William Gaddis’s Unpublished Screenplays, Stage-Drama Scripts, Prospectuses for Film & TV, and Poetry: An Archival Guide

A survey of Gaddis’s known and archived unpublished creative work in poetry and drama, from a parodic Elizabethan play and the complete script of Once at Antietam to a full western film screenplay and a year of failed pitches for TV drama. Each entry contains archival location information, historical information, description and analysis of the archived work, and discussion of any connection to the eventually published fiction.

Various materials from the Gaddis Archive by William Gaddis, Copyright © 2024 The Estate of William Gaddis, used by permission of the Wylie Literary Agency (UK) Limited. Due to the copyrighted archival material reproduced here, this article is published under a stricter version of open access than the usual Electronic Book Review article: a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 license. All reproductions of material published here must be cited; no part of the article or its quoted material may be reproduced for commercial purposes; and the materials may not be repurposed and recombined with other material except in direct academic citation – https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ .

William Gaddis thought of himself as a prose writer, and all that comes down to us in published form are his novels, some very occasional non-literary essays, and the works in various genres that he published, sometimes anonymously, at the Harvard Lampoon more than a decade before his debut novel was published. Yet his archive preserves a variety of works in poetry, stage drama, screenplay, and prospectus for short TV drama.1

Some of this has long been known about and was acknowledged or publicly promoted by Gaddis himself – most notably the play Once at Antietam (worked on from 1959-62) which resurfaced reproduced in parts throughout A Frolic of His Own as Oscar’s stolen work, and which Gaddis made no secret of having originally written himself with many of the same ambitions that Oscar has for it. On the other hand, the spate of proposals for television work that Gaddis put together throughout early 19552—after the publication of The Recognitions failed to generate an income that could support his young family—was a part of his career that he retrospectively acknowledged even less than his time as a corporate writer. A Faust-Western screenplay initially drafted during the time of least progress on J R went similarly unacknowledged in public, even though Gaddis kept trying to get it produced over the course of a decade and initially (and more publicly) planned a prose-ification of it to be his next novel after J R (see entry on Dirty Tricks, below).

Gaddis makes sporadic reference to his thoughts on non-prose media in his letters, his corporate work, and other sources. While he never addresses the question of medium in extensive detail, nonetheless his work across other forms no doubt informed his use of prose in his successfully published work, and gave him the ability to pronounce (when other people raised them) upon topics like “the adaptation of ‘serious’ fiction for television” (Letters 354). In that 1980 letter, which Steven Moore identifies as a response to a student enquiry, Gaddis stresses that he thinks J Rwould be well-suited for television because its lack of interior psycho-narration would mean no need for the awkwardness of “extended voice-over,” while for The Recognitions he preferred “the larger format of a full length motion picture.” He clarifies, though, that versions of the same fiction in different media would not, for him, be versions of the same work: “An incisive & highly amusing television presentation could, for example, be drawn from Samuel Butler’s Erewhon, but it would not be Butler & it would not be Erewhon.” This was the judgment of a man who had recently tried to adapt his own novel J R for the stage (see entry on The Secret History of the Player Piano, below) and energetically pursued someone else to make a film version for him: it did not concern him that this would not have been J R, and would not have been Gaddis. The various texts I address below raise the related question of how any of Gaddis’s non-prose works, none of which he managed to publish or get produced beyond the Harvard Lampoon, relate to “Gaddis” if we understand “Gaddis” as the author-figure associated with his five published novels.

At any rate, the archive reveals that William Gaddis often tried to make “William Gaddis” the name of more than a novelist. Researchers and scholars have written little on these documents and have remained unaware of their existence. In the present guide, I introduce these documents to the reading public, in many cases for the first time, with archival box/folder location information, date, brief descriptions and analyses, and indications of any clear relation to Gaddis’s published work or references to the material in published criticism or Gaddis’s published letters. Where possible, I include information on how his pitches to film-makers, theatres, and TV networks were received.

A separate document (co-authored with Joel Minor) in this same special journal issue offers a comparable guide to Gaddis’s unpublished prose fiction, from short-stories to prototypes of his novels: (Chetwynd & Minor, “William Gaddis’s Unpublished Stories and Novel-Prototypes: An Archival Guide” - henceforth “Chetwynd&Minor, Fiction Guide”).

*

A few clarifications about contents and method before the guide begins.

As with any project surveying an archive as large and loosely filed as Gaddis’s, I can’t claim to be totally comprehensive here because there is a good chance that relevant documents are still resting in their folders waiting to be found. While the TV proposals I discuss here all seem to date to late 1954 or early 1955, a draft letter from December 1955 in Box 21, Folder 5 mentions having sent a scene breakdown for a 1-hour TV play to NBC in August of that year, and asks for follow-up. I have not been able to find any other record of that TV proposal, but it may be preserved somewhere. Some of the single-page poems discussed here are not indexed or mentioned anywhere else in Gaddis’s archive, and were discovered only by chance in folders that make no other reference to poetry. No doubt other comparable documents await discovery, at which time the current document will need supplementing.

I do not, meanwhile, attempt to address any of Gaddis’s Harvard Lampoon work (excepting “The Laughing Boy – Blues” which he filed, for unclear reasons, with his other unpublished poetry – see entry below): Lampoon contributions were published, at Gaddis’s behest, and remain accessible wherever the Lampoon is archived. Steven Moore has usefully identified which of the Lampoon pieces from volumes 127 and 128 (1944) were written by Gaddis, even under a pseudonym, and Moore’s personal archive at Washington University in St Louis’s Olin Special Collections Library contains copies of all this work.3 However, the methods he used to identify the pseudonymous authors in those editions were not possible with two other issues Gaddis was involved with (volumes 126 and 129) and so it remains unclear which pseudonymous contributions he wrote for those issues.4 In the absence of definitive information about what constitutes Gaddis’s full Lampoon oeuvre, and counting Lampoon publication as publication, I hold off from addressing any of it here.

I omit further citation for individual documents where the “Location in Archive” part of the relevant entry already contains sufficient Box/Folder information. I give page references only where the draft itself has page numbers. References to other relevant archival material are separately cited or endnoted. References to published interviews, studies, and so on are by author-name or parenthetical, and refer to a works-cited at the end of this document.

There’s a lot of material here and readers might not want to grind through it from start to finish. I suggest the following cross-genre Top Five as places to begin, for their combination of relevance to Gaddis’s published work and interest as independent (completed or proposed) artworks:

Faire Exchange No Robbery; Dirty Tricks; Unfortunately; Untitled Adaptation of Simone de Beauvoir’s The Mandarins; “MAJORITY.”

Readers and researchers interested in seeing any of these documents should contact Special Collections at the Olin library of Washington University in St Louis to arrange visiting times and item access requests.

I hope this guide will encourage more investigation of these materials and their implications for the understanding of Gaddis’s work.

I address first the screenplays and drama, then the TV-fiction proposals, then the poetry.

William Gaddis’s Unpublished Screenplays and Stage-Drama Scripts (Chronological)

Title: Cartes Sur Table

Location in archive (Box.Folder): 86.3 (“Drama: Cartes Sur Table”)

Date: 25 July 1943

Complete? Yes

Extent of preserved material: 4-page typescript, hand-dated.

Description: Sub-headed “A harlequinade for our time in one scene,” this seems to be Gaddis’s most explicit topical engagement in fiction or prose with the ongoing second world war (see also “REASONS” and “MAJORITY” among the poems, below). The preserved copy seems to be final, with no further annotations beyond the date, though some stage directions are blacked out.

Against a painted backdrop of a city on one side and war scenes on the other, the set comprises a table with a glove, a wine glass, and a book on it. Three characters surround it: Columbine, Harlequin, and Pierrot, wearing masks, with Harlequin further costumed to imply a bon vivant, Pierrot an artist. They are returning to each other’s company after long parting, and stress their “need” for each other’s lovely company: “you do nothing, you think of nothing, but you are exquisite.” Pierrot promises to teach Columbine to read, but she demurs at such distraction from exquisiteness: “Must one know this to enjoy wine, to own the stars and be one of them?”

