Riderly waves of networked textual improvisation: an interview with Mark Marino, Catherine Podeszwa, Joellyn Rock, and Rob Wittig.

Anna Nacher chats with Mark Marino, Cathy Podeszwa, Joellyn Rock, and Rob Wittig—artists, designers, and new media theorists all—to discuss the impetus and impact of their long-running netprov collaborations (communal and improvisational creative writing conducted online). Interview conducted October 2022.

According to Rob Wittig, a netprov can be (among other things) “a simple structure—a trellis—on which you and your friends could grow your own real literature in the flow of everyday life” (Wittig 1). I have always been fascinated with netprovs, even though participation was not always easy or straightforward considering all the barriers. Some of them are quite obvious, like a heavy load of a full academic job or insecurities of a speaker using English as a second language. Yet, the improvised and playful nature of netprov makes it a perfect exercise in creative writing (or, more broadly, creative use of language). Not only that; metaphorically speaking, netprov could be considered an instance of a zoological phenomenon called murmuration, when the flock of starlings synchronizes its movements creating visually stunning shows in the skies. Just when I was conducting an extensive interview with the core members of netprov’s design team, a completely unscripted phenomenon of this kind was unfolding, mostly in Polish and Czech Twitter. That is the reason why I am providing a short glimpse into the phenomenon of #Kralovec, to better explain the moments in our interview, when we are alluding to synchronized but unorchestrated and unscripted movements of communal imagination. The #Kralovec murmuration certainly deserves more scholarly attention in the future.

-Anna Nacher

Anna Nacher

I’m really glad you were able to join, and I’m really grateful for your willingness to chat today. Basically, my idea is to present netprov as a form that exceeds the usual boundaries of genre or even literary form. I would also like to hear your own stories behind being major netprov collaborators and netprov figures. Of course, Rob has written a whole book about it. So I will ask you, Rob, to find somehow a synthetic and concise way to share also your story, even though we know more about it. By the way, the book is awesome, and I hope to have it reviewed for EBR at some point. I would like to ask you to share your own ways into netprov. How did it start for you? What was so attractive to you that you decided to get involved?

Cathy Podeszwa

I was just going to say I have a background in theater, just kind of straight up theater. And I just remember thinking that I didn’t want to do anything that wasn’t weird anymore. The netprov was weird, and Joellyn’s project was weird. That was I think the first thing I got involved with was the Mysteries Project, which wasn’t necessarily netprov, but it was more live action and movie. It was improvisation. I was at a point where I was just like, I don’t want to do straight theater, I don’t want to memorize lines. I don’t want to do anything like that. I just want to do weird stuff. And then Grace, Wit & Charm was really strange.

Rob Wittig

Cathy is also a writer.

Cathy Podeszwa

Yeah.

Rob Wittig

Very good and experienced writer.

Joellyn Rock

Rob and I met back in the 1980s. He was involved in Invisible Seattle, a group that was doing really experimental things with literature. And there was one point in 1987 or 88 when he helped bring some of the Oulipo members from Paris to Seattle where I was living, and we collaborated on an event called Constitutions Unlimited. I was in charge of organizing all the visual artists to work on that project. Rob and Philip Wohlstetter were hosting Jacques Roubaud and Harry Mathews… a small group of Oulipo who were collaborating with Invisible Seattle. And I gathered these visual artists because we were making improvisational Constitution documents that were like Dada collages, or visual manifestos, out of the writing that they were doing improvisationally, using Oulipo constraints. You must have been using Oulipo constraints, weren’t you, Rob?

Rob Wittig

Yes.

Joellyn Rock

That was my first taste of collaborating with these literary ideas, holding down the fort with the visualization of something. And so that’s a role I’ve played. To jump ahead several decades into when Rob started calling his work netprov: behind me [on the zoom background] are some Grace, Wit & Charm visuals that were part of projections behind the actors during its staged version. So getting into it was like, well, I’m always open for weird art stuff, but I also love collaborating with writers, and I’m a little bit of a writer myself, so I like to go back and forth over that division between the verbal and visual. And it’s especially fun to get to go wild with the visuals while people are being super inventive with language. Does that answer the question?

Anna Nacher

Yeah. Thank you. I mean I’m just interested in your stories.

Joellyn Rock

And I would say, like Cathy, I did some theater in my past. I’ve written plays, and I’ve done visuals for plays. Not a performance artist per se, but I like the immediacy and the surprises that happen in live theater. And I think netprov captures some of that feeling, you know—you’re not always sure how it’s going to roll out. And that adds a sort of little tension to it.

