The Uses of Postmodernism

Jacob Edmond argues that while postmodernism might be useless as a theoretical concept or periodization, it nevertheless illuminates changes, both local and global, in the final decades of the twentieth century. Edmond analyzes the uses of postmodernism in the United States, New Zealand, Russia, and China. He shows how the various and even contradictory uses of the term postmodernism allowed it to represent both sides in the unfolding tension between globalization and localism in late twentieth-century culture.

What’s the use of postmodernism? Asked in 1979 about the “vagaries of a term such as ‘post-modern,’” Roman Jakobson responded: “I try not to use even Modernism, because what is Modernism, it depends on who writes it and at what moment!” (171). In the early 1990s, Marjorie Perloff suggested that a great deal of discussion of postmodernism “sounds more like The Cat in the Hat…than like a serious attempt to understand what is happening in late twentieth-century culture” (“Postmodernism” 176). Almost two decades later, the term has largely disappeared from literary and cultural criticism. There would seem to be little use in discussing postmodernism when the term and the concepts or artistic styles that it was meant to signify now seem completely outmoded.

Here, I want to propose a couple of possible uses for this seemingly outdated term. First, postmodernism can serve as a prompt to periodization. Postmodernism draws attention to the need for a better parsing of the last century or so of cultural production than the current fallbacks of modern and contemporary allow. However, postmodernism might also lead us to consider what is at stake in periodizing our recent past. On the one hand, postmodernism prompts us to ask whether there are other more nuanced ways to think about the cultural, economic, philosophical, and geopolitical shifts of the last century. On the other hand, it raises questions about the unacknowledged spatial and temporal hierarchies that attend the very act of periodization.

Second, tracking the various uses of the term and its cognates in other languages, such as houxiandaizhuyi 后现代主义and постмодернизм, provides a rich vein for comparative inquiry into the unequal dynamics of the world literary system and the variety of uses to which aesthetic practices and theories are put as they circulate within this system. At first glance, studying the spread of the term only exacerbates the habit of thinking periods through a spatial hierarchy of center and periphery and a temporal hierarchy of origin, development, and belatedness, a habit that inhibits attention to the complexities of cultural production, consumption, and change on a global scale. Yet a properly nuanced history of postmodernism’s uses can highlight not only the temporal and spatial hierarchies but also the networks of relation that shaped the term’s use during the technological, social, and geopolitical flux of the late twentieth century.

Periodization

One use of postmodernism might be as a means to address the stretching of the contemporary to encompass everything after modernism, which, the Modernist Studies Association tells us, runs “from the later nineteenth- through the mid-twentieth century.” The period after modernism so defined now stands at roughly seventy years, a similar length of time to that encompassed by the MSA’s definition and over twice as long as the core canonical modernist period of, say, 1910 to 1940. That is a lot of history and a huge amount of literary history, considering that the publication of literature has “increased steadily and exponentially” over each of those decades, even prior to the World Wide Web (Dworkin 7). This is a problem not just of history but also of discipline. We have institutions for modernist studies and jobs in modernist studies. But for literature since the mid-twentieth century, we are often stuck with one overarching “contemporary” that refers to texts produced from last week to decades before many of today’s scholars were born. This use of the term contemporary leaves those who work on the mid to late twentieth century in an institutional no man’s land - on the job market and in publishing - between modernist studies and the study of the latest trends in literature. Witness, for example, the seeming temporal gap between two excellent book series in Columbia University Press’s current literary studies list: Modernist Latitudes and Literature Now. One use of postmodernism might be to address this temporal gap by bracketing off a part of the last seventy years, say, 1945 to 1990 or 1960 to 1990, depending on the historical or stylistic criteria one wanted to apply. To use postmodernism in this way no doubt risks perpetuating the failure of literary studies “to institutionalize a reasonable range of competing concepts that would mitigate some of the obvious limitations of periodization as a method” and exacerbating the “chronological narcissism” whereby periods closer to the present are more compressed than those more historically distant (Hayot 740, 746). Still, postmodernism at least has the mitigating advantage of allowing us to question the assumptions that sit behind existing institutionalized periods like “modernist” and “contemporary.”

Even if we accept the need to insert a term between modern and contemporary, why not use another category? What historical, conceptual, or stylistic reasons do we have for using postmodernism over another term? And what might we gain or lose by cutting up the decades in different ways? Some obvious alternative periods might stress geopolitics: Cold War (1945-1991) and post-Cold War (1992-). Another possible marker of change is technology and especially dominant media: we might, for instance, distinguish the age of television (1950s-early 1990s) from the Internet age (1993-present). Or we could turn to an economically inflected technological account, such as Alan Liu’s distinction between the informating (1950s-1970s) and networking (1982-) labor paradigms that follow the automating age (nineteenth century-1950s).

Or, combining the economic with the geopolitical, we might distinguish the period of anti-colonial struggles and large-scale European decolonization (1940s-1970s) from the neocolonial moment of increasingly global corporations and of the worldwide rise of neoliberalism, marked by the ascendency of Deng Xiaoping, Margaret Thatcher, and Ronald Reagan (circa 1980-). This post-1980 period, however termed, has also been characterized by the economic and geopolitical rise of China and India and so a dramatic shift in global power eastwards.

Since the publication of Fredric Jameson’s 1984 essay “Postmodernism; or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism,” postmodernism, twinned with its historical periodization postmodernity, has been used to describe the “cultural logic” that accompanies some of these historical changes, particularly in the world economic system and in technology. But the term arguably has less leverage than these other more concrete historical accounts.