As the conversation progresses, though, both Pierrot and Harlequin become distracted by something they can’t see. Harlequin muses “Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori – yes, that’s the line […] he tears off his mask, revealing a stronger face, excited, inspired.” And having removed his mask, he vanishes. Pierrot and Columbine are briefly confused, but Pierrot himself looks to the back of the stage and intones “thousands waiting for a hand to help them, to help the climb, build… (he removes mask slowly, revealing a young inspired face).” And with this inspiration he too vanishes, leaving Columbine alone on stage. Initially dismissive—“Well, this is all very silly”—she turns to bitterness: “(she reaches up, slipping off her mask) le dessous des cartes… (the face we see is hard, almost cynical. Her limbs no longer seem lithe.”) Finally, though, she chooses to restore the mask, telling the audience “We are the only things that last […] it is the outside that matters.”

Analysis: This harlequinade seems to be an aesthete’s argument against commitment, lamenting that in “inspired” mouthing of the slogans of war and subordinating their exquisite artifice to a collective project, what is beautiful in young men gets destroyed, leaving their women to keep the aesthetic flame burning, however abandoned and unable to recover lost innocence. Columbine’s contrastive pun on different “outside”s organizes the play’s conflict of values: the Wildean commitment to the sufficiency of a world of beautiful exterior surface, against the worldview compelled to find something practical or political to subordinate itself to “outside” mere beauty and friendship. The play opts for one of these over the other, even though “our time” has chosen the other way. That will not “last,” as the unmasked men vanish mortally, while the paradigmatic characters of their masks can persist. This unilateral aestheticism is rare even in Gaddis’s early writings, and “Cartes sur Table” is thus noteworthy as an extreme in his early oscillations between worldviews.

The French idioms here also bear some significance: Pierrot vanishes after murmuring “Tous songes sont desonges” (“all dreams are lies”), which quotes the legendary renaissance soldier Blaise de Montluc. On the one hand it’s an expression of materialist cynicism, the kind that might pressure an artist like Pierrot from his vocation into the world of politics and war, while on the other it critiques the elevation of war itself into an aspiration: like Harlequin’s “Dulce et Decorum Est”—which nods to a heritage of poetic disenchantment via Wilfred Owen and others—the anti-aesthetic fetishization of war-as-serious-reality may itself be just another deceitful phantom. Columbine’s lament to herself about “le dessous des cartes,” meanwhile, ramifies through a variety of meanings. In her context, it seems to translate idiomatically to “the subordinating of the world to maps”: that is, giving reductive external shape and direction to something that should have its own level of existence. It echoes the play’s French title: “cartes sur table” in this light (with “carte” as map) would mean “putting maps on the table,” or bringing maps to bear on the world. In its more idiomatic meaning outside the echo of Columbine’s words, though, it means simply “Cards on the Table,” which can indicate either the final moment of an endgame being resolved, or (in its idiomatic English sense) the revelation of a previously implicit attitude. This might refer to Gaddis himself staking out a very definite position in the dilemmas that pull Pierrot and Harlequin away from Columbine.

As well as its aestheticism, “Cartes Sur Table” also employs some clunkily proto-postmodern (or cod-Pirandello) stage metafiction,5 along lines he returns to in 1947’s (posthumously published) prose theatre tale “The Rehearsal” (see entry in Chetwynd&Minor, Fiction Guide).6 Pierrot, speculating on what happened to make Harlequin vanish, ruminates “Do you know, Columbine, sometimes I think there is a force that controls us, that writes every line that we speak.” Blacked out stage directions (legible through the faded blackout) announce: “(DUE TO LACK OF SPACE, WE ARE FORCED TO REMOVE THE CHARACTER HARLEQUIN).” What “lack of space” might mean in the context of war and commitment, or what analogy might exist between the “force” of the creating playwright and the forces that draw the men away from Columbine’s exquisitely hermetic world, is not really pursued. But scholars interested in Gaddis as a metafictionist of technical artifice will find “Cartes Sur Table” salient.

Relation to Gaddis’s Published Writings: The relationships between art and commitment, authenticity and surface, are important to The Recognitions. That novel’s Town Carpenter gives a lecture on the unfulfillable promise war makes to “committed” young men:

With no idea of a hero, you see, but they need them so badly that they make up special games […] they arrange whole wars which have no more reason for existing than the people who fight in them, and a boy may become a hero fighting for a life that’s worth something for the first time, threatened with loss of it, that or dying to save the lives of people who’ve no idea what to do with them (408).

J R implies that the writer-character Schramm’s World War Two experiences were a large part of his suffering and eventual suicide even as they played an important part in his creativity, and “Cartes Sur Table” offers an extreme early scepticism about war’s relation to good art, and war art’s compatibility with worthwhile living.

Other Notes and Mentions Elsewhere? Given the play’s concern with what is real and what is delusion, you may hear in Columbine’s resigned “dessous des cartes” a nod to France’s primary philosopher of knowledge-rooted-in-self-knowledge: what it means to be Under Descartes in early Gaddis is something that philosophically inclined scholars might pursue.

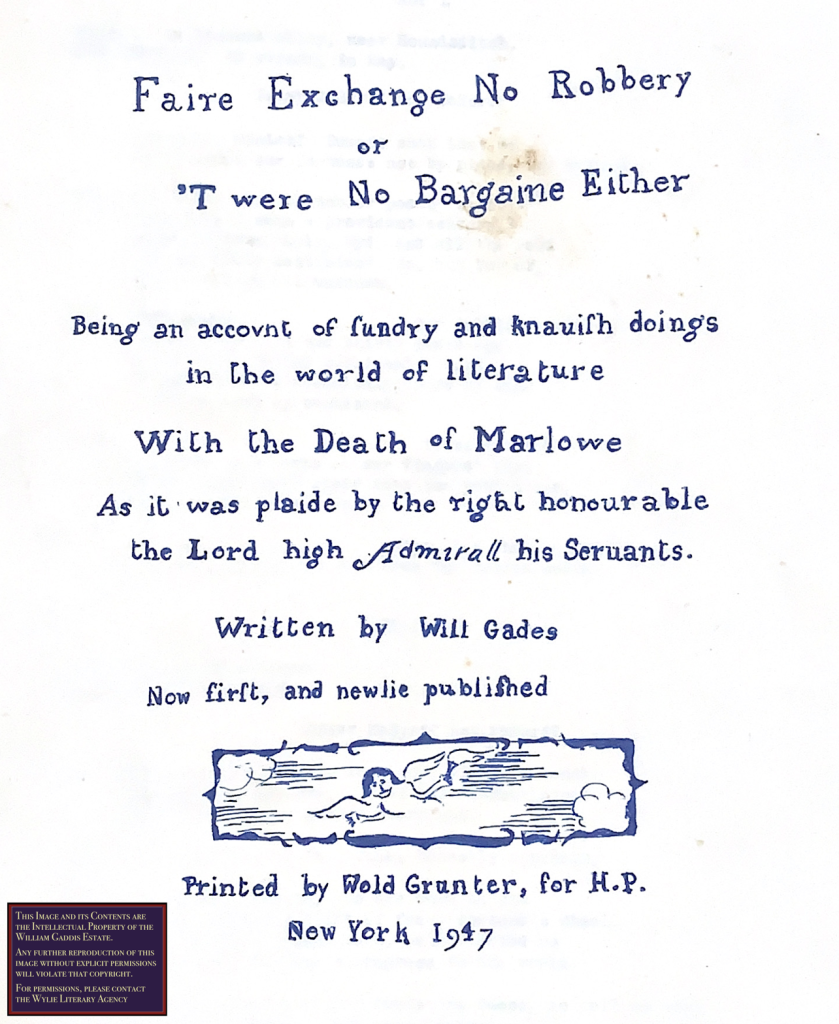

Title(s): Faire Exchange No Robbery, or ‘Twere No Bargaine Either

Location in archive (Box.Folder): 86.5 (“Drama: Faire Exchange No Robbery”)

Date: Dated 1947 (and located to New York, where Gaddis lived that year) on handwritten title page.

Complete? Yes

Extent of preserved material: Three typescript copies, one cut in half down the middle.

Description: A ten-page, five-“Act” drama (each “Act” is a single short scene) in cod-Elizabethan iambic pentameter, with an ornately calligraphic and colophon-deviced hand-written/drawn title page (See Figure 1). This gives information about playwright (“Will Gades”), performers, contents (“With the death of Marlowe”), and publisher (“Wold Grunter,” Gaddis’s old dog: see Jeffrey Severs’s article on the play in the present special journal issue).

The play itself concerns the efforts of two anthologists—McSerff and McNorff—to secure the rights to the poems of their era’s leading poets and dramatists, from current celebrity Christopher Marlowe up to and including the then two-year-old Robert Herrick (who speaks his lines like an adult).

