William Gaddis’s Unpublished Stories and Novel-Prototypes: An Archival Guide

A survey of Gaddis’s known and archived unpublished prose fiction, particularly short stories from before The Recognitions and incomplete forerunner projects for his eventually published novels. Those include the two aborted novels that evolved into The Recognitions, notes toward a projected novel about filmmaking that provided foundational material for Carpenter’s Gothic and A Frolic of His Own, and more. Each entry contains archival location information, historical information, description and analysis of the archived work, and discussion of any connection to the eventually published fiction.

Various materials from the Gaddis Archive by William Gaddis, Copyright © 2024 The Estate of William Gaddis, used by permission of the Wylie Literary Agency (UK) Limited Due to the copyrighted archival material reproduced here, this article is published under a stricter version of open access than the usual Electronic Book Review article: a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 license. All reproductions of material published here must be cited; no part of the article or its quoted material may be reproduced for commercial purposes; and the materials may not be repurposed and recombined with other material except in direct academic citation – https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

In a late-career interview, William Gaddis clarifies that we should not think of him as a writer of prose fiction, but specifically of novels, which “are my craft, my calling, if you like. That’s why I’m not at all interested in anything else like stories” (in Ingendaay). At around the same time he demurs from work in any other genre: “I don’t want to do something half-heartedly that I don’t know anything about” (in “Eine Vorlorene Schlacht”). The short story form is something for which he claims no talent, and he abandoned it early. Gaddis’s comprehensive archive bears this out: there is no preserved short story that can be definitely dated to after 1956, in the year after he published his first novel.

1955, with The Recognitions at the publishers and no longer project yet begun, was perhaps the strangest and most multi-genre year of Gaddis’s writing life, as the archive reveals him working on popular non-fiction like an economics of mini-golf for Sports Illustrated, on proposals and scripts for short TV drama (see Chetwynd, Nonprose Guide), and—having seemingly attempted almost nothing in the form since 19471—a return to short stories. The preserved short stories from this era (notably “No Sale,” “The Coke Finish,” and an early prose draft of what became a TV proposal, “The Black King and the White Bishop”) are all distinctively commercial fiction modelled on what Gaddis seems to have thought was selling. His earlier short stories can each be triangulated between their three most common modes: taciturn Southwestern tales of rural epiphany, stories of fops or lightly occult eccentrics wandering New York until a cab hits them, or pseudo-existential recountings of numbly murdered strangers. By contrast, the 1954-5 stories are set in the present, in business contexts, and end with clearly stated morals delivered by characters winking as they say them. The difference from The Recognitions hardly needs spelling out. Submitted under Gaddis’s name, they are often accompanied by lists of potential pseudonyms to publish under (“John Trask” appears most often), implying that he saw them as hackwork not meant to tarnish his novelistic reputation. But these pandering stories were rejected wherever Gaddis sent them, just as had been his stories of the 1940s, and after these 1955 failures he seems to fully abandon the form. From here on, there would be attempts at dramatic work (much completed, all rejected), and there would be the novels, each of which grows (sometimes at decades’ remove) out of some distinct abortive prototype.

If Gaddis’s short fiction is mostly pre-Recognitions apprentice work, nonetheless there is a great deal of it fully preserved, and that archive offers both further understanding of his interests and development as a novelist-not-short-fiction-writer, and a useful sociological archive of what creative writing in the 1940s looked like, across the classroom, the working desk, and the publishing institutions.

The current document offers a comprehensive guide to Gaddis’s unpublished prose fiction (with the proviso that more undiscovered material may yet be lurking in the less item-indexed corners of the archive).2 That includes extended description and analysis of four projects that eventually became The Recognitions, J R, and A Frolic of His Own (minor elements in each prefigure Carpenter’s Gothic and Agapē Agape, but—at least after Agapē became a planned fiction—neither absorbed a truly distinct project). It includes briefer information about and descriptions of almost fifty complete stories, and of nine stories with significant drafts and planning material that are either materially incomplete, or filed as “unfinished” (by Gaddis himself) even though the existing drafts seem self-contained.

We omit, however, any short story project for which no more than one complete drafted page exists. There are a number of such abortive note-plans or single-page fragments throughout the archive, most prolifically in folders 81.8 and 81.9 (Short Fiction: “Early-Loose”), 82:10 (Short Fiction: “Notes, Possible Projects Aborted”) and 82.27 (Short Fiction: “Unfinished”). These fragments have titles like “In Sickness and in Health,” “The First Papers of the Homarus Society,” “The Fortune Teller,” “The Bloody Horse,” “Paul’s Child,” and “The Junk Hustler,” and sometimes come with notes that explain thematic preoccupations even if they never became completed drafts. Sometimes, as with the single-page typescript that begins “Evidently they were on their guard,” the fragment seems to be either self-contained or the final page of a draft missing the rest of its pages. And these splinters may sometimes be of interest for their theme and style alone (the “on their guard” page, for example, is perhaps the most condensed epitome of Gaddis’s cod-existential mode, containing in ¾ of a page the fear of exposure, an all-saturating feeling of persecution, cold murder contemplated as the solution to a seemingly insignificant problem, and the absurdly uncommensurated choice between going out to commit that murder and staying in to read a stack of old newspapers). But whatever interest these fragments may have in themselves or as illuminations of the more complete stories, they are too many, disparate, and unmoored for us to usefully itemise here.

While most but not all of the fuller material of stories completed or significantly worked on is identified and located by the Gaddis archive’s recently updated finding aid, and most of the individual stories have their own dedicated folder, we also here identify stories with no archival index, and address instances where material for one story can be found in numerous different folders. We hope that the current guide will give potential researchers enough information to know which particular stories and documents they might want to consult, and where to find them. While we don’t attempt anything like a full literary or research analysis of any of Gaddis’s unpublished fiction here, we do aim to identify in each case the interest of themes, techniques, and explicit connections to his published work.

A separate document in this same special journal issue constitutes a comparable guide to Gaddis’s unpublished work for non-prose media: his stage drama, his screenplays, his proposals for TV and film, and his poetry (henceforth: Chetwynd, Nonprose Guide).

A few clarifications about contents and method before the guide begins.

When we say “unpublished,” we mean what Gaddis did not publish during his lifetime. Four of the stories addressed here have subsequently been published: Crystal Alberts compiled and edited three (“Jake’s Dog,” “The Rehearsal,” and “A Father is Arrested”) for a 2004 issue of Missouri Review, while Ninth Letter and then Harper’s published a version of “In Dreams I Kiss Your Hand, Madam” in 2007 and 2008 respectively.

We do not attempt to address any of Gaddis’s Harvard Lampoon work: that was published, and remains accessible wherever the Lampoon is archived. Steven Moore has usefully identified which of the Lampoon pieces from volumes 127 and 128 (1944) were written by Gaddis, even under a pseudonym, and Moore’s personal archive at Washington University in St Louis’ Olin Special Collections Library contains copies of all this work.3 However, the methods Moore used to identify the pseudonymous authors in those editions were not possible with two other issues Gaddis was involved with (volumes 126 and 129) and so it remains unclear which pseudonymous contributions he wrote for those issues.4 In the absence of definitive information about what constitutes Gaddis’s full Lampoon oeuvre, and counting Lampoon publication as publication, we hold off from addressing any of it here.

For each entry here, we clarify the box/folder location of the material in Gaddis’s archive, attempt to date where possible, describe the basic plot of the story, and explain any significant thematic implications or writerly techniques. We then note any clear correspondence with the subsequent published fiction, or any references to the material in published criticism or Gaddis’s published letters.

We omit individual citation information for documents where the “Location in Archive” part of the relevant entry already contains sufficient Box/Folder information. We give page references only where the document itself has page numbers. References to relevant archival material without a specific entry here are endnoted. References to published interviews, studies, and so on are by author-name or parenthetical, and refer to a works-cited at the end of this document. References to published letters are by page number of the Letters volume edited by Moore.

Individual entries contain information on how the text in question relates to Gaddis’s published work; the most relevant entries for each of the published novels are as follows…

Explicit or stipulated continuities of plot and project exist for the following:

The Recognitions: “Blague,” “Ducdame / Some People Who Were Naked,” “Arma Virumque” / “In Dreams I Kiss Your Hand, Madam,” “Some People Living in a Hotel”

J R: “Sensation” / “Rose in Print”

Carpenter’s Gothic: “The Late Mr Slyke” / “Fictions”

A Frolic of His Own: “Fictions” / “Theatre” / “The Late Mr Slyke” / “Concentrate on the Real Story”

We establish looser or more general material and thematic connections for:

The Recognitions: “Art’s Place,” “At the Seawall,” “Evelyn Ex Libris,” “A Father is Arrested,” “Mr Astrakahn Says Goodnight,” “Much Virtue in If,” “Kotalik,” “No Sale,” “Social Life of a Single Man in New York,” “Where is Miss Horse?”

J R: “The Ambassadors,” “Art’s Place,” “The Coke Finish,” “Ernest and the Zeitgeist,” “The Rehearsal,” “Social Life of a Single Man in New York.”

Carpenter’s Gothic: “Concentrate on the Real Story,” “Rose in Print.”

A Frolic of His Own: “The Rehearsal.”

