Dark Souls as Networked Hyperlinked Videogame

Austin Anderson applies a videogame formalism methodology to Dark Souls and argues that the game's various ludic-textual structures challenge player expectations, encouraging them to engage with the game's multiplayer systems and explore fan-made paratextual materials. By defining the player's movement between these structures as an act of hyperlinking which creates a networked community, Anderson identifies these as key characteristics of what he calls the 'networked hyperlinked videogame'.

Introduction

On 20 January 2018, the YouTube video essayist Nakey Jakey, the persona of Jacob Christensen, released a video titled “Dark Souls Saved Me”, where he talks about his first exposure and play experience with FromSoftware’s 2011 action role-playing videogame Dark Souls. Unlike his typical video essay style which features a script, visually diverse composition, and frequent jokes interspersed with videogame footage, “Dark Souls Saved Me” is entirely static and unscripted, with Nakey Jakey saying, “I haven’t really written anything down, [and] I’m just going straight from the heart” (0:13-0:16). In the video, Nakey Jakey lays in bed on his lefthand side facing the camera, yet his eyes look just below the camera’s lens [Figure 1]. Outside of a single clip for a “drink break” (6:17), the video never changes composition nor cuts to gameplay footage. Instead, viewers watch the same static shot for the entire 9:31 runtime. It feels intimate, something multiple comments on the video highlight such as: “This video felt like having a deep nostalgia convo with a friend at 2 a.m.”

The video’s content is likewise deeply personal as he describes a time when he “was pretty poor” and “very depressed” and how this was when he began playing Dark Souls (0:52-1:03). Nakey Jakey discusses becoming enchanted by the game while “reading up on the lore” by watching the popular YouTuber VaatiVidya (5:18), a lore-hunter who summarizes Dark Souls’ different NPCs and storylines in a highly narrative form. Without engaging with game studies, Nakey Jakey proves himself an excellent player-critic of Dark Souls as he identifies the game as “obscenely obtuse for someone to get into it” (1:15-1:19)—which several game studies scholars have rightly called a defining element of Dark Souls (Marco Caracciolo; DA Hall 2024; Cameron Kunzelman; Daniel Vella). Similarly, Nakey Jakey describes how his introduction to Dark Souls was entirely dependent on a player community, describing how his brother encouraged him to play Dark Souls and then served as his “strategy guide and made it so that [he] could play through the game essentially on easy mode” (2:17-2:21). Game studies has likewise long recognized that community curation is embedded in the Dark Souls player experience (Sky LaRell Anderson; Caracciolo; Mateusz Felczak; Olle Sköld). Nakey Jakey proceeds to describe Dark Souls in decidedly therapeutic terms: discussing how the game gave him a “sense of control” (7:37), “felt like a religious experience” (8:06), and made him think, “if something like that can exist in this world […], this is a world that I want to live in” (8:09-8:12). The video concludes with him looking at the camera for the first time while saying, “Thank you, Dark Souls” (9:20).

In the saturated market of YouTube videogame essays, it is notable that an unscripted love letter to a then seven-year-old—and now fourteen-year-old—videogame has resonated with many; at the time of writing, it has been viewed nearly two million times, received 106K upvotes, and 4.5K comments. Yet, what is perhaps most intriguing about “Dark Souls Saved Me” is how the video is part of a larger genre of video essays about the therapeutic capacity of Dark Souls. There are dozens of popular video essays on YouTube where players describe how Dark Souls helped them overcome a personal hardship [Figure 2].

While each individual video is apocryphal, the collection of these video essays reveals a shared experience among players who describe Dark Souls in therapeutic terms. This experience is not contained to YouTube video essays alone; Marco Caracciolo’s research shows that this therapeutic sentiment is often expressed by players in the Dark Souls online community (81-86). I find this phenomenon especially noteworthy because it mirrors my first experience with playing Dark Souls in 2020 at the height of the COVID-19 lockdown.

While I am neither interested in nor qualified to explore the actual therapeutic potential of videogames (T. Atilla Ceranoglu; GE Franco), I do want to probe why Dark Souls seems to engender this therapeutic response in many, though certainly not all, players. At first glance, Dark Souls would not appear to lend itself to this type of player response; the Hidetaka Miyazaki-helmed action-RPG videogame features a notoriously difficult combat system, an evasive storytelling style, and a dark fantasy setting organized around cycles of death and rebirth. While Dark Souls is quite influential as one of the major entries in the Soulsborne series—which includes Demon’s Souls (2009), the Dark Souls trilogy (2011, 2014, 2016), Bloodborne (2015), and Elden Ring (2022)—and the inspiration for the Souls-like genre, many other influential videogames have not produced a similar player response.1 Why does this videogame elicit a therapeutic response in so many players?

To answer this question, I employ Alex Mitchell and Jasper van Vught’s methodology of videogame formalism, which is “an approach to studying videogames as texts of systems with assumptions about how videogames work aesthetically, the types of responses players can have to them, and how they relate to the world around them” (22). Videogame formalism uses the player-critic’s gameplay experience as “the departure point of the poetic analysis” of the videogame under-consideration (Mitchell and van Vught 32). For this reason, this essay began by establishing that many player-critics have had a therapeutic response to Dark Souls.2

Once the player response is identified, videogame formalism “asks what combination of (or struggle between) devices is at work in evoking that experience” (Mitchell and van Vught 64). Caracciolo points out that “Many players ground [their] claim about [Dark Souls’] therapeutic effect in an existential interpretation that considers both DS mechanics and the elusive narratives that traverse the game world” (86). In other words, Dark Souls’ various formal structures seemingly inform the therapeutic response that many players have had with the game.

According to videogame formalism, “the aesthetic experience of a work” is produced by “a process of defamiliarization and refamiliarization” (Mitchell and van Vught 81). Defamiliarization is “the process of making the familiar strange to enable us to see things anew”, while “refamiliarization is the process of working to find connections between the unfamiliar foregrounded elements and the larger context, so as to make sense out of the process of defamiliarization and find a way for this to be meaningful to the player beyond the game” (Mitchell and van Vught 81).3 This process of defamiliarization and refamiliarization encourages players “to see the familiar in an unfamiliar way, not for its own sake, but as a way to break out of the tedium of everyday life and see what we see everyday in a new, fresh light” (Alex Mitchell 10). This process explains why many players have had a therapeutic experience with Dark Souls that has, in turn, helped players confront a real-life issue—be that depression, loneliness, or other personal hardships.

Dark Souls presents its gameplay information—such as its mechanics and narrative—in a defamiliarized manner; in doing so, the game defamiliarizes our understanding of videogame play and encourages refamiliarization through what DA Hall calls a “meaning-making” through “community itself” where the community “engages in an unending and collaborative negotiation of meaning within and around the worlds of the game series” (2024, 14). If we return to the Nakey Jakey video, Dark Souls’ structures are “obtuse” and defamiliarize his understanding of videogame play, which inspired him to seek out both his personal community (his brother) and various paratextual Dark Souls communities (VaatiVidya) to then become refamiliarized and discover how Dark Souls’ various systems work. This process of defamiliarization and refamiliarization inspired him to reflect on his own life and think, “if something like that can exist in this world […], this is a world that I want to live in” (8:09-8:12). The methodology of videogame formalism allows us to uncover how Nakey Jakey and other players’ therapeutic response was curated by the game’s various structures. However, what I am keenly interested in is how this process is achieved by the player’s movement between Dark Souls’ various formal systems and external fan-made paratextual materials.4

This article introduces the concept of the networked hyperlinked videogame through a case study of Dark Souls. The networked hyperlinked videogame is a videogame whose ludic-textual structures (e.g., mechanical difficulty, gameplay systems, narrative presentation, etc.) encourage player-led digital exploration (via paratextual materials like wikis, lore videos, and online walk-throughs) while simultaneously curating a networked community both within and beyond the game world. By applying the videogame formalism methodology to Dark Souls, I argue that the game’s various ludic-textual structures defamiliarize videogame play and thus encourage players to seek clarification in external digital paratextual materials such as wikis, walkthroughs, and lore videos.

