"Not Going Where I Was Knowing": Time and Direction in the Postmodernism of Gertrude Stein and Caroline Bergvall

In an essay spanning modernist and postmodernist poetics, Lynley Edmeades demonstrates how postmodern poetry cultivates “present-ness” by drawing on Lyotard’s concept of “constancy,” Gertrude Stein’s notion of “continuous present” and Caroline Bergvall’s adherence to “non-linearity.”

Introduction: Postmodernism’s Doing

In the concluding statements of his book, The Postmodern Condition, Lyotard proposes that we can only understand modernism through the advent of postmodernism itself. “Postmodernism thus understood,” he says, “is not modernism at its end but in the nascent state, and this state is constant” (1988a, 81). He goes on:

The postmodern would be that which, in the modern, puts forward the unpresentable in presentation itself; that which denies the solace of good forms, the consensus of a taste which would make it possible to share collectively the nostalgia for the unattainable; that which searches for new presentations, not in order to enjoy them but in order to impart a stronger sense of the unpresentable. (ibid.)

For Lyotard then, postmodernism is an act of inversion: in the act of naming something, we turn our gaze away from a previously conceived and categorized subject, and towards that which has not yet been named, or that which is in the process of being named or presented. That is, in its unpresentable-ness, it is in a state of becoming, and the very process of becoming is the thing in itself. As such, the emphasis is on the doing rather than the done – the gerund form rather than the past tense of the verb – and in the act of doing, the subject obtains its character. What we would otherwise conceive of as being a thing obtains its existence in, and only in, the process of becoming that same thing.

Lyotard also suggests, in his notes towards a definition of this otherwise elusive concept, that by working within the remit of postmodernism, artists and writers reject the possibility of that very remit. “The artist and writer,” he postulates, “are working without rules in order to formulate the rules,” and that, because of the absence of governing rules, “work and text have the characters of an event” (ibid., emphasis in original). The event holds significance for the postmodern artist or writer because he or she is attempting to work beyond the rules and is therefore situating him- or herself within that very process. The postmodern artist or writer draws attention to the process, the ever-eruptive, never-representable Now. In doing so, they express the process as the work in itself, a rupture that evades categorization and naming, and that cannot be narrated. Lyotard writes that “rules and categories are what the work of art is itself looking for,” and that it is in the process of “looking for” rules and categories that the work actually occurs. His focus is precisely the doing, rather than the done, the gerund form of the verb, and thus, upon the act of “looking,” rather than what is being looked at.

Swiss sound artist and scholar, Salomé Voegelin, expands Lyotard’s brand of event-based postmodernism in her book, Listening to Noise and Silence (2010). Owing to her interest in temporal arts, her interpretation of this passage hones in on Lyotard’s use of the word “constant.” Voegelin argues that postmodernism, for Lyotard, is “not something in itself, but is simply the condition of present-ness, continually transitive and potentially anything as long as it is here and now” (62). Thus, Voegelin’s reading of Lyotard’s postmodernism asks for an examination of the event, rather than the outcome of that event. It asks us to move away from modernist ideals, such as aesthetic autonomy and “radical separation from the culture of everyday life” (Huyssen, vii), and to give oneself up to a potential “displacement” or “incoherence” aligned with postmodern aesthetics (Bray, Gibbons and McHale 2012, 6). Voegelin’s reading encourages us to think about what has been made fixed or definite, and how it might look if it returns to, or is encouraged to hover, in a state of indeterminacy or temporality.

Voegelin is writing much more recently than Lyotard, and her comments here speak back to, and reflect some of, the more recent developments in scholarship on the sonic arts. The last twenty years has seen more intellectual examination of sound art and sonicality than ever before, and Voegelin has been a great contributor to this body of work (see, for example, Dyson, Kahn, Ikoniadou, LaBelle). But what is important about her observation of Lyotard’s conception of postmodernism is, I feel, her emphasis on time and the event. Where Lyotard says, “the work and text have the characters of an event,” and that “this state is constant,” Voegelin re-words this particular constancy to be “the condition of present-ness,” and “anything as long as it is here and now.” In the postmodern then, the unpresentable becomes not only presentable, but also present; it is precisely the “here and now” that the work is centered on. Lyotard proposes something similar when he says “[one must] become open to the ‘it happens that’ rather than the ‘what happens’” (1988b, 18). For Voegelin, vis-à-vis Lyotard, the event maintains precedence, and the attention to that event attunes us to its occurrence within the “here and now.” So how does this “here and now,” this “it happens that,” manifest itself in postmodern poetry? What does that tell us about artists and writers working within the remit of postmodernism and, furthermore, what might their work then tell us about postmodernism as a moment – or a series of moments – in literary history?

