Adrianne Wortzel's response

Praise for the body art of Camille Utterback, and commentary on controls.

Praise for the body art of Camille Utterback, and commentary on controls.

Early on in the feature film Superman, reporter and professional victim Lois Lane falls from a helicopter dangling from the roof of a New York skyscraper. Plummeting to her certain death, she is rescued in mid-air by Superman (aka: a man made of steel [and, for all we know, in some instances, of bits and bytes]), in his first appearance both in Metropolis and in the film. Such is his innate tenderness and his fine-tuning as a deus ex machina that he alters his ascending velocity to her descending velocity in order to spare her any damage from their impact. As he scoops her up in his arms, he reassuringly exclaims: “I’ve got you!” She instantly responds, with the awed and inquiring mind of a journalist always seeking empirical truth: “But who’s got YOU?”

This exclamation of awe mirrors the amazement (and in some cases, horror) with which we contemplate our technological achievements during pit stops as we plummet through progressive stages of technology, reinventing ourselves and extending ourselves beyond the limitations of our bodies, not to mention our dogmas and credos. We are never satisfied, and this makes for great copy. By all means, we say, “Let’s move on out into unknown territories, let’s mix our metaphors, and let’s face it - if we can make it through the rough and tumble ride down the birth canal and emerge intact and cognizant, then we can do just about anything.”

Born grounded as a species we nevertheless insist on flying. Faced with the physical step-by-step traversing of huge distances in order to communicate, we demand, and get, immediate connectivity. Frustrated with conjecture as to what the earth really looks like, we invent machines that empirically remove us far enough away from the earth in order that we may turn around and look at it. Thwarted by disease and injury, we act as avid detectives and risk-takers to “beat” them. Eager to have the last word in territorial disputes, we invent the ultimate semiotic machinations of obliteration. While we may freely let our inventions loose in the world, we also doggedly attempt to keep control over them because we are also fearful of their control over us. It is this dichotomy of control and losing control that many artists deal with in working with new technologies.

Camille Utterback’s Text Rain is one of my favorite works in the world, in that it acts out the manipulation of text through physical will. In doing so, it not only gives us pleasure but also actualizes the pluralistic significance of words as message, meaning, metaphor, symbol and object. In her writing here, she covers well the story of artists’ working with external manipulation by extending ourselves physically. I would like to add some comments on the externalization of these controls by way of attaching computing mechanisms to the body itself and, alternatively, internalizing them.

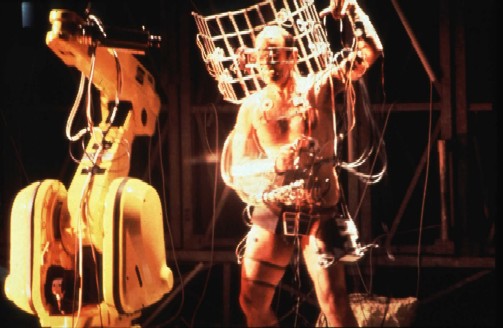

Stelarc’s performative works are driven by a philosophy that engages the obsolesence of the human body and the championing of cyborg development.

18.response.1. Stelarc’s Exoskeleton. Cyborg Frictions, Dampfzentrale, Bern, 24 November to 1 December, 1999. (Photo Dominik Landwehr, permission Stelarc)

For artists working with extensions of biological functions, in order to express metaphors, they have to work literally, attaching themselves to or ingesting devices. Stelarc comments:

It is time to question whether a bipedal, breathing body with binocular vision and a 1400cc brain is an adequate biological form. It cannot cope with the quantity, complexity and quality of information it has accumulated; it is intimidated by the precision, speed and power of technology and it is biologically ill-equipped to cope with its new extraterrestrial environment.

Stelarc’s work transcends the model of “prosthetic” when it turns in on itself and interiorizes the computing process and its products into the body. In Ping Body/Proto-Parasite, this kind of reversal occurs:

…the cyborged body enters a symbiotic/parasitic relationship with information. Images gathered from the Internet are mapped onto the body and, driven by a muscle stimulation system, the body becomes a reactive node in an extended virtual nervous system [which] extends the body’s optical and operational parameters beyond its cyborg augmentation of third arm, muscle stimulators and computerised audio visual elements.

…The body, consuming and consumed by the information stream, becomes enmeshed within an extended symbolic and cyborg system mapped and moved by its search prosthetics… [via] sensors, electrodes and transducers on its legs, arms and head that triggered sampled body signals and sounds and that also made the body a video switcher and mixer [Stelarc].

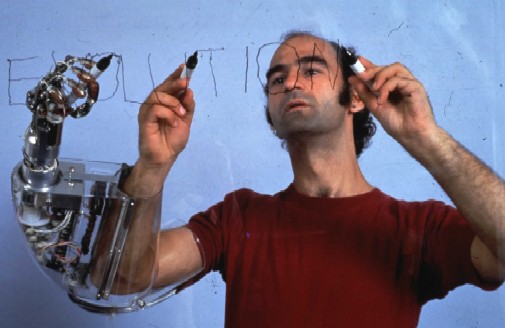

18.response.2. Stelarc’s Handswriting — writing one word simultaneously with three hands. Maki Gallery, Tokyo, 22 May, 1982. (Photo Keisuke Oki, permission Stelarc)

Here the elements move to the state of appendages rather than extensions.

