"These Waves ...:" Writing New Bodies for Applied E-literature Studies

Against the backdrop of écriture feminine and e-lit texts, Ensslin et. al advance methods and findings of the "Writing New Bodies" project (“WNB”; SSHRC IG 435-2018-1036; Ensslin, Rice, Riley, Bailey, Fowlie, Munro, Perram, and Wilks) to lay the foundations of Applied E-literature Research. Their aim is to develop a digital fiction for a new form of contemporary, digital-born bibliotherapy. In following the principles of critical community co-design and feminist participatory action research, WNB engages young woman-identified and gender nonconforming individuals ages eighteen to twenty-five in envisioning worlds where they feel at home in their bodies. The workshops encourage them to engage, conversationally and through reading, co-designing and writing digital fiction, with key challenges facing young women today, including cis- and heteronormative gender relations, racism, anti-fat attitudes, ableism, and familial influences on the ways young women “ought to look” (Rice). This essay originally appeared as a keynote at the 2019 ELO conference in Cork, delivered by Ensslin.

1.Riding the Waves (Generations) of E-lit Practice and Scholarship

In recent years, there has been a lot of talk on waves in electronic literature (“e-lit”) or, more specifically, on “generations” of creative practice, and on “waves” of e-lit scholarship. In 2002, N. Katherine Hayles introduced the concept of second generation hypermedia, characterized by their distinctive multimodality, and enabled by newly evolving, browser-based editing and network technologies vis-a-vis stand-alone, first generation, pre-web hypertext works, which were largely monomodal-verbal and followed a somewhat bookish aesthetic. This generational shift took place around 1995 (Hayles, “Keynote”), with Jackson’s Patchwork Girl marking the “appropriate culminating work” (Hayles, Electronic Literature 7). It is important to realize that, as with all generational shifts, this one did not mark a radical break in creative practice. Rather, it marked the beginning of a newly evolving aesthetic development driven by technological change. In other words, all e-lit generations are overlapping, they co-exist, respond to and feed off one another - similar to, and perhaps as contested as, the so-called waves of feminism.

In Canonizing Hypertext: Explorations and Constructions, Ensslin took inspiration from the growth of ludic e-lit that foregrounds machinic agency vis-a-vis that of the player-reader, and proposed the term “cybertext” (adapted from Aarseth) to mark a “third generation” that later led to a full-fledged theory of literary gaming (Ensslin, Literary Gaming). Subsequently, in Digital Litteratur, Hans Kristian Rustad coined the term “fourth generation social media literature,” which reflects the participatory nature of Web 2.0 literary co-production and foregrounds platform and sociality as significant aspects of aesthetic expression and meaning-making. This fourth generation venture into popular, freely available platforms and participatory culture is also reflected in Leonardo Flores’ recently proposed “third generation e-lit.” For Flores, third generation e-lit, starting from around 2005, uses established mass platforms such as Twitter and Instagram in innovative, uniquely expressive ways to create new forms of e-lit for mass audiences, in contrast to the custom, niche-inhabiting interfaces of second generation e-lit, as he defines it.

Given the sheer explosion of technological developments, the generative turn in e-lit authorship, and the algorithmic turn in media and cultural theory (among many other developments in the mobile, AI and VR/AR sectors), the idea of fairly clear-cut “generations” has become less tangible in recent years. The blending wave metaphor may thus be more appropriate as it also connotes (dis)continuity. Be that as it may, this article is less concerned with waves of creative production. Rather, it aims to explore and document a new wave of scholarly engagement with e-lit, which we call “applied e-literature studies,” and which addresses social issues of our time heads-on.

The development of e-lit scholarship since the early 1990s has seen a shift from first wave hypertext theory, marked in particular by comparisons with print and ideas of convergence with poststructuralist concepts, to a second wave of “bottom up”, medium-specific “close-readings,” particularly in the works of digital fiction analysts and informed by theories and analytical tools of postclassical narratology, ludology, applied linguistics, critical code studies, and semiotics (starting around the mid-2000s). Spear-headed by pioneering early hypertext reader-response work done for example by David Miall and Teresa Dobson, and further refined by scholars like Anne Mangen, Adriaan van der Weel, Colin Gardner, James Pope, and, most recently, by the UK-based “Reading Digital Fiction” research group (Bell, Ensslin, van der Bom, and Smith; see also Ensslin, Bell, Skains, and van der Bom), a third wave of e-lit scholarship has been producing empirical insights into how readers perceive, process, and communicate experiences of multilinear reading, of hyperlinks and their projected meanings, of immersion and its multilayered, fluid phenomenology, and of the degrees to which reader-players may feel drawn into the storyworld when confronted with different forms and ambiguities of textual “you”.

All these waves of e-lit scholarship are no doubt flowing and evolving further on multiple levels. They inform, respond to, deviate from and build on one another, as well as generating the need for new waves that reach beyond their own disciplinary boundaries and into non-academic communities. We argue that electronic literature as a field has matured to a point where it cannot only radically innovate artistic expression and break down boundaries between historically separate art forms, but it can also disrupt and intervene in hegemonic platforms and the social practices associated with them. Flores’ concept of third generation e-lit indexes that the field has reached an important threshold, where popular and experimental cultures meet and where the peripheries move to the center. Scholars, students and teachers of e-lit today have a host of tools available that extend beyond offering platforms for popular, digital-born creative writing (Skains). What this new wave of accessibility also implies is that we as scholars can - more freely and creatively than ever before - re-purpose electronic writing in a kind of applied scholarly engagement that is designed to tackle social and planetary justice issues (see Tisseli). In the study reported here, applied e-lit research engages specific and subjugated communities in critical co-design, in direct collaboration with one or more e-lit artists and experts from other relevant fields.