What is undeniable, however, is that the term postmodernism has played a role in attempts to address these changes. Jameson’s 1984 essay, for instance, responds to the shifting geopolitics of the late Cold War. The essay begins by invoking the “‘crisis’ of Leninism” and so the collapse in Western Marxists’ belief in one alternative to capitalism (Jameson 53). Yet, whereas today China is at the heart of global capitalism, Jameson’s essay depends on the counterexample of China as a “collective…‘subject of history’” for its definition of the fragmented subjectivity that is the “cultural logic of late capitalism” (Jameson 74).

Charles Olson’s use of the term several decades earlier, in 1951, was equally motivated by a sense of historical rupture: by his desire to break with a modernity that had led to the horrors of Auschwitz and with the colonialism and emergent neocolonial capitalism that he witnessed during his wartime military service. Like Jameson, Olson looked to China as a collective subjective that could be opposed to Western capitalism. For Olson, however, the terms were reversed. He opposed the new “post-modern world” and his “projective” poetry to a pernicious modernity and an “estranged” or alienated “modern” subject (9 and 20 August 1951 letters to Robert Creeley; qtd. in Butterick 6). Olson’s epochal hailing of the postmodern explicitly appealed to the historic founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 (Anderson 9-10). By 1984, however, China had begun its slow but sure embrace of what Jameson termed “late capitalism.” Jameson’s echoing appeal to China was thus historically anachronistic, just as his account of postmodernism inverted Olson’s earlier use of the term.

As these examples illustrate, “generalizations about historical periods typically contain covert assumptions about space that privilege one location over others” (Friedman, “Periodizing Modernism” 426). And these covert spatial hierarchies are usually accompanied by “the concepts of originality, development, and belatedness that lie at the center of the modern world view” (Hayot 745). Jameson makes China the counterexample to the West’s postmodernity. Inversely, Olson’s postmodern emerges only out of the non-Western world, of which China is a privileged representative. The very term postmodernism projects a temporal hierarchy, which in turn maps onto a spatially differentiated modernity, a Wallersteinian world-system structured around cultural centers and peripheries, even when the positions in this hierarchy are, as in Olson’s and Jameson’s uses of postmodernism, partly inverted.

Term

Just like modernism, postmodernism has been put to very different uses in different places, times, and languages. These uses of postmodernism have taken place not in isolation but in the context of uneven cultural capital. The diverse uses of the term postmodernism in, say, the United States, New Zealand, China, and Russia are inseparable from claims for attention and centrality within a context of a global cultural power imbalance. Yet as with modernism, alongside “often brutal inequities of power,” these uses of postmodernism involve “global weblike formations, with many multidirectional links” (Friedman, “Periodizing Modernism” 435). Like modernism, therefore, postmodernism requires “a polycentric approach” that recognizes how each use of postmodernism “is constructed through engagement” with other uses of the term and in turn shapes those other uses (Friedman, “Periodizing Modernism” 438).

