See the Strings: Watchmen and the Under-Language of Media

Engaged in his own kind of structured play, Stuart Moulthrop uses the concept of "under-language" to explore the boundaries, gutters, masked intentions, and hidden meanings of Moore and Gibbons' Watchmen, while simultaneously using the graphic novel to provide an equally complex, over-determined rendering of the term.

This essay was first published by The MIT Press in 2009 in the collection Third Person: Authoring and Exploring Vast Narratives, edited by Pat Harrigan and Noah Wardrip-Fruin.

High Magic

Comics belong to an interstitial form, occupying a privileged place between the dominant media of word and image. They are enough like long-form prose narrative for some to be known as graphic novels, and they are first cousins to storyboards, important genetic material for most films. Indeed, as Scott McCloud suggests, a comic is a bit like a film reel with a slow playback rate (8). Yet we should also mark a crucial difference between comics and film: the separation of visual units by a gap or gutter, so that arrangement and disposition strongly influence interpretation. Unlike film frames, comic panels are presented not singly but in groups, one page-or in book form, one bifold spread-at a time. Turning the page of a comic book presents a simultaneous array of images and words, which readers break down into the conventional, right-left-top-bottom reading sequence inculcated by print. This scheme is often discarded by readers and comics creators alike, but exceptions tend to reinforce the basic rule. Reading comics generally involves dual modes: scanning the page grid, and then focusing attention on a particular region within it (McCloud 95).

McCloud rightly insists that a comic is not a hybrid or synthesis of two modes but something more like a suspension, where combined elements remain distinct. To some extent, this duality reflects the history of media and culture. As Lev Manovich points out, the “logic of industrial production” that emerged in the last two centuries promoted a sequential way of thinking about the world, and to express that worldview, it encouraged convenient forms of narrative, from journalism and novels to movies and television shows:

This type of narrative turned out to be particularly incompatible with the spatial narrative that had played a prominent role in European visual culture for centuries. From Giotto’s fresco cycle at Capella degli Scrovegni in Padua to Courbet’s A Burial at Ornans, artists presented a multitude of separate events within a single space, whether the fictional space of a painting or the physical space that can be taken in by the viewer all at once … [S]patial narrative did not disappear completely in the 20th century, but rather, like animation, came to be delegated to a minor form of Western culture-comics. (322-323)

The historical nonconformity of comics may have more than academic interest. Keepers of the great traditions, as opposed to true critics like Manovich, have little time for “minor” practices. Meanwhile, those less attached to the cultural center find value at the margins. Take, for instance, Jimi Hendrix’s or Neil Young’s distortion-rich guitar styles from the late 1960s, or Grand Wizard Theodore’s invention of record scratching a decade later. The market masters have generally dismissed these techniques as gimmicks that define at best a limited niche-until those niches grow large enough to exploit. Meanwhile, a generation of grunge players and hip-hop artists hear possibilities for musical deconstruction, ways to fold back the conformations of media history. By flaunting outmoded, analog technologies like vacuum tubes and vinyl records, they expose and complicate the prevailing aesthetic of digital synthesis. Noise becomes interpretation.

“Minor forms” thus hold the seeds of major critique, especially when they play deliberately with ambiguity or doubleness. As Thomas Pynchon realized, there can be “high magic to low puns” (Crying 129). At any liminal point, or along an interface, value assignments tend to reverse: “everything bad is good for you,” as Steven Johnson polemically indicates (9). Watchmen offers an excellent case in point. By manipulating the interstices and invisible art of a medium that comes from the gutter, Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons have produced a work that reflects profoundly on space and sequence, and that, if read carefully, affords an important perspective on modern media.

Beyond Your Wildest Imagining

Watchmen was published in 1986-1987 as a twelve-issue series by DC Comics. Reissued as a trade paperback during the graphic-novel boom of the late 1980s, it has remained in print for twenty years, winning multiple awards and the praise of Marvel founder Stan Lee, who called it a milestone in the evolution of comics (Wikipedia). Moore, who conceived and scripted the project, originally thought about a multipart superhero story involving the Mighty Crusaders, characters developed in the 1950s and 1960s by MLJ-Archie Comics. He later adapted this concept to another defunct superhero line from the Charlton Comics house, which had been acquired by DC. Traces of these origins survive as grace notes in Watchmen: Nite Owl’s airship is called Archie, and Walter Kovacs (Rorschach) spends his childhood in the Charlton Home for orphans. These may be “fanboy” details, as Moore calls them, but they also indicate how deep the texturing of allusion runs in his work. In the end, Moore was not able to use the Charlton characters, probably because DC planned to feature them in new comics, while Moore envisioned a closed story arc where some major figures would die. The result was an original world with its own dramatis personae (Absolute P#).

Moore has said he wanted to create “a superhero Moby-Dick,” and indeed the work has been treated as a contemporary classic by both fans and scholars (Wikipedia). As its substantial entry in the Internet’s open encyclopedia attests, Watchmen blurs distinctions between popular and polite cultures, offering broadly accessible entertainment whose intricacy and technical sophistication invite careful study. Wikipedia cites four websites offering analysis of the work as well as a reconstruction of Tales of the Black Freighter, Watchmen’s comic within a comic.

These projects demonstrate a strong affinity between Watchmen and what Yochai Benkler calls the emerging “folk culture” of the Internet (15). Steven Johnson argues that technologies for easy access and repetition, such as DVD players and video on demand, have led television producers to more complex narrative forms, from the ensemble style of Hill Street Blues to the epic story arc of Babylon 5. Johnson sees a developing trend from “least objectionable” to “most repeatable” programming (160-162). Graphic novels certainly fit this pattern, especially those as rich and demanding as Watchmen. We might then propose yet another interstitial placement for this work, not between print and cinema, but between the old regimes of cinema and press and the electronic frontiers of the Net.

