David Ting excavates the archived compositional history of Agapē Agape to test what we can learn from the marginal annotations in Gaddis’s working library, focusing on his copy of Susan Stebbing’s Philosophy and the Physicists. Ting finds Gaddis testing his own ideas against those of Stebbing and her sources, while making outward connections between this technical material and his literary reading in Plato and Faust. Illuminating the novel’s chronological evolution, Ting also provides us a case study in tracking how authors use their reading as a “means of invention.”

Various materials from the Gaddis Archive by William Gaddis, Copyright © 2024 The Estate of William Gaddis, used by permission of the Wylie Literary Agency (UK) Limited.

Due to the copyrighted archival material reproduced here, this article is published under a stricter version of open access than the usual Electronic Book Review article: a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 license. All reproductions of material published here must be cited; no part of the article or its quoted material may be reproduced for commercial purposes; and the materials may not be repurposed and recombined with other material except in direct academic citation – https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ .

A key benefit of an archive-based study of any author is the opportunity to forensically reconstruct the life of their mind. A catalogue of identified references and allusions identified in their published work can be fruitfully open-ended. But scholarly precision is aided by engaging with the archive of the author’s own reading: the “why” behind someone’s choice to read a book, and the dynamic, attentive “how” of that reading as evidenced by the annotations they make. The present study is in essence a partial intellectual biography, constructed from the evidence left behind in one notable man’s books, notes, and library. Although long, quiet gaps appear to separate the publication dates of William Gaddis’s few, ambitious published works, my objective is to suggest that an intellectual’s most important contributions may not solely be in their finished creative products, but in their process of attention.

Gaddis’s personal library is a remarkable record and portrait of his mind at work. Recent scholarship has drawn increasingly on his Papers at Washington University in St. Louis, but the personal library, and the annotations within it, have seldom been addressed. Alongside the archive’s meticulously catalogued boxes of drafts, notes, and personal effects, the personal library’s trove of books that Gaddis annotated is a rich parallel biography, deserving further study and exploration. As both a writer with serious formal concerns, and a voracious reader aiming to distill the chaos and paradoxes of his surroundings into further creative texts, it should come as little surprise that Gaddis often read with a pencil in hand, annotating with an impressively honed readerly intellect.

Over 1,200 volumes are catalogued in the Gaddis Working Library. Roughly 240 individual books bear the physical traces of his reading. Notes in pencil and jottings in pen are common; newspaper clippings he found relevant, or scraps of paper bearing reminders of daily tasks are occasionally wedged in his books. Although the boxes of the Gaddis Papers are now held separately from his library, the materials were intermixed during his literary life: drafts for his published and unpublished work, and typewritten bibliographies for personal research projects found in the Gaddis Papers allude to titles in his collection, and to others borrowed from libraries and colleagues. Gaddis was a novelist, and a studious researcher. His habit of producing typewritten monographs on his reading began before he started The Recognitions (1955),1The first example this researcher encountered in the archives was the “Reading notes, circa 1947-1948” folder, located in Box 21, Folder 7. and persisted until the end of his life, through the drafts of his posthumously published novel, Agapē Agape (2002).

For five decades, Gaddis kept up an intertextual conversation of astounding intensity between his notes, drafts, and personal library. The breadth and depth of his reading, knowledge, and ideas are altogether overwhelming—yet he employed consistent work habits and methods of organization to enrich his thinking and writing. Perhaps his trademark creative habit was the harmonization of past and present materials: in a single folder, a scholar might find oxidized pages slipped in next to notes made on yellow legal pads and white A4 printer paper: each the record of a different era. But such separate notes show what conclusions crystallized after Gaddis had time to ruminate on his reading. In no other form are Gaddis’s powers of insight so immediately displayed as through the in-text annotations he left as a creative reader of his personal library. I’ll show how notes in just one of his books illuminate the connection between his first and last novels, especially in their concern with one of his career’s major concerns: living under the threat of determinism.

The Agapē Connection

The essential paradox of Gaddis’s literary life is that the project he was most intensely dedicated to, and for the longest period, nearly failed to see publication. Annotations toward it reveal the potency of Gaddis’s creative reading methods, as propelled by an extraordinary obsession.

For fifty years, Gaddis toiled. Undergoing multiple transformations of title and genre, expanding and contracting in length, taking up hundreds of pages of notes, the “player project” (for decades referred to as “PP” in his materials, and likely given the tentative title of Agapē Agape for the first time in the mid-1950s)2The title emerged among the materials for an unfinished Gaddis project entitled Sensation, dating from 1955-56. See the entry on Sensation in Ali Chetwynd and Joel Minor’s guide to Gaddis’s unpublished fiction elsewhere in this special journal issue. was the culmination of his lifelong attempt to capture the crisis of creativity and the arts in America. The intertextuality of this strange late volume has been studied and chronicled by the likes of Steven Moore and Joseph Tabbi, with numerous scholars examining its Gaddis-acknowledged literary debt to Thomas Bernhard.3For the fullest recent analysis of this influence, see Klebes. The unpublished material that was eventually transformed into the posthumous text, though, is akin to geological strata: each era of work differing in creative circumstances and content. While some concepts remained roughly the same throughout the project’s evolution, others changed dramatically—and the reasons for these alterations can be located and tracked through close forensic attention to the documents in the archive, and their metamorphosis toward the final publication.

Gaddis began working on Agapē Agape as early as the 1940s. Its first form was an essayistic allegory on mechanization in the arts, which he hoped to submit to the “Onward & Upward With the Arts” column of The New Yorker. Although his New Yorker submission was rejected, a different version was published by The Atlantic in 1951, as “Stop Player. Joke No. 4.” In the first paragraph of that Atlantic column, Gaddis captured an American creative crisis that the automated music-making of player pianos represented for him: “… the player offered an answer to some of America’s most persistent wants: the opportunity to participate in something which asked little understanding; the pleasure of creating without work, practice, or the taking of time; and the manifestation of talent where there was none” (“Stop Player” 92).

Gaddis’s lifelong war against creative fakery in the arts is perfectly encapsulated in that sentence alone. But he does not seem to have believed that his point had sufficiently hit home. Over the next four decades, his devotion to this message was unceasing, growing continually in intensity. Through the fifty-year gestation of the player piano project, Gaddis would accumulate dozens of books related to the subject, consuming countless newspaper articles on the relation between technology and the arts, writing and rewriting his player piano essay ad infinitum. He received a contract to write a book on the topic at the same time as for J R in the early 1960s, and appears to have drafted a long essay version around this time, which was never completed. The unfinishable project even made cameos in both The Recognitions (1955) and J R (1975).

