Platforms,Tools and the Vernacular Imaginary

After having lived through three generations of electronic literature, and having experienced pre-web, web, and post-web literary periods, Will Luers takes a step back and advocates an "independent digital culture" in which literary artists might explore "a reality between language and the ineffable (be it artistic, religious or secular)." A mixture of technics and magics, we may be approaching a fourth generation of e-lit that is closer to pre-industrial folklore than it is to our present, technically managed space for individual and collective "creativity."

Vernacular digital expression is the flux of signs that make up everyday networked life: the memes, selfies, bots, loops, emojis, profiles, webcam backgrounds, email signatures and everything else. Unlike what was once called “folk art” in pre-digital cultures, vernacular digital culture will always be intimately connected with the technology companies and network infrastructure that allow digital communication to occur. The types of platforms and tools determine the types of computational and multimedia writing that takes place. “Vernacular” is appropriated here as a more generic term for the delocalized forms of everyday internet expression. In his 1981 Shadow Work, the countercultural Catholic Priest Ivan Illich seeks to “resuscitate” the word vernacular to describe a diminishing area of human life:

“We need a simple, straightforward word to designate the activities of people when they are not motivated by thoughts of exchange, a word that denotes autonomous, non-market related actions through which people satisfy everyday needs — the actions that by their very nature escape bureaucratic control, satisfying needs to which, in the very process, they give specific shape” (72).

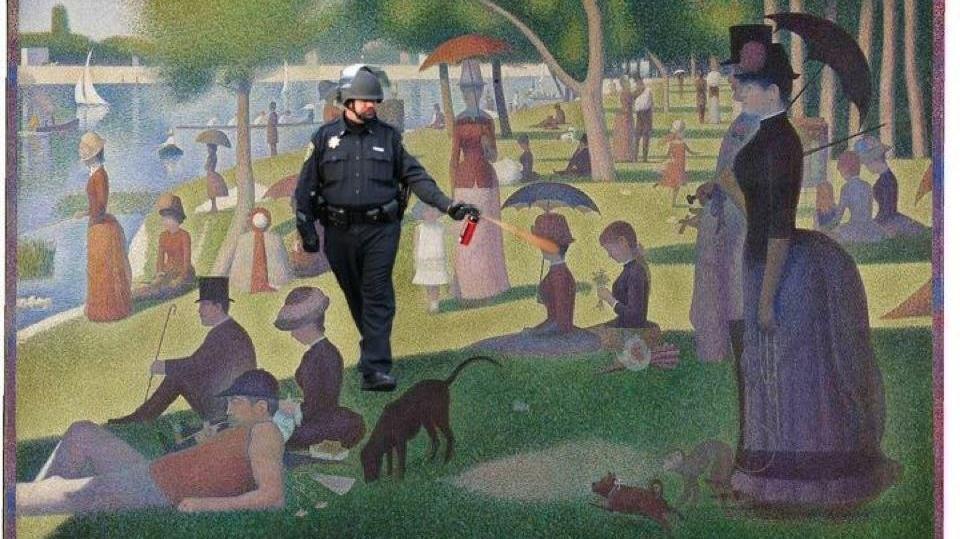

At one time this unofficial cultural domain that escapes “bureaucratic control” was called “the folk.” Can there even be something like a “digital folk” that remains tethered to the hardware, software, platforms, tools and technological practices of global networks? Folklore is a term that defines types of human expression that are outside domains of commercial, public and religious institutions. Free from dominant or official standards, folk expression is often constrained by the ideas and forms of a particular tradition or community. Trevor J. Blank, a folklorist who has edited three books on digital folklore studies, writes that it is increasingly difficult for scholars to identify authentic digital folk expression, because the “[p]erpetual, exponential growth of Internet and new media technologies leave hybridized folklore and folk culture in a constant, exhausting state of flux*” (2014, 8).* Blank observes that digital memes “display the hallmark characteristics of repetition and variation” (29) found in non-digital folk artifacts. His example of the “Casually Pepper Spray everything cop” Twitter meme, based on the controversial photo of a police officer during the 2011 Occupy Wall Street protests, does exhibit the traits of repetition and variation, as do most Internet memes. What is missing and difficult to study is the role of “community” in such acts of expression.

