Including E-Literature in Mainstream Cultural Critique: The Case of Graphic Art by Khaled Al Jabri

In this essay, Doris Hambuch uses the image-based work of Arabic cartoonist Khaled Al Jabri to address concerns of technological dependence to reconsider our use of screens. Rather than simply reprimanding readers about the potentially negative dependence of our contemporary society on technology and its screens, Hambuch instead proposes that we look to Al Jabri's work as a way of reconsidering the role of the screen in visual poetics and graphic literature.

Electronic literature has grown as a field of studies globally during the past three to four decades, but mostly in rather exclusive circles of producers and/or critics. This paper aims to make a case for the inclusion of the comparatively new literary genre in general processes of literature creation and consumption. The Emirati graphic artist Khaled Al Jabri often depicts a rescue call for the print book in his cartoons. In many of his images, the print book appears as antidote to ailments engendered by exaggerated exposure to electronic media. None of the images introduces electronic versions of the revered book’s content. The following analysis of selected cartoons leads to the suggestion that electronic literature could present a welcome alternative to less useful preoccupation with screens if general audiences had greater awareness of and better access to it. I argue that none of the characters hooked to screens in Al Jabri’s cartoons indulge in electronic literature because this newer type of storytelling is still too compartmentalized. What the artist cherishes about the print book, creative stimulation for example, also distinguishes literature’s electronic manifestation from other kinds of screen entertainment.

Although many of Al Jabri’s cartoons appear in newspapers and magazines, they mainly reach their audience via the artist’s Facebook, Twitter account, Instagram album, and platforms such as the bilingual ‘creatopia’ (http://www.creatopia.ae/khaledaljaberi). These same venues, however, social media in particular, as well as the devices required for operation, often constitute the subject of Al Jabri’s critique of contemporary lifestyles. While he tackles a great variety of topics revolving around contemporary life in the United Arab Emirates and surrounding region, subtle criticism on negative effects of new technologies, and social media especially, appears as one of this work’s central themes. Many relevant cartoons mock the preoccupation with image exposure at the cost of traditional reading, the lack of critical thinking during social media consumption, the at times alarming influence of individual social media outlets, and finally psychological effects of our electronic era in general.

My analysis of selected cartoons identifies three major social aspects affected by the spread of electronic media. I call the first socio-psychological. This category includes images of children in danger of screen addiction. It further shows the effects of technology on people’s subconscious and their means of expression. I label the second aspect environmental, because it deals with potential threats to the natural non-human (or other-than-human) environment. Related to this category are images of required resources, of profit-driven manufacture, as well as of waste production. The third is the political-nostalgic aspect. It emphasizes the importance of traditional perspectives and provokes renewed respect for the print book as a remedy for the many ailments addressed in the preceding graphic stories.

A recurring cat figure with authorial presence clearly favors the paced lifestyle of the pre-electronic past over the virtual realities of the present. Since this cat is passionate about well-crafted stories and creative expression in print form, one would expect him to appreciate electronic versions of literature if he were to explore the genre. In the body of an animal, this authorial voice connects to the environmental aspect discussed in the second of the following three sections. If he were to embrace the fourth industrial revolution, he could qualify as representation of the so-called “posthuman.” In How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics (1999), N. Katherine Hayles elucidates the difference between scientific and literary texts (Hayles 1999, 24). She emphasizes that the latter “often reveal, as scientific work cannot, the complex cultural, social, and representational issue tied up with conceptual shifts and technological innovations.” Electronic literature obtains a privileged place to present such revelation because its practitioners combine skills from both realms, the cultural and technological. Al Jabri is himself such a practitioner. My ultimate argument is therefore that, given the chance, Al Jabri’s cat would advocate the informed reception of valuable electronic prose and poetry over anything his companions busy themselves with in the selected cartoons.