Literary scholarship tends to date the resolution of this creative turmoil to Gaddis’s literary encounter with Thomas Bernhard’s novels in the 1990s, as recommended to him by the legendary New Yorker cartoonist, Saul Steinberg. Gaddis saw, in Bernhard, a kindred spirit. He had reputedly read all of Bernhard’s work then translated into English. Calculated plagiarisms from Bernhard’s novels (especially The Loser) strongly inform the narrative of the final version of Agapē Agape—which, fifty years on from its inception, emerged almost from the author’s deathbed not as a magazine column, nor a historical study, but as a highly condensed metafictional novella.

Gaddis did not work continually on this project. Periods of stops and starts mark his progress. The reading material that he consumed continually reinvigorated his belief in this long-term endeavor. By focusing on the annotations to just one book from his personal library, which he read in the years shortly after the dismaying reception of his first novel, I will aim to capture Gaddis’s thought in the process of his testing his project’s tenets.

Stebbing

In the five long decades of the player piano project’s gestation, Gaddis relentlessly assimilated reading material that could sharpen his mind, his philosophy, his clarion call about creativity under fire. We continually find him “testing” ideas against the work of other authors during his writing process. “Testing” is one of four approaches that (in a fuller unpublished project on the methods of reading by which Gaddis developed Agapē Agape) I find Gaddis taking to his source material. The other methods include “building” (exemplified in his annotations to Aristotle’s Politics), “framing” (in his annotations to Muriel Rukeyser’s biography of Willard Gibbs), and “stealing” (on his late relationship with his “plagiary” Thomas Bernhard). Gaddis’s interest in all these sources has been documented elsewhere,4See Moore, for example. but here I address another method—“testing”—in relation to an equally significant, densely annotated, but yet-unrecognised source from Gaddis’s 1950s reading:

Philosophy and the Physicists (1937), by the British philosopher L. Susan Stebbing.

While Stebbing’s book dates to the 1930s, Gaddis owned and annotated a Dover mass-market paperback edition from 1958. Reaching Gaddis through this republication a mere three years after The Recognitions was released, Philosophy and the Physicists is remarkable for its thematic overlap with his first two novels, as well as his annotations making clear its contribution to his lifelong study of the player piano. Gaddis, detecting the resonances with what he’d already published, and establishing further connections with his works-in-progress, uses Stebbing’s book as an opportunity to test his published work’s durability, while seeking to reinforce the intellectual framework of his future projects.