Drawing on hypertext theory, I view these actions as a practice of hyperlinking. Through this practice, the game cultivates an ecosystem of network exploration that spans both the game’s in-game asynchronous multiplayer elements (e.g., message system and bloodstains), in-game synchronous multiplayer elements (e.g., summoning and invasions), and external out-of-game materials (e.g., the Fextralife Wiki and Vatividya lore videos). Through these systems, Dark Souls encourages community engagement to comprehend Dark Souls and work for refamiliarization. The networked hyperlinked videogame is therefore a type of videogame—exemplified by Dark Souls but not necessarily exclusive to it—that encourages community creation through the specific response it produces from players.

This article proceeds in five parts. First, I situate the networked hyperlinked within the theoretical traditions of videogame formalism and hypertext theory. Second, I briefly review the major critical literature around Dark Souls, which I group into two major trends: ideological reification and political praxis. I argue that these divergent responses can be explained through videogame formalism because the methodology recognizes that each player’s lived experience influences how they respond to any videogame under consideration. Third, I offer an overview of Dark Souls’ different ludic-textual structures—such as its narrative presentation, mechanical difficulty, and multiplayer elements—to show how they defamiliarize videogame play, which, in turn, encourages a practice of hyperlinking where players are drawn into a networked discourse community organized around Dark Souls. Fourth, I offer a close reading of the Ornstein and Smough boss fight to show how the game functions as a networked hyperlinked videogame. Finally, I conclude by briefly exploring some areas of potential further application of the networked hyperlinked videogame.

Theoretical Framework

This article draws on videogame formalism and hypertext theory. The emphasis on defamiliarization in videogame formalism provides a productive way to understand the aesthetic experiences generated by the different structures of a videogame, while hypertext theory offers a means to analyze how players navigate and respond to these defamiliarized experiences. In this section, I will offer a brief overview of the videogame formalism tradition before turning to a discussion of hypertext theory, particularly the poetics of the hyperlink.

Mitchell and van Vught’s videogame formalism focuses “on the ways in which the game as an object, when put in motion through the process of play, creates an aesthetic experience against the backdrop of both the context of production and the context of consumption” (36). Their methodology draws from Russian Formalism, Neoformalist Film Theory, and previous formalist approaches in game studies. Two ideas are particularly important for this article: the focus on a videogame’s devices and the concept of defamiliarization.

The videogame formalist Holger Pötzsch explains that Russian formalism’s “most important contribution to game studies […] is the focus on formal devices as empirically observable features of games that systematically restrict and predispose player performances and perceptions, this way enabling particular meaning potentials to emerge.” Both Russian Formalism and Neoformalism argue that all the parts of a text have a reason for being there. This is called motivation, which is “a cue by the work that prompts us to decide what could justify the inclusion of the device” (Kristin Thompson 16). As a methodology, videogame formalism asks player-critics to consider their own play experience and pay special attention to how certain devices are “foregrounded over others” (Mitchell and van Vught 114). This focus on the various structures of a videogame is foundational to videogame formalism.

The other key term is defamiliarization. While its usage in videogame formalism was outlined in the introduction, it is necessary to expand on its origins in Russian Formalism. Viktor Shklovsky famously argued, “The technique of art is to make objects ‘unfamiliar’” (16), and this creates an estranging effect that “challeng[es] reader and spectator [… and thus enables] us to truly see, rather than merely recognize the world around us” (Pötzsch). Videogame formalism asks player-critics to focus on the defamiliarizing structures within a videogame. The interpretation of these elements allows the player-critic to see reality with fresh eyes via refamiliarization, which allows “the unfamiliar” to become “meaningful beyond the work” (Mitchell and van Vught 62).

By applying a videogame formalist reading to Dark Souls, I aim to show how Dark Souls’ various ludic-textual structures defamiliarize videogame play. This effect encourages players to adopt a hyperlinking practice where they seek out external paratextual material and the game’s internal multiplayer systems to make sense of the game. In doing so, a networked community emerges among players who have a shared investment in Dark Souls. In defining this practice as hyperlinking, I draw from broader theoretical discussions in hypertext theory, particularly the poetics of the hyperlink.

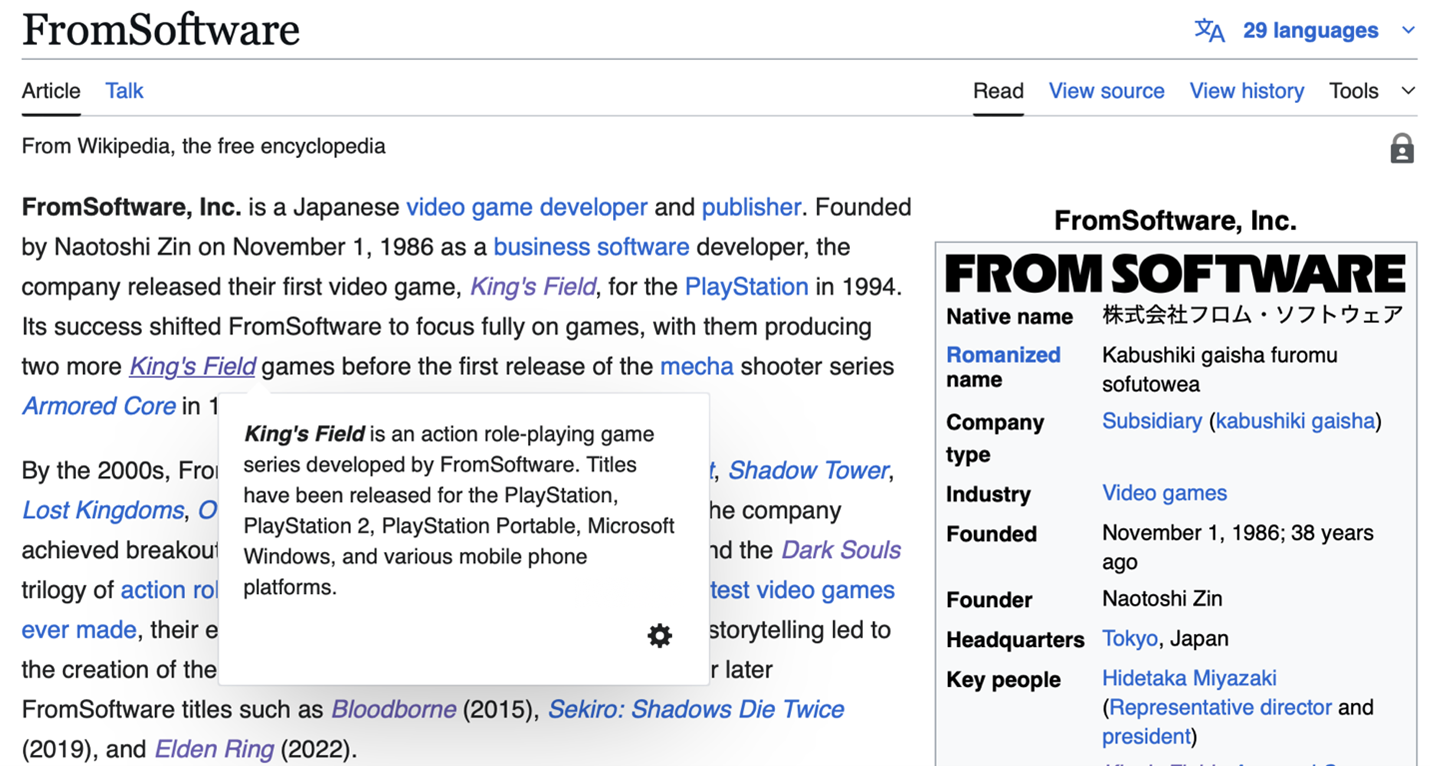

Hypertext theory has long theorized the hyperlink (J.D. Bolter; Astrid Ensslin; George Landow), and the discipline provides the necessary entry point for understanding the practical and poetic work of the hyperlink. A hyperlink is “a technological capability that enables, in principle, one specific Website to connect seamlessly with another” (Han Woo Park and Mike Thelwall). At a definitional level, a hyperlink connects discrete modes of information, e.g., linking from the “FromSoftware” Wikipedia article to the “King’s Field (video game)” Wikipedia article [Figure 3]. Yet, beyond their navigational function, hyperlinks inform how users experience digital space, especially the Internet, and Lada A. Adamic points out that “the hyperlink frequently reveals very real underlying communities.” Thus, while an “univocal, unambiguous interpretation of the link does not exist” (Juliette De Maeyer 747), hyperlinks provide a structuring force that enables user navigation of the World Wide Web.

