Video Games Go to Washington: The Story Behind The Howard Dean for Iowa Game

Ian Bogost and Gonzalo Frasca explain a new genre: persuasive games, and delve into the development and emerging legacy of The Howard Dean for Iowa Game, "the first official video game ever commissioned in the history of U.S. presidential elections." This new genre provides an opportunity to rethink the cultural status of games. If games are normally judged by how entertaining they are, persuasive games must be released from this criterion and assessed on how well they convey their message.

On December 16, 2003, popular Web magazine Slate published an article by journalist and author Steven Johnson (2003). Reviewing simulation games that engage problems of social organization, Johnson posed a question: “The [2004] U.S. presidential campaign may be the first true election of the digital age, but it’s still missing one key ingredient. Where is the video-game version of Campaign 2004?” Upon reading this article, we smiled at its perfect timing: at that very moment we were developing The Howard Dean for Iowa Game, the first official video game ever commissioned in the history of U.S. Presidential elections.

Former Vermont governor Howard Dean failed miserably in his bid to become the 2004 Democratic U.S. presidential candidate. Still, he was incredibly successful in changing the way political campaigns of all types are carried out. Dean supporters made extensive use of new media tools such as e-mail, Web sites, and blogs to foster support from the grassroots. Howard Dean was also the first candidate to use a video game as endorsed political speech.

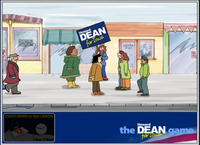

The Dean game was launched during Christmas week 2003. Players were able to play it for free on the candidate’s web page. It was very successful in terms of audience: it reached 100,000 plays in the month before the Iowa caucus, a very respectable number considering its novelty and the fact that it was launched during the holidays.

Designing the game was quite a challenge. Even though we both were experienced game developers, nobody had tried anything like this before. The web was plagued with satirical amateur Flash games, but we faced many difficult questions: how do we tailor a video game to convey an endorsed political message? How do we craft it so the public does not dismiss it as trivial? How does it integrate with the rest of the campaign? This article reviews the design and production process behind The Howard Dean for Iowa Game. It also locates itself within the context of the games that followed it on both sides of the political fence.

Virtual Campaigning

The game was conceived in concert with strategists from the campaign, a process that took place just before the important primary season of the Presidential election. For the benefit of our international readers, in the United States, a primary is a preliminary election in which voters with an affiliation to a particular party (Democrat or Republican) vote to nominate a candidate to run in the general election. Like the electoral college, primaries are often criticized for conflating local, regional, and national issues. In American elections, the first primaries are held in the small states of Iowa and New Hampshire, and media attention surrounding these early events often impacts the results of primaries in other states, held over a six-month period. After considering several possible designs (see below: The Other Dean Game), the campaign commissioned a game about grassroots outreach, the core principle behind Dean’s unique election strategy. The intention of the game was to teach current and potential constituents about the power of grassroots outreach. The campaign was not interested in speaking to their political opponents through the game; rather, they hoped to muster commitment from “fence-sitter supporters,” those citizens who were sympathetic to the candidate but who had not yet consummated that sympathy with material support, in the form of contributions, local participation, or simply firm commitment to cast a Dean vote in their state primary. The game had two goals: first, to model and illustrate the logic of grassroots outreach and argue for its primacy as a populist political strategy. Second, to model the actual activities of grassroots outreach to help fence-sitters understand how they could contribute in a concrete way.

Since one of the game’s primary goals was to teach current and potential constituents about the power of grassroots outreach, we needed to build a simulation model for supporter growth over time. To play the game, players placed virtual supporters on a map of Iowa, playing one of the three outreach minigames to set the effectiveness of their virtual supporters.

Caption: Sketch and final map.

This effectiveness was based on the player’s performance in each minigame; a better score meant a more efficient supporter. Because supporters could not be “reset” once placed, this encouraged players to perform their best each time they played a minigame. After having set the effectiveness of a supporter through one of the minigames, that supporter worked nonstop, enacting “virtual outreach” to win over other virtual Iowans. In the main map screen, more effective virtual supporters worked more quickly in their region; a circular gauge showed their progress. When the gauge filled, a new supporter spawned, ready for the player to place for additional outreach.

To help illustrate the multiplicative effect of grassroots support, multiple supporters in the same region would work together, speeding up the outreach process. The virtual supporters worked together to generate even more support absent the player’s direct action, simulating the campaign’s argument that grassroots outreach would allow Dean to muster meaningful bottom-up support from individual voters rather than seeking top-down support. Game time counted down to the date of the Iowa Caucus, the first major event in the formal race for U.S. president. When caucus time came, the game ended and players saw how many virtual supporters they had recruited. The game hooked in to the rest of the Dean campaign’s online initiatives, offering pathways to candidate information, channels for contribution, and additional resources.

Development Time as an Expressive Constraint

Like all media, video games are often structured by the constraints under which they can be created. Most frequently, we talk about the material constraints of games. Limited processing power in early consoles, arcade games, and modern mobile phones offer one such example. The visual acuity possible on Xbox 360 and Atari 2600 alike are materially constrained by the graphic output technologies available on those respective devices. Constrained authorship has served as both a limitation and a catalyst for creativity since antiquity. Early Greek and Latin poetry relies on strict meter both to structure lyric and to facilitate recollection for oratory performance. From the classicist ideal of Pound and Eliot to Georges Perec’s lipgrammatic novel La Disparition (Perec 1969), which was composed without using the letter e, artists often impose constraints on themselves as part of a broader vision.