While there are still small online communities that share rituals of participatory creativity in some obscurity, the massive network effects of social media platforms are clearly more effective at promoting individual creative work. Most YouTubers do not become nor want to become viral superstars. That some do become wealthy and famous perpetuates a myth that in turn guides the expressive forms, and the technological biases and financial incentives pushing those forms, towards the metrics of popularity. As Walter Benjamin predicted about electronic media in the 20th Century, 21st century digital media offers the individual precisely the platforms and tools to communicate outside traditions and locales.1 “The folk” is, after all, a 19th century term for what was already disappearing in the industrial age. The study of a living folklore in the digital age therefore becomes increasingly precarious. As the folklorist Dan Be-Amos writes:

“If the initial assumption of folklore research is based on the disappearance of its subject matter, there is no way to prevent the science from following the same road”(12).

The near disappearance of a digital folk and the consequent growth of a uniform, technically managed space for individual “creativity” is what feeds both the utopian and dystopian myths of the internet.

Net artist and researcher Olia Lialina refers to the early web attempts at personal HTML expression as “digital folklore.” In the 1990s, the web was the platform and HTML was the tool. What these network technologies could or would create was undefined. A newly acquired homepage was a blank canvas or journal. Vernacular by default, the early web was made of half-finished homepages, alien looking code, broken links and error messages. It was also a period of creative possibilities and utopian dreams for free personal expression in networked groups. With few large hubs to connect people, islands of communities formed around trying to figure out what the web might be. Lialina’s own innovative digital art, as with the “net art” movement in general, was made in the context of this emerging web folk culture. She writes:

“…although I consider myself to be an early adopter–I came late enough to enjoy and prosper from the ‘benefits of civilization’. There was a pre-existing environment; a structural, visual and acoustic culture you could play around with, a culture you could break. There was a world of options and one of the options was to be different.”

Lialina’s curation and framing of the early web as digital folklore makes evident the loss of a vibrant amateur web expression on today’s platforms. Social media interfaces professionalize the vernacular and impose systems of uniform design and algorithmic valuation. The result is perhaps a less jarring and more functional web experience, but at the expense of emergent forms and communities around those forms.

Material expression online is certainly woven with the beliefs, symbols and stories offline, but the unique affordances of the computer give rise to an emergent digital imaginary or shared non-sensuous framework for the networked imagination to play in. The digital vernacular is vast, but can only know itself through ongoing self-reflective creative expression. Digital expression–as art or vernacular communication–is the process by which a medium reveals its own digital imaginary; how its set of technical methods and affordances generate new subjects, stories, myths and archetypes. The notion of the imaginary, according to Kathleen Lennon, “may be broadly characterized as the affectively laden patterns/images/forms, by means of which we experience the world, other people and ourselves”(1). In his book The Digital Imaginary, Roderick Coover brings together a variety of voices, mostly creators of digital art and electronic literature, to discuss how “computers are transforming ways of imagining the world and making stories about it.” The digital imaginary emerges, he writes, out of the “gaps between human cognition and its digital manifestations.” Many works of digital fiction do not follow an easy path in the construction of an imagined world. Samantha Gorman, the author of Pry interviewed in Coover’s book, gets at the complexity of writing a story for an exploratory interface:

“In one of the first chapters you have the character experiencing sleep paralysis. The action is internal. In addition to that you have a third, buried space. It’s a floating dream space that draws on automatic writing techniques. I try to get into that mind space, however I’m very conscious at the same time. It’s writing with a split consciousness because I have to be lost in the mind space while mentally cataloguing the ways that I’m going to tie the protagonist’s thoughts back in later to another looping structure” (61).

Mental processes are arranged as parallel story fragments, loops, navigation metaphors, cinematic montage and interface abstractions. A large part of a digital imaginary, first explored by early hypertext and net artists, is around this shared experience of interacting with a multiplicity of sign and sign-systems on a screen. Pry’s digital imaginary, the interaction metaphors of prying, pinching and tapping to reveal fragments of a lost self, mirrors the way we navigate our own lives through our devices. The work draws from and reflects back our vernacular digital language in the form of haptic gestures. Innovative art does not need the vernacular, but it is from the rich soil of everyday expression that novel forms emerge.

