Embraceable Joe: Notes on Joe Brainard’s Art

A comprehensive summary of a career that, unlike those of Warhol, Lichtenstein, Katz or most other contemporaries, lets us recognize Joe Brainard as an antecedent of our current, dispersed and all-embracing digital arts practices. As Nathan Kernan argues in 2019, our multimodal online habitus “looks more and more like a Joe Brainard world.” Wojciech Drąg takes us further into Brainard's lifelong refusal of artistic grandeur. An aesthetic of visual attention that purifies objects and pieces of writing where Brainard wonders if he can ¨get by without saying anything.¨

1 Joe Brainard (1942-1994) is an artist recognized by a relatively narrow circle of devotees, far less famous than some of his friends and collaborators – Andy Warhol, Frank O’Hara, and John Ashbery, though his prodigious artistic output encompasses over a thousand visual works – collages, assemblages, oil paintings, gouaches, and drawings – showing some affinity with Pop Art, Minimalism and camp, as well as more than a dozen literary volumes of what might be termed experimental life writing. Today, his best-remembered works are a series of images of Ernie Bushmiller’s Nancy cast in unlikely, humorous contexts and his 1975 book I Remember, which its very first reader James Schuyler called “a great work that will last and last” and which, four decades on, The New Yorker deemed “one of the twenty or so most important American autobiographies” (Chiasson). In the last years, Brainard appears, at last, to be gaining the recognition he deserves. Edinburgh University Press has just released the first edited collection focusing exclusively on his output – Yasmine Shamma’s Joe Brainard’s Art (2019). In the book’s afterword, Marjorie Perloff calls him “an artificer of the natural whose time has surely come” (255). The year 2019 also saw a large retrospective of Brainard’s works at the Tibor de Nagy Gallery in New York and the launch of the “Make Your Own Brainard” website funded by the British Academy. While history knows countless instances of artists winning acclaim only after their death, his case is unique on account of the kind of following that he has commanded; “To know Joe Brainard’s art,” Shamma proposes, “is to become viscerally attached” (16). This essay will outline the major areas of Brainard’s artistic activity and consider the reasons for the current rise of interest in his work. It will suggest that the phenomenon of Brainard’s appeal rests partly on the poignant fusion of his life and art.

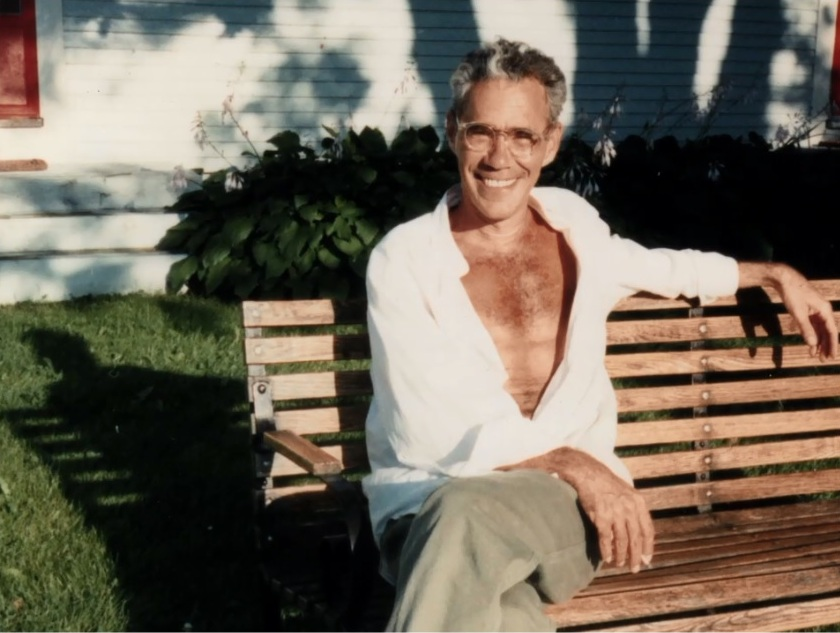

photograph by Lorenz Gude

Courtesy of the photographer

Brainard – the man

Though born in Salem, Arkansas, Brainard spends his childhood in Tulsa, Oklahoma.2 His precocious artistic talent becomes apparent when, as an eight-year-old, he designs a gown for his mother. He goes on to conceive women’s clothes on a regular basis and wins numerous art competitions in Tulsa, for children and adults alike, including the 1957 Women’s Christian Temperance Union contest for the best poster. In 1960, together with his best schoolmate – and the future New York School poet and author of Joe: A Memoir of Joe Brainard (2004) – Ron Padgett, Brainard leaves Tulsa for New York City, where, with short intermissions, he will remain until his death thirty-four years later. In order to be there, he quits Dayton Art Institute in Ohio, where he has been offered a scholarship, after only a couple of weeks of study. That moment marks the end of his formal education in the visual arts, amounting to several years of individual classes in Tulsa.

His first years in New York (and a brief spell in Boston) are a time of very intense exploration of his artistic vocation,3 sexual orientation (first homosexual experiences), and the opportunities of city life. It is also a period of nearly permanent poverty, when Brainard is forced to sell blood, shoplift, order fries and water in bars for dinner, and sleep alternately in a single bed with his Tulsa friend and poet Ted Berrigan. His days are filled by creating collages, designing covers and illustrations (for magazines and his friends’ poetry collections), and writing autobiographical prose. In 1965, thanks to Ashbery’s endorsement, Alan Gallery hosts his first solo exhibition made up largely of altar-like assemblages featuring icons of the Virgin Mary. It is also the year of his first visit to Europe, with Kenward Elmslie – writer, performer, and the grandson of Joseph Pulitzer. For almost 30 years, Brainard and Elmslie will be partners and artistic collaborators. Though Brainard will form other relationships – most notably with writer Joe LeSueur and actor Keith McDermott – and have numerous other lovers (among them the novelist and memoirist Edmund White, the author of A Boy’s Own Story), the companionship with Elmslie will remain central to his life. Elmslie’s estate in rural Vermont is where Brainard will spend most of his summers and where his ashes will be scattered in 1994. Although Brainard was an avowed homosexual living in New York in the 1960s, there are no references to the nascent gay rights activism of the Stonewall era in his published diaries and letters of the time.

The time between 1965 and 1976 is the most productive and successful decade in Brainard’s career. He has a number of solo shows in New York, including four exhibitions at Fischbach Gallery, in Salt Lake City, Philadelphia, Chicago, Kansas City, as well as in Paris and Australia. He regularly publishes short autobiographical works, such as Bolinas Journal (1971) – an account of his two-month stay in California. He also works on consecutive installments of what will become his magnum opus – I Remember, whose definitive edition is released in 1975. That year, he also assembles his largest and perhaps most important exhibition – a solo show of 1500 miniature paintings and collages at Fischbach Gallery. In that most creative and intense period of his career, Brainard regularly relies on speed and amphetamine.