Stein’s “Present Spot of Time”

In many ways, Gertrude Stein can be viewed as an early exemplar of postmodern literature, and many postmodern scholars have sought to claim her as such (Berry 1992; Perloff 2002; Schmitz 1986). In her early compositions we can detect a number of characteristics that would later become synonymous with postmodern betrothals: a radical indeterminacy, a decentering of coherent narratives, a movement away from the unity and totality of modernism, an increased emphasis on the reader’s active role in the construction of meaning, and the adoption of “small local strategies that generate a series of interpretive moments no one of which is definitive” (Berry 3–4). Stein called this the “continuous present,” a compositional technique that becomes Stein’s modus operandi during the early years of her career (Stein 1971, 25). As a postmodern writer, Stein’s continuous present exemplifies the (non)representation of a potential Now, where “the primacy of the immediate phenomenological situation, the prolonged moment of perception” encourages the reader to inhabit a continuous Now (Bergen 220).

Perhaps the most widely discussed of Stein’s compositional principles, Donald Sutherland describes Stein’s continuous present as “the isolation of present internal time” (1951, 174). It can be traced back to Stein’s early studies in psychology in the U.S. with William James, particularly his theories of knowledge, experience, and perception. “To think a thing as past,” James says, “is to think it amongst the objects or in the direction of the objects which at the present moment appear affected by this quality” (570). He suggests that “what is past, to be known as past, must be known with what is present, and during the ‘present’ spot of time” (591–592). In other words, our knowledge exists only insofar as it happens in the present moment, and without paying attention to that present moment, the past and the future would cease to exist.

For Stein, to capture this “present spot of time” meant moving away from a traditional narrative of past-present-future, and towards a more direct experience of now. She would look to use narrative as a “present thing,” or to write within a particular “spot of time.” Robert Haas argues that, for writing to be “real” for Stein it must be a description of “now” (49). In one of her four lectures during her 1934 U.S. tour, Stein says:

When one used to think of narrative one meant a telling of what is happening in successive moments of its happening the quality of telling depending upon the conviction of the one telling that there was a distinct succession in happening. (1935, 17)

Stein would later go on to argue that what is inherently wrong with traditional narration was the fact that it cannot draw on a description of “now,” and that it therefore cannot escape the linearity of time passing. By writing through durational time, the successive “nows” would inevitably keep shifting. However, what we can see in this quote, and in her early aesthetic, is Stein trying to accomplish a dynamic of what is “happening” within the space of writing, at a point where she believed it possible to escape what she regarded as staid or standard narrative forms. As such, in her early work the emphasis is on a direct experience, and a continuous present is the motivating factor for the work.

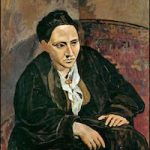

Stein left the shadow of James in 1902 after deciding against pursuing a career in psychiatric medicine, opting instead for the artistic nourishment of Paris. As such, we can see Stein developing the concept of continuous present in her work as early as 1910–1912, with some of her early word-portraits, such as “Ada,” “Matisse,” and “Picasso.” Stein later rewrote the earlier portrait of Picasso for Vanity Fair, renaming it “If I Told Him: A Completed Portrait of Picasso” (1923). This second version of the portrait might have been her last attempt to write a final, completed portrait of her friend and artistic brethren, with whom she had shared many creative years with and who had painted her portrait two decades earlier.

Figure 1: Pablo Picasso, Portrait of Gertrude Stein (1905–6)

By seeking to achieve a continuous present in the portrait, Stein’s “If I Told Him” draws our attention to experience rather than representation: rather than describe Picasso, Stein tries to generate an experience of his genius through words. In doing so, she promotes a sensorial encounter with language rather than a categorized linguistic experience. Rather than seeking to signify or describe, the portrait promotes an experience of language, both sonically and linguistically. It is not a description of Picasso, but a description of “now.” This particular “now” has Picasso in it and it begins and ends at each simultaneous moment:

Now.