Act I sees the anthologists scheming to get rich by monopolizing the poetry audience and hence cornering the marker in poets’ reputations: (“So, but for us, // They might all go unknown”).

In Act II they seek out Marlowe at The Mermaid pub. They having introduced themselves as Anthologists, he calls over Ben Jonson whose vaunted knowledge of Greek helps identify them as “pickers of flowers.” Marlowe’s misgivings (“A gruesome word, in sooth, // And sounds presumption in its veriest tones”) dissuade Jonson from signing with them, but not Shakespeare who the anthologists note “would be popular, and that’s enough.” Marlowe, though, chases them away with threat of violence.

In Act III, word of this new “foreign race and creed” in “the literary world” has spread to other poets, and Walter Raleigh plans to sail to Anthologia to plunder it for his queen. The anthologists themselves arrive and a discussion ensues with the poets about the merits and risks of the proposed project: it may set you “next macaronic verse // of duller lights,” but would ensure “The heightening of popularity” and offer “An honor to accompany one another.” Shakespeare again is persuaded—“The mass I write for—dear dark human pie. // Where do I sign?” but Marlowe arrives late to issue dire warning against “signing down your names, and losing there // Th’identity you’ve worked so to declare.” He spikes the just-signed contracts on his sword and plunges them into a fire. The anthologists resolve apart to kill him.

Act IV performs the death of Marlowe, the anthologists having disguised themselves as common drunks in order to kill him in what looks like a spontaneous brawl. In stabbing him, they declare “Not that I loved thee less, kind cunning poet, // But even art must feel the tinker’s awl”: in other words, the creative poet in language must always be beholden to the physical process (and business) of book-making (and selling). Though shortest by word-count, this would have been the longest scene in hypothetical performance due to Marlowe’s stage direction “He drinks steadily for two hours.”

Finally, in Act V, the anthologists return upon the poets lamenting Marlowe’s death and bend the conversation to getting the anthology back up and running. They briefly look like succeeding before a change of heart among the poets. The anthologists are cast out—“nor ever show thy noses // where honesty finds trust, and truth reposes,” but not before they can give their ominous sign-off: “Your pricks of conscience will avail naught // against the onslaught that our race will make // upon the broken back of lit’rature.” They foretell a day when the names of almost every poet on stage (baby Herrick excepted) will be better associated with commercial products or slang. Anthologists banished, the poets note that it isn’t a proper play until a woman turns up, and with a blare of trumpets the woman they have all been hoping for appears. On her benediction the play ends.

Analysis: However simple and condensed, Faire Exchange does manage to sketch out a coherent worldview of commerce, contract, art, posterity. In this world, there are truly independent artists like Marlowe; there are sponges like Shakespeare who achieve what they achieve by a shameless openness to influence, source, and opportunity; there are artists who passively take cues from such charismatic figures; and then there are the covetous interlopers into the “world of literature” (a repeated phrase) whose ability to siphon off the material rewards of writerly labour depends on their ability to sell their parasitism as aid.

Gaddis’s writing here, though, is often more skilful than the parodic premise might suggest. For one thing, it shows that he has some grasp of the affordances of iambic pentameter whether coupleted or blank (see, for example, the mid-line rhyme above that contrasts the “naught” of poetic refusal with the “onslaught” of the anthologists, or the Ee Ar Ee Aw sound-patterns of “even art must feel the tinker’s awl,” which preserves the way much Elizabethan pentameter incorporates the 4-beat alliterative heritage it succeeded). Another of its merits is an occasional semantic density that also lives up to its Elizabethan models (and to Gaddis’s mature writing). The foregrounding of “anthologist”’s root in flower-plucking, to take a simple example, conveys that the flowers that are getting plucked will die torn from their roots, without the play having to spell this out explicitly. The anthologists’ killing line “Not that I loved thee less, kind cunning poet, // But even art must feel the tinker’s awl,” meanwhile, sums up the whole play with real precision: the anthologist calling the poet “kind” replicates the false claim to kinship and shared enterprise that Marlowe has already resisted, while “cunning” emphasises the contrast between perceptive intelligence (Marlowe’s) and the word’s origin in sharpness of blade (the stabbing anthologist). The tinker’s awl, meanwhile, is the tool by which holes were made in paper such that pages could be bound together in a book. Here Marlowe the artist is himself being pierced by such an awl, which emphasises that however airy and free of the material world literary “art” may be in its initial conception (Marlowe conceives his career as happening within the “world of thought” (Act III)), it always relies on physical embodiment if it wishes to reach a wide audience whose response makes it art (consider Gaddis’s many later pronouncements about the need for readers to play their part in making a work happen). And by this same metaphor, Marlowe himself (or at least his “art”) is one of these pages that the anthologists need to pierce with their awl (ie kill) if they want to usurp the right to anthologise his work. “What’s any artist but the dregs of his work?” (Recognitions 96) is one of the most widely cited summaries of Gaddis’s attitude to the relationship between the actual author and the finished artwork, but as this play suggests, the dregs of the physically embodied artist are an avenue of vulnerability for the art itself. The anthologist’s complex and astute metaphor, meanwhile, identifies his sword with the craftsman’s awl, and hence re-establishes the division (the lack of “kind” relation) between the “poet” who deals in “art” and the anthologist whose work is more comparable to that of a physical craftsman. This dense awl image further hints at the anthologists’ dependent lack of individual creativity since the very act they avenge by awl-stabbing Marlowe is his own awl-like piercing of their signed contracts.

Not all of the play is written with this level of fullness and precision (too much of one short act is taken up with an unilluminating anachronistic riff on drinking cocktails which is presumably meant to establish some kind of analogy between cocktail and anthology),7 but few of his other 1940s writings contain so many of the coherent signifying ironies that characterise his mature work (for another example, see Severs on the ramifications of the play’s repeated language of “trust”). It’s much less laborious and self-drowningly explicit about its themes than either Gaddis’s other projects of the mid-1940s (see the entry on Blague in Chetwynd&Minor, Fiction Guide) or his later efforts at full-length dramatic work (see entries on Once at Antietam and Dirty Tricks below).

Other ideas that receive complex treatment in the play’s short span include just what “identity” it is that Marlowe takes his peers to be risking by anthologization. He does not explain this directly, but addresses his fellow poets as if it’s obvious that “signing down your names” will destroy “identity” (Act III): presumably then, that identity is the name itself, “declared” by the long work of writing. Here we can see an early harbinger of Gaddis’s later discussion of how too many people want “terribly to be a writer” without “wanting to write” (Bard Q&A, 0:36), as Marlowe makes it clear that the identity follows from the action. But the unexplicated principle here is why that identity would be lost when giving the finished writing over to the anthologists, and what kind of identity would be substituted in its place. As the anthologists talk about their poets mainly in terms fungible with money, the implication seems to be that to give your work over to them is to trade being an artist for being a commodity (or at least a producer of commodities): a theme to which the mature novels will return.

Beyond this, the play illuminates Gaddis’s attitude to the Elizabethans, both in the affinity he shows for the whole era in his competent parody (and, as with the ending, affectionate ridicule), but also in the implicit value-ranking among the various poets. Marlowe is a figure of honour, Shakespeare—with his ear always out for something to write down and later claim as his own—gains the sort of affectionate respect for a guiltless game-player that Gaddis later claimed to have for JR, while Jonson’s stern pedantry is an important force only distantly aligned with “poetry.” The toddler Herrick, who gives the most vicious send-off to the anthologists and is the final figure left on the stage at the end, seems important for reasons that are not entirely clear, and it’s worth noting that he is the Elizabethan figure referred to in some of Gaddis’s other early poetry (see entry on “wait tears ill want you yet,” below). There Herrick’s particular commitment to high conceit and artifice seems important, but this isn’t much mentioned in Faire Exchange beyond his articulate-toddler stage presence being the play’s own main token of artifice and fantasy. There may be more to discover about Gaddis-on-Herrick.

Though Faire Exchange is short and frivolous, it nonetheless embodies coherent thought on topics Gaddis would subsequently do much more with. It’s competent parody rather than mere pastiche, consistently comic, and as formal poetry more fluent than a lot of Gaddis’s non-parodic poetry preserved in the archive. Indeed, no archived poem is clearly dated after it, so it may be his poetic swansong: a defence of poetry before giving it up.