But less frequently do we acknowledge the role of time as a constraint in artistic expression. Certain surrealist writing games were designed to be executed in a single sitting, and improvisational acting relies entirely on the immediacy of performance as its grounding aesthetic. But video games are usually not considered to be a medium of temporally constrained authorship. In the gaming news and even in the popular media, we hear more and more about the rising costs of video game production: teams of several hundred working for several years on the largest projects. Of course, not all developers have access to such bottomless resources, and independent games are usually produced on shoestring budgets and during off-hours.

Another example of the use of time as a constraint comes from “minigames” such as those in the several WarioWare We love WarioWare and consider it a major inspiration for the design in this and other games we have created. collections for the Nintendo Game Boy and DS.

These titles offer hundreds of extremely small games, each of which is played in a matter of seconds. In one game, the player times a button press to catch a falling straw; in another, the player must quickly locate a burglar by moving a spotlight around the screen. These games use time as a way to constrain and structure player action.

But another type of temporal structure constrains many games: the pace of the business and social context in which the game will be released and played. For better or worse, film-licensed games are subjected to this constraint more than most other commercial games, as film studios and publishers strive to leverage the enormous cross-marketing a film release provides to a game, and vice versa. As game developers who have spent a good portion of our respective careers creating games commissioned by professional organizations like consumer products companies, advertising agencies, broadcast networks, and film studios, we are accustomed to challenging - even irrational - development timeframes. Doing work-for-hire at the behest of organizations that neither understand nor care about the schedules required to produce a quality game presents design challenges that many artists, academics, and even high-level professional developers might not acknowledge.

The Howard Dean for Iowa Game was created under such a constraint. Conceived in late November 2003, the time between the first conversations with the campaign and the launch of the game was just four weeks. The actual development time was only three weeks - and worse, the three weeks just before Christmas.

We bring up the constraint of time neither to solicit sympathy nor to use it as an excuse for the failings of the game. Rather, we want to suggest that the development process of endorsed games - those intended to align with broader external marketing and communication initiatives - introduces time as a fundamental constraint on expression, more so even than the demands of easy access on lower-end computers and low-bandwidth connections. “Crunch time” in AAA console and PC development usually refers to the period of similarly insane working hours in advance of a major milestone such as the Electronic Entertainment Expo (E3) trade show, a required testing release, or indeed a final ship date. We are not arguing that these developers have no experience with such crunches. However, we want to point out that in the case of endorsed games built for persuasion, the entire creative vision is structured by temporal constraints, from beginning to end.

In the case of the Dean game, limited time created numerous opportunities and limitations. For one thing, the game was intended to support the campaign’s broader focus on the Iowa Caucus, the first major event in the formal U.S. presidential election. The caucus takes place in the third week of January, and in order to be effective as a rhetorical tool, the game would have to be in the hands of potential supporters far enough in advance that, after playing, they could reflect on their experience and take action. The campaign hoped that new supporters would even consider traveling to Iowa to help campaign on the ground - a commitment that would require considerable planning and expense. Furthermore, the approaching Christmas and New Year’s holidays would assuredly distract supporters from the task at hand. This context, essentially one of consumer marketing, provided the most significant temporal constraint on the development process. In short, if we did not release the game before Christmas, it would risk serving no purpose whatsoever.

The rollout schedule subsequently constrained the quantity and quality of representation possible in the game itself. First we decided to separate the game’s two goals and develop them in parallel, as isolated components that would inform one another. This approach allowed us to muster two small, parallel groups, one working on the grassroots simulation and the other working on the individual outreach activities. Of the two, the second suffered more under the project’s time constraints. The grassroots simulation - what eventually became the Iowa map - would be a single system, a kind of lobby from which the player would access the various kinds of outreach activity. But the outreach activities themselves would each be different and thus require considerable individual care.

The question of what and how many outreach activities to include in the game was a matter of long discussion, both among ourselves and with the campaign itself. One of the primary goals for the game was to elucidate the concept of “grassroots outreach” - to give concrete examples of what it meant to perform such action. The logical conclusion was to represent as many such actions as possible in order to yield the broadest influence. Different activities might resonate more effectively with different players. Early on, we considered including as many such activities as possible, scaling down the representation of each by abstraction. But abstraction was precisely the problem the game hoped to solve - fence-sitter supporters were leery of getting involved in the campaign because they didn’t grasp what “involvement” really meant. It thus seemed foolish to sacrifice the concreteness of the outreach activities for the sake of quantity.

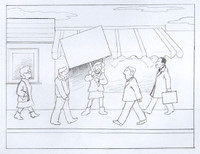

Instead, we decided to choose three outreach activities. We asked analysts at the campaign to identify the three most important, and they settled on sign-waving, door-to-door canvassing, and pamphleteering.

Caption: Sketch and final versions of sign-waving, door-to-door canvassing, and pamphleteering.

Later, campaign advisors would tell us that they probably should have chosen letter-writing as one of the three, since this was the main method the campaign had invoked as a means of getting national supporters involved in pre-caucus outreach without physically traveling to Iowa.

Each of the three minigames was individually hand-drawn, animated, and colored. This was a time-consuming process. We might even have been able to allocate time for more minigames by choosing a less graphically rich and laborious method for representing the outreach activities. But the goal of the game was to clarify these endeavors, not to obscure them further. Door-to-door canvassing could have been represented with small iconographic people like the ones we used on the main Iowa map display, but doing so would risk leaving the concept too abstract.

