Digital Narrative and Experience of Time

Through the examples of three types of digital stories, including an interactive narrative for the smartphone based on notifications, a web narrative based on a real time data flow, and the widely used social media feature of stories, Bouchardon and Fülöp explore the relationship between the digital, temporality, and narrative. They ask, "what new narrative forms, or even new concepts of narrative do these new temporal experiences provided by digital technology offer to us?"

It is often said that our relationship with time has changed in recent years. New Management strategies mean that employees feel themselves subjected to ever increasing urgency and stress. FOMO, the fear of missing out is a phenomenon inherently linked to the digital environment and its constant flow of information. The Covid-19 crisis has no doubt accentuated this tendency, with its injunction to stay connected and respond immediately to digital notifications and solicitations on a 24/7 basis.

According to Paul Ricoeur (1984), “Time becomes human to the extent that it is articulated through a narrative mode, and narrative attains its full meaning when it becomes a condition of temporal existence.” From this perspective, narrative is our principal tool for situating ourselves in time ― and for making sense of time within ourselves. The digital, on the other hand, may be characterized as “a tool for the phenomenal deconstruction of temporality” (Bachimont 2010). This is reflected in its two main tendencies: that of real time calculation, conveying the impression of immediacy, and that of universality of access, conveying the impression of availability. The digital, thanks to its availability and its immediacy, thus leads to constant present, without any impression of the passage of time (Bachimont, 2014).

What happens then when the digital and narrative are combined, despite this inherent tension? What happens when we exploit the capabilities of “programmable media” (Cayley 2018), which for Bachimont are essentially detemporalizing, to tell a story, traditionally understood as being structured by an internal temporality and linked to an external one? From this perspective, the term digital narrative appears oxymoronic.

Digital narratives do nevertheless exist now in multiple types and forms. If the digital medium is principally a medium for detemporalization, it nonetheless makes it possible to perform time. It enables time to be acted out, or to play a role in a fictional work thanks to the interactive dimension it offers to the user. If we are to compare the different ways of staging time depending on the medium, we can observe that the inherently time-based audiovisual media are by definition prescriptive with respect to their temporality ― the length of a film coincides with the viewer’s stream of consciousness (Stiegler, 1998), even if media for individual use allow for interruptions, rewinding, fast forwarding or acceleration, modifying the original temporality inscribed in a fictional work. The printed text is inversely not very prescriptive; the reader acts out his/her own reading time, between interruptions and skimming. The digital, in its capacity as a metamedium (Manovich 2001), is capable of reproducing the characteristics of all previous types of media without their materiality and can act both ways. It can also offer other dimensions thanks to its inherent interactivity and to its being connected to a network and external resources, which allows it to draw on and manipulate temporality.

We speak of acting out and performing. Jerome Fletcher (2012) proposes that performance, considered in its relation to performativity, should be taken in its broadest sense in the field of digital literature. Thus performance could refer to various dimensions of digital texts, including

interactivity; the performative gesture of the hand and fingers (digital text) on the interface; the performativity of language itself on the screen; social performance, or how digital texts “perform” us; the performance of codes and scripting; and the performance of the machine itself, i.e., what does an engineer mean when s/he talks about performance?

Performance means that a process is underway; it is an event rather than an object. Ian Bogost’s (2007) concept of “procedural representation” further highlights the uniqueness of digital works in relation to performativity:

[procedural representation] explains processes with other processes. Procedural representation is a form of symbolic expression that uses process rather than language. […] Procedural representation itself requires inscription in a medium that actually enacts processes rather than merely describes them.

The digital narrative, insofar as it constitutes an event and process performed by the machine and by the reader, may (re-)introduce temporality, a temporality that intertwines the activity of the computer with that of the reader-player-user. This (inter)active manner of living a temporal experience must be distinguished from the experience of time constructed by all narratives according to Ricoeur. We have on one hand the temporal experience brought into existence and formulated through narrative by its very essence, according to its traditional classification as discourse establishing a chronology and causality and on the other hand, the temporal experience performed by the reader-user, based on a process taking place on a timescale with a varying degree of manipulability, within the frame and the limits imposed by the software.