Agapē Agape: “Gorland at Large,” “Sensation.”

Researchers interested in seeing any of these documents should contact the Olin Special Collections library at Washington University in St Louis to arrange visiting times and item access requests.

We hope this guide will encourage more investigation of these materials and their interest for the study and understanding of Gaddis’s work.

Below, we first address the novel-prototypes, then the complete stories, then the incomplete stories.

William Gaddis’s Superseded Prototypes for Novels (Chronological)

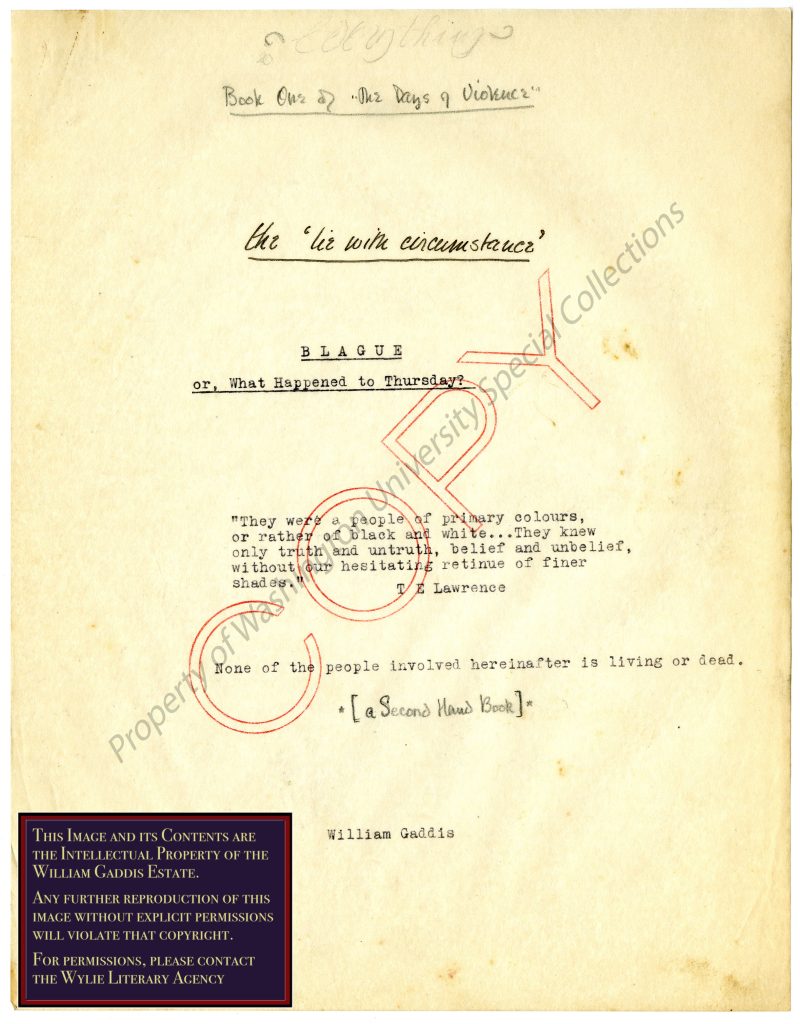

Title: Blague

Location in archive (Box.Folder): Fragments and notes throughout almost every The Recognitions folder. The major labelled folders that contain complete outlines and extended draft material specifically from Blague are in Box 20, folders 8 and 10.

Date: 1946-7: in an April 1947 letter to his mother Gaddis says that he is working on Blague, for which he had had the idea “about a year” before, his earliest notes having been stolen (Letters 69). He says he has done 5000 words (of a planned 50,000) that month, 10,000 a month later, with plans to send to a specific publisher. After this he talks with less commitment: it “will either be done or collapse” (Letters 78). Later he tells Katherine Anne Porter that “it took me five months to realize how pretentious it was” (Letters 103), indicating that he abandoned it by the end of summer 1947 and never completed it despite solicitation from an agent to do so.

Complete? No

Extent of preserved material: Five-page complete outline for shorter version, and 65 pages of continuous draft of first two chapters (second incomplete) in 20.8. In 20.10, a four-page outline (with more scenes described in less detail), draft forewords, over 100 typescript draft pages (longest continuous draft is 17 pages), most with manuscript revisions and additions, and over 50 pages of handwritten notes. In 82.27, title page and draft page. Fragments and draft pages throughout other folders.

Description & Analysis: The title Blague is French for a certain kind of frivolous and meaningless joke: Gaddis himself glosses it to his mother as “kidding […] But it is really no kidding” (Letters 69). In the story’s world, it names one of two chorus-figures: “Levi and Blague” drive around in a dual-control car, one dressed in black, one dressed in white, and give “lessons” and commentary to the story’s characters with a deliberately moral-existential flavour, talking of “moral responsibility,” “choice,” “decision,” and good and evil: the story’s explicit themes.

The fuller outline, specifying that “the action takes place in 24 hours, from the dusk of one day to that of the next,” gives us ten main scenes: Levi and Blague alone feature in a further prologue and epilogue. The story concerns a faltering love triangle: Charles is a bad-faith husband still in love with his old flame “Miss Horse,” a dancer (see entry on “Who is Miss Horse?” below), while ignoring his actual wife Madelaine. Madelaine “has always felt herself helpless” and drifts through life conscious of how inattentive Charles and her lover Ellery are to her, but doing nothing about it other than planning to write a novel in which she will vindicate her choices. Ellery, meanwhile, is merely selfish, “a person who feels no responsibility for anyone, anything” and has never given thought to good and evil. Losing his physical interest in Madelaine, he has no remaining care for her.

The first three planned scenes give us Charles and Madelaine’s perspectives either side of a party in which the misery and uncaring of this relationship become apparent to everyone in it. The fourth scene is a dream in which Madeline crucifies a figure she realizes is her son. Next, Charles takes her out to his family’s home in the countryside but the bad atmosphere there sends them each independently outside, whereupon he accidentally shoots her having thought she was an animal in the undergrowth. The chorus-pair in the dual-control car take her to the hospital, their existentialist “banter” establishing “that Madelaine (as is everyone) is wholly responsible for anything that has happened to her.” Ellery, meanwhile, seeks more violent excitement in his life and subsequently crashes his motorbike. The pair in the dual control car turn up, by a comic mishap twisting his neck and killing him in the attempt to save him: they flee the police.

At the hospital Charles sees Ellery’s body brought in, and also discovers that Madelaine can be saved at the expense of the baby she is carrying. Unsure whether the baby is his or Ellery’s, he seizes on this chance of a slate-clearing return to a simple two-person relationship. Having made that decision he then attempts to reconnect with Madelaine, but she, now awoken not only from sedation but to her true responsibility for her own life, turns him down and then “breaks into insanity.” Charles spills out into the street, where he is greeted by Levi and Blague in their black and white clothing, who invite him into their car for a lesson. He wants to know where to sit, they “encourage him to make the choice,” and finally he makes the decision to reach for the steering wheel, which, as they drive, is popped off and given to him, causing the car to lurch and bump his head.

He has a dream in which he sees people lined up into categories of good and evil, but unsure which is meant to be which he notes that one set is dressed in black, the other in white. Looking at his own clothes for guidance, he sees that he is “particoloured” in both. He thus wakes: “realising that good and evil must co-exist,” he gives the wheel back, but the car crashes. The epilogue sees Levi and Blague by the smoking car, bantering and walking off so that “the sound of laughter became the only real thing there was.”5

There is some kind of draft or serious note-taking for almost all of these scenes. The fully drafted chapter 1, titled “Where is Miss Horse?” bears little direct relation to the independent story of that title filed separately elsewhere (see entry below). The only sustained drafts beyond this are unstructured passages of party atmosphere and talk that grow out of the incomplete party-scene chapter 2, focusing in particular on the discussions between Charles and a party-goer called “Mr Kuvetli” (in the outline, “Mr Astrakhan,” a name seemingly salvaged from other story drafts – see entry below on “Mr Astrakan Says Goodnight”), an Egyptologist who discusses “the hidden prophecies I have come across in my work.” Shorter looser drafts exist of both Charles’s and Madelaine’s dreams, and of some of the “bantering” conversations the couple have with the men in black and white, which expand on the existentialist thematics of the story, as in Charles’s protests about control of the steering wheel: “Take the wheel” “you have chosen… You have made absolutes, and chosen between them” “Are there no absolutes?” “There was yourself” (7).

Blague seems to have been Gaddis’s first attempt to outline and write a novel-length project, after much apprentice work in short stories. The high proportion of the outline and drafts taken up with clunkily symbolic dreams and conversations that explicitly lay the themes out, rather than drafts of actual narrative events, reflects his struggles to make the long format work. That he turned to writing and rewriting apologetic forewords and many-epigraphed title-pages also indicates the difficulty of making the slender plot contain the various ideas Gaddis wanted his first novel to address. The comparative simplicity of the characterization and ideas—with everything finally reduced to impossibility and laughter—leaves the dreams doing all the imaginative work while the drafts tend toward shapeless capaciousness in the party scenes and fragmentation in everything else.