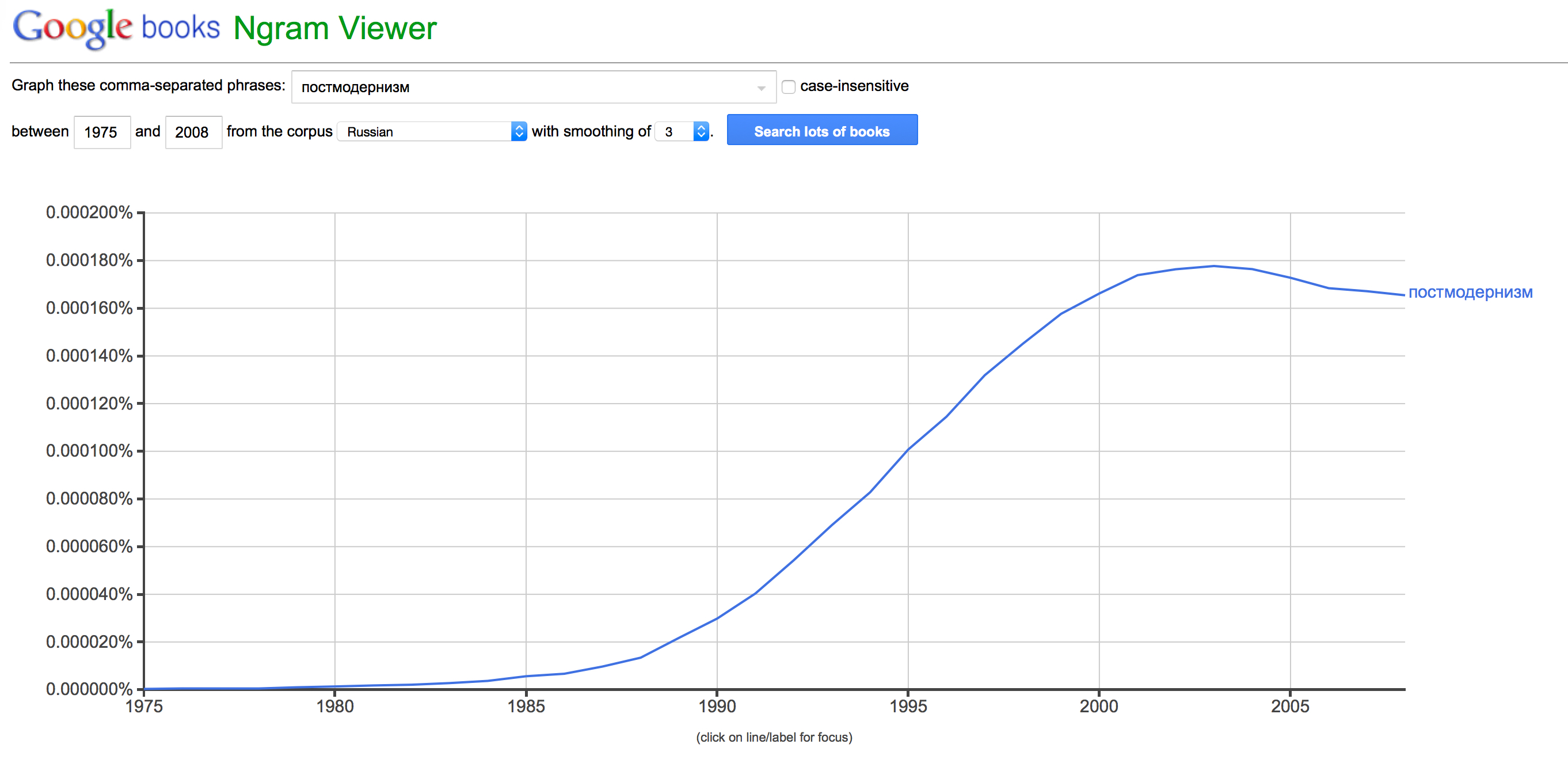

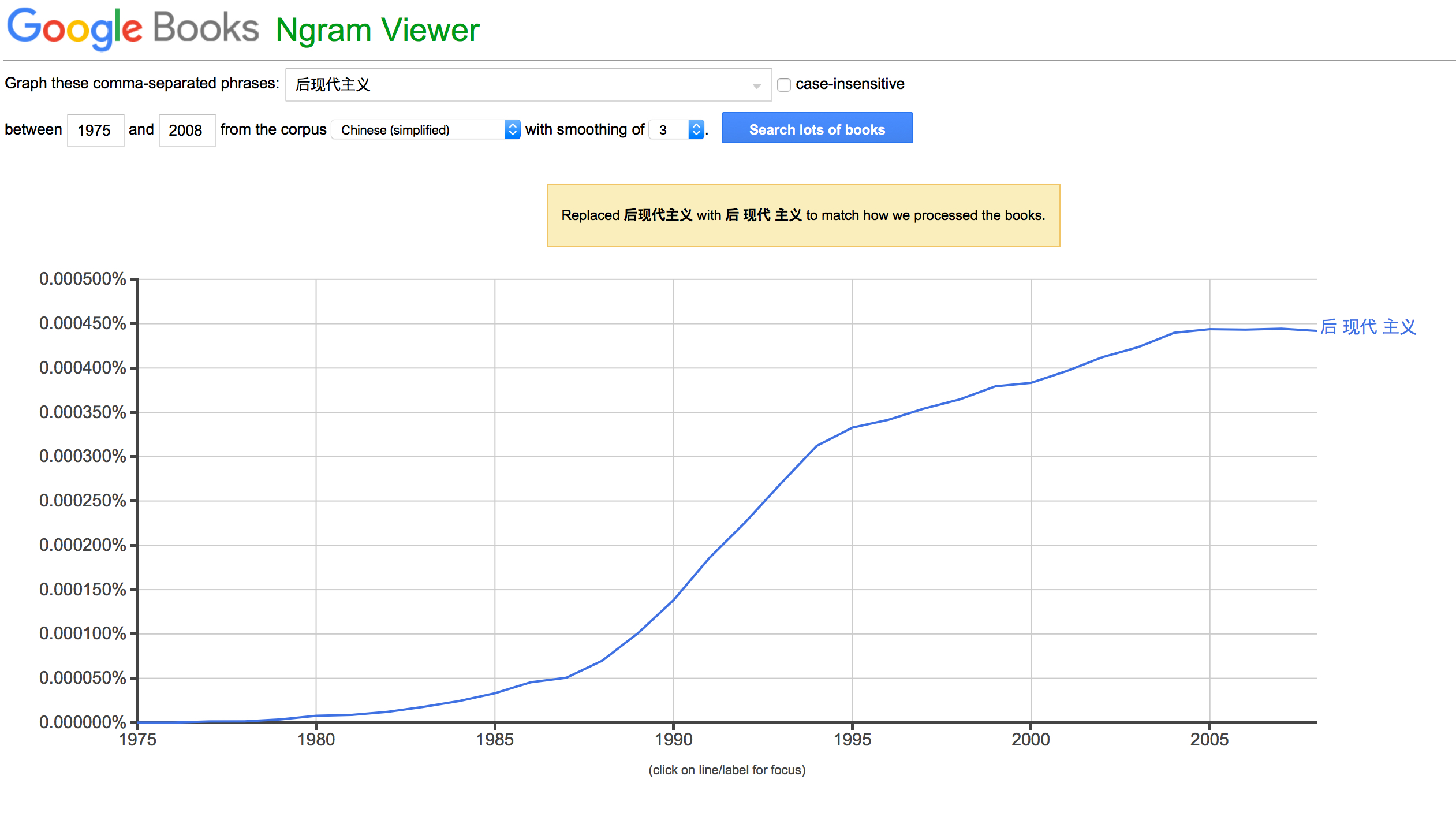

At first glance, tracing the uses of the term postmodernism would seem only to reinforce a temporally and spatially hierarchical structure of origins in the United States in the 1970s, followed by development in Western Europe in the late 1970s and 1980s, before the term is adopted in more peripheral regions of the world literary-system in the late 1980s and 1990s. Indeed, the various Google Books n-grams of the term’s use visualize waves of influence extending outwards from the Anglo-American center, with the peak in the crest rising and falling later in such semi-peripheries as Russia and China (compare figs. 1, 2, and 3). Postmodernism, then, would seem to be the perfect example of a wave-like process of global literary influence and change, as proposed by Franco Moretti in relation to the worldwide spread of the novel.

fig 1 postmodernism in English.jpg (large version in separate window)

fig 1 postmodernism in English.jpg (large version in separate window)

fig 2 postmodernism in Russian.jpg (large version in separate window)

fig 2 postmodernism in Russian.jpg (large version in separate window)

fig 3 postmodernism in Chinese.jpg (large version in separate window)

fig 3 postmodernism in Chinese.jpg (large version in separate window)

Figures 1–3 use Google Books Ngram corpuses to compare the changes between 1975 and 2008 in the word frequency of the term postmodernism in English (fig. 1) and its cognates in Russian (fig. 2) and simplified Chinese (fig. 3).

