Pasts and Futures of Netprov

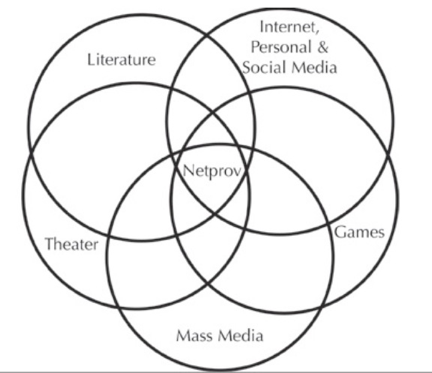

In Pasts and Futures of Netprov, Rob Wittig articlates a theory for Networked Improv Narratives, or "Netprovs." Wittig, an innovator in this novel form, situates netprov at the interesection of literature, drama, mass media, games, and new media. Transcribed from a presentation given at the Electronic Literature Organization conference in Morgantown, WV, Wittig explores a number of antecedents to the form, documents current exemplars of this practice, and invites readers to create their own networked improvisations.

Introduction by Davin Heckman, Managing Editor

In the course of cleaning out a dust-covered trunk in my attic, I stumbled across a text file with a set of instructions:

Please upload this file to the Wittimatromaton and press play at the appointed time.

Further notation indicated:

This text was transcribed and adapted from a talk given at the Electronic Literature Organization conference in Morgantown, West Virginia, June 22, 2012. Text from the slides is shown in bold.

Bundled with this file and notecard, I found a weathered sheet of paper that could barely tolerate the pressure of my trembling fingers. What the hell was I looking at? Why was it in my attic? On it was a diagram of Rob Wittig with gears and wires inside, along with a little sketch of a circuit. Wittimatraton 2012! Dust crept into my mucous membranes, sweat dripped down my lip. I sneezed, the paper broke to pieces in my hand. Frantically, I clawed at the fragments and they crumbled into dust… But I imagine I saw it.

At this point, we can visualize this failed (Apocryphal? Speculative? Fake?) automaton that more or less resembles Rob Wittig, perhaps built on the frame of a decommissioned animatronic pizza-hustling mouse. The uncanny machine grinding out the text in the best 2012 American male text-to-voice that the technicians could muster, long arms clicking and jerking towards the slides on the projector, rubbery flesh flabbering along to the words. Attendees in desks, taking notes, eating pizza, live-tweeting, nodding thoughtfully at the mention of Jane McGonigal, raising eyebrows over Spike Milligan, musing quietly for Del Close. Great Moments with Mr. Wittig!

It was among the strangest moments that did not occur at the conference. I know this because I was not there! I Skyped into my session from Norway. But you know how it is, things malfunction. Perhaps, at the last minute, I imagine, the robot had to cancel its appearance. And so Rob Wittig had to present the text in its stead. I heard that he did a very good job, though it seemed too natural for some.

I know what I had missed, because I had served as an outside reader on his thesis committee for University of Bergen. We discussed his thesis at length in a hot tub in Scotland (actually, this is sort of true). And I found myself fascinated by Netprov and the genealogy he was tapping into, the territory that scholars have neglected: old time radio, comic performance, and hoax religions. I was so fascinated, that I chased down every opportunity to step into this weird world of collaborative narrative, shared hallucinations, and performed texts. I became, still am from time to time, several characters in his Netprov world.

We think of digital media as a rich media space, beyond books, beyond radio, beyond television. And, it is. It can be. But against the backdrop of high speed internet, cheap memory, and powerful processing, a simple string of text marks out a vast open space. Between the indexical pics or it didn’t happen and the rhetorical assertion it certainly did is a wonderland of speculation. Speculation into what exists beyond the reach of the word started with our ancient ancestors’ first attempts at storytelling. Literary aficionados typically hold a special place for the novel as a textual bridge into the unknown spaces of subjectivity, but that is not necessarily the pinnacle of the literary. Even in a world in which almost everything becomes data, we find ample occasion to speculate endlessly about what exists in the pixels of panoptic digitalism that aspires to capture everything. Words, somehow, become even more provocative in an age of rich media, because in a medium built on yeses and nos they give us maybes.

Whether you believe my little yarn about animatronics is no matter. You can just pretend to believe it. But I swear that what follows is no more absurd and no less powerful, whether you pretend it is an article in a journal, a transcript of a lecture, or the instructions for animatronic performance. What matters is that you were there when it happened. And maybe you are. Because you are reading this right now: Rob Wittig’s “The Pasts and Futures of Netprov” marks an important moment in the emergence of a literary form.