2.Postfeminism and Appearance Culture

An appropriate starting point to applied e-literature studies is the examination of e-lit works that deal with highly specific, urgent social justice issues and to learn from them as inspirations for interventionist interaction and design. In the case of the present study, it thus makes sense to begin by examining some examples of the kinds of visual culture that reflect, represent, and evoke considerations and concerns about body image in appearance-centered, neoliberalist society. In this study, we are focusing in particular on young women’s body image, or, more precisely and inclusively, on body image in young, woman-identified and gender non-conforming individuals. This does not mean that those with other gender identifications do not have body image concerns worth looking into. Yet the statistics speak for themselves: studies conducted in many wealthy nations show how girls as young as six already express body dissatisfaction (Dohnt and Tiggemann); ten million women as opposed to one million men in the U.S. struggle with eating disorders on a daily basis, and twenty-five percent of women aged eighteen to twenty-one seek to manage their weight by regular bingeing and purging (The Renfrew Center Foundation for Eating Disorders). Existing studies also suggest that gender nonconforming young adults, especially those assigned female at birth (Diemer, White Hughto, Gordon, Guss, Austin, and Reisner) are at a particularly high risk for developing eating and body related distresses (Watson, Veale and Saewyc). These are just a few indicators of a pervasive social problem that affects female-identified and gender non-conforming youth, including those of various intersectional backgrounds in complex and diversely felt and mediatized ways.

Body image issues in young women can be understood against the backdrop of postfeminist sensibility (Gill, “Postfeminist”) and gendered appearance culture, where self-surveillance and body make-overs form part of women’s mechanisms of self-empowerment yet at the same time confirm the ideological constraints in which women’s ideas and ideals of self are entrenched (Riley, Evans, Elliott, Rice, and Marecek; Riley, Evans, and Robson). More specifically, whilst many women in Western society enjoy many of the liberties of self-determination and quasi-equality, unattainable desires for the perfect body continue to lead to body dissatisfaction, anxiety, low self-esteem, over-exercising, and yo-yo dieting (Grogan). The desire for external body approval starts with and is strongly shaped by parental and familial influences, which are reinforced concurrently and consecutively by peer pressure and media exposure; the learnings acquired from these and other relationships and contexts inhere and commingle to scaffold eating and body related concerns (Rice; LaMarre, Rice, and Rinaldi). The resulting desire typically leads to extensive self-monitoring and self-loathing, to the need to constantly perfect one’s body, but also to the illusion of having to meet the cruelly optimistic dictate to lead a healthy and therefore “good” life (Berlant; Chandler and Rice; Riley, Evans, and Robson).

Postfeminist media often represents living a good life in terms of appropriate consumption and work on the self and body, with the body presenting a good person and a good life (e.g. someone with the will power to work out regularly). This means we “read” the person in/through their appearance, making “looking” good critically important to being perceived as a good woman and person. Notions of self are aligned with the desire to meet cultural ideals of femininity in terms not just of signalling that one has achieved a (heterosexually attractive) appearance but also that they have worked to embody a certain idealized standard of personhood - one that is morally upright, self-contained, autonomous and productive (Rice, Chandler, Liddiard, Rinaldi, and Harrison). However, it is easy to get it wrong in a world of many choices, and an important element of postfeminism is requiring women to meet contradictory demands and expectations (Riley, Evans, and Robson). What women do to orient themselves in this maze of social contradictions is look at other women and get looked at (often judgmentally) in return, making looking a key regime of governance and self-management in postfeminism (Rice; Riley, Evans, and Mackiewicz).

3.Postmedia Bodies, Electronic Literature, and the Ergodic Gaze

Appearance culture is defined by the primacy of looking as a mode of interacting, at human and specifically women’s bodies, more commonly known as “the gaze” (Mulvey). The gaze comes in manifold forms, depending on who is being looked at and who is doing the looking. That being said, in our postmedia (Manovich), posthuman, postbiological world, bodies are hybrid, malleable and multiple and cannot be seen as a monolithic, stable entities. Online, we can mould and shape them to meet our innermost desires and address our deepest-felt anxieties. We can create countless bodies and enrich them with algorithmic, “post-cybernetic control” mechanisms (Parisi 105). These mechanisms provide us with greater insight into and awareness of our somatic processes but simultaneously expose our bodies, mostly subconsciously, to datafication and surveillance (see Blast Theory’s Karen app for an example of how e-lit may tackle this issue in immersive ways; see Chatzichristodoulou). Our digitalized bodies seem liberated from their first-world fleshliness. In digital media, we can distort and fragment our bodies and those of others as metaphors of cognitive dissonance and broken relationships with ourselves and others - as shown by the pixel-splintered wife’s body and the metaleptic webcam in Bouchardon’s and Volckaert’s Loss of Grasp (see Bell). We can stylize our digital bodies as idealized representations of our own narcissism, or as satirical permutations of those idealizations, which we find in Shelley and Pamela Jackson’s the doll games. These refashionings often leave our bodies simultaneously liberated and “alienated from themselves, augmented thanks to technology, modified, reincarnated, multiplied” (Brodesco and Giordano 11). And yet our bodies remain ensconced within Foucauldian dispositifs, in the kind of hegemonic power networks that make it near impossible to escape hypermediated toxicity, sexism, anti-fat attitudes, ableism, racism, and other appearance-centered forms of abuse that assume a holistic, deterministic notion of the body prone to binarist hate and othering.