Not now.

And now.

Now.

(2008, 190)

While the text refers to something that is happening outside of “now,” that is, in the past or the future, it fails to engage in past or future verb tenses. While it states “not now,” and thereby indicates to a space and time outside of this present moment, it does so by drawing its reader into that particular moment in time. The text does not refer to something that has been or to something that is about to be; it does not refer to a past or future event outside what is happening within the text. The actual event is still happening “now.” That is, it is an appeal to a direct experience, where Stein attempts to have her reader or listener hover in a continuous present. As such, this use of a continuous present also draws us into the temporality of the language. In the passage above, any verb form has been omitted, so there is effectively no tense at all. By being kept in a state of un-tense, as it were, we are drawn into of the actual duration of reading or listening.

To achieve and maintain this continuous present, Stein deliberately displaces certain aspects of our regular interpretive structures of language, such as syntax and grammar. This, in turn, heightens our awareness of the temporality of language while drawing attention to its own lack of tense:

Presently.

Exactly do they do.

First exactly.

Exactly do they do too.

First exactly.

And first exactly.

(2008, 191)

By repeatedly upsetting the linearity of traditional narration, Stein’s poetic technique draws attention to itself in time, and as such, does not encourage a reflection upon meaning. Stein’s present, Donald Sutherland says, “is so continuous it does not allow any retrospect or expectation,” and is a “completely self-contained thing” (1990, 9–10).1 Sutherland likens this to Stein’s particular mode of counting, where rather than counting individual units as one, two, three, four, she would prefer to say one and one and one and one.

[A] continuous present… would be one in which each unit, even if identical or nearly with the previous one, is still, in its present, a completely self-contained thing, as when you say one and one, the second one is a completely present existence in itself, and does not depend, as two does or three does, on a preceding one or two. (ibid.)

What we expect from the more familiar experience of narrative progression is thrown into disarray in the passage “first exactly” as we are never encouraged to reflect upon the meaning or our movement through the text. “Presently” we are told is “exactly,” and “exactly do they do.” From here, we are thrust back to the beginning, with “first.” Imagine how different the narrative would be if the chosen word was “firstly” rather than “exactly,” for example. The word “firstly” signifies that something will follow, “secondly” or “thirdly” perhaps. It illustrates that there is a hierarchy of events. However, at no point in the use of “first” or “and first exactly” is there a signifier of future tense. We are continuously pulled back into the present.

Stein makes strong use of the imperative in the piece too, which is another way of evading tense in language. The imperative is always without tense in English and, as such, is used to continually draw us into the happening of language inside the piece, rather than encouraging us to reflect on it. Passages such as the one below exhibit this performative aspect to the work:

Now actively repeat at all, now actively repeat at all, now actively repeat at all.

Have hold and hear, actively repeat at all.

(2008, 191)

This excerpt is almost in the form of a command – do this, now do this – much like a recitation or a catechism. But yet, as the words are uttered, we are doing exactly what the text says to do; that is, we are “actively repeating.” We are not only saying the words, but performing their meaning at the same time; we are doing and saying, simultaneously. Being in the present tense and using this performative aspect allows Stein to appeal to a durational self, a self that simultaneously enacts the meaning of the language while remaining in the language.

We can detect here some of the basic characteristics of a postmodern literature: there is no master narrative that drives the portrait; the meaning remains indeterminate and open to the interpretation of the reader. Furthermore, there is an absolute emphasis on constancy, now-ness and present-ness. “If I Told Him” is an attempt to construct a present image, something that exists in the here and now, and that continually activates itself upon being heard or read. In it the present is continuous; Stein’s “now” is not “before” or “later,” but right “now,” even as I write this or you read it. The portrait intends to manufacture its own sets of rules and to present a “spot of time” and space that would normally be “unpresentable.” It maintains a continuous present by creating and maintaining an ecology of now-ness, within a reality that it constructs for itself. In that reality our linguistic and literary expectations of coherence become null and void and, for the piece to function as continuously present, it insists on occupancy and constancy within that present. Rather than repetition being a violation of the continuous present, Stein insists that in the continuous present “there is no such thing as repetition, only insistence” (1988, 166).2 Each time an act is repeated, each instant is unique; rather than counting “one, two, three” for example, she suggests we count “one and one and one.” That is, each instant is ontologically different and therefore inhabits a new and particular Now.