---

I’d like to ask everyone to stand up. Yes, go ahead, stand up. Thanks! Now I’d like to authorize everyone to do something your moms probably discouraged you from doing; I’d like to you point at someone you don’t know. Great! Now I’d like you to go over and sit next to that person temporarily, just for a few minutes. Introduce yourselves, say ‘hi.’ We’re going to play a little netprov-style game.

I’d like the people who are sitting closer to this side of the room, where I’m standing, to perform the following thought experiment: you can time-travel to one place and time in history. Where will it be? Think about it for a moment and tell your partner.

Now I’d like the other partners — the people sitting closer to that other side of the room — to think for a moment and describe to the time traveler what you think would really happen starting from the moment they appear in that past time and place. For real. Not a convenient Hollywood version where everyone in the past speaks English and accepts women running around unaccompanied, or whatever. What really happens to your partner? Tell ‘em!

[The room fills with mirthful hubbub.]

Great! Thank you! Great!

I’m Rob Wittig and I am passionate these days about an emerging art form called netprov. I’m a long-time practitioner of electronic literature, and netprov contains basically all the elements that have most entertained me and cracked me up over the years. The time-travel game you just played contains the core elements of imaginative play and thoughtful artistry that are at the heart of netprov.

You accessed your imagination to co-create a micro-work of imaginative fiction on the spot, in the middle of a normal day at a conference. You who went first bravely created a fictional base reality and shared it with your partner. You who went second reinforced and heightened that base reality by viewing it through a lens of naturalism not typically used in the science-fiction/fantasy genre. If I judge by the laughter that swept the room I’d say that your genre-busting was used to good comic effect. Had you done all this in text messages or in Twitter you’d have been doing netprov.

Netprov is networked improv narrative. It’s a way of using existing digital media in combinations to create fake characters who pretend to do things in the real world. In other words it gets back to the original impulses of fiction. And, like the origins of many genres of fiction, many netprovs have a quality that netprov people love: they induce a moment of vertigo where people don’t quite know whether it’s real or not—“was what I’m reading written by a real person, or is it fake?”

This work that I’m presenting today is a brief version of ideas accumulated in a thesis that I did for a Master’s Degree in Digital Culture at the University of Bergen in Norway. And I want to thank Scott Rettberg, and Jill Walker Rettberg, and all the good people there in Bergen for their support during this period. I got a chance to really look at in detail at the kind of work I’ve done over the years, the kind of work I like, and to build something fun and new.

Netprovs play out in real time. The recent netprovs I’ve done — the bigger ones that I call “major netprovs” — are outlined in advance of the performance. They have a plot arc and established characters. But the details of the writing and the details of the image making are done in the moment, in real time, in an improvisational way. That’s what makes it fun and exciting to me.

Selected early netprovs

- The Unknown

- Los Wikiless

- Timespedia

- The Ballad of Work Study Seth

- Bronx Zoo’s Cobra

Within the Electronic Literature Organization canon there are some early netprovs. “The Unknown,” (Rettberg) the group project by Scott Rettberg, Dirk Stratton and William Gillespie in which they chronicled the imagined excesses of a debauched book tour in real time, is, par excellence, a kind of long form netprov. Mark Marino’s “Los Wikiless Timespedia” (Marino 2008) is another; it imagines the Los Angeles Times going completely to an online wiki format and then getting derailed. “The Ballad of Workstudy Seth,” (Marino 2009) grew out of a moment where Mark Marino’s workstudy student (fictional, of course) hijacks his Twitter account. Then there are very simple anonymous projects like the moment when a news story warns of a cobra that escaped from the Bronx Zoo and, and almost instantly a Twitter feed from Bronx Zoo’s cobra appears and the cobra’s making wry comments and going for coffee at Starbucks, and people are interacting with it, playing along. In a moment I’m going to describe a complex, major netprov. “Grace, Wit & Charm” that has developed characters, complex creative interactions with users, and even a live stage show as one component, but first I want to step back and place netprov in its broader historical and cultural context.

Qualities that define netprov

Netprov creates stories that are networked, collaborative and improvised in real time

In thinking and writing about netprov, I came up with a list of qualities that define netprov.

Netprov uses multiple media simultaneously. Transmedia

Netprov isn’t just a book or just a play or just a website. It uses basically the same complex systems of varied communication technologies that real people use in real life. Different netprov authors design projects in different ways. My own taste is to do projects based, technologically, on things that real people actually do in the real world. This idea of using multiple media to tell the same story is something that a scholar Henry Jenkins has dubbed “transmedia.” It’s the kind of thing that big Hollywood studios use to coordinate a video game, say, and a website, along with a film or a television show that they make.