After outlining the overall concept, the strategists from the campaign itself allowed us a great deal of freedom during development. The medium in which we actually developed the game (Macromedia Flash) was chosen for its widespread availability among Internet users. While that platform’s architecture imposes constraints of its own, it affords and facilitates complex expression, given adequate time and resources. It may seem improbable to the average player, but time was the main creative constraint imposed upon the development of the game.

The Other Dean Game

We explored several design concepts with the Dean campaign before they settled on grassroots outreach as the core topic for a video game. Among the early designs was a game tentatively titled Call to Action. The game was intended to communicate a more mechanical, strategic message than did The Howard Dean for Iowa Game: Democrats need to focus their support, both votes and contributions, to Howard Dean in order to have a chance of combating Bush after the convention. Below is an excerpt from the initial game treatment for Call to Action. While this hypothetical game also does not deal explicitly with Dean’s policy positions, it might have advanced a strategic argument more unique to the candidate. However, the game’s design all but assumed that Dean’s reign would continue further into the primary season, an assumption that we now know would have been most unfortunately wrong.

You set the outcomes of the 2004 Presidential Primary season to position the Democratic Party for victory in the general election.

A U.S. map displays the primary schedule. At its right, you see the Political Power Meter, which measures the political force of each party. The Bush camp leads by 5,000 units - you need to take action in your community to rally support for the Democrats! You choose a set of assumptions about the primary season that matches your own - you believe that the Democrats must get behind one candidate early on to succeed. You choose your state, Iowa, to get started.

Your map swings out of view and a set of Power Bars display the political force of each Democratic candidate in the state’s primary or caucus, like a bar graph.

A clock begins to count down the number of days toward the primary - you have to act fast to rally support to the candidate of your choice. Beneath the power bars, you see members of the electorate, arranged in a labyrinth on the screen. You arrange and connect these voters, just like a real grassroots campaign would, to create a path for votes to get to your desired candidate (see Concept Art later). Experimenting, you create a path toward John Kerry. His Political Power bar rises and so does the Democratic Party’s on the Political Power Meter … but only by a little. Glancing at the time left until the primary, you start to worry. How can you make a difference at this pace?

As you experiment with the other candidates, you notice something. Adding support to Howard Dean seems to add more power to the party - and faster too. You learn that a vote for Dean doesn’t mean adding just one vote - it means adding a voter’s entire network of influence to the election’s most effective grassroots campaign. And you also learn that Dean supporters are more likely than other candidates to make multiple campaign contributions. You start guiding your state’s voters toward Dean, and the Democratic position on the Political Power Meter edges higher, faster.

As you move on to other primaries, you notice that when you shepherd voters toward Dean, his Political Power edges up even faster. By concentrating Democratic support in Dean’s campaign of grassroots influence, you’re building a viable political force to fight against Bush.

The initial game will only feature the Iowa caucus and New Hampshire primary. Additional primaries can be added into the game later. Once new primaries are available, those states will become selectable in the menu map. Positive performance on previous primaries affects performance on future primaries. States whose primary are ready to be played appear highlighted on the map. States whose primaries have passed cannot be played, but the map displays their results. At the beginning of the game, players can choose between about five different preset “assumptions” that represent different candidates’ positions or ideal assumptions about the primary season. The main game screen is split vertically into two areas. The top shows bar graphs for each candidate, preset to the current poll data in the selected state. The bottom shows “votes” ready to be guided into “polling doors” in the candidate’s bar graphs to “vote.”

The player clicks on the citizens in the game screen to turn them in different configurations and create a path for votes to go to the desired candidate. Gameplay is accomplished entirely with the mouse.

Creating Identification

As we both have argued elsewhere individually, video games can and should inspire player action in the real world (Frasca 2001, Bogost 2006). To encourage players to consider taking action in the real world after playing, it was crucial that the game create a link between the solitary representation of outreach and its social nature in the material world. We wanted to invite the player to identify with these virtual campaigners. The player would be much more likely to project himself or herself onto more detailed, individuated characters in the minigames. These people looked like them, their friends, their neighbors. The game’s splash screen features a cluster of these hand-drawn people for the same reason: the player’s first impression of the game would be one of sociability.

This rationale also informed the types of people we chose to include in the game. Diversity remains a social buzzword, and a game in support of a politician necessarily must admit to the variety of the American citizenry. This issue was even more critical for Howard Dean, who found support from minorities a difficult challenge. Republican and Democratic opponents alike continually criticized Dean as an elitist, a candidate who appealed only to the ultraliberal, young WASPs. For international readers unfamiliar with the term, WASP is an acronym for White Anglo-Saxon Protestants. It usually refers to the middle and upper classes especially. One memorable TV commercial run by the conservative political action committee Club for Growth, shown in Iowa in advance of the caucus, depicted an older couple showering insults on Dean’s “sushi-eating, Volvo-driving, latte-drinking” supporters (see Hallow 2004). Our decision to include characters of various ages, races, and even body types was intended to combat this overwhelmingly popular public image of the typical Dean supporter: a snobbish elitist. Despite our best intentions in this regard, the characters the player controls in each of the three minigames all appear Caucasian - a detail not lost on at least a few players, some of whom commented that the game, like the campaign, featured whites trying to get the attention of minorities.