Given the role of hyperlink in structuring digital environments, scholars such as Zizi Papacharissi, Jurgita Matačinskaitė, and Terje Rasmussen have shown how hyperlinking—from both a curatorial standpoint (e.g. an author deciding which hyperlinks to include on a fan wiki page) and a user standpoint (e.g. the practice of the user clicking different hyperlinks to follow the various nodes that are presented with on a given webpage)—plays a key role in digital community formation. Hyperlinks also influence “the overall size and shape of the public sphere” (Joseph Turow 4) by facilitating the transmission of online discourse and enabling users to traverse digital space. This hyperlinking practice also creates micro-communities where users bond over shared interests. In the case of Dark Souls, the hyperlinking practice occurs both inwardly (as players engage with the game’s internal networks of signs and multiplayer elements) and outwardly (as players move between the game itself and a vast array of external paratextual materials such as fan-created gameplay guides or lore videos). Moreover, the game’s design actively encourages this behavior through the defamiliarization effect of its various ludic-textual structures. As such, Dark Souls functions as a hyperlink hub that directs players outward and draws them into the Soulsborne micro-community.

Hyperlinking also produces an aesthetic and Jeff Parker’s “poetics of the link” highlights how hyperlink texts generate temporal disruptions as users navigate from one node to another.5 David Ciccoricco similarly describes hyperlinking as producing a feeling of “repeated disorientation and reorientation” (80) as the user is pulled away from the primary text and brought to an unfamiliar secondary environment. Scott Rettberg expands on this effect and describes how “the reader’s activation of the link ‘calls’ another text, media object, or programmed aspect of the work that in some way changes the text delivered by the computer and/or network to the reader’s screen” (2002). Hyperlinking in Dark Souls similarly disrupts the player’s play session by providing them with new contextual information or gameplay techniques that they may bring to bear on the text itself. In this way, the networked hyperlinked videogame is informed by previous theorization of the poetics of the hyperlink.

In invoking videogame formalism on the one end and hyperlink theory on the other, I aim to show that the formal ludic-textual structures within Dark Souls encourage a specific hyperlinking player response where players engage with Dark Souls’ multiplayer elements while also searching the game’s many fan-made paratextual materials. This player response curates the networked community that I view at the heart of the Dark Souls and Soulsborne experience, a community often mentioned in therapeutic responses of the game (Writing on Games; Ember; Nakey Jakey; Caracciolo). Importantly, videogame formalism does not foreclose the possibility of alternative player responses, which can explain the conflicting readings of Dark Souls in game studies.

Reading Dark Souls in Game Studies: Competing Perspectives

Videogame formalism begins its analysis from “the player’s experience of a videogame,” which is “the combination of cognitive and emotional/affective responses to external stimuli and the player’s own […] specific, lived context” (Mitchell and van Vught 80).6 The approach recognizes that every play session is informed by “the researcher’s own cultural and social predispositions” (Torill Mortensen and Kristine Jorgensen 11). Approaching Dark Souls through videogame formalism can help explain the dichotomous readings it has received from game studies.

In the nearly fifteen years since its release, game studies has been working to define the critical and aesthetic work that Dark Souls and the larger Soulsborne series offer. This critical conversation has only intensified following the success of Elden Ring (2022), which expanded critical interest in Soulsbornes; for instance, the 2025 issues of Games and Culture and Game Studies, two of the field’s flagship journals, together feature four different articles devoted to Soulsbornes. Some of these studies offer focused attention to individual elements within a Soulsborne game such as Enrico Gandolfi’s analysis of Twitch streams of Dark Souls III or Mark Hines’ close reading of Godrick the Grafted in Elden Ring through the lens of democratic political theory. However, many other scholars have offered broad interpretations of the Soulsborne genre and its cultural impact. As a general rule, these works can be split into two interpretative camps: ideological reification and political praxis.

Scholars in the ideological reification camp argue that Soulsbornes align with or actively reinforce the value systems of late-stage capitalism. For instance, Cameron Kunzelman contends that “the Soulsborne genre carries within it an expectation of a certain type of labor under a certain regime where an individual must rise to a meritocratic baseline in order to be valorized” (179). Daniel Dooghan offers a parallel critique, arguing Dark Souls simulates an economic fantasy of late-stage capitalism while being “monstrously necropolitical” (168). From this perspective, Soulsbornes actively reinforce late-stage capitalism and its associated inequities while aligning with what Chris Paul calls “meritocratic game design,” a design practice that “teaches players that the only way to succeed is based on their own talent and effort, eliminating concerns about the structural issues surrounding access” (61). Other works that view the Soulsborne series as objects of reification include Jodi A. Byrd and Steven Harvie.

The political praxis group views Soulsbornes as participating in an aesthetic project that activates a certain political consciousness. For instance, Marco Caracciolo suggests that Dark Souls and Elden Ring’s “asynchronous multiplayer and constrained communication […] foster[s] community building in ways that depart from the shallowness and toxicity often associated with mainstream gaming culture’ (7). Likewise, Paolo Xavier Machado Menuez argues, “the Dark Souls series expresses in allegorical form an anxiety about living in a time where the meaning of our everyday actions and even society itself has become” estranged from our everyday actions (1), which he connects to the material condition of post-War Japan. Finally, DA Hall (2025) suggests the Soulsborne genre engages in a “strip-tease storytelling style” that calls a community “into being by only providing the possibility of partial perspectives, and by insisting on the partiality of those perspectives” (5). Other works that view Dark Souls and the Soulsborne series as an object of political critique include those of Daniel Illeger and Mateusz Felczak.

As with any critical taxonomy, these monikers do not capture the full complexity of each intervention. For example, Dooghan acknowledges that some players build community within Dark Souls (167), while Hall admits that segments of the Soulsborne community are toxic (25). Further, texts such as Timothy Welsh’s “(Re)mastering Dark Souls” exemplify a hybrid view, arguing that playing Dark Souls can both reflect and challenge neoliberal gamification. The ideological reification and political praxis monikers should therefore be seen as general categories and not rigid divisions.

Importantly, these divergent interpretations of Dark Souls reveal that any reading of a videogame is informed by each player-critic’s positionality. While this article is aligned with the political praxis group, my reading is informed by my own player experience and positionality—that of a U.S.-based, white, cis-male game studies scholar whose research focuses on critical race game studies. While I have grounded my reading of Dark Souls in videogame formalism and shown how the therapeutic response is a widespread phenomenon, my reading remains influenced by my player-critic positionality. With these limitations in mind, this article builds on these scholarly conversations by applying a videogame formalist analysis of Dark Souls to show how the videogame’s ludic-textual structures encourage a practice of hyperlinking and curate a networked community—transforming Dark Souls into the exemplary networked hyperlinked videogame.

A Videogame Formalist Analysis of the Ludic-Textual Structures in Dark Souls

Videogame formalism asks the player-critic to look at the various structural elements within a work and determine which qualify as “devices, meaning […] they are no longer automatized, and instead the player’s attention is drawn to them through a process of defamiliarization” (Mitchell and van Vught 124). While Mitchell and van Vught use the term devices, I prefer ludic-textual structures as a shorthand moniker to describe the different systems within a videogame that are defamiliarized and encourage player contemplation. Game studies has already offered a variety of different terms to describe a videogame’s structures: Hunicke et al.’s (2004) MDA model (mechanics, dynamics, and aesthetics), Järvinen’s (2007) nine categories of game elements, and Mitchell et al.’s (2020) poetic devices are all popular examples. However, the term ludic-textual structures draws attention to how the devices within a videogame serve both gameplay and textual functions. This is an active refusal of the narratology versus ludology debate that informed the establishment of game studies as a field and continues to haunt many of the methodological (Patrick Jagoda and Jennifer Malkowski 2022), gendered (Amanda Phillips 2020), and racial (Austin Anderson 2025) dimensions of game studies today. Finally, I want to make it clear that these ludic-textual structures do not operate in isolation and are instead interlocking systems that make up the whole of a videogame.

While numerous ludic-textual structures could be analyzed, I focus on three central ones within Dark Souls: (1) narrative elements, (2) mechanical difficulty, and (3) the networked multiplayer system. Throughout this section, I draw attention to how different structures within Dark Souls defamiliarize videogame play and encourage hyperlinking. This occurs because Dark Souls presents each of these ludic-textual structures with minimal direct explanation, yet each is foundational to successfully playing the videogame. The play experience estranges the player and “de-habitualize[s] automated forms of seeing and cognition thus renewing our relation to language/art and […] the world” (Holger Pötzsch). As such, Dark Souls pushes players towards paratextual materials such as guides, wikis, and lore videos to make sense of the videogame’s ludic-textual structures—an act I call hyperlinking. This hyperlinking practice is integral to the game’s curation of community, which “makes it possible for players to share and simultaneously clarify the personal or cultural significance of the games through collective meaning making” (Caracciolo 84).