Although the spread in the use of postmodernism is in part the history of a global form inflected by local circumstances, the developing uses of the term also involve multidirectional pathways of influence and counterinfluence and of cross-cultural encounter and exchange that are obscured by a model of innovation in cultural centers spreading out in waves to the peripheries of the cultural world-system. As with Olson’s and Jameson’s appeals to China, other uses of postmodernism in the United States, New Zealand, Russia, and China tell a more complex story of contested cultural centers and transnational affiliations.

United States

The canonical history of postmodernism’s use in US literary studies is well known. In their groundbreaking articles, published in 1971 and 1972 respectively, Ihab Hassan and David Antin used the term postmodernism to describe some of the new kinds of literary and cultural production that had emerged in the 1950s and 1960s, with Antin singling out Olson’s precursor role in the postmodern revival of radical modernism. (Neither author, though, notes the independent Spanish-language usage of the term, which dates from the 1930s; Anderson 4.) The propagation of the term within US literary studies in the early 1970s made it available for Jean-François Lyotard, who visited Milwaukee as a guest of Hassan in 1976, three years prior to the publication of La Condition Postmoderne (1979) (Anderson 24). Though arguably never central to French poststructuralist thought, postmodernism became for a time “the main reading perspective for French theory in the United States” thanks to Lyotard’s use of the term just at the point when French theory was gaining increasing attention within the US academy (Cusset 215). Lyotard’s encounter with US literary theory then led to the transformation of the term in the United States from a synonym for the mid-century avant-garde practices of Olson, John Cage, and others, to shorthand for the new influx of French theory. Rather than postmodernism’s uses extending waves of influence outwards from a cultural center, the uses of postmodernism here involved exchange and contestation over cultural centrality.

Already in 1993, Perloff had begun to examine this history of the term’s use in the context of US literary studies. She argued that in the 1970s and earlier (going back to Olson’s use of the term) “postmodern” represents “everything that is radical, innovative, forward-looking” in literary and artistic practice (“Postmodernism” 163). According to Perloff, Lyotard’s The Postmodern Condition marks the “shift…to the broader cultural definition of the term” (“Postmodernism” 166). Perloff traces a shift from the “utopian” use of the term in the 1970s to a more dystopian use in the 1980s and 1990s (“Postmodernism” 165). This dystopian turn occurred largely through the influence of Jameson’s essay then book Postmodernism; or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, which successfully harnessed and propelled the rise in the term’s popularity in the late 1980s and 1990s.

Perloff herself uses the term postmodernism and the history of its application in US literary studies to wage her ongoing war for what she calls “literary criticism” and against “cultural critique.” In a revised version of the same essay, she contrasts literary criticism with the cultural critique of “theoretical polemics, especially with regard to postcolonialism, race, and gender” (Poetry on and off the Page 32). In other words, her account of postmodernism is a cautionary tale about artistic innovation swamped by French philosophy, Marxist cultural theory, and identity politics. By recovering an earlier use of postmodernism, Perloff seeks to oppose literature and literary criticism to theory and politics. While acknowledging the importance of periodization (she notes the significant differences between poetry in the 1960-70s and the 1980-90s), Perloff also wants to separate postmodernist cultural production from larger historical changes - just the kind of separation that Jameson’s essay had sought to collapse.

Perry Anderson’s study a few years later expands on Perloff’s account of the developing uses of the term. Anderson, of course, uses this history of postmodernism to quite different political ends, but he, too, turns to Olson to prise the term free from Jameson’s dystopic analysis and writes with a similar awareness of the cross-cultural encounters that produced the term’s diverse and even contrary history of uses. Owing to this history, by the mid-1980s postmodernism was already available as a figure for radical artistic experimentation, for French theoretical sophistication, and for postindustrial capitalism and global neoliberalism. These uses would be subject to further remixing and remaking as the term was adopted and adapted elsewhere in the world.

New Zealand

In mid-1980s New Zealand, Ian Wedde attempted to redraw the map of local poetry partly under the sign of postmodernism. Wedde was given the opportunity to edit a new Penguin Book of New Zealand Verse, the first major new edition since the 1960 Penguin Book of New Zealand Verse, edited by Allen Curnow, which had served to establish a canon of New Zealand poetry that embodied Curnow’s critical nationalist and modernist vision. Wedde’s introduction to the 1985 edition was a landmark document in New Zealand literary history. In the introduction, Wedde explicitly invokes “the linguistic republic of postmodernist words,” connecting postmodernism to the “post-1960” and “post-Baxter” (in reference to the poet James K. Baxter) opposition to the brand of modernism canonized in Curnow’s anthology (24, 44).