Socio-psychological aspects

Virtual reality has preoccupied the artist in his prose as well as in cartoons. Born in the late 1970s in Abu Dhabi, Al Jabri started to write short stories while studying for a Bachelor of Science in Mechanical Engineering at United Arab Emirates University. The title story of his first collection, published by the Abu Dhabi Authority for Culture and Heritage in 2010, is “Second Life.” The protagonist of this story struggles against an obsession with his avatar. One may imagine this protagonist chained to a screen like the young boy in Figure 1.

The snake-like appearance of the computer mouse in this cartoon titled “internet risks for children” represents the danger of addiction. The mouse cord literally ties the young boy along with his cat to a computer. Addiction is not the only negative side effect that accompanies the benefits of electronic media. Figure 2 shows its disturbing effects on the human subconscious through dreams. The cat, in this cartoon, sleeps peacefully on the bed of an older man whose dream reflects on the annoyance of YouTube advertising. The “You-Dream,” announced as “today’s dream” consists of the “ad break.”

The two people in these cartoons belong to different age groups. A young kid in Figure 1 and a bald, middle-aged man in Figure 2 illustrate the fact that the psychological dangers of exaggerated screen exposure, depending on content, can harm anyone regardless of age. The cat symbolizes a demand for caution in most of the images discussed during the following paragraphs. Figure 1 is an exception since the cat there shares his human companion’s bondage. Where the cat does serve as the wise observer who mocks our century’s obsession with and addiction to cutting-edge technology, this obsession’s implications on social interaction become even more pertinent. Where a cartoon ridicules people’s fascination with Facebook, Twitter (see Figure 11), Snapchat (see Figure 4), and the screens that facilitate these, the cat often poses as the more mature being whose wisdom offers warning signals for the other characters. One should not forget, though, that he represents an author whose art depends on technology and who takes part in the very mechanisms his iconic pet criticizes.

In “Digital Media, Anxiety, and Depression in Children,” Elizabeth Hoge, David Bickham, and Joanne Cantor address the dangers represented in Al Jabri’s cartoons and offer not only directions for much-needed future research, but also recommendations for educators, policymakers, and clinicians. Their specific topics are “anxiety and depression associated with technology-based negative social comparison, anxiety resulting from lack of emotion-regulation skills because of substituted digital media use, social anxiety from avoidance of social interaction […], and anxiety, depression, and suicide as the result of cyberbullying and related behavior” (Hoge/Bickham/Cantor 2017). With only few modifications, many of the studied conditions are not exclusive to children, but threaten adults in very similar ways. In his prologue to The Marvelous Clouds: Toward a Philosophy of Elemental Media (2015), John Durham Peters summarizes the impact of these conditions in more abstract terms when he states that ”… digital media intensify opportunities and troubles in person-to-person dealings” (Durham Peters 6). When he elaborates that the “meaning of a face, voice, or gesture cannot be captured in a thousand sentences,” he addresses an aspect of communication I return to in the context of language use. At this point, suffice it to emphasize that the virtual presence cannot equal the physical. Al Jabri’s cat, in a way, provides the missing company for the otherwise isolated screen-addicts in many of the selected cartoons.

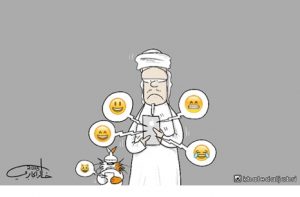

In most of the following cartoons, the artist portrays the cat as innocent bystander whose bewildered demeanor speaks to the silly or potentially dangerous nature of the human activities. The cat’s peaceful sleep in Figure 2 testifies to his sanity while the YouTube ad torments the human sleeper. A disturbed subconscious not only becomes evident in dreams but also in conscious means of expression. Speech bubbles in Al Jabri’s images frequently ridicule social media language, as seen in Figures 3 and 4.