The gaze, which forms the imagined or material starting point of unequal power relationships, is seductively malleable and can take on a variety of highly effective manifestations. The Mulvean, binarist male gaze, which assumes that women are the passive object of the active, male voyeur has been stretched, modulated, and augmented throughout the history of visual culture. The “looking relations” (Berger) we adopt as a way of naturalized looking and being looked-at are primed by the cultural gazes we are exposed to. Artistic responses to Edouard Manet’s famous oil painting, “Olympia” (1863), for example, engage with how women have been positioned as objects of various types of hegemonial gazes throughout the history of visual culture. In Manet’s painting, the conventional white female nude courtesan is depicted as the object of the assumed male gaze, but she also returns the gaze by looking directly at the viewer. She is poignantly contrasted with the fully clothed body of her Black servant, a representative of racialized and colonized women in the western tradition who appear as the animalistic, primitive other threatening the white woman’s assumed purity. Black feminist art theorist Charmaine Nelson argues that because a naked Olympia looks straight back at the viewer with an unashamed, steady, even confrontational gaze, Manet was trying to subvert conventionalized assumptions of the subjugating gaze, raising questions of who should do the looking and who, if anyone, should be considered impure: the white woman or her Black maid. Either way, the painting caused a scandal amongst the French viewing public at the time because it challenged the white male and colonial gazes.

Polish artist Katarzyna Kozyra’s “Olympia” (1996) exposes the medical gaze, thus debunking the intrusive, insensitive stares encountered by women who are considered abject or pathologized. The reclining nude on a stretcher here features as the object of a cancer specialist and, rather than forming the object of erotic desire, she represents illness and death as well as the unequal power relationships between the doctor and the sexually female patient whose illness has deprived her most of her stereotypical sexual signifiers (hair and breasts). Kozyra’s work thus critiques the medical and, by extension, the able-bodied gaze, directed at any perceived female monstrosities, including pregnancy (see Braidotti; Rice).

In her series, “Not Manet’s Type” (1997), African American photographer Carrie Mae Weems explores looking relations between white male artists and Black women. Her work critically exposes the way in which the paintings of white male art “masters” have traditionally defined and conceptually limited beauty as a Western ideal of whiteness. Weems creates “staged” representations that challenge the exclusion of images of Black girls and women from art and popular media. She is interested in power relations between subjects and viewers, how they are constructed through images, and how images may be leveraged to contest those power relationships (Bey).

Other gazes that artists and popular media have engaged with include, for example the thin-bodied gaze (Haley Morris-Cafiero), the cisgendered gaze, the settler-colonial gaze, and the postfeminist gaze between women. The latter, which we typically encounter in women’s magazine’s cover images, can be one of the most insidious and elusive ones because of its ambivalence, fluidity, and complexity. As postfeminist media scholar Rosalind Gill (“From Sexual Objectification” 104) argues, the shift from an “external, male judging gaze” to an internal “self policing” gaze may represent deeper manipulation, since it invites female audiences to become more adept at scrutinizing their own and other women’s images (see Rice; Riley, Evans, and Mackiewicz).

In this paper, we go a step further and challenge the fact that, in all examples of scopophilic visual culture discussed so far, the object of the gaze remains at a mediated distance. The female body consistently figures as an object of imagined penetration yet manifest separation. In body-themed works of electronic literature (and other forms of digital-interactive narrative), by contrast, this mediated distance is minimized or seemingly erased by a material, symbolically permeable interface between the body of the voyeur and the body on screen (Rice, LaMarre, Changfoot, and Douglas). These medium-specific affordances allow e-lit artists to hold the voyeur unaccountable for objectifying the target they are manipulating rather than simply observing. Whilst there are manifold ways in which e-lit has critically engaged with scopophilia, perhaps the most pertinent of these responses is what we call the “ergodic gaze.”

In Annie Abrahams’ agency art e-poem, “Ne me touchez pas / Don’t touch me”, and in geniwate and Deena Larsen’s hypermedia fiction, The Princess Murderer, the user-activated, ergodic cursor physically enacts the gaze of the beholder. With every touch or click, respectively, these works materialize the reader-player’s insatiable appetite to control the screen and all that it embodies. Reading “Ne me touchez pas” involves mousing-over the body of a reclining, scantily dressed woman who is turned away from the camera and buries her head in her pillows to avoid the viewer’s gaze. Reader-players of The Princess Murderer, by contrast, activate a murder or rape of a fairy tale princess in Bluebeard’s castle with every click of the mouse. Simultaneously, every click triggers a high-pitched sigh, indexing a woman’s suffering.

The cursor, which Marie-Laure Ryan terms “the representation of the reader’s virtual body in the virtual world” (122), thus represents an “augmented me” (Keogh 3). The augmented me “is ‘you’ and ‘You,’ as the narrator distinguishes us while also drawing us together” and making us “feel some liminal and flickering sense of presence through the screen” (Keogh 3). This idea of “embodiment … distributed across both sides of the glass” (Keogh 5) is a phenomenological concept of presence that reflects the mutual incorporation of player and game, of reader and digital-born text. And yet, whilst, in most videogames, it would probably be correct to say, with Keogh, that “as we touch the videogame, it touches us back” (4), this is a far cry from the truth in “Ne me touchez pas.” The work poignantly implements the despair of the faceless woman’s body on screen that we, as player-readers, keep poking mindlessly, without obtaining the expected cybernetic feedback. She does not want to touch us back: all she wants is to break free from the constraints of the ergodic gaze, a physically and forcefully enacted gaze which, in the meta-Perrauldian, pornographic world of The Princess Murderer, graphically click-rapes, click-murders, and click-rebreeds its objectified victims.

A verbally finessed version of the ergodic gaze can be found in Emily Short’s Galatea, in which the protagonistic “you” is forced to deploy actions upon Galatea - quite literally chiseling away at her embodied self, via directive, transitive command line speech acts. These acts perform the ergodic gaze linguistically, by depriving Galatea of any communicative agency - despite her periodical complaints about this uneven power relationship - and reducing her artificial intelligence to responsive submissiveness and, ultimately, emotional capitulation, even in the “happiest” of all possible endings.