Bergvall’s Directionless Travel

For Caroline Bergvall, present-ness occurs in a slightly different fashion. Where Stein uses insistence and repetition, Bergvall muddies the waters between languages and histories, in such a way that our standard linguistic understanding becomes defunct. Bergvall is plurilingual. She writes predominantly in English, and while her native tongue is Norwegian, she is also fluent in French. This enables her to look at language anew and, in the act of writing in English, to feel her way through a language in a largely sensorial way; her ear is finely tuned to the sonicality of language, and the visual plays a large part in her overall aesthetic. In a lecture about the lyric in avant-garde poetry, Romana Huk proposes a reading of Bergvall’s poetry as a “new lyric of self-preservation” (2015).3 By self-preservation, I take Huk to suggest the new lyric or post-avant-garde idea of a kind of new personal element to poetry, a confessional lyric remodeled through experimental poetics and political, cultural, and linguistic exchange. The idea that I would like to pick up on, however, in attempting to link Bergvall with Stein and this Lyotardian idea of “constancy,” is Huk’s suggestion that by working with this “intolerably personal,” highly vulnerable literature, Bergvall approaches a kind of “non-linear progress.” Instead, I want to modify Huk’s observation and suggest that Bergvall’s work portrays time outside the parameters of progression: her work is simply non-linear, without progression in either direction. It is this non-linearity or directionless travel that enables her to shift between languages and time periods and an attempt to urge her readers to withhold preconceived notions of fixed linguistic and historical categories. In turn, and not unlike Stein’s efforts to maintain a continuous present, Bergvall urges a kind of movement that ruptures our commonplace notions of linear time. Rather than attempt to suspend duration, like Stein, Bergvall instead interrupts duration, asking her readers to forego preconceived categories in the interest of attaining a multi-linguistic, ahistorical perspective.

Issues of plurilingualism drive Bergvall towards this place of betweenness, where she constantly seeks to undermine one language with the use of another, questioning whether one tongue can say what the other is trying to do, whether one can do what the other is trying to say. From her most recent work, Drift (2014), a piece called “North 6” exhibits this kind of betweenness:

Ottar said that Northmen land was very swyde long and very swyde narrow told his ohman that he to the north of ealra northmen northmost lived said that he lived on them land northward long tha westsæ said that that land is swipe long north but his is all waste but for a few sticks with Finnas hunting on wintra and on sumera fishing be there sea said that he would fan out hu longe that land nortright lies and whether any one to the north of the westenne lived then fared he northright see them lande. (33)

On a rudimentary level, we might actually see something of Stein’s nonsense aesthetic here: it does not make grammatical or syntactic sense. Upon further examination, however, we discover there is a lot more to the text. “Ottar” is the Norse form of “Ohthere,” a Viking Age Norwegian seafarer who travelled to England in the 9th century, and told his tale to King Alfred. His is one of the earliest known seafaring stories that remain in circulation today and it survives through the Old Norse tale of Ohthere and Wulfstan (Cassidy and Ringler 184–85).