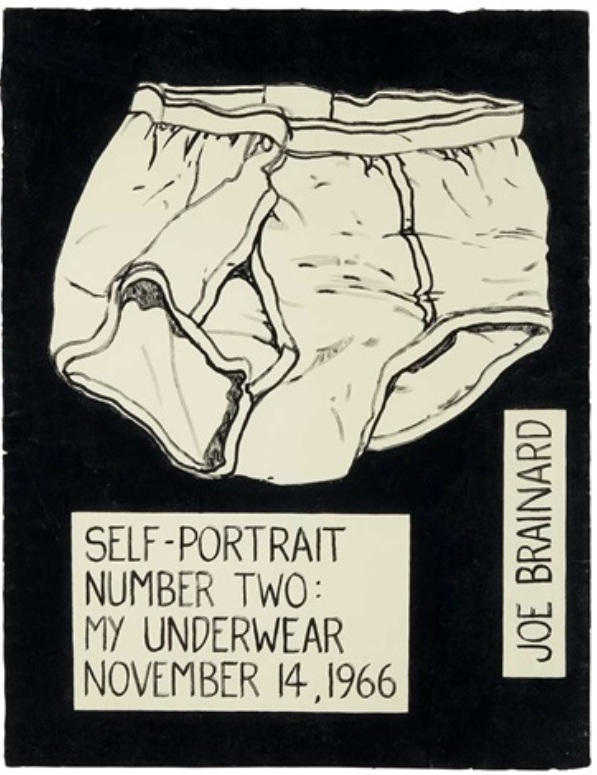

mixed media collage, 13 7/8 x 10 3/4 inches

Joe Brainard Papers, Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego

Used by permission of the Estate of Joe Brainard and courtesy of UC San Diego

In the early 1960s, Brainard makes friends with the most significant representatives of the New York School – Ashbery, O’Hara, James Schuyler, and Kenneth Koch. He collaborates with O’Hara on a series of collages, designs the cover and illustrations for several of Ashbery’s publications (including The Vermont Notebook from 1975)4 and develops numerous artistic projects with old Tulsa friends – Berrigan and Padgett. He also meets some of the most illustrious artists of the time – his favorite painter Willem de Kooning, Andy Warhol (who even throws a birthday party for him in the late ’60s), Jasper Johns, David Hockney, and Alex Katz (the last three have posed for Brainard’s portraits). He attends various galas and parties during which he makes the acquaintance of some of that era’s greatest celebrities: Jacqueline Onasis, Montgomery Clift, and Anthony Perkins. At a festival in Italy, he is introduced to Ezra Pound, who, according to Brainard’s account, failed to say a single word to him and kept rolling his eyeballs around, looking “like he belongs on a coin” (Padgett 88).

In the late ’70s, Brainard decides to step out of what he perceives as the increasingly mad New York art world and resolves not to exhibit new work anymore. Exhausted by the frenetic pace and the “labor-heavy competitiveness” of the visual art scene (Sturm 189), whose demands he has tried to meet by wrecking his health through excessive drug use, Brainard renounces his dream of matching the achievements of the contemporary artists he idolizes.5

He consistently declines invitations to show his work, which he regards as not sufficiently strong. However, he occasionally agrees to contribute his drawings to some collaborative projects. Throughout the ’80s, Brainard lives a life diametrically opposed to his earlier speed-induced pursuit of artistic development. In 1989, he summarizes his daily routine: “Mostly I just draw and read, go to the gym, and see friends. A real nice life” (Padgett 286). His last years are spent under the shadow of the AIDS diagnosis and the exhausting treatment. He is looked after by Pat Padgett, a fellow Tulsan, the wife of Ron, and a close friend from the age of seventeen. In 1994, Brainard dies of AIDS-induced pneumonia.

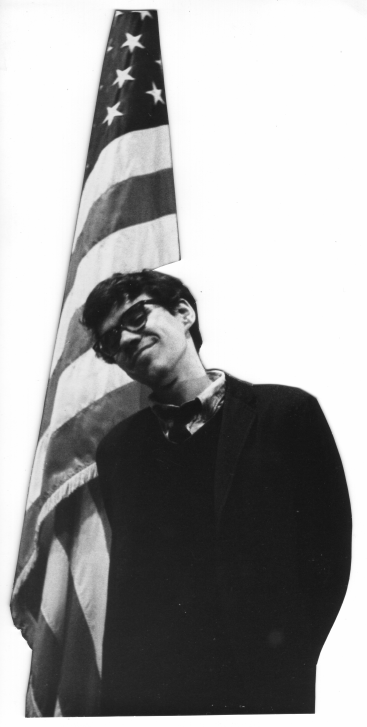

ink on paper, 28 x 22 inches

Estate of Joe Brainard

Used by permission of the Estate of Joe Brainard and courtesy of Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York

Brainard – the visual artist

Until his late thirties, Brainard had been an extremely prolific artist, with a dozen individual publications, over a dozen collaborative book projects and a couple of thousand visual works to his name. Today, when The Collected Writings of Joe Brainard (2011), edited by Ron Padgett and with an introduction by Paul Auster, is out from The Library of America and Brainard’s collages, assemblages, drawings, and small paintings are in the permanent collections (though rarely on display) of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art, it is difficult to assess whether he has won more acclaim as a writer or visual artist. It is indisputable, however, that Brainard saw himself primarily as a collagist and painter, and that he devoted far more time and attention to those art forms than to the writing of prose.