4.Writing Women’s Bodies in E-literature

E-lit has engaged with women’s bodies in a variety of ways that cannot be reduced to the ergodic gaze. A second, alternative approach is for example the theme of becoming women via social inscription (inspired by Elizabeth Grosz; see Rice). It comes to the fore in Juliet Davis’ dress-up e-poem, “Pieces of Herself,” where women’s “docile bodies” (Foucault) are quite literally inscribed by interactive icons of domesticity. This docility is subverted in Caitlin Fisher’s hypermedia fiction, These Waves of Girls, which explores queer femininity and lesbian sexuality in young women subjugated by heteronormative society.

A third and probably most canonical way of writing women’s bodies in e-lit is via the idea of the fragment that eludes the reader-player as it constantly deconstructs and reconstructs itself in absentia. The metaphors of quilting, weaving, sewing and patching are dominant in Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork Girl and Christine Wilks’ interactive Flash memoir, Fitting the Pattern. The former has frequently been called upon as the perhaps most fitting allegory of poststructuralist thought in digital space as the hypertextual, female monster presents a compelling, cyberfeminist response to the phallocentric ur-story. Whilst the loving relationship between the fictional Shelley and her female monster seems to pose a valid alternative to the hateful relationship between Frankenstein and his monster, Shelley’s monster remains fluid and intangible as she undergoes a process of inevitable decomposition and fragmentation. In Fitting the Pattern, by contrast, Wilks’ reader-player can choose from a range of dressmaking tools to sew together autobiographical sketches, thus allowing the reader to construe elements of Wilks’ younger self from ludic-readerly interaction. Those sketches, which appear in lexias on pieces of cloth, reveal the protagonist’s exposure to the restrictive body ideals of her time, culture and class, as well as the overpowering role of her mother in trying to make her “fit” those ideals. Yet again, Wilks’ former self appears in absentia and fragmentation, thus giving rise to questions of self-denial and conflicted identity.

The fragments-in-absentia theme is strongly informed by second wave feminist voices (most famously Hélène Cixous and Luce Irigaray) that, in the mid-1970s, called for new, anti-phallocentric forms of writing. Cixous argued that the truths we know and tend to subscribe to are man-made and man-biased. In “The Laugh of the Medusa” she urges women to reclaim their bodies and, by extension, their desires and identities through writing. The challenge but also potentially liberating implication of écriture feminine is, according to Cixous, that women’s writing as an intervention but simultaneously as a fleeting concept cannot be reduced to an essence – and this is what makes it so relevant for fluid, dynamic, and playful digital as well as post-digital, medium-critical re-encodings.

In response to Cixous’ call, di Rosario highlights the work of Maria Mencia (e.g. “Birds Singing Other Birds Songs”) as powerful attempts at developing “a new poetic form of language” (274). This new language oscillates elusively between human and animal and manifests as a perpetual “play with letters, sounds, and forms” (di Rosario 274) that blend and mould while reading. Di Rosario further suggests that post-digital écriture feminine may involve writing new spaces, which break their own constraints for poetic writing. This is the case, for instance, in Christine Wilks’ and Andy Campbell’s Unity-based, immersive 3D fiction Inkubus, where the reader-player navigates the interior of a human body. Not unlike in a first person shooter, the player-character can hit inimical units. Yet these units of opposition are here fragments of appearance-based cyberbullying, which can be shot with a fireball, thus re-appropriating and detourning phallic mechanics.

5.Writing New “Bodies”

Having mapped out the field of creative practice in body-themed e-literature, we shall now explore how writing and reading e-lit (and digital fiction in particular) might be explored as a body image intervention as a case study in applied e-lit studies. The “Writing New Bodies” project employs participant research to start thinking about how a research-creation project might help young woman-identified and gender non-conforming individuals open up new ways of envisioning their bodies, to write new worlds in which they feel at home in their bodies, and to explore spaces for creating and experiencing these new, embodied worlds, individually and collectively. Thus, it is more appropriate to talk about writing new “worlds for bodies to feel at home in” than new “bodies” themselves - hence the quotes in the heading for this section. As theoretical backdrop, we adopt a xenofeminism-inspired vision of difference as a combination of anti-binarist super-diversity and peripheral centripetality, a vision that embraces intersectionality as a matrix that normalizes queerness, complexity, métissage (Donald), and fluidity.

Funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, “Writing New Bodies” aims to develop a digital fiction for a new form of contemporary, digital-born bibliotherapy. In following the principles of critical community co-design and feminist participatory action research (FPAR; Gustafson, Parsons, and Gillingham), our participants are both designers and beneficiaries of the artwork that will be created, and of the processes that lead to its creation. The project is run out of the University of Alberta with input from critical psychologists and social scientists as well as body image, social justice, and bibliotherapy experts from the Universities of Guelph, Massey (NZ), Laurentian, and Trinity College (CT), and in collaboration with feminist digital fiction artist, Christine Wilks.

Our research is centered around the following research questions:

- How might our target population of young women-identified and gender nonconforming individuals ages eighteen to twenty-five contribute meaningfully to the design and development of a new digital fiction for body image bibliotherapy?

- How might the co-design process help participants reflect on body image concerns and build greater levels of resilience (approached as socially and relationally produced concept) to sociocultural pressures that cause them to be dissatisfied with their bodies, and

- What interactive, representational, and narrative designs and technologies might benefit bibliotherapists and our target population?

Methodologically, we are using a combination of Feminist Participatory Action Research and Critical Community Co-Design. FPAR is a participatory and action-oriented conceptual and methodological framework that centers gender diverse and women’s experiences both theoretically and practically, aiming to empower woman-identified individuals in a variety of ways. It enables a critical understanding of women’s multiple perspectives and works toward inclusion and social change through participatory processes while exposing researchers’ own biases and assumptions. Importantly, researchers and participants learn from each other through iterations of critical reflection and re-design. This process blends well with methods of critical co-design, where users engage in iterative cycles of critical design, reflection, and evaluation (including beta-testing).