Netprov is collaborative among featured players and incorporates participatory contributions from casual reader/players. Playful

Netprov is really about playing, and there are two ways in which people can play. The first is what I call netprov games, which are short creative bursts with specific assignments. They’re not unlike memes that pass around the internet. You can do one response or 100 responses during these games, but the responses are all freestanding and they don’t take a lot of complex coordination with other people. The second way to play is the major netprovs that have a core group of “featured players” who are used to creating with each other, operating in a theatrical troupe model or a design studio model. All the actor/writers are assigned characters. In my netprovs I’ll often create a preliminary character back story. The writer/actors that I’m working with these days are great at coming up with more details about their characters. Netprovs done with featured players build stories that that more resemble what we’d call a story and a novel in a film, in a play.

Netprov is experienced as performance as it is published; it is later read as a literary archive. Puzzle: single work? repeated performances?

One of the most interesting things about netprov is that it comes from a variety of different art forms. It’s got inspirations coming out of theatre, coming out of mass media in movies and broadcast, coming out of literature. We’ll talk about that a little bit more in a moment. But it means that it’s difficult to know exactly how to think about netprov projects. There’s a live performance aspect, but at the same time it leaves a trace—if you’re lucky.

(laughs)

I’ve had some technical problems in various netprovs that I’ve done; the websites have been spammed to death. But the ideal is to have a complete archive of everything that people have contributed.

So I find myself in a very interesting place these days: not knowing quite how to frame netprov to myself conceptually. For example, I did a major netprov in 2011 called “Grace, Wit & Charm.” (Wittig 2011) Should I consider it like a novel? With my Literature Hat on I could say that I planned it, and we (the ensemble) wrote it — once-and-for-all — and that the resulting record lasts for eternity as a novel. Or is it like a play? With my Theater Hat on, there is no reason that same story can’t be re-improvised, restaged, repeated an infinite number of times, with different featured players even. Or is it more like a television show? With my Mass Media Hat on we would get the same cast together, and bring them back next year, and continue the story in real time. It’s now a year later. What’s happening to those characters? It’s one of my greatest pleasures in life to be at this moment of vertigo in a new art form where you don’t quite know how to answer these questions. Is “Grace, Wit & Charm” done? Is it just beginning?

(shrugs and smiles)

During the performance, netprov projects incorporate breaking news. my election romance

One of the things that I’ve loved for a lot of years about electronic literature and being able to publish instantly is that you get to incorporate breaking news in a planned story. One of the examples of this that I’m joking around with these days is an idea for a netprov that could be done in conjunction with the Presidential election in the U.S. in the Fall 2012. You would devise a kind of Oulipo-style system for creating the texts of two lovers; one character is based on the Republican candidate, and one character is based on the Democratic candidate. These two long distance lovers can only communicate to each by doing remixes of that day’s statements from those two candidates. In other words, you, you use real-life events to kind of spinoff and remix your own story.

Netprov projects use actors to physically enact characters in images, video and live performance. hi, it’s…um…well…“me!”

One realization that turned up in the research I did at Bergen was how different netprov is from the traditional literary mode in which you write descriptions of characters and the characters appear in people’s minds. I was in a graphic design mode from the beginning of each major netprov. I used photographs of models to create characters. As the netprovs got more elaborate I was using writer/actors to portray and co-create the characters. This brings this different element to it. It’s how people create personas and self-presentation naturally on the web, but for someone with primarily a literary and graphic design background like mine it’s a bit new and unusual.

Some writer/actors enact the character they create. featured players

These days I’m really intrigued with this formula of playing with people who are both writers and actors, who basically create their own character in real time during the course of the netprov. There are a lot of projects I classify as netprovs that don’t use this writer/actor element, but it’s a characteristic of the kind of netprovs that I like and that crack me up. It’s a basic impulse that’s always been there in my creative writing: looking out in the world and seeing ridiculous, exaggerated figures, and recreating them in, hopefully, an interesting and enlightening way in character form. It’s the fundamental impulse that I’ve always had of doing voices, doing puppets, doing characters for my friends. I figure it’s going to be always a part of the netprovs that I’m involved in.

The writer/actor idea started for me maybe ten years ago in an idea for a netprov-style fiction about a struggling improv theatre company in Chicago called “The Struggling Theatre Company of Chicago,” where you could read the fictional actors’ behind-the-scenes blogs during the week and learn about all their horrifying soap opera romances and betrayals, all their jealous rants and flame wars. But then you could actually go see them live on stage every Saturday night. You’d come into the theatre already knowing a ton about these characters, their whole back story drama, but the characters didn’t know you knew. The purported show would be “bad” but it wouldn’t matter because you were interested in the actors and the back story as it leaked out.