Blague thus seems to be a short story’s worth of imagination asked to bear a career’s worth of moral and existential interests, and there’s little indication that Gaddis was happy with much of what he wrote for it, hence the “Foreward” that contrasts it with good short stories and appeals to Gaddis’s own youth as excuse and as compensatory interest: hence too his retrospective explanation to Katherine Anne Porter that he had abandoned it for “pretentious”ness. There’s some mildly amusing characterization—“when she had loved her husband, the notion of anyone calling him Chuck offended her. Now she was offended at being married to anyone who could be called Chuck” (3)—and occasionally precise allegorical writing—“the car left the road and started through the trackless, empty air”—but not much that Gaddis could build a novel around. Elsewhere, in a note on Ducdame, he highlights “the hospital in Blague” as a valuable scene: something “histrionic, strictly theatrical” but that might be worth building on (“Why Ducdame Should…”). Most of the writing, though, is of the laborious over-explanatory kind that Gaddis, in that Ducdame note, identified as “my bad style”: within Ducdame drafts he would simply label whole pages “BAD.” The main interest in the Blague drafts is seeing Gaddis working in a more symbolical style than he would attempt again, the undigested influences of Nathanael West and French existentialism to the fore.

Relation to Gaddis’s Published Writings: As the sporadic filing of Blague material throughout the Recognitions drafts makes clear, there was a linear progression from Blague to Ducdame to the final novel. While Ducdame picks up Blague’s central relationship in various ways, the various irrealisms or surrealisms are dropped, along with the explicit existential thematizing. The long shapelessly-drafted party scenes are what survive: though they have little equivalent in Gaddis’s short fiction, such scenes become foundational to both Ducdame and The Recognitions.

Elements of Blague’s characters, meanwhile, gradually evolve into Ducdame figures who then become direct parts of The Recognitions: Ellery’s obnoxious self-exoticising on the basis of a brief trip to Mexico in the party scene drafts is an origin for Otto; Wyatt emerges from a combination of Charles and Mr Kuvetli; and Madelaine’s relationship situation becomes Esther’s, her passivity a characteristic of Ducdame’s Eva, who becomes Esme. Not until Carpenter’s Gothic, though, would Gaddis attempt another female focaliser.

One-off elements here, like the strange leap into insanity that follows from Madelaine’s assumption of her responsibilities, become more organizing elements in the final novel: half the cast of The Recognitions “break into insanity” by its later stages, and Blague helps reveal some of the intellectual underpinnings of that chaos: it stresses the impossibility of keeping hold of a workable worldview when you try both to take responsibility for yourself and to comprehend how much of what happens is down to cruel, ridiculous, blaguey chance. As Madelaine says pre-insanity, “suppose I had an accident?” “That, of course, would be your own fault… We [as driving instructors] cannot afford to assume such responsibilities” (61).

That The Recognitions grows from this initial attempt to write a short schematically organized existentialist love-triangle novel helps cast different light on the final novel: while the most commonly identified and analysed themes in The Recognitions have been its anti-modernity and concern with forgery and art, it turns out that these emerged initially as hooks around which to discuss more conventionally existential authenticity and responsibility.

Blague is thus also the paradigm case for a pattern notable throughout Gaddis’s writing, persisting at least as late as his immediate post-J R projects (see notes on The Blood in the Red White and Blue as discussed in Chetwynd, Nonprose Guide). His early drafts for projects like Blague, “Ernest and the Zeitgeist” (see entry below) and others foreground an explicitly cited array of French-existentialist sources and thematics, but then, in revision, make less and less of them until their originary significance becomes illegible.6 In the case of the shift from Blague to The Recognitions this is surely an improvement: the explicit chorus-voicing and allegorizing in Blague would be unwieldy whatever the philosophy they voiced.7

The aim to make the plot cover exactly 24 hours shows Gaddis attempting to write within one of the classical dramatic “unities” (time): he eventually works within another (place) in Carpenter’s Gothic.

Other Notes and Mentions Elsewhere? As his published letters of 1947 convey (Letters 70, 79), Gaddis intended during his early drafting to have Blague illustrated, he hoped by the German caricaturist George Grosz. Joseph Tabbi’s biography of Gaddis consequently discusses Blague as being from a time when “his vision of Western society was closer to the art of George Grosz than to the mythography of Graves and Toynbee, the thought streams of Emerson and Thoreau” (107).

Letters about Blague are highlighted for mention in John Tytell’s essay on “The Oppositional Writer,” which builds on a review Tytell wrote of the 2013 Letters edition.

Kevin Brazil stresses Blague’s “Armageddon” concerns (as elaborated in Gaddis’s letter to Katherine Anne Porter) when contextualizing The Recognitions in relation to the Cold War (81).

At various times Blague seems to have had a number of intended subtitles, alternate titles, frame narratives, and so on, often all at once. Gaddis drafted many title pages in which he tried to compile these in different combinations. See for example the especially proliferative Figure 1, which brings together three titles, a series location, an epigraph, two qualifications, an attribution, and the faint heading “~everything~”.

Gaddis also drafted a variety of forewords, most interestingly one in which meandering self-consciousness about the dreariness of forewords gives way to a direct recommendation to the reader to read something else:

Let me add only this. I have recently read a story called Mrs Razor, by a man named James Still. It is unpretentious, direct, honest, provocative, and direct. It deals with something beyond itself, which is implicit in itself: that is a small square of perfection. The author knew what he was doing.

I do not.

Neither do you.

“Mrs Razor” was published in the July 1945 edition of The Atlantic and concerns a six-year-old girl who tells her rural family she is married to an imaginary wastrel in the next village who has died and left her to raise her children alone. Her family humour her to varying degrees, but her belief outlasts their condescension. Written in simple sentences with vivid dialect and no authorial explanation of what is “implicit in itself,” it is indeed a direct contrast to Blague. Its concern with believing in self-made or contagious fictions beyond the point of usefulness makes it an intriguing early cipher for some of Gaddis’s later writing on the psychological function of fictions, most explicitly in Carpenter’s Gothic. But in form it resembles the realist regionalism to which some of Gaddis’s own short stories from his earlier time at Harvard seem to aspire: the Blague foreword highlights the extent to which this first longer project was a conscious venturing out beyond such templates into turf where Gaddis was less sure “what he was doing.”

Title(s): Ducdame / Some People Who Were Naked

Location in archive (Box.Folder): Dedicated folder in 20.6 (“The Recognitions: Ducdame 1947-8”). Draft and notes in 31.6 (“The Recognitions: Notes”). Material in 21.5 and 21.6 (“The Recognitions: “Notes and Fragments Toward other projects: ‘Sensation,’ ‘Waste,’ etc”). Other material interspersed throughout Recognitions folders.

Date: 1947-8 – Gaddis first mentions “plans for another novel” (after Blague) in a letter to his mother in December 1947 (Letters 82). The change in title from Some People… to Ducdame comes after March 1948 (see below). No rigid date at which work on this becomes work on The Recognitions but no mention under the two titles here from 1949 onward.

Complete? No, but extensive drafts.