5.1 Workshop Set-up and Data

In April and May 2019 we held four workshops in three Canadian locations, with a total of 21 participants. They engaged in a range of communicative activities, such as reflective dialog, and free, autonarrative writing (sometimes using third person to talk about themselves at a narrative distance). They played digital body fictions made by Christine Wilks, as well as a range of Twine fictions, to get a feel for the software and its storytelling options. They also wrote their own Twine stories as a form of interventionist self-disclosure and as a hypertextual exploration of options they may not usually consciously consider as part of imagining their bodies and the decisions they make about their embodied lives (for a proof-of-concept study, see Ensslin, Skains, Riley, Haran, Mackiewicz, and Halliwell). What turned out to be a key element of the workshops was the fact that Christine Wilks was present throughout and engaged with participants as artist, co-facilitator, and software instructor. Her experience of working with our participants has proven to be vital for her ability to develop a co-designed digital fiction.

We recruited participants from a range of gender and sexual identifications, from different ethnic backgrounds, as well as people with physical and psychological disabilities (which we call bodymind differences). Most of them had body image concerns, and/or a history of disordered eating. Only two of them identified as plus-sized (using terms such as curvy, thick, “over”weight or fat), but in many stories and discussions it became clear that anti-fat attitudes and more precisely, fatmisia (fat hatred) (Rinaldi, Rice, Kotow, and Lind), are dominant in their bodily experiences of themselves and others.

Four types of data emerged from the research: audio-recordings of the workshops, fieldnotes, the stories participants wrote on paper and online, and participant feedback. The content and form of participant stories directly informed the design brief, compiled from our qualitative data analysis and coding in MAXQDA. The design brief was compiled collaboratively with input from the whole research team, Wilks’ own reflections and creative ideas, and professional feedback from bibliotherapy experts.

5.2.Results

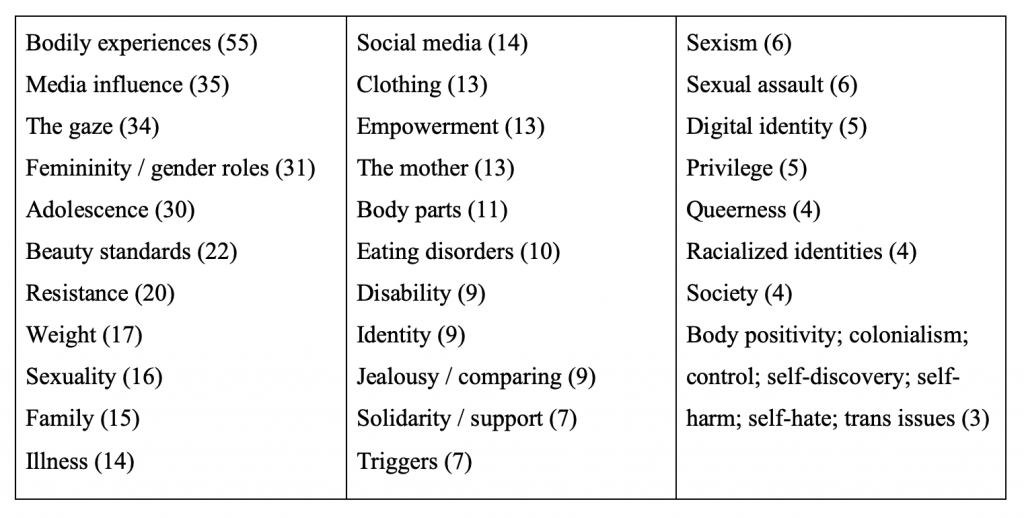

Predominant body image themes that came up in participant discussions are listed in Table 1. Bodily experiences are as diverse as participants themselves, but some frequent themes were for example the importance of finding moments of peace and comfort with one’s body; the pervasiveness of body hate related to the primacy of appearances, and feelings of body shame. But there were also positive experiences to do with moving one’s body, and the immediate in-sync relationship children tend to have with their bodies before they enter adolescence (Rice).

Further key themes include, for example, media influences, familial influences (with “the mother” singled out and listed separately), binary, heteronormative gender roles that are hard to break out of, beauty standards, weight, sexuality, but also ways of empowering oneself, of developing resistance and (relational and contextual) resilience to social pressures, for instance by taking photos of one’s own body and loving it, or even sharing them on Instagram despite maternal admonition.