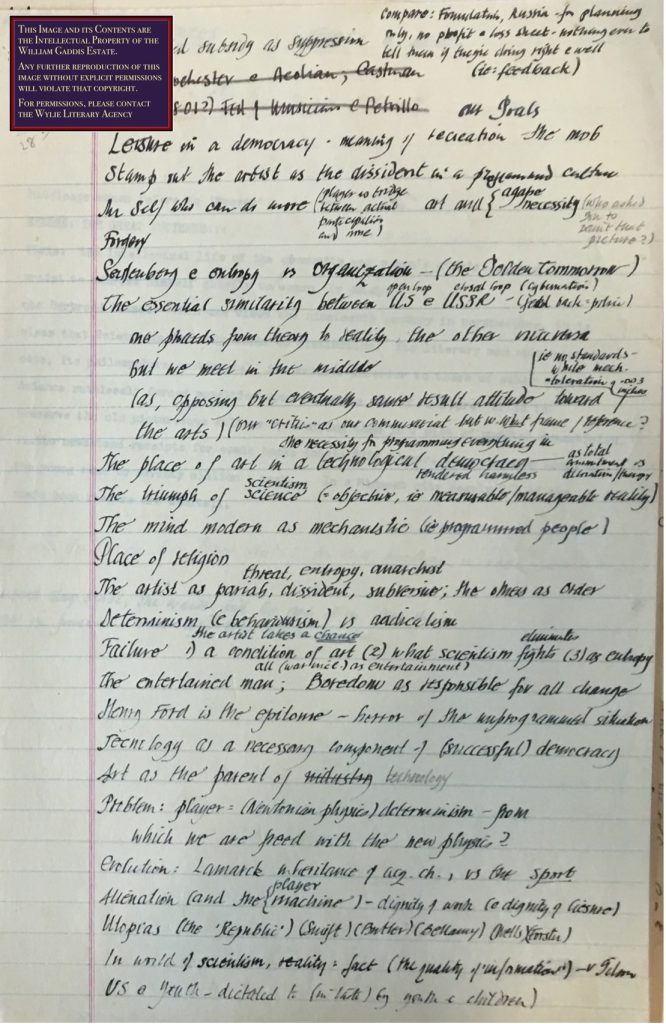

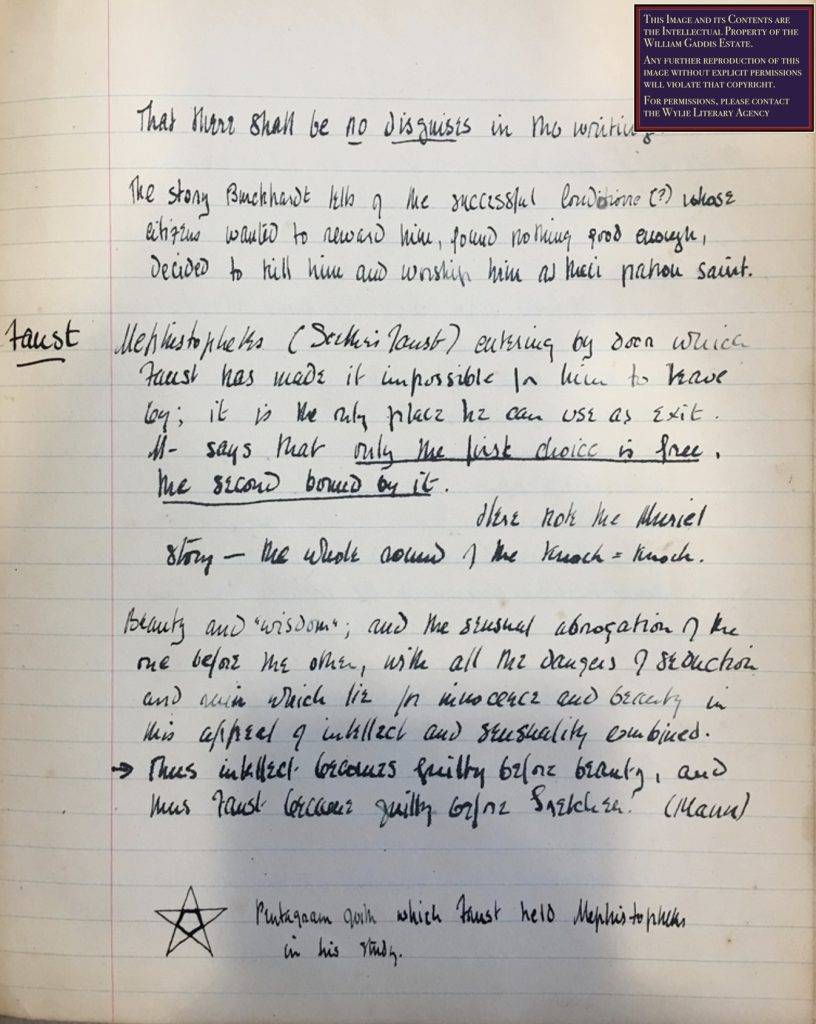

Gaddis’s annotations are evidence of his writerly attention to what he read, and his separate working notes are often where these concerns are centralized. List-making, in these working notes, was an essential part of Gaddis’s workflow: hundreds of such sheets reside in his archive. Our most representative roadmap for Gaddis’s intellectual concerns in the late 1950s, pertaining to Stebbing and the PP, might well be the following page, composed in a fine calligraphic hand, from a folder of loose 1950s notes toward the player project (see Figure 1).5Dating the materials was helped tremendously by the Finding Aid, as organized in the summer of 2016, when I undertook my research in the William Gaddis Collection. Dates are also roughly suggested by the type of paper used, and the quality of Gaddis’s handwriting.

This document is exceptional for our study: it presents a host of critical themes whose ambitions exceed even the contents of the eventual 1960s draft essay version of “Agapē Agape: The Secret History of the Player Piano.” Hardly a single author’s name is spelled out on this sheet. But the influence of Gaddis’s library is deeply pervasive: the annotations in Stebbing’s Philosophy and the Physicists not only match key phrases and themes listed here, but question, push, and dispute them, revealing how Gaddis’s annotated reading functioned both as a prompt to new ideas, and as a testing arena where he could hone his own ideas against their articulation by others.

This paper subsequently examines how Philosophy and the Physicists is used to test the validity of five lines from that page of notes:

- “The triumph of scientism/science (=objective, ie measurable/manageable reality)”

- “The mind modern as mechanistic (ie programmed people)”

- “Determinism (e behaviorism) vs radicalism”

- “Problem: player = (Newtonian physics) determinism – from which we are freed with the new physics?”

- “Alienation (and the player/machine) – dignity of work (e dignity of liesure) [sic].”

I devote a section of the paper to Gaddis’s annotated engagement with each of these topics in Stebbing, followed by a conclusion. Gaddis uses Stebbing’s book as a dynamic testing ground, as a soundboard for his ideas. His tactile engagement with the book shows how he conceived his working notes and his other volumes as active components in a sprawling circuitry.

Stebbing’s study, strongly echoing major themes Gaddis had already explored in The Recognitions, analyzes how determinism and relativism have been written about in non-technical terms—how they have been transposed into allegories and metaphors for processing daily life in the twentieth century.6Gaddis was interested in the shifts between scientific movements, whether the text was a history of science study, or a novel. See the faint vertical line drawn next to this passage in his copy of War and Peace: “Ever since the law of Copernicus was discovered and proved, the mere recognition that not the sun, but the earth moves, has destroyed the whole cosmography of the ancients. By disproving the law, it might have been possible to retain the old conception of the movements of the heavenly bodies; but without disproving it, it would seem to be impossible to continue studying the Ptolemaic worlds” (Tolstoy 1144). For each of the lines above, Gaddis weighs his ideas about determinacy and indeterminacy against Stebbing’s study, while also occasioning new routes. In the margins, he establishes new contexts for Stebbing’s findings, linking her passages to external texts as diverse as Norbert Wiener’s Cybernetics, and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Faust. My comparative, intertextual methodology in what follows can be a helpful tool for making sense of the William Gaddis Papers at large. The careful exercise of drawing connections between his personal library and his working notes shows how the vigilant cross-examination of different elements in the manuscript collection can reveal what volumes Gaddis was actively reading at a particular time, even if book lists are unavailable, or titles unreferenced.

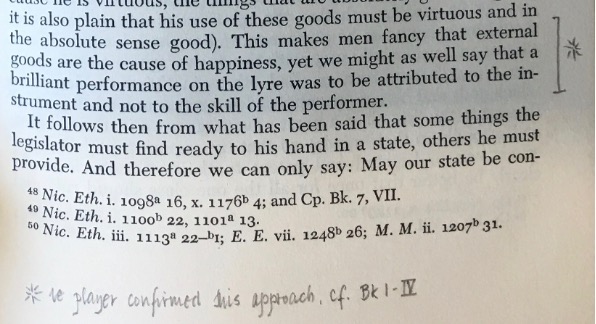

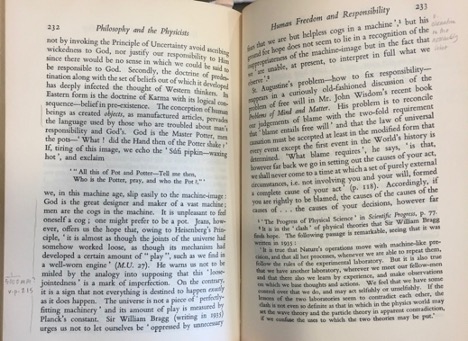

Before those analyses commence, a word on the types of annotations in Stebbing’s book: the vertical lines that Gaddis uses in Philosophy and the Physicists to mark important passages are unusually long. Researchers embarking on any study of his personal library should expect to encounter slightly different internal visual systems of annotations in each book, almost as if Gaddis were conducting an organic, one-on-one conversation with each author. In his copy of Aristotle’s Politics Gaddis uses a more complex system of pictographs—triangles and hangman brackets—to mark and categorize critical quotations.7See the Gaddis copy of Politics for these characteristic brackets, with several example page numbers: 7, 123, 194. He then reproduces these quotations almost verbatim in his 1960s essay “Agapē Agape: The Secret History of the Player Piano.” An example of a “hangman” bracket is shown in Figure 2.