Mark Marino

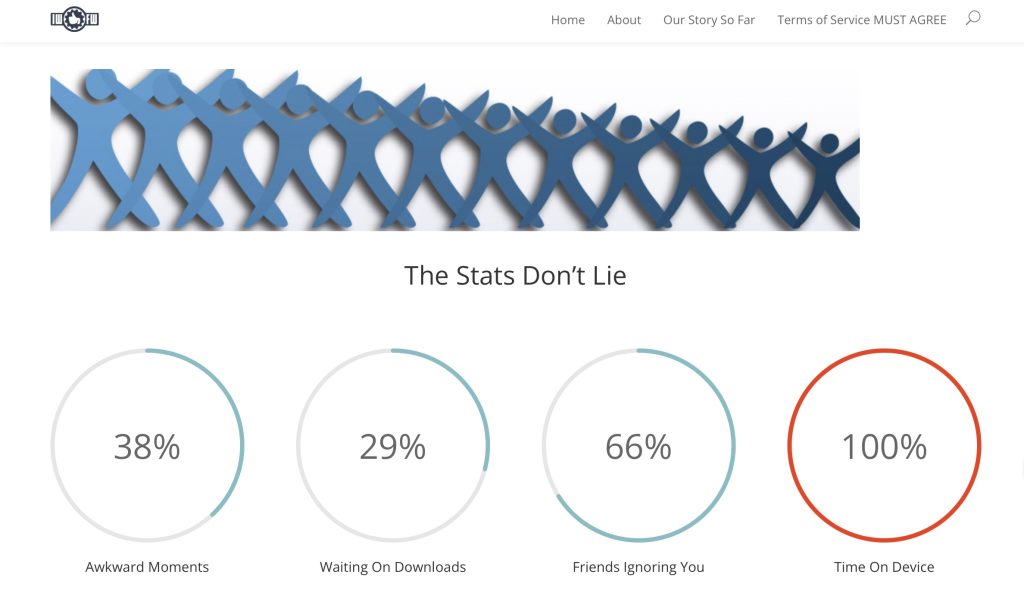

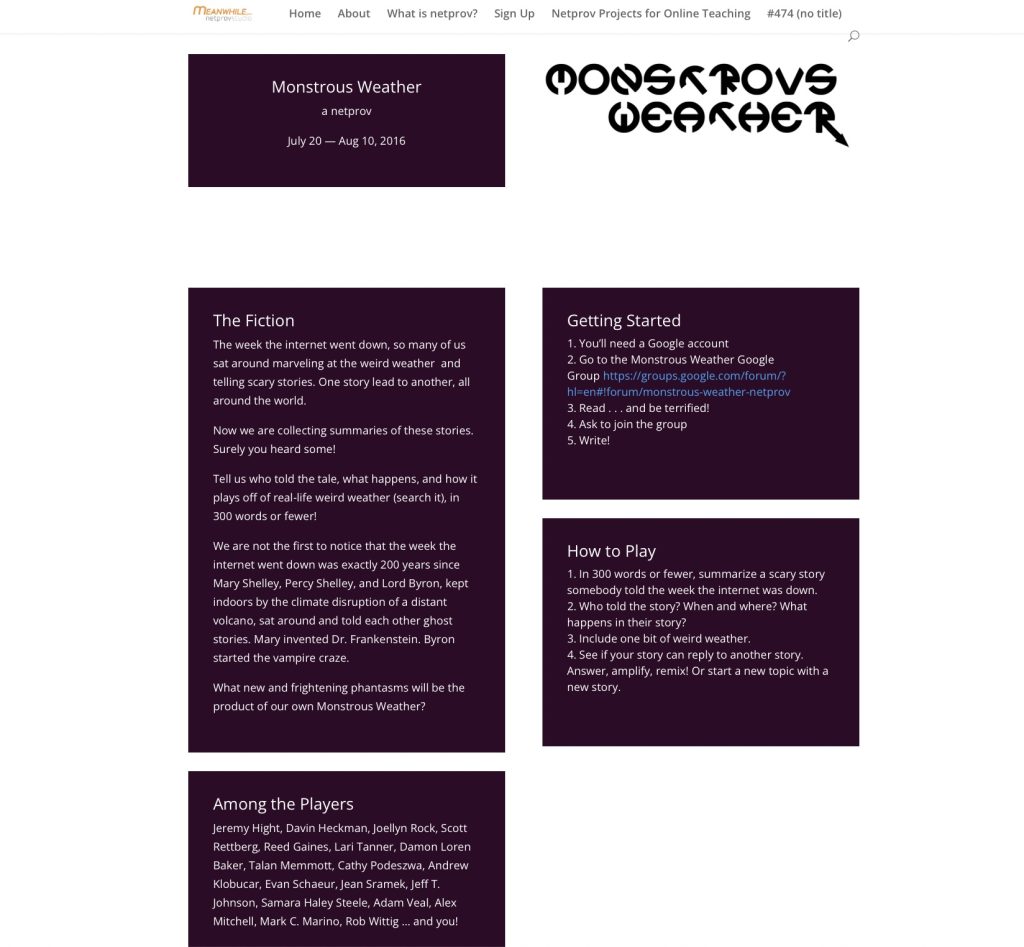

I’m just enjoying hearing all these stories. Well, I feel like similarly, I was doing netprov before I knew I was doing netprov. So, I ran this humor magazine, online experimental humor magazine in the late 90s called Bunk Magazine (http://bunkmagazine.com). And we were always trying to do these projects where we would sort of have had a similar netprov vibe that we were trying to recruit writers who maybe weren’t in the digital space into the digital space in projects that had clear guidelines and prompts and structures. One of them was called The Los Wikiless Timespedia and the idea was that the Los Angeles Times had tried to keep up with the Digital Times (and there’s not a publication called the Digital Times, but our digital moments) by turning its whole op-ed section into a wiki. And you can imagine how that would turn out. It pretty much went the way you expect it. So we decided that since they were doing all this bloodletting of cutting all their journalists, that maybe they would go all wiki and see what would happen. And again, it had disastrous and comical results. And then there was lots of micro reporting about people’s children’s soccer games and people reporting about the graffiti in their neighborhood, but then that would lead to other things. And one of the people who wrote on that was Scott Rettberg, who wrote as Lars. And I think that brought me onto his radar for whatever reason. We collaborated that way. And then in 2009, I tweeted that I thought my life would be better if I had a work-study student who ran my social media. And my next tweet was that I have this work-study student who runs my social media, and his name was Workstudy Seth. And you can read his adventures online. And I did that for about three weeks. It led to some people enjoying and other people eye rolling and Matt Kirschenbaum asking me in an airport, wait, just to clarify: was there an actual Seth? But then one of the people who saw it was Rob. And so in 2011, we were in Norway because he was doing his Masters at Bergen - again, with Scott. I guess that’s kind of how that story ties in. And he said, Mark, I just want to talk to you about Work Study Seth, because I thought that was great. I said, I’m glad because everyone else thought I was just goofing off and trying to avoid grading. And then he said, yeah, we should do more of that. I said, what do you mean? He said, we’ll just call it netprov, and we’ll just do it all the time. I said, okay [laughing], that sounds good. I don’t know what that would mean. And of course, then he did Chicago Soul Exchange. Then he did Grace, Wit & Charm. And then I guess maybe the first one we did together was the tweeted version of the Los Angeles Flood Project, which ran for about a weekend. It was a little bit War-of-the-Worldsy Twitter experience of what would it be like if Los Angeles was hit by an epic flood. That was my first time, I guess, seeing with a large group of people what real time improvisational, collaborative writing would look like under a framework. I guess I should also mention that with Grace, Wit & Charm, I was a writer for one of the characters and sometimes more of the characters, depending on how things were going. So it was fun to see how Rob was sort of inventing what it would look like from the inside, how he was scripting these story arcs for people, there were Tweets that were drafted ahead… My mind was blowing. Tweets drafted ahead of time. And then to see how that mixed in with the live shows with Cathy and the other players, those were really extraordinary.

Anna Nacher

Thank you so much. It ties in nicely with my idea to have some kind of oral history of electronic literature because we have lots of books on electronic literature, right? But being in the middle of it, participating in many panels, conferences, conversations, I have an impression that we need this other side of history. Like who met whom, at what point and what they did together—that kind of story. So, thank you very much for sharing. And Rob, is there anything that you haven’t written in your book yet in this regard? What was your way into netprov?