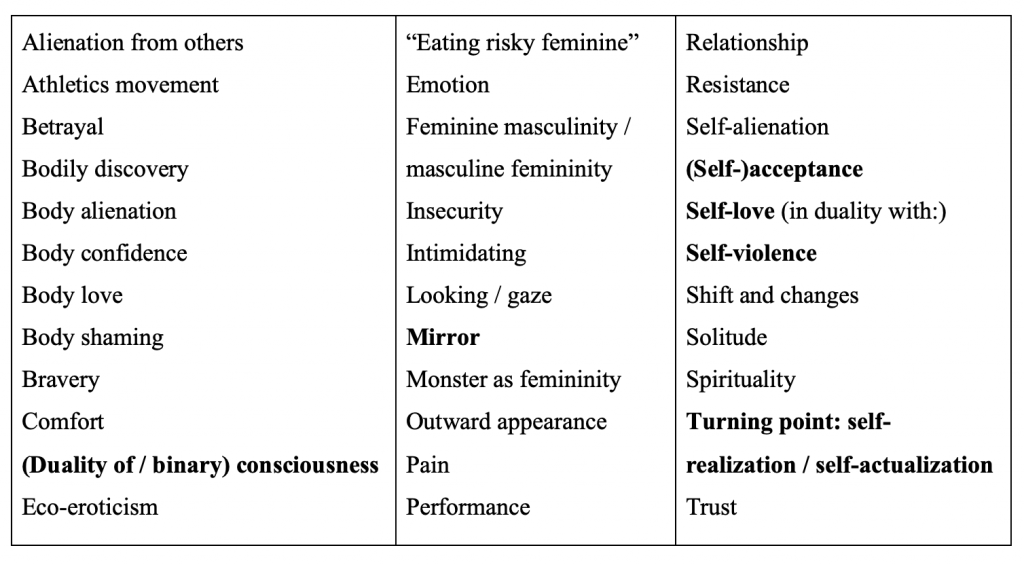

These themes, which arose in participant discussions, have to be seen in dialog with those that the participants identified explicitly while reflecting about the stories they wrote during the workshops. Amongst the most frequently mentioned, self-identified themes (see Table 2, bolded items) were the conflict arising from the duality of consciousness and the difficulty of breaking out of and resisting socially inscribed binary thought. The mirror - which, incidentally, is often used as an exposure tool in body image counselling (Well) - came up repeatedly as a prevailing symbol of body image and self-reflection, and there was a complex array of partially conflicting feelings about one’s body, including acceptance of one’s own and other people’s bodies, and self-love vs. self-violence (see Rice). Interestingly, most stories featured some kind of turning point: a point of self-realization or self-actualization along the lines that they had never before ventured that far into their embodied memories and that this engagement with non-activated cognitive material might open up new ways of appreciating their embodied lives and biographies.

As co-facilitator, Wilks involved the groups in a series of creative exercises, which generated ideas for narrative design and technological implementation. For example, most participants seemed to agree that a visually represented avatar may create strong bias and therefore it could be beneficial to use an abstraction to allow reader-player self-reflection. They also seemed to prefer the idea of voices over actual characters. For instance, the role of the protagonist could be represented by a voice of recovery, or a fighting voice. Antagonistic voices, in turn, might represent alienation from oneself and one’s peer groups. They might represent what we escape from; or they might represent a sick, self-critical, or self-violent voice. Other voices that might feature are those of the collective mother, or the comparative voice, which constantly sets us apart from other bodies, typically in self-deprecating, or biased ways.

For story world and narrative design, participants suggested engagement with the cyclical nature of all bodily things and all narratives, incidentally, including the constant oscillation between freedom and restriction, between self-hatred, compassion and love, between indulgence and punishment. This pattern aligns with Riley, Evans, and Mackiewicz’ description of the postfeminist gaze as an oscillation between self/other and subject/object. Stories in the envisaged digital fiction universe might suggest ways of breaking out of these looping thoughts and behaviors. A particularly thought-provoking suggestion was the idea of exploring the non-binary gaze and what kinds of looking relations it might entail. Finally, some participants mentioned the importance of being able to share and read each other’s stories for empathy and support instead of jealousy and dissatisfaction. For bibliotherapy in particular, it will be important to offer positive options and solutions. After all, the potential for inspiring hope and comfort is important in bibliotherapy materials and practices (Bruneau and Pehrsson).

Preferred technologies, according to the participants, are mobile ones: smartphones and tablets. Yet they also mentioned the primacy of image-taking and manipulation, and they highlighted the importance of transformative, accessible, intuitive technologies, such as Twine (rather than Unity) and Instagram (rather than Facebook).

The main goals of the WNB workshops were co-creative rather than a therapeutic in nature. Nonetheless, we wanted to know whether anything had shifted for our participants, about four weeks after the workshops. Individual responses to our online questionnaire mentioned, for example, the realization that body insecurities were due to only a small number of particular events (P1); that “women of all sizes have body issues” (P2), and that they 1 felt a greater sense of “kinship with women instead of an undercurrent of jealousy or misunderstanding” (P2); P3 mentioned that the workshop made them realize that recovery can be a creative and less linear process than commonly assumed; and P4 said the experience of engaging with their own and other participants’ Twine stories made them “more aware of the decision making [they engage] in with regards to [their] body image” and “more conscious about how many choices [they make] daily in how [they feel] about and [treat their] body.” Finally, P5 reported that they learnt more about them self: “about the hidden/repressed body ‘moments’ and awarenesses which [she] did not fully address or acknowledge in the past but really dictate how [she] moves through the world.” This qualitative data offers preliminary support for the thesis that FPAR as a co-creation method can be beneficial for participants in body image interventions, especially with respect to awareness-raising about one’s own embodied realities and their historical embeddedness, and in terms of sharing body image concerns spiritually and through different channels of argumentative and narrative, online and offline, linear and multilinear communication.

6.Conclusion

Applied electronic literature research of the kind we introduced in this paper is still in its infancy. To do it, we had to create a collaborative, transdisciplinary methodology through which we have (1) identified ways in which theories and practices of electronic literature and body image can be brought together; (2) shown how, in a participatory action research project, researchers and participants can explore how digital stories can be leveraged to widen body image narratives and to open up spaces for women-identified and gender non-conforming individuals to be able to explore and review their body image challenges; and (3) identified some of the ways in which our target population might re-story these challenges (see Table 2).

Applied e-lit is thus a collaborative, transdisciplinary venture that directly engages its target audiences in a process of critical reflection, self-expression, and community design. It is designed as an intervention that will benefit its co-creative audiences and it builds these audiences into the research process as an integral component from start to finish. It therefore poses a steep and vital learning curve for all involved: researchers, artists, participants and expert advisors. It is committed to social justice, and it can bring e-literature practice and scholarship into greater dialog with new, disenfranchised or otherwise marginalized user groups, thus centering peripheries on multiple, co-productive levels. In this spirit, we would like to close by acknowledging the contribution of all our anonymized participants. Without them, this project would not have materialized and advanced to this stage.