In contrast, these symbols are absent from the Stebbing text. Whereas Gaddis repeatedly uses distinctive brackets and geometric symbols in his copy of Aristotle, no such visual identifiers appear in the Stebbing text. The most important passages in Philosophy and the Physicists are pinpointed by extra vertical lines (up to three at a time) and, for the especially significant passages, by Gaddis’s handwritten commentary.

Speaking more broadly, Gaddis may have been inspired to pick up Philosophy and the Physicists because of the great friction between philosophical systems and scientific theories described therein. Stebbing’s book examines the works of two scientists: Sir Arthur Eddington and Sir James Jeans. Both are physicists by profession, but authors as well, working to communicate science to a non-specialist audience. Stebbing attacks them for their failure to properly achieve this task. She sharply critiques their efforts to address the philosophical implications of physical theories in her chapter, “The Common Reader and the Popularizing Scientist.” Their metaphors and allegories, she says, obfuscate rather than clarify. Attacking Jeans for his lack of communicative transparency, Stebbing states that he has an obligation to “avoid cheap emotionalism and specious appeals, and to write as clearly as the difficult nature of the subject-matter permits” (6). The following sentence Gaddis annotated with a double vertical line: “Of this obligation Sir James Jeans seems to be totally unaware, whilst Sir Arthur Eddington, in his desire to be entertaining, befools the reader into a state of serious mental confusion” (6-7).

Gaddis annotated not only Stebbing’s commentary, but a few of the excerpts that she provides from Eddington’s or Jeans’s writing. In these, he seems partial to the deterministic view. Double vertical marks highlight Stebbing’s evaluation of Jeans: “We need also to avoid the not uncommon mistake of supposing that the uncertainty relations show that there is anything indeterminate in Nature, or that science has now had to become inaccurate. Yet this is what Jeans seems to suppose. ‘Heisenberg now makes it appear’, he says, ‘that Nature abhors accuracy and precision above all things’” (183). A further refutation of Jeans is marked with double and triple vertical lines, the triplet beginning at “Principle”: “This is surely an absurd mistake. Granted that, in a given case, the initial conditions are determined as precisely as the Principle of Uncertainty permits, then the probability of all subsequent states is determined by exact laws” (183).

Another note that supports the deterministic worldview, “ie det not ind logic” is written next to the selection: “The scientists have inferred (not clairvoyantly foreseen) what will happen, and they have subsequently verified the prediction. The future has been anticipated only in the sense that extrapolations have been made and have been shown to be correct” (203). Gaddis’s note shows that deterministic, not indeterminate logic, is responsible for the accuracy of scientific prediction. In the same paragraph, a vertical line marks off “If what happens is determined, then it must be predetermined. Here ‘must’ signifies that predetermination is involved in the meaning of determination.”

Identifying Gaddis’s own stance is difficult, as it was taken in his annotation of Eddington’s defense of the dense language of his books. Marked with a vertical line: “‘Non-technical books are very often a target for criticism simply because they are non-technical.’ [Eddington] adds, ‘I take it that the aim of such books must be to convey exact thought in inexact language. The author has abjured the technical terms and mathematical symbols which are the recognized means of securing exact expression …” (7). Adjacent, Gaddis has made a note: “e.g. Weiner.” In Gaddis’s library, there are no authors with that surname. This note surely refers to “Norbert Wiener,” the author of Cybernetics: The Human Use of Human Beings, whose influence on Gaddis’s interpretation of Stebbing will be documented.

The triumph of scientism/science (=objective, ie measurable/manageable reality)

Gaddis’s draft notes indicate the importance of “Weiner entropy, Weiner pp” to the player project (“From Kent or other” notes). The folder of 1950s-era notes on the player piano project contains a clearer explanation of Wiener’s relevance: “Dr Norbert Wiener, in his excellent book on Player Pianos titled The Human Use &c, gets off the subject often but does on page 210 tell of the engineer who bought one for the wrong purposes &c” (“.5” notes). Unfortunately, the copy of Cybernetics that Gaddis had at the time was a different edition from the one now stored in the Washington University archives, which is only 199 pages, and almost completely devoid of annotations.8Except, on the inside of the back flap is scrawled a colloquial message in large lettering, blue ink: “Muriel, have the john unplugged before you enter it,” referring to Muriel Oxenberg Murphy, with whom Gaddis had a long-term relationship following the dissolution of two marriages. They did not enter their relationship until the late 1970s; the intimate nature of Gaddis’s note dates the reading of this copy from that period onwards. Could Gaddis have lost his original copy, and bought it again out of nostalgia? We may never know.

The only—very spare—annotations in this edition appear on its Page 183: a few centimeters of underlining, and a bracket. Unsurprisingly, this is the very passage on the engineer’s “wrong purposes” in buying a player piano mentioned in Gaddis’s notes: this quotation may have been so important to his work on Agapē Agape that Gaddis repurchased the book purely to revisit it (bracket spans from “I can” to “production of music”):

Our papers have been making a great deal of American “know-how” ever since we had the misfortune to discover the atomic bomb. There is one quality more important than “know-how” and we cannot accuse the United States of any undue amount of it. This is “know-what” by which we determine not only how to accomplish our purposes, but what our purposes are to be. I can distinguish between the two by an example. Some years ago, a prominent American engineer bought an expensive player-piano. It became clear after a week or two that this purchase did not correspond to any particular interest in the music played by the piano but rather to an overwhelming interest in the piano mechanism. For this gentleman, the player-piano was not a means of producing music, but a means of giving some inventor the chance of showing how skillful he was at overcoming certain difficulties in the production of music. This is an estimable attitude in a second-year high-school student. How estimable it is in one of those on whom the whole cultural future of the country depends, I leave to the reader. (Wiener 183)

The engineer, who wishes to understand how the player piano’s components function, is emblematic for Gaddis’s note on “The triumph of scientism/science.” The engineer is focused on a “measurable/manageable reality”: he is more interested in how the machine’s mechanical parts work together than in the music produced. Gaddis’s anxiety about this mentality shows that his consistent selection of passages related to physical determinacy does not necessarily entail the affirmation of those principles. Instead, he is trying to define their implications more clearly.