These images address several of the anxieties and disturbances studied by Hoge, Bickham and Cantor. Although the majority of Emoji in Figure 3 are happy and imply laughter, the man sending or receiving them shows a tense and unhappy expression on his face. The man in Figure 4 is in shock about seeing the new baby as Snapchat icon, which must be the result of exaggerated Snapchat use. Such ailments would not derive from interaction with electronic literature. They are the result of exposure to digital content that pressures its users to compete for publicity and popularity, a competition that does not depend on verbal eloquence.

Communication via images may be quicker, unless one spends too much time with photo editing, but it lacks the cognitive challenges associated with verbal communication. Jane Z. Sojka and Joan L. Giese study these two variations of communication in “Communication through Pictures and Words: Understanding the Role of Affect and Cognition in Processing Visual and Verbal Information.” While this study’s context of marketing is less relevant for my argument, the general significance of affect and cognition for the reception of as well as participation in communication does apply to the combination of audiovisual and verbal elements in electronic literature. The 21st century’s obsession with images, favoring affect over cognition, does not bode well for processes involving verbal language.

In his witty comparative review of Emmy J. Favilla’s A World without ‘Whom’: The Essential Guide to Language in the BuzzFeed Age (2017) and Harold Evans’s Do I Make Myself Clear? Why Writing Well Matters (2017), Tom Rachman is meticulous in describing the two extremes on the spectrum of current linguistic variations. While Favilla’s account presents a trendy call for the ultimate linguistic laissez faire, Evans’ embodies the rigid opposite. The two contrasting views depart from contrasting credentials. The former’s experience as copy editor for Teen Vogue and the digital BuzzFeed engenders an embrace of linguistic lawlessness, “There is no hiding our collective incompetence anymore” (qtd. in Rachman, 2018, 8). Looking back at many years of experience as author of journalism manuals, editor of The Times, and contributor to The Guardian, Evans does not share Favilla’s enthusiasm for language use in the digital age. Instead, he wants to return to tedious labor on vocabulary and grammar rules. Rachman is keen to conclude his review of the two contrasting books with a proposed compromise. “Evans may err in his prescription,” Rachman writes, “but is correct to diagnose trouble” (Rachman 9). Rachman recognizes that the problem identified by Evans, general carelessness about language, reaches far beyond the obvious abundance of what used to be considered spelling and grammar mistakes. It connects to the fact that language is power, and “failure to master our tongues,” in Rachman’s words, “to allow others to direct them hither and thither – that is what Orwell was warning against” (Rachman 9). Where people do not cultivate their means of expression, they cannot recognize when powers-that-be abuse these, their language that is.

“The tyrant/is always afraid of the poet,” Zeina Hashem Beck writes in her celebrated collection Louder Than Hearts (Hashem Beck, 2017, 11). There is no doubt that this poet in question must be someone with a special talent as well as with the dedication to foster this talent through constant improvement of language skills, based on genuine love of verbal expression. The building of an extensive vocabulary, of the tools to match stylistic devices with content, depends on careful reception of equally commendable texts. Exclusive exposure to images and social media script cannot enhance eloquence, though Hashem Beck gives excellent examples of how the latter may find a creative way into great poetry. Different types of creative writing demand different registers, styles, and voices, but the linguistically better-equipped poet will always produce the better poetry. The same value statement applies to electronic literature, and its wider circulation would, one should hope, revive much-needed reverence for language. Electronic literature adds the audio-visual dimension that seems responsible for the addictive attraction of Al Jabri’s cartoon characters to their screens, to extraordinary use of language. If the cat’s various companions busied themselves with sophisticated texts on their screens, their capacity for the production and expression of urgent critical thinking would improve.