The question arises then as to what kind of temporal experiences are constructed by digital narratives and how are they constructed? Reciprocally, what new narrative forms, or even new concepts of narrative do these new temporal experiences provided by digital technology offer to us? In order to analyse the diverging potentialities of the relationship between the digital, temporality and narrative, we will focus on three very different types of digital stories, including two artistic works and the widely used social media feature of stories. Each example explores the notion of temporality and the use of time in the digital “narrative” from a different angle. First, we look at the interaction between the real time of the reader and his/her reading with narrative time and so with the fictional work, then we examine the use of the diegetic time determined by the data flow, which becomes the temporal axis of a work we present, and finally we analyse the implications of the temporality imposed by the story feature on social media platforms, presented as a constitutive aspect of the story, and which the user’s content needs to adapt to.

1. Narrative games for the smartphone: smartfictions built around notifications

Narrative can help to (re)construct into a coherent whole the incoherence of the information flow, particularly manifest through smartphone notifications. Our first example looks at how certain digital narratives stage this flow of what is happening in order to render it coherent.

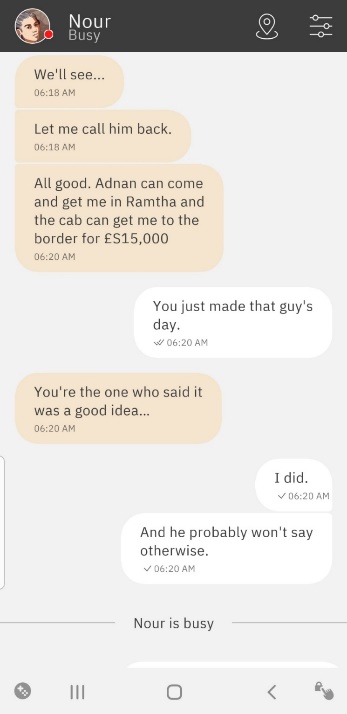

On mobile application distribution platforms (Google Play and App Store) one can find more and more interactive narratives for smartphones, or smartfictions (Picard, 2021). These fictions rely on ordinary daily practices on a smartphone, realtime chats, for instance, but also notifications. Bury me, my Love (Enterre-moi, mon amour, 2017) is a narrative game inspired by the WhatsApp witness account of a young Syrian woman migrating to Germany published by the journal Le Monde in 2016 under the title The Diary of a Migrant. In the interactive fiction, the reader incarnates the character of Majd, the husband of Nour, the Syrian woman attempting to reach Europe. The reader exchanges messages with Nour via an instant messaging platform. The duration of the journey between Syria and Europe is not pre-determined. It can take anything between a few days and a few weeks.

The interaction between the chronology and the temporality of events becomes entwined with the play between cartography and spatiality. The reader can follow Nour’s progression via a GPS tracker in the top right corner of the instant messaging screen, and so can visualize the character’s progression in real time on a map. This temporality is also an indication of the reader’s progression through the narrative. The closer Nour gets to a European country, the closer the reader is to the end of his/her reading experience. The tracker is therefore a spatial and temporal indication of both the character’s progression and that of the reader in his/her reading process.

As the reader travels along the various pathways (there are 19 different possible endings), a digital counter indicates the number of days that have passed. The border may be temporarily closed, or Nour might have scheduled a meeting with someone who doesn’t turn up on time. In such cases, is it better to wait, or to reconsider your plans?

Your communications will take place in pseudo real time ―if Nour must accomplish an action which is supposed to take her several hours, you will not be able to contact her during this time lapse. When she returns, a notification will inform you that she is again available ―and that she might need you.