The mind modern as mechanistic (ie programmed people)

Gaddis furthers his investigation of determinacy by highlighting the use of deterministic language to mechanistically describe the workings of the universe—observing reality as if events were inevitable, spat out from an enormous cosmic player piano roll. He marks the following passage with a vertical line that spans the length of the page:

The upshot of the acceptance of the Principle of Uncertainty is the admission that the basis of quantum laws is statistical, so that the conception of causal laws ceases to have application. Further, it takes away any reasons there may have been for regarding the material universe as a huge machine. The machine-picture has never been worked out in detail; but the ideal of a machine has been imaginatively grasped by physicists and, in consequence, language appropriate to the behaviour of machines has been very extensively used. The rejection of this machine-language is an important gain. It makes for clearer thinking with regard to the philosophical implications of physics. (183)

The passage posits some ideas that Gaddis may have supported, namely the rejection of machine-related language. Other pages of Stebbing’s book evidence Gaddis’s attention to the implications of the descriptive language surrounding physics. Stebbing contrasts the anxieties of three different thinkers, again marked with a long vertical line:

Planck is anxious to refute indeterminacy in physics in order to save the dignity of man. Eddington is anxious to increase the amount of indeterminacy, recently introduced into physics, in order to safeguard our feeling of responsibility. Sir Herbert Samuel is afraid lest the denial of determinism should make man the sport of chance and lead him to irresponsibility in action and increase of unreason in politics and life. (220)

Of these viewpoints, Gaddis’s neighboring annotations most align him with Eddington. Stebbing’s book argues against Eddington’s obscurantist writing style, but that bars neither Stebbing from salvaging ideas from Eddington’s work, nor Gaddis from advocating them.

Gaddis has drawn a vertical mark next to a comment that Eddington makes on the measurable amount of indeterminacy in the world, and its effect on human behavior: “‘If our new-found freedom,’ says Eddington, ‘is like that of the mass of .001 mgm. which is only allowed to stray mm. in a thousand years, it is not much to boast of. The physical results do not spontaneously suggest any higher degree of freedom than this’” (215). Seventeen pages later, the annotation, “mm? v.p. 215,” is placed next to a section marked with a penciled vertical:

The conception of human beings as created objects, as manufactured articles, pervades the language used by those who are troubled about man’s responsibility […] Jeans, however, offers us the hope that, owing to Heisenberg’s Principle, ‘it is almost as though the joints of the universe had somehow worked loose, as though its mechanism had developed a certain amount of “play”, such as we find in a well-worn engine’ […] this ‘loose-jointedness’ […] is a sign that not everything is destined to happen exactly as it does happen. (232)

Jeans suggests that some amount of unpredictability is unavoidable in any system, even one with set laws. Gaddis, recalling previous pages, succinctly captures Jeans’s point with his large “mm” annotation. However tentatively he associates this fraction of spatial freedom with the “play” of the loosened joints of the universe, Gaddis nonetheless resists the perceived irresponsibility that Heisenberg’s Principle allows to human beings who subscribe to a physically indeterminate worldview. That not every event must happen “exactly as it does happen” supports the assertion that the basis of quantum laws is statistical; sometimes, the event with the lower predicted probability occurs. What’s more, Gaddis follows this passage with the penciled note, “v. alienation in the assembly line,” suggesting that he considered unlikely, spontaneous outcomes in human behavior an essential way of distinguishing humans from machines (233). This matches a specific line from the 1950s-era page of notes from Box 118, Folder 413, reproduced in Figure 1, which reads, “Alienation (and the player/machine) – dignity of work (e dignity of liesure)” (“organized subsidy” notes).

In another passage on Jeans, Gaddis writes “the plan” next to the section “… to speak of laws as producing this, that, or the other is, then, not considered by Jeans to be inconsistent with dismissing ‘every trace of anthropomorphism from our minds’” (14). This shows Jeans’s fundamental reason for maintaining his advocacy of physical indeterminacy: he rejects determinism on the basis that it makes human behavior seem mechanistic. Given the negative connotations of Gaddis’s note on “programmed people,” his note “the plan” appears to support the production of deterministic laws, but without the erasure of anthropomorphism from explanations for human behavior. Gaddis reads against Jeans, proposing a more optimistic picture of a deterministic philosophy: one in which planning and spontaneity are forms of resistance against inevitability.

Determinism (e behaviorism) vs radicalism

Given his interest in a deterministic worldview, Gaddis seemed intent on figuring out the rules that govern not what we do, but instead why we do. Ironically, his obsessive PP research suggests he was too preoccupied by the why of his project. He devoted far more time to the process of finding material to help him justify the production of final work, than in producing the final work.

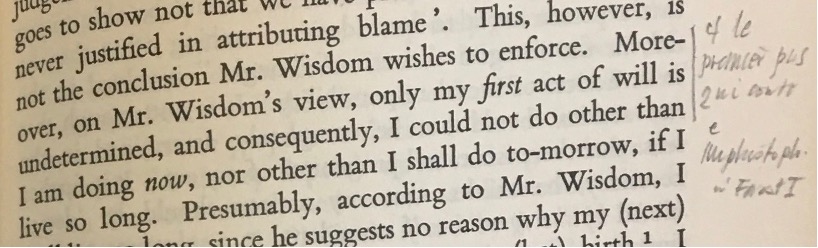

What is the ultimate why of the world’s working? Gaddis indicates his stance against a theological explanation, placing a checkmark next to “That a God such as a Christian could worship originally created this world is surely not to be inferred from the laws of physical phenomena” (260). And to speak of another divinity’s relationship to causality, a dastardly character from literature makes an appearance in the note “cf le premièr pas qui conte e Mephistoph. ~Faust I” (French: “the first step matters & Mephistopheles”),9Carolyn MacFarlane, who hails from Quebec, helped me with this translation! written next to the Stebbing passage marked by a vertical line: “Moreover … only my first act of will is undetermined, and consequently, I could not do other than I am doing now, nor other than I shall do to-morrow, if I live so long” (235 - see Figure 3).