Watchmen offers an attractive framework or seedbed for Internet culture. Taking up this cue, in the early days of the World Wide Web, I deployed a reader’s guide or “digital companion” to the comic, noting that its narrative structure seemed well served by hyperlinked, multithreaded commentary (Watching the Detectives). Five years later, as contributions from readers of the site accumulated, colleagues of mine reengineered the original site as a protowiki, streamlining the process of textual expansion. As we will see, this convergence of Watchmen with what Michael Joyce calls “constructive hypertext” (10-12) is far more than a coincidence of structural features and literary tastes. By illuminating the boundary zone between dominant and nonconforming media, Watchmen offers a great deal to those concerned with emerging textual practices.⏴Marginnote gloss1⏴With regards to Bizarro World, it is worth noting that the absurd inversions in the Bizarro Superman comics of the 1950s and 60s typically anchored themselves to middle class American norms and institutions in order to achieve their comic purposes. Imperfection is always registered in relationship to an implicitly perfect ideal, thus Bizarro Superman has a wife, a dog, children. They live in a suburban neighborhood. Bizarro Lois cleans the house by making it dirty.

— Davin Heckman (Nov 2011) ↩

Themes and design aside, however, the relationship between this artifact of the 1980s and the twenty-first century is not straightforward. Set in a fictional 1985 that contains several costumed crime fighters and one genuine superhuman, the story tracks an elaborate conspiracy to eliminate masked heroes, ushering in a new world order where problems must be addressed by more ordinary means.This theme is a recurrent concern for Moore. An email from editor Pat Harrigan notes its appearance at the end of Moore’s Swamp Thing as well as in the unproduced Twilight of the Superheroes outline. The analogy to nuclear weapons seems clear enough, and the Moore and Gibbons emphasize it by identifying their superman as a walking “H-bomb” and excerpting a tract called Super Powers and the Superpowers (II.8.5).Citations from Watchmen refer to the trade paperback edition (Moore and Gibbons 1987), which preserves the pagination of each monthly issue. References are given by chapter, page, and panel number, using the top-bottom, left-right graph order: II.8.5 thus refers to the fifth panel on page 8 of chapter 2. Each chapter of Watchmen closes with an excerpt from a fictional document. Citations for these sections are given as chapter, “Doc,” and local pagination of the document, not the chapter: XII.Doc.1 thus refers to the first page of the document included at the end of chapter XII. Watchmen is rooted in the waning days of the cold war, caricaturing the Reagan-Thatcher axis with a Nixon administration that survives Vietnam, Watergate, and the Twenty-second Amendment to rule for seventeen years. In one of many ironic flourishes, political speculations concerning a presidential bid by “RR” point to Robert Redford; Ronald Reagan is dismissed as a washed-up cowboy actor (XII.32.3-4).

Most of its satiric targets have drifted from history’s shooting gallery, but Watchmen remains powerfully resonant with recent times. The Bush gang of Washington “humanoids” learned deceit and subversion under Richard Nixon, giving their geopolitics of oil and terror a clear line of descent from the cold war (XI.Doc.1). Watchmen’s visions of hovering airships and free electricity cut the other way, ironically counterpointing our Gotterdammerung of fossil fuels and the general decline of our not-so-superpowers. There is a passing resemblance between Tony Blair and Watchmen’s arch-antivillain, Adrian Veidt-in features, political philosophy, and some would say, morals. This seems either prophetic (Blair was after all an important political actor in the 1980s) or in the strict sense weird.

Yet such direct comparisons can only go so far. Watchmen presents an alternative history, diverging deliberately from the world we know. Tilting the prism another way, keen students of comics might thus try a different sort of thought experiment. What if our universe is the cartoon, and Watchmen’s four-color fantasy an image of higher reality? In this scheme, our recent governmental bungling might represent a Bizarro-world inversion of Watchmen’s elegant, sinister intrigues. Veidt then would not be a type of Blair but rather an antitype of George W. Bush, who seems born to the part of Bizarro Superman.

These readings are admittedly fanciful, but there is at least one point of clear convergence between Watchmen’s universe and ours. Global warming, Middle Eastern conflict, and suicide bombers do not feature in this nightmare of more innocent times, but Watchmen does include one scene of chilling currency: a tableau of New York streets strewn with bleeding corpses (XII.6.1). Within the story, this moment horribly realizes a promotion for a fitness method invented by the conspirator Veidt: “I WILL GIVE YOU BODIES BEYOND YOUR WILDEST IMAGINING” (X.13.1). Indeed he does. The bodies in question include both a cyclopean monster, purportedly an invader from another dimension, and thousands of civilians killed by a psychic blast when the phantom appears. The giant alien remains a figment of comics-or television, since its origins trace to an episode of the Outer Limits series from the 1960s (XII.28.4). The heaps of victims, terrible to say, are not beyond anyone’s imagining these days. Moore and Gibbons place their ground zero some blocks north of ours, but it is still impossible to read the final chapter of Watchmen without remembering that its lurid, apocalyptic fantasy came true, in some sense, fifteen years later.⏴Marginnote gloss2⏴Moore’s Promethea, on the other hand, is something akin to a theoretical text which gives a great deal of attention to Moore’s metaphysical views. Promethea starts as a superhero story, but quickly turns into a meditation on the relationship between reality and representation. In a way, it reminds me of Yeats’ Golden Dawn years, but without the pretension… and it offers further insight into the meaning of an under language. In Promethea, the under langauge is not simply a technique that is available to the comic book writer, but it fits with some primordial sense of what language is and what consciousness does, and models it in a manner consistent with the sort of Hermetic (“as above, so below”) view that underpins Moore’s work. Promethea also picks up on apocalyptic themes developed in the Watchmen and From Hell, but suggests that transformations don’t have to be sinister… they can be utopian, too, if we learn how the proper spells of consciousness.

— Davin Heckman (Oct 2011) ↩

If we are living on the Bizarro planet, it is possible to die there. Indeed, an especially dark resonance between Watchmen and real life arrived during the writing of this chapter. Brewing up their atmosphere of crisis, Moore and Gibbons make passing reference to the Doomsday Clock of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, part of the obsession with time and timepieces that serves as Watchmen’s white whale. In the first chapter, a newspaper headline reports that the clock “stands at 5 to 12” after the “American superman” suddenly vanishes, leaving the United States vulnerable to Soviet attack (I.18.4). Meanwhile, back in Bizarro reality, our own atomic scientists, including global warming for the first time in their deliberations, reset the clock on January 20, 2007, from 11:53 to, yes, 5 minutes before midnight (See Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists).