Wedde’s use of postmodernism reflects New Zealand’s mid-1980s moment of “decolonization,” marked by the 1984 election of the fourth Labour government and the anti-nuclear legislation passed by that government three years later (Belich). Wedde connected postmodernism to the effort to think about language in relation to location: “the historical process towards the sense of consummation in location that comes…with a poem like David Eggleton’s ‘Painting Mount Taranaki’ is also a development towards a sense of culture that is internally familiar” (39). “Consummation in location” involved for Wedde - as for many New Zealand poets of the 1960s and 1970s - an emphasis on the vernacular spoken word that derived from the New American Poetry canonized in Donald Allen’s eponymous 1960 anthology. This anthology included the work of Robert Creeley, who had visited New Zealand in 1976, and Olson, whom Wedde cites in his introduction. Referring to the “postmodern American poetry” of Olson and Edward Dorn, Wedde associates postmodernism with a turn to “the demotic” and process-oriented poetics of the mid-twentieth-century American avant-garde (28-29).

Wedde appealed to the same mid-century American avant-garde that Antin had presented under the label “postmodern” in the pages of boundary 2 in the early 1970s. Yet by the time Wedde’s appeal appeared in 1985, postmodernism had different, contradictory uses in the United States. The emphasis on speech in the New American Poetry was under severe attack from various parts of the American poetry avant-garde - perhaps most prominently from Language writing, as canonized under the sign of Robert Grenier’s 1971 slogan “I HATE SPEECH.” This shift in the literary field of avant-garde American poetry was reflected in the use of the term postmodernism. It was not Olson’s or Wedde’s “demotic” poetry of location but the work of another Language writer, Bob Perelman, that in 1984 Jameson cited as exemplary of the fragmented subject of postmodernism.

These contrary uses of postmodernism were reflected in the New Zealand literary field. Although published in the same year in the same country, Wedde’s account of postmodernism seems diametrically opposed to those put forward by Leonard Wilcox and Simon During in the New Zealand literary journal Landfall, another venerable institution of Curnow’s brand of nationalist modernism. Wilcox distinguishes between the Olson-inflected, “pastoral” understanding of postmodernism––dominant in New Zealand and conducive to the country’s “preoccupation with defining a national identity”––and “those features which theorists have come to see as salient characteristics of postmodernism,” such as a “new depthlessness and a whole new culture of the image and the simulacrum” (344-46). Wilcox cites especially Lyotard and Jameson, repeating the latter’s account of the “‘schizophrenic’ utterances of the so-called Language poetry or New Sentence school of San Francisco” (345).

Whereas Wedde uses postmodernism to promote a demotic style that emphasizes “location,…not just in terms of place, but in the fullest cultural sense,” for During, “the postmodern subject no longer lives in surroundings where objects are invested with, and bring forth, organised memories and feelings” (Wedde 26; During, “Postmodernism or Postcolonialism” 368). Instead, Wedde’s postmodernism resembles Wilcox’s “post-provincialism”––the “cultural nationalist equivalent of postmodernism in New Zealand”––and During’s “postcolonialism,” defined as the “need for an identity granted not in terms of the colonial power, but in terms of themselves” (Wilcox 355; During, “Postmodernism or Postcolonialism” 369). Wilcox and During use postmodernism to attack such naïvely representative notions of national literature, even as they write with an awareness of the equal danger of an utterly dislocated postmodern cultural logic, the dystopian vision sketched by Jameson the previous year and cited by both authors.

Wedde, Wilcox, and During extend different parts of the argument put forward by Roger Horrocks a couple of years earlier in his 1983 essay “The Invention of New Zealand.” Like Wedde, Horrocks questions the rhetoric of the 1960 Penguin Book of New Zealand Verse and Curnow’s nationalist modernism. But Horrocks also seems to anticipate During’s argument that “representations which claim to reflect, or intend to produce, a distinctively postcolonial reality” are in fact “already postmodern images” (“Postmodernism or Postcolonialism” 372). While the term postmodern scarcely appears in Horrocks’s essay, like During, Horrocks emphasizes the “invention” of a national “reality” and a national literature.

These local cultural battles, as in the United States, involved a network of relations and affiliations that extended beyond the boundary of the nation. Wilcox had completed his PhD at the University of California, Irvine, in 1976, and so brought to New Zealand his knowledge of North American theory along with a sense of his new home’s provinciality. Though his essay ends by suggesting the ability of New Zealand postmodernism to engage “the crisis of authority vested in Western European culture and its ‘master narratives,’” Wilcox reinforces the spatial and temporal hierarchies that attend periodization (361). He clings to the authority of Euro-American theorists such as Lyotard and Jameson in criticizing the anachronistic use of the term postmodernism in New Zealand. For Wilcox, New Zealand’s anachronistic use of postmodernism reflects the country’s “cultural lag” and the fact that it “is not properly a consumer society” (351: 348).

When During published his essay on postmodernism in the New Zealand literary journal Landfall, he was teaching at the University of Melbourne, an experience that presumably prompted his comparison between the “postcolonised discourse” of New Zealand and the “import rhetoric” with which he characterized Australia’s embrace of French theory (“Postmodernism or Postcolonialism” 371). This geographical contrast echoes During’s own interweaving of postcolonial and postmodern discourse through which he positions himself simultaneously within a national literary conversation and the international networks of the burgeoning field of literary theory.

During extends his negotiation of these overlapping cultural fields in the internationalized version of his essay published two years later as “Postmodernism or Post-Colonialism Today,” in which During replaces the local cultural references to Janet Frame and Keri Hulme with names carrying more currency in the global cultural marketplace: Joseph Conrad, Francis Coppola, and Salman Rushdie. While During explicitly seeks “to problematise” both postcolonial and postmodern discourse, his turn to theory to do so and the essay’s publication history evince its absorption into “the larger international cultural economy” that During associates with postmodernism (“Postmodernism or Postcolonialism” 380, 372).