The piece plays with temporality through the intrusion of the reader’s real time – which is then also that of the fictional character. The relationship to the reading time is altered, due to the intrusion of notifications: when the user receives a notification from Nour, amongst their other, real-life notifications, they are incited to dive back into the story to dialogue with the character. From a phenomenological perspective, we can consider that there is an interruption caused by the injunction behind the notification. In the same way as locative narratives play on the boundaries between fictional space and the reader’s real space, inciting him/her to physically move to a specified place to make the narrative progress, narratives built around notifications play on the boundaries between fictional time and the reader’s real time. Through the notifications, smartfictions thus create the impression of a co-presence. As readers of, or actors in a smartfiction, when we make a choice, our actions in a way render a fictional character present in our own reality. Moreover, this notion of presence is further reinforced when we respond to a character’s solicitation via a notification. In this way we invite the other’s temporality (as well as that of the fiction) to interact with our own. The temporality of the fictional character (and of events) coincides with the reader’s temporality via the notifications, so that they interiorize the duration of the story.

This interplay relies on the fact that the smartphone is the device which we now use for an increasing portion of our communications. If this characteristic lends a reality effect to a fictional narrative, we also realize, due to the fiction’s notifications that have a blurring effect on our own reality, that the smartphone is itself in some ways a medium of derealization: it can create a fictional layer which is external to the real world. Thanks to such fictional works, we come to understand that the smartphone has already become a medium for fiction (and for narration), bringing a new relationship with temporality as well as with fiction and narrative.

2. Narratives built around real time data flows

If the digital manifests itself through an increasing overflow of data, it produces this data flow through a calculatory logic, whereby time is no longer present as a horizon of expectation and anticipation, as we are dealing with results based on the world understood as input data, rather than occurrences (Bachimont, 2021). Is it possible to re-establish a temporal experience, notably the power of expectation, based on these calculated results?

In The Language of New Media (2001), Lev Manovich coins the term of “database narrative”. Since then, we have been able to measure “the growing impact of databases on narrative strategies” (Baroni and Gunti, 2020, p. 42). From the growing range of database narratives, we will focus on one based on real time data flows. The strongest limit imposed on a narrative by real time data flow is that the causality of events is replaced by the sequentiality of real events (Chambefort, 2020), as illustrated in our example below, without narrative mediation. Yet according to consensual definitions (Schmid, 2005, Revaz, 2009), the causal link between events is a sine qua non condition for narrativity, and may even be considered as its constitutive feature. A simple sequence of events or data cannot therefore become a narrative without the intervention of a consciousness and ensuing representation establishing a link between them. At the same time, relying on a real time data flow injects life’s contingencies into the narrative (Chambefort, 2020).

Françoise Chambefort’s Lucette, gare de Clichy (2017) is a web narrative built around a real-time database, as the author explains:

Lucette lives just opposite the Clichy-Levallois station. From her window, she can see travellers passing by, and coming to visit her, or not. The trains, with their strange and familiar bynames, are like characters who pay visits to Lucette. There are very lively moments, and moments of great solitude.

The work is connected to real time through data from the Paris region rail network (the “L” line of the Transilien network). The interface is like a triptych. On the left, train times are displayed (trains may be late, or cancelled), in the middle is a succession of photographs of Lucette, the fictional character, and on the right, we see her stream of thoughts. The viewer’s attention oscillates between the real and fictional poles. If they feel empathy for the character, they will live an exceptional temporal experience and the vulnerability of an old person who has little control over her life (Chambefort, 2020). The train schedule’s calculated time becomes existential time, a waiting period that becomes rich in meaning.

The fact that this creation is not interactive reinforces the temporal experience. The author emphasizes the non-interactivity of her creation, as if to offer greater incitation to the user to pay more attention to old people suffering from loneliness in the physical world. Although Lucette, gare de Clichy is of course built around the calculated time of a real time data flow, it is at the same time a “pure experience of time”, based on the temporal experience of the fictional character (Chambefort, 2020).