It is worth, at this point, to recall the diversity of “electronic literature.” Generally defined as literature created with electronic technology for digital reception, this genre may include texts as diverse as computer poems, multimedia installations, and video game narratives. In Electronic Literature: New Horizons for the Literary (2008), Hayles uses the word “shifty,” for example, with regard to “the demarcation between digital art and electronic literature” (Hayles, 2008, 12). She emphasizes that the newest field of literature “challenges us to rethink what literature, and the literary, can do and be” (Hayles 42). This challenge may prompt critics to focus on the technical aspects of e-texts, or to recognize literary qualities in entertainment, as Astrid Ensslin does in her studies of video game narratives. Ensslin’s concept of the “ludic-literary continuum” (Ensslin/Rustad/Bell, 2013, 76) once again highlights the interdisciplinary and hybrid nature of recent storytelling. In the broadest sense, Al Jabri’s cartoons themselves could count as electronic storytelling, though they lack audio as well as interactivity.

The thought to approach these cartoons as electronic literature, relies on one’s acceptance of cartoons as any kind of literature. Aaron Meskin tackles this question with much insight in “Comics as Literature?” (2009). He provides a thorough overview of opinions regarding the inclusion of comics in the literature category, and much of his argument is equally relevant for cartoons. Meskin’s opening, that “not all comics are art,” (Meskin, 2009, 219), parallels the present argument’s assumption that not all writing is literature. Granting gift, skill and intent, however, and with an emphasis on their hybrid nature, it is easy to agree with Meskin’s conclusion that “we appropriately appreciate the literary aspects of a comic book (when they are present) in light of the norms and styles and concerns that attach to literature” (Meskin 239). This realization is relevant for a justification of certain critical approaches. The hybrid nature of art forms, such as comics, cartoons, films, or multimedia installations ideally appeals to what Eman Younis calls a “hypercritic” in her interview with electronicliteraturereview (2017). A study of such hybrid genres becomes more useful the more information a critic has about their technical, audio-visual, or performative dimensions. Such studies therefore also lend themselves to interdisciplinary collaborations.

To consider Al Jabri’s art itself as part of the genre of electronic literature enforces the suggestion that it should include references to this genre. Such references could even be self-reflexive. They would add positive connotations to the theme of screen exposure. They would propose alternative judgment of media content, and the portrayed characters would respond to stimulating stories and ideas rather than to haunting, meaningless icons. The characters would appear less self-centered and more in touch with their immediate environment. The latter includes the other-than-human environment, which is the subject of the following section. If a parent is obsessed with Snapchat documentation, as in Figure 4, she or he cannot simultaneously focus on the physical object of this documentation. Likewise, when a photograph or video separates the person behind the camera from a landscape, this person will less likely focus on her or his own inclusion in the latter. The cartoons studied in the following section identify environmental dangers related to electronic media.

Environmental aspects

The concerns in the preceding section revolve around effects of our electronic age on the individual. This section turns to the individual’s natural environment, the planet’s resources and sustainability. Four selected cartoons address the problems related to required energy resources, the impact of profit-driven, capitalist production dynamics, and the resulting need for waste removal. Figure 5 suggests that the machine or its technology actually has control over the human, rather than the other way around. The device appears personified and functions as the only animate being in the scenario, in which the human-looking creature resembles an electronic puppet, and the cat’s batteries are charging via the tail. The power is here with the electronic device, depending on all that is required for its production and operation. A human being’s dependence on energy and Wi-Fi, likewise, is the theme in Figure 6. The man’s thought bubble reads, “No Wi-Fi?” The cat, much more down to earth, thinks of truly existential matters such as his next meal. The deserted island further symbolizes the physical isolation a virtual world can create.

Figure 6 is the first cartoon with an explicit outdoor setting. In Figure 3, the setting is irrelevant, but all the other previous scenes take place indoors. The boy in Figure 1 might be in his own room, the sleeper in Figure 2 in his bedroom, and the family in Figure 4 is in the hospital, as identified by the signs on wall and crib. Urbanization already moved much human activity from outdoor into indoor spaces, such as offices, shopping centers, gyms. One may speculate that the spread of electronic media has added to this trend. Moreover, when people are active outdoors, their tendency to document this activity via devices alters the experience of the natural environment. Often enough, phone calls or texts distract a person outdoors from paying close attention to her or his surroundings. As a result, not everyone may notice a landscape’s pollution, for example, where it is visible. The following two cartoons revolve around less visible pollution.