This article has reported on phase one of a two-phase project, where we have focused on bridging e-literature and body image theory and practice, and on conducting participant research for the WNB design brief. Phase two will flesh out and implement our analytical findings by designing and creating the digital fiction, testing, and launching it to a broad audience of readers, therapists and facilitators.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada for supporting this research with an Insight Grant (SSHRC IG 435-2018-1036). Further thanks goes to Annie Abrahams and Stephanie Strickland for their useful comments on earlier drafts of this article.

References

Aarseth, Espen. Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins UP, 1997.

Angel, Maria, and Anna Gibbs.”At the Speed of Light: Cyberfeminism, Xenofeminism and the Digital Ecology of Bodies.” #WomenTechLit, edited by Maria Mencia, Morgantown, WV: WVU Press, 2017, pp. 41-54.

Bell, Alice. “Interactional Metalepsis and Unnatural Narratology.” Narrative, vol. 24, no. 3, 2016, pp. 294-310.

Bell, Alice, Astrid Ensslin, Isabelle van der Bom, and Jen Smith. “Immersion in Digital Fiction: A Cognitive, Empirical Approach.” International Journal of Literary Linguistics, vol. 7, no. 1, 2018, https://journals.linguistik.de/ijll/index.php/ijll/article/view/105.

Berger, John. Ways of Seeing. London: BBC, 1972.

Berlant, Lauren. Cruel Optimism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011.

Bey, Dawoud. “An Interview with Carrie Mae Weems by Dawoud Bey.” BOMB Magazine, July 10th, 2019,http://magazine.art21.org/2009/07/10/an-interview-with-carrie-mae-weems-by-dawoud-bey/#.XYj7-yhKhPY.

Braidotti, Rosi. “Mothers, Monsters and Machines.” Writing on the Body: Female Embodiment and Feminist Theory, edited by Katie Conboy, Nadia Medina, and Sarah Stanbury, New York: Columbia University Press, 1997, pp. 59-79.

Brodesco, Alberto and Federico Giordano. “The Border Within: The Human Body in Contemporary Media.” Body Images in the Post-Cinematic Scenario: The Digitization of Bodies, edited by Alberto Brodesco and Federico Giordano, United States: Mimesis International, 2017, pp. 9-17.

Bruneau, Laura and Dale-Elizabeth Pehrsson. “The Process of Therapeutic Reading: Opening Doors for Counselor Development.” Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, vol. 9, no. 3, 2014, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/15401383.2014.892864?mobileUi=0.

Chandler, Eliza and Carla Rice. “Alterity in/of Happiness: Reflecting on the Radical Possibilities of Unruly Bodies.” Health, Culture and Society, vol. 5, no. 1, 2013, 230-248.

Chatzichristodoulou, Maria. “Karen by Blast Theory: Leaking Privacy.” Digital Bodies: Creativity and Technology in the Arts and Humanities, edited by Susan Broadhurst and Sara Price, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017, pp. 65-78.

Cixous, Hélène. “The Laugh of the Medusa.” trans. Keith and Paula Cohen. Signs, vol.1, no. 4, 1976, pp. 875-893.

Diemer, Elizabeth W. , Jaclyn M. White Hughto, Allegra R. Gordon, Carly Guss, S. Bryn Austin, and Sari L. Reisner. “Beyond the Binary: Differences in Eating Disorder Prevalence by Gender Identity in a Transgender Sample.” Transgender Health, vol. 3, no. 1, 2018. Online First, http://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2017.0043

di Rosario, Giovanna. “Gender as Patterns: Unfixed Forms in Electronic Poetry.” #WomenTechLit, edited by Maria Mencia, Morgantown, WV: WVU Press, 2017, pp. 41-54.

Dohnt, Hayley K. and Marika Tiggemann. “Body Image Concerns in Young Girls: The Role of Peers and Media Prior to Adolescence.” Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 2006, Online First, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs10964-005-9020-7#citeas.

Donald, Dwayne. “Indigenous Métissage: a Decolonizing Research Sensibility,” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, vol. 25, no. 5, 2012, pp. 535-555.

Ensslin, Astrid. Canonizing Hypertext: Explorations and Constructions. London: Bloomsbury, 2007.

Ensslin, Astrid, Alice Bell, R. Lyle Skains, and Isabelle van der Bom. “Immersion, Digital Fiction, and the Switchboard Metaphor.” Participations: Journal of Audience and Reception Studies, vol. 16, no. 1, 2019, https://www.participations.org/Volume%2016/Issue%201/16.pdf

Ensslin, Astrid, Carla Rice, Sarah Riley, Aly Bailey, Hannah Fowlie, Lauren Munro, Megan Perram, and Christine Wilks. Writing New Bodies. Project website, 2019, https://sites.google.com/ualberta.ca/writingnewbodies/home.

Ensslin, Astrid, R. Lyle Skains, Sarah Riley, Joan Haran, Alison Mackiewicz, and Emma Halliwell. “Exploring Digital Fiction as a Tool for Teenage Body Image Bibliotherapy.” Digital Creativity, vol. 27, 2016, Online First: https://doi.org/10.1080/14626268.2016.1210646.

Fisher, Caitlin. These Waves of Girls. 2001, http://www.yorku.ca/caitlin/waves/.

Flores, Leonardo. “Third Generation Electronic Literature.” electronic book review, 7 April 2019. http://electronicbookreview.com/essay/third-generation-electronic-literature/.

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage Books, 1995.

Gardner, Colin. “Meta-interpretation and Hypertext Fiction: A Critical Response.” Computers and the Humanities, vol.37, 2003, pp. 33-56.