During’s use of postmodernism is not only an example of how the term spread outwards from the cultural centers of North America and Western Europe; it also illustrates the competing available meanings of postmodernism that were being deployed and transformed in local cultural battles and that were in turn, via During’s later essay, transmitted (albeit in muted form) back to the cultural center. In other words, it is not only the unequal power of centers and peripheries within the cultural world-system but also networks of cross-cultural encounters and negotiations that collectively produce the uses of postmodernism.

Russia

Postmodernism retrospectively provided one term for Russian literature and art of the 1970s and 1980s that rejected the conventions of both official and unofficial culture. In the 1990s, theorists such as Mikhail Epstein and Viacheslav Kuritsyn sought to describe new tendencies in late-Soviet art, such as Russian conceptualism and “metarealism,” as postmodern. Writing in the mid-1990s, Boris Ivanov described the new literary experimentalism associated with the late samizdat Mitin zhurnal, which began publishing in the mid-1980s: “anyone who wants to properly understand what went on in literature in the second half of the 1980s and who wants a clear idea of how Soviet postmodernism began should be acquainted with this publication” (Ivanov 195). Yet a brief survey of content from the early issues of Mitin zhurnal reveals that postmodernism was not a key term at the time.

Epstein also retrospectively associated postmodernism with Russian literature of the 1970s and 1980s, arguing that “corresponding movements and their programs arose in Russian letters before the Western model and terminology were applied to them” (Postmodern v Rossii 106). Epstein presents this postmodernist literature as anticipating the collapse of the Soviet Union by connecting the term postmodernism to post-communism and what he terms “post-futurism”: “The ‘communist future’ has become a thing of the past, while the feudal and bourgeois ‘past’ approaches us from the direction where we had expected to meet the future” (After the Future xi). In other words, Epstein uses postmodernism both to canonize a late-Soviet literature as the new literature of post-Soviet Russia and, at the same time - in a game with a long pedigree in Russia (e.g., Russian futurism and conceptualism) - to claim priority for a Russian version of a new idea apparently originating elsewhere.

Similarly, Boris Groys, in his influential book The Total Art of Stalinism, describes a postmodern art that he claims looks like but differs from Western postmodernism. Where in the West, appropriation is still carried out in the name of “purity and independence”; in Russia, the “complete triumph of modernism dispelled all illusions of purity and impeccability” (11). So that “In the Soviet politician aspiring to transform the world…, the artist inevitably recognizes his alter ego,…and finds that his own inspiration and the callousness of power share some common roots” (12). I am not sure how far this really is from Andy Warhol or from the cynicism of contemporary US conceptual writers such as Vanessa Place and Kenneth Goldsmith. But the point is that here, as elsewhere in the world, theorists like Groys use the term postmodernism both to historicize and to play a game of differentiation and competition with the West.

In the early 1990s, US writers and critics also partook in this competitive dialogue over the ownership of postmodernism. In a forum on Russian postmodernism, Perloff and Barrett Watten differentiated Western postmodernism from its inauthentic non-Western counterpart, rejecting Epstein’s argument that “the postmodern condition is essentially the same in the East and West, although it proceeds from opposite foundations: ideology and economics, respectively” (“Draft Essay”). Instead, Watten and Perloff echoed the them/us structure of Cold War rhetoric in their insistence that Western “postmodernism” and the new Russian literature were incommensurate: “identifying these…developments with postmodernism would be to misunderstand them,” and therefore “Russian Postmodernism” is an “oxymoron” (Watten; Perloff, “Russian Postmodernism”).

Despite these objections, the term postmodernism in Russia came to name a real and important critique of modernist and avant-garde art of the early twentieth century, especially the early Soviet avant-garde work of artists such as Alexander Rodchenko, who was celebrated in the West by writers and artists associated with postmodernism. While theorists like Groys in a sense built on Jameson’s critical analysis of the postmodern, this Russian critique is in fact more thoroughgoing. It is not just that art has lost its ability to be critical when fragmentation becomes a cultural dominant, but, for Groys, modernism was never critical, never alienated at all, but part of a cultural logic that ends in Stalinism. By triangulating Western accounts of modernism and postmodernism through the Soviet context, Groys inverted Jameson’s contrast between modernist critique and postmodernist complicity. Groys thereby also implicitly questioned Antin’s and Perloff’s use of postmodernism to champion the revival of radical modernism. In Russia, postmodernism was not just adopted and adapted, but transformed.

China

The uptake of the term postmodernism (houxiandaizhuyi 后现代主义) in Mainland China is generally dated to Jameson’s 1985 visit to Peking University, where he taught during the autumn semester. Jameson’s subsequently published lectures became “the most widely read and quoted work in Chinese discussions of postmodernism” (Dirlik and Zhang 1n1). Yet the history of postmodernism in China is not merely one of influence and uptake but also one of local transformation. Postmodernism arrived in China at the height of a contentious revival of the term modernism to refer to works outside the previous restrictive norms of official literature and to associate this new work with officially endorsed modernization. The term postmodernism therefore came to refer to Chinese culture after the exile or censoring of many prominent Chinese modernists following the government crackdown of June 4, 1989, and postmodernity to the era after Deng Xiaoping’s further boost to market reforms in 1992.