Dark Souls’ first major ludic-textual structure is its narrative elements, which are the different narrative techniques that communicate the game’s plot, backstory, worldbuilding, and lore details.7 While the backstory is established during a brief opening cutscene where players learn that the First Flame that has sustained the Age of Fire is fading away, cutscenes or expository dialogue are rare in the rest of the game. Instead, Dark Souls’ narrative elements are primarily delivered through what Henry Jenkins calls “environmental storytelling”, which is a storytelling technique that creates “the preconditions for an immersive narrative experience” through spatial orientation and other interactive narrative techniques. In Dark Souls, these techniques include unreliable NPC narration, lore details told through item descriptions, and the mise-en-scëne of enemy/item placement in narratively contextual locations. Most of these narrative elements are optional; even seemingly critical information like the game’s overarching plot—which follows the player character’s attempt to either continue the Age of Fire or usher in the Age of Dark—is famously difficult to parse out and “must be deduced by the players themselves” (Franziska Ascher). In other words, Dark Souls defamiliarizes its narrative information.

As a result, Dark Souls encourages “an ‘archaeological’ mode of fandom”, where “the game’s narrative rewards careful reconstruction and even speculation” (Caracciolo 21). In practice, this “archaeological fandom” is achieved by a hyperlinking practice where players explore the in-game narrative elements via different item descriptions as well as various fan-made paratextual materials to try and understand the defamiliarized narrative. For instance, the game’s narrative ambiguity requires players to read through various item descriptions to parse out the game’s lore, and this practice has given rise to a robust interpretative community of “lore hunters” who specialize in decoding the game’s narrative and sharing their findings online. YouTubers like VaatiVidya and SmoughTown produce detailed accounts of the game’s characters, and these creators pull from the collective knowledge of the fandom while engaging in a “collective knowledge-building process in which fan theories blur the line between commentary, interpretation, and fan fiction” (Caracciolo 21).

Yet, Dark Souls also ensures that no narrative interpretation is “capable of becoming canonical, that is to say, of bearing the weight of the authority of truth” (Hall 12). This incites debate and encourages the player-critic to engage with a variety of fan-made paratextual materials first to understand and then to debate the game’s narrative elements. Therefore, Dark Souls’ defamiliarized narrative presentation is a key ludic-textual structure that encourages hyperlinking practices where players oscillate between the game and its paratextual ecosystem to produce an interpretation that no single playthrough or player can deliver. In doing so, players enter a networked discourse organized around interpreting the game’s narrative.

The second ludic-textual structure is the game’s mechanical difficulty, which is the most recognizable feature of Dark Souls and the larger Soulsborne genre. However, this difficulty is not based on fast-twitch reflexes like in Tekken (1994) nor frame-perfect inputs like in Super Meat Boy (2010). Rather, Dark Souls features a slow, deliberate combat system that requires careful response from the player. Enemies telegraph their attacks with clear visual cues, and the player is expected to respond by dodging, parrying, or counterattacking. Once players learn the language of the enemy’s attack patterns, Dark Souls becomes significantly easier to manage. This is reflected in the game’s enemy placement, as extremely challenging early-game bosses like The Capra Demon will eventually become regular enemies that the player easily overcomes.

Instead, much of Dark Souls’ difficulty comes from the way that its gameplay mechanics are presented—or, better said, not presented. In his videogame formalist reading of the controller configuration of This War of Mine (2014), Holger Pötzsch points out that the game’s “lack of tutorial deliberately prolongs the process of habitualisation of game controls and mechanics to draw attention to the unpreparedness of civilians to efficiently deal with a war situation,” and he contrasts this game with “mainstream games” that offer clear tutorials because the controller configurations are “treated as obstacle to be overcome as quickly as possible to enable a smooth enjoyment of the game.” Dark Souls operates under similar slides as the opening Undead Asylum area only includes a few optional tutorial messages that can only be engaged with by pressing the on-screen message icon; these messages provide basic instruction like the button configurations of the heavy attack, light attack, dodge, and parry. Otherwise, players must learn through trial-and-error or by seeking out online materials. Daniel Vella mentions how Dark Souls’ “elevated kinaesthetic difficulty” prevents “the player from obtaining complete knowledge of its cosmos,” and this has the effect of defamiliarizing gameplay mechanics. This, in turn, draws players to seek out clarification around gameplay mechanics in various paratextual materials such as YouTube guides or Wikis.

While scholars like Dooghan call the game “dispiritingly difficult” and suggest that the game’s mechanics “offer a radical simulation of personal responsibility” because of the effort required to master the combat system (152; 161), this overlooks how the game’s mechanical difficulty pushes players to engage with its other ludic-textual systems—particularly its multiplayer options—and community-made paratextual materials to ease said difficultly. In other words, the game’s difficulty encourages players to enter a community. Further, Tom Van Nuenen’s claim that Dark Souls is part of a lineage of games “fondly remembered […] because of their difficulty” like “classic platform games such as Battletoads (1991), Contra (1987), or Mega Man (1987)” (511) similarly overlooks the many options that Dark Souls offers to mitigate its difficulty—principally, its multiplayer system, which brings us to our final ludic-textual structure.

The third and final ludic-textual structure that demands extended attention is Dark Souls’ multiplayer system. While Dark Souls only has a single-player campaign, the experience is fundamentally shaped by its various synchronous and asynchronous multiplayer systems such as summoning, the message system, bloodstains, and illusionary phantoms.8 Using special items, players may summon other real players and NPCs into their gameworld for cooperative or competitive play. The game’s messaging system allows players to leave short notes for each other from a limited lexicon of words and phrases, and these notes have developed an entire in-game discourse where messages are helpful, joking, playful, or deceptive. Each player’s campaign is populated with various bloodstains, which, when interacted with, show the final few seconds of other players’ deaths. Finally, other players will periodically appear as non-interactable and nearly translucent phantoms that show other players’ simultaneous actions. While players can disengage with these systems by disconnecting from the game’s networked server, the game is designed to be played with these multiplayer elements enabled.

Like the other ludic-textual structures explored thus far, Dark Souls’ multiplayer systems are marked by the defamiliarization of the typical videogame’s multiplayer systems. None of these systems are well explained, which requires players to seek out digital resources to understand how these systems work. Further, the game’s multiplayer systems are primarily “asynchronous, indirect, or highly-restricted player interactions” (Matthew Kelly), and this limits the toxicity that is one of the defining traits of multiplayer games (Kishonna Gray). Take, for instance, the “famous anonymous user-generated notes posted throughout the world” (Kelly). This messaging system operates as “a constrained form of communication” where the player must “pick from a word list and arrange the terms within a fixed syntax” (Caracciolo 66). These constraints facilitate creativity and humor while also minimizing toxicity because hateful words or slurs are never possible in the messaging system. By defamiliarizing multiplayer videogame communication, players must develop a more positive relationship with multiplayer videogame play.

These multiplayer systems also curate what Ben Whaley calls connective engagement, which is a mode of play that opens “the game world up to a new sociality of play, beyond the atomized self of the individual player, by forging connections with other players in an indirect, sometimes virtual manner” (123). For instance, Kevin VanOrd describes how the bloodstains and illusory phantoms remind players that they are “part of a large multiverse” where other players are “part of a chorus of silent voices urging each other forward.” This ensures that “Dark Souls [is] a shared experience” where “no one person passes through Lordran unassisted” (Keza MacDonald and Jason Killingsworth 60). The game’s multiplayer systems defamiliarize videogame multiplayer engagement and push players to interact with a digital community to comprehend the multiplayer systems. Further, as will be explored in the next section, Dark Souls’ multiplayer systems operate as hyperlinks in themselves, which further supports the hyperlinking practice that the game encourages while curating a networked community.