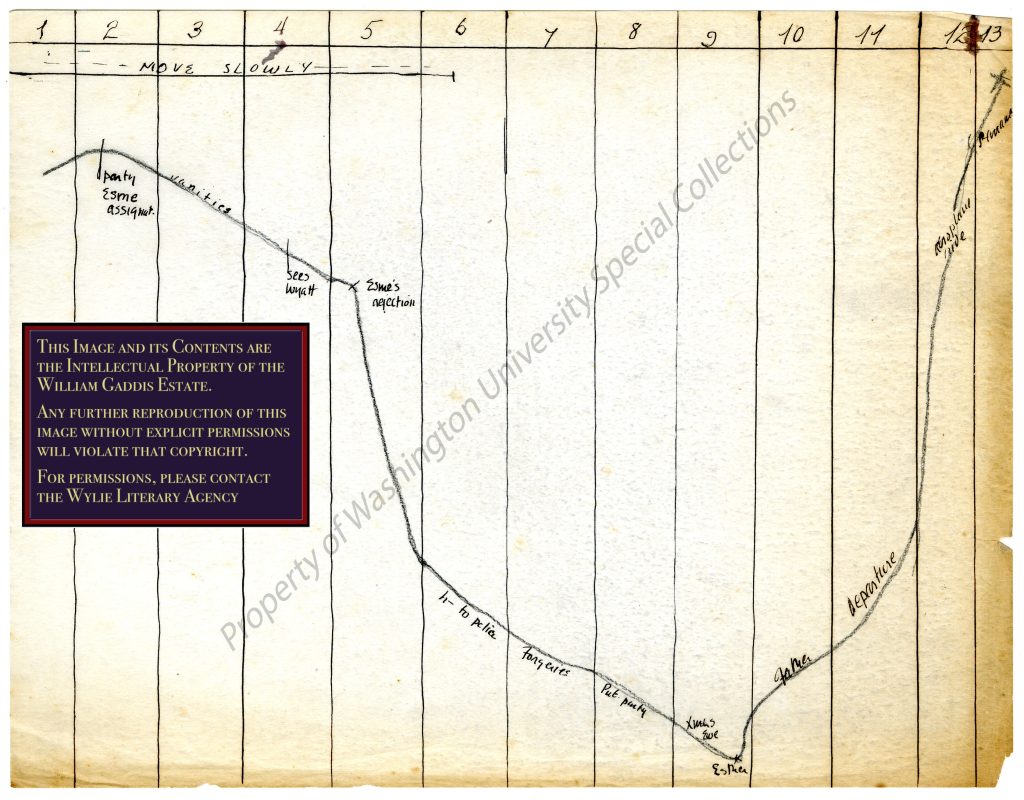

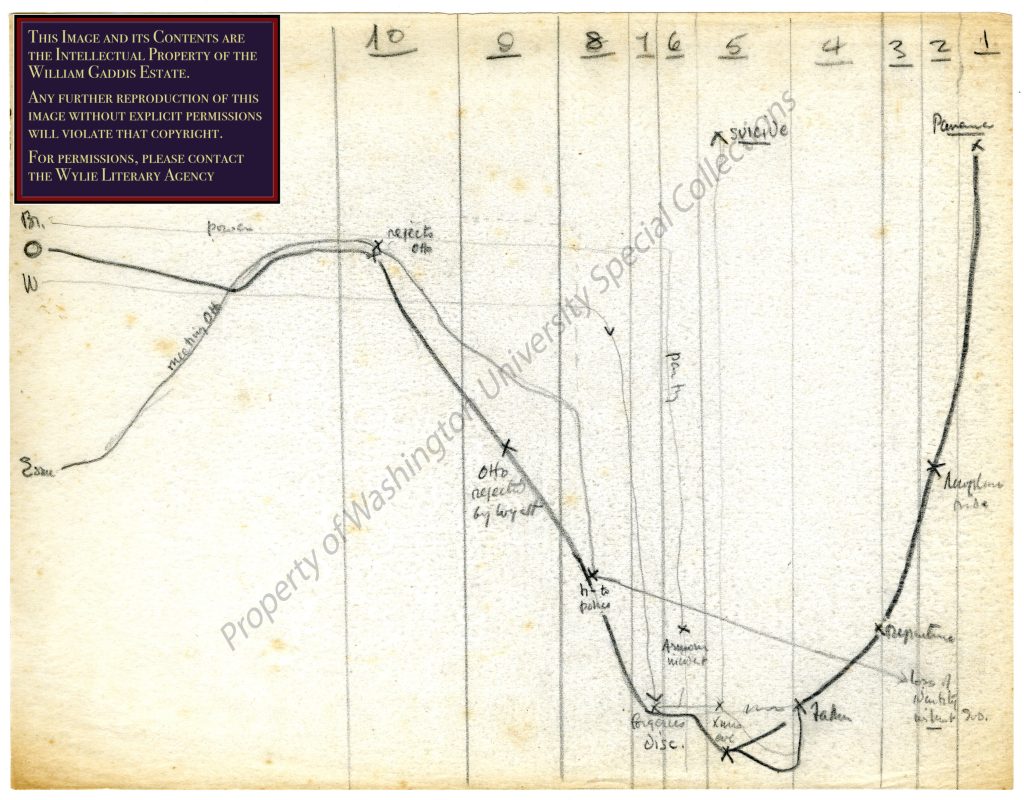

Extent of preserved material: Three extended section-drafts and roughly 100 pages of further notes and short drafts in 20.6. Hundreds of pages of notes, including “OUTLINE” and action-graphs (see Figures 2 and 3 below) in 31.6: all except one draft page of final novel’s opening seem to be from “Ducdame” era rather than Recognitions. Five pages of note-fragments filed separately in 21.5, four draft pages in 21.6. Many other fragments and draft pages throughout other folders.

Description & Analysis: Ducdame is essentially the Otto plot of The Recognitions, and at a certain point in its composition history Gaddis turns to writing that later novel out of Ducdame drafts, as his notes and drafts start to dwell more on Wyatt than prospectuses had intended and a whole new set of plots and themes emerge. Notes and fragments labelled “Ducdame” are found throughout the Recognitions folders of the archive, but extended drafts (discussed below) cluster together in a smaller number of folders. Some of the archivally preserved Ducdame material is directly revised into The Recognitions, but nothing in the final novel seems to survive in the exact form it was drafted for Ducdame. They should be seen as distinct projects rather than one simply being an early draft, even though the chronological and intentional dividing line between them is less clear than that between Ducdame and its immediate forerunner (and scavenged source) Blague.

Beyond the many pages of single-line fragment-notes, the archive preserves a number of character-lists, some visual sketches, and, as in the Blague archive, a number of draft sketch title-pages and frontispieces whose varying subheadings and epigraphs give a sense of Gaddis’s shifting priorities and intentions. Some of these he simply typed, others he diagrammed and then hand-inked in Gothic calligraphy. The likely earliest conception of Ducdame has the title (preserved on one such elaborate title-page) of Some People Who Were Naked (a reference to that version’s epigraph, from The Acts: “And the man in whom the evil spirit was leapt upon them and overcame them, and prevailed against them, so that they fled out of that house naked and wounded”). Gaddis mentions this title in a March 1948 letter to his mother (Letters 102). Ducdame is a nonsense-word from Shakespeare’s As You Like It, and title-page drafts supplement it with two potential subtitles: “The Lie Called Circumstance” or “The Vanity of Time” (the latter eventually the name of Otto’s play-in-progress in The Recognitions).8 Epigraphs veer from the portentous to the gnomic to the self-conscious, as in a quotation from an LP Smith dialogue about the appropriate contents of “the modern novel.” As with Blague, the amount of material on each of these paratexts keeps expanding and proliferating, until one version ends up with title (Ducdame); alternative title (“called: The Vanity of Time”); subheading (“Three Suicides Fully Explained”); categorization (“being: a Novel”); and promise (“with footnotes, an index, and an appendix: and: illustrated similes in true photographic reproduction”). Not to mention an epigraph. Even subsections of the planned novel get their own header-pages and epigraphs.9

The titled subdivisions reflect Gaddis’s schematic conception and careful scene-division. The biggest distinction between Otto’s story in The Recognitions and in Ducdame is that initially he was set to emerge triumphant: the final novel sees him bumbling through the world with occasional opportunities for self-comprehension comically avoided, but the Ducdame archive reveals how gradually this characterization came to be. First, Otto would simply have returned to New York from his time abroad to expose the vacuity of the New York partyworld he has seen beyond (this is likely the version for which the Some People Who Were Naked epigraph provides the key). Then, Otto would have returned pretentious and vain, but undergoing a series of experiences—romance with Esther, interaction and disillusionment with Wyatt, disappointment in meeting his estranged father, and return abroad—that led him to improvement and self-actualization. The opening half “Intentions” would trace his disappointments on returning, the second half “Dispositions” the development of his superior self.

Gaddis’s actual drafts, however, dwell and expand on the character of Wyatt beyond what any of the explicit planning material had intended. A circled, underlined note asks “Have I lost Otto?” Drafts that make Otto truly hopeless and ridiculous then start to shade into early iterations of The Recognitions. It’s unclear exactly when this happened, but Gaddis does not refer to Ducdame as a current project in his published letters after 1948.

The clearest models of the Otto-redeemed narrative that is best distinctly identified as Ducdame rather than Some People (Otto as heroic scourge) or early Recognitions (Otto as increasingly silly foil to increasingly central Wyatt) can be found in a 15-scene “Outline” and in two graphs for the rise and fall of dramatic action and character fortunes. The first parts of this are very continuous with the Otto plot of The Recognitions, with only slight variations. For example, “Eva” who becomes Esme has a “frighteningly apparent” “need for meaning” here, rather than frightening Otto by her self-sufficiency, and while her forgetting that she has slept with him happens in both novels, in Ducdame it is swiftly overcome as they resume a relationship that only later founders. The second half, though, would have seen reputable Wyatt exposed as a forger before committing suicide (thereby teaching Otto to care less about false accusations of plagiarism), Otto meeting his underwhelming real father (and actually recognising him in all his mundanity, by contrast to the comedy of errors around fatherhood in The Recognitions), freeing himself from Wyatt’s surrogate “sort of father figure” shadow, and finally having a positive revelation about himself while reading theology on an aeroplane to Panama, ending the novel wiser and more self-sufficient out there while his play made its own way back in New York.

The arc of the novel would thus have traced a fall and rise—from disappointments scrutinised by others to a fully regained sense of self—as Gaddis diagrammed it on a graph (archived in 31.6) whose unlabelled y-axis presumably measures Otto’s contentment from scene to scene (see Figure 2).

Other characters, meanwhile, would not have fared so well: the initial subtitle “Three suicides fully explained” plays out in a similar graph that plots the fates of four characters—Otto, Wyatt, Esme (Eva), and Br (Recktall Brown)—on the same axes (see Figure 3).

Brown would die as he does in the final novel (Ducdame thus incorporates the early stories on which this death was based, “Arma Virumque” and “In Dreams I Kiss Your Hand, Madam”: see entry below), Wyatt would commit suicide after the exposure of his forgeries, and Esme would lose “identity without God.” Only Otto, despairing at these deaths on Christmas day, would chart his way back upward, thanks to his meeting with his father which, revealing them to have nothing in common, would establish “Otto is alone. He begins to understand that.” That understanding leads him to care less about the calumny against his play, to leave Esther and her “appeals […] to his vanity,” and to become serious by reading theology on a plane. He would then return “to the sun, to burn out rottenness, to be alone, to do heavy work.” A final scene would show him back abroad, “all vanity apparent in ch. 1 gone,” with an ear infection barring off the outside world and his self-sufficient inwardness complete. A note page in 31.6 suggests that “each chapter open with quote from Faust. // Brown—satirical(ly condemned) Mephistopheles. / Wyatt—a fateful Faust / Otto—a regenerate Wagner.” With the exception of a sketched version of the final scenes in Panama, though, the Otto-redeeming plot exists mainly in notes rather than in writing, stranding Otto before he can become the mature artist who Gaddis had planned.