Exploring a new medium’s potential imaginary necessitates pushing technical and aesthetic boundaries. Much of the earliest digital innovation happened inside funded research labs where the computers were available and experimentation was encouraged. The role of public funding of the computer revolution is well-documented in the 1999 report “Funding a Revolution.” Starting in the 1940s and through the 1990s, funding from the government and the private sector went primarily to university research labs (2). The university system provided the conditions to create the Internet, the personal computer revolution and social media platforms. It continues to support, in the 21st century, the scientists, engineers, designers and artists who go on to build and design the platforms, tools and objects of digital culture. Today’s vernacular digital imaginary is therefore a result of this top-down chain of technical research, tinkering, innovation, design, development and production. But the utopic ideals of bringing digital expression to the masses has spread some dystopic results. Instead of growing unique communities of cyberculture that reinvent patterns of online living, vernacular digital expression has settled on an ordered mimicry that is wide open to algorithmic exploitation. The digital imaginary, it turns out, is a potentially murky realm between the actual and the virtual. Its seductive parade of archetypes is dangerous for some, not by making the virtual actual, but by erasing the actual altogether. We know digital addictions can destroy lives, but we seem unable to collectively change how these addictions continue to be engineered for profit by both the platforms themselves and outside entities manipulating the platforms. An extreme example of a manufactured digital imaginary, QAnon2 exploits vulnerabilities already in the public imagination (the fear of state power) and uses the technical affordances of popular platforms and tools to spread reality-erasing messages. Of course, there is also an abundance of novelty and aesthetic delight on these same platforms, but the conditions of squeezing vernacular expression into algorithmically curated, conveyor-belts of “content” do not favor artistic vision and experimentation.

How to distinguish between creative expression that is of a purely vernacular nature and works of digital art that are presented on social media? Both forms seek attention, often using the same techniques, through multimodal novelty. Perhaps because of this, Leo Flores, Kathi Berens and others have championed a greater inclusivity of popular digital expression in academic discourse. Discussions about “Third-generation e-lit,” expressive digital writing that has emerged on popular social media platforms, revolve primarily around the democratization of aesthetic value. Berens writes:

“…can a literary work be e-lit if it’s not self-consciously engaged in the aesthetic of difficulty that characterizes e-literature’s first and second generations?”

Her answer is that popular forms of creative digital writing and art proliferate on social media platforms whether this is recognized by the academy or not. Flores argues that third-generation digital creators, unlike first and second-generation, are those “exploring existing forms, established platforms, and interfaces” and are not necessarily conversant in the avant-garde practices that are celebrated in the art world and the academy. Flores’s example of the viral video “Lazy Cat“ by TXT Stories (2018), while created by a media company to promote a platform-friendly tool for creative expression, does illustrate his point that novel forms proliferate on these platforms and that their popularity as platforms should not automatically exclude them from consideration as sites of electronic literature. While the cat/human text exchange is just an extended one-line joke, its form uses the familiar interface of text messaging which points to a vernacular digital imaginary. Who exactly are we texting to and what are they doing at the moment we are texting? The work’s interface mimics scrolling, thought pauses, simulated sounds of typing and message delivery; it is a time-based, multimodal representation of a common embodied semiotic experience. As Flores points out, award-winning second-generation artist Alan Bigelow makes a similar formal gesture with his How to Rob a Bank (2016). He uses a familiar first-person perspective on mobile interfaces to narrate a story of frantic networked desire. While Bigelow’s work came before the TXT Stories web series, it draws on common network forms. There is a crossover in the digital imaginary from vernacular creator to the artist and back.