These days we all watch the clock, when we are not watching the Watchmen; but how can we truly understand the tenor and the terror of these times? Perhaps as Pynchon says, we have “always been at the movies,” but then again, if our world is largely a mechanical projection, the sequential narrative of cinema may not be the best way of seeing our predicament (Gravity’s 760). Comics and spatial narrative may shed more useful light.

Under Language

The medium of comics provides a powerful way to interrogate a reality abundant with signs, symptoms, and synchronicities. As noted, comics are always inherently dualistic, playing off space and simultaneity against succession and sequence. In most cases, the panel of a comic does not fill the visual field but rather coexists with others in the structure of the page. Likewise, the various verbal elements of comics (e.g. word balloons, text boxes that simulate a voice-over) impinge on the graphical surface of every panel. In developing the script for Watchmen, Moore was acutely aware of these basic properties. He notes in a 1992 interview:

What it comes down to in comics is that you have complete control of both the verbal track and the image track, which you don’t have in any other medium, including film. So a lot of effects are possible which simply cannot be achieved anywhere else. You control the words and the pictures-and more importantly-you control the interplay between those two elements in a way which not even film can achieve. There’s a sort of “under-language” at work there, that is, neither the “visuals” nor the “verbals,” but a unique effect caused by a combination of the two. (Wiater and Bissette 163)

Happily, Moore is an artist, not an academic theorist, so his concept of under-language offers a possible guide for interpretation rather than a formula for composition. As indications go, however, the idea of an under-language in Watchmen seems enormously valuable. Looking closely at the interplay of visual and verbal, and the logical and figurative structures through which it operates, can reveal a great deal about the work.

Take, for example, the first panel of Watchmen. The text box at the top contains an excerpt from the diary of Walter Kovacs, the borderline personality behind the costumed vigilante Rorschach: “Dog carcass in alley this morning, tire tread on burst stomach. This city is afraid of me. I have seen its true face.”

Watchmen panel I.1.1. 1986 DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. Used with permission.

The phrase “true face” delivers our first taste of the under-language by way of a characteristic visual-verbal pun. The words appear above a channel of bloody water that flows (appropriately enough) into a gutter, washing past a bloodstained lapel button. The button is an instance of that familiar pop culture flotsam called the happy face or smiley, and it initiates the series of significant faces-human, symbolic, and horological-that forms the main symbolic register of Watchmen. This under-language juxtaposition implicitly frames a question: Does the bloody button represent the true face of which Rorschach speaks? Various answers are possible.

Like irony, Moore’s other favorite trope, puns superimpose identity and nonidentity, setting up an array of simultaneous, contradictory readings. The face in this picture is both true and false, or a truth based on a lie. Strictly speaking, the image does not show a true face: first, because it is a minimal representation, an icon that reduces a human face to three simple marks (McCloud 29); and second, because this particular button was the sardonic emblem of Edward Morgan Blake, a costumed thug known as the Comedian, a figure whose true face (or identity, motives, or allegiances) usually stayed hidden. Then again, the moments to which this object graphically connect - Blake’s collapse just before Veidt hurls him to his death, and his anguished appeal to a former enemy a week before the murder - may indeed add up to a moment of truth (I.3.3; II.23.8). Read more figuratively, the bloody button may be a true face after all. Marked with Blake’s blood, the object does echo his actual face, slashed by a scorned woman in Vietnam, the cut approximating the angle of spatter on the button (II.14.6).In the attack (II.14.6), we see Blake from behind, with a spray of blood running across his face, projecting above the left temple, forming an angle that is similar to the blood on the smiley button (about 11:00 in clock terms). In subsequent panels (II.15.3-6), Blake’s hand is raised to his face at about the same position. Yet the scar from the wound is more ambiguous. In II.23.8, it runs across the lower part of Blake’s face, pointing to about 9:00, while in IX.23.8 it runs from mouth to eye socket, angled toward 10:00. Moral of the story: though Watchmen seems to invite an obsessive attention to visual detail, it is not after all a clockwork device. As we will see, the fact that Blake’s face carries a scar and thus lacks perfect symmetry matters more than the exact conformation of the scar. In a larger sense, a bloodstained leftover from some mindless fad, turned into the calling card of a government assassin, finally a token of his violent death, might indeed represent the true face of Watchmen’s Pax Americana: a brittle, false prosperity built on brutality and lies.

Clockwork

The search for a true face, or the face of truth, runs throughout Watchmen. Moore and Gibbons construct a densely interwoven gallery of human faces, often drawn in one-third view, dead on, looking straight at the reader, as if in intimate address - or framed for a mug shot. Nonhuman faces also matter a great deal. As we might expect from something called Watch-men, dials, clock faces, and other timepieces proliferate. Every chapter closes with the story’s own Doomsday Clock, each image placing the hands closer to midnight. Jon Osterman, the atomic scientist accidentally made superman, starts on his path when his father, a jeweler, scatters watch parts into the street, declaring the end of the Newtonian universe after reading about the theory of relativity (IV.3.6-7).

In the fatal event, Osterman is betrayed by a pair of timepieces. In 1959, he enters an experimental chamber to retrieve a wristwatch he has repaired for his fiancee, Janie Slater, becoming trapped by a time lock on the door, thus dooming him to disintegration (IV.8.2). Albert Einstein, or the collateral result of his physics, is still very much to blame. Slater’s wristwatch is smashed by a “fat man,” connecting it by allusion to the image of a blasted watch on the cover of Time magazine in 1985, commemorating the fortieth anniversary of the Hiroshima bombing (IV.6.5; IV.24.7).”Fat Man” was the nickname for the plutonium bomb dropped on Nagasaki. The Hiroshima device was called “Little Boy.” For what it’s worth, the panel preceding the fat man’s tread (IV.6.4) shows a young boy in tears.

The under-language is strong in this chain of references, and indeed throughout the fourth chapter, “Watchmaker.” Many major themes converge here: symmetry and reciprocation (the tick and tock of clockwork); desire and fatality (Osterman offers to repair Slater’s watch after they first make love); submission and dominance (Osterman’s destruction and transfiguration); and finally, time itself - or rather, a particular critique of time.