This translation is verified by Gaddis’s working notebook for The Recognitions. There we find the same concept rendered in English. Gaddis cites Goethe’s Faust, a Bohn’s Popular Library edition translated by Anna Swanwick: “Mephistopheles (Goethe’s Faust) entering by door which Faust has made it impossible for him to leave by; it is the only place he can use as exit. M- says that only the first choice is free, the second bound by it” (“Faust Pentagram” page).10Directly beneath this paragraph is this note: “Here note the Muriel story—the whole sound of the knock=knock.” At the bottom of the same notebook page (see Figure 4), Gaddis has drawn a pentagram, with the note beside: “Pentagram with which Faust held Mephistopheles in his study.” The top of the page offers a more serious statement: “That there shall be no disguises in the writing.”

In the same way that Mephistopheles materializes on Earth, undisguised but nonetheless withholding many secrets, this “no disguises” approach aptly describes the controlled, although not ascetic aesthetic of The Recognitions. Altogether, this journal page helps show the profound responsibility that Gaddis assigns to the individual when one undertakes an act. The first step of a chain reaction is a great burden, and this burden is amplified when the agent executes a dangerous deed, aware that the act is forbidden.

Following this Stebbing note toward Gaddis’s annotations of Faust reveals a host of annotations gracing Goethe’s poetic dialogue. Of most relevance to Stebbing is a conversation that Mephistopheles, while dressed in Faust’s robes, has with one of Faust’s students. Thick double vertical lines begin at “And prove to you,” (earlier unannotated lines provided for context):

The mind’s spontaneous acts, till now

As eating and as drinking free,

Require a process ; —one ! two ! three !

In truth the subtle web of thought

Is like the weaver’s fabric wrought :

One treadle moves a thousand lines,

Swift dart the shuttles to and fro,

Unseen the threads together flow,

A thousand knots one stroke combines.

Then forward steps your sage to show,

And prove to you, it must be so ;

The first being so, and so the second,

The third and fourth deduc’d we see ;

And if there were no first and second,

Nor third nor fourth would ever be.

This, scholars of all countries prize, —

Yet ‘mong themselves no weavers rise. (Goethe 61-2)

The passage recalls the descriptions of automation that Gaddis annotates in Aristotle’s Politics—the lyres that strum, the looms that weave themselves. However, Gaddis’s (and Goethe’s) focus is not on the poetry of machines, necessarily, but the pas taken: after the initiating step, each subsequent step is inevitable. No student wandering in Faust’s study should take Mephistopheles at his word, as Gaddis cautions in cursive letters written parallel with the margin some sixty pages after the lines above: “note all through see Mephistopheles’ cynicism” (Goethe 125). Mephistopheles’s conclusion that “This, scholars of all countries prize, — / Yet ‘mong themselves no weavers rise” digs into an existential question. These two lines question the role of predetermination in the actions of human beings. Mephistopheles recognizes the creative whirl of ideas in the mind, using the metaphor of a loom and the convergence of unseen threads to describe the psychological process of producing a thought. The first step he takes represents the conversion of thought into action. However, the conclusion that no scholars are “weavers”—that none can become completely self-aware of the processes that undergird their thoughts—suggests that thought cannot be completely controlled. The wily devil points to the conceptual distance between the ability to think (doable), and being able to know how thinking occurs (impossible).

Given that the decision to act is a “stroke” that combines “a thousand knots,” we can understand the “loom” of the mind as automated. Mephistopheles’s complex metaphor presents the mind as a hybrid: spontaneous thoughts and acts are explainable as the result of automation, but the mind is also an instrument that responds to human choice. The Stebbing note “the first step matters” testifies to Gaddis’s inventiveness. By associating Mephistopheles’s metaphysical quandaries with the mid-twentieth century philosophy of science, Gaddis straddles the Evil One on the border between indeterminate and deterministic conceptions of human behavior.

The textual constellation between Stebbing, Wiener, and Goethe provides the complex knot that Gaddis must unravel. Together, the texts present difficult questions for how and why time and human actions unfold as they do. In Faust, the determinism that stamps both the first and fourth steps in a sequence depicts Stebbing’s conception that “the last elements in the sequence are in some sense ‘contained’ in the first elements.” The question of how a causal sequence unfolds is clear, but Goethe does not address the why. Stebbing’s reference (and Gaddis’s annotating nods) to Wiener in Philosophy and the Physicists then raises questions about why to investigate determinacy at all. Wiener addresses the why behind human action when he questions “what our purposes are to be”—a phrase that Gaddis underlined in his repurchased copy of Cybernetics.

As Wiener identifies, answering the why is an act of the kind Mephistopheles called a “first step”: a direction that can be decided. If Gaddis’s attention to that statement is any indication, he believed that to actively decide one’s own purposes is to lay the groundwork for proper choices.

Problem: player = (Newtonian physics) determinism – from which we are freed with the new physics?

Stepping away from questions of willpower and choice, we consider Gaddis’s broader position on humans operating in societies, as related to the player. Whereas Aristotle’s Politics prompted Gaddis to load the player project with philosophical baggage about democratic values, talent, labor, and the production of art, Gaddis’s reading of Stebbing adds the laws of physics to the tally. A vertical mark is made next to the key passage:

… the universe is regarded as a closed system in which everything that happens is causally necessary. The suggestion is of an inevitable unrolling of a causal sequence in which the last elements in the sequence are in some sense ‘contained’ in the first elements. The metaphor of ‘unrolling’ is obscure; it is the source of much confused thinking on this topic as on other topics. (211-2)

Gaddis notes in the margin, “cf player piano roll,” suggesting not only an etymological origin for the metaphor, but a philosophical picture of the universe overwhelming in its amount of determinacy (212). The laws of the universe are preprogrammed, rather than subject to indeterminate physical rules. The comparison between the player piano roll and the sequential unfurling of time sharply diminishes the possibility of the occurrence of a theoretical event; the perforated paper already says it all.