Relation to Gaddis’s Published Writings: The threat of commerce to art here, along with the question of how the artist’s work conditions their identity as an artist, prefigures plots and concerns in The Recognitions, J R, and A Frolic of His Own. As Severs discusses, the warning to be careful what you sign up for is especially central to Frolic but also important in the Bast and Schepperman plots of J R, and Wyatt’s work with Recktall Brown and Basil Valentine in The Recognitions. Questions of originality and authenticity that predominate in The Recognitions (and unpublished projects of the same era like “Unfortunately”: see entry below) appear here in the contrast between Marlowe’s jealously guarded individual muse and Shakespeare’s magpie appropriation of whatever language strikes his ear. In a moment that will interest scholars of Gaddis’s vision on originality and plagiary, Marlowe’s death is lamented by Thomas Nashe, who cries “Marlowe! Thou shouldst be living at this hour. // England hath need of thee!” (Act V). Nashe thus, in the world of the play, writes the form of Wordsworth’s lament for Milton 200 years early. While the citation’s literal meaning highlights Gaddis’s vision of decadence, its proleptic plagiary also suggests (like Shakespeare’s cribbing) that the entire poetic tradition is a matter of unattributed citation and appropriation, thus undermining the idealism that Marlowe otherwise embodies (or suggesting that with him gone it’s now eternal open-season: precisely why he “shouldst be living”).

Finally, as Severs discusses, the play is not alone in Gaddis’s work in attributing a particular repugnance to the anthologist figure. Recktall Brown, the most grotesque of The Recognitions’s many grotesques, has his genesis in draft stories like “Arma Virumque” and “In Dreams I Kiss Your Hand Madam” (see entries in Chetwynd&Minor, Fiction Guide) where the relevant character being an anthologist is their defining quality. By The Recognitions his editing an anthology of poetry as a way to get close to Esme is a minor character feature, less important than his role in selling forged visual art. But Faire Exchange gives us a vantage from which to see the anthologising impulse as central rather than incidental to Brown’s character (from his rectalness to his money-minded instinct to “cooperat[e] with reality” (Recognitions 243)) and to his particular form of antagonism to Wyatt’s vision of proper art.

Other Notes and Mentions Elsewhere? In the current special issue Jeffrey Severs examines the play at length in relation to Gaddis’ personal and fictive dealings with contract throughout his life.

Thanks to Steven Moore for identifying that Gaddis likely encountered most of this particular grouping of Renaissance poets in an actual anthology: Chief Pre-Shakespearean Dramas, edited by Joseph Quincy Adams, which Gaddis alludes to in a published letter of October 5th 1942, and continued to use as he worked on The Recognitions. That novel also cites Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus directly as part of its sustained intertextual engagement with the Faust myth.

Title: Once at Antietam

Location in archive (Box.Folder): Typescripts in folders 75.3, 75.4, 75.5 (“Once at Antietam”). Relevant correspondence in folders 75.1 (“Notes from Patricia Black Gaddis”) and 75.2 (“Correspondence Relating to ‘Once at Antietam’”). Summary of a projected prose version in 31.4 (“Leather Binder”). Notes on how to incorporate into A Frolic of His Own in 73.5 (“Antietam, Fragments after Frolic”).

Date: 1960-3 (per Gaddis’ own pencil note on an archived complete typescript). The prose version summary may date to 1959: it seems to be the contents of a preserved envelope addressed to Gaddis at his Pfizer work address (the summary is folded along lines that would fit the envelope), and the stamps on the envelope are 8-cent “champions of liberty: Ernst Reuter” stamps issued in 1959.

Complete? Yes

Extent of preserved material: Completed typescripts. Fragmentary notes appear in folders of other things Gaddis worked on at the time (Sensation, J R, proto-versions of Agapē Agape), but no dedicated folders of notes or drafts.

Description: Once at Antietam is a Civil War play, familiar to many Gaddis readers from its piecemeal but substantial reproduction in A Frolic of His Own. Gaddis’s own pencil headnote to the best-preserved of the archive’s typescript versions makes clear his judgment of it:

This is the complete last draft of the play written roughly 1960-63 – better judgment finally prevailing against any effort to see it produced or even circulated. It is not to be published in whole or in part, but seen simply as a rather severe example of an amount of work and high flown ambition gone quite off the tracks.(Plato, Camus, & finally Sophocles!) – and some of its essential relationships resurrected (unrealized at the time)

reconstructedput to rest in ‘Carpenter’s Gothic’ some 20 years later. William Gaddis

This is the only piece of his archived creative writing to which Gaddis attaches an explicit “do not publish” note. Unwilling to let it stand alone, he made its raw material useful in the heavily ironizing and provisionalizing context of Frolic (to put it simply: within that novel’s world, the play was written by a fairly silly man). The archive, meanwhile, preserves almost no indexed working material beyond this final version. The summary in 31.4 confirms that it was conceived initially as a “novella, a narrative done largely in dialogue” (1), rather than as a play. Perhaps most interestingly some early letters seem to confirm that Gaddis actually sent out some drafts of this prose version: the 1960 letters responding to submissions refer to it as a “novel,” though the Antietam-labelled folders retain nothing of this apparent early prose form. By early 1961 it’s a “play” (see all letters in Gaddis Archive box 75 folder 2), which a few letters of 1961 discuss the prospect of performing. Gaddis himself describes a typical response to the initial script version from a producer in a 1961 letter: “hefting the script (without opening it), ‘Too long’” (Letters 237). Later drafts seem to have proven more appealing: Irwin Rose “ha[s] every intention of producing it” for January 1962, but needs to “line up a star for it== and raise the necessary capital.” But then he would “need a more finished script than I read a couple of months ago […] I trust you’ve made lots of progress with it since.” While Gaddis did end up with a “complete last draft” by 1963, there was no progress on performance.

The main interest in what is preserved—a complete three-act play of 180 typescript pages—is seeing what did not make it into Frolic. That novel mainly reproduces material about the play’s central figure Thomas from Acts 1 and 2, which still make the basic plot clear enough: Thomas has come back to his family’s disappointing inheritance after time abroad in France, and, forced from South to North by the inherited business role as the Civil War gets going, he ends up sending up substitutes to fight for him on both the Union and the Confederate sides. A young man who attacked Thomas in the street is one of the substitutes, while unknown to him his feeble brother William is the other.8 They die on the same battlefield at Antietam, and the delayed realization of this puts Thomas into an existential breakdown, whose terms have been conditioned throughout the play by his extended philosophical dialogues with Kane, a roving philosopher, and Bagby, his cynical opportunist of a subordinate. His mother and his paramour Giulielma endure and register his failings with passive lachrymosity. Their lamentations are one of the main elements (along with lots of North/South culture-theorising) of Acts 1 and 2 that Gaddis did not import into Frolic, where Giulielma serves mainly as a hinge to contrast Oscar’s claims for her delicate seriousness in his play with the film adaptation’s use of her character to get actress Anja Frika naked on screen.

The final Act 3 is referred to frequently throughout Frolic,9 but barely reproduced on the page. The most specific thing that the novel tells us about it is that Oscar is especially proud of the way he adapted “Crito,” the final Socratic debate, into the scene where Thomas comes to plead with Kane to escape prison. In the real play, this Crito adaptation is a perfunctory two pages with none of the original’s complex dealings with the limits of reason in the face of imminent death (which Gaddis does foreground in his other explicit citation of “Crito,” almost forty years later in Agapē Agape). The final act has four scenes: a longer one in which Bagby convinces Thomas to sign an oath of allegiance and distance himself from Kane (whose philosophical integrity has led him to be charged with treason), two shorter scenes, in which Thomas plays failing Crito to Kane’s resolute Socrates and then goes home to reconnect with his mother, and a final scene in which the discovery of the double substitute-death sends Thomas to the brink of madness, ending on his sense of being a ghost, which leads to him attempting to shoot his returning runaway slave with a decrepit shotgun that explodes at the breech and leaves him not only ghostly but blind.

The prose version’s projected plot differs slightly from what ended up in play form, and it gives a useful gloss on how Gaddis conceived of the story’s implications. In his view, it “develops and resolves a single point : what courage is in the life of a man forced by circumstances to make decisions for himself which, by involving others in what is really his own destruction, result in his spiritual suicide” (1). The narrative of substitutes for the same man killing each other in battle “makes it possible for the protagonist, Thomas, to in effect meet himself in battle and by his own hand be slain, in a plausible portrayal of man’s war with himself” (1). Its opening would have been very similar to the play, differing only in that the first substitute would not have been Thomas’s own brother but his wife’s. In the second half, though, Thomas would have spent the latter parts of the war stuck offshore because of split allegiances and port machinations. Kane would have been much less significant, and the ending would have seen John Israel return as the bearer of the news of William’s death, having buried him himself while working as a battlefield gravedigger. Thomas’s final blindness, meanwhile, would have been deliberately self-inflicted as a combination of self-punishment and insurance-money grab, as the $10,000 from his policy against such injury would set him up free of inheritance, able to go on and live his life on modest but more independent, less haunted terms.