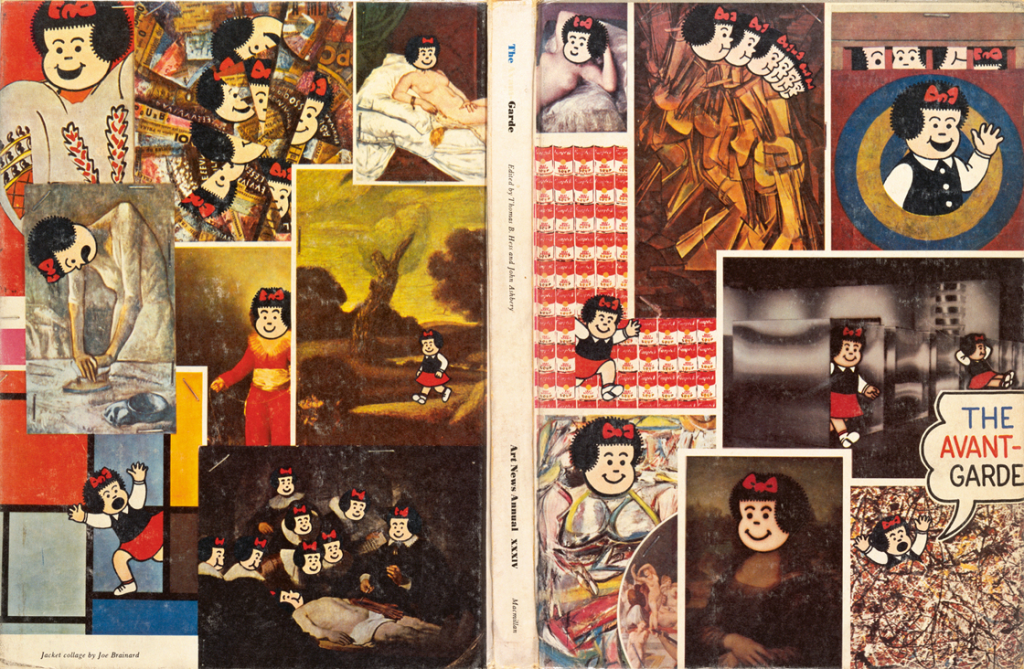

In contemporary criticism, there is little consensus on how to classify Brainard’s visual output. The most frequently associated label is that of Pop Art, whose poetics shares with Brainard’s an avid interest in comics and appropriation. The two are combined in The Nancy Book (only published in 2008), a collection of 1970s collages featuring the likeness of Ernie Bushmiller’s character Nancy, a precocious and self-assured eight-year-old heroine of the comic strip Fritzi Ritz. In the best-known works of the series, Nancy is proudly presenting her tiny penis (If Nancy Was a Boy) and has a large cigarette stuffed into her mouth (If Nancy Was an Ashtray, both 1972). Many other portraits of Nancy incorporate her head into the likenesses of iconic paintings by Rembrandt, Marcel Duchamp, Willem de Kooning and other canonical artists (figure below). The effect of the collage-like superimposition of Nancy’s smiling face on the miniatures of The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp or Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 is invariably comic. Besides hoping for the audience’s amused chuckle, those works perform a postmodernist gesture of deflating (in Brainard’s case, rather good-naturedly) the aura of seriousness and pomposity surrounding much of avant-garde art (particularly in the context of Duchamp, de Kooning, Piet Mondrian, and Jackson Pollock). Another shared interest with Pop Art is Brainard’s fascination with consumer culture. Many of his collages and assemblages appropriate the logos and packaging of popular labels, such as Lucky Strike, Chesterfield, and Tareyton cigarettes (e.g., Hi Folks!, 1965), Hershey’s chocolate bar (Pope Weak, 1964), and the Good’n Fruity multicolored candy (Good’n Fruity Madonna, 1968).6 Even some of his paintings – such as 7 Up (1962) and Pepsi-Cola Black-Eyed Susans (1969) – make the commercial label the focal point of the work. Finally, Brainard’s friendship with Andy Warhol and his admiration for Warhol’s work7 are seen as reinforcing his ties to the Pop Art movement. The most evident testimony to his influence is Brainard’s recurrent treatment of pansies (see figure 9), whose vivid color palette – dominated by synthetic yellows, oranges, purples, and pinks – is strongly reminiscent of Warhol’s flower prints from the 1960s.

offset lithography, two pages 9 x 12 inch each

Location unknown

Used by permission of the Estate of Joe Brainard and courtesy of Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York

Despite those aesthetic similarities, several critics have expressed reservations about classifying Brainard as a Pop artist. Constance M. Lewallen argues he was never one “in the strict sense,” since his “affection” for popular culture clashed with the “ironic distance” towards the products of mass media adopted by artists like Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein (10). Edmund White also contrasts their “adversarial position against everyday images” with Brainard, who “liked everything” (239). Nathan Kernan, in turn, stresses the difference in their treatment of people: in Warhol, they become “things” or “icons,” while in Brainard the reverse process occurs – religious and popular icons are “de-iconized,” turned into “objects of empathy” (44). A fine example of Brainard’s affectionate treatment of popular culture is the earlier mentioned gouache work Pepsi-Cola Black-Eyed Susans (figure below), where a bottle of Pepsi – an icon of consumerism – is embedded in a symmetrical, highly aestheticized composition and serves as a vase for fresh flowers, its wavy logo harmoniously blending with the floral surroundings. Brainard’s humanization of iconic figures can, in turn, be illustrated by his numerous collages and assemblages appropriating holy pictures of the Virgin Mary with Jesus. In many of them, the devotional images are democratically combined with objects of everyday use such as candy packaging (Good’n Fruity Madonna), empty shampoo bottles (Prell, 1965), and newspaper cut-outs (Mater Dolorosa, 1966).

gouache on paper, 13 1/2 x 10 1/2 inches

Collection of Kenward Elmslie

Used by permission of the Estate of Joe Brainard and courtesy of Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York

Other labels seem less relevant to Brainard’s artistic output. Although he admired the Abstract Expressionists – particularly de Kooning, whose cigarette butt was salvaged by Brainard during a New York function and placed like a relic in the middle of his Cigarette Smoked by Willem de Kooning (1970) – and some of his works are visibly indebted to theirs (e.g., the frequent use of the American flag in a manner reminiscent of Jasper Johns), he denied any major connection between his and their artistic paths. “I think I’m sort of the reverse of that,” he said in 1977, pitting the Abstract Expressionists’ “high seriousness,” the imperative to “spill out your guts all over,” against his own spontaneity and lack of ambition to pursue some artistic ideal – his preference to “start from nothing and just surprise [himself]” (Interview by Dlugos 502). Brainard’s occasionally detectable debt to Minimalism is pointed out by Lewallen, who concludes, however, that he was “too protean to be stuck with Pop or any other label,” as he “drew his materials and images from everywhere” (10, 26). “I have so many different ideas all at once,” Brainard explained, “that I can’t get them all done, nor really develop any of them” (qtd. in Kernan 74). His lack of patience to explore the full potential afforded by a given method cannot be attributed only to a character flaw (as Brainard tended to see it) but also to the artist’s resolution for his style never to consolidate. “The thing I am afraid of most in life is being ‘Brainardesque,’” he stated in 1970 (Padgett 179). While he looked up to de Kooning, Warhol, and Katz as artists, he did not wish to develop a signature style as recognizable as theirs; he was afraid of producing “a new Brainard” in the way that one could speak of “a Warhol,” “a Katz,” or “a Lichtenstein.”

In the exhibition catalog of Brainard’s first major posthumous retrospective, Lewallen argues that “once he had mastered a technique or taken an idea as far as he could, he habitually moved to something new” (28). As a result, Brainard left an unusually varied output of mixed media collages, paper cut-outs, assemblages, oil paintings, enamels, gouaches, as well as pencil, ink, and graphite drawings. His range of subject matter is almost as diverse: people (portraits of friends and fellow artists, such as Katz, Johns, and David Hockney),8 dogs (Elmslie’s majestic whippet named Whippoorwill), still lifes (minimalist renderings of scallions, cherries, apples, and pears, which Lewallen likens to the miniatures of Édouard Manet – one of Brainard’s favorite painters [31]), flowers and floral patterns (roses, daffodils, and – most characteristically – pansies), and landscapes (rural Vermont). Despite that rich variety, one can certainly single out the signature, Brainardesque, elements which recur throughout his career: Virgin Maries, Nancies, pansies, and cigarettes. The latter serve as the focus of Brainard’s largest oil painting – Cinzano (1974), which is composed of sixteen near-identical miniature still lifes of cigarette butts in a triangular ashtray, and as the background of several of his assemblages.9 Besides those recurrent images, another constant in his output – perhaps the most readily discernible one – is the modest size of his works. Many of his collages and ink drawings are as small as 6 x 4 inches (the smallest are 2 x 2 inches), the Nancy series and most oil paintings are 12 x 9 inches, while his largest oil work – Cinzano, at 48 x 36 ½ inches, remains over half as large as Warhol’s Double Elvis (1963). For Brainard, the vast size of many contemporary paintings was indicative of the increasing self-importance and commodity status of the New York art world. His last major show – at Fischbach Gallery in 1975 – during which he presented 1500 miniature exhibits, some of them as small as a subway ticket and priced at as little as 25 dollars, can be regarded as an act of defiance against the dictates of the art market (Padgett 222-23).10

