, you can really understand and hear how different characters speak to each other and if they come from different backgrounds and neighborhoods. We were raised in Europe and we were raised with all the American movies. We saw a lot of them again and again. We saw lots of cinema especially for this project, New-York cinema of the 70s. I have the feeling that we had it more or less in our fingers, namely the feeling for Americana so to speak, but on a slightly naïve way.

Ali Chetwynd: Next we’ll have a question online. Audience Question: I am joining from Australia tonight. Thank you for having me. I am blown away by each and every work. I have a question for you Tim. Did you develop a relationship with the em dash? What was the label process of the em*dash? Did you have to say: “Type two keys”? Or was it one key on that particular typewriter? Could you just talk towards maybe that experience, other speech tags, different things for you now that you have written Gaddis? Thank you. Tim Youd: I tried to be literal. That is my whole approach to the thing. You know, I type with my fingers. I am not trying to be a good typist but I am trying to be as good at it as I can be. I don’t go back. I just pile on through it. I don’t leave any spaces between words unless I am doing poetry or a screenplay. But my approach is really just to keep going and to stay engaged with the book. I note-take heavily when I am doing it, some stopping to write on the book regularly and questioning it. Everything I type I have read beforehand which I think is—in my own estimation anyway—a precursor to good reading since you have to be working on it at least a second time through. You know, that is kind of the process. I don’t know if that is really an answer to your question but that is where I am coming from.

Ali Chetwynd: I have another question for FC Bergman. I think you said that the final thing was four and a half hours, is that right? Whereas I think the audiobook of the novel is 23 hours or something. How did you work out what to cut for what would work in four and a half hours? Were you cutting stuff because it wouldn’t work on stage? Or, were you cutting stuff because it was not your favourite bits of J R? What were the parts you were sad to lose? Stef Aerts: It was so painful to cut any scenes. I remember in particular the very funny couple; I think they are called the diCephalises. They were so funny but we just couldn’t find a place for them in our adaptation. It was such a pity to let them go because they are two of the funniest characters in the novel.

Thomas Verstraeten: In the decision process, we had to cut one thread. We felt immediately that we couldn’t do everything. So, we cut the school TV line more or less but also the teachers’ room and the discussions over there. So, we also had to cut Major Hyde which I thought was really a pity. So, we also cut all these characters that were connected to Vogel. We also cut all the characters that were connected to the school. We started in the school, in the beginning, with Edward Bast and his lessons that go completely wrong. We introduced Amy Joubert and Jack Gibbs but, then, we actually quit this plotline. It was also a pity that we had to diminish a lot the complete General Roll line. We stuck to short scenes. That was also very hard because I fell also in love with these characters. But, of course, if you want it to make it a bit doable, you have to make some choices.

Stef Aerts: In the beginning, we were for these choices, before this dilemma. Otherwise, we do the whole book and then it would take us probably, I don’t know, a performance of twenty-four hours or maybe longer. Or, we really want the audience to be sucked in it and therefore we can go maximum for four and a half hours. Otherwise, it becomes really too much and therefore we made a reduction of the book. After every performance, when we talked to the audience, we always said: “Please read the novel. Read it. It is a masterpiece!” Of course, if you want make a translation or an adaptation, you have to kill some darlings. In this case, a lot of them.

Ali Chetwynd: Great. Is there any other question? In that case, thanks so much to Edward Holland, David Bird, Tim Youd, Stef Aerts, Thomas Verstraeten.

Cite this essay

Chetwynd, Ali, Stef Aerts, David Bird, Edward Holland, Thomas Verstraeten and Tim Youd. "Gaddis Centenary Roundtable - Artists in Non-literary Media Inspired by Gaddis" Electronic Book Review, 8 March 2024, https://doi.org/10.7273/ebr-gadcent4-1