Beyond this historiographical reading, the piece rewards closer examination and starts to unfold some of Bergvall’s attempts at this non-linearity. Upon first encountering the word “swipe,” we could assume a generic understanding of the term. One might “take a swipe” at something, or a sweeping blow with a club or bat. It might refer to a physical swing or a punch. It could be a critical or cutting remark or, in a more vernacular fashion, it could mean to steal something - “I swiped this from my sister,” for example. In common technological parlance, it might refer to the movement we make with a credit card for payment, “just swipe your card here…” However, looking into it further - with the Old Norse tale in mind - we start to see its evolution: swipe comes from swiþe, which comes from swīþe, which is, in turn, derived from swīðe. The Þ, or “thorn,” in swīþe is taken from the runic alphabet, and is used to represent the interdental spirant, ð, which is pronounced “eth,” or like the “th” in thy (Cassidy and Ringler, 16). In Old English, “swithe” is an adverb (unlike the noun or the verb in our contemporary diction), which can mean “very,” “fiercely,” “greatly,” “swiftly,” or “readily” (Cassidy and Ringler, 472–473) to name but a few synonyms.In the excerpt from Bergvall’s Drift we see two versions of the word: twice in the first line (swyde) and once in the fourth line (swipe). What is worth noting here is the way in which the multiple uses of the word causes us to hover between languages. In the first line, for example, we see a word we do not recognize in English, but which turns out to be a repetition or emphasis: “very swythe long” simply means “very very long.” On the other hand, when we reach the fourth line, the word has morphed from “swythe” to “swipe” - something we can recognize in English - but is clearly not meant to be taken for its modern English meaning: rather than it being “that land is swipe long” is makes more sense if we read it “that land is very long.” At the same time, there is a sense here that Bergvall is herself taking a “swipe” at her modern English reader. She literally steals a word (where the word itself can also mean “steal”) from one time period and places it in another. In doing so, Bergvall does not let us fall into this or that time period, but urges us to hover in a state of in-betweenness. Bergvall’s work is characterized by a temporality of drift, where we might be able to suspend our attempts to categorize the work into any specific period. All historical moments are equally accessible in any potential sequence as the reader moves from word to word. We are literally adrift in Bergvall’s Drift.

Bergvall’s work also draws on the idea of directionless travel, a kind meandering or a state of drift, and she does this on both a textual and contextual level. Several pages after our learning about Ottar in the previous excerpt, we arrive at an eight-piece poem called “Hafville.” The first installment begins with standard word-like structures: “The fair wind failed. The wind dropped. Winds were unfavourable straightaway” (36). “Hafville 2” starts to lose some grammatical and syntactic integrity; units of language start to break down and bleed into one another: “We mbarkt and sailed but a fog so th but a fog so the but a fog so th th th th thik k overed us that we could scarcely see the poop or the prow of the boa t” (37). By the time get to the end of “Hafville 4,” we are left with just consonants:

Figure 2: Excerpt from “Hafville 4” (p. 39)

After two and a half pages of this ticking “t” composition, the stuttering turns into something slightly legible, which eventually becomes “t go off course hafville,” and “Did not go where I was knowing hafville…” Bergvall offers no translation of this word “hafville.” A quick check in an Old Norse dictionary leads to a similar linguistic construction, “hafvilla,” which means “at sea,” having no sense of direction, or directionless. We know the word is significant; Bergvall’s repetition of it cannot go unnoticed. What is more is that it resonates closely with her overall project here, tropes of betweenness or “drifting” amongst identities, places, languages. One section of the book touches on a 2011 case in which seventy-two migrants from Nigeria, Ghana, Sudan, Ethiopia, and Eritrea departed from the port of Gargash, Libya, bound for Lampedusa Island, Italy. The rubber boat was never fit to carry the passengers the entire way, and while they encountered a number of passing ships over the course of five to six days, the migrants were never offered any help. They were left to drift and eventually drifted back into Libyan waters. The few who survived the journey were taken to prison in Zlitan. Bergvall tells this true story of a migrational drift with excerpts from survivors’ testimonies and intersperses it with satellite images of the vessel at sea and astral constellations, supposedly those visible from sea for those on the journey.

After the repetition of “t,” the piece takes a common adage, “I know not where I was going,” and inverts it to “not go where I was knowing.” This draws attention to Bergvall’s overall project in Drift and provides an insight into the kind of instability of both identity and language. To attempt to “not go where I was knowing” implies a kind of relinquishing of control and reflects the sentiment of the helpless Libyan migrants. It asserts a sense of knowledge in part, but rather than adhering to that knowledge, it suggests moving in the other, unknown direction. For Bergvall, the subject of Drift is directionlessness, moving towards an unknown, having come through a place of unease - as exemplified in the loss of syntactic and linguistic threads - to finally resign to, and reside in, a state of in-betweenness. It is in a state of drifting; that is, it retains its verb-ness amidst any attempts to make it a noun.