Chambefort refers to this work as a “narrative”. If we can speak of a narrative, it is mainly thanks to the words attributed to Lucette and the unifying force of her perspective. Yet Lucette is no doubt situated at the frontier of what constitutes a narrative, just like Bury me, my love. The latter can indeed be categorized as a “narrative game”. Lucette raises the question as to how far we can stretch digital narratives before they cease to be narratives, and whether database narratives may be able to help us deal with the digital data flows we are constantly exposed to, or even to foster a different relationship with them and better situate them in time.

3. From storytelling to storyshowing on social networks: a whole new story

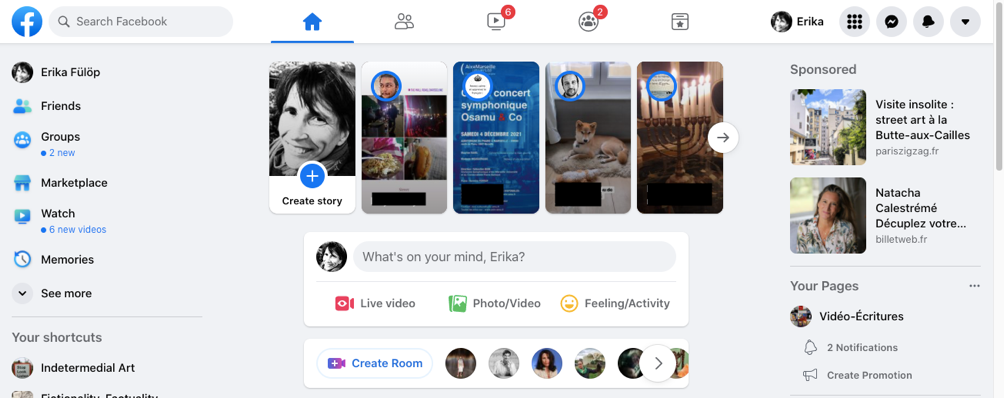

Our third case study concerns the story feature of social media, primarily in its form proposed by Facebook*.* This feature allows users to display content for a limited, twenty-four-hour period, after which it disappears. The content of a story can take all the forms possible for other types of publication, but videos and photos are preferred. Additional functions are proposed to enhance these media with filters, layout templates, or even interactive surveys. Irrespective of whether the chosen medium is temporal / animated (video, gif) or static (photo, text), the length of the story remains limited to 15 seconds, and static media is also presented for 15 seconds, after which the algorithm passes on to the next story in what we could refer to as the viewer’s “storyline.” It is possible to create sequences of photos, videos, texts, but they will always be displayed as a collection of fragments rather than a single continuous video sequence.

From the viewer’s perspective, the story functionality thus creates a succession of fragmented sequences, which, once launched, displays a non-stop chain of stories until the user interrupts it – unlike the newsfeed, which requires the user to repeat an interactive swiping gesture to make publications appear on the screen. Each story must not only adhere to strong temporal (and therefore formal) constraints, but also conform to inclusion in a chain of stories created by algorithms. It is separate from its author’s other publications and what could constitute its context in their life. In fact, Facebook presents stories as “a visual medium which is ideal for sharing authentic moments”, explicitly and deliberately destined to remain fragments. At the same time, the integration of these fragments in the chain of stories of a network of friends contributes to building a form of artificial continuity between the stories of various people – and advertisements – without any causal link among them. Rather than individuals’ “narrative identity,” it is the digital identity of a network that emerges, which is both a continuous flow of visual information and a pixelated image constructed through algorithmic juxtaposition, always in and for the present moment. The individualism behind the self-representation and self-promotion which we might identify as a motivation for users to exploit the story function to share moments of their lives thus paradoxically contributes to a form of deindividuation realised through detemporalization – which itself happens through the minimal temporalization of non-temporal media – whereby each person’s role is limited to enriching the network, in all senses of the term.