Postmodernism was used in China to name the rejection not just of the utopian Chinese modernism of the 1980s but also of the drive toward the so-called fifth modernization of democracy. Thus Zhang Yiwu could write of the “post-new period” of the 1990s as the “total surpassing of the ‘modernity’ sought by ‘new period’ culture from the late 1970s onward” (Saussy 132). Like Zhang Yiwu, Zhang Xudong attended Jameson’s lectures while studying at Peking University, and he later traveled to the United States to study under Jameson. Zhang Xudong also came to contrast postmodernism with 1980s modernization and with a revival of modernist literature in China during that decade that, according to Zhang, “valorized the political illusions of searching for a lost, immanent social value” (“Epilogue” 400; Chinese Modernism 122). Zhang Xudong argued that in 1980s China “meta-narratives” were still in effect, whereas the “post-Enlightenment” period of the 1990s brought “a revolt against the modernist and modernization ideology of the New Era (1979-89); during this time modernism posed as a ‘new enlightenment’ in opposition to Maoism…and thus sealed the legitimacy of Deng’s China within the discourse of modernity” (“Epilogue” 400). Whatever its intention, Zhang Xudong’s analysis of the “vacuous metaphysics” of 1980s Chinese artistic experimentation in effect celebrated the giving up of such naive “political illusions” as democracy in favor of the possibilities of the marketplace and the unquestioned power of the Communist Party (Chinese Modernism 142, 122). As Haun Saussy noted wryly in the early 2000s, “Under contemporary Chinese conditions, postmodernity’s antipathy to universals together with its inability to formulate a principled pluralism gives it the specific contours of an official-thought-in-waiting” (132). Thus in China, “postmodernism” and other “posts” (houxue 后学) came to be used by some Chinese theorists (and by Western philosophers such as Roger Ames and David Hill) to justify national chauvinism and to attack demands for human rights and democracy through arguments about cultural relativism.

Yet despite the alleged opposition between 1980s universalists and 1990s relativists, the discourse of modernity in the 1980s and of postmodernity in the 1990s shared a commitment to the ideological imperative of catching up with the West. As in Russia, in China to claim postmodernism for oneself was both to accept and to attempt to overcome the spatial hierarchy embedded in the term’s periodizing function.

Ends

We might date the death of postmodernism as a term that is used, rather than merely mentioned, in literary studies in English to around the year 2000. Its demise is marked, for instance, by the publication of Susan Stanford Friedman’s “Definitional Excursions: The Meanings of Modern/Modernity/Modernism” in 2001 and Marjorie Perloff’s 21st-Century Modernism the following year. Both Friedman and Perloff articulate and contribute to the turn away from postmodernism in the Anglo-American academy and both do so through an expanded account of modernism. Friedman and Perloff argue that modernism encompasses everything supposedly associated with postmodernism, including the “embrace of chaos…the crisis of representation, fragmentation, alienation…indeterminacy, the rupture of certainty - material and symbolic” (Friedman, “Definitional Excursions” 494). A few years later, in attempting to make the case for the term’s ongoing usefulness, Brian McHale would nevertheless accept this understanding of postmodernism - already present in Hassan’s and Antin’s essays from the early 1970s - as merely another form of modernism: “‘postmodernism’ signifies the full range of possibilities…available before a normalizing modernism had made its choices, and which became available again after normalized modernism had run its course” (x).

As the titles of these works by Friedman and Perloff suggest, the decline of interest in the postmodern in the early 2000s was matched by the rise of what Douglas Mao and Rebecca Walkowitz dubbed the “new modernist studies.” The new modernist studies offered an expanded sense of modernism that appeared to render postmodernism irrelevant. Why do we need postmodernism when we can just as easily call it twenty-first-century modernism, as Perloff asked over a decade ago?

My proposal to reexamine the uses of postmodernism in literature and literary studies draws on the kind of historicizing and comparative work that has made modernist studies such a dynamic field over the past couple of decades. These historicizing and comparative approaches suggest that postmodernism deserves a place in any literary and cultural history of the last seventy years.

Seen historically and comparatively, postmodernism is the sum of its uses or misuses. One might argue that these uses bear an underlying common conceptual form - a wave that is diffracted as the concept passes through different places and cultural conditions at different times and is inflected by local contexts. But this would be to accept too easily the constraining habits of periodization: the center-periphery model of originality and belatedness through which postmodernism itself was frequently imagined. Amongst other things, such a model posits the existence of a relatively stable wave of meaning that undergoes change as it passes through various cultural contexts. When we consider the widely various uses of postmodernism even in the small sampling surveyed here, no such stability exists.

Nevertheless, some common threads emerge in the uses of postmodernism. First and most obviously, postmodernism was used to attack diverse versions of modernism. Second, postmodernism was used negatively as a proxy term for globalization. Third and somewhat contradictorily, postmodernism was used positively as a term to mark a work’s, a country’s, or, and especially, a theorist’s up-to-date position vis-à-vis the global literary and cultural marketplace. Postmodernism was a term through which one could assert theoretical sophistication in the period of literary theory’s ascendance and the up-to-date-ness of the literary culture of an individual or country.

These contrary uses - along with postmodernism’s association with anti-universalism - enabled the term to embody both sides in the unfolding tension between globalization and localism. Postmodernism could be used to claim an advanced position in the global cultural field and to dismiss nationalisms and other localisms as hopelessly theoretically naive or outdated. Yet it could also be deployed to assert cultural relativism and so the singularity of a national or local culture.

The story of postmodernism’s uses describes no coherent theory or period but rather illuminates the struggle to come to grips with changes both local and global in the final decades of the twentieth century. While postmodernism might indeed be useless as a theoretical concept or periodization, it remains a key term in the history of twentieth-century thought.

Works Cited

Anderson, Perry. Origins of Postmodernity. London: Verso, 1998. Print.