A greater inclusivity will make creators and academics see an important synergy between ambitious digital art and popular vernacular forms, but hopefully not to the diminishment of the former. Unlike the third-generation, previous generations of digital creators did not have anything established to build on. Every new work was inherently difficult and required user instructions because the computers made possible objects that did not look like any previous art form. Nick Montfort reframes the generational debate by offering his own labels that emphasize the technological substrate of digital expression: pre-web, web and post-web. For the pre-web and web periods, modernist literary practices–combinatorics, collage, montage, constraint, concrete poetry, and chance operations –opened up creative paths with computation that mainstream print, film and video did not offer. This body of pre-web and web art was the start of new rituals of participatory digital creation in a truly native digital imaginary; one that mirrors the expansive, disorienting and sometimes dysfunctional states of living with computers. Post-web digital expression, such as third-generation e-lit, is built within the ecosystems of big social media platforms whose aim is to expand reach and hold attention on creative work. What is lost when the metrics of popularity, of follows and likes, filters out the difficult or challenging works?

Critiques of third-generation e-lit are often directed at the most popular platforms that determine and promote cultural value through metrics alone. Rui Torres and Eugenio Tissleli, in their “Defense of the Difficult,” warn of a too-easy acceptance of this nonhuman “numerization of human languages.” They cite Federico Campagna’s book Technic and Magic, with its critique of the “absolute instrumentality” of Technic, the essence and world-building force of technology in which “everything is a means to an end.” According to Campagna’s schema, our technological advancements have allowed human culture to cede to the language of systems with their emphasis on measure, unit and abstract entities. This has left a “paralysis of imagination” and a “radical unreality” (Campagna, 99). Torres and Tisseli see this encroachment of Technic on arts and culture as a destructive force and something to resist. Defending the difficult in digital art and writing against artificially-generated popular forms, they suggest:

“E-literature should perhaps insist on critical digital literacies, placing the reader in situations of loss, unsettling, making foundations falter, turning our relationship with languages into crisis.”

The “difficulty” is here proposed as an acknowledgement of Technic’s failure to adequately translate those aspects of experience that escape the abstractions of computation. Torres and Tisseli imply that this failure (and consequent human loss) must be included in any digital imaginary or mythos built on top of a technological infrastructure. But there are other approaches to challenging Technic within its own regime. Campagna proposes an alternative and very old reality-system that proceeds from the ineffable rather than from absolute certainty: Magic. Magic is a symbolic language that “in no way attempts to fully convey and exhaust the object of its signification”(118). Campagna’s Magic is not the one of trickery or sorcery or dark arts, though that sort of computational sleight-of-hand is employed to capture personal data on social media platforms. He proposes a Magic that restores the ineffable within language through the use of symbol, paradox and dynamic process; an acknowledgement of forces outside the domain of Technic. The digital imaginary, as either vernacular expression or artistic innovation, is where the forces of these two systems, Magic and Technic, play out in networked life.

Anna Nacher, in her Gardening E-literature, summons an image (a symbol) for a practical approach to the issues of inclusivity and integrity in the face of Technic: the wild garden. Permaculture is the practice of allowing natural processes to unfold in the healthy growth of plants. Instead of killing off what appears at first to be pests and weeds, the gardener allows a variety of organisms to flourish, turning enemies into “unexpected allies.” Nacher suggests “the full embrace of the web vernacular, which seems perfectly fit to fill the position of an unexpected ally in striving for a rich, diverse and resilient ecosystem” will contribute to a digital imaginary that is “healthier, more resilient and more fun.” Campagna proposes a similar metaphor for how human culture can stay in balance with a technical regime. In Renaissance Italy, it was common for homes to have a garden for both food and contemplation, a miniature cosmos that was part fruit and vegetable farm, part rational geometric design and “a final part, the bosco, which was left in a state of wilderness, dotted by statues of pagan gods” (176). Making space for wildness in man-made environments, is an effective, even rational, method for maintaining healthy ecosystems. For a healthy digital imaginary, we should welcome and seek out the ineffable wildness (the Magic) in human meaning-making. Platforms, companies, universities, schools and arts organizations should also encourage an informed abandon in digital creation. In the spirit of prototyping digital culture, failures and mistakes should be embraced.