The most continuous preserved Ducdame drafts are of three sections, all in folder 20.6. A typed draft labelled “Ducdame 1: Intentions” focuses on Otto before his return to New York: this is likely very early as it moves through various attitudes to pre-return Otto, from reverence to ridicule. The largest set—a continuous 35-page handwritten ink manuscript headed “ducdame II”—is extended shapeless party dialogue, filed after large amounts of single-page notes and drafts of party detail. The third, and closest to what ends up in The Recognitions, is a more linearly narrative 18-page handwritten ink manuscript headed “Ducdame III,” which follows Otto on the day after his first night with Eva, before he finds out she has forgotten it.

The most illuminating supplement to these is that brief sketch version of Otto matured abroad (also the focus of the couple of pages in 21.6). This unlabelled set of draft pages comes with the ink note “No commenting in this chapter,” which highlights the over-explicit tell-not-showing way that its pages currently handle thematic implications, and their resort to representing Otto’s thoughts by mental quotation of the “he thought to himself” kind. Gaddis was apparently dissatisfied with this, planning to redraft in a style more like the final Recognitions. Rather than do that, though, he actually moved on to writing that very different novel, in which Otto achieves none of Ducdame’s intended flowering. Otto’s reading-prompted religious ponderings here—“if I go on thinking this way, will I be forced to come to terms with God?” or the note that he “must see lamb of God in Cathedral”—do link this planned ending to the religious concerns of The Recognitions (there developed through Wyatt and his family, rather than Otto). Beyond this, Ducdame otherwise lacks the theological themes and references that saturate the final novel. Otto himself is described here in terms of coherence “his linen hung calmly, clean and without elegance, upon the quiet movement of his body,” by contrast to the “Ducdame 1” drafts in which his over-dressed self-consciousness and preening vanity are emphasised. Otto was, early in the novel, to be solicited by a local prostitute to whom he would say “I understand everything but your words, Senorita” while in the draft ending his ear infection renders him deaf and self-contemplating so that, greeted by a priest, he would repeat (with greater implication) “I understand everything but your words.” There the planned novel would end.

One undrafted plan for the ending would have contained a further revelation: a note clarifies that “His name is Otto Mims – Otto Mims. Not revealed until last part of book – time of arrest.” Where the name Otto Pivner later came from is unclear, but “Mims” seems to suggest mimesis, and link to Otto’s constant Ducdame characterization as absorbed in mirrors: the name’s revelation would coincide with his outgrowing that predilection.

The archivally preserved drafts, then, are more sporadic than Gaddis’s notes, but do give enough of a sense of what a completed Ducdame would have looked like to see how its focus on Otto would have made it a very different, much simpler, novel.

The folders also contain material clarifying Gaddis’s approach to his compositional process, and, in 31.6, a multi-page set of reasons “Why Ducdame Should Be a Play” that both indicates his thoughts about the novel form and illuminates his subsequent work in more dramatic media (see the dramatic works discussed in Chetwynd, Nonprose Guide). The process-note shows how fully Gaddis worked on itemising the elements of his novel before writing it:

I: List

-

- People – and relative importance

- Information to be given about people

- Conversation & exposition

- Lines

- Of sequential intentions

II go through all notes, both books

III Outline

This indicates that Gaddis saw his novels of the time emerging from character first: perhaps not surprising given that Otto is overtly based on him and critics have been able to identify many of the characters in the New York section of The Recognitions, which grows out of Ducdame, with specific people he knew at the time. His character-first working method might also, however, explain the disproportion between the proliferating amount of Ducdame-era notes and the lesser amount of revised narrative draftwork Gaddis actually achieved: with the exception of a few passages about Otto, most of the extended writing beyond notes is shapeless “conversation & exposition” in which party scenes give information about characters. “Why Ducdame Should be a Play” shows that Gaddis thought about these struggles to write actual plot-developing novelistic work as struggles with the novel form per se. Theatre, he suspected, might better fit his schematic intentions “Because of the architectural quality of a good play – and I have been trying to write fiction in an architectural frame, and having a bad time of it.” Another note identifies that “I have seen the whole of both novels as tableaux. As sequential and consequential scenes,” which is borne out in the shape of his outlines for both Ducdame and Blague, but also in the “bad time of it” that he seems to have had in turning either project from planned scenes into working fiction. The growing interest his drafts show in Wyatt and Brown, rather than in Otto, suggests that he finally resolved this not by turning to drama, but by changing the focus of his story.

These and other notes also give us some sense of Gaddis’s attitude to his own writing. In a published letter to his friend Charles Socarides, Gaddis had lamented that while he liked the idea and story he was working on, “I watch myself ruin it” through “bad writing” (Letters 97). The archive preserves him making comparable observations to himself. One page gets the note “BAD, must be light,” (p7 of a handwritten draft in 20.6), while “No commenting in this chapter” on the very didactic final-chapter draft indicates dissatisfaction with his tendency to editorialize and substitute thematic notes for developing narrative. “Why Ducdame Must be a Play” shares this straightforward self-judgment, lamenting “temptations to my bad style which has grown worse of late.” That “bad style” is most clearly glossed in the letter as “trying to be clever –this perhaps because I am afraid to be sincere.” The combination of strenuous attempts to be “clever” with a failure to be “light” results in lots of passages of clunking over-explained irony (and imbalanced counter-weights of pathos) that read like bad imitation of Nathanael West, an influence Gaddis acknowledges in a letter to Katherine Anne Porter around this era. The failure to manage West’s tightrope balancing of simple diction, jittery bleakness, and queasily deadpan hilarity leads Gaddis to identify his bad style with an affect as well as a prose: “the fetid air that hangs over me – the mean bitterness, the temptation to get even &c,” hoping that drama, in its natural removal of editorializing narrative voice, would free him from this tendency and “temptation.” The root of the problem, as he identifies it, is that “I trust an actor more than I do a reader,” explaining his heavy-handedness in much of the Ducdame draft work. Gaddis’s regular meta-evaluative comments on the quality, promise, and failings of this work make the Ducdame archive of particular interest, since they are less common and explicit in the archives of his subsequent novels.

Relation to Gaddis’s Published Writings: Ducdame is obviously a direct forerunner for The Recognitions, generating one important thread of the final novel’s plot. It grows out from the social universe of Blague’s draft party scenes. Gaddis decided to send a version of himself into that world as Otto to “prevail[] against them, so that they fled […] naked,” then became interested in Otto’s own ridiculousness and what it might take to redeem it into seriousness, then “lost Otto” such that Wyatt became an increasingly central figure, at which point Ducdame as full Otto-novel was put aside, and Otto integrated into the new project. The Recognitions satirises authorial over-identification with protagonists, as Otto processes his real experiences through thinking what his own play’s heroic self-insert “Gordon” would make of them.10 This self-reflexive element is missing in Ducdame, in which “Gordon” is just the name of a minor party-goer.

Many figures who become important in The Recognitions are born as minor figures in Ducdame: the names Stanley and Agnes Deigh, for example, are given to minor party attendees: the former a poet translating TS Eliot’s French poems into English, the latter (whose name is pencilled in as a replacement for “Mrs Hillary”) a writer in professional competition with her husband and in social competition with Otto, having recently returned from “Porto Rico” as he has from Costa Rica. Very few of these same-named Ducdame figures are identical to their selves in the final novel: the least-changed survivor being Frankie (whose name becomes Chaby), Eva’s heroin-addicted pseudo-paramour. While most of The Recognitions’s New York figures have some origin in the party scenes of Ducdame, there is no obvious proto-Anselm, no proto-Hannah, no gang of homosexuals, and, despite the presence of Recktall Brown and Fuller, no Basil Valentine. The basic mechanisms of the first half of Ducdame’s Otto plot, from his being crushed by Eva’s failure to remember their night together, to his reporting Frankie to the police in retaliation, to the plagiarism controversy over his play, survive more directly than any exact characterization of minor characters.

The major figures differ in more precise and illuminating ways from their eventual forms in The Recognitions. The initial plan to have Otto himself become a wise and mature figure, close to fulfilling Wyatt’s Recognitions resolution “to live deliberately,” is one such distinction, and abandoning this plan meant that development had to come elsewhere in the novel at the expense of Otto’s comical stagnation. Esther is more genuinely besotted by Otto, making her decision between him and Wyatt into more of a genuine romantic triangle: her opinion of Otto (and his eventual ability to disregard it) is thus more central to his own developing self-conception. Eva/Esme is more straightforward in this version: a mere “nihilist” whose “frighteningly apparent” “need for meaning” shows her path as a flawed one, unlike the Recognitions version whose inner world never becomes comprehensible to the men who project their desires onto her. Wyatt—whose evolution does more to distinguish Ducdame from Recognitions than any other character’s—starts in early drafts as a more serious update from Blague’s quack prophetologist Mr Kuvetli. He is characterized above all in relation to alcohol, which “he confessed, had a similar effect on him to that of the fumes from the pit of Delphos upon the priestesses.” His air of mystery attaches to a controlled state of in-between drink—“In his sobriety there waited a kind of querulous intoxication; and when he had been drinking, a far-seeing sort of clear sobriety”—and his final confession about being a forger, which precipitates his collapse and Otto’s moving beyond his father-surrogate relation to him, comes when he “finally” gets uncontrollably drunk.11 Alcohol becomes less defining of Wyatt’s character in The Recognitions than in Ducdame.