Antin, David. “Modernism and Postmodernism: Approaching the Present in American Poetry.” boundary 2 1.1 (1972): 98-133. Print.

Belich, James. Paradise Reforged: A History of the New Zealanders from the 1880s to the Year 2000. Auckland: Allen Lane; Penguin, 2001. Print.

Butterick, George F. “Charles Olson and the Postmodern Advance.” The Iowa Review 11.4 (1980): 3-27. Web. 14 March 2016.

Cusset, François. French Theory: How Foucault, Derrida, Deleuze, & Co. Transformed the Intellectual Life of the United States. Trans. Jeff Fort. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 2008. Print.

Dirlik, Arif, and Xudong Zhang. “Introduction: Postmodernism and China.” Postmodernism and China. Spec. issue of boundary 2 24.3 (1997): 1-18. Print.

During, Simon. “Postmodernism or Postcolonialism?” Landfall 155 (September 1985): 366-80. Print.

---. “Postmodernism or Post-Colonialism Today.” Textual Practice 1.1 (1987): 32-47. Print.

Dworkin, Craig. “Seja Marginal.” The Consequence of Innovation: 21st Century Poetics. Ed. Craig Dworkin. New York: Roof, 2008. 7-24. Print.

Epstein, Mikhail. After the Future: The Paradoxes of Postmodernism and Contemporary Russian Culture. Trans. Anesa Miller-Pogacar. Amherst: U of Massachusetts P, 1995. Print.

---. “A Draft Essay on Russian and Western Postmodernism.” Postmodern Culture 3.2 (1993): n. pag. Web. 14 March 2016.

---. Postmodern v Rossii: Literatura i teoriia. Moscow: Izdanie R. Elinina, 2000. Print.

Friedman, Susan Stanford. “Definitional Excursions: The Meanings of Modern/Modernity/Modernism.” Modernism/Modernity 8.3 (2001): 493-513. Print.

---. “Periodizing Modernism: Postcolonial Modernities and the Space/Time Borders of Modernist Studies.” Modernism/Modernity 13.3 (2006): 425-43. Print.

Grenier, Robert. “On Speech.” This 1 (1971): n. pag. Print.

Groys, Boris. The Total Art of Stalinism: Avant-Garde, Aesthetic Dictatorship, and Beyond. Trans. Charles Rougle. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1992. Print.

Hassan, Ihab. “Modernism and Postmodernism: Inquiries, Reflections, and Speculations.” New Literary History 3.1 (1971): 5-30. Print.

Hayot, Eric. “Against Periodization; or, On Institutional Time.” New Literary History 42.4 (2011): 739-56. Print.

Horrocks, Roger. “The Invention of New Zealand.” And 1 (1983): n. pag. Print.

Ivanov, Boris I. “V bytnost’ Peterburga Leningradom: O leningradskom samizdate.” Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie 14 (1995): 188-99. Print.

Jakobson, Roman. Interview with David Shapiro. 1979. Sulfur 12 (1985): 165-71. Print.

Jameson, Fredric. “Postmodernism; or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism.” New Left Review 146 (1984): 53-92. Print.

Kuritsyn, Viacheslav. Russkii literaturnyi postmodernizm. Moscow: OGI, 2000. Print.

Liu, Alan. Laws of the Cool: Knowledge Work and the Culture of Information. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2004. Print.

McHale, Brian. The Obligation toward the Difficult Whole: Postmodernist Long Poems. Tuscaloosa: U of Alabama P, 2004. Print.

Mao, Douglas, and Rebecca L. Walkowitz. “The New Modernist Studies.” PMLA 123.3 (2008): 737-48. Print.

Modernist Studies Association. Homepage. Web. 14 March 2016.

Moretti, Franco. “Conjectures on World Literature.” New Left Review 1 (2000): 54-68. Print.

Perloff, Marjorie. 21st-Century Modernism: The “New” Poetics. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2002. Print.

---. Poetry on and off the Page: Essays for Emergent Occasions. Evanston, IL: Northwestern UP, 1998. Print.

---. “Postmodernism / Fin de Siècle: The Prospects for Openness in a Decade of Closure.” Criticism 35.2 (1993): 161-92. Print.

---. “Russian Postmodernism: An Oxymoron?” Postmodern Culture 3.2 (1993): n. pag. Web. 14 March 2016.

Saussy, Haun. Great Walls of Discourse and Other Adventures in Cultural China. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 2001. Print.

Watten, Barrett. “Post-Soviet Subjectivity in Arkadii Dragomoshchenko and Ilya Kabakov.” Postmodern Culture 3.2 (1993): n. pag. Web. 14 March 2016.

Wedde, Ian. “Introduction.” The Penguin Book of New Zealand Verse. Ed. Ian Wedde and Harvey McQueen. Auckland: Penguin, 1985. 23-52. Print.

Wilcox, Leonard. “Postmodernism or Anti-modernism?” Landfall 155 (September 1985): 344-64. Print.

Zhang Xudong. Chinese Modernism in the Era of Reforms: Cultural Fever, Avantgarde Fiction, and the New Chinese Cinema. Durham, NC: Duke UP, 1997. Print.

---. “Epilogue: Postmodernism and Postsocialist Society - Historicizing the Present.” Postmodernism and China. Ed. Arif Dirlik and Xudong Zhang. Durham, NC: Duke UP, 2000. 399-442. Print.

Cite this essay

Edmond, Jacob. "The Uses of Postmodernism" Electronic Book Review, 4 December 2016, https://electronicbookreview.com/publications/the-uses-of-postmodernism/