Gill, Rosalind. “From Sexual Objectification to Sexual Subjectification: The Resexualization of Women’s Bodies in the Media.” Feminist Media Studies, vol. 3, no. 1, 2003, pp. 99-106.

Gill, Rosalind. “Postfeminist Media Culture: Elements of a Sensibility.” European Journal of Cultural Studies, 2007, Online First: https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549407075898.

Grosz, Elizabeth. Volatile Bodies. Bloomington, IN: University of Indiana Press, 1994.

Grogan, Sarah. Body Image: Understanding Body Dissatisfaction in Men, Women and Children. 2nd ed. London: Routledge, 2008.

Gustafson, Diana L., Janice E. Parsons, and Brenda Gillingham. “Writing to Transgress: Knowledge Production in Feminist Participatory Action Research.” Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 20(2), 2019, pp. 1-25

Hayles, N. Katherine. “Deeper into the Machine: The Future of Electronic Literature.” Electronic Literature: State of the Arts Symposium. UCLA. April 5, 2002. https://elmcip.net/critical-writing/deeper-machine-future-electronic-literature.

Hayles, N. Katherine. Electronic Literature: New Horizons for the Literary. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2008.

Keogh, Brendan. A Play of Bodies: How We Perceive Videogames. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2018.

LaMarre, Andrea, Jen Rinaldi, and Carla Rice. “Tracing Fatness through the Eating Disorder Assemblage.” Thickening Fat: Fat Studies, Intersectionality and Social Justice, edited by Jen Rinaldi, Carla Rice, and May Friedman, New York: Routledge, 2020, pp. 64-76.

Mangen, Anne and Adriaan van der Weel. “Why Don’t We Read Hypertext Novels?.” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media, vol.23, no. 2, 2017, pp. 166-181.

_ _Manovich, Lev. “Postmedia Aesthetics.” Transmedia Frictions: The Digital, the Arts, and the Humanities, edited by Marsha Kinder and Tara McPherson, Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2014, pp. 34-44.

Miall, David S. and Teresa Dobson. “Reading Hypertext and the Experience of Literature.” Journal of Digital Information, vol. 2, no. 1, 2001, https://journals.tdl.org/jodi/index.php/jodi/article/view/35/37 /.

Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Screen, vol. 16, no. 3, 1975, pp. 6-18.

Nelson, Charmaine. Representing the Black Female Subject in Western Art. New York: Routledge, 2010.

Parisi, Luciana. Abstract Sex: Philosophy, Biotechnology and the Mutations of Desire. London: Continuum, 2004.

Pope, James. “A Future for Hypertext Fiction.” Convergence, vol.12, no. 4, 2006, pp. 447-465.

Pope, James. “Where Do We Go From Here? Readers’ Responses to Interactive Fiction: Narrative Structures, Reading Pleasure and the Impact of Interface Design.” Convergence, vol. 16, no. 1, 2010, pp. 75-94.

Rice, Carla. Becoming Women: The Embodied Self in Image Culture. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2014.

Rice, Carla, Eliza Chandler, Kirsty Liddiard, Jen Rinaldi, and Elisabeth Harrison. “Pedagogical possibilities for unruly bodies.” Gender and Education vol. 30, no. 5, 2018, pp. 663-682.

Rice, Carla, Andrea LaMarre, Nadine Changfoot, and Patty Douglas. “Making spaces: Multimedia storytelling as reflexive, creative praxis.” Qualitative Research in Psychology, 2018, pp. 1-18.

Riley, Sarah, Adrianne Evans, and Alison Mackiewicz. “It’s just between girls: Negotiating the postfeminist gaze in women’s ‘looking talk’.” Feminism and Psychology, vol. 26, no. 1, 2016, pp. 94-113.

Riley, Sarah, Adrianne Evans, and Martine Robson. Postfeminism and Health. London: Routledge, 2018.

Riley, Sarah, Adrienne Evans, Sinikka Elliott, Carla Rice, and Jeanne Marecek. “A critical review of postfeminist sensibility.” Social and Personality Psychology Compass vol. 11, no. 12 2017: e12367.

Rinaldi, Jen, Carla Rice, Crystal Kotow, and Emma Lind. “Mapping the circulation of fat hatred.” Fat Studies, 2019, 1-14.

Rustad, Hans Kristian. Digital litteratur. Oslo: Cappelem Damm akademisk, 2012.

Ryan, Marie-Laure. Avatars of Story. Minnesota MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2006.

Skains, R. Lyle. “Teaching Digital Fiction: Integrating Experimental Writing and Current Technologies.” Palgrave Communications 5:13, 2019, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41599-019-0223-z

The Renfrew Center Foundation for Eating Disorders. “Eating Disorders 101 Guide: A Summary of Issues, Statistics and Resources,” 2003, www.renfrew.org.

Tisseli, Eugenio. “La comunidad extendida,” horizontal, Dec. 13, 2017, https://horizontal.mx/la-comunidad-extendida/.

Watson, Ryan J., Jaimie F. Veale, and Elizabeth M. Saewyc. “Disordered Eating Behaviors Among Transgender Youth: Probability profiles from risk and protective factors. International Journal of Eating Disorders 2017; 50 :515–522.

Well, Tara. “Dealing With Body Image Issues: How Confronting Your Own Image Can Reduce Self-criticism.” Psychology Today, April 16, 2018, https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/the-clarity/201804/dealing-body-image-issues.

Footnotes

-

Gender-inclusive pronouns have been chosen deliberately in this section to represent anonymized participant speech. ↩

Cite this article

Ensslin, Astrid and Carla Rice, Sarah Riley, Christine Wilks, Megan Perram, Hannah Fowlie, Lauren Munro and K. Alysse Bailey. ""These Waves ...:" Writing New Bodies for Applied E-literature Studies" Electronic Book Review, 5 April 2020, https://doi.org/10.7273/c26p-0t17