Rob Wittig

Yes, I think my path is laid out in my netprov book. I appreciate hearing these other paths, and I really appreciate these collaborators that we’re talking with today. Collaboration is very important and precious to me. A really early bond with Mark was when he came to me and said, “Oh wow, this reality TV star with a million followers on Twitter has offered me his Twitter account while he’s playing Celebrity Big Brother in England. I’ve started tweeting as him in a way that’s guaranteed to make people realize it’s not him. And so all his fans know that there’s an imposter. But now what do we do? What should I do?” It’s the pleasure, excitement, and sometimes fear of these intense phone calls… Of, like, what do we do now? People are freaking out. And the behind the scenes fun. It’s what Joellyn was talking about in terms of the wonderful, edgy looseness of creating on the fly like that. And that convinced me it was an art form.

Anna Nacher

Thank you so much, because my next question is about your creative practices, because you’re all, to various degrees, creatives. How has netprov influenced your own creative paths? Is there any kind of influence, do you see any kind of relations between your participation in netprov and how your creative paths have been developing?

Joellyn Rock

There’s almost always a narrative component in my creative work. I’m mostly a visual artist, but I cross over into storytelling, and I often work with old stories. But netprov influences me by realizing the stories don’t always have to be old. Well, they can be 15 minutes old to be old. So sometimes I think netprov plays with very recent history in a way. It plays off of popular culture, movements and trends. So that’s interesting. I think a big way that it’s influenced my delivery of digital media artwork is realizing that these platforms like Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, all of these social media platforms are vehicles for art to be distributed through or even gleaned from. You know, I think in a way, netprov does a cycle of gleaning out of social media and then pushing story back out into it. And so I think it’s made me rethink and be open to and consider other ways to pull in those sources of text and imagery. And so when I did FISHNETSTOCKINGS or we did The Sophronia Project, different projects where we have pulled text off of Twitter or pulled off of Google Forms. Mark and Rob are particularly genius about going, you know, what happens if we write a thing in a Google form. Just taking the very mundane tools of the workaday world and subverting them. So that’s super influential in the way I think now about creating new projects. It’s like, “oh, and I could” or “what would happen if”—so that’s how netprov’s changed my work.

Cathy Podeszwa

So my real work is… I’m a scientist. I’m a biologist, and I teach at a tribal and community college. So I’m a little bit split. It’s such a good question, so interesting. I think initially it allowed me to really enjoy some of the social media that can be unenjoyable. Like Twitter, we did All-Time High on Twitter, which was so interesting because we were just all connecting at a particular point in time, and then we would interact with each other and you didn’t really even know who you were interacting with in a lot of cases. I was always interacting with Mark, apparently, but I didn’t know it [laughing]. We had, like, three characters that were going on and working together, but that made it—like Joellyn said—obvious to me that these platforms could be used for actual fun and for creative work. But then it all got smashed in 2016 when somebody started using those platforms for lies. And it also became clear that some of the stuff that we had done, when you’re just completely free on social media and just kind of throwing messages out there, it started to become dangerous. It started to look dangerous. Some of the stuff, we were just lying, I mean, we were just pretending that we were burning a school down. But looking at that from the outside world, you wouldn’t know what was happening, and you might actually think that that was real. So it actually changed my idea of how you could use those platforms and made it seem like they were almost not usable—which is too bad, because I felt like I could see how they could be really fun, and then I could see how they could be really dangerous. So the danger just kind of took over and wiped out the fun.

Anna Nacher

Thank you, Cathy. This is the topic I’m going to get back to in a while. This really unstable borderline between fiction and facts nowadays and how it has changed over the last couple of years. So thank you for bringing it up. Rob, what would be your answer to a question how netprov influenced your creative process? Or, is netprov your creative process?

Rob Wittig

In the big picture, I would say that up until the point in my creative life that I, in some sense, fully committed to netprov, I still was open to being tortured by a childhood vision, a teenage vision of what the literary life was and what literary success was. It was like Kurt Vonnegut’s career. Like, that’s the career and why am I not having that career? Even though that career wasn’t even still possible in my era. Or: why am I not a successful screenwriter? Something like that. Then there was this wonderful moment of relaxation and release: I just knew down to my bones that this is a real art form. And I have read enough literary biography and literary history to know that the beginnings of art forms are always really shaky and people don’t believe in the new forms at first. I know how many of the canonical works we love were the secret side project or the pleasurable escape, the fun project off to the side. Voltaire thought his literary legacy was going to be these really stupefying plays that they still can’t really be produced in France because they’re just so formal and neoclassical. But his fun projects like Candide were the ones that people of our time most remember. So it allowed me to just commit to the fun of it and not worry, to just take off the heavy backpack of expectations that had been weighing me down. Since then, things have been a lot more fun! And then I would say, just technically, it allowed me a kind of escape. It allowed me to not have to write sentences like “the gravel crunched in the driveway as Maureen drove the car back from campus“ or “Fred sighed heavily as he opened the door to the musty summer house“. It’s like, you don’t have to do any of that stuff, you can just do fun, living language that’s more like conversation. It feels more alive, more contemporary, more accurate. It’s how people think with language mostly, rather than when they do formal “writing.” People go through contortions to translate a living experience into an older, archaic literary form. It’s like: why do that? You talk great, write the way you talk and go for it! So it helped me do that.

Anna Nacher

Thank you so much. I just thought that maybe netprov is a perfect form for academia. Considering how many people feel imposter syndrome, we would just go pretending we’re all academics, right? We could do that on an everyday basis.

Mark Marino

I’ve been brought into electronic literature through the narrow kind of arcane keyhole of modernism and literary modernism, and that meant that I was brought up to make things that would be readable only by a very small group of people who are highly trained to read things. But I also had been brought up reading Mad Magazine, a magazine that was satirical, that asked you to fold up its back page so that you could find a new picture that was the punchline of a joke. So suddenly magazines were different and there were comics in the margins and things like that. So I think I wanted to see this combination of not high and low, but satirical and the literary. And Rob really had his finger right there, at that point on the map. And I think I like this idea of doing fiction in public, like art making in public. It’s like guerilla theater, and when it works best, gets the consent of everybody. But, you know, sometimes it infiltrates in different ways. And again, that sounds like a topic for a later moment. It also helped me to work on time-based storytelling. Because especially when you look at projects like Tempspence or The Speidi Show or Occupy MLA or even All-Time High or I Work for the Web - when those posts happen, there’s storytelling in the gap, right? It’s not just significant what happens in that moment. Then maybe a day is going to go by and then another moment is going to happen. And then for me as a storyteller, imagining what happens in that time in-between was really interesting, and it wasn’t like anything I’d ever experienced in the digital realm. So getting to write serialized content or time-based content really has led me further and further into thinking about games, improv games and other kinds of writing games to play with people that are somewhat a leap in, but then sometimes much more accessible. You know, like a traditional board game might be, like Outburst or Cards Against Humanity or something like that. Think of these as games that people can play with other people that you love. And again, that’s the thing that Rob has really shown me. This is definition where it’s the voluntary healing of necessary relationships as one of the definitions for netprov. I find it to be very powerful and very true. A lot of my relationships with even this crew here have come out of netprovs. And I guess the last two things are that it may give me an art practice that’s both more improvisational and also more emergent and then collaboratively emergent, right? So you write something, a headline of something in a Tweet or on a Reddit board or something like that, and then Cathy jumps in on that, and Joellyn makes some images from that, and Rob jumps in on that. For some of the early netprovs, we really scripted things out ahead of time and then we learned to let it go. I love Davin Heckman’s definition of this as being a riderly text.1 Not a writerly or a readerly text, but riderly, like you’re surfing waves. That’s the true cyber text at that point, right? Because it’s responsive to what this collective is creating in the moment. And of course, in the spirit of improv and ending everything as best as you can. Anyway, it’s really opened up a lot of artistic practices for me, I think.