Netprov is usually parodic and satirical “hey look @ me! i’m texting and driving like an asshole”

(Rob gestures toward screen)

Some netprov projects require writer/actors and reader/ players to travel to certain locations to seek information, perform actions and report their activities. alternate reality games

Ideas very similar to netprov are being enacted now in a realm of the gaming world — not mainstream online gaming, but a hybrid of online communication with real life activities — called alternate reality games. I find them really interesting and I’ll talk about them in a moment.

Netprov is designed for episodic and incomplete reading. hang on, i have to take this call

In the classic literary and theatre traditions, there is an assumption or a wish, a hope, that readers and audience will hang on every word in the order that it was intended. Now we know perfectly well that attention wanders for both readers and audiences, but that ideal has always haunted those practices. Well, in netprov, I’m okay with the fact that people are not going to read everything. And it definitely encourages a different kind of composition, a holographic composition where the story is constantly retold in miniature so that newcomers entering at any time are invited in.

Chicago Soul Exchange

So what’s an example of a netprov? Well, this is one that’s been in my mind for several years. I did a complete one-week version of it in 2010. It’s called “Chicago Soul Exchange.” (Wittig 2010) It’s based on the premise that there are more human beings alive now than the sum total of human beings who have ever lived before, which makes it arithmetically impossible for everyone to have a past life. So I imagined an eBay-style, on line, past-life brokerage. As I thought about it I imagined this kind of homespun, almost neighborhood-y past-life brokerage in Chicago run by a character whose screen name is Past Life Maven. And I began to imagine what would happen if she actually got an interesting, and therefore valuable, past life to sell. Because obviously, the vast majority of past lives would be, you know, “agricultural worker #324554” — fairly simple folks. The cultural meme about past lives, the cliché, is that people always imagine themselves kings, and queens, princesses and princes.

At the simpler, netprov game level, I invited casual players to do something that’s, to me, kind of funny — but funny because it’s so horrible — which is to sum up an entire human life in two sentences. Here’s a typical one someone contributed: “A young herdsman fearing blame for a plague among the sheep, this young man had the rare ambition to flee his tribe with merely his clothing and a sling. Trespass on the water holes of a rival tribe brought a swift end to his promising life.” Then on top of this kind of catalog, which was the netprov game, there was a major netprov story — co-written with my troupe of buddies in Duluth — that happened in the course of the week about some sort of Russian mafia firm that tries to take over the company because Past-Life Maven actually gets her mitts on a bona fide knight. They squabble. Hilarity ensues. Someone falls in love with her past life — hot and heavy — which precipitates all sorts of icky ethical dilemmas. And then finally there’s a huge leveraged takeover of Chicago Soul Exchange by a Belgian megabank — an allegory of the 2008 financial crisis.

Netprov: Play and Go Deep

That gives you a sense of how the fictions play out. And really the goal for me in netprov — the reason I love doing it — is that it invites a reader/player audience to play and go deep. By “going deep” I mean psychologically deep, politically deep, going to the subtle smart places that the literature of the past that we love.

As I looked at netprov, I saw that it basically comes from five different root systems and I did some research into each one.

Roots of netprov in games 1

- Mornington Crescent

- Callois: “ruled or make believe”

- Mimicry

- Mimicry with an agon coating: poetry slam

- Bernard Suits:“voluntary attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles”

The biggest learning for me was the similarity of netprov to games. I’m mostly a graphic design and literature person. Until these last few years I haven’t been much of a game person. So this was a wonderful revelation for me. It gave me occasion to really reflect on the answer I give when people ask me: “What is your favorite game?” It is a game that I’ve never really heard played, based out of a radio comedy show in England. The game is Mornington Crescent. (Brooke-Taylor) And it, it takes place using the London tube system map as its playing board. The putative goal is to start from any other station and wind up at the station called Mornington Crescent. But what happens when people begin to play is that —invariably and immediately — the game devolves into an endless argument over the rules. So it is a game, but it’s not the game that it pretends to be, and that’s what I love about it. When I think of the fiction tradition, and the satire tradition, and the comedy tradition of netprov, it’s this kinds of game that are the real ancestors of netprov.

Theorist Roger Callois classified games into two categories — either they have rules or they’re games of make-believe, mimicry, with no rules —really made a lot of sense to me. Netprov is clearly a make-believe game or a mimicry game. In Jane McGonigal’s, very interesting book Reality Is Broken (McGonigal), she quotes Bernard Suits’s definition of games as her favorite, which is “the voluntary attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles.” When I looked at this, I just couldn’t see it applying to what I was thinking of as netprov. So I came up with a kind of alternative formulation as a foundation for further theoretical thinking: netprov is the voluntary attempt to heal necessary relationships. It incorporates a social, interpersonal dimension to this kind of fiction-making.

