Juvenilia in the William Gaddis Papers

Kate Michelson Goldkamp surveys the Juvenilia preserved in Gaddis’s archive, finding, among other things, early prefigurations of his “delight[] in the macabre” in some illustrated mini-stories, hints of the boy JR's worldview in studies of US geography, and doodles that prefigure some of the published fiction’s hand-drawn illustrations.

Various materials from the Gaddis Archive by William Gaddis, Copyright © 2024 The Estate of William Gaddis, used by permission of the Wylie Literary Agency (UK) Limited Due to the copyrighted archival material reproduced here, this article is published under a stricter version of open access than the usual Electronic Book Review article: a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 license. All reproductions of material published here must be cited; no part of the article or its quoted material may be reproduced for commercial purposes; and the materials may not be repurposed and recombined with other material except in direct academic citation – https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

The term “juvenilia” refers to the work of writers and artists created during childhood. In most cases, these works remain unpublished and only appear after their creator has become renowned, if they survive at all. Washington University Libraries is very lucky to have some wonderful examples of writers’ juvenilia throughout the Modern Literature Collection. This includes a small but rich collection of items in the William Gaddis Papers. Some academic and creative work has previously drawn on Gaddis’ earliest writings, like Joseph Tabbi’s 2015 biography, Crystal Alberts’s introductory survey of the archive (2007), and Marshall Klimasewiski’s creative reorganization of Gaddis’s unpublished language (2018). Some of his earliest letters were included in the first three pages of the Steven Moore-edited Letters of William Gaddis (2013/23), which otherwise focuses on letters Gaddis sent after 1940, when he was 17. The current guide will therefore try to highlight some of the juvenilia items not previously mentioned in the scholarship. While we may not be able to make any definitive links between his childhood and mature works, juvenilia can shed some light on Gaddis’s early life, and at the very least the items in the archive are delightful to look through.

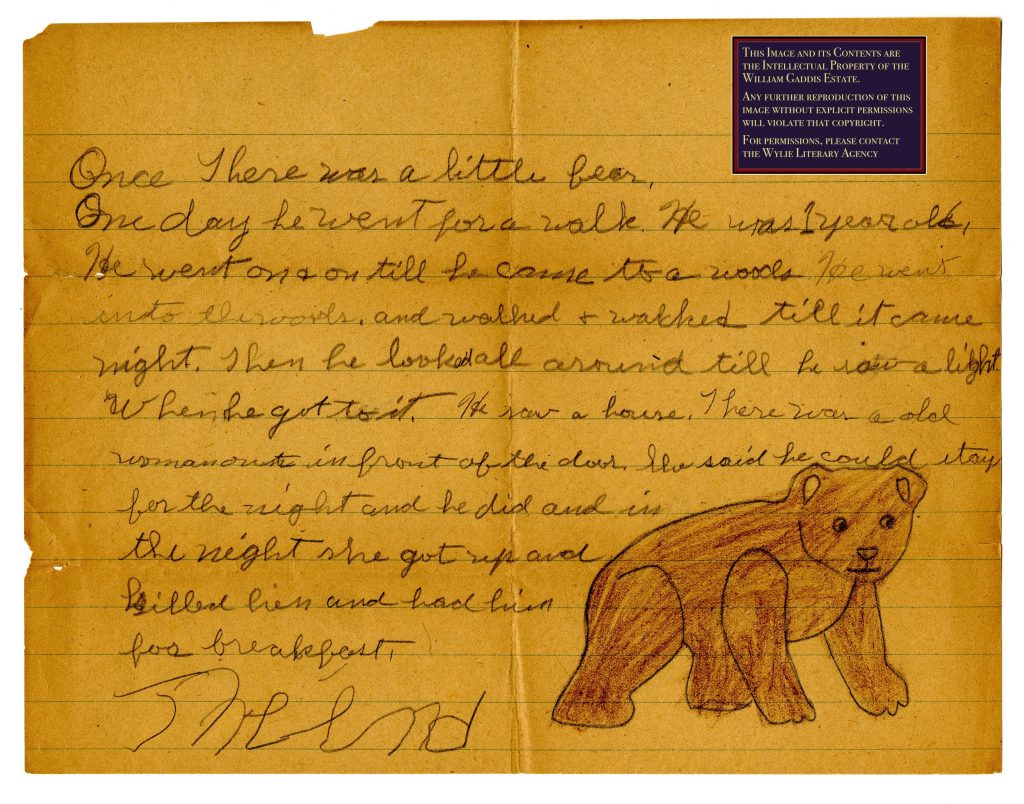

The majority of the archived Gaddis juvenilia consists of schoolwork from his time at Merricourt Boarding School in Berlin, Connecticut. Among the spelling quizzes, French language work, and dictation exercises, there are some wonderful gems that show us Gaddis’s creative development. Many of his earliest stories (all compiled in Gaddis Archive, Box 95, Folder 12: “Merricourt Boarding School work”) are notable for their dark, somewhat comic endings. All written on the same ruled paper with accompanying drawings, they appear to be done for school assignments, as one of them has a note on it instructing that the children “choose a picture & write about it” Ultimately it does not seem possible to fully determine whether all the stories were schoolwork or whether any were written by choice, but they do have a distinct sensibility. A story Gaddis wrote about a bear starts out pleasantly enough, but at the end takes a sharp turn (see Figure 1):1