The superbeing that Osterman becomes, named Doctor Manhattan by his government handlers, exists outside mortal categories. Somehow his will and consciousness survive the destruction of his original body, enabling him to reassemble a new, heroic body by directly manipulating fundamental particles and forces. The reborn Osterman is apparently indestructible: Veidt immolates him a second time in the final chapter, but he simply reconstitutes on a larger scale (XII.14.4; XII.17.4). Along with death, Doctor Manhattan has also escaped the human experience of time. As he explains to Laurie Juspeczyk, his estranged partner: “Time is simultaneous, an intricately structured jewel that humans insist on viewing one edge at a time, when the whole design is visible in every facet” (IX.6.6).

Even without the benefit of Moore’s hints about an under-language, it should be apparent that Doctor Manhattan’s jewel-like conception of time also describes the architecture of Watchmen. All the examples we have discussed above exhibit this spatial or fractal quality in some degree. While each panel of Watchmen may not display “the whole design,” most seem to fold back against other moments in the story, making distinctions of time and sequence seem arbitrary. Chapter IV, which lays out the autobiography of Osterman, presents a series of flashes back and forward, punctuated by something like jump cuts. The under-language of comics thus works to simulate Doctor Manhattan’s unique awareness, his post-Newtonian, relativistic being in time.

This convergence of narrative and medium begs an important question: How are we to understand a story operating in jeweled or prismatic time? To recur to Manovich’s comments on comics and the logic of industrialism, what is gained by deconstructing the over-language of film and prose, reaching beyond the two dimensions available to screen and page? This peculiar way of storytelling gives access to a simultaneous, parallelistic conception that would be much harder to express in conventionally sequential media; but radical moves always imply skepticism, if not resistance. Pynchon, whose work reaches in its own way toward spatial narrative (and comics), has given us a useful parable. In Gravity’s Rainbow we meet a misallied couple, Leni and Franz Pokler, similar in some ways to Moore’s Juspeczyk and Osterman, though with different fates. Leni is given to mystical thinking, while engineer Franz prefers more linear solutions:

He was the cause-and-effect man: he kept at her astrology without mercy, telling her what she was supposed to believe, then denying it. “Tides, radio interference, damned little else. There is no way for changes out there to produce changes here.”

“Not produce,” she tried, “not cause. It all goes together. Parallel, not series. Metaphor. Signs and symptoms. Mapping on to different coordinate systems, I don’t know…” She didn’t know, all she was trying to do was reach.

But he said: “Try to design anything that way and have it work.” (159)

In many ways, Watchmen seems the true child of Leni’s mystical understanding, shot through with coincidences, parallels, and what Pynchon calls “Kute Korrespondences,” connections that point to ominous or fatal design. In reading Watchmen we always seem to be “mapping on to different coordinate systems,” through visual and verbal puns, analogies, or other agencies of association. Yet as the insistent duality of Watchmen reminds us, every Leni has her Franz, an idiot questioner who will ask what the clockwork does when we engage its mainspring - whether, once we have designed a model of jewel time, we can somehow “have it work.” Foolish though it may be, this question deserves consideration, if not a direct answer. To do this, we need to examine more closely some features of Watchmen’s remarkable construction.

Who Makes the World?

Shortly before Doctor Manhattan delivers his jewel theory to Juspeczyk, she asks why, if he is able to foresee everything that will ever happen to him, he is constrained to behave in any particular way. The superman replies that he is still a puppet of the universe, but “a puppet who can see the strings” (IX.5.4). Ever the atomic scientist, Manhattan/Osterman refers to those higher-dimensional structures that cosmologists have postulated as the basis for post-Einsteinian physics. Yet since this phrase invokes another magical pun, we are reminded of puppets and puppeteers, watches and watchmakers, and other more mechanical structures. Reaching further, as Watchmen always encourages us to do, we might also think of “the strings” as a figure for those threads or skeins of meaning that network the text, and thus of the basic geometry of Watchmen itself. What does it mean to “see the strings” in this sense?

To begin with, this point of view implies the ability to change scale or perspective, the better to appreciate local structures in a larger context. An excellent illustration of this principle comes at the end of Osterman’s interview with Juspeczyk in chapter IX, “The Darkness of Mere Being.” Disillusioned by the breakdown of his marriage and insinuations that he has caused cancer in those close to him, Doctor Manhattan removes himself to Mars, the better to contemplate the difference between a sterile, red planet and a blue one teeming with life (IX.9.1). He raises an elaborate building from the Martian sands, meaning to put humanity on trial in the person of his estranged lover. This fortress of solitude, or palace of justice, is a gigantic, abstract sculpture suggesting a deconstructed clockwork (IV.27.3, IX.4.4). At the climax of their interview, just as Juspeczyk passes the test that redeems the human race, she throws a bottle into the structure (fantastic or not, this is still a domestic incident), shattering it into a shower of fragments.

What follows is perhaps the second most impressive technical maneuver in Watchmen. As Doctor Manhattan walks out of the ruined palace to return with Juspeczyk to Earth, the perspective begins to shift, panel by panel, from a few meters above the scene to a distant point in interstellar space (IX.26.1-IX.28.3). This ambitious crane shot is reminiscent of the Charles and Ray Eames’s Powers of Ten, and even more closely, the astronomical pullback in Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris, where the camera zooms out like a rocket to reveal that an apparently domestic scene actually belongs to an alien world.At the end of Watchmen, we see an advertisement for a Tarkovsky film festival, evidently a sign of U.S.-Russian concord. The sequence is more than just homage, however, as it is shot through with crucial details.

After its tour of the planet, Doctor Manhattan’s clockwork palace has come to rest within a crater in the Argyre Planitia. This formation has a secondary impact ridge and two large boulders or outcroppings-elements that form the ubiquitous happy face. The magical quotient of this visual pun is very high indeed, as it turns out that this curious spot is an actual feature of the planet Mars, a crater called Galle, first photographed by Viking Orbiter 1 in 1976, revisited by the Mars Global Observer in 1999 (Malin Space Science Systems).I am indebted to Dennette Harrod Jr., a contributor to my Watchmen commentary site, for bringing this fact to my attention. See Dennette’s Watchmen Page. The Galle crater is not to be confused with the more debatable structure in the Cydonia region, more or less debunked by the Mars Global Surveyor. See Mars Orbital Camera Views. It is easy to imagine Moore and Gibbons’ delight in discovering this piece of areology. If a circle with two dots and a curve is the simplest, iconic representation of a face, and if this icon is in a sense a primitive element of comics art, then the Galle crater is a cosmic comic. The artist is unknown, perhaps nonexistent - and for Watchmen at least, this uncertainty is very much the point. As Doctor Manhattan muses, watching his Martian palace rise from the sands, “Who makes the world?” (IV.27.3). We might also frame a slightly different question: If a pattern forms on a dead planet, when does it become a face?