Roots of netprov in games 2

- McGonigal: ARGs are games you play to get more out of your life as opposed to games you play to escape it

- Participation architect

- Healing insight

McGonigal defines alternate reality games (ARGs) as ways to get more out of your life and to throw you into real life rather than an escape. McGonigal descirbes a project that she helped create, “World Without Oil,” (Eklund and McGonigal) which asks players from a wide variety technical backgrounds — banking, science, humanities — to imagine together what would happen if the world suddenly ran out of oil. This seems to me like a netprov: collaborative, real-time fictionalizing about a premise. Her job title in that project was Participation Architect. She was responsible for enabling and empowering people to participate. This role was a great revelation for me, because it’s not the way artists in the Romantic Era — and make no mistake, we’re still at the end of the 200 year-long Romantic Era — are taught to think. Romantic artists simply express themselves, and people either get it or they don’t. ‘Screw them if they don’t understand’ is the archetypal romantic attitude.

This idea of really inviting and helping your reader/players to play is something that I really want to get better at myself. And the “World Without Oil” game has this characteristic of being a kind of social, political, historical corrective. I saw that this has something in common with the satirical impulse that I always felt behind netprov. Because satire is also a corrective, ultimately intended to heal.

Roots of netprov in theater

- Commedia dell’arte

- “Yes, and”

- Mimicry-Parody-Satire

- Healing insight

- Character-driven stories

The ‘prov’ in netprov comes from theatrical improv. And theatrical improv in the second half of the 20th Century in America always credits its roots as being commedia dell’arte, a wonderful form of theatre that goes all the way back to the ancient Greeks in an unbroken tradition. Commedia dell’arte was a particular Italian formulation, but the stock characters of the doctor, the captain, the, the young maiden, the young man, and so on, go way back. Commedia dell’arte had story lines that were passed down in scenarios, as they called them, but the actual lines said on stage were always improvised. And this kind of free and easy improvisation was really inspiring to theater people in the ’50s and ’60s when it combined with the beat movement and hippie movement. It modeled a liberating moment which freed one from slavishly repeating a written text.

The core principle of theatrical improv, as developed mostly in Chicago (which is the tradition I know best) is that when improvising, you never say “no” to a partner; you always say “yes, and.” By saying “yes, and” to whatever anybody else in the team says, you accept it, and you work with it, you add to it, you run with it, you never dispute it.

So in my theoretical writing I made an extension from mimicry, which is just the basic children’s game impulse, to parody, which is more elaborate imitation. And then then I extrapolated parody to satire, which has this goal of healing insight. Like the commedia dell’arte, what I saw developing in the netprov projects I was doing and interested in was the idea of being based on characters and letting characters really flower and come to life. Again it’s that puppetry impulse, that ‘doing voices’ impulse.

- Saint Close

- Compass Players> The Committee> Second City> SCTV> Saturday Night Live> Improv

- Olympics Group mind

- “Don’t try to be funny, just be real”

The theatrical improv figure that I would call to people’s attention as I look back after about six months or so now on the thesis work, is Del Close, one of the great patron saints of netprov. Del Close had a formative hand in a Who’s Who of American improv and skit comedy in the second half of the 20th Century: everything from the Committee in San Francisco, the Compass Players in Saint Louis to the Second City troupes in Chicago and Toronto, and SCTV and Saturday Night Live on television. Del Close was the mentor of generations of comedians from Alan Arkin, Bill Murray, Harold Ramis, Dan Aykroyd, Mike Meyers, right down to Tina Fey and Amy Poehler in our day (Johnson).

Del Close built a wonderful idealistic vision of what he called “group mind” — the level of artistry that the great commedia dell’arte actors had — where you are all behaving as a single organism on stage. His descriptions of it are very spiritual and psychological; it’s very moving. It’s a description of an ideal way to be a human being that I subscribe to. One of his great pieces of practical advice was that he would apparently be ruthless with his students when he saw them reaching for a joke. He encouraged them simply to be human and be real, be their character in the full struggles of life. If that was going to be funny, it would be funny on its own, you never had reach for humor.

Roots of netprov in mass media

- Transmedia

- Radio, the forgotton medium

- Vast narratives

- Technologically self-aware comedy

I’ve been very influenced by various forms of radio including the old “Goon Show,” and the stereotypical American, frenetic “Morning Zoo” format. I fear these vernacular grassroots art forms are going to be lost. In them there are a lot of inspring ideas of doing long-term character voices, using sound effects, all kinds of things.