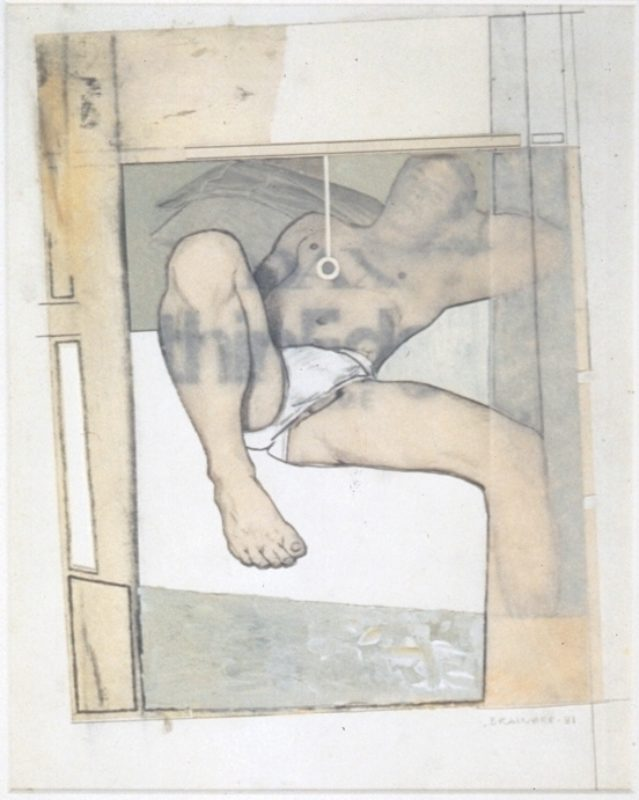

“The current visual art scene,” argues Kernan in 2019, “looks more and more like a Joe Brainard world.” Among the many manifestations of his “prescience” Kernan considers his use of “witty” and “cartoon-like” illustrations on paper (reminiscent of the work of contemporary artists such as David Shrigley), materially extravagant assemblages (Mike Kelley) and of openly homoerotic content (Rene Ricard). An example of the latter is Brainard’s Untitled (Reclining Nude) from 1981 (figure below) – one of his many collages featuring a Xeroxed image from a pornographic magazine presenting a nude (or nearly nude) man in a suggestively erotic pose. The added roller blind and framing window put the viewer in the position of a voyeur who can at any moment pull the string and cover the erotic performance. Several of Brainard’s male nudes fuse pornographic content with incongruous images, such as drawings of a pear and a cucumber in place of the erect penis in Untitled (Heinz) (1977), which deflates the sexual motivation of the scene.

Kernan notices that Brainard’s programmatic “inconsistency” and refusal of a signature style has been practiced by artists such as Richard Prince, Ugo Rondinone, and Jiri Georg Dokoupil (43). Lewallen, in turn, stresses that Brainard’s Madonna collages and assemblages anticipate the Pattern and Decoration movement and the work of Thomas Lanigan Schmidt, who has drawn on Brainard’s strategy by combining “Catholic ritual icons” and “dimestore materials” (15, 26). According to Lewallen, it is Brainard’s “gay sensibility” – with his use of kitsch material and imagery, his “camp love of artifice and style over content,” and his “frank sensuality” – that would most likely situate him “in the mainstream” of the contemporary art scene, together with artists such as Jim Hodges, who “risk excess in pursuit of charm.” In the 1960s and ’70s, however, Brainard’s fondness for that aesthetic “kept him on the margins” (18).

collage, 14 x 11 inches

Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York

Used by permission of the Estate of Joe Brainard and courtesy of Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York

Brainard – the writer

Brainard’s first forays into writing come from the early 1960s, when he had just left Tulsa for New York. His literary juvenilia, like “Self-Portrait on Christmas Night” (1961), written at the age of nineteen, are entirely autobiographical and unashamedly self-absorbed. In “Back in Tulsa Again” (1962), the first of his successful travelogs, his writing displays some of the distinctive characteristics of his mature work: self-reflexivity, digressive tendencies, and playfulness – linguistic as well as compositional (the latter exemplified by a section called “A List for the Sake of a List,” which facetiously enumerates the traits of the text’s three protagonists – Brainard, Padgett, and Padgett’s girlfriend Pat Mitchell). The great majority of his writing from the 1960s are diaristic texts whose primary interest lies not in their literary value (most of them are hit and miss) but in the insight they afford into Brainard and his circle of eminent friends.

The turning point for Brainard’s literary career came with the publication of I Remember – the first in a series of four short pieces released between 1970 and 1973 and composed of very brief (often one-sentence long) autobiographical entries beginning with the words “I remember…” All the installments were merged into a single volume and published under the same title in 1975. The merits of the most acclaimed of Brainard’s projects will be discussed in a separate section. The success of its first part, together with Brainard’s growing recognition as an artist, enabled him to find the publisher for several zany projects like The Cigarette Book, The Banana Book, and The Friendly Way (all 1972), the latter a collage of fragments appropriated from women’s magazines.11 The 1970s saw the publication of twelve of Brainard’s book publications, most of which amount to the size of brochures or booklets. Their very titles – Some Drawings of Some Notes to Myself (1971), 12 Postcards (1975), 29 Mini-Essays (1978), 24 Pictures & Some Words (1980) – convey a sense of their structure and form. They are invariably autobiographical (if not confessional, then at least firmly rooted in his experience as a New York artist), multimodal (creatively blending text and image, often following the poetics of the cartoon), aphoristic (e.g., 29 Mini-Essays contains jokey reflections on a range of subjects from The Beach Boys to Women’s Lib), anecdotal (“John Ashbery was a quiz kid,” the reader learns from one of the 37 entries of his “Little-Known Facts about People” [230]), and fragmentary (always preferring a seemingly random arrangement of snippets to a coherent structure).

In his diaristic texts, Brainard shows a fondness for negating what has just been said, thus creating a sense of inner dialog; in all of his literary works, he uses a great number of parenthetical interjections and qualifications. When the two are combined, the effect is unmistakably Brainardesque:

But on the other hand – who wants to be realistic? Not me. (Tho I am.) No I’m not. (qtd in Padgett 181)

If you want to know what it’s like to have a rug pulled out from under you (don’t bother) (and besides, I’m sure you already know) try having a show. I’ve never felt so totally empty in all my life. So empty I don’t even feel bad (?). Actually, I do. I feel like shit! (Brainard, N.Y.C. 371)

You won’t know me. (You will.) (qtd. in Padgett 148)

The last example comes from Brainard’s letter to a friend in which he talks about his improved looks on account of the recently adopted healthy lifestyle. The parenthetical “you will” is a modest retraction of the rhetorical excess of the previous statement and, at the same time, a playful probing of casual hyperbole. Brainard’s uneasiness about words and their misleading connotations frequently makes him resort to unnecessary quotation marks.

Brainard’s literary method, if indeed method is not too grand a word for his largely spontaneous creations, can be exemplified by one of his shortest pieces:

Two Things I Have Never Had Are:

- an identity crisis

- sex in the kitchen. (qtd. in Padgett 182)

By placing the enumerated elements on the same level, Brainard achieves the humorous effect often generated by zeugma – the use of a word (here, “to have”) in two incongruous meanings or as part of incompatible phrases. What accentuates that effect is the anti-climax of the second component, whose crudeness clashes with the hint of sadness conveyed in the negative title and the seriousness of the first element. “Two Things” is a quintessential Brainard piece also on account of its autobiographical framing. Although the punchline appears to undermine the text’s confessional tone, the reader familiar with Brainard’s writing will recognize in the closing passage an expression of sexual anxiety – the sense of missing out on sexual possibilities, which underlies much of his diaries. The text can thus serve as an example of a Brainardesque fusion of the confessional and the playful, its minuscule form symptomatic of the author’s consistent refusal of any form of artistic grandeur. At the same time, it may be criticized for being flippant, puerile, and somewhat showy. Similar charges can be laid against some of Brainard’s other miniature pieces, such as “No Story” (1972), which consists of the following statement: “I hope you have enjoyed not reading this story as much as I have enjoyed not writing it” (436).