While this article has only looked at three of Dark Souls’ defamiliarized ludic-textual structures, most of the game’s other structures produce a similar effect. For instance, the game features an intricate RPG system that impacts which weapons, spells, and/or armor the player character can use as well as their resistance to different enemy attack types. Yet, Dark Souls offers minimal in-game explanation and thus defamiliarizes RPG mechanics, which once again pushes players to adopt a hyperlinking practice to explore paratextual materials to decipher the game’s RPG systems.

What emerges through this hyperlinking practice is a robust networked community. YouTuber and longtime Souls community member EpicNameBro succinctly articulates this design philosophy:

[Dark Souls is] designed to make people talk about the game outside of the game. There is a reason there is not reliable communication in the game, it is to make people talk about and think about it outside of the game. The perfect game to build a community around.

Welsh cites this quote to argue, “the wikis, streams, forums, Discord servers and so on” enable “players to share and request assistance, are extensions of these in-game collaborative components.” Caracciolo similarly explains how Dark Souls’ “asynchronous and constrained-communication multiplayer work together with other aspects of the games’ design to foster more supportive forms of online collectivity than can be found elsewhere” (61). These online practices form “affinity spaces” where players “strategize, vent, joke, and even philosophize about their experiences” with these games (Bradley Robinson et al.). Through its defamiliarized ludic-textual structures, Dark Souls becomes a networked hyperlinked videogame and invites players to participate in its digital community.

To be clear, we must not “idealize FromSoftware fans, who are certainly not immune to the problematic competitiveness that […] affects large swathes of contemporary gaming” (Caracciolo 60). However, while a subset of players may engage in trolling or exclusionary behavior, the game’s design encourages collaboration, and Dark Souls director Hidetaka Miyazaki claims, “It [is] the greatest success of my career that a vibrant community has built up around the game I created” (qtd. Daniel Starkey). Further quantitative and qualitative research consistently shows that the Soulsborne online community rewards supportive player behavior (Van Nuenen) while “push[ing] against and resist[ing] these toxic technocultures” so common in videogame communities (Hall and Cunningham). In short, many Dark Souls and Soulsborne players seemingly understand that the game’s defamiliarized ludic-textual structures encourage collaborative player practices.

Close Playing Session of Ornstein and Smough Boss fight

This section turns to a close-playing analysis of the Ornstein and Smough Boss fight in Dark Souls. Drawing on my initial playthrough and online discussions of the boss fight, I explore how an example player, hereafter Player1, might tackle the notoriously challenging duo. The Ornstein and Smough boss fight occurs about halfway through the game when the player reaches Anor Londo, and it is considered “the first truly brutal boss encounter that Dark Souls players will battle” (Steven Richtmyer). Mitchell and van Vught explain that “difficulty can have a defamiliarizing function when either the difficulty level clearly deviates from the norm (i.e., becomes foregrounded), such as when the difficulty is much higher, or much lower (or even non-existent), than expected” (83). In the case of Ornstein and Smough, the defamiliarizing effect is produced by the large difficulty spike that occurs with the boss fight. A difficulty spike is when a videogame’s difficulty unexpectedly increases as opposed to the gradual increase in difficulty that most videogames offer. While difficulty spikes are often considered bad game design (Cristiano Politowski et al.) that invites player cheating or exploits in response (Mia Consalvo), the Ornstein and Smough difficulty spike defamiliarizes the player’s gameplay experience and encourages players to reconsider the gameplay approaches that they have thus far deployed in the game. This defamiliarization then encourages players to seek out alternative methods to defeat the encounter.

Ornstein and Smough is a two-enemy boss battle. While the earlier Bell Gargoyles boss fight similarly throws two enemies at the player, Ornstein and Smough are the first Dark Souls boss battle with two distinct opponents: Ornstein is quick and darts across the map with his spear, while Smough is plodding and swings his giant hammer down for powerful hits. This design decision disrupts the gameplay patterns that players have adopted while playing Dark Souls. For instance, Dark Souls allows players to dodge through enemy rolls by timing the dodge input against an enemy’s attack and using invisibility frames—or, i-frames—to roll through the attack. Since Ornstein and Smough attack the player simultaneously, quickly pressing the dodge input is no longer a viable strategy. Instead, players must slow down and carefully time their dodge against Ornstein and Smough’s simultaneous attacks.

Additionally, this is the first boss fight in the game that has two distinct phases with different health bars. In the first phase, both Ornstein and Smough have separate health bars at the bottom of the screen, which will decrease when the player attacks the corresponding enemy. Once a player has defeated either Ornstein or Smough, a cut scene will play where the defeated boss falls to the floor, while the surviving boss gains power from their fallen comrade. The second phase will see the player face an empowered version of Ornstein or Smough, determined by which one was left alive in the first phase. Like the difficulty spike, this design decision disrupts the gameplay pattern that players have thus far experienced: whittle the boss’s health bar to zero and receive the “Victory Achieved” message on screen. Instead, the player successfully defeats Ornstein or Smough, only to be greeted with a second phase.

These design decisions make it likely that Player1 cannot defeat Ornstein and Smough through solo gameplay, at least not on their first playthrough. As such, they will likely consider a variety of options to overcome the challenge such as using the game’s summoning system and/or searching paratextual guides to discover tips on defeating the duo. The summoning system itself functions akin to a series of hyperlinks. For instance, in Figure 4, several summon signs appear near the closest bonfire checkpoint to the Ornstein and Smough boss fight arena. If Player1 stands over any of these summon signs, Player1 can see the outline of a summonable player, who we will call Player2. While Player1 can view Player2’s avatar and gamename, Player1 is given no further information about Player2’s skill level or stats. Only by clicking the summon sign of Player2 can Player1 learn more information about their summon partner. Summoning requires a leap of faith and simulates pressing a “click here” hyperlink on the web. Further, there are usually multiple summon signs available near any boss fight, so Player1 may choose among many potential summoning partners: Player3, Player4, etc. To engage in cooperative play in Dark Souls, player1 selects a summon partner from a series of hyperlinks, which then allows the new companions to try and defeat Ornstein and Smough together, and player1 has been encouraged to engage in this system by the defamiliarized difficulty produced by the Ornstein and Smough boss fight.

Further, not all summons are other players as NPCs are sometimes available for summoning at specific boss fights, and the NPC Solaire can be summoned to assist a player with Ornstein and Smough. Here, Dark Souls uses its narrative to remind the player of this ability. When Player1 first arrived in Anor Londo where the Ornstein and Smough fight takes place, they met Solaire near the bonfire checkpoint, and he told Player1, “Anytime you see my brilliantly shining signature, do not hesitate to call upon me. You’ve left me with quite an impression. I would relish a chance to assist you.” Dark Souls’ narrative is actively reminding players about the game’s multiplayer system. Later, Solaire’s summon sign can be found near the Ornstein and Smough fight arena, and he can assist any player who chooses to summon him. Here, the game’s design—both the Ornstein and Smough difficulty spike and the dialogue of Solaire—encourages Player1 to engage in the hyperlinking summoning system to overcome the challenging and defamiliarized Ornstein and Smough boss fight. In this instance, the game’s narrative pairs with its mechanical difficulty to encourage the hyperlinking practice that builds collaborative play.

Importantly, this hyperlinking practice supports community formation. In one of the earliest reviews of Dark Souls, VanOrd recognized the importance of the game’s summoning system for the overarching gameplay experience, and he describes how the brute difficulty of Dark Souls’ single-player campaign and its unique networked elements create an “unusual and wonderful contradiction”, where “you feel remarkably alone in this frightening place, yet simultaneously part of a large multiverse where simply playing the game makes you part of a chorus of silent voices urging each other forward.” Dark Souls pairs the practice of hyperlinking with its participatory multiplayer network to cultivate a community that can collectively overcome the game’s challenges. This is also seen in how the game encourages players to engage with fan-made paratextual materials.