(plays comic morning zoo sound effect)

Related to transmedia, I also really like the idea that I saw first in Noah Wardrip-Fruin’s work of what he calls “vast narratives,” which are fictional worlds that go and go. The Lord of the Rings is an example. The concept encompases TV shows such as “Doctor Who” and “Star Trek” that are extended by fan fiction — gigantic fictions that spread across media, across the decades.

Another elements that many of these root fields of netprov share technological self-awareness. My favorite example is a wonderful passage in Monty Python. When they were in the studio they shot on videotape to save money, but when they were outside they shot on more expensive film because film cameras were more portable. In one episode, there’s a character who goes outdoors and says: “I’m on film out here!” He goes back inside and walks onto the set and goes, “Look, I’m on video indoors.” Fictional characters being aware of the medium they’re in — the Tristram Shandy moment — is something I love in all art forms, and it’s a characteristic of netprov.

- Saint Milligan

- Goon Show> Beatles> Monty Python

- “little does he know that…”

There’s a second saint, from the mass media world, that I’d love to honor: Spike Milligan. He was the writer of “The Goon Show.” If you don’t know Spike Milligan, I highly encourage you to read The Goon Show Scripts (Milligan), they’re just hysterical, and the Goon Shows now are streaming 24/7 on line (Streaming Goon Show). What Americans know as the Beatles’ sense of humor and the Monty Python sense of humor, all that comes all straight from Spike Milligan. He had so many wonderful little tropes. On “The Goon Show” a character in a dialogue scene will say “Little does he know that I’m hiding up my sleeve this, that and the other.” Then the other character will respond directly, “But little does he know that blah, blah, blah.” It’s a wonderful moment of characters hearing each other’s secret asides to the audience, breaking the rule, violating the convention; it’s the Mornington Crescent gesture again.

Roots of netprov in literature

- WASH ME

- “Boo!”

- Robinson Crusoe written by himself

- Fictionalized vernacular

- Facsimile graphic design

- Surrealism

- Oulipo

- Invisible Seattle

In my original home turf of literature that there are many roots of netprov, especially places where the materiality of the communication is called into question by the content. One of the ancient, basic jokes of writing is to take your finger and write on the window of a dusty car the words “wash me.” The car is doing something that only human beings can do; the car is speaking. And at some level our minds answer the car’s mute plea, even by ignoring it. It reminds me of what I want on my, carved on my headstone, which is “Boo!”

The novel is now a mature, some would say decadent, art form. But there were moments in the novel’s early days where readers experienced the same kind of vertigo I love in netprov: they didn’t know if the characters, the story, were real or not. Remember that the title page of Robinson Crusoe, if you look at the facsimile title page, it does not have Daniel Defoe’s name on it; it claims the adventures of Robinson Crusoe were written by Crusoe himself. There is a long tradition within literature of taking everyday ways of writing and telling the truth and lying in them, and fictionalizing them. And that primal gesture has always appealed to me.

Among my own stylistic and formal loves are surrealism and the Oulipo. The Oulipo is the Paris-based group of writers and mathematicians dedicated to developing mathematical systems for literature. Their favorite example is the sonnet, which is a logical mathematical system in language. I’m heartened by their insistence on the materiality of language as opposed to the prevalent assumption that language is a transparent container for content. And my own personal background in electronic literature begins with this group Invisible Seattle, and The Novel of Seattle by Seattle (Invisible Seattle), the amazing process of coaxing the city into writing its own great novel about itself. I wrote about these early online literary exploits that unfolded in the decade before the web in the book Invisible Rendezvous (Wittig).

Roots of netprov in internet, social media, personal media

- Web frauds and fictions

- Networked performance of identity

- Tweet Too Hard

- Blue Company

What does the mimicry of netprov mimic? Mostly internet, social media, and personal media forms. There’s a whole world of degrees of fictionizing on the web—from outright frauds, to fictions that people want to be taken for real. When you really slice it thinly, there’s all kinds of different flavors of lying essentially, fictionizing. A lot has been written already about the way in which identity is constructed through images, through written locution, through vocabulary, and that kind of thing. There are also lots of examples of games, very similar to netprov games, being played on the web. One of my favorites is a website called “Tweet Too Hard” which invents self-important, fatuous parody tweets, writers trying to outdo each other in being self-important. “My other BMW is at the shop today.” “Already 12,000 hits on my new lecture. Hmm, I guess it must be connecting with people.” Then in my own electronic literature experiments I wrote Blue Company (Wittig 2002), a novel in email that had some netprov elements: it was a real time experience over the course of the month as the readers got their emails, it included current events.