Analysis: Gaddis gives a dismayed verdict on his first completed version in a 1961 letter: recalling “enraptured work on a play which, until I finished it and reread it, seemed to me quite great. Now it reads heavy-handed, obvious, over-explained, oppressive” (Letters 242). It’s unclear whether he thought his further work of 1962 had improved things, but “last draft” Antietam is indeed turgid reading, even more to read through as a whole than in the excerpt-contrastive setting of A Frolic of His Own. As Gaddis himself notes in his headnote, it contains a lot of undigested citation and working through of ideas from various philosophers (the sections on Rousseau and references to Plato and Socrates make it into Frolic, but there are long rehearsals of themes from Vaihinger, Camus, and others that don’t). Frolic makes this into a witty meditation on the legal status of originality: Antietam does not. Its main interest to Gaddis scholars will thus be not as a comparable completed artwork to his novels—despite its being (along with Dirty Tricks) the fullest-scaled of his unpublished works—but rather as an index of his reading and philosophical influences at a very specific time in his career.10

On a formal level, the excerpts in Frolic already convey most of what can be discovered from Antietam about how Gaddis’s dramatic work illuminates his innovations in prose. What most stands out upon restoring the play to its original place in Gaddis’s development (before its role in Frolic) is its almost total humourlessness: working on this in parallel with the early versions of J R may have helped Gaddis isolate, and see the value of, and hone, the relentless comedy of that novel.

Explicitness is another vice that Antietam embodies so fully that it helps reveal the virtue of Gaddis’s other work. The material on justice here paints in all the background for that theme’s workings in Frolic, while the material on doubt, freedom, responsibility, obligation, and so on provides a useful manual for identifying Gaddis’s consistent interest in questions of existential ethics throughout his fiction. When Thomas discusses “the… step in the dark, where chance becomes king. The… terrifying freedom of the blind…” (III-iii-6-169) one scene before he himself ends the play blind and with none of his old social structures to keep him anything but “free” in the “terrifying” “dark,” the writing is unsubtle enough to deaden the themes’ dramatic interest. It does, though, make clear the specific philosophical questions Gaddis cared about and that continued to animate his fiction even as he learned to address them without just stenographizing his favourite philosophers.

Relation to Gaddis’s Published Writings: Almost half the play is reproduced in some form (seemingly unedited where reproduced) in A Frolic of His Own. As notes on the proto-J R novel project Sensation establish, some scenes of Antietam (most notably the memory of a pheasant shoot) were initially meant to overlap with scenes in Sensation, which featured prototypes for J R characters (see entry on Sensation in Chetwynd&Minor, Fiction Guide).

Elsewhere, I myself note the importance of the play’s frequent references to Rousseau for thinking about Gaddis’s fiction’s attitude to education (“Ford Foundation Fiasco” fn11), while in the present special journal issue, John Soutter touches on the way that its many allusions to Vaihinger (which unlike the Rousseau passages were not included in A Frolic of His Own) align it with Carpenter’s Gothic’s explicit themes of living by fictions and as-ifs. This theme also organizes the unproduced screenplay Dirty Tricks (see entry below).

Gaddis’s retrospective headnote, meanwhile, insists on a link he had not himself initially perceived between “some of its essential relationships” and Carpenter’s Gothic. The thematic connections of Vaihingerian fictionalism and “as-ifness” that Soutter’s work highlights don’t seem to cover character-level “relationships,” and so to identify the links Gaddis belatedly recognised can only be a speculative project. Three particular possibilities may be worth considering: the debates between fiction-wielders and thoroughgoing cynics at the start of Antietam’s Act 3 recur in McCandless’ arguments on the topic with both Liz and Lester. The family dynamics of thwarted inheritance play out in both texts through the figure of the passive brother persuaded too passively to go where he dies. And the fragile beautiful woman going catatonic from the neglect of a promising but self-involved man also organizes both texts, though Liz in Carpenter’s Gothic is a far more central and organizing figure than Giulielma.

Thomas’s proposed ending in the prose version seems aligned with The Recognitions’ emphasis on choosing to “live deliberately” as a viable narrative resolution. That the prose version was planned to be “largely in dialogue” indicates that Gaddis was already thinking away from the narrator-driven form of The Recognitions, toward the talk-heavy style of his later works, ratifying the connection between those and Gaddis’s drama work.

Other Notes and Mentions Elsewhere? Gaddis’s letters record him considering returning to Antietam to turn it (back) into a novel in the aftermath of J R when for almost five years he was without a major project to work on. Letters in both 1976 and 1979 mention this plan, and that Gaddis had run it by J R’s publisher with unenthusiastic response (see Letters 314, 346). The plans to base Fictions (see entry in Chetwynd&Minor, Fiction Guide) around either Antietam or Dirty Tricks may have begun after Gaddis gave up on the idea of trying to straightforwardly novelise Antietam (as he also gave up on novelising Dirty Tricks). I have not found any archival trace of novelised Antietam drafts.

Jason Arthur identifies the root of Antietam’s double-death plot in “Gaddis’ ancestor Solomon Meredith” (fn18). The archive, meanwhile, preserves an undated letter from Gaddis’s then-wife Patricia Black Gaddis giving details of the case of Colonel Frank Coxe, which she has researched in the archives of the Pennsylvania Historical Society. She quotes:

The soldiers who served as substitutes for Coxe in the Union & Confed army were killed in the same battle & Mr. Coxe ever afterward considered himself responsible for their deaths. In later years he grew fanciful enough to imagine that the two killed each other.11

This seems a direct source for the play’s basic plot. There is no indication that Gaddis himself saw any more of those archives than his wife reported to him.

Since so much of the play is reproduced in A Frolic of His Own, much criticism on that novel addresses the play material in some form or other. The fullest of these engagements is Johan Thielemans’s “Once at Antietam: A Lost Play Recovered: On A Frolic of His Own.” Judgments on the quality of the play (as it functions within Frolic) come from Arthur—“pallid”—Richard Eldridge and Paul Cohen—“self-important, emptily derivative” (47)—and Robert Weisberg: “melodramatic… at the very least, bad Faulkner… if Joyce were to capture a satirist capturing how Eliot, in his own homage to Dickens (‘he do the police in different voices’) would rewrite Absalom Absalom!” (447). This stress on parodic impersonation is ironic in the light of Gaddis simply reproducing a play that he himself had written with no parodic intent. The note debarring it from eventual publication suggests that when he reproduced it unedited in the very comical Frolic, he presumed readers would readily judge it the same way his note does: as accidentally comical material.

Title(s): Dirty Tricks / One Fine Day / Fawkes / The Blood in the Red White and Blue

Location in archive (Box.Folder): Full screenplays, extended “Film Treatment,” and notes, plus some correspondence, in 86.6 and 86.7 (Drama – “One Fine Day”); notes toward a prose fiction version in 82.10 (“Notes, Possible Projects Aborted”). Mentions in other correspondence about films.

Date: 1968-78 based on document dates, possibly starting earlier.

Complete? Yes

Extent of preserved material: In 86.6, nineteen-page “Film Treatment” for One Fine Day, complete draft screenplay of Fawkes (a version attributed also to “H Bloomstein”—Gaddis’s agent Candida Donadio’s screenwriter husband—with a pencil note to his name specifying “bad draft with”), and correspondence with producers (mainly about One Fine Day). In 86.7, One Fine Day treatment again, and full screenplay (117 pages). Complete draft screenplay of Dirty Tricks (143 pages) in Steven Moore collection (also at Olin Library special collections: awaiting processing for box/folder number). 10-15 pages of notes for prose version to be called The Blood in the Red White and Blue in 82.10.