Rather than inviting users to tell actual stories**,** Facebook’s official recommendations invite to combine visual attractiveness with speed to capture the viewer’s attention:

Accelerate your rhythm to maintain the attention of your audience; the content of stories is viewed much more rapidly than that of other media. We suggest you create advertisements which capture the audience’s attention right from the first image, and that you conserve their attention by playing on the speed of publication and transmission.

Fragmentation, micro-temporality, a preference for the “show, don’t tell” approach, and the accelerated rhythm inherent in stories are thus greatly motivated by their communicational goal, promotion. Inciting engagement and active participation appears indeed to have been the main goal when stories were first introduced on Snapchat in 2013. According to classical and cognitive narratological theories, narratives provoke reactions in the receiver by appealing to emotions and other cognitive functions through presenting human experiences and making it possible for them to interpret and integrate these in their life experience. This capacity of the narrative is directly linked to the fact that it establishes temporal and causal links. Here we witness a very different logic, aiming at a simple and immediate emotional response, and appealing to the senses (vision, hearing) and to our desire for entertainment and intense immediate reward. Not only does the story fail to impose any criteria for narrativity, then, but due to the relative complexity it implies, narrativity even seems to be an obstacle to the stories’ immediate efficacy. While exploiting the historical success of the concept and the associated practices, the stories of social networks do not rely on narrative structures in the traditional sense.

There is of course nothing new about this tendency towards greater brevity, simplicity, and visual representation; stories merely take this trend to an extreme. The story feature, in its conception as in its construction and the uses it offers, is inseparable from its digital environment, not so much because this environment is by definition and by its very nature detemporalizing, but because the underlying calculations, in both the mathematical and economic-strategic senses of the word, are driven by commercial logic rather than by social or cultural aims. From this perspective, the story simply intensifies the logic behind the strategic uses of storytelling by taking advantage of the potential for emotional impact inherent in stories, but here completely deprived of their (hi)story – in both senses: the past of narratives and the narrative content – as well as of their spirit, since temporality is only useful in this context insofar as it helps to observe changes in behavior – and even then, only the result matters. The problem is therefore not so much that an atemporal calculation is the basis for the functioning of the digital, but rather that its uses are dominated by economic powers which alone have the capacity – both the necessary resources and the accumulated know-how – to invent and implement features to be proposed to users, or even to impose these, by exploiting very human desires and impulses. This does not evidently mean that they cannot inspire imaginative and artistic uses and potentially even (re)invent micronarrative forms in the spirit of flash fiction and microfiction. This is quite certainly happening too and would merit further investigation.

Further Questions

In our current digital environment, constructing and transmitting a narrative in the classical sense of the term, a practice which requires time, or creating experimental forms which question the limits of narrative discourse without immediately providing a satisfactory answer, both imply swimming against the tide alimented by the social networks which dominate our communications. We have presented two fictional works which raise these questions in their own ways, built around two current phenomena in our digital lives, and which do not yet hold an established place in narrative discourse: notifications and data flows. The former allows creators to introduce and integrate fictional time into the reader’s real time, whilst the latter uses the real time of events taking place in the real world to structure a fictional work, lending meaning to a flow of information and transforming it into a human experience. These two examples also show that interactivity and dataflows raise questions around temporality, as this inevitably becomes entwined with that of fictionality and its limits, inviting creators and users to rethink these borders and the traditional binary distinction between fiction and reality. If the classical narrative aims for and encourages the immersion of the reader/viewer through movement from real space-time towards fictional space-time, the new narrative forms enable the emergence of fictional space-time in (and thanks to) real space-time, via a movement that not only crosses, but also deconstructs boundaries.