Thematically, meanwhile, Ducdame has differing, and far narrower, emphases but on its own turf a broadly shared palette with The Recognitions. The controversy over Otto’s play being seen as plagiarised is a much larger part of Ducdame, where it is meant to reflect the play’s genuine connection to the wellspring of tradition. The plagiarism accusation reflects worse artists’ envy of Otto, while by The Recognitions the plot serves to stress Otto’s derivative inauthenticity, by contrast to Wyatt’s authentic forgery. Wyatt’s forgeries here, meanwhile, only serve to help Otto see the significance of his own authenticity, rather than opening up the aesthetic and historical-cultural concerns of the final novel. The father-relationships in Ducdame would have been limited to Otto’s perspective and much more easily resolved, while religion would matter only as the missing end-stop for Eva’s “Nihilis[m]” and as a ratification for Otto’s seriousness in the final scenes. On the other hand, some emphases in Ducdame, like the stress on Otto’s changing relation to mirrors, or the saturating register of “certain”ty and doubt (doubt in Ducdame sometimes reflects thoughtless reflexive scepticism, sometimes embodies serious engagement with the world beyond certainty) drop out by the time of The Recognitions. Other elements, like the plan to have Otto gain interiority by losing his hearing, play a less obvious role in The Recognitions but illuminate Gaddis’s career-long paratextually-attested concerns, like the value of being “inner-directed.”

The “Why Ducdame Should Be A Play” document, similarly, casts less immediate light on The Recognitions—which ended up written in the same basic prose-forms as Ducdame, only less didactically handled—than it does on Gaddis’s later works which have less linguistic space for the psychological interiority prose fiction makes available and that a play must find ways to do without. As those later novels do more with the interaction of dialogue and external description, they follow through on Gaddis’s “Play”-insight that “words should be and are spoken and done.” This document is also a key for understanding his actual, generally unsuccessful, work in dramatic media (See Chetwynd, Nonprose Guide).

Other small details and visible corrections simply raise spectres of very different potential Recognitions: Wyatt, for example, was initially planned to have spent time in Haiti, before a series of these references are crossed out and replaced with references to Spain, to little effect in Ducdame but with major influence on The Recognitions.

Other Notes and Mentions Elsewhere? Gaddis refers to Ducdame in published letters to his mother in late 1947 and early 1948 (Letters 82, 85, 86 , 89): the first time to say that he is planning it, the second and third to describe his working conditions (unable to type continuously because of disturbing neighbours, and so writing by hand and making lots of notes), the fourth to describe the “incredible slowness” of his progress on it, working from midnights to 4am. He discusses further struggles with it months later in a letter to Charles Socarides: though it “fits so insanely well with facts of life,” “I watch myself ruin it” through “bad writing,” an example of which he extracts for proof (Letters 97).

The title comes from Shakespeare’s As You Like It (act 2 scene 5), where it is repeated in a song, and the fool Jacques glosses it (fantastically) as a “Greek invocation, to call fools into a circle.” Like Blague, then, the title may be a joke on the readers it brings into its own communicative circle,12 or it might gloss the initial “Some People…” conception of Otto bringing knowledge of his crowd’s foolishness to them.

Potential subtitle “The Lie Called Circumstance” is the name of the symbolic-of-life-itself play in “The Rehearsal” (see entry below).

The extended handwritten meditation on “Why Ducdame Should be a Play” is briefly mentioned in Chetwynd, “Stylistic Origins,” in relation to J R’s formal qualities.

Titles: Sensation, & Rose in Print

Location in archive (Box.Folder): Sensation material in 21.5 and 21.6 (The Recognitions: “Notes and Fragments Toward Other Projects: ‘Sensation,’ ‘Waste,’ etc”), notes in 82:27 (Short Fiction: “Unfinished”), two note pages in 80.2 (Agapē Agape: “Unsorted”), notes with Sensation characters moving into J R set-up in 40.2 (“J R or the Boy Inside Partial manuscript”). “Rose in Print” brief notes in 21.5 and 21.6, material otherwise in 80.2.

Date: Sensation work 1955 or early 1956, title earlier, plot possibly conceived earlier; “Rose in Print” later, possibly as late as 1961 (Sensation precedes J R, while some notes on “Rose in Print” indicate connections to J R figures who don’t exist in Sensation, and to Once At Antietam, written 1959-61).

Genre: Sensation a projected novel, “Rose in Print” to be a subsection of Sensation, then to be a text-within-the-text of Sensation, then possibly to become part of early J R. Its final resting place is as a briefly mentioned (Gibbs-authored) text-within-text of J R.

Complete? No

Extent of preserved material: Sensation, despite prospectively being the bigger project, survives in less material: a two-page prospectus plus character list in 21.5 plus separate notes to self on a relationship, headed “October,” which correspond to mentions of October in the “Rose” material. A brief note toward “PART III,” a page of notes on weather and setting, and notes on character of Dick in 21.6. Two pages of planning notes in 80.2, and two more in 82.27. More from this era, not explicitly labelled as Sensation, may exist elsewhere in the archive, especially the J R files, which are largely unsorted by date or section.

“Rose in Print” material comprises a variety of note pages and three draft sections of between three and six pages. A note page headed “ELISE: MY WISTFUL SYMPATHY, MY TENDER LIKING” is filed with “Rose in Print,” and mentions figures and plot points (“pheasant” “October”) from the Sensation notes and mentioned in the “Rose in Print” drafts.

Description & Analysis: “Rose in Print” seems to have grown out of—at one point to have been a planned subsection of—Gaddis’s first projected successor to The Recognitions, which was to have been called Sensation: “Rose” is the second name on a list of characters headed “Sensation” in 21.5. The bulk of the preserved draft writing on either project seems to be on “Rose in Print.”13

It’s unclear who Gaddis wrote his short prospectus of Sensation for, but it must have had an intended audience unfamiliar with The Recognitions since more than half is taken up with describing how the theme of “The Self Who Could Do More” works in that novel; this will be an interesting document for anyone interested in Gaddis’s own interpretation of his works. Sensation is offered as a contrasting approach to that same “central theme of THE RECOGNITIONS in an entirely different context, style, and treatment” (1). Projected to be less than 1/5 the length of Gaddis’s debut, Sensation would be about a family devoted to music across many generations, but only whose adopted son in the third generation actually has any genius, causing “the disintegration of a small family into whose midst a figure of the totally competent ‘Self who can do more’ is introduced” (1). In “treatment,” meanwhile, where The Recognitions “was a complex often abstract pictorialization of values and evaluations; SENSATION is quite straightforwardly a novel of human frailty” (1).

Notes indicate that the two most resentful brothers would be called “Jan and Earn,” and this is key to identifying a document in which the Sensation to J R transition seems to happen most clearly. In 40.2, a three-page series of typed notes pages indicate that a novel should start in a funeral scene, at which “Edward” raised as the son of successful musician James Bast (the object of Jan and Earn’s resentment) would find that “he is not fathers [sic] but uncles [sic] son” and have to decide whether he should give up on the musical destiny he thought he had inherited. The funeral scene would highlight the distinction between “inheritance of estate and talent.” This, then, is much of the J R plot grown out of Sensation and just awaiting the invention of JR himself to consolidate the shift in projects. All the surrounding material is about JR and J R. It’s likely that more early Sensation material is hidden away in the profuse and unsorted J R archive folders.

Despite the promise of a simpler, more “human” approach, the other document of continuous Sensation notes (in 82.27) hints that some version of the project might have gone in a more abstract direction than the musical-talent plot that became J R. These notes point to something even more surreal than anything in The Recognitions, as a dead patriarch conscious of being buried hears his children discussing what to do with his legacy: “Thud wakes him: vague sense who’s in the attic? after my books?” But it turns out they are not after anything of him as a person: “The brothers arguing about property &c. But neither of them wants his watch nor his books, ie the books he’s written, freethinking &c.” The old man is already being lost to the past, and, in a fairly direct “pictorialization of values,” this is because “He is Reason, 19sie dogmatism &c.” The sister of these brothers would be the one who attached some value to him rather than his “property,” asking the brothers to dig him back up.

The two loose pages of Sensation notes filed along with the “Rose in Print” material, meanwhile, are mainly to do with theme rather than plot: aphoristic notes like “we love people for the good that we do them and we hate them for the harm” and “I can endure my own despair, but not another’s hope” indicate the kinds of family dynamics Gaddis had in mind, with the few more plot-specific notes—eg, “he has been corrupted by his work […] why she loves the ‘success’ ie not because he is -, ie – not in the terms which the failure, the bete noir – interprets to himself in his self-pity”—relating to these overall issues of jealousy and mismatches in mutual valuation.