Anna Nacher

Yeah. Thank you, Mark, so much for sharing this. I’m not sure if you’ve heard about this spontaneous, political fiction performance that has just happened last week. I shared it on Twitter, the story of how Kaliningrad has been renamed Kralovec2, which emerged as a Central European reaction to pseudoreferendum in Ukrainian territories invaded and occupied now by Russia? It was massive. So many people got involved with it, including some institutions like Czech railways and Prague metro. It was amazing.

Mark Marino

That’s so wonderful. To me, that’s netprov in its purest form, in the most productive communal form, as opposed to maybe some of these other ones we were talking about.

Anna Nacher

It is massive because at this point it consists, I think, of hundreds of tweets. I’m trying to map this whole universe. Which actually brings me to my next question, that has appeared when I started reading your book, Rob, and also based on the experience I’ve had with my own students, who at some point participated in Moody Locales in 2020. Is netprov for already established communities or could it be used as a community-building tool? What is your experience with that?

Rob Wittig

I think it could be used as both. I think to build new communities takes more organizing time. And that’s something that has not been in abundance in most of the netprovs that we’ve done, except for the summer ones, since we’re teaching during the school year. It’s what I’m am pointing towards at the end of the netprov book. I have this dream—I don’t know quite how to do it—of taking an urban community in America and a rural community in America, sort of stereotypically on very different sides of the political spectrum, and building a game that would allow them to share about their experiences in a way that just tries to keep them out of the political habits of speech and see if you can build understanding. Because the more you know about people’s everyday lives and background, then things go better. I think there’s a possibility, but it would take… I really would have to have an organizer in each community who really knows that community and have them work together. It would take a lot of process, but that’s something that I would like to try.

Anna Nacher

Yeah. Thank you. Joellyn has just sent this brilliant remark in our chat that trust is an issue. So I’m expanding my question a bit: can netprov be a means of reclaiming trust between people or overcoming the divisions? A deeply divided society is not only an American phenomenon, it happens pretty much all over the world.

Joellyn Rock

Yeah, I think it’s very possible. But I do think there’s one thing that’s been a pleasure about our, let’s just say, pre-Trump netprovs versus post-Trump netprovs. Our pre-Trump netprovs could play with fake accents in our own identities and kind of slip into those social media networks and grow. But as Cathy pointed out, that changed as people began to worry what was at stake with lying on social media, with fabulations on social media. But I think if you’ve had it set up more like a multiplayer game where the rules were outfront and people from around the world knew they were playing a make-believe game together, then with the safety of those constraints… I mean, we know there’s lots of terrible stuff that happens in the gaming world, with sexism and stuff. So there’s always a need to monitor and all that. But I think it could be a cool way for people to build community, especially if you were trying to do world building together. Right? And I think netprov could do some really interesting things. I want to cycle back to Davin Heckman’s thing about netprov being riderly. So my literal favorite moment of playing in a netprov is when Davin and I were both writing on I Work for the Web… I didn’t know him very well. And Mark, I don’t know if you or Cathy were on? It was pretty late at night. Rob had actually gone to bed, he wasn’t playing the neprov anymore. But it was the moment where the unions were organizing and there was a big kerfuffle at Nighthawks, which was the imaginary… What was it? The meeting place?

Rob Wittig

Nighthawks is the bar where all the web workers in the world go after work.

Joellyn Rock

Yeah. So there was something really sort of mind blowing and exciting about creating it, and maybe it’s partly that I’m a visual person, but that it was very place based, but it was an imaginary place where things were happening and we were playing off of each other, and there were other people on the netprov I Work for the Web at that same time, but I didn’t know who they were. It might have been Talan [Memmott] and Davin [Heckman], and later I figured out it was Davin. But I couldn’t go to bed because it was so fun to see what everybody was imagining was happening in this space. It would be like if you imagined a big protest march with all those different dramatic things that could happen at a protest march, right? And I was like, oh my God, this is what you can do with netprov. You can really play out some fantasies about society in a way, but also through your little characters you’ve invented. And I found it just super fun. The other thing I want to connect with that is like listening to children play outside our window. We have this very active group of young kids in our neighborhood that fantasy play. When I hear them, I hear that magical thing that happens in childhood where you’re all working together to create a virtual something and they’re working it out and they’re tussling a little bit about what the reality is. But it’s in that tussle that the reality gets defined. And that it can happen inside netprovs is really exciting and could be interesting for social change.

Anna Nacher

Thank you. Thank you so much. Yeah, we have this ongoing discussion on how electronic literature can actually contribute to social change, the required social change. So I think netprov definitely can be a part of that. But yeah. Mark, what would you say about the netprov as a tool of community building, overcoming divisions or instigating social change?