Leaving theology and metaphysics aside, we should notice an important difference between astronomical data and artistic rendering. Moore and Gibbons have fiddled the proportions: crater Galle is 215 kilometers across, or about the distance from Washington, DC, to Philadelphia, at which scale we would not be able to resolve both human figures and the boulders that form the eyes (IX.26.5). More significantly, they have added the smashed remains of Doctor Manhattan’s flying palace, which does not correspond to anything in the actual crater. In their depiction, the wreckage lies just southeast of the right-eye boulder, thus echoing with only slight variation the Comedian’s bloodstained button.

The first resonance of this image is local, climactically closing the ninth chapter with a visual power chord. Doctor Manhattan decides to avert a possible nuclear holocaust after Juspeczyk unwittingly reminds him of the miraculous improbability of human life. The crater beautifully symbolizes this primal accident: a highly unlikely arrangement of inert matter into an echo of that other sublime accident (or if you prefer, divine design), the human face. In an odd way, the dead, red world has produced an image of life - or an emoticon, at least.

At the same time, though, the discovery of this image resonates in other ways as well. As an ordinary human, Juspeczyk cannot see the larger pattern of which she is a part, even though she determines at least its final stroke, first by refusing to fly further, causing Doctor Manhattan to land at Galle, and then by smashing the palace where it stands (IX.22.1). Both actions are impulsive and entirely unplanned - “thermodynamic miracles,” to echo Doctor Manhattan’s description of humanity (IX.21.9). As a superman, he is capable of both astronomical views and grand architectural gestures, but there is no indication of either in this moment. When he and Juspeczyk vanish from Mars, they reappear on Earth, so the cosmic crane shot on the chapter’s final pages does not represent their point of view. (It probably prefigures Doctor Manhattan’s departure at the end of the story, but this is mapping to another system, in every sense.) In effect, the perspective of the final sequence belongs only to the reader and the authors. Reading the under-language of comics, we see what the characters do not or cannot; but what exactly do we see?

Watchmen panel IX.27.1. 1986 DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. Used with permission.

Taking the Galle tableau at (unavoidably) face value, the scene would seem to signify completeness or perfection of symmetry. As the characters agonize about the possibility of meaning, they walk through a gigantic design that is both highly significant and entirely accidental. Watching the watchmen, we close the circuit of irony between authors and reader. We also witness an act of inscription: Juspeczyk’s destruction of the palace has quite literally graphic consequences. In terms of its own semiotics or under-language, Watchmen thus inscribes its primary icon on itself, setting up a resonant, self-referential sign system, a kind of standing wave or feedback loop. This episode of visual noise rings true. Even accident produces pattern, and when humans come on the scene, pattern becomes meaning. Delivering this message, art confirms its function. Beauty is truth, and life goes on. The pendulum of uncertainty, oscillating between extinction and survival, red Mars and blue Earth, ticks back again, duly reciprocal. Even the planet smiles.

This all-too-easy reading, however, neglects at least one crucial detail. To complete the grand design, Juspeczyk must shatter the crystal palace, reducing its elegant architecture of cups, wands, and wheels, with its meticulous fourfold balance, to a jumbled heap of fragments. In creating the larger, unseen pattern, she destroys the one at hand, wrecking its harmonic arrangement. Notably, she must also disrupt the larger symmetry of the original scene: by adding a fifth stroke to the design, the fallen palace defaces the face on Mars. This more complicated reading reminds us that noise or entropy are as important in Watchmen as integrity of signal. The under-language of this work contains more than puns, ironies, echoes, and other reciprocating structures. It also encompasses flaws, fissures, gaps, gutters, and other limits to design.

Everything Balances

We can find the most compelling demonstration of this fact in the remarkable chapter V, “Fearful Symmetry,” structurally speaking the most impressive part of Watchmen.My treatment of chapter V owes a great deal to Jessica Furé’s reading, which she developed in a research project undertaken with me in 1999. Her essay “Why Five?” is available as part of Watching the Detectives. As the title suggests, the chapter is filled with doubles, mirrorings, echoes, and dichotomies. Its main subject is Rorschach, a masked marauder whose costumed face is an ever-changing inkblot. Like many comic book heroes, Rorschach leads a double life, maintaining a secret identity as Walter Kovacs, a sometime mental patient and self-appointed prophet of doom (I.1.3). In much more than name, Rorschach is deeply linked to Watchmen’s symbology. At one point we watch him idly deface a menu in a diner, pouring ketchup on to a page, and then folding it over to create a symmetrical stain (V.11.7-9). As we will see, this reference to patterns on folded pages has more than momentary or local significance.

Chapter V abounds with indications of doubleness. The main narrative begins and ends outside a bar called Rumrunners, whose emblem, a pair of mirrored Rs integrated into a stylized skull and crossbones, constitutes a double visual echo (V.1.1). It recalls the traditional flag of piracy, and hence the comic-within-a-comic Tales of the Black Freighter, introduced in chapter III and further developed here. At the same time, the mirrored Rs of the bar sign echo Rorschach’s signature (V.3.9). Since Moore and Gibbons never do their doubling by half, we first see this emblem as a reflection in a puddle, taking us deeper into the hall of mirrors.