This “she” is likely “Rose,” the extra-familial figure whose judgment mediates between “success” and “failure.” Gaddis’s notes around the project seem to suggest that this was based on his experience with a specific woman, as they shift into the first person to contrast what he is doing in his work with the experience of an “I.” Most directly relating Gaddis and Rose to the Sensation plot, a note points to “my work: how it abruptly became her approval which was important, no matter mine, nor friends’, nor critics &c&c: only, what would She think of this word, this conceit, &c&c&c.” This all contributes to a fairly hostile characterization of the Rose figure: one page of notes opens with “Point Rose is a witch” and, presumably from the protagonist’s perspective “that she has castrated him, married Norman (power).” The fore-running here of the J R plot in which Stella, Bast’s cousin and Gibbs’s former lover, marries the businessman Norman Angel makes clear that Rose is a Stella prototype, though some notes suggest Rose and Stella could have co-existed in early plans for J R (see below). Notes also link her to DH Lawrence’s “cocksure” women: “she will behave independent, but, if she follows through (as she must […]) be laid low & need rescue.” These notes turn into drafts where Rose’s self-sufficiency is stressed—“Rose, young but no girl, beautiful out of context and aware of that, stayed out, entirely or until her late presence merely confirmed one she’d established of her own”—along with the harm this does to the men who think they can handle her: “she’d go on appearing to take each at his own evaluation, letting that build without her interference out of all proportion till when she side-stepped, and it fell, it came from such a height that there were a good many pieces.”

This theme of the damage done by mismatches in how we evaluate ourselves and how others evaluate us survives from the Sensation prospectus, but it’s notable how little plot there is to the various “Rose” drafts: they are either straight description or characters’ thoughts about or around Rose as they do menial things. The notes mention images and events to associate with Rose, and her relation to characters from the Sensation cast and the J R cast, but nothing directly states what the narrative of “Rose in Print” would be. Some of the draft pages have page numbers as high as 105, starting in the 90s, suggesting that Gaddis may have written much more than is currently locatable. In what’s preserved, though, the plot element that comes up most often is a pheasant hunt—“his country house / field in Oct / pheasant, stone wall, ec”—notable for its eventual use in the play Once at Antietam (where a pheasant is found cowering into the stone wall as if to avoid the horror of all violence). Antietam is subsequently reproduced as Oscar’s magnum opus in A Frolic of His Own, and Oscar takes great pride in—and greatest exception to the film-adaptation’s distortion of—the beauty and sensitivity of his pheasant scene, “that scene I wrote in all its classic simplicity turned into trash” (412).14 But even Gaddis seemed to struggle for a sense of how this would contribute to a Rose narrative: one note wonders “her pheasant hunt – but what significance has it?” Struggling for a narrative that could sustain this character outside her function in the superceded Sensation, Gaddis’s notes resort to overall atmosphere: “decline and death are the climate of this thing.”

Eventually, what seem to be the final few pages of consistent “Rose” draft solve this problem by turning “Rose in Print” into a text within a text, able to give us the character and contribute to “climate” without having to be a complete story. A character “McColl,” thinking at a friend’s apartment of his own Rose-like romantic encounters, “seeking refuge, found a magazine already opened to a story, Rose in Print, by Hyman Kleinowitz [pencil note] Grynszpan [/pencil note]” (draft page II 98). Hyman Grynszpan is a pseudonym used by Gibbs in J R. The Rose story then takes over McColl’s narrative until a side-note two pages later—after the passage from “Rose in Print” ends and we return to McColl—suggests that we “pick up next page later, he finds it under sofa ec- throughout.” In the final version of J R, Gibbs reads from his own story “How Rose is Read,” similar in style but without much overlap with this draft (see J R 584). Only one element is conspicuously re-used. In the “Rose” drafts, McColl’s own paramour (within his level of fictive ontology) is “no book heroine as they wanted.” In J R, this is part of Gibbs’s description of his heroine: Rose. A pencil note on the McColl passage says “How Rose is Read,” giving us the source of J R’s Rose-title, and foregrounding Rose’s relation to printing, reading, textuality in general.15 This emphasis survives into J R. As Steven Moore notes in discussing the Gibbs-reading passage, Gibbs throughout the novel has a tendency to “think of the women he meets in literary terms,” so that the way he writes about Rose belies his own distanced way of relating to people (Moore, “William Gaddis” 116). If initial “Rose” drafts frame her as a proto-Stella and eventually even Stella’s relation, in final J R she’s an explicitly fictive figure symptomizing Gibbs’s dysfunctional relation to women (including to Stella…). Had “Rose in Print” stayed an independent project to J R, it’s unclear whether Rose would have been “human” or “textual” in the story’s own ontological level.

“Rose in Print,” then, seems to have evolved from a character central to Sensation, into one connecting the Gibbs and Bast plots (like Stella does) in the earliest versions of J R, into a fictional heroine in whatever larger thing McColl was part of,16 into a passing one-off marker of Gibbs’s pathologies in J R. It’s unclear at what point Rose-as-actual-character dropped out of J R, but all the drafts of her story here are written in conventional prose that matches the novel’s earliest preserved material.17 At least one very early J R note gives her a key schematic relation to the novel’s two core characters: “Bast the romantic seeking ‘reality’ & Rose is unreal & JR is unreal.” But while the notes about her relation to Gibbs (who unlike Bast has no roots in Sensation) indicate that she kept a foothold as J R took over as Gaddis’s main project, she seems not to have survived far into the novel’s drafting.

Relation to Gaddis’s Published Writings: Both texts earn a passing mention in a completed novel. Gibbs’s creation and reading of “Rose” in J R is mentioned above. In The Recognitions, amid the narration of Reverend Gwyon’s death and the transport of his ashes, someone is reading a novel called SENSATION.18

In the August 1956 letter-to-self that copyrights the basic idea for J R, Gaddis says that “the book just now is provisionally entitled both Sensation and J R” (Letters 269). He also notes that “I started to develop this idea into a short novel no later than March 1956.” As Elliot Yates’s contribution to the present special journal issue documents, February and March 1956 were when Gaddis did his first corporate writing with Textron and picked up an interest in the narrative possibilities of “diversified” corporate expansion. Since the Sensation prospectus draft makes no mention of young JR or the business world (even though its Bast material later merges with J R), this suggests that it dates to a time before the Textron work shifted Gaddis’s interest from the performing artist’s family to the business world. That the 1956 letter maintains Sensation as a possible title should not indicate that Gaddis still thought of J R as the same family-disintegration Recognitions-counterpart project that the Sensation prospectus describes. Similarly, that he had the title in mind early enough to include in The Recognitions doesn’t mean that he had already developed the prospectus’s prospective plot by then. The earliest the prospectus could date is to the immediate aftermath of The Recognitions’s publication, since it mentions the novel’s reviews; other planned notes might date slightly earlier, as some are filed along with correspondence and other material dated in later 1954. The “Rose in Print” material, by contrast, may well have been parallel to work on J R as late as the early 1960s, since it is only at that point that we find datable J R material really distinct from the “Rose” plans and drafts.

In the few Sensation notes filed with the “Rose” material, we find two important links between Sensation, “Rose in Print,” and the next two book projects for which Gaddis would actually get contracts: J R and Agapē Agape. The note on “Sensation Openings” mentions “Rose as it stands (& into Bast) […] Children at seashore & Body washed in […]Dream of Rose (& intimacy),” which suggests that some version of “Rose” has already been written and confirms that the name “Bast” was part of the Sensation plan. Meanwhile, a pencil note on the “Sensation a novel” page of notes says simply “Agape [sic] Agape,” which—if we date the Sensation project to before Gaddis sent himself the prospectus for the basic J R plot in 1956—may be the earliest use of this phrase/title in Gaddis’s archive.19

The obvious connections between Sensation and J R are supplemented by “Rose” material in which the Rose character was meant to interact with characters who exist in J R but not in the (Bast?) family-centric model of Sensation. A possibly later pencil note at the bottom of one page of “Rose” notes says “REVIEW this [out/cut] Rose situation, cf Stella; [illegible] & pheasants; Rose gbbs dghtr’ Gibbs & Aimée […] a final of apotheosis to it all in sx seq f VIII.” While this is mainly cryptic, it establishes that “Rose in Print” survived into the J R vision of characters like Gibbs and Amy Joubert, and that in casting about for a place to locate Rose in the newer project, Gaddis considered making her Gibbs’s daughter, leaving her to wreak her harms on other men, even as Stella continued to do this to Gibbs himself. By the time the novel is completed, those of Rose’s characteristics like her “witch”y charisma that do survive do so as qualities of Stella, such that it makes most sense to read Gibbs’s writing about “Rose” as sublimations of his attitude to Stella.

“Rose”’s pheasant scene, as mentioned above, is part of the unpublished Once at Antietam which was then repurposed in A Frolic of His Own and framed as a part that Oscar, the play’s author in that novel, is especially proud of. A scrap of paper in the files notes a connection to J R characters “Gibbs/Eigen cont. to pheasant sc. Which also appears in Antietam.” So it seems Gaddis was planning to use the scene across projects, and also dates this scrap to after he had Once at Antietam underway, so 1959 at earliest.