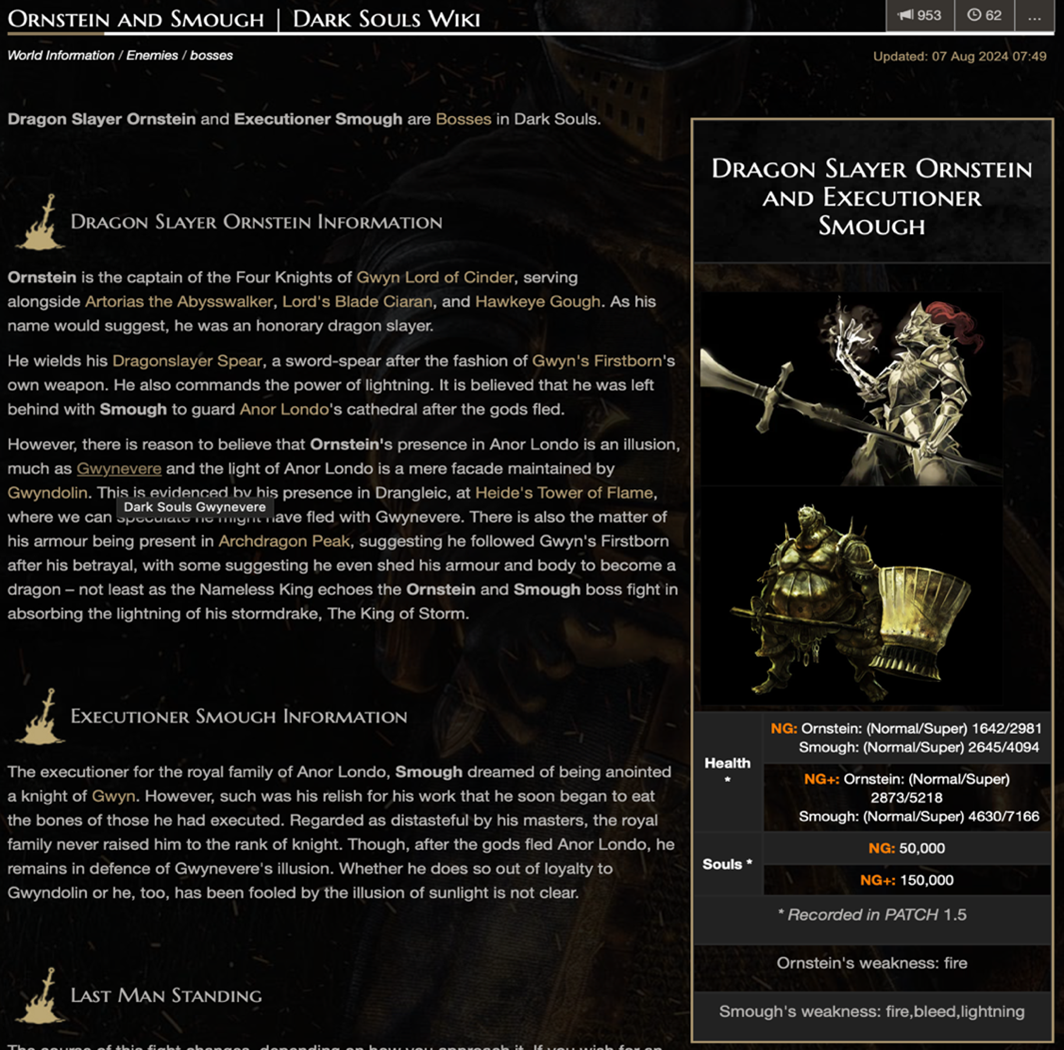

These wikis feature numerous hyperlinks: 13 are visible in Figure 5 alone and there are 71 total on the entire Ornstein and Smough wiki page. Players are invited to click these different links, and this becomes a game-in-itself where players attempt to parse out the hidden meaning behind various NPCs or weapons. For instance, Player1 might review the Ornstein and Smough wiki page and notice the name “Gwen”, a character they have likely heard much about at this point in the game but have not directly encountered. Clicking this hyperlink takes Player1 to Gwen’s homepage, and Player1 might then click on the hyperlink titled “Kiln of the First Flame” where they see a potential armor set called the “Black Knight Set”. Upon arriving at the “Black Night Set” homepage, Player1 might see the page for the “Twinklingly Titanite” upgrade material for the armor set. Player1 has entered the Dark Souls wiki rabbit hole where a player enters the wiki to learn one specific thing about the game but ends up staying in the paratextual digital world and learning much more about the larger Dark Souls universe. These hyperlinks function as a foundational aspect of Dark Souls because the game’s various defamiliarized ludic-textual structures have curated a player response that will drive them to search these materials.

In short, Dark Souls is a game that demands a strategy guide, which players find by searching websites and thus the Soulsborne games craft online communities of gamers seeking to navigate the brutal difficulty of the gameworld. This hyperlinking practice actively supports the curation of the networked digital community that lies at the heart of the Dark Souls experience: the collaboratively built Fextralife Dark Souls wiki, the Dark Souls fandom wiki, and the SoulsLore website; the lore videos from VaatiVidya and SmoughTown; the exploration of the game’s source code from Zullie the Witch; and the experimental playthroughs of gamers like Iron Pineapple, LilAggy, and the Backlogs are all key parts of the Soulsborne networked community. This close playing analysis of the Ornstein and Smough boss fight has offered a key insight into how Dark Souls encourages a hyperlinking practice, which, in turn, creates this vibrant networked community.

Conclusion and Futures for the Networked Hyperlinked Videogame

Throughout this article, I have applied a videogame formalist analysis to Dark Souls in order to define the networked hyperlinked videogame, which is a videogame that defamiliarizes videogame play to encourage a hyperlinking practice and build a networked community. Given that “what makes the work meaningful is the result of the connections that the player has found between their aesthetic experience of the work and their lived experience outside of the work” (Mitchell and van Vught 107), this article began by looking at the therapeutic response that Dark Souls has curated in many players. The article’s literature review drew our attention to how videogame formalism is informed by the differing situated knowledge of players. The article then explored how Dark Souls’ ludic-textual structures defamiliarize videogame play. Finally, it offered a close playing analysis of the Ornstein and Smough boss fight to explore how the game’s defamiliarized gameplay encourages a hyperlinking practice that, in turn, curates a networked community.

As with any new term, the networked hyperlinked videogame is provisional, and there are multiple areas for further research. For instance, I have not explored how the networked hyperlinked videogame relates to the intertextuality of other videogames and media. If we accept Janet Murray’s argument that “literary works are hypertextual in their allusions to one another” (56), then the networked hyperlinked videogame can draw our attention to intertextual references in videogames. In the case of Dark Souls and the Soulsborne series, the games are filled to the brim with literary, architectural, and filmic illusions; for instance, Nito from Dark Souls invokes Akira Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood while Igon in Elden Ring: Shadow of the Erdtree is a clear reference to Captain Ahab in Herman Melville’s Moby Dick. These intertextual moments can likewise invite a hyperlinking player practice where players are drawn into digital interpretative communities, and more work is needed to explore how this works in practice.

Another area for further exploration is what happens when the defamiliarization effect is lost—be that from replaying the defamiliarized game or from its ludic-textual structures becoming commonplace in videogame design. Pötzsch points out that the formalists were “fully aware of the fact that estranging devices, once deployed, gradually wear off and become conventionalized thereby losing their effect, as such implying a constant oscillating between conventionalization and renewal”, and the same is true with the networked hyperlinked videogame. Welsh has already drawn our attention to how the player’s experience of playing Dark Souls—or any other videogame—changes depending on the specific moment in which it is played. Further, Dark Souls is one of the most influential videogames today with the rise of the Souls-like genre. What becomes of the networked hyperlinked videogame as Dark Souls is increasingly mainstream and its ludic-textual structures are incorporated into various videogames? These questions will need to be answered to understand the utility of the networked hyperlinked videogame as a descriptive term for game studies.

In the meantime, the networked hyperlinked videogame offers an important starting point to understand how the ludic-textual structures of videogames can defamiliarize videogame play and encourage specific player responses both within and beyond the game itself. As I have argued, these responses can actively curate a vibrant networked community around a videogame where the refamiliarization effort becomes an act of community formation. This is the generative work of Dark Souls and the networked hyperlinked video game, and it explains why players like Nakey Jakey, Writing on Games, and so many others say, “Thank you, Dark Souls.”

Works Cited

Adamic, Lada A., and Natalie Glance. “The Political Blogosphere and the 2004 U.S. Election.” Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop on Link Discovery - LinkKDD ‘05, 2005, pp. 36—43, https://doi.org/10.1145/1134271.1134277.

Anderson, Austin. “Gamic Grammar: Manufacturing Consent (to Whiteness) in Game Studies.” Journal of Gaming & Virtual Worlds, vol. 17, Consensual Play, Mar 2025, pp. 17 — 38. https://doi.org/10.1386/jgvw_00113_1.