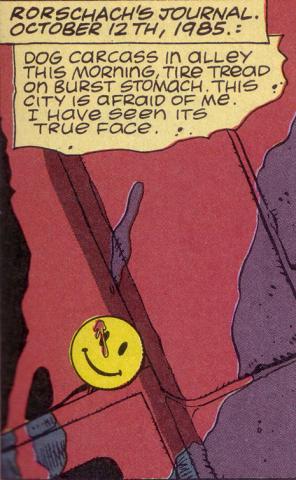

Both the theme and the structure of chapter V participate in this system of echoes. As he hauls Rorschach away at the end of the episode, a police officer notes that the “terror of the underworld” will be locked up with the men he hunted: “Everything balances,” the detective says (V.28.8). This statement may not be entirely accurate but is certainly salient on many levels-including, for chapter V, the material structure of the text itself. The 220 panels and twenty-eight numbered pages of chapter V form a graphic palindrome, a kind of comic as inkblot. On each side of the chapter’s seven signatures, the division of panels on the left-hand page mirrors the arrangement on the right. Page one mirrors page twenty-eight, page two mirrors page twenty-seven, and so forth.This scheme implies relationships between the panels of corresponding pages. Jessica Furé and I developed a browser for juxtaposing paired panels, and notes on some of the more interesting correspondences. The effect is literally half-concealed. Fourteen pages use a regular, three-by-three grid, and so offer no immediate clue to the scheme. Interspersed throughout the chapter, the other fourteen pages vary the regular grid, revealing their relationships more readily. On page nine, for instance, the basic nine-panel page is cut down to six by stretching panels one, four, and five to double width. Page nine is eight pages from the beginning (1 + 8), so its mirror correspondent is eight pages from the end, page twenty (28 - 8). On that page, the doubled panels are two, three, and six, reversing the geometry of page nine. Of course, the most striking evidence of the palindrome falls at the center.

Any palindrome implies a crossing point or chiasmus where orientation reverses. The center spread of chapter V constitutes this structure, especially the cardinal panels (V.14.2 and V.15.1). Chiasmus comes from the Greek letter chi, which gives us the Roman X. X indeed marks the spot where opposites converge and “everything balances,” ostensibly at least. The X is formed by the golden V from Veidt’s corporate logo and the two clashing bodies, Veidt at the left, and his hapless would-be assassin at the right. Veidt’s leg makes up his side of the X pattern, while the assassin’s upper body provides the opposite. Veidt swings his improvised weapon in an arc traversing the upper three-quarters of the image, while the assassin falls in a complementary arc below. The object, evidently an ashtray in the style of an Egyptian urn, is convex at the left, and concave at the right. In the lower quarter of the image, an upright golden head at the left (a dead king) mirrors the inverted face of the killer at the right (a doomed fool), and both are reflected in the fountain pool below, yet another plane of symmetry.

Watchmen panel V.14-1. 1986 DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. Used with permission.

In more than one sense, these panels represent the heart of a hall of mirrors, since what we seem to witness here-Veidt’s miraculous escape from a murder attempt, evidently part of the conspiracy against costumed heroes-is an elaborate falsehood, a piece of brutal theater concocted by Veidt to hide his true purpose. The crossing point consummates a double-cross. It would follow, then, that the apparent perfection of symmetrical design is deeply suspicious, and in fact, there is something wrong with this picture. A duly sensitized reader might notice at least one asymmetry, with two horrified onlookers standing at the left and only one on the right. The right-hand figure is a letter carrier (again, in several senses), and on his bag we can make out the characters “US” and “AIL” - suggesting perhaps that something in this scene reveals what in Watchmen’s world might ail us. Admittedly, another reading is possible: what ails us microscopic analysts may be a strange compulsion to read comic books with a 3 × lens. In our defense, Harrigan wisely points out that Moore seems to encourage, if not require, this sort of paranoiac view. Watchmen contains a vast number of minute but significant details, and anyone who doubts their intentionality should glance at one of Moore’s scripts, where he often takes several paragraphs to specify a single panel. See, for instance, the excerpted script for chapter I included in the Absolute Watchmen, or From Hell: The Complete Scripts, Book One. Those who have seen the ending know the culprit is Veidt, but his megalomania might raise concern even for an obediently serial, first-time reader. On the next page we see him apparently find (actually plant) a poison capsule in the mouth of the stunned assassin, and then at the end of all the carnage calmly ask an employee to “call the toy people” and cancel a line of action figures (V.16.9). To Veidt, the genius antivillain, humanity is made up of “toy people” who need his attentions. Like the duped assassin in the central scene, or like Rorschach, framed for Edward Jacobi’s murder at the climax of chapter V, everyone is caught in the elaborate structures of Veidt’s plot.

At a later point in the story, Veidt will tell Dan Dreiberg, the hapless Nite Owl, that he is “not a Republic serial villain” (XI.27.1). He means that he has revealed his masterstroke only after it is complete, and the costumed crusaders actually are, as Pynchon says, “My God … too late” (Gravity’s 751). But another sense of serial also operates here: Leni Pökler’s dyad, “parallel, not series.” Veidt is indeed a nonserial villain. He bases his heroic identity partly on Alexander of Macedon, whose “lateral thinking” defeated the Gordian knot (XI.10.2). He uses a method of planning derived from William S. Burroughs’s cut-up technique and takes as his oracle an array of television screens (visually, of course, an analogue of the comics page, and thus of spatial narrative) (XI.1.1-XI.2.4).

Though Veidt is a meticulous cause-and-effect man and a hell of an engineer, his conspiracy ultimately owes as much to Leni as to Franz. The plot is an elegant, nefarious arrangement of “signs and symptoms.” Nonetheless, it would appear that he does “have it work” - or as Moore and Gibbons quote Shelley: “Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair” (qtd. in XII.28.14). At least on first inspection, the irony of Shelley’s poem, where the boast is inscribed on ruins and emptiness, seems reversed. Veidt is successful, and his works reshape the world. By the final chapter, he has managed to outwit his human adversaries, Dreiberg, Juspeczyk, and the resurgent Rorschach. He tries first to deceive, then to destroy Doctor Manhattan, and though he fails, he does force their contest to a draw. “What’s that in your hand, Veidt,” the reintegrated Doctor Manhattan asks derisively, “another ultimate weapon?” (XII.8.4). The object in question is the remote control for Veidt’s video wall, now showing news accounts of his deadly attack on New York. Evidently his phony alien invasion has forced the United States and the USSR to retreat from the nuclear brink-hence the little gadget does stop the superman in his tracks.