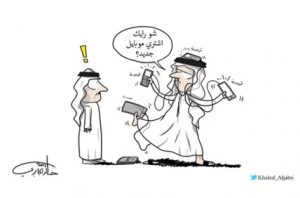

Figure 7 shows obsession with the latest Smartphone models, as well as a certain immodesty of individuals who cannot get enough of them. The hyperactive juggler on the right is asking, “Which new mobile should I buy?” All four devices he is holding are ringing simultaneously, and the silent, puzzled observer takes the place of the cat, who is absent from this image. The cat is also almost invisible in Figure 8, where only tail and ears are showing from underneath a heap of discarded mobile phones. Since the newest models are the result of fierce competition, their production is too fast, and their duration too short. Following profit-driven mechanisms, each company aims to sell more than another does. In order to sell more, each company needs to produce more, as well as convince buyers that its new models are best. Each company thus contributes to the increasing problem of electronic waste. The man reading the paper in Figure 8 expresses disbelief in reaction to statistics showing roughly 15-million smartphone subscribers in the UAE. The man may be genuinely surprised at the number, but he may also represent the typical denier of threats to the other-than-human environment.

“Electronic waste, or e-waste, is an emerging problem as well as a business opportunity of increasing significance…,” Rolf Widmer and his team write in their 2005 essay “Global Perspectives on E-Waste.” Widmer’s research group estimates about 500 million dumped PCs between 1994 and 2003 and emphasize that PCs account only for “a fraction of all e-waste.” In their foreword to the more recent Global E-Waste Monitor – 2017, C. P. Baldé and his team write that, “the amounts of e-waste continue to grow, while too little is recycled.” E-waste, in short, poses the newest addition to the persistent hazardous waste problem, and the achievement to eliminate paper production for print media has really only led to a different kind of threat to the planet’s sustainability.

Guided by maritime metaphors, The Marvelous Clouds aims to reconsider media theory in light of the traditional meaning of media as the natural elements (Durham Peters, 2015, 2). The proposition that “if media are vehicles that carry and communicate meaning, then media theory needs to take nature, the background to all possible meaning, seriously,” resonates in the present discussion of environmental concerns. Many eco-critics, however, might go further by thinking of nature less in the back- and instead in the foreground. Nature-consciousness should indeed guide considerations of meaning and their negotiation, to avoid the kind of dystopia painted in Figure 12. In light of the preceding section, one can imagine that screen addiction takes part in the neglect of the other-than-human environment. Much activity involving screens takes place indoors. Outdoors, it prevents an individual’s understanding of her- or himself as part of a natural landscape. In Al Jabri’s art, the phenomenon of the selfie further explores this disconnect between human and other-than-human nature.

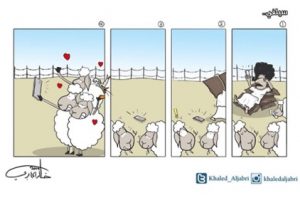

The tremendous popularity of the selfie has produced studies, which trace its origin and distinguish in detail between user groups and occasions. The most prominent book-length study in English is Alicia Eler’s The Selfie-Generation: How Our Self Images Are Changing Our Notions of Privacy, Sex, Consent, and Culture (2017). While this study explains many less obvious purposes of the selfie, it fails to place the phenomenon in the context of environmental concerns. Often, the selfie does relate to the urge to appear popular, successful, and attractive online. It thus shifts focus from any surroundings to the self within an environment. Al Jabri criticizes this function of the selfie in Figure 9. In this cartoon, the cat joins a group of sheep in imitating the strange and conceited indulgence in one’s own image the man in the first of four cartoon parts captures. It is significant to notice that the sheep form a group and even invite the cat, while the human poses as isolated narcissist. Often, selfies are of course about groups, but the other-than-human element always remains in the background, as it cannot operate the device. In Figure 10, Al Jabri imagines a scenario in which this does happen. This cartoon personifies the planet Earth and moves the camera into the universe.