Anderson, Sky LaRell. “Extraludic Narratives: Online Communities and Video Games.” Transformative Works and Cultures, vol. 28, 2018. https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2018.1255.

Ascher, Franziska. “Narration of Things: Storytelling in Dark Souls Via Item Descriptions.” First Person Scholar, 22 Apr. 2015, https://www.firstpersonscholar.com/narration-of-things/.

Bolter, Jay David. Writing Space: Computers, Hypertext, and the Remediation of Print. LEA. 2001.

Byrd, Jodi A. “‘Do They Not Have Rational Souls?’: Consolidation and Sovereignty in Digital New Worlds.” Settler Colonial Studies, vol. 6, no. 4, 2016, pp. 423-37. https://doi.org/10.1080/2201473X.2015.1090635.

Caracciolo, Marco. On Soulsring Worlds: Narrative Complexity, Digital Communities, and Interpretation in Dark Souls and Elden Ring. Routledge, 2024.

Ceranoglu, T. Atilla. “Video Games in Psychotherapy.” Review of General Psychology, vol. 14, no. 2, 2010, pp. 141—46. DOI: 10.1037/a0019439.

Ciccoricco, David. Reading Network Fiction. University of Alabama Press, 2007.

Consalvo, Mia. Cheating: Gaining Advantage in Videogames. MIT Press, 2007.

Dark Souls: Remastered. Directed by Hidetaka Miyazaki, FromSoftware, 2018 [2011]. Xbox Series X.

De Maeyer, Juliette. “Towards a Hyperlinked Society: A Critical Review of Link Studies.” New Media & Society, vol. 15, no. 5, Dec. 2012, pp. 737—51, https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444812462851.

Dooghan, Daniel. “Fantasies of Adequacy: Mythologies of Capital in Dark Souls.” Games and Culture, SAGE Publishing, Aug. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1177/15554120231192080. Sage Journals.

Ember. “Dark Souls Saved My Life” YouTube, uploaded by Ember, 9 Dec. 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ABV_7BEslX8.

Ensslin, Astrid. “Hypertext Theory.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia. Oxford, 31 Mar. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.013.982.

EpicNameBro. “Let’s Play Dark Souls: From the Dark Part 19.”YouTube, 23 Aug. 2015, www.youtube.com/watch?v=yGe6-2PuWM4. Accessed 14 Dec. 2024.

Erlich, Victor. Russian Formalism: History and Doctrine. Yale UP, 1981.

Felczak, Mateusz. “The ‘Git Gud’ Fallacy: Challenge and Difficulty in Elden Ring.” Game Studies, vol. 25, Mar. 2025. https://gamestudies.org/2501/articles/mateusz_felczak.

Franco, G. E. “Videogames and Therapy: A Narrative Review of Recent Publication and Application to Treatment.” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 7, 2016. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01085.

“FromSoftware.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/FromSoftware. Accessed 2 Jul. 2025.

Gandolfi, Enrico. “Enjoying Death Among Gamers, Viewers, and Users: A Network Visualization of Dark Souls 3’s Trends on Twitch.tv and Steam Platforms.” Information Visualizations, vol. 17, no. 3. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473871617717075.

Gray, Kishonna L. Race, Gender, and Deviance in Xbox Live: Theoretical Perspectives from the Virtual Margins. Routledge, 2014.

Hall, DA. “A Beginner’s Guide to Painted Worlds: The Haunted Mansion, Dark Souls III, and the Playground of Interpretation.” Proceedings of DiGRA 2024, pp. 1-18. https://dl.digra.org/index.php/dl/article/view/2238/2235.

---. “The Fallen Leaves Tell a Story: Elden Ring and the Emergence of the Soulslike Genre.” Emerging Genres: New Formations of Games, edited by Joshua Call et al., 2025.

Hall, DA, and Kyle Cunningham. “The Lands Between: Communities of Difference and Algorithmic Resistance around FromSoftware’s Elden Ring.” Att-F4: Rebuilding Community after Gamergate, 2024.

Harvie, Steven. “Roguelites, Neoliberalism, and Social Media.” First Person Scholars, 14 Oct. 2020, <www.firstpersonscholar.com/roguelites-neoliberalism-and-social-media>.

Hines, Mark. “‘A Crown is Warranted With Strength’: Bosses, Fantasy, and Democracy in Elden Ring.” Games and Culture, vol 19, no. 8. https://doi.org/10.1177/15554120231186476.

Hunicke, R., et al. “MDA: A Formal Approach to Game Design and Game Research.” In Proceedings of the AAAI Workshop on Challenges in Game AI, vol. 4, no. 1, 2004.

Illeger, Daniel. “The Lifelike Death: Dark Souls and the Dialectics in Black.” Eludamos: Journal for Computer Game Culture, vol. 11, no. 1, 2020, pp. 111—23. https://doi.org/10.7557/23.6357

Indie Bytes. “Don’t You Dare Go Hollow — Dark Souls As An Allegory for Depression.” YouTube, uploaded by Indie Bytes, 19 Jan. 2016.

Jagoda, Patrick and Jennifer Malkowski (eds.), American Game Studies, special issue of American Literature, vol. 94, no. 1, Duke UP, Mar. 2022.

Järvinen, Aki. “Introducing Applied Ludology: Hands-on Methods for Game Studies.” In Situated Play, Proceedings of DiGRA 2007 Conference, 2007.

Jenkins, Henry. “Game Design as Narrative Architecture.” Electronic Book Review, 10 Jul. 2004, https://electronicbookreview.com/essay/game-design-as-narrative-architecture/.

Juul, Jesper. Half-Real. MIT Press, 2005.

Kelly, Matthew. “I Can’t Take This: Dark Souls, Vulnerability, and the Ethics of Networks.” First Person Scholar, May 2016, <www.firstpersonscholar.com/i-cant-take-this/>. Accessed 14 Dec. 2024.

Kunzelman, Cameron. “How We Deal with Dark Souls: The Aesthetic Category as a Method.” Hybrid Play, edited by Adriana de Souza e Silva and Ragan Glover-Rijkse, Routledge: Crossing Boundaries in Game Design, Players Identities and Play Spaces, 2020.

Landow, George. Hypertext: The Convergence of Contemporary Critical Theory and Technology. John Hopkins UP, 1991.

MacDonald, Keza and Jason Killingsworth. You Died: The Dark Souls Companion. Gardners, 2016.

Marcostbo. “Seeing this place like that makes me really happy.” Reddit, https://www.reddit.com/r/darksouls/comments/qd5d9b/seeing_this_place_like_that_makes_me_really_happy/.

Matačinskaitė, Jurgita. “The Internet as a ‘Public Sphere.’” Žurnalistikos Tyrimai, vol. 4, Jan. 2011, pp. 88—105, https://doi.org/10.15388/zt/jr.2011.4.1788.

Mitchell, Alex and Jasper van Vught. Videogame Formalism: On Form, Aesthetic Experience and Methodology. Amsterdam University Press, 2023.

Mitchell, Alex. “Making the Familiar Unfamiliar: Techniques for Creating Poetic Gameplay.” Proceedings of 1^st^ International Joint Conference of DiGRA and FDG, 2016, pp. 1-16. https://dl.digra.org/index.php/dl/article/view/774/774.

---, et. al. “A Preliminary Categorization of Techniques for Creating Poetic Gameplay.” Game Studies, vol. 20, no. 20, 2020. https://gamestudies.org/2020/articles/mitchell_kway_neo_sim.

Mortensen, Torill and Kristine Jorgensen. The Paradox of Transgression in Games. Routledge, 2020.

Murray, Janet. Hamlet on the Holodeck. The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace. MIT Press, 1997.

Nakey Jakey. “Dark Souls Saved Me.” YouTube, uploaded by Nakey Jakey, 20 Jan. 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iSJkxLdIlyE.

“Ornstein and Smough - Dark Souls.” Dark Souls Wiki, 2019, https://darksouls.wiki.fextralife.com/Ornstein+and+Smough. Accessed 14 Dec. 2024.

Papacharissi, Zizi. “The Virtual Sphere: The Internet as a Public Sphere.” New Media & Society, vol. 4, no. 1, Feb. 2002, pp. 9—27, https://doi.org/10.1177/14614440222226244.

Park, Han Woo, and Mike Thelwall. “Hyperlink Analyses of the World Wide Web: A Review.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, vol. 8, no. 4, June 2006, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2003.tb00223.x.