Regarding Gaddis’s opinion of theoretical events, it is helpful to look to The Recognitions. These humorous lines are spoken by an unidentified individual at a Christmas Eve Party that later disintegrates into chaos:

—Of course you’re familiar with Heisenberg’s Principle of Uncertainty. Have you ever observed sand fleas? Well I’m working on a film which not only substantiates it but illustrates perfectly the metaphor of the theoretic and the real situation. And after all, what else is there? (Recognitions 600)

This dialogue captures the problem of trying to understand the world in both deterministic and relativistic terms: the world cannot be fully comprehended in both senses simultaneously and must be experienced as a metaphor. The “new physics” cannot completely extricate the world from the determinism of the player piano. Overall, Gaddis’s annotations reveal his continuing concerns for a world that, because of the principles of relativity, suffers from increasing philosophical destabilization. The split between Newtonian determinism and Einsteinian relativism was a foundational change in physics and mathematics that urged extensive reconceptualization of the order of nature, and in Gaddis’s eyes, the desire to make sense of this world only gets more complicated. A note from the archive displays this: “The RECOGNITIONS as title I like perfectly because it implies the impossibility of escape from a (the) pattern” (“Item Page 85” notes). For Gaddis, one such pattern that seemed inescapable was the alienation induced by mechanization.

Alienation (and the player/machine) – dignity of work (e dignity of liesure)

The final line we will consider from the 1950s notes page contains Gaddis’s most pungent comparison between humans and machines: humans as objects with given functions. The handwritten note “v. alienation in the assembly line” accompanies the passage:

Sir William Bragg (writing in 1935) urges us not to let ourselves be ‘oppressed by unnecessary fears that we are but helpless cogs in a machine’, but his ground for hope does not seem to lie in a recognition of the inappropriateness of the machine-image but in the fact that we ‘are unable, at present, to interpret in full what we observe’. (Stebbing 232-3)

If the “v.” means “as opposed to,” then Gaddis is conceiving the assembly line, with its negative Marxian connotations, as a machine composed of human cogs. Out of all the annotated passages in Stebbing’s book, this one is unique because Gaddis targets the assembly line as requiring the use of machine-inspired language, precisely because it is a dehumanizing system. “Alienation (and the player/machine)” is a direct correlate to the penciled note “v. alienation in the assembly line,” at the top right corner of page 233 in Philosophy and the Physicists (see Figure 5).

The player piano’s ability to alienate people from their own creativity is implied by these notes, and this concept is the ideological thrust of Agapē Agape.

The archive contains additional references to “Alienation (and the player/machine).” Gaddis’s J R drafts display attempts to refine the ideas that reappear in Agapē Agape. In J R, Gaddis offers us a deeply realized fictional universe, born from the seeds of years of reading and contemplation, in which creative types are alienated from their own creativity and business-minded individuals are perfectly adapted to mechanization. Granted, the book does not contain a single instance of the phrase “assembly line,” but it presents characters as machine elements in a system and as mechanized/automized. One grim synopsis-note for J R contrasts the fates of these groups: “Book is about the war between those with a charisma (Bast -& artists) vs. those without (JR et al.). And – that mechanization/automation can replace only the latter – but – it is to them the world belongs, so the former must be made over in their image or eliminated” (“Points” notes).

Whether the character be a failing artist or an entrepreneurially-minded fifth grader, Gaddis always keeps the behavioral flaws of his creations in perspective, giving depth to their fictional existences. Much like the intertextual annotations which could be identified as the distant origins of their full-fledged personalities, Gaddis’s characters are often driven by a mix of philosophies and principles, sometimes with profound consequences. Indeterminacy may grant mm of freedom in the physical laws of the universe; likewise, Gaddis never permits his characters so much freedom that they are absolved from their behavior. They cannot outrun the fallout of their choices.11Characters in The Recognitions meet their due. The evil Basil Valentine is stabbed; the overambitious Stanley dies in a church collapse. We cannot, however, forget the redemptive powers of truth and art. In the intro to Goethe’s Faust, Gaddis has underlined in bold pencil, “Any sketch of the dramatic structure of ‘Faust’ in which the Second Part is not fully taken into consideration is bound to be a hopeless failure” (xiv). Faust I concludes with the eponymous character’s descent to Hell, Faust II in his ascent to Heaven. The valiant, flawed creatives in his work endure such turbulent questions about what creative work is truly worth doing precisely because they have chosen to embrace their creativity—and Gaddis himself, championing the long, difficult work required to grow one’s artistic talent in the face of a creative shortcut like the player piano, was no exception.

Conclusions

Overall, the annotation of Philosophy and the Physicists reveals several intensive artistic challenges that Gaddis presented himself in the attempt to refine his conception of determinacy, within the larger framework of his player piano project. In response to the note-page of major themes, his experiments with certain terms and phrases generate problems. How can he convince us that determinism is not dehumanizing? How can he show us the validity of his player piano roll picture of the universe, while deploying mechanistic descriptions of human behavior only in cases of workplace alienation? This is where the theme of indeterminacy comes in. Gaddis’s contrast between Bast and JR shows that indeterminacy is less about human irresponsibility and unpredictable physics outcomes, and more about the potential for exercising the various attributes of artistic charisma: creativity, innovation, and spontaneity.

The actions of automatons and of humans who perform tasks replaceable by machine cannot be theoretically uncertain. Assembly lines and industries are sites where nearly everything has a predicted outcome. In contrast, artists can harness the freedom to invent while being embedded in a deterministic social system with clear rules and boundaries. The only problem is that the artist continually feels pitted against society. The shortage of indeterminacy in social fluidity prevents society from recognizing the importance of the artist; for this reason, Gaddis writes J R on the premise that a war is being waged for the value of the artist.

But in the end, as a useful term, “indeterminacy” and its connotations fail to please Gaddis, even if they do allow artists some creative leeway. The annotations consistently show that Gaddis was trying to pursue the different valences of determinacy as effective and accurate ways of describing all aspects of human life, from industrial to behavioral, from Goethe to Wiener. The depth of Gaddis’s poetic associations across sources is a testament to the surprising flexibility of his mind. He was willing to assimilate and synthesize a broad range of literary traditions in the effort to produce a cohesive, multilayered novel. Better, he could pluck useful ideas out from opposing systems; Gaddis learns as much from Eddington and Jeans as he does from Stebbing herself. For scholars hoping to gain further insight into Gaddis’s vibrant inner life and creative process, Philosophy and the Physicists is but one of many possible entry points into a deeply developed intellectual network that can further our engagement with Gaddis’s novels. The player materials are but one of many intellectually stimulating projects ripe for excavation in the Gaddis archive. An accidental encounter with an intentional marking is a powerful way to meet Gaddis’s voice, rewarding scholars the more incisively they explore his archives, and particularly his library.