Veidt creates an artifice of meaning that becomes the true face of Watchmen, an image of official happiness stained with blood. The “ultimate weapon” is information or persuasion: an appeal to map the world situation on to new coordinate systems and recognize the necessity of that arrangement. Facing the end of the end of the world, yet apparently still committed to humanity’s survival, Doctor Manhattan must enlist in the deception, even to the point of homicide; so he confronts the implacable Rorschach, who intends to reveal Veidt’s murderous fraud. “Evil must be punished,” Rorschach insists (XII.23.4). Doctor Manhattan levels his omnipotent hand, Rorschach urges, “Do it!”, and the “judge of all the earth” blasts him to bits, leaving one last smear of blood (XII.24.3, XII.24.4-5). In another email note from Harrigan, he writes, “I can’t resist mentioning issue 17 of Denny O’Neill’s The Question where the Question (on whom the character of Rorschach was based, of course), picks up a copy of Watchmen and reads it on a flight across the country. He falls asleep and has nightmares about dying in the snow, like Rorschach. Naturally, at the end of the issue he finds himself at the mercy of some killers in the middle of a snowstorm, and flashes back to Watchmen, before Green Arrow arrives to save him.”

It would appear, then, that everything balances. Americans and Russians stand down from Armageddon. Veidt is left like a happy spider at the center of his new world order. Having silently blessed the union of Juspeczyk and Dreiberg, Doctor Manhattan removes himself to a distant planetary system, evidently planning to create life - this after facing Rorschach, his final adversary, and granting his wish for death. Tick, tock.

Five to Twelve⏴Marginnote gloss3⏴The film version of Watchmen, directed by Zack Snyder, was released in 2009. ↩

On closer inspection, though, this great clockwork displays a suspicious hitch or wobble. Just as Doctor Manhattan’s will defies disintegration, Rorschach leaves a testament that survives his messy death. Before he and Dreiberg set off to confront Veidt in Antarctica, Rorschach mails his journal to the “only people [he] can trust,” a reactionary, anti-Semitic rag ironically named the New Frontiersman (X.22.5). A few pages later, we see Rorschach’s book arrive, at which point the editor, Hector Godfrey, tells his plodding assistant Seymour to add it to the “crank file,” where it is buried in an “avalanche of drivel” (X.24.4-9). The term avalanche is telling, since such structures tend to collapse, smashing everything in their path, and the metaphor may be apt. At the time he dispatches his journal, Rorschach and Dreiberg have accumulated enough evidence, particularly financial and business records, to raise serious, perhaps fatal questions about Veidt. True, Dreiberg and Juspeczyk, the only living witnesses to Veidt’s confession, have absconded under new identities at the end of the story; but mention in Rorschach’s journal would presumably make them subjects of speculation and maybe even pursuit. In short, Rorschach’s posthumous testimony can at least potentially unweave all Veidt’s machinations.

These possibilities converge in the final panel of Watchmen, which we will consider presently. First, however, we need to explore one more crucial feature of the under-language in chapter V, an essential precondition for that final stroke. We have discussed in some detail the internal structure of the chapter, but something needs to be said as well about the way that structure relates to the larger scheme of the work.⏴Marginnote gloss4⏴Take a look at M. Wolf-Meyer’s “The World Ozymandias Made: Utopias in the Superhero Comic, Subculture, and the Conservation of Difference” in The Journal of Popular Culture 36.3 (Mar 2003). Wolf-Meyer discusses the restrained nature of the superhero relative to their superpowered abilities. In a way, I think this argument might resonate with some of the radical possibility that is open to us in the digital age. We have free reign to generate representations with great range, reach, and capacity, but they must subsist on some terrain of intelligibility. Wolf-Meyer discusses this from a Marxist perspective.

— Davin Heckman (Oct 2011) ↩

Viewed from outside the chapter (from orbit, as it were), the double-crosser’s cross at the middle of chapter V seems oddly placed. As a matter of fact, the entire chapter may be mislocated, if we assume that a palindromic comic makes a natural pivot or bearing for a structure of bilateral symmetry. The midpoint of a twelve-part epic falls in the gap between the end of the sixth part and the beginning of the seventh. Of course, this makes the graphical chiasmus of chapter V formally impossible, so clearly Moore and Gibbons had to break some rules to accommodate their ingenious design. Other decisions seem possible, though, such as locating the palindromic chapter in the sixth or seventh position, or creating a matched set of mirror chapters in both positions. Why choose the fifth chapter for a tour de force of symmetry?

For the author of V for Vendetta, and a keen reader of Pynchon’s V., the temptation to play some variations on the fifth Roman numeral may have been too hard to resist. The development from the V of Vendetta to Veidt, the Mr. X of Watchmen, does seem resonant. One careful reader points out that chapter V constitutes the midpoint of the ten-chapter sequence where Rorschach compiles his journal, detailing the events leading up to the cataclysm in New York (Furé). This interpretation makes some sense, especially considering the V-into-X symbolism, which invites attention to the numbers five and ten. Yet as Jessica Furé points out, the middle of a ten-part series comes between five and six, not midway through five. If we insist on reading with scientific precision (not the only way to read, of course), it seems clear that the strongest image of centrality and symmetry in Watchmen is out of alignment. The chiastic center spread of chapter V sits at an awkward point in the timeline, throwing the entire structure of Watchmen off balance. To paraphrase Pynchon: My God, we are too early!

On the other hand, perhaps the fateful symmetry of chapter V is right where it belongs, in precisely the wrong place. The brilliant artifice of the palindrome chapter does not integrate into a grand design but rather disintegrates, or in the strict sense deconstructs that design, opening up its artifice for critical understanding. Chapter V might be understood as an image of Veidt’s plot, an attempt to create a universal balance that cannot succeed because it is subsumed by a larger principle of chaotic flow. Thus we refute Franz Pokler: it is less important to see how the clockwork operates than to know how it fails.

See the Strings?

At the end, then, we have to wonder whether the under-language of Watchmen can truly deliver an image of Doctor Manhattan’s jewel time. Perhaps we are left less with an image than a model, a structure subject to testing or experiment, and perhaps the point of this experiment is to observe that model’s failure. Like Doctor Manhattan’s crystalline judgment seat, smashed into signifying wreckage in the Galle crater, Veidt’s plot also seems poised for collapse in the last panel of Watchmen.