While these two works question the relations between narrative, temporality and digital environment, our third example invites us to rethink our conception of narrative as it is defined by classical and post-classical narratology, adopting the term and using it to designate entirely different phenomena and practices. This radical otherness also expresses itself through the relation to time – the temporality imposed by the feature, that of the content it proposes, and that of the users. We have seen how the temporality of stories is doubly limited by the networks to an internal duration of a few seconds and to a lifespan of one day. We are in the sphere of the moment(aneous) and the ephemeral, neither of which are designed to foster lasting memories, or at least not to take their place in the archives, but which are nonetheless there to be seen, to have a double (and slightly prolonged) existence, thanks to these forms of representation, but always as moments. The function of these stories is no longer to establish temporal or causal links between events, but simply to include them in what could be referred to as “the life of the network(s)”.

We should, however, avoid essentializing time and think also in terms of digital space (Vitali-Rosati, 2020). Marcello Vitali-Rosati invites us to consider narratives in relation to spatiality rather than temporality. Temporality is linear (before and after), whereas on the web we are especially confronted with “relations of distance and proximity, of visibility and invisibility, of accessibility and inaccessibility, of the central position and the peripheral”, that is to say with creating a space. On the web, we create our collective identity through spatial interactions, and even the notion of “editorialization” is defined by Vitali-Rosati as “the set of dynamics which produce our digital space”. It is precisely in this digital space that stories also take form: the succession of moments, with no other link between them than their juxtaposition by an algorithm and (judging by what we can see) without any consideration for the content, is presented in the digital space, with the frames of each of the stories lined up, available for the user to view. Rather than a narrative sequence constructed by a consciousness, the user receives a sequence compiled by an algorithm. The result is more a question of performance than narrative as construed by Ricoeur, a temporal construction which does not create or modify meaning but nevertheless fills a / the / our digital space.

In 1984, Ricoeur observed that “new narrative forms, which we do not yet know how to name, are already being born, which will bear witness to the fact that the narrative function can still be metamorphosed, but not so as to die”. The question we may ask ourselves today is how extensive this metamorphosis might be, and how far we can push the limits of the “narrative function” without it losing its traditional meaning. Are we today witnessing a fundamental transformation of what we call narrative? Are our desire and need for “old-style” narrative strong enough to resist the planetary tide of atemporal data and moments turned stories, and the networks’ and algorithmic processes’ powers of redefinition? Should we be afraid of such an evolution? Could not such a change be inscribed in the long history of human civilisations, which have already seen so many transformations, including the birth of the narrative as we still know it today?

The above questions suggest that the stake here is not simply what might happen to narrative forms, but what might happen to us without narrative in the classical sense, and how we might function without it. In other words, to what extent are our consciousness and our powers of reflection really dependent on narratives, and how prepared are we to consider alternative modes of functioning? For instance, would thinking by and through network as primary structure be possible, with the cohesion of moments and fragments created by connections other than the temporal and/or causal ones? We may not be facing a total and definitive disappearance of narratives, of course – the opposite tendencies of massive production of long and elaborate narratives both in audio-visual and textual media, from Netflix to Wattpad are just as real and important – but perhaps a relativisation of their place in our culture, history and theoretical constructions, and a multiplication of modes of representing and performing time.

For now, we are nevertheless still inside the system of thought where narrative seems not only indispensable, but also very dominant, beyond which we are yet incapable of thinking. The narrative as a framework for intelligibility can indeed be seen as one of those “great narratives” whose demise was announced by Lyotard, but which continues to structure our perception of the world – the past, the present, and the future. When we tell the story of narrative, and of the evolution of stories on the network, with the challenge they present to traditional narrative, the latter stands firm, supported by the weight of its history, and we too easily confer the role of the “bad guy” to the newcomer, as we in turn enter into the polarizing logic of storytelling. It is only when we open up to the idea that other paths may be possible that we can engage in serious and nuanced reflection about the evolution of our relationship to narrative, to time, and to technology.

References

Bachimont, B. (2010). Le sens de la technique : le numérique et le calcul. Paris: Editions Les Belles Lettres, collection “encre marine”.