The visual style of the characters and their environments was likewise chosen to stimulate affinity in the player. Art director Sofia Battegazzore adapted the watercolor wash appearance of the characters directly from the cartoons of the New Yorker magazine.

Cartoon-style graphics always risk the perception of childishness. The visual design thus helped set the expectation that the game was for adults. At the same time, the style evoked the broader themes of the New Yorker: society and culture.

Digital Demographics

In general, small-scale games developed for Internet delivery do not usually garner the play time of large commercial games. However, we believe that such games should not use their casual properties as an excuse to avoid detail. Even if players do not consciously note and explore such features, their presence enriches the experience by texturing it. Unfortunately, such features risk going unnoticed for posterity. While criticism is the best route for discovery and exploration of any game, we’d like to take the opportunity here to describe some of the Dean game’s subsystems that might otherwise go unnoticed.

One aspect of the process of performing grassroots outreach that especially interested us was demographics. We had no plans to give the elderly different bias than the first-time voters - the characters in the game simply didn’t have inner lives of that kind. But we did want to remind the player that people with a variety of backgrounds comprise the American population. As mentioned earlier, the Dean campaign was often perceived as a group of yuppies: “latte-swilling” youth with no understanding of middle America nor middle age. We hoped to remind the player of other voters, beyond the stereotypical leftist elites, whom the Club for Growth TV spot criticized.

The supporter tokens we used on the overview map were featureless and genderless, mostly because additional detail would be neither visible nor meaningful on that screen. Instead of creating intricate character avatars that would denote the gender, age, and background of each virtual supporter, we chose to create a label with name and age that would connote a set of potential backgrounds for the virtual supporter. Following Scott McCloud’s (1994) observations about comics and Will Wright’s about simulations (Pearce 2002), we wanted players to fill in the inner lives of these characters with their own personal experiences. We also wanted them both to recognize the supporters as credible representations of people in the material world and as strangers.

To accomplish this, Bogost created a simple procedural method to generate supporters on the main Iowa map. First, we took U.S. census data for the demographic distribution of ages and genders in Iowa, a state with a slightly larger than average population above thirty-five. Next, we acquired additional census data on the most and least popular baby names from every decade from the 1910s through the 1980s (the last decade in which people of voting age could be born as of 2003). Using the age and gender data, we built a simple generator that would balance our supporter population based on a statistical model of the Iowa population. The U.S. census even provides regional breakdowns for baby names, allowing us to configure the generator to match each supporter with a first name appropriate for his or her age and gender. We selected a combination of the most popular and least popular names, in order to avoid an army of Michaels and Sarahs. The result was remarkably effective: the game produced 28-year-old Jennifers and 75-year-old Myrtles, 52-year-old Barbaras, and 40-year-old Roberts. We hoped that players would take these simple names as an invitation to imagine the hypothetical interactions they might have with these fictional supporters.

Every time the player installs a new supporter onto the map, the game attempts to normalize the population to a statistical average for the general Iowa population. This technique contains a subtle rhetoric: the game represents the population of potential Dean supporters as analogous to the population of actual Iowa residents. Some might argue that Dean supporters would (and did) reach only those corresponding with their own demographic - young hipster latte-swillers. No matter the real demographic bias of Dean supporters, we wanted to give players a view of the superset of possible Dean supporters, to suggest that they might both look beyond the familiar and prepare themselves for conversations with them. An apparently minor feature, the virtual supporter generator was actually carefully designed to advance the game’s rhetorical position.

Despite its reasonably sophisticated computational models, the game remains a single-player affair, while grassroots outreach is inherently social. To encourage players to begin considering outlets for real-world interaction while playing the game, we designed two dynamics that relied on player-to-player contact. One of these was indirect, the other direct.⏴Marginnote gloss1⏴The idea that genres carry “ideological luggage” is perhaps most expansively explored in Fredric Jameson’s 1982 The Political Unconscious. Nick Spencer has reviewed Jameson’s more recent work in ebr’s Fictions Present thread.

— Ben Underwood (Apr 2008) ↩

Indirect social interaction was simulated through asynchronous multiplayer collaboration: time-delayed contact between individual plays of the game (see Bogost 2004). After the player completed a session, each game dynamically updated a central server with information about how many virtual supporters the current player recruited in each of the regions on the map. And each time a new player loaded a game, a software routine loaded the current levels of virtual support penetration in each region. Areas with higher support turned increasingly darker shades of blue on the map. Darker shades of blue were more receptive to additional support, and additional incremental success was easier in these areas. Both this and the regional collaboration mechanic were provided as clues in a cycling text display at the bottom of the screen.

The algorithm for receptivity to virtual supporters took these regional support levels as their primary input. A numeric indicator in the game also displayed the total number of supporters all players had recruited that day. Each night the game data reset itself, and the map appeared freshly white for its first player the next morning. A player who loaded the game late at night would benefit from the aggregate effort of all of his predecessors. Given the short-term goals of the game, we hoped that this dynamic would give new players a chance to witness a microcosm of grassroots growth every day. To reinforce the positive effects of bringing more campaigners into Iowa, the game loaded near-real time data from other game sessions played during the same calendar day. To tie the game to the real Iowa outreach effort, the game also correlated that figure with the total number of campaigners committed to travel to Iowa for the caucus.