Bergvall’s project encourages her readers and listeners to suspend their states of knowledge, with the hope of finding home in the space in-between. In this space, a certain “hafvilla” becomes a desired state, whereby the idealism of knowledge, totality, and reason become both unnecessary and undesirable. It inspires a degree of uncertainty, whereby that very uncertainty is based upon the possibility of certainty itself. As such, it asks us to give in to our not-knowing, and to hover in a state of becoming. Rather than emphasizing the reflexive, finalized state of knowing, Bergvall’s Drift suggests that we un-know, or at least try to go where we do not know, as a way of resisting the narrative hierarchy of past-present-future and the potential oversimplified binaries of direct translation. Lyotard suggests that, in order to encounter the “it happens that,” we must “impoverish [our] mind, clean it out as much as possible, so that [we] make it incapable of anticipating the meaning” (1988b, 18), and Bergvall exemplifies the resistance to such an anticipation of meaning. Her work rewards the resolve to un-know, to remain for as long as possible in this state of “impoverishment,” or in a state of drift.

Conclusion: Postmodernism as “It Happens”

Romana Huk proposes framing Bergvall as a post-postmodernist. Through Lyotard’s conception of “constancy,” however, I suggest we cannot think about Stein or Bergvall as inhabiting any particular period or school of literature. I want to suggest that we can look at Stein and Bergvall, vis-à-vis Lyotard as a triumvirate who offer a still-viable, still-provocative brand of postmodernism. By paying attention to the precise present of a potential Now, the “unpresentable in presentation itself” (Lyotard 1988a, 81), of “not going where I was knowing,” Stein and Bergvall exemplify some of the varieties of postmodern writing. Through their attention to the metaphysics of time in language, the rejection of dichotomies of translation, Stein and Bergvall exist for us as possible indicators of how some characteristics of postmodern poetry can encourage readers and listeners to suspend their belief in a totality of knowledge, and to maintain a level of engagement within the parameters of the work itself. Their work shows postmodernisms endless iteration or inventiveness in trying to (not) represent this Now. Or, as Lyotard might frame it, to “endure occurrences as ‘directly’ as possible,” so to be “incapable of anticipating the meaning, the ‘What’ of the ‘It happens’” (1988b, 18). To do so would be to hover in a state of continuous present, of “hafvilla,” or drift. Both Stein’s and Bergvall’s postmodernism asks us to reside in a gerund state: of becoming, rather than already become. This now. This. Now this.

Notes 1 At a 2015 Modernist Studies Association conference, I heard a paper delivered by Birgit Van Puymbroeck (Ghent University), titled “Gertrude Stein and Politics: ‘Let Us Save China’.” Puymbroeck discussed several of Stein’s unpublished manuscripts, one of which was called ‘Let Us Save China,’ which includes an excerpt of the narrator “counting as Chinamen,” by numbering “one and one and one and one,” and so regarding all elements as equal units. Puymbroeck implied in her paper that Stein’s “counting as Chinamen” was a more egalitarian approach than regular linear counting (which maintains a hierarchy). I think Donald Sutherland is referring to this unpublished text in his writings, although he does not reference it.In “Portraits and Repetition,” Stein adds that in “expressing any thing there can be no repetition because the essence of that expression is insistence, and if you insist you must each time use emphasis and if you use emphasis it is not possible while anybody is alive that they should use exactly the same emphasis” (1988 167).

Works Cited

Bergen, Kristin. “Modernist and Future Ex-Modernist: Postwar Stein.” Primary Stein: Returning to the Writing of Gertrude Stein. Eds. Janet Boyd and Sharon J. Kirsch. Plymouth, UK: Lexington Books, 2014. Print.

Bergvall, Caroline. Drift. Brooklyn and Callicoon, NY: Nightboat Books, 2014. Print.

Berry, Ellen E. Curved Thought and Textual Wandering: Gertrude Stein’s Postmodernism. Ann Arbor: U Michigan Press, 1992. Print.

Bray, Joe, Alison Gibbons and Brian McHale, eds. The Routledge Companion to Experimental Literature. London and New York: Routledge, 2012. Print.

Cassidy, Frederic G., and Richard N. Ringler, eds. Bright’s Old English Grammar and Reader, 3rd ed. New York: Holt, Rhinehart and Winston, Inc., 1971). Print.