Description: In a 1978 letter to the producer Jack Gold about turning J R into a film, Gaddis notes that

despite the formats, the novel JR is essentially more cinematic than a screenplay I worked on called DIRTY TRICKS, which I think my agent has sent along to you to look at. It’s an idea I’m still quite attached to (a western parody of the Faust story), but as it stands now seems to me somewhat static in its development compared to J R. (letter to Gold)

This “parody” had been circulated to studios as early as February 1968 under the name One Fine Day (the title of the “Film Treatment” archived here), as indicated by archived rejection letters (some of which refer to it as a play rather than a screenplay). A further draft, titled Fawkes, with indications of co-writing and labelled as a “bad draft” (see above) is also filed, but without clear indications as to date. The fullest feedback in a letter comes from 1973, when it’s still referred to as One Fine Day. Dirty Tricks, then, was presumably a title invented between 1973 and the final publication of J R, which attributes a project by that name to the character Schramm, though there it “didn’t even have his name on it” (J R 396).12 Gibbs’ brief description of Schramm’s film gives it a similar frame to Gaddis’ actual screenplay—“God damned general in there above the battle taking bets just like the Lord”—though Schramm’s is explained as an allegorization of his actual military experience being abandoned to defend a town alone.

The following description and analysis mainly refer to the archived screenplay titled Dirty Tricks, on the basis that it seems to date latest and so to be the closest to a “final” version. I have been unable to do a fine-grained comparison of the differences between Fawkes, One Fine Day, and Dirty Tricks but their basic plots all follow the same outline as the “Film Treatment” of One Fine Day, and there seem to be few substantially different scenes in each. Closer comparative study in future may allow for a more reliable composition history than I have been able to establish.

The final complicating version is a set of notes toward a prose version, under the title The Blood in the Red, White, and Blue. It is possible that this is where the project began, in the mid-1960s, but various plans here like “restore the jewel scene” or “turn all the sequences upside-down” imply that Gaddis is working from a prior version. A 1976 letter to his agent talks about selling the “comparatively short and simpler western” as the successor novel to J R (Letters 318). He also mentions in a brief interview in J R’s immediate aftermath that his next fiction project will be a western, since “every American writer should have a Western in them” (Sheppard). This would explain and perhaps date the archived notes: he does not seem ever to have progressed to a prose draft. In the absence of any evidence for work on a prose version before J R was published, it makes most sense to see The Blood… as an intended novelization (with many different emphases) of the earlier “parody” film-script.

Pre-J R letters, whether published or archived, rarely mention the project, and hence don’t clarify the chronology or version-history. It even remains unclear how Gaddis came to the project in the first place. It does seem to date to the mid-1960s when progress on J R was at a nadir, and the (likely early) collaboration with agent Candida Donadio’s husband on a draft suggests some degree of outside intervention in getting the project started. The timeline allows for this to have been something Gaddis worked on with his 1967 grant from the National Endowment of the Arts. Compared to these mysterious origins, the archive clarifies Gaddis’s attitude and reasons for finally leaving the project behind. The final note on what is presumably his last page of Blood notes renders the verdict:

This is certainly not a book I would recommend to anyone of wit or intelligence; for the straight goods they should go direct to Bentham, Vaihinger, & Morse Peckham.13 For the vehicle, my regard for the western as an inately [sic] juvenile form grew, through daily labouring its limitations, to a kind of loathing.

Referring to it as a “book” suggests more progress than the archive leaves visible, but Gaddis goes on to contrast this project’s effort unfavourably with even the struggle to finish J R: “I have approached my two longer novels with an enthusiasm bordering on obsession” but with this one he has had to fight through that loathing, and—for all that he told Gold he was “still quite attached to” the basic idea—he could not summon the “enthusiasm” to follow through to a drafted novel.

The plot, set in the unspecified American West in the wake of the Civil War, follows the outcomes of a wager between “Slade” (the story’s Mephistopheles) and “The General” (the story’s God) about whether Slade can, by promises and guidance alone, corrupt with ambition the General’s protégé Fawkes, chief lawyer in their frontier town. The General believes that men tend toward the good and a higher purpose, Slade that they all sink to the same level when it would serve their selfish ends. The General has predetermined that Fawkes will rise nobly to high office: Slade sets about the task of corrupting Fawkes by promising him that same destiny. After a demonstration of his manipulative powers by getting two local criminals who have escaped justice to kill each other in a fight over cards, Slade wins Fawkes’s trust, leading him into indulgences like the seduction of an innocent young girl called Margaret, and the pursuit of political influence that leads him to ignore the work of defending the innocent on which his reputation has been built. His lay preaching slides gradually into law-and-order stump campaigning.

Slade himself seduces Margaret’s mentor Ann while trying to stop Fawkes giving up his political striving for love with Margaret. When Fawkes’s negligence leaves his admiring young law clerk unable to stop the hanging of a child, the townspeople start to turn on Fawkes, and when he throws off the pregnant Margaret to focus on campaigning for an election, her brother Billy, a locally stationed solider, vows to kill him. Slade, fresh from contriving the death of one of the child-hanging jurors, is supernaturally cognisant that Billy won’t go through with it, but nonetheless leads the two into a confrontation that sees Fawkes kill Billy in “self-defence.” When Fawkes returns to Margaret, she seems insane and he must leave, but we find out immediately afterward that on Ann’s advice she has feigned madness to cast Fawkes off. Suspicious of Slade’s role in all this, and having heard that The General did nothing for his “mad” lover, Fawkes wins his election among an increasingly hostile public, but brings his gun to town on the day of his taking up the new role. On rumours of a showdown between Fawkes and Slade the townspeople assemble, but as Slade is standing near The General, when Fawkes fires, it is The General who goes down… Whether he meant it, whether this means Slade or The General won their wager, are left to be resolved, but Fawkes is killed. For resolution’s sake, Slade offers another wager on the same terms as he draws The General’s bleeding attention to the young idealistic law clerk.

While one of the rejection letters states that Gaddis adds nothing to the many extant pseudo-Fausts, the screenplay does make some notable departures from the Goethian source. For example, the original’s wager is between Faust himself and Mephistopheles, rather than the demon and God about Faust, and in the original Margaret’s madness is real rather than feigned. Between direct echo (a black dog that follows Faust/Fawkes into his rooms) and difference (Fawkes is a lawyer and preacher, not a scholar), the screenplay is clearly derived from its source material, but not coherent enough in its departures to achieve a distinctively angled commentary on it. The 1973 letter of feedback is mainly focused on ways to make it less derivatively Faustian (mainly to do with making Slade more heroic).14 Future tracing of the exact relationships to Faust will be necessary to establish exactly how the screenplay builds on and modulates the Goethian ideas, but the basic shift in emphasis seems to be in the closer place of The General to the action than God in the original: close enough to not only be disappointed, but attacked, thus expanding the potential reach of human will, but also the degree to which it can transgress into distortion and corruption.

For all that Gaddis told Gold the screenplay was less “cinematic” than J R it is also not especially “literary.” There are extended philosophical conversations, but by contrast to Gaddis’s prior attempt at full-length drama in Once at Antietam the language is naturalistic, the pace more dynamic, and the visual staging elements far more fully worked out and dramatically essential. Indeed, one of the more unique departures here from Gaddis’s usual style are a number of low-dialogue scenes at a Brothel where the imagery is hellishly surreal to a greater degree than anywhere else in Gaddis’s fiction. See for example, the following passage of stage direction without dialogue:

EXTREME CLOSE SHOT OF FIRST WHORE, ALMOST IN REPOSE

Sound level recedes somewhat. Her hand enters shot, middle finger slowly wipes blood from her face, and is held before her lips as she stares fixedly downscreen at FAWKES. Finger slowly comes to her lips and she touches it with tip of tongue. CAMERA TILTS DOWN TO FOLLOW HER BOWING HEAD OVER DAZED FACE OF FAWKES STARING UP. She touches tip of finger to his lips. His hand rises, pulls her down. Her hair cascades over them filling shot. There is an ABRUPT HIGH-PITCHED YELP as we

CUT TO:

SHOT OF DOG WITH FIRST BOY CLINGING TO ITS HIND FOOT (WHICH BOY HAS JUST BITTEN). (47)

On a second visit to the brothel, we see that “DOG has been decorated as bride” (129). A combination of lurid cliché and genuine strangeness, the brothel-scene visuals show how Gaddis (perhaps in collaboration with his co-drafter Bloomfield) was occasionally working with visual direction alone, rather than just as a complement to dialogue.15

The notes toward a prose version give fuller and more explicit thematic glosses than the screenplay, both in indicating the prose version’s own emphases, and how it might have to differ from the prior version to achieve them. For example, in the original the boy who gets hanged is part native part Mexican, helping to explain the town’s callous willingness to see him die, and Gaddis then makes early notes for the prose version that Margaret herself should be Mexican: “Great point this approach offers is the uncongeniality of her church & his […] so we have the whole contrast of Prot. ‘free will’ & responsibility vs. intervention (M can’t get it through her head why the Gen won’t intervene).” A number of notes thus refer to her as “Margerita.” Fawkes and Slade, meanwhile, would also have been characterised differently: rather than energetic and promising, Fawkes in this version would have been “an equivalent of a modern lost alienated man, burned out,” and have returned somewhat to his Goethian origins as a scholar: “that F has studied and come to the end of it (Knowledge V).” Slade would therefore not be misdirecting his natural ambitions, but restoring energy and vitality to him just to destroy him more fully: if Fawkes having studied his way to resignation could lament “how I ended up here,” Slade would promise rejuvenation: “Ended up? You’ve just begun.” The notes also suggest getting rid of the initial scene that explains the wager, and saving for the end of the novel the revelation that Fawkes’s life has been ruined for a mere bet. The notes toward the prose version, then, give us a sense of where Gaddis found his screenplay thematically lacking, and point the way to a slightly more definite appropriation of Faust for Gaddis’s own argumentative purposes. As his final note indicates, though, his distaste for having to fit everything into the Western genre seems to have put paid to that ambition, leaving him to pursue some of his intended themes in Carpenter’s Gothic.