Within these discussions about vernacular, third-generation, post-web digital creativity there is the haunting sense of a loss. There is the loss of the deeper roots of human culture because vernacular sign-making is now simultaneously mimicking the dominant culture industry and dissociating from its connection to embodied networks. There is also the loss of a critical distance from a dominant culture that makes little room for challenging, visionary, minor, odd and broken forms of digital expression. Popular culture is often a repackaging of past folk culture sentiments, tapping into the longing for authentic human communities tied to a land and a history. It is now clear that a digital vernacular imaginary, manipulated by such sentiments and longings, has the potential of veering into racist, misogynist and nationalist beliefs. But only if it is dominated by Technic. An independent digital culture exploring a reality between language and the ineffable (be it artistic, religious or secular) and convening outside the dominant platforms, can also enrich the culture at large by making room for paradox, nuance, complexity, mystery and the liminal in daily networked life. The fourth-generation of e-lit may very well be working with AI. Let us hope that artists and the folk have the freedom and access to use AI to counter Technic’s own monstrous tendencies.

Works Cited:

Benjamin, Walter. The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility, and Other Writings on Media. Edited by Michael W. Jennings et al., Illustrated edition, Belknap Press: An Imprint of Harvard University Press, 2008.

Berens, Kathi Inman. “E-Lit’s #1 Hit: Is Instagram Poetry E-literature?”, Electronic Book Review, April 7, 2019, https://doi.org/10.7273/9sz6-nj80.

Blank, Trevor J., editor. Folk Culture in the Digital Age: The Emergent Dynamics of Human Interaction. 1st edition, Utah State University Press, 2012.

---. Toward a Conceptual Framework for the Study of Folklore and the Internet. 1st edition, Utah State University Press, 2014.

Campagna, Federico, and Timothy Morton. Technic and Magic: The Reconstruction of Reality. Bloomsbury Academic, 2018.

Coover, Roderick, editor. The Digital Imaginary: Literature and Cinema of the Database. Bloomsbury Academic, 2021.

Council, National Research, et al. Funding a Revolution: Government Support for Computing Research. National Academies Press, 1999.

Flores, Leonardo. “Third Generation Electronic Literature”, Electronic Book Review, April 7, 2019, https://doi.org/10.7273/axyj-3574.

Gormanm, Samantha and Danny Cannizzaro. “PRY.” App Store, https://apps.apple.com/us/app/pry/id846195114. Accessed 11 Mar. 2020.

Illich, Ivan. Shadow Work. Marion Boyars, 1981.

LaFrance, Adrienne. “The Prophecies of Q.” The Atlantic, 14 May 2020, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2020/06/qanon-nothing-can-stop-what-is-coming/610567/.

Lennon, Kathleen. Imagination and the Imaginary. 1st edition, Routledge, 2015.

Lialina, Olia and Dragan Espenschied, editors. Digital folklore. Merz & Solitude, 2009. https://digitalfolklore.org/

Lialina, Olia. A Vernacular Web. Indigenous and Barbarians. http://art.teleportacia.org/observation/vernacular/. Accessed 27 May 2021.

Nacher, Anna. “Gardening E-literature (or, how to effectively plant the seeds for future investigations on electronic literature)”, Electronic Book Review, July 5, 2020, https://doi.org/10.7273/zsyj-wm58.

Torres, Rui and Eugenio Tisselli. “In Defense of the Difficult”, Electronic Book Review, May 3, 2020, https://doi.org/10.7273/y2vs-1949.

Txtstories. “Lazy Cat. “2018. https://www.facebook.com/txtstories/videos/234390640463135/.

Footnotes

-

“It might be stated as a general formula that the technology of reproduction detaches the reproduced object from the sphere of tradition. By replicating the work many times over, it substitutes a mass existence for a unique existence. And in permitting the reproduction to reach the recipient in his or her own situation, it actualizes that which is reproduced” (Benjamin, 22). ↩

-

QAnon, classified by the FBI as a terrorist group, is a global belief system formed around the anonymous postings of the mysterious figure “Q” on the right-wing platform 4chan. “QAnon does not possess a physical location, but it has an infrastructure, a literature, a growing body of adherents, and a great deal of merchandising…. it has the ambiguity and adaptability to sustain a movement of this kind over time” (LaFrance). ↩

Cite this article

Luers, Will. "Platforms,Tools and the Vernacular Imaginary" Electronic Book Review, 1 May 2022, https://doi.org/10.7273/8jz6-ve24