Figure 10, in which Earth uses a selfie stick, establishes an explicit connection to the environmental concern at hand. It signals how widespread the selfie phenomenon has become on the one hand, and how insignificant the human self remains within a cosmic context. The man, who sees himself in the center of his own documentation in Figure 9, remains unidentified on the planet as well as in its selfie reproduction in Figure 10.

The transformation a poser’s actual image may receive during the selfie distribution is of particular importance with regard to the preference of virtual over face-to-face communication. As Durham Peters points out, text messaging and social media interaction not only stall time, they also suspend “the risk of real time” (Durham Peters, 2015, 273). “People prefer being telepresent via Facebook, Twitter, and text messaging,” Durham Peters writes, “not because the software provides the ‘feeling’ of ‘sitting face to face,’ but rather because it doesn’t provide it at all” (274). In many cases, it allows for the enhancement of an image. This quality, no doubt, accounts for some of the addictive potential of screen interaction. The personified Earth in Figure 10 could indeed present an image in the selfie taken, which eliminates e-waste and all other kinds of pollution that threaten the planet’s sustainability in its actual presence.

Figure 11 develops the concept of waste further, moving from literal waste of disposed devices to metaphorical waste of time and energy with too much useless or even harmful information retrieved via social media outlets. Twitter serves here as the example of a medium that contains more junk than gems. The cat, it seems, is trying to escape the pile of news garbage. The quality of news has of course always varied, but electronic distribution has accelerated the impact of trivial, distorted, unfounded, and misleading information, as the new technologies have accelerated activity in general, for better and for worse. Much speculative fiction has painted dystopian futures based on imaginary continuation of certain trends, including an ever heightened pace. Disregard for environmental concerns feature prominently in such futures. Figure 12 depicts Al Jabri’s speculative dystopia in the year 2050.

According to this projection, in only three decades, “kind people have disappeared.” This is the thoughts in the smaller thought bubble. With runny eyes, the barcode on his chin and a serial number on his forehead, the thinker looks more like a zombie-robot than a human being. In the context of preceding cartoons, one can easily understand this creature as victim of all discussed ailments combined, and social media had its distinct share in the process, as the well-known symbols in the bigger thought bubble show. The cat is once more missing altogether from this picture. The authorial presence would rather not take part in the horror of this scenario. It expresses a typical burnout in the aftermath of too many simultaneous pressures. In The Slow Professor: Challenging the Culture of Speed in the Academy (2017), Maggie Berg and Barbara K. Seeber address mechanisms that may lead to such burnout in the university setting. Al Jabri’s cat, when visible, signals the wisdom that slowing down in general, not only in the academy, would benefit today’s globalized societies. This sentiment is most prominent in scenarios that glorify the past, as well as those that demand renewed respect for the print book, presented as a treasure that symbolizes pre-fourth industrial revolution leisure. The following section looks at samples of respective cartoons.

Political-nostalgic aspects

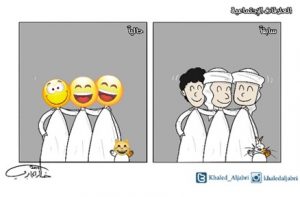

The preceding two sections revolve around potential dangers of the 21st century electronic age. These dangers include the negative effects of new technologies and their achievements on individuals, and they include environmental threats, such as resource requirements and e-waste. Seen from such a skeptical point of view, the slower-paced, more genuine nature of social relations in the past receives a new appeal. In Figure 15, genuine friends on the right, the side identified as “the past,” have turned into Emoji creatures in “the present day.” In the comparison, the Emoji icons resemble masks.