There are works that deal with even more complete interiorization of computing elements INGESTED into the body via emerging forms of biotechnology and there are many artists working to utilize them in their art, which often becomes politicized as a result. That is to say, these aren’t simply experiments in biotechnology, they are statements about our relationship with machines, computing, and the world.

As early as 1997, in his work Time Capsule, Eduardo Kac implanted a microchip in his ankle. The microchip isa transponder… Scanning the implant generates a low energy radio signal (125 KHz) that energizes the microchip to transmit its unique and inalterable numerical code, which is shown on the scanner’s 16-character Liquid Crystal Display (LCD). Immediately after this data is obtained I register myself via the Web in a remote database located in the United States. This is the first instance of a human being added to the database, since this registry was originally designed for identification and recovery of lost animals. I register myself both as animal and owner under my own name. After implantation a small layer of connective tissue forms around the microchip, preventing migration.

He goes on to say:

The body is traditionally seen as the sacred repository of human-only memories, acquired as the result of genetic inheritance or personal experiences. Memory chips are found inside computers and robots and not inside the human body yet. In Time Capsule, the presence of the chip (with its recorded retrievable data) inside the body forces us to consider the co-presence of lived memories and artificial memories within us. External memories become implants in the body, anticipating future instances in which events of this sort might become common practice and inquiring about the legitimacy and ethical implications of such procedures in the digital culture. Live transmissions on television and on the Web bring the issue closer to our living rooms. Scanning of the implant remotely via the Web reveals how the connective tissue of the global digital network renders obsolete the skin as a protective boundary demarcating the limits of the body.

Subsequent works by Kac deal with the exchange between human and robot of both information and material substance. In A-positive, a biobotic work by Eduardo Kac and Ed Bennett, blood was transferred from a human to a robot, dextrose from the robot to the human - man and machine exchanging nutrients in a symbiotic relationship. Alba, the green fluorescent bunny, was created with a synthetic mutation of an existing gene found in a fluorescent jellyfish. Kac describes this work as “a new form of art based on the use of genetic engineering to transfer natural or synthetic genes to an organism, to create unique human beings.”

The journey depicted in films like Fantastic Voyage (1966), where a medical team invades a stroke victim’s body in a terrifically shrunken vessel in order to administer to the patient (who happens to be a pivotal player in the midst of a Cold War crisis) may be a nanotechnology metaphor and only a potential holodeck experience now, but somehow, and very soon, a version of it will be more actualized, and artists will be there creating evocative works.

In this response, mostly for mischief, I have opted for a paradigm of distinctions consisting of three modes of describing works that, as Utterback says, “explore the interface between physical bodies and various representational systems…” These modes are 1) extending the body, 2) attaching things to it, and 3) ingesting or physically morphing the body.

In regard to this, questions to consider are: are these categories a fruitful way of analyzing works that interface between body and machine? Will this be true in the future? Do these distinctions cover the entire range between what we expect from imitative avatars and actualized cyborgs? Should these three modes be considered in an order of progression, i.e. representing progress as they move, let’s say, from extension, to attachment, to incorporation, and aligning with developing technologies? Is it important that artists align themselves with ever-new technologies or is there merit in engaging in retroactive technologies, and if so, what is the meaning in that merit?

In an interview on The Early Video Project, the artist Les Levine has said this wonderful thing in regard to video art:

…it was a new medium in the early sixties… And then it became a new medium again in ‘72, and then it became a new medium again in ‘81, and it became a new medium again in ‘92 [Gigliotti].

Video, of course, is becoming a new media again at the time of this writing, with new compression and streaming technologies via the Internet. How then should an artist working in developing technologies, whether as context or content or both of those as the same thing, think about the moving target of technology, if at all, particularly as a new representational art form engaging humans as interface?

I suspect Utterback, in future work, may be one of those who helps us re-imagine the old chestnuts of bodily engagement and network media. I would like to know her plans or how and if this is on her mind.

References

The Stelarc web site at http://www.stelarc.va.com.au/

Fantastic Voyage, 1966 - Studio/distributor: Fox

Cast

* Stephen Boyd

* Raquel Welch

* Edmond O’Brien

Director

* Richard Fleischer

The Early Video Project - http://davidsonsfiles.org/LesLevineInterviewPart1.html. Les Levine Interview by Davidson Gigliotti. Recorded: December 9, 1999.

Cite this essay

Wortzel, Adrianne. "Adrianne Wortzel's response" electronic book review, 22 March 2004, https://electronicbookreview.com/publications/adrianne-wortzels-response/