Bachimont, B. (2014). “Availability and the transformation of objects into heritage: digital technology and the passing of time”. In B. Dufrêne (Ed.), Heritage and Digital Humanities: how should training practices evolve ? Berlin: LIT, 49-70.

Bachimont, B. (2021). “Écriture et code, motivation du sens et arbitraire du calcul”, seminar “Le champ du signe”, 20th April 2021, ESAD Amiens.

Baroni et Gunti (2020). Introduction à l’étude des cultures numériques - La transition numérique des médias. Paris: Armand Colin.

Bogost, I. (2007). Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bouchardon, S. (2019). “Mind the gap! 10 gaps for digital literature?”, Electronic Book Review. URL: http://electronicbookreview.com/essay/mind-the-gap-10-gaps-for-digital-literature/

Cayley, J. (2018). Grammalepsy. Essay on Digital Language Art. New York and London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Chambefort, F. (2017). Lucette, gare de Clichy. http://fchambef.fr/lucette/.

Chambefort, F. (2020). “Sortir de l’écran: Lucette, Gare de Clichy”. In Gervais, B. and Marcotte, S. (eds.), Attention à la marche! Penser la littérature électronique en culture numérique. Montréal: Les Presses de l’Écureuil - ALN/NT2. pp. 327338. ISBN 979-10-384-0004-7.

Easterlin, Nancy (2012). A Biocultural Approach to Literary Theory and Interpretation. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP.

Fletcher, J. (2012), Introduction to the seminar “Digital Textuality with/in Performance”. University of Falmouth.

Fludernik, M. (2009). An Introduction to Narratology, Londres: Routledge.

Fülöp, E. (2021). “Virtual mirrors: reflexivity in digital literature”. In Fülöp, E. (dir.), in collaboration with Priest, G. and Saint-Gelais, R., Fictionality, Factuality, and Reflexivity across Discourses and Media. Berlin : De Gruyter. pp. 229-254.

Genette, G. (1972). “Discours du récit”, dans Figures III. Paris: Seuil.

Herman, D. (2013). Storytelling and the Sciences of Mind. Cambridge: MIT.

Manovich, L. (2001). The language of New Media. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Mayer, A., Bouchardon, S. (2020). “The Digital Subject: From Narrative Identity to Poetic Identity?”, Electronic Book Review, May 2020. URL: https://electronicbookreview.com/essay/the-digital-subject-from-narrative-identity-to-poetic-identity/

Picard, M. (2021). “La smartfiction, quand l’environnement numérique fictionnel s’hybride à l’environnement numérique personnel”, XXIIème congrès de la SFSIC. URL: https://sfsic2020.sciencesconf.org/333005

Revaz, F. (2009). Introduction à la narratologie. Action et narration. Brussels: De Boeck.

Ricœur, P. (1984). Time and narrative, vol 1. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Salmon, C. (2017). Storytelling: Bewitching the Modern Mind. London: Verso.

Schmid, W. (2005). Elemente der Narratologie. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Stiegler, B. (1998). “Les enjeux de la numérisation des objets temporels”, in Cinéma et dernières technologies, Beau F., Dubois Ph. and Leblanc G (eds.). Paris : INA editions and Brussels: De Boeck & Larcier.

Strawson, G. (2008). “Against Narrativity”, in Real Materialism and Other Essays, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

The Pixel Hunt, Figs, Arte France (2017), Enterre-moi, mon amour, http://enterremoimonamour.arte.tv/

Vitali-Rosati, M. (2020). “Qu’est-ce que l’écriture numérique? ”, Corela [Online], HS-33. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/corela/11759

Zunshine, L. (2006). Why We Read Fiction? Columbus, OH: Ohio UP.

Cite this article

Bouchardon, Serge and Erika Fülöp. "Digital Narrative and Experience of Time" Electronic Book Review, 6 February 2022, https://doi.org/10.7273/31n9-b561