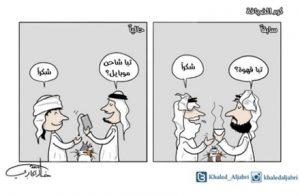

Figure 13 juxtaposes a shared cup of coffee in the past with today’s treat of a mobile phone. The cat’s head is bandaged in the image of the current time, signaling that the device stands symbolic for much of the rat race (to employ a cat-related metaphor) of today’s lifestyle. It also comments on the loss of modesty with regard to the material value of presents. In “Information and Expression in a Digital Age: Modeling Internet Effects on Civic Participation,” Dhavan V. Shah, Jaeho Cho, William P. Eveland, Jr., and Nojin Kwak discuss research dedicated to the socio-political dangers the current lifestyle implies. Their discussion confirms many of the points made in the preceding sections. They are referring also to other studies on the decline of face-to-face socialization, the potential for addiction and cyberbullying, as well as the virtual distortion of reality. Unlike the studies cited, however, Shah and his team criticize that most of the respective research focuses on the amount of screen exposure rather than on the distinct patterns of use. The studies Shah and his team call for, which should pursue cross-cultural, cross-continental collaborations, might help evaluate preferable digital content. They might detract from a glorification of the past and speak to ways in which values from the past could gain renewed respect within modernized scenarios. One may speculate that the awareness of electronic literature could play an important role in this process.

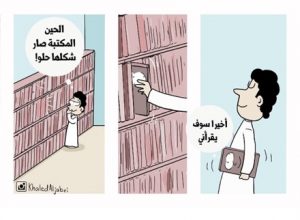

In the context of Al Jabri’s graphic art, if more tech users were reading original e-literature rather than the kinds of screen entertainment referred to in the analyzed cartoons, the cat would thrive with them. Their screens could then have the same stimulating impact that the print book is associated with in the remaining four cartoons. The personified print book in Figure 15 is throwing a safety ring to someone drowning in an electronic device.

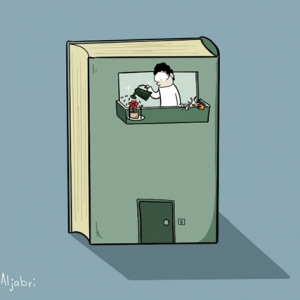

In Figure 16, the print book provides a home for the caring person, who cultivates it like a garden. The book itself provides this garden in the shape of a tiny balcony. If one were to evoke Voltaire’s Candide (1759), this association would stress the importance of the local, as well as of the other-than-human environment that is the subject of the preceding section. Candide’s suggestion, “but let us cultivate our garden,” comes as reply to the realization that all the journeys and events of the philosophical novel have brought him to the time and place he finds himself in at the story’s conclusion. The subtitle of the French original identifies optimism, in response to 18th century European philosophy, as responsible for the satirical tone of Voltaire’s classic. The print book’s function in the cartoons of this section, likewise, adds an optimistic angle to the discomfort preceding cartoons express in light of current lifestyles. To recognize the importance of the local, despite decades of globalization, also requires an individual to focus on the immediate environment, human as well as other-than-human. Such focus may lead to the appreciation of a tangible library, such as the one depicted in Figure 18.

It would lead the woman in Figure 17 to sit down in the actual world (maybe a garden) and read her book, rather than pretend to do so in her virtual world. As she posts, “I sip my warm coffee and enjoy reading this fascinating novel,” she dumps the novel in the trashcan. The cat, in contrast, guards a pile of three books in the same room. Al Jabri thus criticizes the superficial nature of much social media interaction. The print book appears as his only alternative to the ridiculed screen activities, when references to valuable electronic literature, even gaming narratives could serve a similar purpose.

Experts in electronic literature are well aware of the compartmentalization of their subject of study. The Electronic Literature Organization (ELO) has therefore introduced a special initiative. The Preservation, Archiving and Dissemination Initiative (PAD) has produced, for example, a special collection that can help teachers with respective study plans (Hayles, 2008, 40). The classroom is a crucial venue to familiarize general readers with a new genre. It may be a while before electronic literature receives a presence at book fairs, within general literary scholarship, let alone in sites of so-called “popular” culture, such as cartoons.