- Laughter

- Insight

- Empathy

I have a great fondness for everyday interpersonal communication, for love letters if you will, and I love fiction that impersonates real people in real settings. At the moment you, the reader, realize it’s fiction, there’s a spark, you start cracking up, you start to learn things about real life. And ultimately, I hope, this moment of insight helps of understanding and bringing some kindness to other people’s experience.

Grace, Wit & Charm

The art form I’m seeing includes small-scale netprov games — such as the one you played with your partner earlier — that become building blocks of larger, major netprovs with featured players. I want to describe the big project I did in my master’s work at Bergen, “Grace, Wit & Charm.”

How I see the major netprov structure is: at the core, the lead writer/director, and then the featured player writer/actor troupe and the graphic designer and the programmer. Visual and verbal elements work hand-in-hand from the beginning. These are surrounded by the casual players playing the building-block games, and then there is a pure audience/readership of people who read and watch but don’t play.

The projects I’m imagining now — this is fair warning — might start very thin and light, seeming like a one-character, ephemeral idea like Bronx Zoo’s Cobra. Then all of a sudden one day there’s a link that leads to this very elaborate, beautiful, rich website with amazing characters — elaborate, illusionistic material that’s been created painstakingly for a year or more. A whole fictional world opens up like a trap door.

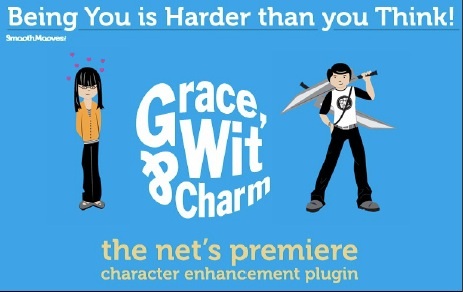

“Grace, Wit & Charm” is about an imaginary company that helps you present yourself online. The product “Grace” helps your onscreen avatar move more naturalistically, no matter what game or 3-D environment you’re in. “Wit” is for people with no sense of humor who want to leave funny status updates and banter in Twitter. And “Charm” is a product for the romantically impaired; it helps clients flirt and conduct online relationships.

The promotion for the project in the period before the two-week performance was like this, and was trying to echo, in its graphic design, a sense of a kind of youthful game culture and social media world. The promotional materials invited people to an open house where they were going to actually get to see a team of character enhancement agents from the parent company Smooth MovesTM, the people that actually bring the products Grace, Wit, and Charm to life. So on the fateful day when these unsuspecting workers work lives were going to be made public, you found these folks.

(laughter)

This is the team: Deb, Neil, Laura, and Sonny. They have been working seven days a week for many months in the unglamorous rust belt of America, not the Silicon Valley. The company’s response to the economic crisis was, of course, to downsize and ruralize the workforce and upsize the hourly requirements. The open house finds these four characters in a bitter struggle with the Shreveport call center for the vacation, because only one team from out the whole global company is going to actually get a vacation in the next few months. And they have to do it by solving the most client problems.

Of course the characters were from the group of writer/actor buddies that I hang out with. One of the initial impulses for the whole project was a moment where — as I’m sure you’ve all done many times — I was prancing around my living room imitating a World of Warcraft character and that bizarre kind of artificial gait that you see from behind as your World of Warcraft avatar lopes across the field.

(Rob prances; laughter)

When I stopped loping I went into kind of a more regular, naturalistic body movement. And I went, wow, what if the avatar would do that? What if the avatar suddenly smoothed out and began to move very naturalistically? That idea combined with this other core image of a workgroup that’s there at any time of day or night waiting to service online clients. They’re moping around in their motion capture suits, drinking coffee, chitchatting, text messaging. And then all of a sudden, the alarm rings, and a character like Deb here has to leap up and fight a dragon.

And so she grabs the toilet plunger, which was the universal prop for just about everything, and begins solving problems for the client.

Essentially, “Grace, Wit and Charm” is the back-channel, behind the scenes Twitter feed that ties these characters together. They’re talking with each other as they’re working sharing about their, their lives. And it becomes clear that besides this competition for the vacation, there are a number of other subplots, each character has a subplot. Neil’s wife is a soldier stationed in Afghanistan, and it turns out that she’s cheating on him. And Deb’s kids are getting addicted to video games. Laura has a bad boyfriend. Sonny’s competing soon in the radio-controlled-model-snowmobile Grand Nationals. And one of the details that I loved was — just as would happen with a struggling company and a struggling economy — when you to buy the products on the website they’re temporarily out of stock.