Direct social interaction was facilitated by standard Internet communication protocols. Web-based games, especially advergames, have often included a “send to a friend” feature intended to facilitate word-of-mouth distribution of the game, and thereby the advertising message. The approach has become tired and clichéd, especially since most send-to-a-friend games offer no reason for the player to spread word of mouth save fulfilling the goals of the advertisers themselves, an assumption marred by player cynicism. To combat this trend, we wanted to offer the player in-game feedback for the extra-game contact they facilitated. Most send-to-a-friend features are one-way affairs: the player sends an e-mail message through the game and receives no additional feedback. Our version was real-time and closed-loop; we called it Recruitment.

At any time during play on the map screen, players could enter an e-mail address or instant messenger handle (AOL, Yahoo! or MSN) of a friend they wanted to contact. If the e-mail was successfully delivered or if the IM user was online and received the synchronous messages sent through the game server, the player would be rewarded with a new supporter to use in the game. Using IM avoided the nuisance and noise related to e-mail, while simultaneously communicating the urgency of Iowa outreach through the synchrony of that medium. This recruitment feature effectively gave the player a “free” virtual supporter - one that did not need to be created by completing a minigame.

Perhaps most significantly, recruitment actually correlated with the communication goals of the game itself: the intention was to simulate the effectiveness of person-to-person grassroots outreach. Recruitment via e-mail or IM took less time than playing a minigame, and thus the game’s rules privileged real-world connections over virtual ones.

To further encourage players to begin thinking about how to muster their personal networks in the material world, virtual supporters created through recruitment were displayed with the actual e-mail address or IM handle rather than a generated name. Some players even reported surreptitiously recruiting their Republican friends and colleagues in order to implicate conservatives in their support network.

Suicide Bomber to Sign Waver

When looking for a way to model the sign-waving game mechanics we ran into a problem. We had sketched a couple of options but we both agreed that having a person running with her sign along the sidewalk would work like a charm. But this design posed a major challenge: this basic mechanic was almost an exact copy of a previously released casual Web game. Our concern was not simply driven by fears of being accused of cloning this design - accusations that would be well-founded, since we were perfectly aware of this previous game. The main issue was that the game from which we were “borrowing” the gameplay in question was heavily political and controversial.

Caption: Prototype of sign-waving gameplay.

The game in question was called Kaboom! Its gameplay was simple but effective. Sadly, we can hardly say the same about its subject: your goal is to detonate a Palestinian human bomb and kill as many Israeli citizens as possible, including children. Later, Activision lawyers complained that the developers had adopted the title of the popular Atari 2600 game Kaboom, and the name was changed to the more descriptive The Suicide Bomber Game. Despite the game’s apparently crass intention, its creator has maintained the game is actually meant to expose suicide bombers as insupportable extremists. The game was condemned in the public media and both the Anti-Defamation League, and a U.S. congresswoman called for it to be taken offline.

One does not need a degree in political science to realize that politicians do not want to be associated with games about blowing yourself up in order to kill children. On a mechanical level, our sign-waving minigame had an identical mechanic: run around and click when the maximum number of bystanders surround you. But on a representational level, the games were very different: one highlights democratic speech while the other gives rise to terror. We debated for a long time but finally decided to take the risk and keep Kaboom!‘s game mechanics. We were sure that someone would make the connection eventually; Kaboom! was a well-known game. As expected, a Slashdot reader posted a comment about their likeness but apart from that, no one seemed to notice. At a semiotic level, the games were totally different; only an experienced gamer would be able to identify the similar mechanics at their core. But as more and more people become literate in games, we can easily imagine a future where this kind of intertextual commentary will raise more eyebrows.

It would take a longer article to argue if it is ethical to copy game mechanics. In this particular case, we both acknowledge that our game is based on Kaboom! but we also feel that there are enough differences on other, non-gameplay levels, to set them apart. In any case, the fact that the first official U.S. video game used for a democratic campaign owed something to an extremely violent game is, in our opinion, an example of how totally different ideas can coexist and influence each other during these early, experimental days of political gaming. More than anything, we wanted to “redeem” the core game mechanic, to show that it need not be associated with violence.

Endorsed Game-Based Political Speech

Game typologies, like any form of genre classification, are always tricky. It is hard to find clear-cut categories where one can fit different games. The “political” game category can be applied to agitprop Web games, but also to commercial games dealing with armed conflict, economics, or urbanism. Since all cultural products do carry ideological luggage, we could argue that all games are indeed political. For this statement to be true, the term “political” should be taken in its broadest possible sense, understood not simply as partisan politics but rather as all strategies and ideas that permit social coexistence. In this tradition, games - and not just electronic games - have a long political history. The dichotomy between good and bad guys is evident from children’s games involving rocks, arrows, swords, pistols, or laser guns and from actual military simulations, both paper- and computer-based.

Different categories have emerged in order to classify these “political” games. Propaganda games like Under Siege or America’s Army seek to recruit new members and spread their ideology. We have also used the term “campaign” games to refer to video games such as The Howard Dean for Iowa Game, Tax Invaders, Activism, or Cambiemos.

It is definitively beyond the scope of this article to create a history of political games, but we feel that we should still mention some examples. A recent exhibit at Cornell University featured the Cleveland Re-election Game, circa 1893, built around U.S. President Grover Cleveland’s second term. However, it is unclear if this game was officially endorsed by the candidate. Nineteenth-century British suffragettes also created thematic games like Panko or Suffragettes in and out of Prison - and financed their campaigns through their sale. Panko was a card game like rummy, and Suffragettes was a board game similar to Chutes and Ladders (see Rover 1967). Probably the most relevant example of early political video games is Chris Crawford’s Balance of Power.