Dyson, Frances. Sounding New Media: Immersion and Embodiment in the Arts and Culture. Berkeley: U California Press, 2009. Print

Haas, Robert Bartlett, ed. A Primer for the Gradual Understanding of Gertrude Stein. Los Angeles: Black Sparrow Press, 1971. Print.

Huk, Romana. “New British Schools: The Return of the Lyric and the Transatlantic Avant-Garde.” University of Otago, New Zealand, 11 May 2015. Lecture.

Huyssen, Andreas. After the Great Divide: Modernism, Mass Culture, Postmodernism. Bloomington and Indiana: Indiana U Press, 1986. Print.

Ikoniadou, Eleni. The Rhythmic Event: Art, Media, and the Sonic. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2014. Print.

James, William. Principles of Psychology, Vol. 1. London and Cambridge, MA: Harvard U Press, 1981. Print

Kahn, Douglas. Noise, Water, Meat: A History of Sound in the Arts. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999. Print.

LaBelle, Brandon. Acoustic Territories: Sound Culture & Everyday Life. New York: Continuum, 2010. Print

Lyotard, Jean-François. The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. Trans. Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi. Minneapolis, MN: U of Minnesota Press, 1988a. Print.

———. Peregrinations: Law, Form, Event. New York: Columbia U Press, 1988b. Print.

Perloff, Marjorie. 21st-Century Modernism: The “New” Poetics. Maldern, MA: Blackwell, 2002. Print.

Schmitz, Neil. “Gertrude Stein as Postmodernist: The Rhetoric of Tender Buttons.” Critical Essays on Gertrude Stein. Ed. Michael J. Hoffman. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1986. 117–29. Print.

Stein, Gertrude. Narration: Four Lectures. Chicago U Press, 1935. Print.

———. “Composition as Explanation.” Writings and Lectures, 1909–1945. Ed. Patricia Meyerowitz. Baltimore, MD: Penguin, 1971. 84–94. Print.

———. Lectures in America. London: Virago, 1988. Print.

———. Selections. Ed. Joan Retallack. Berkeley: U California Press, 2008. Print.

Sutherland, Donald. Gertrude Stein: A Biography of Her Work. New Haven: Yale U Press, 1951. Print.

———. “Gertrude Stein and the Twentieth Century.” Gertrude Stein Advanced. Ed. Richard Kostelanetz. Jefferson, NC, and London: McFarland, 1990. Print.

Voegelin, Salomé. Listening to Noise and Silence: Towards a Philosophy of Sound Art. London and New York: Bloomsbury, 2010. Print.

Footnotes

-

At a 2015 Modernist Studies Association conference, I heard a paper delivered by Birgit Van Puymbroeck (Ghent University), titled “Gertrude Stein and Politics: ‘Let Us Save China’.” Puymbroeck discussed several of Stein’s unpublished manuscripts, one of which was called ‘Let Us Save China,’ which includes an excerpt of the narrator “counting as Chinamen,” by numbering “one and one and one and one,” and so regarding all elements as equal units. Puymbroeck implied in her paper that Stein’s “counting as Chinamen” was a more egalitarian approach than regular linear counting (which maintains a hierarchy). I think Donald Sutherland is referring to this unpublished text in his writings, although he does not reference it. ↩

-

In “Portraits and Repetition,” Stein adds that in “expressing any thing there can be no repetition because the essence of that expression is insistence, and if you insist you must each time use emphasis and if you use emphasis it is not possible while anybody is alive that they should use exactly the same emphasis” (1988 167). ↩

-

This lecture forms the basis for Huk’s contribution to Modernist Legacies: Trends and Faultlines in British Poetry Today, eds. Abigail Lang and David Nowell Smith (Palgrave Macmillan, 2015: 59–78). ↩

Cite this essay

Edmeades, Lynley. ""Not Going Where I Was Knowing": Time and Direction in the Postmodernism of Gertrude Stein and Caroline Bergvall" Electronic Book Review, 4 December 2016, https://electronicbookreview.com/publications/not-going-where-i-was-knowing-time-and-direction-in-the-postmodernism-of-gertrude-stein-and-caroline-bergvall/