Mark Marino

Yeah, I apologize but I am going to jump us ahead to the next question. To me, all of netprovs are community building, whether it’s One Star Reviews or whether it’s Destination Wedding or I Work for the Web or just even within our own community. When I look at, again, Cathy and my relationship through the various characters we played on All-Time High and of course, Rob and my continued development of our relationship. But it’s hard for me to answer that question without also touching upon some of the other issues of what bad actors bring to the table. And I guess maybe if I were to start on the latest version of this, I think what Rob and I love is that we live in an Internet moment where these sorts of emerging things that have this netprovey character to them. People are in this mode where a meme will come across and then they’ll play it as a TikTok dance and they’ll do it and they do variations on it. And so I think part of netprov is trying to help promote that spirit. Again, I don’t want to take us too far off the question, but when we talk about bad actors, like Trump or even some people have said is QAnon some sort of netprov? And I think it’s important to differentiate between good and bad actors. I mean, literally, like a demagogue, right? Think about Hitler. That’s a cheery subject. And then think about Charlie Chaplin playing Hitler. Right? Like, they’re both using theater essentially to do the things that they’re trying to do, but we don’t say that Hitler so soiled performance, that we’re not going to perform anymore, right? Similarly, all of our digital technology, as far as I could tell, comes from the military, but we don’t stop using our computers because they were also used to generate nuclear bombs. So I just want to be careful with that. Also, the other thing on the other end of this is the verification industry that wants all communication online to be authentic. Okay? And they want to verify your identity, make sure you are who you say you are. And why do people want to do this? So that they can sell your data and harvest it. I’d hate to see us lose the playful spirit with digital representations because it opens up the fact that every utterance is a kind of performance. And you can use those for good or for bad. I think that a lot of netprov just reminds people: oh, by the way, instead of shooting that modified picture of your body and posting it to Instagram in this pursuit of likes that you probably will never fulfill the hole in yourself, maybe you can tell a story or maybe you could start playing in a collective poetry game? I mean, Spencer Pratt was Spencer Pratt himself. His practice was pretty Trumpy and in some ways, right? In some ways, it’s an abuse of performance on social media, exploiting himself. At other times, it’s super creative and involves hummingbirds and making espressos and loving Taylor Swift. On a radio broadcast about War of the Worlds, produced by John Barber, H.G. Wells and Orson Welles have a rare chat. https://www.vancouver.wsu.edu/news/re-imagined-radio-explores-stories-may-have-shaped-war-worlds H.G. suggests thay America (in 1940) could still play at war because they were not yet in a war. I wonder if this comment speaks to Cathy’s concerna about Trump and hia use of social media. Maybe she, rightfully so, felt we were in a war and so could not afford to play. I respect that sentiment, and yet still want to play as an act of opposition, rebellion. http://www.reimaginedradio.net/episodes/wow/index.html#2022So I guess it’s more like a garden, you’ve got to pull the weeds, and following Candide, tend your garden, put fertilizer and water it in the hopes that some good stuff will grow.

Anna Nacher

Thank you, Mark. Cathy, would you like to add something to what Mark has said?

Cathy Podeszwa

I appreciate everything Mark says. Always.

Anna Nacher

We agree.

Cathy Podeszwa

That’s really important, I think. Really, really important to think about it in that way. I was going to say I actually belong to what you could call a netprov community. It’s like you said, Mark, a lot of people are doing community building with all these online tools. So I’m part of The Pit, which is The Bachelor-based group that the Game of Roses podcast created. They got so involved in understanding and getting all the minutiae for all of the history of The Bachelor franchise that it started driving them crazy. So they talked about it like being in The Pit, and then they started dragging other people into The Pit, people who were Bachelor fans but thought about it in a different way—or not necessarily fans, but more… like if you hate-watch it and things like that. But it grew over COVID in an interesting way. They have a Patreon, they do podcasts, they do live streams. So there’s a connection with the people who are in The Pit. They have merch. It’s two people, Lizzy and Chad. And Chad actually started coaching players to go into The Bachelor, and now he has had people in the game, and so he is influencing that media, which is wild. But that reminded me of our thing with the Speidi show and hooking in with the reality stars, Spencer and Heidi in an early phase, and creating something around that. But it’s interesting that’s just like there’s a lot of intense creativity and I’m definitely a Pit Dweller. I feel that’s a community. People show up wearing their merch on Instagram and there’s the Dark Seeker who found the old seasons that they couldn’t find, and so now she’s employed by them and posts on Instagram. And so it’s a really fun community. Interestingly, I think they reduce the bad actor quality of it because it’s a Patreon, so you pay to be part of it. So that’s one of the ways you can reduce bad actors. But I just wanted to mention that because I’m a Pit Dweller and I’m always dragging people into The Pit. I think this intensely creative thing is very much on our wavelength.

Anna Nacher

It again ties in nicely with another topic. I would like to also bring up the issue of platforms, because we all struggle with what platforms became in our life, how platforms have changed the last couple of years. And I really like your metaphor, Mark, about tending to a garden. Maybe it’s because I happen to have written about gardening e-literature at some point, and I’m still inspired by such metaphors. So I’m wondering, do you think netprov can be a way to interrogate platforms or to actually put fertilizers into them? Not in terms of helping them develop technically or helping them to develop data mining practices, but rather as being more attentive to the actual use of platforms. That’s something I think increasingly comes to mind when I think about netprov. So that would be one question. And another is whether you found out what platform was actually the best for carrying out netprovs, in terms of being the most flexible or the best accommodating the need to be creative.

Rob Wittig

Well, yeah, I said early on that we’re kind of cuckoo birds. We lay our eggs in other people’s nests. And that was to differentiate us from the many people in electronic literature who write platforms and write programs and do the programming. That’s not my skill set. The other thing that we say that I like is that we use available media and that’s kind of a neutral way of putting it. As to which one is the best… it’s really time dependent, like pre 2016: Twitter, fine; post 2016: handle with care. Not that it’s impossible, but it’s a certain kind of project. And each platform has its strengths and weaknesses in terms of organizing things. But in most of the netprovs that we do the fictional characters participate in pretty much the same way real life people are participating in that medium already. So the basic use pattern of the platform is based on real life. And what we’re changing is the content and we’re doing a more imaginative thing. It has occurred to me I would love to have the time and a bit of financing to think about a proprietary app. I’ve got a whole potential vision: you have this app, it’s inexpensive, it’s you and your friends, plus the featured players, and then you get a new game, a new concept, a new playing field every month, first of the month. You play for a month and have fun. Something like that. But again, that’s just a starting point. Hopefully, I’ll have some time to investigate that because – just as we were saying earlier about Patreon paying for it – it could help make it a safer environment. Although, again, I like that everybody uses what they’ve got, and they respond in the moment. The #Kralovec thing is incredible, that’s a perfect example. And it partly works even in this really tense, dangerous time. It works because the fundamental premise is so absurd that everybody kind of gets it, that it’s an impossibility. And so it’s clearly a work of the imagination. So I think in times like these, my thought is, I’m not as comfortable with work that is closer to the line of “is this real or not?“ I’m liking work that’s clearly absurd. Or we say, this is a game. Like Joellyn was saying, let’s just call it a game. And we just love when new platforms come out and the featured players share their glitches with each other and go, “here’s an interesting glitch that could be fun,“ or “here’s a weird little interesting pocket of ill-planned programming that could turn into something fun.“

Anna Nacher

Yes. Thank you. By the way, the #Kralovec story was taken seriously by the Russian state media who threatened all of us over this prank.