Once There was a little bear,

One day he went for a walk. He was 1 years old, He went on & on till he came to a woods. He went into the woods, and walked & walked till it came night. Then he looked all around till he saw a light. When he got to it. He saw a house. There was a old woman out in front of the door. She said he could stay for the night and he did and in the night she got up and killed him and had him for breakfast.

The end

Though the story above may be the most striking, it is far from the only story with an unhappy ending. When finally receiving a pair of skates that he had been wishing for, a bunny goes out with his friends to use them and promptly falls in a mud puddle. A ship is attacked by cannibals and sinks. A narrative about a poor couple going to market ends with their horse and buggy running away (with the couple’s cat inside) and the subsequent death of the couple.

How did Gaddis develop this early fictional worldview? Looking through his second grade seatwork book (Gaddis Archive, Box 95, Folder 13), there are several fictional reading comprehension exercises, and a few of these seem to also end unhappily, although theirs seem to have a specific moral lesson behind them. In “Piggy’s Birthday Party”, a piglet’s mother has instructed him not to eat any of the treats before the party starts. However, the piglet eats everything in the house and when his mother arrives with his party guests, they discover a sick piglet and no food to be had. Another story, “Look Before You Leap,” tells of a young rabbit failing to heed his mother’s advice and jumping on what he thinks is a log but turns out to be an alligator (thankfully the rabbit survives). These sorts of moral tales are very common in stories for children, and perhaps they had an influence on young Gaddis’s own compositions. However, his original stories are darker than the cautionary tales in his seatwork book, and, with the possible exception of the rabbit and the roller skates, they do not appear to have an obvious moral. The stories in his seatwork book have a clear cause-and-effect plot that connects the actions of the characters to their fates. Gaddis’s own tales have no such strong through-line, but rather take random turns for the worse. Perhaps this is simply due to a novice writer still grappling with the mechanics of plot, or perhaps this is a young boy delighting in the macabre. Keeping in mind Gaddis’s novels, one might like to think that it is more of the latter.

Besides the short story compositions, there are also two books of geography work, one labeled “fourth grade” and one undated (Gaddis Archive, Box 95, Folder 13), which occasionally read like prototypes of the schoolwork in J R. The undated one is especially rich in detail: handmade and secured with brads, Gaddis has detailed different regions of the United States with carefully hand-drawn maps and summaries of the states, including their geographic “contours,” climates, and industries. Indeed, there is a heavy emphasis on the economies of the country; several of the maps specifically show the concentration of various types of farming and mining in different regions.The maps include colored areas denoting corn and coal production, and some very detailed ones showing gold, silver, copper, and petroleum. The silver map, for example, shows several western states spattered with dots, with a note at the bottom: “One dot is 2,000,000. oz.” Each section is finished with “THE END.” Sadly, as Alaska was not a state at the time, there is no entry for it, which robs us of the chance to compare Billy Gaddis’s report to the one on “Alsaka” in J R, which similarly itemizes “precios metals,” “timber,” “coal and oil” and “wild life” (J R 465).

In addition to Gaddis’s schoolwork, there is also correspondence from his time at Merricourt, written mostly to his mother Edith but also to other family members and friends. While not literary works per se, we can see the burgeoning creativity of the young writer in these letters. Most of these are handwritten, but occasionally there are typed letters. One that stands out in relation to the later fiction is a page that appears to be drafts of a “business” letter for an imaginary company (Gaddis Archive, Box 1, Folder 7: “Outgoing Correspondence 1934”). The top of the page includes the date (January 2, 1934) and an opening salutation of “Dear sir,” but quickly devolves into random typings of gibberish. Further down, Gaddis starts again:

Dear Sir

We are on the standard basis. As we do not no

nowhat to say about the football uniforms or the footballs and we do not sell cowboy suits.Here is what we sell; uniforms for chaufeurs & police. That is all.

Very sencerily yours,

Billy Gaddis

President

The letter is addressed to Ed Maynard, “Plymoth,” New Hampshire. Ed Maynard was a real sporting goods company—in a previous letter dated January 29, 1933, Gaddis wrote his mother that he received “the thing from ‘Ed Maynard’” (Gaddis Archive, Box 1, Folder 6). Gaddis was eleven years old when he wrote the 1934 letter, which immediately brings to mind the preteen capitalist J R Vansant.