Analysis: Gaddis’s departures from his Faust source have their most coherent rhetorical and philosophical upshot in the screenplay’s treatment of free will. While much of its material under that heading simply rehearses existing ideas, Dirty Tricks makes a distinct contribution in exploring manipulation as a category that mediates between and exceeds the standard poles of “destination” and “individual will.” Notes toward the prose version show that Gaddis intended to centralise this further, with “S promoting this […] idea that you make yr own destiny while really he is making it,” while another note more openly questions “why have faith with possibility of failure when things can be manipulated and the end made certain (v V Means & Ends).”16 Even before this planned prose elaboration, manipulation’s relation to will animates some of the screenplay’s most intriguing moments.

These mostly hinge on Slade’s manipulations distorting the destined paths that The General has laid. Their wager, after all, is not about whether or not Fawkes is ambitious for high office, but about whether merely by making him conscious of this ambition Slade can manipulate him to “rot” and turn against The General’s pre-laid destiny. The moral relation between destiny and will for the same end goal (here “high office”) is explained through the General’s “You’d ask me to change the course of things now? For a man who’s tried to step in and take them into his own hands? All that would have come to him anyhow” (127). Fawkes’s resort to his “own hands” represents such a betrayal to the General that he will not even defend Fawkes against Slade.

The language of “chance” is where many of these complexities are worked out. The General looks down on “A man who’s been given every chance! Suddenly seizing everything for himself, any way he could get it! Everything that was already there waiting for him, on the course I had laid out for him from the start” (128). “Every chance” is exactly what The General did not give Fawkes, and what Slade, in persuading him to act on human ambition, has given him: if anything he takes chance from The General, who wants to have it tightly owned and controlled. Yet despite the terms of The General’s blame, Fawkes himself seems unaware that he has chosen to enter the realm of chance: he breaks with Margaret (thus ratifying the moral corruption Slade has promised us) by insisting that “You can’t leave a campaign for high office to chance” (87). This puts his moral failing into the realm of choice rather than destiny, as he appeals to chance-reduction to deliberately but unconsciously put himself on the side of chance (outside of sure destiny). Slade’s manipulation pushes Fawkes to take chances and reduce fate, even as Slade himself sees this choice as an inevitability in any human given ambition. Slade’s irony even allows him to manipulate Fawkes precisely by appealing to the fixity of the General’s will: when Fawkes briefly contemplates intervening to save the boy from hanging (which would revert to the General’s conception of him and thwart Slade’s), Slade gets Fawkes to stay in the realm of choice by encouraging him to give it up: “And how do you know the General hasn’t already decided to extend it? Do you think you and this clerk can change his mind, whatever he’s decided? Has anyone ever? No” (101). These tightly-wound ironies represent a real refinement of the simple oppositions that usually govern free-will discourse.

The ironies grow outward from the central triangle along with Slade’s influence in the town: the jury that convicts the boy, for example, concur among themselves that judging before they hear evidence is better aligned with God’s ordained plan for justice: “don’t you worry… He’ll get a fair trial, all right, then he’ll hang” (93): the trial is “our chance to” play a role in justice’s predetermined progress. Slade helps manipulate Fawkes’s popularity, meanwhile, by constructing falsely inevitable futures from false pasts, reorganizing the collective memory of the bar shooting scene so that those who were present believe it was Fawkes who set the action in motion. One such bystander says that Fawkes’s extra-judicial arranging of justice in those shootings is “The Lord’s truth” (a repeated phrase throughout the screenplay), whereas this memory is very specifically Slade’s (fabricated, Lord-spiting) truth. The bystanders then credit Fawkes for a great understanding of “human nature” in manipulating the killers, even as it is precisely Slade’s insight into their human cognitive biases that allows him to build their realities for them this way.17

Slade is even able to make religious belief itself a tool of manipulation: when he needs Fawkes to sign a form that will free Ann for marriage, Fawkes demurs because “I’ll be swearing to something I know nothing about.” But Slade persists: “How many times have you stood in your pulpit, preaching sworn sermons about God’s purposes, some great design? Things you certainly know less about” (65). Slade himself knowsThe General/God’s “design” and is able to manipulate Fawkes away from it precisely by appealing to its unknowability. This passage also highlights an ontological complexity that the screenplay doesn’t fully pursue, which is that for all that The General is fully analogized to God (stressing that there was nothing to this town before he created it, and so on), his town still contains a Christian church devoted to worshipping that God, and its people attribute everything that happens to that God’s design, even as they also acknowledge the General’s determining power. That the story’s allegorical God might be subject to the whims of his own God raises a further question about whether Slade’s victory over The General might still be within the intended destiny established by the actual Christian God beyond The General. Gaddis’s prose-version plan to add the wrinkle of a Catholic/Protestant conflict between visions of will by making Margaret into Mexican Margarita suggests that this multi-dimensional religious ontology could have become even more internecine, with even more complex consequences for the morality of will.

The scene of fullest irony about will and determination, and fullest departure from Faust, comes when Slade decides to arrange the death of one of the jurors. Seeing The General’s carriage approaching in the distance, he throws fool’s gold into the road and challenges the juror to collect: when the juror is run down by the carriage, Slade has successfully shown not only that he can manipulate humans and the paths they take, but also that he is thereby capable of making The General himself into a killer rather than a helper. The General is unable to stop the carriage, does not subsequently attempt to punish Slade, and can only offer a passive look of “angry rebuke” from the carriage window as he rolls on down his own predestined path. Thus Slade’s manipulation can make “chance” and “rot” of even The General’s own course, and so turns out to be a greater force than either human will or non-intervening predestination alone. The townspeople, of course, attribute the outcome to destiny: the General would never choose to hurt anyone, but “when the Lord calls, we come, and that’s all they is to it” (116). Yet again, the irony is that it is not The Lord who has been calling these shots.

The project also gives a distinct articulation of the value-system attached to Gaddis’s career-long interest in “what is worth doing?” The notes toward the prose version suggest that the burnt-out Fawkes would have to face that question as directly as Gibbs does in J R. Even in the screenplay with the energetic and ambitious version of Fawkes, Slade manipulates him away from his “natural” commitment to the underdog by giving him an alternative version of “worth”: “You simply haven’t the time now. You’ve handled enough of these lost causes. Winning one more won’t help, but losing one could destroy all the others” (83). “Destroy” here puts the question in terms of the hoary old opposition between deontology and consequentialism. To a deontologist one failure while trying to do the right thing could not destroy the value of other right things done; it would only be destruction if the earlier goods were valued only for their instrumental use in achieving some further end. On that consequentialist model, it would be more “worth” avoiding the risk of marring a usefully perfect track record than attempting to add to the cumulative amount of good. Slade thus implies that the kind of “active” that Fawkes should be might involve a deliberate moral passivity, which again further complicates the issue of will, activeness, and destiny. Gaddis’s notes toward the prose version then express its entire message in the language of destruction: that “we inner-directed go wrong and destroy ourselves when we despair and go to the outer for direction.” Again the issue is not so much of the inner will, but of outsourcing your own agency to the manipulative power of the outer-directed value system. This then plays into basic perspectives on orientation toward living, as Gaddis hoped the project might express “tyranny of hope vs. V’s pessimism as positive.”