Rob Wittig

Have they understood now that it’s a joke?

Anna Nacher

I’m not sure whether they don’t understand or, rather, they aren’t willing to understand.

Rob Wittig

Got you. Wow.

Mark Marino

Maybe I’ll jump in just for a little bit. I think a lot of electronic literature is about its form, and I share an impulse with, I think, a lot of people here just thinking about how every surface can be a creative writing surface. So whether that’s a whiteboard in a classroom, like when Rob leaves his fictional classroom notes up, or if it’s someone writing “Wash me” on somebody’s dirty car… Again, we should have no delusions, especially when we’re using these free-to-use platforms, that we’re just making money and giving data to other people, other larger groups, typically. But to me, those places can be so toxic for people. And if we can bring a playfulness or creativity to them, or if we can help people see how they can be part of their creative outlets, then that’s the win. Slightly different than Rob, I guess there is a guerrilla theater impulse in me, maybe, that in its best mode is sort of surrealist détournement or something like that. But I think like poetry in motion or sticker novels or getting fiction making and conscious performance into the real world seeded into everyday lives to me, even post-Trump, is still a really interesting project. That again, I love hearing about the #Kralovec project. That sounds like the purest form of it. To go one more step. For us, almost every netprov exists on a different platform. And we’re always try to push back on platform a little bit, whether it’s Google Docs or Reddit. I don’t know if there is a best platform just yet. They bring out different things in the netprov. If they’re more time based, like Twitter or Instagram, then that brings out certain characteristics. If they’re more image based, it brings out different characteristics. If they’re a discussion board… We have done a lot lately on discussion boards just because they feel like they’re a little more stable. But again, it just brings out a different kind of play… It might make it more asynchronous than synchronous. But yeah, I think every digital surface could be a creative play space. And it’s fun to test that theory, I guess.

Anna Nacher

And all the platforms have their own constraints, I believe, including its corporate nature. Probably the corporate structure, the things we don’t know about are one of the strongest constraints because we don’t really know how Twitter or Facebook really operate, right?

Joellyn Rock

I just like Mark’s idea that if it’s in public space, I was thinking that it’s like street theater. Do you want to give up ever doing street theater by closing everything off into an app? I think it would be cool to have a proprietary something for netprov because, I guess, it’s like games that get played in a lot of different ways. Some people play chess out in a public park, where people can walk by and watch them play chess. Other people play chess with themselves or against the computer—there’s all these different modes. So I like the idea of netprovs that could be played on multiple platforms. A lot of the netprovs have been time-based in that they get launched by Rob and Mark. There’s a launching and maybe a preview playing by the featured netprov players, the sort of small group to test it. And then they launch them into educational environments, with their students and with students at other universities. So each of those situations requires an awareness of… If we ask everybody to use this platform, is it too expensive for the students because they have to pay something to be on it? Or is this one that they’re all already using? TikTok or whatever it is? Is that a good one? I don’t know. Did you guys ever do a Snapchat one?

Mark Marino

I think TikTok may be next. Let’s just say that.

Cathy Podeszwa

It’s interesting. When we did Grace, Wit & Charm, and Rob was trying to describe what it was—I really actually had this vision in my head of a Brady Bunch screen, where all of the different people are coming in for a meeting, like a Zoom meeting.3 It was before Zoom. With just multiple screens, and there’s each person on a screen, and that you would have people who were doing things. It was kind of a vision of connective theater, where there would be people in different places in the world and they all come together to do this project, but in a theater and being a performance. Each person would have their own role, and then they would be coming together in a type of a Zoom thing. I have these memories of thinking about it that way, when we were thinking about doing Grace, Wit & Charm, because I didn’t really understand what it was going to be. So in my head, I apparently created Zoom, from a Brady Bunch model [laughing]. And now I’m just like… Wait… Because I really actually like Zoom as a platform—you know, you’re in Greece, I’m in Duluth, and Mark, I think he’s in LA. Who knows where Mark is [laughing] - but having some kind of get together like that. Each person bringing something to perform that maybe the other people don’t know about. So Zoom has always been in my head, even before I knew it existed, or maybe even before it existed as something that could be utilized. I like thinking about that and I like the visuals of it too. I thought Twitter was so flexible, and I loved just being in my head and having all of these… Like Joellyn was talking about having these worlds being built in your head—you’re building them together and just through words, not through any images or anything. And that, I thought, led to some really beautiful things, kind of deep connections, and fun. Like, when we were kids, we played outside. We always had all these different imaginary worlds going, and it really was a good way to do imaginary worlds.

Anna Nacher

Yeah. Thank you so much for this. And I’m so grateful to you for inventing Zoom. It saved our lives in the pandemics.

Cathy Podeszwa

Bob and I didn’t just give it away.

Anna Nacher

So it seems a next stage in netprov development would probably be an app. Which is something I might like, although I’m also of divided mind right now because I really love Mark’s idea of throwing some playfulness into platforms, a sense of guerrilla tactics and tactical media. If there is no playfulness there, it’s going to be just industrial agriculture of efficiency rather than a wild garden. And actually, I think, that’s how we are prompted to interrogate the operation of platforms. Which tempts me to ask about a sense of netprov historicity. Do you think it has changed since the time of its emergence? Because in our conversation I keep hearing these terms: pre-Trump, post-Trump. I think there may also be some changes related to the history of e-lit or its recent creative tools, such as memes. I think pre-meme netprovs may have been different, but that’s just my guess. I’m really curious, what do you think about how netprovs have changed in the course of its existence as a genre so far? I