Parker, Jeff. “A Poetics of the Link.” https://Electronicbookreview.com/Essay/A-Poetics-of-The-Link/, Sept. 2001, www.altx.com/ebr/ebr12/park/park.htm. Accessed 14 Dec. 2024.

Paul, Chris. The Toxic Meritocracy of Video Games Why Gaming Culture Is the Worst. University of Minnesota Press, 2018.

Phillips, Amanda. Gamer Trouble: Feminist Confrontations in Digital Culture. NYU P, 2020.

Politowski, Cristiano, et al. “Assessing Video Game Balance using Autonomous Agents.” In IEEE/ACM 7th International Workshop on Games and Software Engineering (GAS), 2023. DOI: <10.1109/GAS59301.2023.00011>.

Pötzsch, Holger. “Playing Games with Shklovsky, Brecht, and Boal: Ostranenie, V-Effect, and Spect-Actors as Analytical Tools for Game Studies.” Game Studies, vol. 17, no. 2, Dec. 2017. https://gamestudies.org/1702/articles/potzsch.

Rasmussen, Terje. “Internet and the Political Public Sphere.” Sociology Compass, vol. 8, no. 12, Dec. 2014, pp. 1315—29, https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12228.

Rettberg, Scott. “The Pleasure (and Pain) of Link Poetics.” Electronic Book Review, 10 Jan. 2002, https://electronicbookreview.com/essay/the-pleasure-and-pain-of-link-poetics/.

Richtmyer, Steven. “Dark Souls’ Toughest Boss.” ScreenRant, Screen Rant, 28 Aug. 2020, https://screenrant.com/dark-souls-ornstein-smough-boss-fight-easy-win/. Accessed 14 Dec. 2024.

Robinson, Bradley, et al. “‘I Think I Get Why Y’all Do This Now’: Reckoning with Elden Ring’s Difficulty in an Online Affinity Space.” Games and Culture, Oct. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1177/15554120231203134. Sage Journals.

Shklovsky, Viktor. “Art as Technique.” Modern Criticism and Theory: A Reader, edited by David Lodge pp. 16-30. Longman 1988.

Sköld, Olle. “Getting-to-Know: Inquiries, Sources, Methods, and the Production of Knowledge on a Videogame Wiki.” Journal of Documentation, vol. 73, no. 6, Oct. 2017, pp. 1299-1321. DOI: 10.1108/JD-11-2016-0145.

Starkey, Daniel. “Dark Souls III Is Brutally Hard, But You’ll Keep Playing Anyway,” Wired, 4 Apr. 2016, <www.wired.com/2016/04/dark-souls-iii-review/>.

Švelch, Jan. “Paratextuality in Game Studies: A Theoretical Review and Citation Analysis.” Game Studies, vol. 20, no. 2, Jun. 2020. https://gamestudies.org/2002/articles/jan_svelch.

Thompson, Kristin. Breaking the Glass Armor: Neoformalist Film Analysis. Princeton University Press. 1988.

Turow, Joseph. “Introduction: On Not Taking the Hyperlink for Granted.” The Hyperlinked Society Questioning Connections in the Digital Age, edited by Joseph Turow and Lokman Tsui, University of Michigan Press, 2009, pp. 1—18.

van Nuenen, Tom. “Playing the Panopticon: Procedural Surveillance in Dark Souls.” Games and Culture, vol. 11, no. 5, July 2016, pp. 510—527, https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412015570967.

VanOrd, Kevin. “Dark Souls Review.” GameSpot, 3 Oct. 2011, <www.gamespot.com/reviews/dark-souls-review/1900-6337624/>. Accessed 14 Dec. 2024.

Vella, Daniel. “No Mastery without Mystery: Dark Souls and the Ludic Sublime.” Game Studies, vol. 15, no. 1, July 2015, https://gamestudies.org/1501/articles/vella.

Welsh, Timothy. “(Re)Mastering Dark Souls.” Game Studies, vol. 20, no. 4, Dec. 2020, https://gamestudies.org/2004/articles/welsh.

Whaley, Ben. Toward a Gameic World: New Rules of Engagement from Japanese Video Games. U of Michigan P, 2023.

Writing On Games. “Dark Souls Helped Me Cope With Suicidal Depression” YouTube, uploaded by Writing On Games, 20 Jan. 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=viP4psS3MUQ.

Xavier Machado Menuez, Paolo. The Downward Spiral: Postmodern Consciousness as Buddhist Metaphysics in the Dark Souls Video Game Series. 2017, https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds/4161/.

Footnotes

-

Souls-like and Soulsborne are often used interchangeably. For instance, Cameron Kunzelman claims, “Soulsborne is a portmanteau of Dark Souls and Bloodborne, two FromSoftware games directed by Hidetaka Miyazaki that share a design sensibility,” and he suggests that “Souls-like” and “soulsborne” can be used interchangeably (191); Bradley Robinson et al. similarly claim, “a Soulsborne, or Soulslike, game is one created by, or inspired by the work of, Hidetaka Miyazaki” (317). Yet, as DA Hall (2025) forcibly points out, “souls-like” and “soulsborne” are quite distinct. The Soulsborne is the career-spanning artistic project of Hidetaka Miyazaki and FromSoftware that contains a unique “spatio-temporal structure” within its narrative and gameplay while a Souls-like is non-FromSoftware videogame mechanically and/or narratively inspired by the Soulsborne series such as Hollow Knight (2017), Lies of P (2023), and Dead Cells (2018). Following Hall’s terminology, I view Soulsbornes as an artistic project rather than a genre. ↩

-

While Mitchell and van Vught’s videogame formalism begins from their own play experience with a videogame, I have begun with the therapeutic response from Nakey Jakey and other player-critics because it both aligns with my own initial playthrough and reveals the pervasiveness of this response. ↩

-

I am using the term defamiliarization throughout this essay, but this term has a contested history. Viktor Shklovsky coined the term “ostranenie” in his 1919 essay “Iskusstvo Kak Priem.” Holger Pötzsch points out, “there is no complete agreement among scholars as to how exactly Shklovsky’s neologism ostranenie should be translated,” and the term has been translated to various terms such as “making strange,” “estrangement,” and “defamiliarization.” I use defamiliarization since it is the term used by Mitchell and van Vught. ↩

-

Throughout this essay, I use the terms paratext and paratextual materials to refer to supplemental materials related to Dark Souls, such as lore videos, fan wikis, gameplay guides, and community forum posts. Jan Švelch points out that “paratext” can refer to “Any element that forms a figurative threshold of a text and grounds it in a socio-historical context.” In my usage, I focus on fan-made paratexts, rather than the “paratextual industry” described by Mia Consalvo, in that they are not produced or sanctioned by FromSoftware. While I recognize that some scholars caution against overextending the term (Švelch), I use paratext as a practical shorthand for this corpus of fan-created, interpretive materials that orbit and inform the game. ↩

-

Jeff Parker writes, “Instead of thinking of the link as the connector between two nodes, consider it a space one has to cross and fill to get to the next node, an empty node between two already full nodes.” ↩

-

The Russian Formalism tradition from which videogame formalism emerges was influenced by Edmund Husserl’s phenomenology, which acknowledged “that phenomena can only be studied from one’s lived experience whereby knowledge of the phenomenon can never be considered objective but can be shared between different subjects who roughly share a system of intersubjective standards or (historical and cultural) backgrounds” (Victor Erlich 62, qtd. Mitchell and van Vught 65). ↩

-

We must be cognizant of how contested the term “narrative” is in game studies (see, among many others, Jesper Juul 156). I use “narrative” as a shorthand for the elements that communicate Dark Souls’ narrative elements in some way. ↩

-

There are also lesser-known multiplayer elements such as Bonfire Kindling, Shared Events, Miracle Resonance, and Vagrants. All of these occur when a single player does an action in their gameworld (e.g., casting certain “Miracles,” a type of spell in the game or upgrading the Bonfire checkpoint system through “kindling”) gives benefits to other players’ gameworlds on “nearby” networks. These events are rare occurrences, but their integration into the game further highlights the interconnection between the single-player campaign and the game’s asynchronous multiplayer elements. ↩

Cite this article

Anderson, Austin. "Dark Souls as Networked Hyperlinked Videogame" Electronic Book Review, 28 September 2025, https://electronicbookreview.com/publications/dark-souls-as-networked-hyperlinked-videogame/