The authors behind these examples had a clear intention of conveying their ideas through games but, of course, even if there are no intentions the game can be definitively qualified as political. As many critics have pointed out, SimCity is a clear case of a game that takes a position on several political issues such as taxes, public transportation, and ecology. In other words, the game designer does not necessary need to be an activist for a game to have a political register. Certainly, author intentions are always difficult to establish, and the postmodern school even argues that they should be completely ignored. In any case, during these early days of political video games, it is useful to take the author’s intentions into account because they can help us to understand the mechanics behind game persuasion. This explains why the motto behind our joint Web site, Water Cooler Games, is “video games with an agenda.” However, we believe strongly that every game carries some ideological baggage, independently of their open, hidden, or unconscious agendas.

Games with clear agendas make better examples to be analyzed, especially because the idea of games as ideological artifacts can be quite surprising to many people. In fact, when Frasca defended his thesis on political video games (Frasca 2001), the first question he was asked by his committee at Georgia Tech was “Do you seriously believe that games can change the world?” This was not simply mere academic skepticism: in spite of a long tradition of marrying pop culture and politics, video games were - and still are - perceived as too trivial, too childish to deal with the seriousness of campaigns and policy making. No matter how optimistic we could have been by then, we would have never even considered the possibility of campaign videogames just a few years ahead.

Still, and in spite of having both participated in several games for different campaigns, we do not kid ourselves: campaign games are a rarity so far. Videogames may be experiencing an explosion within our culture but they still need to mature as a persuasive medium. Yet just ten years ago, it was almost unimaginable that a politician would have a Web site. It would now be crazy to think of a politician without one - or without a blog and a mailing list. Believe it or not, television was once thought to be too trivial for political campaigns and its role did not become pervasive until the broadcast of televised debates in the 1960s.

Even though the 2004 U.S. election gave birth to video games as a new form of political expression, a much older genre found itself in the spotlight: documentary film. Certainly, the election would not have been the same without Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11 (Moore 2004). It was the first time that the outcome of an election was influenced by a documentary film. After the election, it was common to hear that Moore’s film could not have changed the outcome. We strongly disagree. If Moore had not launched his film, Bush would probably have won by a much larger percentage. More important, the film created an undeniable discourse around American foreign policy, a very real outcome indeed. Maybe some day a video game will play an equivalent important role. As a genre, it took documentary film almost a century of evolution to acquire such political relevance, and this is why we should not expect political games to play a protagonist role any time soon.

It is particularly problematic to be both designers and researchers, because our agendas conflict all the time. As academics, we would have liked to disclose as much information as possible during the campaign. As hired guns, we had to respond to our client’s strategies and keep quiet about details (such as the role of the game in the broader pre-caucus communications plan) because they were the ones running the big picture and we were merely providers of a service. The same applies when dealing with other political games. When the Republican Party “answered” the Dean Game with Tax Invaders, as partisans we felt like making fun of it (it is technically so poor that we joked that it was coded by Bush himself). While the GOP has long since taken the game off their official Web site, as of summer 2005, it was archived on the popular independent Republican site KerrySucks.com. On the other hand, as academics and professionals, we should respect our colleagues’ work and their relevance in the broader cultural landscape. These conflicts of interest are particularly evident in our weblog postings and press interviews; for example, in a discussion of Tax Invaders on Water Cooler Games, Ian Bogost offered, “As another public example of political games, I’m happy to see the Bush camp trying things like John Kerry Tax Invaders. But does the GOP really think that what President Bush needs is a representation of his head firing bullets?” There is no magical solution to this conflict of interest. We draw attention to it not as an excuse, but as an example of how torn we felt during the development of this and other campaign games.

Campaign strategists use their media products as ammunition. Usually, the pace of the campaign is so fast that television commercials may be taped in the morning, edited in the afternoon, and aired at night. At other times, communications get canned for a few days and even weeks until the campaigners decide to release them. The fact is that after we completed the production of the Dean game, it took over a week for the campaign to announce it properly. After crunching for four weeks, it was disappointing to see how much time it took the campaign to release and promote the fruit of our labors. We suspect that the delay was not strategic but influenced by other campaign events - the campaign was too busy to pay too much attention to a video game that, after all, was an experiment. In a certain way, the delay was actually helpful, because it allowed us to plan our own communication strategy.

As designers, we were interested in generating attention for our work in persuasive gaming. And as academics, we also saw an incredible opportunity to draw significant attention to the nascent field of political games. We even negotiated with the Dean campaign about how much freedom we would have to advertise our production and on which terms. This was not particularly hard, since nobody really knew if the idea of official campaign games made any sense, and because we were producing this project well below its fair cost.

Once the Dean campaign greenlit the game’s launch, we were given a few hours before the press release went public to announce the game to a select group of bloggers. This was coherent with the campaign’s ideals of experimenting with the net and its grassroots effects. However, the players drawn through the blogs were very few and the server statistics only spiked after the game was featured in traditional media outlets such as the New York Times or Good Morning America. Server stats only refer to the number of players; they cannot qualify other characteristics. Even if the number of players referred by blogs was not overwhelming, this strategy certainly reinforced the idea that this particular campaign was paying special attention to alternative communication strategies.