Mark Marino

I hope Rob would have an answer to this one. Yeah, I think it has certainly evolved with the media ecology. So there’s this moment where there are these early adopters, I think about things like Twitter, a lot of academics are jumping on it and other sort of technophiles. And then there’s the point at which it becomes super mainstream and it warps and turns into something else. Similar with Facebook, there’s time when Facebook was primarily just college students, just young people, and then it eventually turned into everybody’s great aunt and great uncle sharing stories, much like they would newspaper clippings back in the day. And again, nothing gets worse, necessarily. But things become… They become less novel, sometimes the communities of practice change. I guess, it’s a media ecology, it’s an ocean. In terms of forms, our practices change with the forms, change with the moment. I think Rob might be able to speak to this certainly better. In some ways every netprov is responding to a different media and cultural moment. By its nature, those practices shift. But I do want to say one thing - it does feel like we can point to more things that are like netprovs now than we could when we started. Like #Kralovec. Or again, I think about the Brooklyn Zoo snake that escapes that Rob writes about in his book. We just have more of those that we can point to. So when you invite someone to play, sometimes it’s easier to give them a context. You mentioned COVID… COVID gave birth to so many… Zoom theater was a thing that happened all of a sudden to everybody. Suddenly everybody knew how to use video. I remember when you had to explain to people how to use videoconferencing software, back before Cathy invented it. [Cathy giggling] Those were tough times. You only had Skype - unless you had international family or friends or colleagues, it was very unlikely that you had ever used this before. And now, again, iPhones have turned every call into a video call, it seems. And then video conferencing is just de rigueur. And then just one more thing I want to point - out there are things like that netprov that was on Facebook - we didn’t create it - where we’re all pretending to be ants in a giant ant colony.4 And again, I think over time, this playfulness that netprov names but does not ever claim to invent has started to spread organically and naturally amongst people’s online digital practices in ways that are really exciting. And again, our netprovs are just a part of a larger wave that seems like it’s growing.

Joellyn Rock

I was thinking about how when we first did early netprovs, and it may be partly that Duluth is behind the rest of the world a bit, but a fair number of people had never used Twitter. So there was this learning curve of wrapping your head around this improvisational writing game, but also figuring out how to use the tools. And I think what Mark pointed out was that overnight the pandemic trained everybody onto some tools all at once and made it clear that people can all adapt to something like Zoom. In a week, we all just jumped on and learned how to do it. So to me that’s exciting for the future of netprov, because it just shows that you don’t have to worry about that resistance to the tool. Because basically what you’re saying is we’re going to play a game and it uses this long bat and this ball. And you’ve never used a bat and a ball before, so how do you do it? But it shows you that people can learn how to hold up the bat and hit the ball with it and actually really enjoy that. And so I think there’s something in that—in terms of platforms and their evolution—to not be afraid. I think we’re going to get some new tools soon, aren’t we? I think that’s partly why Grace, Wit & Charm is an interesting one to get back into because of the use of avatars and virtual reality and stuff like that. It’s probably going to become less scary and oh-I’ve-never-done-that-before, so I’m certainly not going to play your game that uses that tool. I think the pandemic proved to us that people can jump in and learn things faster than we think.

Anna Nacher

Yeah. Thank you, Joellyn. I need to intervene. Duluth is not behind everything. Duluth is ahead of everything. Cathy has invented Zoom, and no one seems to be on Twitter these days, so you’re so much ahead. The rest of the world is trying to catch up with you.

Cathy Podeszwa

Yeah, there have been so many tools that have been produced in the last ten years. I guess like ten years is the Grace, Wit & Charm anniversary, right? And it’s mind blowing. Honestly, just how much stuff has been flying across and how often it changes. I guess, some people actually do use Snapchat as sort of a nostalgic kind of use. But I don’t want to use TikTok, I don’t want to get into it. It just seems like crack or something. It just seems almost dangerous. Things have just changed so much. But I think Joellyn is right that people maybe are just used to learning new platforms a lot more quickly now and can do it. And we’re more digital humans, I guess, than we used to be. I did walk through my own life thinking about the immense amount of technology that I’ve learned over this time, it blows my mind. I actually kind of am more interested in detechnologifying myself in a lot of respects, but that is the kind of biologist in me. I’m grabbing onto the biological world.

Rob Wittig

I agree with what everybody is saying, and it is sort of I do remember the really long breath that you had to draw ten years ago before you explained a netprov to someone. “We’re doing this project called Grace, Wit & Charm.” “What’s it about?” Deep breath. “Well, are you familiar with Twitter? With motion capture suits? Can you imagine a workplace comedy set in a virtual reality studio?” It’s amazing how difficult it was to explain that concept at that time and how much easier it is now. We did a sort of a quick revival, and now we’re actually playing with the possibility of an ongoing version of Grace, Wit & Charm on Twitch, and it’s much easier to explain all that to people. If you take 20 of my friends around the world and you propose any netprov to them, probably twelve of them are ready to play technologically. And then the other eight are like “what? I don’t know how to do that, I’ve never heard of that“. You just can’t tell. That effect is diminishing slightly, but it still is there. The historical thing I’m most focused on is something that hasn’t changed. There are so many people who, in their text messages to their friends or with their little groups, are super smart and they do creative, language-arts things that, with your literary critical hat on, are beautiful writing!. They have every characteristic of resonant, powerful literary writing. And they write like that every day, many times a day, interwoven with their other activities. But, sadly, It is completely compartmentalized! They never make that connection between their amazing creativity and canonical literature. I don’t know if Mark’s had this experience, but just finally, in the last couple of years I was able to teach creative writing and this thing happened that just took me by surprise every time. A semester of playing with Oulipo, and lots of netprov and creativity in new platforms and people saying, “I’m getting over my writer’s block and I’m having the most fun I’ve ever had writing!” The final assignment is: write whatever you want. And what came in was largely: super conventional genre short stories, super conventional poetry [laughing], super… There was zero carry-over from all of this joy of experimentation and writing! It’s compartmentalized into a structure where literature is this sort of ancient thing that is necessarily stilted and difficult and unpleasant, and all this other exhilarating creativity that I do doesn’t count. And that’s something… I’m really waiting for that to change! And as far as I’ve seen, it has not changed yet.

Mark Marino

And I just want to jump in there. Speaking of TikTok, which Cathy is going to be on, obviously, inevitably… I did post a link to her paper she wrote in 1991 where she called, just for the audio record, Planktons Tick, Paramecia Talk, where she does explain how that platform will work. I’ve been on TikTok for a little while lately. I’m not using it to dance, but I’ve been following a lot of people who teach you how to self publish. What’s interesting is they’re teaching you how to self publish novels and sometimes trying to get over this anxiety of what self publishing is all about. But what I feel like is happening is people don’t realize that they’re creating totally new things on Tik Tok! There’s a phenomenon that’s happening! They’re creating these stories. And when someone records a short 15 second video of themselves that can be duetted in conversation with somebody else, and then somebody builds on that when sea shanty show up again, and people do these amazing choral works where they’re layering one upon the other… Just the sheer level of creativity… Maybe in the pursuit of Likes or whatever, but, you know, perhaps our performance desires are the parents of certain kinds of invention. But more importantly, it’s fascinating to me that on the one hand there’s streams of people asking, “How do I get into this old print medium? Teach me how to become a published novelist.” And then what they’re not paying attention to is the fact that when they throw a filter on, they’re doing something that in some ways hasn’t been done in artisticin an artistic way in that moment. I love encouraging people to lean into that and just to let again put the novel back in the novel as Rob is always trying to help us do.