Ladies and gentlemen, please keep your cell phones turned ON throughout the performance

Even though most of the story was carried in Twitter, for “Grace, Wit and Charm” we actually had two nights of live theater at Teatro Zuccone in Duluth. When you came on Tuesday nights to see the characters come to life, they were right in the place in the story they were in real time. I got to make this announcement telling people to use their phones during the show, which I’ve always wanted to be able to make.

People in the audience, and people watching on a live stream, were Tweeting challenges to the team. I outlined the plot so that some crucial things happen during the liver performances. There’s a kind of romantic crisis and resolution among the team members that gets resolved during the first live show.

But one of the things that intrigued me and became the plot theme of the second live show was the bizarre healthcare situation in the US. I imagined that one of the things that a real company like this would be employed for was to begin doing long-distanced healthcare in a way that’s going to be cost-effective for the healthcare industry. The character Sonny, who we know from a lot of the back chatter, is a passionate hobbyist of radio-controlled model snowmobiles, and has very fine hand skills from repairing these little snowmobiles and snowmobile engines. And here he is performing a surgery, being coached by Deb, in the motion capture zone of the stage for the client VirtueCare.

Deb is very excited about it, she loves science and spent some time in veterinary school. Sonny is kind of reluctant, but Sonny’s got the good hand skills, so Deb and Sonny have to team up for these surgeries. By the end of that second show, there was going to be a carpal tunnel surgery, an actual real surgery that they were going to do by long distance. Well, it turns out that Neil, one of the characters, because of his work for Grace, Wit and Charm has also gotten carpal tunnel disease. And since the company doesn’t provide healthcare, he has no way to pay for surgery. So the, he gets an on-stage carpal tunnel surgery from Laura as she imitates Sonny and Deb’s, the tele-surgery. This is Neil stoked to gills on horse tranquilizers getting his onstage surgery in a pillowcase, with the spooky VirtuCare logo looking on.

By the end of this netprov’s two-week run most of the fictional team’s work has migrated away from being game-based avatar-based work toward this healthcare work. What the team is doing by the last few days is doing a lot of hospice care, and actually helping people through their last moments of life. And so the very last Tweets of this first performance of “Grace, Wit & Charm” consist of the team getting together to help a woman client ease into death. The last line is, “I think that’s it,” which ends both the project and the client’s world.

“Grace, Wit & Charm” has the shape that I always love in fiction work: something that starts out light and funny and then once you get people hooked on the characters, the bottom drops out and it gets serious. Once you’ve bonded with the characters, you can go into areas that are deeper.

Come and play netprov. Make netprovs! It’s an open invitation, something I’m very excited about. I utterly invite people to contact me if you’re doing similar projects, or if you want to play in our major netprovs. I just think it’s a wonderful thing for everyone to be able to play and go deep.

Works Cited

Brooke-Taylor, Tim, et al. The Little Book of Mornington Crescent. London: Orion, 2001. Print.

Eklund, Ken and McGonigal, Jane et. al. World without Oil. 2007. Game. A massively collaborative imagining of the first 32 weeks of a global oil crisis. Independent Television Service. .

Invisible Seattle. Invisible Seattle: The Novel of Seattle, by Seattle. Seattle: Function Industries Press. 1987.

Johnson, Kim. The Funniest One in the Room: The Lives and Legends of Del Close. Chicago, Ill.: Chicago Review Press, 2008. Print.

Marino, Mark. “The Ballad of Workstudy Seth.” 2009. Bunk Magazine. .

---. “The Los Wikiless Timespedia”. 2008. Ed. Marino, Mark. Bunk Magazine. .

McGonigal, Jane. Reality Is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World. New York: Penguin Press, 2011. Print.

Milligan, Spike. The Goon Show Scripts. London: Sphere, 1973. Print.

Rettberg, Scott, et al. “The Unknown, the Great American Hypertext Novel”. 1998- present. .

Streaming Goon Show. http://goons.fabcat.org/

Wittig, Rob, and IN.S.OMNIA (Computer bulletin board). Invisible Rendezvous: Connection and Collaboration in the New Landscape of Electronic Writing. Middletown, Conn. Hanover NH: Wesleyan University Press; University Press of New England, 1994. Print.

Wittig, Rob. “Blue Company”. 2002. Tank20.

–––. Chicago Soul Exchange. 2010. Web archive. http://robwit.net/?project=chicago-soul-exchange.

___. Grace, Wit & Charm. 2011. Web archive. http://robwit.net/?project=grace-wit-charm

Cite this article

Wittig, Rob. "Pasts and Futures of Netprov" Electronic Book Review, 1 November 2015, https://electronicbookreview.com/publications/pasts-and-futures-of-netprov/