Literary critics tend to situate Brainard’s oeuvre in the context of the New York School, which emphasizes the artistic influence of the circle of his closest friends, which he himself saw as the main motivation for his literary activity. “I think I write,” Brainard once stated, “because I know a lot of writers” (Interview by Waldman 512). Predictably, it is possible to draw numerous parallels between his work and that of his poet friends: particularly his favorite poet Frank O’Hara and James Schuyler.12 Rona Cran, a New York School critic and the creator of the Make Your Own Brainard website, sees the following common points between O’Hara’s and Brainard’s writing: “an extraordinary lightness of touch in writing about sorrow or fear or insecurity,” “a desire to be liked,” and “an interest in the generative possibilities of everyday experiences, rather than relying on ‘ideas.’”13 Brainard and Schuyler, on the other hand, are both “consummate and detailed ‘lookers,’” whose active engagement and close attention preclude the detachment and neutrality of a mere observer (Cran, “Re: Here”).

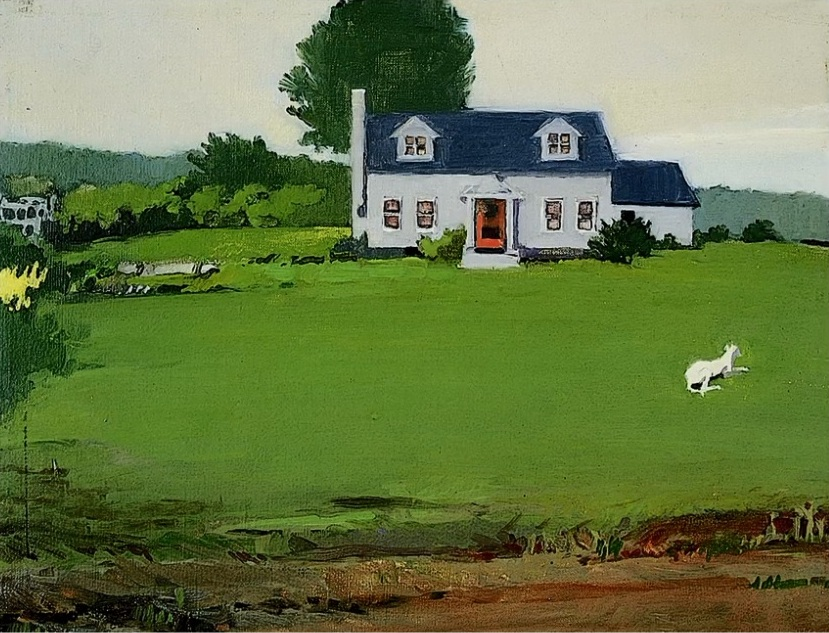

oil on canvas, 9 x 12 inches

Collection of Kenward Elmslie

Used by permission of the Estate of Joe Brainard and courtesy of Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York

The best example of Brainard’s debt to O’Hara and Schuyler – particularly of his dedication to exploring “the generative possibilities of everyday experiences,” to an avid form of “looking”, and to what Perloff has called “the aesthetics of attention” (in her seminal article on O’Hara) – is his short diaristic text “August 29th, 1967.” In it, Brainard commits to perceiving and recording meticulously the present moment, a lazy summer morning. His account opens like this:

I’m outside sunbathing on Kenward Elmslie’s lawn in Calais, Vermont. I would say that it’s about 10 o’clock. I’m all covered with suntan lotion. The sun is not shining. The sky is total gray clouds. You never can tell about Vermont, tho. It might clear up at any moment. Wayne is crying. Now he’s laughing. Wayne is Pat and Ron Padgett’s new baby boy. They’re up here too. And so is Jimmy Schuyler. He’s still asleep in the front bedroom. (218)

As the moment-by-moment account of – to use Schuyler’s phrase from “February” – “a day like any other” continues, Brainard begins to consider the validity of such a project: “Already I am thinking of this as a ‘piece of writing,’ and wondering if I can get by without really saying anything” (218). His doubts about the value of writing (and painting) whose sole ambition is to do justice to how the world appears to the looker at a given point in time find even more precise expression in “Diary 1969 (Continued),” where Brainard muses,

What I really hope for, I guess, is that, by just painting things the way they look, something will ‘happen’ … In much the same way, I am writing this diary now. I am telling you simply what I see, what I am doing, and what I am thinking. I have nothing that I know of in particular to say, but I hope that, through trying to be honest and open, I will “find” something to say. Or, perhaps, what I really hope for, is that the simplicity of the writing will be interesting in itself. (243)

The above can be regarded as Brainard’s artistic credo – the pursuit of self-expression for the sake of it, the hope for value and interest arising not from the experimental form or the original content but from the unconditional dedication to honesty and simplicity.

In “August 29th, 1967,” Brainard turns at one point from the exploration of what is happening around him to what is on his mind. He mentions his desire to please others, his being “a nice person,” his lack of morals, his artistic shortcomings (“There is something that I lack as a painter that de Kooning and Alex Katz have”), his love of people (“I’m going to get corny if I don’t watch out”) and, finally and seemingly anti-climactically, his wish to “have a giant dick” (218-19). What in any other piece might sound like a poor attempt at being funny or shocking here reads like a subtle triumph of honesty – the admission of an embarrassing and crude thought, delivered in a manner free of calculation and other negative aspects of exhibitionism. In the same vein, in “Wednesday, July 7th, 1971,” Brainard considers the areas that so far have been too embarrassing for him to admit in his writing, among them the addiction to speed and the continued financial reliance on his partner Kenward Elmslie. He then clarifies, “Taking [his money] doesn’t embarrass me at all. Seems only natural, as he has lots and I have little. What embarrasses me is admitting to others I take it” (338). In passages like this, Brainard’s unconditional honesty and vulnerability win the reader’s trust and sympathy; candor, argues Edmund Berrigan, is the major “inviting entry point” into his work (35).

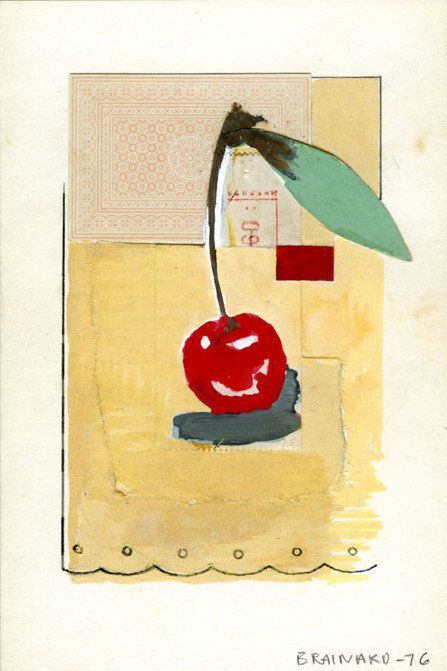

Another access point is what Brainard calls “simplicity of writing” and what Cran refers to as his “lightness of touch” – the disarming directness, straightforwardness, and lack of pretension, which have made Schuyler remark that “there’s never any fuzz” about Brainard’s writing (qtd. in Padgett 311). Padgett attributes those qualities to “the clarity of his prose style, its short declarative sentences, and its avoidance of ornamentation and Latinate vocabulary” (311). The same clarity, directness, and desire to strip his subject matter to the bare essentials marks his visual works, particularly his still lifes – of a tomato, of a can of sardines or of four toothbrushes in a holder. The minimalist rendering of a single cherry in the collage Untitled (Cherry) from 1976 (figure below) is a case in point – a visual equivalent of O’Hara’s “aesthetics of attention.” “Sometimes,” Brainard wrote in a letter to Schuyler, “what I do is to purify objects” (qtd. in Padgett 312).14

mixed media collage, 6 x 4 inches

Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York

Used by permission of the Estate of Joe Brainard and courtesy of Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York