Anna Nacher

Thank you. Tik Tok is the whole new universe that my students helped me to discover. And it’s so addictive. At some point I was really spending up to 3 hours in one stretch just exploring it. I shouldn’t even mention that because that time was probably lost for my scholarly activities or anything else. It is so addictive.

Mark Marino

Lost? Aren’t you a theorist of new media? How can it be lost? [all laughing]

Anna Nacher

[laughing] That’s my excuse.

Rob Wittig

I’m going to make the argument that apologizing for a cultural activity is as close as you can get to a guarantee that it is a living art form. My whole career, I’ve just heard that “well, I do this thing for fun… I’m embarrassed, I shouldn’t be doing this, I should be writing my short stories, I should be writing a novel, I should be…“ I’ve told my design students, when they’re presenting, to listen—in each other and in themselves—for that apology, and pay attention, because that can be the sign of good new things. Why? Because new things are new even to you! And they look strange and odd even to you! And people are so wanting to have what they do be like the canonical thing. So they get the pat on the head and they get the good grade. But new stuff is just new beauty and you have to declare it new beauty based on nothing except maybe that you spent 3 hours on it and you can’ get it off your mind!

Anna Nacher

Rob, I love your definition. From now on, I’m going to stick to really exploring things. I have just one brief question. I mean, I have tons of questions that have not been asked, but I know that your time is limited. So anyway, just one brief question and preferably please answer with just one sentence. Who is the perfect netprover?

Mark Marino

Yeah, Rob gets my vote, too.

Rob Wittig

I guess I would convert that into the generic answer. It’s the person who apologizes, who loves it and apologizes. That’s the perfect netprover. Hopefully the apologies won’t feel necessary much longer.

Anna Nacher

Thank you. Cathy, what would be your take on perfect netprover? Who is or who are they?

Cathy Podeszwa

Nobody. Because nobody should be perfect. You should always be making mistakes and just strive to just do your thing and see where it lies.

Anna Nacher

Thank you. So encouraging. Mark, are you still there?

Mark Marino

Yeah. Have I disappeared? Oh, sorry. I like these votes for Davin, Jeremy and Rob5 [in the chat], but I would also vote for all the people gathered here. You know, I like Cathy’s answer a lot. I think it’s the person who picks up the digital medium either before they ask the question, how is this supposed to be used? Or when they’ve decided that that question is no longer valid.

Anna Nacher

Thank you so much. And Joellyn or vixen [a Zoom filter on], beautiful vixen on the screen, what would you say?

Joellyn Rock

I had said in the chat that… Can you see my mouth is actually moving [as a vixen]?

Anna Nacher

Yes, it is.

Joellyn Rock

I was going to say Davin, too, just because my experience of playing with him in a netprov was surprising and delightful. Because he doesn’t fashion himself as a creative writer. So when he writes creatively, it’s just kind of fluid and I don’t know him playing a game. Jeremy Hight was a prolific writer, but he was prolific in several different netprovs we did. You know who else was good? Mez [Breeze]. Mez contributed stuff to different netprovs that was really interesting and was able to go with it, like take on the premise, no premise is too weird, and take it three more steps weirder… Language-wise and imagery world building-wise. And even heart, with heart in it. One of the things that I think works and sometimes doesn’t get enough attention—even though Rob has it in the theory of what he wants to have netprov do—is that sort of connection to truth and the heart. I don’t know if I’m saying that correctly, Rob, but when people can kind of reveal some emotional depth within these absurd character scenarios and we see ourselves in it, or we can respond back in an emotional way in the narrative, that’s really the fruitfulness of what can happen, because we can all be clever on social media. Everybody can make a quip or whatever. What netprovs can do, that literature does, is it takes us into seeing the world through other people’s eyes and takes us into deeper water, right? Scarier places and catharsis and stuff like that. And a lot of us have experienced catharsis within a netprov cycle and that’s really fun and rewarding, and cool.

Mark Marino

That feels like kind of a mic drop moment, which means I’ll pick it up really quickly from the floor and just whisper. We didn’t mention like, Haley Steele, I think, a phenomenal netprover, and Talan [Memmott] and folks like this, but I would say for those of you watching this recording later or reading the write up later, the best netprover is you—meaning that each person can bring something that no one else could bring. So you just need to honor that. And every collective probably brings something that no collective before has ever brought and it’s fun to honor that as well.

Anna Nacher

I can only second that. I participated in a few netprovs to the extent that I was able at the time. Usually the problem is time zones (because I’m several time zones ahead or behind) or limited time resources in general. It is also my creative writing bloc, especially in English. But on the occasions that I took part in netprovs, it was something that instigated a very deep transformation in my life. At some point I just realized I can be as creative as I want, including my linguistic or grammatical flaws, and all irregularities. So I’m really grateful to you for netprov. Thank you so much for today’s conversation.

Works cited:

‘A group where we all pretend to be ants in an ant colony’ https://www.facebook.com/groups/1416375691836223 Heckman, Davin. “The Riderly Text: The Joy of Networked Improv Literature.” Hyperrhiz: New Media Cultures, no. 11, 2015. doi:10.20415/hyp/011.e04 http://hyperrhiz.io/hyperrhiz11/essays/riderly-text.html Wittig, Rob. Netprov. Networked Improvised Literature for the Classroom and Beyond. Amherst, MA: Amherst College Press, 2022.

Footnotes

-

Cf. Heckman, Davin. “The Riderly Text: The Joy of Networked Improv Literature.” Hyperrhiz: New Media Cultures, no. 11, 2015. doi:10.20415/hyp/011.e04 ] ↩

-

I write about it more extensively in the same issue of EBR - electronic book review. ↩

-

As reminded by Mark Marino in the Zoom chat window: in 1984 Cathy did a presentation with an Etch-a-Sketch where she showed the design of Zoom. ↩

-

Check it out: ‘A group where we all pretend to be ants in an ant colony’ https://www.facebook.com/groups/1416375691836223 ↩

-

Davin Heckman, Jeremy Hight, and Rob Wittig. ↩

Cite this essay

Nacher, Anna and Cathy Podeszwa, Rob Wittig, Joellyn Rock, Mark Marino. "Riderly waves of networked textual improvisation: an interview with Mark Marino, Catherine Podeszwa, Joellyn Rock, and Rob Wittig." Electronic Book Review, 6 November 2022, https://doi.org/10.7273/xc7z-t288