The production of e-lit requires technologies responsible for undeniable hazards unique to today’s information and gadget age. As represented in Al Jabri’s graphic art, these hazards relate to socio-psychological, environmental, as well as political-nostalgic aspects of globalized societies. Al Jabri inserts his authorial, cautioning presence in the shape of an iconic cat figure in most of his images. This cat worries about screen addiction and other psychological dangers of his companions. He warns about the power electronic devices may have over their owners, as well as about the negative impact they have on our natural environment. He often presents the pre-electronic past as desirable contrast, and the print-book as preferable over electronic media consumption. If any of the cartoons, however, portrayed the cat’s exposure to commendable e-literature, even self-reflexive content, this cat’s assessment of new technologies would arguably appear a lot more positive than it does in the selected cartoons. He would then not only highlight benefits of the creative possibilities engendered by the digital age, but he would also acknowledge his own participation in and contribution to them.

References

Al Jabri, K. (2010). الحية الثانية. Abu Dhabi Authority for Culture and Heritage.

----------. (2010). Second Life. Trans. Marei Grundhöfer. Lisan.

Baldé, C. P.; Forti, V.; Gray, V.; Kuehr, R.; Stegmann, P. (2017). The Global E-Waste Monitor –2017. United Nations University.

Berg, M.; Seeber, B. K. (2016). The Slow Professor: Challenging the Culture of Speed in the Academy. The University of Toronto Press.

Durham Peters, J. (2015). The Marvelous Clouds: Toward a Philosophy of Elemental Media. The University of Chicago Press.

Eler, A. (2017). *The Selfie-Generation: How Our Self Images Are Changing Our Notions of Privacy,*Sex, Consent, and Culture_. Skyhorse Publishing.

Ensslin, A.; Rustad, H.; Bell, A. (2013). Analyzing Digital Fiction. Rutledge.

Hashem Beck, Z. (2017). Louder Than Hearts. Bauhan.

Hayles, N. K. (2008). Electronic Literature: New Horizons for the Literary. University of Notre Dame Press.

---------- (1999). How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, andInformatics_. The University of Chicago Press.

Hoge, E.; Bickham, D.; Cantor, J. (2017). “Digital Media, Anxiety, and Depression in Children,“Pediatrics 140.2, pp. 76-80.

Meskin, A. (2009). “Comics as Literature?” British Journal of Aesthetics 49.3, pp. 219-239.

Rachman, T. (2018). “Writers Gonna Write.” The Times Literary Supplement, Jan. 16, pp. 8-9.

Shah, D. V.; Cho, J.; Eveland, W. P., Jr.; Kwak, N. (2005). “Information and Expression in a Digital Age: Modeling Internet Effects on Civic Participation,” Communication Research 32.5, pp. 531-565.

Sojka, J. Z.; Giese, J. L. (2006). “Pictures and Words: Understanding the Role of Affect and Cognition in Processing Visual and Verbal Information.” Psychology and Marketing 23.12, pp. 995-1014.

Voltaire, F.-M. (1918 [1759]). Candide. Accessed on 20 Jan 2018 at https://www.gutenberg.org/files/19942/19942-h/19942-h.htm

Widmer, R.; Oswald-Krapf, H.; Sinha-Khetriwal, D.; Schnellmann, M.; Böni, H. (2005). “Global Perspectives on E-Waste.” Environmental Impact Assessment Review 25, pp. 436-458.

Younis, E. (2017). “Interview with Eman Younis.” Electronicliteraturereview Accessed on 18 Jan 2018 at https://electronicliteraturereview.wordpress.com/2017/10/20/interview-with-eman-younis/

Cite this article

Hambuch, Doris. "Including E-Literature in Mainstream Cultural Critique: The Case of Graphic Art by Khaled Al Jabri" Electronic Book Review, 2 December 2018, https://doi.org/10.7273/h6de-yd69