I Remember

The pinnacle of Brainard’s literary achievement, I Remember has gained cult status in certain circles and has received a fair amount of academic attention.15 The distinguished group of its champions includes Georges Perec, Harry Mathews, and Paul Auster. Perec and Mathews paid homage to it by adopting Brainard’s formula in their own writing, while Auster contributed an enthusiastic endorsement16 to the 2001 edition of I Remember and an introduction to the earlier mentioned Collected Writings volume. The book’s success lies in a combination of qualities that rarely results in a literary masterpiece – a disarmingly simple form and scrupulously honest content. Formally, I Remember consists of close to 1,500 snippets which consistently begin with the titular phrase and whose length rarely exceeds a single sentence. Despite its apparent lack of complexity, the structure of the book has been compared by critics to a collage (Shamma 10-11), an assemblage (Laing), a mosaic (Fitch 78), a litany (Epstein), and a fugue (Auster, Introduction xix). The content is supplied by Brainard’s memories, from his childhood in Tulsa to his first decade in New York.

The method can be illustrated by the following two excerpts from the opening pages of the book:

I remember my first cigarette. It was a Kent. Up on a hill. In Tulsa, Oklahoma. With Ron Padgett.

I remember my first erections. I thought I had some terrible disease or something.

I remember the only time I ever saw my mother cry. I was eating apricot pie. (7-8)

…

I remember “How Much Is That Doggie in the Window?”

I remember butter and sugar sandwiches.

I remember Pat Boone and “Love Letters in the Sand.” (13)

While the former, confessional, passage discusses memories of an intimate nature, the latter focuses on recollections related to American popular culture of the 1950s and ’60s.17 Despite their overtly autobiographical basis, both sets of memories are presented in such a way as to invite the reader to retrieve their own corresponding recollections. At times, he manages to generate in his audience the effect comparable to reading an account of one’s own life but written by another. There are several devices that enable Brainard to reach that level of identification: the use of the first person, the dismantling of an individual life narrative (with its chronology and other peculiarities) into minuscule components of life (moments, thoughts, feelings) and accentuating experiences whose character is more universal than unique and self-defining.

I Remember abounds in accounts of memories that are highly relatable to Brainard’s contemporaries, as well as to readers born decades later and in countries very different from America. Below is a small selection of such entries:

I remember playing “doctor” in the closet. (12)

I remember daydreams of dying and how unhappy everybody would be. (29)

I remember slipping underwear into the washer at the last minute (wet dreams) when my mother wasn’t looking. (35-36)

I remember staying in the bathtub too long and having wrinkled toes and fingers. (54)

I remember being embarrassed to buy toilet paper at the corner store unless there were several other things to buy too. (61)

I remember walking home from school through the leaves alongside the curb. (88)

I remember the fear of not getting a present for someone who might give me one. (90)

In those passages, Brainard captures a number of minor anxieties, realizations, and passing thoughts that could have been experienced by many of his readers. What reinforces the pleasure of self-recognition is the confrontation of one’s conviction that such perceptions are peculiar to oneself with the evidence that they are shared with another, possibly with many. Gary Weissman sees I Remember as a work that “questions just how unique and idiosyncratic are one’s most private and personal experiences and sentiments,” as well as evokes a “sense of how much one is like others” (78).

While working on the first installment of his project, Brainard wrote in a letter to Anne Waldman that he felt I Remember “is about everybody else as much as it is about me” (qtd. in Padgett 171). However, he chose not to gloss over the memories which clearly mark out his experience from that of the majority of the book’s audience – his homosexuality:

I remember one football player who wore very tight faded blue jeans, and the way he filled them. (19)

I remember a boy. He worked in a store. I spent a fortune buying things from him I didn’t want. Then one day he wasn’t there anymore. (28)

I remember jerking off to sexual fantasies involving John Kerr. And Montgomery Clift. (41)

I remember getting up at a certain hour every morning to walk down the street to pass a certain boy on his way to work. One morning I finally said hello to him and from then on we said hello to each other. But that was as far as it went. (165)

Brainard proves capable of eliciting strong identification even while sharing experiences that, in the 1960s in Tulsa, singled one out as a social outsider. He achieves this by drawing on the universal reservoir of romantic archetypes, particularly that of unrequited love, with its motifs of doomed attempts to attract the loved one’s attention and of sexual frustration. There are moments in the book when Brainard subtly veers towards the kitsch of the poignancy of lost childhood innocence or unhappy love, but the reader has no sense of any calculated effort to generate specific affects through overt nostalgia or sentimentality.

watercolor and collage on paper, 28 x 22 inches

Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York

Used by permission of the Estate of Joe Brainard and courtesy of Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York

Embrace the pansy

In several significant ways, I Remember is representative of Brainard’s entire output, literary and visual, and so it may hold the key to its recently won popularity. It is the perfect embodiment of Brainard’s earlier asserted “lightness of touch” and lack of “fuzz.” It appears as effortless as some of his ink drawings and miniature still lifes. It “disarms” the audience with what Auster calls “the seemingly tossed-off, spontaneous nature of his writing” (Introduction xxv) and what Perloff attributes to the “fragmentary quality … tentativeness and lack of finish” of his artistic method. Those very aspects of Brainard’s output – its eschewal of any kind of formal or thematic grandeur and monumentality – situate him near the pole of “minor art,” traditionally conceived as a demeaning category. Art critic Brian Glavey argues that Brainard’s “investment in minor aesthetic categories” – such as “contentment” instead of “elation,” “glumness” in place of “despair,” “horniness” rather than “passion” – is one of the main reasons for his relevance to the contemporary moment, when “critical vocabularies are shifting.” For Glavey, I Remember is “a conceptual machine for producing minor affects” (“Friendly Way” 140). Such affects spring from Brainard’s mellow poetics of the everyday and from his denial of a larger, metaphysical or existential, context. For Weissman, I Remember taps into the Zeitgeist by skillfully blending “the candid, the idiosyncratic and the banal” (98) – categories that dominate the content of social media today. What in Brainard’s art appears as “minor” is, according to Yasmine Shamma, “deceptively diminutive” and holds “depths” that “linger” (15-16). Brainard’s curious oscillation between minor and major has been asserted by several critics: Kernan notes that “any potential bigness in his work was distilled … into the smallest possible space” (46), whereas Auster argues that I Remember “begins and ends small, but the cumulative force of so many small, exquisitely rendered observations turns his book into something great.” Auster regards that poetics of “smallness” as rooted in Brainard’s “gentleness,” “lack of pomposity,” and “imperturbable interest in everything the world offers up to him.” Unlike the more acclaimed confessional authors of the time – Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton, and John Berryman – he confesses without “ranting” and has no intention of “mythologizing the story of his own life” (Introduction xxiv).