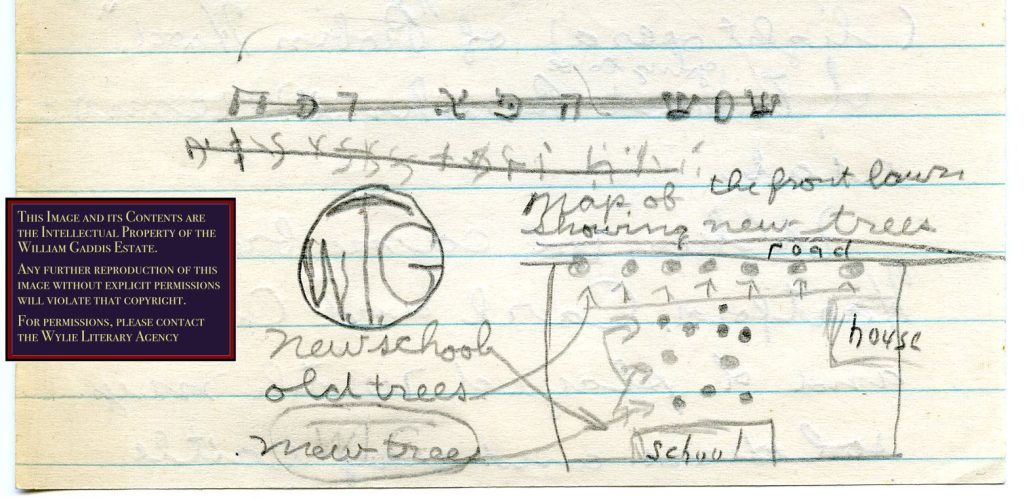

As he grows older, his letters home become more elaborate, often with small drawings and diagrams outlining something he is explaining in the text of the letter. In a letter from November 7, 1932, when he was nine, Gaddis writes his mother about a memorial service he attended at the Second Congregational Church in Berlin for the congregation’s late pastor, Samuel Asa Fiske (Gaddis Archive, Box 1, Folder 5: “Outgoing Correspondence 1932”). He describes the memorial tablet installed and gives a pictorial representation of it. Sure enough, a Google search of “Samuel Asa Fiske Berlin Connecticut” brings up a copy of the service program for sale on a bookseller’s website.2 The program has a reproduction of the tablet that proves the nine-year-old Gaddis’s copy to be an accurate representation. A letter to his mother, dated April 26 1933, has a postscript that includes two instances of his self-designed “WTG” monogram (see Figure 2), as well as a map outlining the landscaping of new and old trees in relationship to the school and house (Gaddis Archive, Box 1, Folder 6: “Outgoing Correspondence 1933).

J R, you may recall, marks Bast’s alienation from his childhood home by the destruction of its “old trees.” Also notable here is the crossed out line of Hebrew above the map, which gives us an early glimpse of a lifelong interest in writing styles and calligraphy.3 The monograms here especially call up the hand-drawn sketches for the J R Family of Companies logo, attributed to “the agency boys,” which the novel takes a half-page to reproduce (J R 570). Gaddis continued to doodle on his drafts throughout his life, examples of which can be seen constantly in the archive. His drafts also include numerous examples of calligraphy, frontispiece sketches, and so on. The juvenilia establishes just how early he developed this habit, which occasionally made its way into his published novels.

These items are merely a handful of the treasures lurking in this little corner of the William Gaddis Papers. I believe there is a lot more that could be gleaned from formal examination of these works, both on their own and in relation to Gaddis’s later work and life.

Works Cited

Alberts, Crystal. “Valuable Dregs: William Gaddis, the Life of an Artist.” in Paper Empire: William Gaddis and the World System, eds. Joseph Tabbi and Rone Shavers. University of Alabama Press, 2007: 231-55.

Gaddis, William. J R. (1975). New York Review Books, 2020.

Klimasewiski, Marshall. “William Gaddis and the Thoughts of Others.” Conjunctions 70 (Spring 2018): 326-341.

Moore, Steven (ed.), The Letters of William Gaddis, 2nd ed. New York Review Books, 2023.

Second Grade Seatwork for Silent Reading. Webster Publishing Company, 1927.

Tabbi, Joseph. Nobody Grew but the Business: On the Life and Work of William Gaddis. Northwestern University Press, 2015.

William Gaddis Papers. Julian Edison Department of Special Collections, Washington University Libraries.

Footnotes

-

All quotations from the juvenilia reproduced here retain the original spelling and grammar. ↩

-

“Samuel Asa Fiske Memorial 2nd Congo Berlin CT 1932.” The Jumping Frog, https://www.thejumpingfrog.com/product/2022113/Samuel-Asa-Fiske-Memorial-2nd-Congo-Berlin-CT-1932. Accessed 14 July 2023. ↩

-

My thanks to the members of an online Bryn Mawr College Alumnae/i community for confirming that this script was indeed Hebrew. ↩

Cite this essay

Goldkamp, Kate Michelson. "Juvenilia in the William Gaddis Papers" Electronic Book Review, 5 May 2024, https://doi.org/10.7273/ebr-gadcent6-1