J R never uses the word “indeterminacy,” and despite that Christmas-party dialogue on Heisenberg, the mention of indeterminacy is a rare occurrence in The Recognitions. We do hear of “indetermination,” though. Wyatt Gwyon, reposing in the still, quiet dining room of his family home after his father has just left, observes the silence punctured by a “sharp, unfriendly sound,” possibly a bell from the kitchen; Gwyon disrupts the stillness with the motion of his own hand, setting down his glass, the silence punctured again by “the sound of a lute,” likely the musical clink of the glass on the table (398). But the note is erased almost as soon as it arrives, due to the wholly unmusical acoustics of the dining room having “quickly killed” the sound with “ruthless angles,” preventing the sound from moving “upon undulant planes never before explored” (398). Reminiscent of an anechoic chamber, the room’s oppressive silence resists music and motion, restoring itself to its inert default, thereby affirming that music is “the illusion of motion, the sin of possibility, the devil-inspired absurdity of indetermination” (398). Art is the enemy of pure determinism, the path to realms yet unexplored. But we can’t be sure it will persist beyond a moment, or reach an audience. In a sense, this passage captures how the perfectionistic Gaddis seemed to treat his own intellectual forays: briefly compelling moments of music, that don’t presume the power to endure or alter reality.

His notes on Philosophy and the Physicists embody his mind at work, but it would be decades before the results of all this source-synthesizing found final form in Agapē Agape. While Philosophy and the Physicists helps Gaddis raise profound questions about key concepts for the player project, Stebbing’s text is not so much a transition point toward the correct, precise language for his next project, so much as it is one node in a sea of circuity.

Lacking direct testimony from Gaddis, it is difficult to determine how he truly felt about his discoveries. Was he dissatisfied with the quality of his findings, leading to his setting these notes aside? More optimistically, he saw the very process of making these intellectual connections as valuable, bridging vast distances of time and geography to conduct meaningful, satisfying conversations with those whom he chose as his peers. We see Gaddis’s roving, connective process powerfully described in Joseph Tabbi’s afterword to Agapē Agape:

Against all forgeries, simulations, and wastes of the world, this was the one consolation that Gaddis held on to during the last stages of composition: that the life of the mind in collaboration with other minds, the fraternal love that he felt in his recollection of a friend no longer here, and the disciplined recognition of the achievements of past writers would give to his work a staying power beyond his own, finally human, powers of caring and invention. (112)

Having dwelled in this paper on the life of Gaddis’s mind and his art of collaboration, we might add that the sense of fraternal love extended to those whom he read. Gaddis’s dedication to his intellectual network spanned multiple centuries and continents, in his immense effort to deliver a desperately important message into his own time. For decades, until Agapē Agape was at last published on a day William Gaddis would never see, this habit of conversing, then traveling onward, persisted. He continually tested the waters, finding familiar patterns, precisely in order to work out how to depart from them in directions of his own.

What makes identity? Specifically, identity as constructed through a piece of fiction? Whereas Tabbi might view Gaddis’s “disciplined recognition” as a way of standing with a persistent tradition, Gaddis’s library shows us that his sense of identity and intellectual location was malleable, with the freedom to option different voices within a tradition. He possessed a great curiosity, but without feeling obliged to consistent agreement with those whom he deeply admired. Perhaps we could see this indeterminacy as one of the central rules in Gaddis’s reading identity: indeterminacy as a necessity for arriving at yet a different conclusion—as, finally, a means of invention.

Works Cited

From the Manuscripts of William Gaddis

Gaddis, William. “.5” notes. Undated. William Gaddis Papers. Collection MSS049. Box 119, Folder 419. Special Collections Manuscripts, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO.

———. “Faust pentagram” on page 25 of record notebook for The Recognitions. 1950s. William Gaddis Papers. Collection MSS049. Box 54, Folder 248. Special Collections Manuscripts, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO.

———. “From Kent or other” notes. Undated. William Gaddis Papers. Collection MSS049. Box 122, Folder 429. Special Collections Manuscripts, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO.

———. “Item Page 85” notes. Undated. William Gaddis Papers. Collection MSS049. Box 32, Folder 206. Special Collections Manuscripts, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO.

———. “organized subsidy as suppression” notes. 1950s. William Gaddis Papers. Collection MSS049. Box 118, Folder 413. Special Collections Manuscripts, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO.

———. “Points,” notes. Undated. William Gaddis Papers. Collection MSS049. Box 67, Folder 273. Special Collections Manuscripts, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO.

From the Personal Library of William Gaddis

Aristotle. Aristotle’s Politics and Poetics, Trans. Benjamin Jowett & Thomas Twining. Compass Books, Viking Press, 1957.

Gaddis, William. The Recognitions. 1st ed., Harcourt, Brace and Co, 1955.

Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von. Goethe’s Faust, Ed. Karl Breul. Trans. Anna Swanwick. Bohn’s Popular Library, G. Bell and Sons, Ltd., 1914.

Stebbing, L. Susan. Philosophy and the Physicists. 1937. Dover Books on Science, Dover Publications, 1958.

Tolstoy, Leo. War and Peace, Trans. Constance Garnett. Modern Library, 1940.

Wiener, Norbert. The Human Use of Human Beings: Cybernetics and Society. 2d ed. rev., Doubleday Anchor Books, 1954.

Works by, and scholarship on, William Gaddis

Chetwynd, Ali and Joel Minor. “William Gaddis’s Unpublished Stories and Novel-Prototypes: An Archival Guide.” Electronic Book Review (June 2024). https://doi.org/10.7273/ebr-gadcen5-1

Gaddis, William. Agapē Agape. Afterword by Joseph Tabbi. Viking, 2002.

———. J R [1975]. New York Review Books, 2020.

———. “Stop Player. Joke No. 4.” The Atlantic (July 1951): 92-3.

———. The Letters of William Gaddis, ed. Steven Moore. 1st ed., Dalkey Archive Press, 2013.

———. The Recognitions [1955]. Dalkey Archive Press, 2015.

———. The Rush for Second Place: Essays and Occasional Writings, ed. Joseph Tabbi. Penguin Books, 2002.

Klebes, Martin. “Gaddis before Bernhard before Gaddis,” in Thomas Bernhard’s Afterlives, ed. Olaf Berwald, Stephen Dowden, & Gregor Thuswaldner. Bloomsbury, 2020: 117-135

Moore, Steven. William Gaddis, Expanded Edition. Bloomsbury, 2015.

Tabbi, Joseph. “Afterword,” in Agapē Agape. 97-113