Another distinctive quality of Brainard’s oeuvre, also exemplified by I Remember, is its capacity to elicit an aesthetic response in the audience which forges a bond between the reader/viewer and the artist. Ashbery describes the effect of Brainard’s visual work as a mixture of “gratitude” and “pleasure” (1). “An onrush of gratitude,” “something too happy for thinking” and the sense of being “in touch with how amazing and beautiful the world looks” are the sensations experienced by Padgett upon seeing Brainard’s work (175). For Edmund Berrigan, it is a feeling of “joy” accompanied by “vulnerability” (34). According to Padgett, the strong aesthetic and affective response evoked by his art tends to suppress the need for interpretation. When confronted with his work, he observes, “most of us … can’t think of anything to say except ‘That’s beautiful’” (135-36). Fellow poet Alice Notley agrees, “I think of Joe’s work as being beautiful, first; it seems to me now my first impression, or feeling of it, was of my being allowed, finally, to experience what I thought of as beautiful, as beautiful” (21). The centrality of the notion of the beautiful to the experience of Brainard’s art is implicit in Shamma’s original choice of title for her edited collection on his literary and visual work, which was the phrase “Too Beautiful” (Cran, Personal interview).

In Shamma’s introduction to the book, ultimately titled Joe Brainard’s Art, she claims that his art is “precisely the kind one gets ‘attached to’” and later gives the earlier cited remark that “to know Joe Brainard’s art is to become viscerally attached” (4, 16). While I agree with those statements and count myself as one of the viscerally attached, I cannot, and neither does Shamma, account for that phenomenon. Some light is shed on the matter by Ashbery, when he muses on the radically different response elicited by the work of Brainard and Warhol. However much one may admire the Campbell soup painting, it does not inspire the wish to “cozy up to it.” In the case of a Brainard pansy, on the other hand, “one wants to embrace the pansy” (1). The need to “embrace” a work springs partly from the sense that the artwork and the viewer are on the same plane, not separated by any divide. “Nothing was standing between me and it” is how Notley describes her first contact with a Brainard work (21). When analyzing his still lifes, Cotton proposes that Brainard “does away with the idea of art as a distant thing to be looked at,” because of the intimacy, openness, and materiality of his representations of everyday objects (93). The simplicity, honesty, and relatability of I Remember generate a similar sense of closeness in response to a written text.

The last quality which may have a bearing on the kind of attachment Brainard’s work elicits is the sense of unity between Brainard the man, the visual artist, and the author. Besides the more evident connections between life and art, such as that between his homosexuality and the queer content and aesthetics (the recurrent motif of hearts, pansies, and butterflies) of his work, there is a subtle one – “a personality trace that remains … in both his writing and his visual art” (Berrigan 34). That trait could be subsumed under the notions of goodness, thoughtfulness, and generosity. Padgett’s loving biography Joe offers countless testimonies of Brainard’s altruism, from his teenage habit of sending valentine cards to Padgett’s parents to his impeccable politeness and kindness to doctors and nurses during the last months of his losing battle with AIDS.18 Ashbery, in a frequently quoted statement, points to niceness as the quality defining Brainard’s life and work: “Joe Brainard was one of the nicest artists I have ever known. Nice as a person and nice as an artist.” He seems to attribute it to Brainard’s self-effacing manner (“he didn’t want us to have the bother of bothering with him”) and to the “gratitude” and “pleasure” evoked by his work (1-2). Cotton links Brainard’s “niceness” with the earlier discussed “smallness” and the apparent “lack of artfulness” that characterize his output (94). Glavey borrows Ashbery’s tag to coin the term a “vanguard of nice” to denote a Brainardesque aesthetic that “draws together art and life … through a form of conciliatory reticence – an embrace of the banal, the silly, and the ostensibly trivial” (Wallflower Avant-Garde 147). While the adjective “nice” may strike one as an insipid summation of any artist and “may present a problem” (since great artists are rarely regarded as likable human beings) (Ashbery 1), it memorably asserts the unique integrity of Joe Brainard in all his incarnations – Brainard the man, the visual artist, and the writer.

Perhaps the “thing itself” which Schuyler and Brainard sought to capture and convey in their art (Kernan 41-42) – “the rose made out of a real rose,” as Schuyler calls it in “Fabergé” – in Brainard’s case was his own experience, personality, and sensibility.

Here, just for you, reader, viewer, real Joe made out of real Joe.

photograph by Pat Padgett

Courtesy of the photographer

Works Cited

Ashbery, John. “Joe Brainard.” Joe Brainard: A Retrospective, edited by Constance M. Lewallen, U of California Berkeley & Granary, 2001, pp. 5-46.

Auster, Paul. Endorsement. Granary, 2001.

---. Introduction. The Collected Writings of Joe Brainard, edited by Ron Padgett, Library of America, 2012, pp. xvii-xxviii.

Berrigan, Edmund. “Vulnerability in Joe Brainard’s Work.” Joe Brainard’s Art, edited by Yasmine Shamma, Edinburgh UP, 2019, pp. 34-38.

Brainard, Joe. “August 29th, 1967.” The Collected Writings of Joe Brainard, edited by Ron Padgett, Library of America, 2012, pp. 218-20.

---. Bolinas Journal. The Collected Writings of Joe Brainard, edited by Ron Padgett, Library of America, 2012, pp. 285-333.

---.“Diary 1969 (Continued).” The Collected Writings of Joe Brainard, edited by Ron Padgett, Library of America, 2012, pp. 239-49.

---. I Remember. Granary, 2001.

---. Interview by Anne Waldman. The Collected Writings of Joe Brainard, edited by Ron Padgett, Library of America, 2012, pp.

---. Interview by Tim Dlugos. The Collected Writings of Joe Brainard, edited by Ron Padgett, Library of America, 2012, pp. 489-508.

---.“Little-Known Facts about People.” The Collected Writings of Joe Brainard, edited by Ron Padgett, Library of America, 2012, pp. 509-22.

---. N.Y.C. Journals: 1971-1972. The Collected Writings of Joe Brainard, edited by Ron Padgett, Library of America, 2012, pp. 363-74.

---. “Washington D.C. Journal 1972.” The Collected Writings of Joe Brainard, edited by Ron Padgett, Library of America, 2012, pp. 383-88.

---. “Wednesday, July 7th, 1971.” The Collected Writings of Joe Brainard, edited by Ron Padgett, Library of America, 2012, pp. 334-52.

Chiasson, Dan. “Joe Brainard’s Odes to the Survivable Past.” The New Yorker, 20 June 2012, https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/joe-brainards-odes-to-the-survivable-past, Accessed 2 Apr. 2020.

Cotton, Jess. “Joe Brainard’s Still-Life Poetics.” Joe Brainard’s Art, edited by Yasmine Shamma, Edinburgh UP, 2019, pp. 80-100.

Cran, Rona. “‘Men with a Pair of Scissors’: Joe Brainard and John Ashbery’s Eclecticism.” Joe Brainard’s Art, edited by Yasmine Shamma, Edinburgh UP, 2019, pp. 103-26.

---. Personal interview. 16 Aug. 2019.

---. “Re: Here.” Received by Wojciech Drąg, 28 Aug. 2019.

Epstein, Andrew.“‘To the Memory of Joe Brainard’: Kent Johnson’s I Once Met.” New York School Poets*,* 20 Aug. 2015, https://newyorkschoolpoets.wordpress.com/2015/08/20/to-the-memory-of-joe-brainard-kent-johnsons-i-once-met/. Accessed 29 June 2018.

Fitch, Andrew. “Blowing up Paper Bags to Pop: Joe Brainard’s Almost-Autobiographical Assemblage.” Life Writing, vol. 6, no. 1, 2009, pp. 77-95.