Online games offer the possibility of getting access to a lot of feedback from players. A few months before the launch of the Dean game, Frasca and his team had launched their game September 12th, a critique of Western foreign policy in the Middle East. In the game, players could, if they wished, fire time-delayed missiles into a Middle Eastern town to attempt to kill terrorists. However, the missiles inevitably destroyed buildings and killed innocents as well as terrorists. Those characters nearby would mourn over the dead innocents and some of them would in turn become terrorists. The game had caused its share of controversy by then, and it was played by several hundred thousand players. We used this experience about how players reacted to a persuasive video game in order to prepare for possible negative feedback.

Even though September 12th and the Dean game are quite different in theme, we were right that they would trigger some similar reactions. It was not uncommon for both players and critics to argue that the game was not fun or not fun enough. This is the kiss of death in any critical discussion because it lowers the bar to a matter of taste. There is a long tradition of art criticism, and this is why we rarely see a critic dismiss a painting because “it is not pretty.” Sadly, game criticism is still maturing and sometimes we cannot get beyond the “Like it”/“Don’t like it” dichotomy. Clearly, a persuasive game cannot be judged like a console game - and this divergence goes beyond mere production quality. Unlike commercial games, the ultimate goal of a persuasive game is not to provide fun but to convey a message. Certainly, the experience must be compelling for the player. But replayability, often held up as a litmus test for commercial games, is not essential in this new field.

The whole concept of replayability has economic undertones: you are getting a game that will provide pleasure for a certain amount of time for a certain amount of money. When we created the Dean game, we assumed that most players would not spend more than ten minutes at a time with it. Actually, the average playing time was longer than that and we were the first to be surprised when the server stats showed us that some hardcore Dean supporters had been playing for hours, and returning day after day to contribute more virtual support.

Another popular criticism is that the game modeled the campaign but failed to convey Dean’s own ideas. This is a clear example of how hard it is to criticize persuasive communication - and it applies not only to games but also to any form of advertising. The fact is that we did not model Dean’s ideas because the campaign expressly wanted us to focus on the grassroots campaign itself. This is also probably why Dean failed as a candidate. He orchestrated a brilliant campaign that revolutionized the way U.S. campaigns are done, but he failed to focus on convincing voters that they should vote for him. Bogost took this lesson to heart and later in the campaign focused on public policy issues over political practice in Activism and Take Back Illinois.

In Activism, the player managed six public policy minigames, which he had to play simultaneously. The player could alter the relative importance of each policy issue, and the gameplay forced the player to pay more attention to the policy issues he declared the least interest in. Take Back Illinois simulated a party position on four public policy issues in greater detail - medical malpractice reform, economic development, educational reform, and voter participation. To win each game, the player had to embody the party position on each topic in order to learn that position and subsequently to consider, support, or oppose it. Unlike the Dean game, both Activism and Take Back Illinois addressed public policy issues, rather than campaign communication.

But one question came up in every media interview we did about campaign video games: can a game change the outcome of an election? By this standard, the game was a huge failure because it did not prevent Dean’s catastrophic collapse. The logic behind this question resembles the thinking behind similar cursory arguments as to the role of games in education or whether they lead to violent behavior. Our world is too complex to be simplified into a series of causes and effects; the political environment is no exception. A campaign video game is merely one message within an ecology of other messages. Certainly, some communications have a stronger effect than others - a tape showing a politician performing some act of corruption could end his career. However, most propaganda simply reinforces certain ideas and seeks to appeal to a specific audience. Similarly, a political game can better speak to a specific group of voters. Games may invoke contemplation or reinforce ideas, but they can hardly decide the fate of an election.

Meta-Messages and Balloons as Political Speech

While it is worthwhile to explore the possibilities of modeling political ideas through gameplay, it is also important that a campaign game communicate more than its political payload. Campaign games also work at a higher level, conveying more ideas that are not necessarily connected to their design.

One of the most important meta-messages that campaign games convey is the fact that the candidate is pioneering a new political form. This makes the game instantly newsworthy. No matter if the game is fun or boring, pretty or ugly, interesting or not, the association between video games and politics attracts the attention of the media. During a political campaign, the budget for media advertising is always scarce (unless the candidate is a media mogul), and therefore any news coverage is highly valued by the campaign strategists because it is perceived as free advertising. If the Dean campaign had invested the game’s budget into TV advertising, they would not even have been able to buy a few seconds on-air. However, because the game was instantly snatched up by journalists, it received televised and printed coverage for the Dean campaign whose value well exceeded the game’s development budget.

Another meta-message is that the candidate sets himself apart by using alternative communication techniques. This is a double-edged sword. The campaign’s intention was to use video games as a complement to their broader online strategy. Ideally, by releasing a video game, Dean would have been perceived as an innovator willing to address a younger audience through the media codes and conventions with which they are familiar. The risk, of course, was that he could have been accused of trivializing campaigns by using an unserious genre such as video games, or deploying the medium to seduce the interest of young people. As designers, we were particularly concerned about this problem, even though there was actually no negative impact. In retrospect, we may have wrongly expected that the game would have a major impact on the campaign. In other words, if the game had been perceived as a threat, we are convinced that it would have been attacked. The Dean campaign crumbled after he lost the Iowa caucus and the game was effectively retired, noted for its innovation but implicated in the campaign’s overall failure.