A pencil note on the final “Rose” draft (in which “Rose in Print” has become a text-within-the-text) mentions “Freya goddess of love” and some notes about the male norse gods killing each other, and links this to “B’s libretto” (II 100), presumably some indication of what music Bast in this early version would be composing. In J R, Gibbs compares Stella to Freya (282).

The figure of the “self who could do more” who serves as the explicit bridge between The Recognitions and Sensation in the prospectus is a crucial one throughout all of Gaddis’s novels, most often in the characters with most autobiographical relevance. It then becomes most explicit in Agapē Agape where Gaddis quotes the same line of Michaelangelo that he does in the Sensation prospectus (and which he had already quoted in The Recognitions).

Meanwhile, to round out the relevance of the fragments of “Rose in Print” to every subsequent Gaddis novel, a pencil note on the text-within-a-story draft suggests changing the character’s name from McColl to “McCandles” (II 99). “McCandless” then, 25 years later, becomes the name for a central figure in Carpenter’s Gothic.

Other Notes and Mentions Elsewhere? The archives on these proto-J R projects compile a lot of evidence of what Gaddis read and wanted to cite in the mid-1950s, both in literature and in music. For example, in addition to the explicit sources and citations mentioned above, one single note-page mentions Hawkes’ The Cannibal and Svevo’s As a Man Grows Older as cases for the note-claim “Life is a Dream,” then “Dvorak’s 4th, Bthoven’s 6th” as musical conversation topics for a “dumpy catbird.” The archives here, however fragmentary, will thus be of interest to anyone interested in Gaddis’s influences, sources, and intertexts.

Title(s): Theatre / Fictions / The Late Mr Slyke / Concentrate on the Real Story

Location in archive (Box.Folder): 82:10 (Short Fiction: “Notes, Possible Projects Aborted”)

Genre: Projected at different times as novel or as play, about cinema and film-making.

Date: 1979-1981.

Complete? No

Extent of preserved material: Typed “synopsis” in two versions (incomplete 1-page called “THEATRE” and complete but annotated 2 pages headed “TITLES: THEATRE”). Ten pages of typed notes and fourteen pages of handwritten notes, some continued on reverses.

Description & Analysis: This disparate set of notes, with no extended drafts, concerns a potential play or novel that would orbit the making of a film, extending into something between a murder mystery, a meditation on collaborative creativity, and an exploration of the relationship between fiction and truth.

While none of the materials are clearly dated, it seems likely that this set of plans took shape after Gaddis’s second round of (failed) attempts to find a producer for either a J R film adaptation or his western screenplay, which was circulated under the name Dirty Tricks in 1977-8 (see entry in Chetwynd, Nonprose Guide). Gaddis explains the planned project directly in a 1979 letter to his daughter, as “some bad news rich people making a movie […] an inept murder plot or 2” (Letters 425). By July 1980 a letter to Tom LeClair mentions “a book already but barely started” (Letters 435), which seems to be before there is any clear archival indication that what we now know as Carpenter’s Gothic was underway, but suggests more progress than is indicated by the lack of archived drafts for the “movie… murder” project. A page of notes containing the fragment “Again the entire corpus of US law as $oriented: the Ron Gillela case as PARASISITM [sic] utterly legitimated” dates at least some work on this project after the Gillela events of 1981. A late 1979 latter to John Napper refers to a novel rooted in Shakespeare’s Sonnet 73 “That time of year…” which does become a major source for Carpenter’s Gothic, so it’s unclear whether Gaddis was working on these two projects in parallel, or whether his “movie… murder” story also had the autumnal ruins of Sonnet 73 hovering over it before Carpenter’s Gothic came into being. While we can’t be certain about dates, this project seems to have derived from Gaddis’s own experiences with the periphery of the film industry while shopping Dirty Tricks, and to have been sidelined as he either invented or prioritised Carpenter’s Gothic beginning in the early 1980s. Elements of this “movie… murder” work then make their way into Carpenter’s Gothic and A Frolic of His Own (see below).

The archive traces at least four differing versions of the project, with differing prospective titles, and even different planned genres (play, or novel). The basic idea of a murder-mystery related to the film industry evolves, losing the murder focus, to become more about the process of film making. At some point, Gaddis decided that the machinations—whether these be of murder-motivating financial contracts, or film-production interest-wrangling—would be about the adaptation of a book into a film, and that the book in question would be one of his own unpublished drama projects: either the play Once at Antietam or the western screenplay Dirty Tricks (see entries in Chetwynd, Nonprose Guide). The most definite articulation of the overall theme of the eventual project comes in a “synopsis” headed “(TITLES: THEATRE; TITLE OF THE MOVIE (NOT ANT),”20 which sets out a project “about an attempt to create a coherent fiction—one with the logic of a beginning, middle and end— from the chaos of the conflicting interests, temperaments, and viewpoints of the characters of the book, all of which are dominated and distorted by money.”

The most coherent sequence we have been able to postulate for these four versions is as follows.

The (likely) initial model, in notes mentioning the title “Concentrate on the Real Story,” simply sees the film industry as a viable setting for a murder story concerning an unscrupulous producer taking advantage of the opacity of the various contracts on which the creation of a film depends. This corresponds to Gaddis’s summary in the 1979 letter to his daughter. Notes here treat the project as a play, which begins “K has taken girl to country house (lent him by writer?).” The “girl” in question would be called Liz, and the plot would partly revolve around abuse of her younger sister by this unilaterally exploitative producer figure.

The project then seems to evolve to concern the producer’s suicide, with the plot revolving around untangling his legal and financial legacy: the title “The Late Mr Slyke” (the name of the producer in this set of notes) corresponds to this era, also, for the first time, raising the issue of how reality and the works of fiction we treat as industries interact: “Point: is the woman’s covering for the man’s suicide in Real Life or the Fiction?” Somewhere within this era the interest of film as a collaborative artform and industry seems to have come to the fore, and we see plans and notes focusing less on Slyke’s viciousness and the murder plot, more on the contractual and artistic complexity of adapting works from single-author media into multi-maker film. Gaddis seems to have vacillated between whether his Faust Western or Once at Antietam should provide the source text in this model, but here is the germ of the way A Frolic of His Own eventually repurposes this old work.

This batch of notes seems closest to what finally became Frolic, as under the name “FICTIONS (NOVEL),” we hear of a character somewhat like Oscar: “The writer, at first elated at his book’s ‘second chance’ as a film, goes from fighting to reserve its integrity in the script to becoming as venal as anyone.” The writer’s concerns would have corresponded to many of Gaddis’s own archivally-preserved concerns about potential adaptations of J R: “Now they are going to ‘novelize him the movie, different title &c & no mention of him puts his novel out of business entirely where he’d hoped for big paperback sale.” The action here would have happened mainly on the film set rather than in the world around it, with conflicts and role-blurring among all the contributors to a film (for example the writer interceding to yell “cut” and leading the director to quit), the script being mysteriously improved from day to day with no one knowing who is making the changes, and so on. Gaddis’s interest in the relationship between fiction-making, the individual writer’s imagination, and the complex collaborations of a film project leads him to envision various unspecified formal blurrings of his own narrative levels. The differing fictions of the plots of source-text and film-adaptation, the fiction-building lives of the people around the film, and the ongoing fiction-reliant project of the film plot would increasingly saturate each other. Structural notes along these lines suggest “That the fiction must gradually take over […] the end plays upon/resolves the beginning ie the end being the last rewrite” while in “the early part the real informs the fiction; as it progresses, the reverse sets in.” Gaddis had a final vision of the significance of this plot: “POINT: It must be the Fiction which prevails (but for being more true).” What that “prevailing” would look like, the archived documents do not show.

The longer fuller synopsis titled simply “THEATRE” would not involve suicide or complexities about collaborative fiction-making, but rather end up as a divorce story as the wife came to understand how Schnick had been defrauding her: “In the end, aware that if she puts up the rest of the money and the project succeeds, he will leave her, she refuses, destroys him finally but keeps the wreckage for her own: what she is saying is, unless his success goes with my success I don’t want it.” It may be an attempt to simplify away from the growing metafictional concerns.

Yet these come back in the incomplete “THEATRE: TITLE OF THE MOVIE” synopsis, where all the varying elements and emphases—from the highly metafictive to the psychology of marriage and manipulation—seem to be most resolved and balanced. It begins by establishing the character of “Schnick” (no longer “Slyke”) as “a man of numerous schemes gone wrong” who has “no experience whatsoever as a producer” but has the option on a book and needs to make it into a film. The novel would then concern the production of this film, itself not shot in sequence, leading to the difficulty of “creat[ing] a coherent fiction,” which would then spill out into the form of the novel itself, film-making being “the constant dislocating reference point for the real story, dislocating since the film constantly threatens to supersede the reality—as in the end it does.” This document thus contains all the elements that the various notes to the project touch on, and seems like the final synthesis before Gaddis moved on. A note at the top of the page impels—presumably to Gaddis himself— “Remember the purpose of this synopsis”—but its exact audience and purpose remain unclear: there is no indication that it was ever circulated to agents, producers, or anyone else.