The project is also notable for its handling of female characters: Ann and Margaret in the screenplay are mainly passive seducees and sufferers, but Gaddis’s notes toward the prose version imply that he wanted to make gender more important, “That WOMEN have eventually and intuitively total control of the FICTIONS that keep things working. They know intuitively (& use accdgly) what we try to reason (& fail accordingly).” The only scene in the screenplay that expresses such control is the revelation after Fawkes leaves “mad” Margaret that she was only feigning her madness to have an excuse to get rid of him. Gaddis’s early fictions often feature a female character going mad (see entry on Blague in Chetwynd&Minor, Fiction Guide), as does his source in Faust, and Margaret’s feigning here conspicuously revises this madwoman trope in terms of female agency. It’s one of the story’s rare examples of deliberate human will exerted but unpunished, and even Slade does not seem to have access to its revelation. Even the madness scene, though, is framed in terms of the discussion of inevitability and responsibility: one of the images Margaret rants about is “that little boy we saw hanged up there, like a sign to say here’s a fork in the road when he’d already passed it” (137). The dealing with fictionalism and gender here is still, finally, subordinate to the free will thinking about what is salvageable and what is “already passed.”

At any rate, especially in contrast with J R (which it was initially drafted parallel to, cited in, and then briefly conceived as a successor to), what the Dirty Tricks project most throws into relief overall is Gaddis’s persistent interest in existential humanist questions even as he was working on his great “systems novel,” with its long legacy of antihumanist or posthumanist critical interpretation. Gaddis at one point asks in a note why Slade, with all his devilish powers, would let the people beat and torture him in the opening scenes where his previous town runs him out on a rail. Gaddis imagines rewriting the scene to more fully stress Slade’s “scorn of the mob in the midst of this agonizing torment, his almost inhuman attempt to give them the satisfaction of seeing him suffer, his contempt for his companion’s howls and pleas, his glint of cunning broken by stabs of pain, his certainty that he will come through.” While “inhuman” is the word used here, what we actually get is a devil choosing to suffer as a human, deeming that to be something “worth doing,” and so starting the whole film off on a humanist note. If Dirty Tricks were to become part of the Gaddis canon, one of its effects would surely be to move the scale on the debates between humanist and posthumanist accounts of Gaddis’s oeuvre. Gaddis himself, though, had his eyes on more than just interpretive difference as he pondered this rewrite: the “inhuman” “suffering” scene “will instantly send a producer grabbing in his mind for. Bronson, McQueen, Bogart…”

Relation to Gaddis’s Published Writings: The direct adherence to the structure and dramatis personae of Goethe’s Faust shows that Gaddis’s inspiration from that source did not dwindle after The Recognitions: for scholars looking to pursue Gaddis’s Faustian influences, this film project will be as important as his first novel.

Although it was initially written while Gaddis had J R underway—and although Gibbs in J R refers to Schramm’s “Dirty Tricks” film as “same God damned thing as all this” (396)—the screenplay illuminates that novel more through contrast than affinity. For one thing, it takes little interest in the various matters that have generally been discussed in J R under the “systems” heading: the evolving economy, networked structures of agency and influence, thoughtless subjectivities, proliferating scale, communications media, and so on. Its concerns are mainly where humanist individual matters intersect with the metaphysical, rooted centuries earlier in Faust’s core relationships and making less effort to update them to a contemporary vantage than The Recognitions does. So conspicuous is this distinction from J R’s basic material that this film project might have functioned as a way for Gaddis to clear his head from that novel’s preoccupations, just as film work gave him some respite from literary composition.

Nonetheless, the notes do establish connections with J R, though more explicitly in those toward prose-version Blood… that likely came after that novel. One note, for example, brings together characters from each project under an existential banner: “the problem of indecision & eventual paralysis of the will // how Fawkes & Gibbs (what is (not) worth doing) relate.” “What is worth doing?” has long been acknowledged as one of the central questions that spans Gaddis’s career, and here he makes it something that Slade’s manipulation of Fawkes can play upon. If “indecision” and “paralysis” of the will are individual psychological matters, they still play an important part in J R, where they are ranged against the seemingly irresistible tide of forces that overwhelm individual agency, a dynamic thematised in the western as well, where the individual will is up against predetermination, manipulation, and (whether you agree with Slade or the General, they each think this matters more than individual character) “human nature.” When Gibbs identifies “all this” that Schramm was up against and that his western was about, the referent seems to be that Schramm was left on his own “holding the point” of a strategically important village while those who were supposed to help him abandoned him, and those with power stood “above the battle taking bets” like The General in the screenplay leaving Fawkes to face Slade’s manipulations undefended. What is Schramm defending, allegorically? The world of thought as valued by him, Gibbs, perhaps Eigen, and hardly anyone else they know. A note toward the prose-version further echoes J R in specifying that Slade’s attack on “we inner-directed” is “what America is going to be all about”: if Major Hyde in J R will frequently tell us that his rank materialism is “what America’s all about” in the mid-20th century, Gaddis’s “going to be” note figures his existential-metaphysical relocated-German-Faust western as in part a national origin story. This would identify the American lineage not as mere Hyde-style financial greed, but in the lineage of skilled manipulators turning ambivalent people toward ambition and greed out of sheer contempt for human nature. This concern with origins thus frames the western both as an ideological prequel to J R, and as part of the tradition of 1960s Western rewrites (in literature and film) that parodically reinterpret American origin-myths, running through the decade from EL Doctorow’s Welcome to Hard Times (1960) to Burt Kennedy’s Support Your Local Sheriff! (1969).

Frequent discussions of the role of fictions in living run throughout the script, and are an even more central and explicit concern in the notes toward the prose version. Gaddis wonders of Slade’s invigorating but misleading fictions “when does the fiction become a lie,” while some of the rare drafted dialogue for the prose version would have Slade himself making the case to Fawkes that “a hypothesis wants to be proved, is waiting to be proved […] a fiction doesn’t have to be proved: it just has to work.” These concerns are picked up directly in Carpenter’s Gothic. The association Gaddis makes in his notes between women who “control” fictions and the men who don’t and “fail accordingly” maps onto that novel’s alignment of McCandless against useful fiction and Liz in favour of it. These questions were also central to Gaddis’s superceded proto-project of 1978-81, Fictions, which evolved into Carpenter’s Gothic and A Frolic of His Own (see entry on Fictions in Chetwynd&Minor, Fiction Guide). As John Soutter’s contribution to the current special journal issue makes clear, Gaddis’s Vaihingerian interest in what role conscious fiction-investment should play in our lives is not isolated to his explicit mentions of Vaihinger in these notes, but runs throughout his career.

The black dog wandering through the hellish costumed brothel scenes, ending up “decorated as bride,” may be a cousin of the black dog with painted nails that wanders through Carpenter’s Gothic.

Meanwhile, as Slade’s undermining of Fawkes and The General happens through his manipulation and perverting of their institutional relations to the law and to religion respectively, there’s a forward look here to Gaddis’s sceptical institutional visions of religion and law in Carpenter’s Gothic and Frolic. The repeated vocabulary of “Justice” here also looks forward to Frolic. The contrast of Slade’s and The General’s earthly-hellish and Godly-ideal visions works as a quite direct gloss on that novel’s famous opening lines: “You get justice in the next world, in this world you have the law” (Frolic 3).

The completed screenplay being Gaddis’s most extended work for the film format, it will be of interest for precise identifications of how his prose forms from J R onward engage with the influence of non-literary media.

Other Notes and Mentions Elsewhere? Gaddis discusses the project in published Letters, on pages 297-98, 299, and 318. As discussed above, Dirty Tricks with elements of its plot intact is a film written by the dead writer Schramm in J R (396). The Blood in the Red, White, and Blue ends up as the name of the film that adapts (and travesties) Oscar’s (and Gaddis’s) play Once at Antietam in A Frolic of his Own. The novel’s film, unlike its play, bears no relation to the work Gaddis himself did under that title.

Title: The Secret History of the Player Piano

Location in archive (Box.Folder): 86:8 (“The Secret History of the Player Piano”)

Date: Unclear, but after J R’s publication since it contains pages from published J R – filed with a presumably later Gaddis note saying “70s?” Peripheral filed material indicates 1977.18

Complete? No

Extent of preserved material: 150-ish pages chopped from J R with nondialogue elements crossed out. Brief undated correspondence regarding play. One-page cover note on what the material is and intentions for developing it. Typed and handwritten notes on extra plot ideas. Supplemental notes on what Gaddis would do to better suit the material to the stage. Three pages of “problems” in plotting and rhetoric that would need to be resolved in the process of creating a standalone script.