We must keep in mind that the influence of these meta-messages may only persist during these early stages of campaign games. As we grow accustomed to the concept, the medium itself will seem ordinary and cease to be newsworthy. Only time will tell if video games will not be judged for trivializing the “seriousness” of political games. Of course, recent public bias against video games has arisen at the hand of politicians themselves. Senators Joseph Lieberman and Hillary Clinton demonize video games for their own agendas, effectively dismissing video games as a form of political communication. In any case, on further reflection, political campaigns are also driven by triviality. Just think of the importance of balloons in party conventions. If balloons, funny hats, badges, singing, and dancing are all accepted elements of political speech, we are certain that there must be some room left for video games.

Archive Early and Often

We hope this chapter provides a behind-the-scenes perspective on the creation of the Dean game and useful reflections upon the nature of campaign video games in general. Even though games and video games have been used historically as a satirical approach to politics, it was a design challenge to create a video game that was officially endorsed by a candidate.

Are video games going to become as pervasive as other campaign tools? Our answer as professional developers of game-based political marketing is a resounding “yes.” As academics, we are still convinced that the genre has a great potential. But we should caution that we are witnessing the birth of a genre, and it is likely that it will take many years for it to become widely accepted. This situation presents an opportunity for early adopters because these first campaign games are gathering exceptional attention from the media, and this attention will likely fade out as the genre becomes more established.

So far, all we can say is that the game certainly triggered a trend. On a personal level, we have both created other games after the Dean campaign, for both the same U.S. election (Activism, Take Back Illinois) and for other presidential elections (Cambiemos). In addition, we have tracked some 200 political games of various forms on Water Cooler Games. And there are surely more that we have not yet seen.

But many of these games are ephemeral and risk being lost to history. We have realized the hard way that most campaign games disappear quickly once the elections are over. Campaign committees dissolve and it is almost impossible to contact developers of such games. These challenges are probably normal for scholars researching traditional campaigns, given the fact that during election time there is an abundance of information and after it is over, it suddenly vanishes. But the purely digital nature of these games exacerbates their transience. Our advice for colleagues interested in political video game research is to gather as much information as possible as soon as the games are out. Archive early and often.

Can campaign games become a useful tool for fostering debate and critical thinking during election time? Or will they simply erode political speech while replacing it with mere entertainment? If we take a look at media history, there is no clear answer for these questions. We do know that communication genres can be used both to manipulate and to encourage free thinking. As researchers, we remain carefully skeptical. But as developers and activists, naïveté is an essential requirement - only idealism can provide us with the thrill of exploring new techniques for reaching more people with new ideas. Changing politics, changing the world - it is all within reach, as long as we remain playful and we have a little fun while doing it.

References: Literature

Bogost, Ian (2004). “Asynchronous Multiplay: Futures for Casual Multiplayer Experience.” In Proceedings of the Other Players Conference, edited by Jonas Heide Smith and Miguel Sicart. Copenhagen: IT University of Copenhagen.

Bogost, Ian (2006). Unit Operations: An Approach to Video gameVideo Game Criticism. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Frasca, Gonzalo (2001). “Video Games of the Oppressed.” Master’s Thesis, The Georgia Institute of Technology. Excerpted in (2004) First Person: New Media as Story, Performance, and Game, edited by Noah Wardrip-Fruin and Pat Harrigan. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hallow, Ralph Z. (2004). “Conservatives launch TV attack ad on Dean.” Washington Times, January 6, 2004.

Johnson, Stephen (2003). “SimCandidate: Video games Simulate Sports, Business, and War. Why Not Politics?” Slate, December 16, 2003.

McCloud, Scott (1994). Understanding Comics. New York: Harper.

Moore, Michael (2004). Fahrenheit 9/11. The Fellowship Adventure Group/Wild Bunch.

Pearce, Celia (2002). “Sims, BattleBots, Cellular Automata, God and Go: A Conversation with Will Wright.” Game Studies 2, no. 1 (2002).

Perec, Georges (1969). La Disparition. Paris: Gallimard.

Rover, Constance (1967). Women’s Suffrage and Party Politics in Britain, 1866-1914. Toronto: Toronto University Press.

References: Games

Activism. Ian Bogost; Persuasive Games. 2004a.

America’s Army. U.S. Army. 2002.

Balance of Power. Chris Crawford; Mindscape. 1985.

Cambiemos. Gonzalo Frasca; Powerful Robot Games. 2004. .

The Howard Dean for Iowa Game. Ian Bogost and Gonzalo Frasca; Persuasive Games. 2003.

Kaboom. Larry Kaplan and David Crane; Activision. 1981.

Kaboom! (aka The Suicide Bomber Game). Anonymous (Fabulous999); Newgrounds. 2002.

September 12th. Gonzalo Frasca; Newsgaming.com. 2003.

SimCity. Will Wright; Maxis. 1989.

Take Back Illinois. Ian Bogost; Persuasive Games. 2004b.

Tax Invaders. Republican National Committee; gop.com. 2004.

Under Siege. Afkar Media. 2004.

WarioWare, Inc.: Mega MicroGame$. Nintendo. 2003.

WarioWare, Inc.: Mega Party Game$. Nintendo. 2003.

WarioWare Touched!. Nintendo. 2003.

WarioWare Twisted!. Nintendo. 2004.

Cite this essay

Bogost, Ian. "Video Games Go to Washington: The Story Behind The Howard Dean for Iowa Game" Electronic Book Review, 9 April 2008, https://electronicbookreview.com/publications/video-games-go-to-washington-the-story-behind-the-howard-dean-for-iowa-game/