Glavey, Brian. “The Friendly Way: Crafting Community in Joe Brainard’s Poetry.” Joe Brainard’s Art, edited by Yasmine Shamma, Edinburgh UP, 2019, pp. 127-45.

---. The Wallflower Avant-Garde. Oxford UP, 2012.

Kernan, Nathan. “Joe Brainard: The Madonna of the Future.” Joe Brainard’s Art, edited by Yasmine Shamma, Edinburgh UP, 2019, pp. 41-68.

Laing, Olivia. Rev. of I Remember, by Joe Brainard. The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 7 Apr. 2013, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/apr/07/joe-brainard-i-remember-review. Accessed 30 June 2018.

Lauterbach, Anne. “Joe Brainard & Nancy.” The Nancy Book, by Joe Brainard, Siglio, 2008, pp.7-24.

Lewallen, Constance M. “Acts of Generosity.” Joe Brainard: A Retrospective, edited by Constance M. Lewallen, U of California Berkeley & Granary, 2001, pp. 5-46.

Notley, Alice. “Joe, A Funny Nickname.” Joe Brainard’s Art, edited by Yasmine Shamma, Edinburgh UP, 2019, pp. 21-23.

Padgett, Ron. Joe: A Memoir of Joe Brainard. Coffee House, 2004.

Perloff, Marjorie. “Afterword: Joe Brainard’s Art.” Joe Brainard’s Art, edited by Yasmine Shamma, Edinburgh UP, 2019, pp. 248-55.

---. “Frank O’Hara and the Aesthetics of Attention.” boundary 2, vol. 4, no. 3, 1976, pp. 779-806.

Shamma, Yasmine. “Introduction: Joe Brainard’s Collage Aesthetic.” Joe Brainard’s Art, edited by Yasmine Shamma, Edinburgh UP, 2019, pp. 1-18.

Sturm, Nick. “‘Fuck Work’: The Reciprocity of Labor and Pleasure in Joe Brainard’s Writing.” Joe Brainard’s Art, edited by Yasmine Shamma, Edinburgh UP, 2019, pp. 183-99.

Weissman, Gary. “‘I Feel Like I Am Everybody’: Teaching Strategies for Reading Self and Other in Joe Brainard’s I Remember.” Reader, vol. 60, 2010, pp. 71-102.

White, Edmund. Arts and Letters. Cleis, 2004.

Footnotes

-

I would like to express my gratitude to Ron Padgett, whose feedback on the draft of this text helped me eliminate several factual errors and clarify some notions. I am also very indebted to Ron for kindly allowing me to use all the images reproduced in this article (and for his boundless generosity). I would also like to take this opportunity to thank Rona Cran for kindly answering my many queries and to Martyna Szot for her infectious enthusiasm about all things Joe. ↩

-

In my account of Brainard’s life, I have relied primarily on Ron Padgett’s Joe: A Memoir of Joe Brainard. ↩

-

Brainard notes in his diaries of the time that he was often too excited about work to fall asleep (Kernan 74). ↩

-

An analysis of the many collaborative projects undertaken by Brainard and Ashbery, as well as of their influence on each other’s work, is offered in Rona Cran’s article “‘Men with a Pair of Scissors’: Joe Brainard and John Ashbery’s Eclecticism.” ↩

-

In his article “‘Fuck Work’: The Reciprocity of Labor and Pleasure in Joe Brainard’s Writing,” Nick Sturm discusses the artist’s “career-long obsession and ambivalence with the activity and attendant anxieties of … artistic labor” (183). He examines Brainard’s conflicted attitude to work on the basis of the autobiographical Bolinas Journal, where Brainard documents his daily problems with motivation. In one entry, Brainard muses, “Don’t know if I want to work today or go to the beach with Bill. / Getting lazy about shaving. / Bill just called. It’s the beach for me. Fuck work” (Bolinas 296). ↩

-

The vast majority of Brainard’s visual works are untitled, therefore I use their descriptive titles as proposed in Constance M. Lewallen’s exhibition catalog Joe Brainard: A Retrospective. ↩

-

In his short piece “Andy Warhol: Andy Do It” (1963), Brainard repeats the statement “I like Andy Warhol” fourteen times in a row and concludes, “Andy Warhol knows what he is doing. Andy Warhol ‘does it.’ I like painters who ‘do it.’ Andy do it” (178-79). ↩

-

Padgett calls oil portraiture Brainard’s “ultimate challenge” and his “nemesis” (254). ↩

-

The importance of cigarettes to Brainard’s artistic and literary oeuvre – particularly in reference to his The Cigarette Book (1972) – is examined by his younger brother John in the essay “Smoking Joe.” ↩

-

In his travelog “Washington D.C. Journal 1972,” Brainard records his skepticism about the size of specific works in the National Gallery: “Two big paintings by David (Napoleon in his Study) and Ingres (Madame Moitessier) leave me surprisingly cold. I like the postcards of them better. When a painting doesn’t ‘need’ to be as big as it is, it sometimes bothers me” (387). ↩

-

The Friendly Way can thus be regarded as a forerunner of Graham Rawle’s collage novel Woman’s World (2005), which is composed entirely out of cut-outs of British women’s magazines from the 1950s and ’60s. ↩

-

When asked in 1977 about his favorite poet, Brainard begins by crediting O’Hara and Ashbery, but then goes on to explain that while Ashbery sometimes “sweeps [him] away,” his poetry is often “over [his] head” and makes his “mind wander off” (Brainard, Interview by Dlugos 504). ↩

-

Cran also locates a shared “desire to be serious, but a preference for being funny” and “an ability take animals seriously” (“Re: Here”). The latter is a reference to Brainard’s fascination with Elmslie’s whippet Whipporwill, which is the subject of many of Brainard’s oil paintings. ↩

-

Ann Lauterbach likens Brainard’s art into that of one of his favorite painters – Giorgio Morandi, whose works show a similar “reductive clarity” and a “gift for distillation” (11-12). ↩

-

Three paragraphs of this section use revised fragments from my article “Joe Brainard’s I Remember, Fragmentary Life Writing and the Resistance to Narrative and Identity.” ↩

-

In the endorsement, Auster called I Remember “one of the few totally original books [he has] ever read.” He also predicted that “the so-called important books of our time will be forgotten, but Joe Brainard’s modest little gem will endure,” echoing the words of Schuyler, I Remember’s first reader and supporter, who referred to it as “a great work that will last and last” (qtd. in Padgett 146). ↩

-

Andrew Fitch’s article “Blowing up Paper Bags to Pop: Joe Brainard’s Almost-Autobiographical Assemblage” examines I Remember as an example of “popography”—a life writing genre emphasizing the reliance of individual experience on the mass media. ↩

-

Padgett remembers that although they knew each other for over forty years, there was only one situation when Brainard was angry with him. Brainard expressed that in a short note, which he still signed “Love, Joe” and followed by a postscript: “Write a nice letter soon so I will not stay mad” (96). At a different point, Padgett relates that Brainard, upon hearing that a waiter in his restaurant could not afford to visit his dying friend in Australia, he spontaneously gave him several thousand dollars (264). “It is tempting,” concludes Padgett, “to think of Joe … as a kind of saint” (308). Kernan: “In the parable that was both his life and his art, Joe Brainard gave away himself” (66). ↩

Cite this article

Drąg, Wojciech. "Embraceable Joe: Notes on Joe Brainard’s Art" Electronic Book Review, 7 June 2020, https://doi.org/10.7273/42y1-2s16