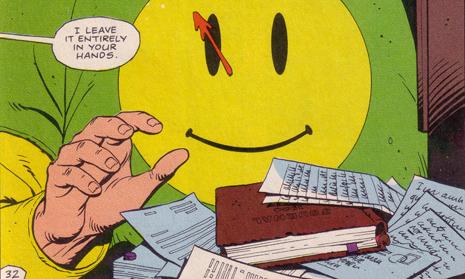

Predictably enough, a work that started with a visual-verbal pun ends on the same note: Godfrey’s exasperated outburst, “I leave it entirely in your hands.” As it is in the beginning, the under-language here is deeply ambiguous. Literally, Godfrey’s statement is true enough. He tells Seymour to choose something from the crank file to fill a hole in the upcoming issue. Since the truly ultimate information weapon is now on top of the stack, Godfrey has placed the fate of Veidt’s illusion, on which humanity entirely depends, in Seymour’s unwashed hands.

Watchmen panel XII.32.7. 1986 DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. Used with permission.

At the same time, though, there is a strain of inversion or irony in this final line of Watchmen. Though the sequence implied here is formally incomplete - we never see where Seymour’s hand comes down - the deck is stacked (or the stack is decked out) for revelation. Rorschach’s notebook is rendered in full color and detail, so that we can see the book tape inserted two-thirds through, presumably marking the last journal entry. Other elements of the pile are sketched in, suggesting they are not in focus, and inked in blue to indicate they lie in shade. In the near background, the inevitable stain on Seymour’s smiley-bedecked jersey also points decisively toward the book, or if you read its arrow shape the other way, over Seymour’s shoulder into the unwary world. Finally, if we consider the name of our numinous decider, the public can probably expect to See More than it does at present - perhaps more than is good for it.

Reading the last panel as overdetermined in this way reasserts at least one aspect of reciprocation, if not balance: the swinging pendulum of sequential time. Perhaps what we have here, though, is not so much the ticking of a clock (tick-tock) as of a bomb (tick-tock-BOOM). This reading is inescapably fatalistic, nihilistic, or perhaps in a terrible way, realistic. Veidt’s plot staves off an imminent nuclear war, so dismantling its artificial detente raises the likelihood of renewed conflict and perhaps the end of civilization. Read in this way, Watchmen is an enormously tragic comic.

Consider its ultimate symbol or icon. The stain on Seymour’s jersey, ketchup now, not blood, concludes and summarizes a series of repetitions, from the blotched button of the first panel through various coy echoes of the stain shape (e.g., XI.1.2, XI.28.12) to the defaced face on Mars. This is, finally, the true face of Watchmen’s city of heroes: a bright circle of devious contrivance, blotted with blood, trauma, and the emergent catastrophes that beset all complex systems. It is the emblem of a clockwork that slips a gear, a broken symmetry that fails to encompass its world.

Yet as we have seen, most signs and statements in Watchmen have two or more senses, infused by the essential field of allusion and irony that permeates the work. So the signature image or true face of Watchmen also stands for the miraculous catastrophe by which order, consciousness, and meaning emerge from chaotic flux. Bending the light this way through Watchmen’s intricate prism brings a different view of the last panel. If the entire structure of this epic comic is in some way experimental, then we can take the final panel as an ultimate observation. As the second-person address in the last line hints, the subject of this test is the reader, or “you.”

Read as final exam, the last panel poses a deceptively simple question: Can you see the strings? That is, can you understand the under-language of this comic, and of comics generally, sufficiently to recognize the artifices at work here? More crucially, can you also hold those artifices in suspension? Learning from chapter IX about the enlightening effects of scale change, and from chapter V about the relationship of local structures to global, we might remember that every panel belongs to a larger pattern, and that it may not complete that pattern but rather disrupt it. Even though so much in Watchmen’s final measure points toward apocalyptic unveiling, it does after all fail to conclude the act. If McCloud is right about visual closure, then the grammar of comics depends on our ability to infer context from fragmentary images of actions, so here we have one final case of Moore and Gibbons running around with their under-language on display. At the same time, there is a literary reference here, to the unfinished business at the end of The Crying of Lot 49, which leaves the status of the Tristero system permanently unresolved. Seymour’s hand has not come down. Strictly speaking, it never does. Looking with educated eyes, we may detect details and arrangements that foreordain an outcome - cosmological strings, puppet strings, or chains of under-language-but we who watch the Watchmen stand outside them.

Read this way, the iconography of the final panel depends not so much on the ominously illuminated book, the final evocation of the world’s true face, or even Seymour’s fatally outstretched hand. What signifies most is the emptiness of that hand, and the fact that the book of final judgment remains shut. Watchmen ends with an image of its own medium, a bound volume, seen from outside, arrested at the moment before irrevocable conception, in spite of all strings visibly attached. It thus gives a symbolic signature for a liminal or interstitial relationship to objects of communication, a way of seeing and reading that does not hide the strings.

In Your Hands

Interstices are inherently awkward places. Those who haunt the gutters tend to look toward the stars or those places where stars gather. As sequentially time-bound animals, denizens of a postindustrial culture still heavily conditioned by linear processes, we do not take easily to spatial narrative. Seeing the strings comes hard, and sometimes you just want to watch something.

We do not lack for choices. The television series Heroes is now well into its second season, weaving tropes and themes of Watchmen into a new context that speaks particularly to these post-traumatic times. The Trade Center site of actual disaster is now flanked symbolically not just by Watchmen’s Institute for Extraspatial Studies, but by Kirby Plaza as well, another gathering point of pattern and coincidence, not coincidentally named for the great comics master. Tim Kring has even shown us his own version of the strings, in the three-dimensional model of convergences found in Isaac Mendez’s apartment.

Meanwhile, a film version of Watchmen is once again in preproduction, the most recent of several attempts to bring Moore and Gibbons’ work to the screen. Moore is notoriously disdainful of Hollywood, refusing to let his name be used in connection with film versions of his comics. He reputedly told the director Terry Gilliam that the best cinematic treatment of Watchmen would be none at all (Wikipedia). The reasons for this antipathy are best known to the author, though seeing a work with the scope and nuance of From Hell turned into megaplex fodder certainly does not help. When you read this, you may be able to judge whether the film version of Watchmen fell closer to genuinely interesting inventions like Batman Begins or to vapid star vehicles like The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. Then again, history may record yet another failed project, leaving Watchmen among cinema’s greatest stories never told.

In some ways, that last outcome would be appropriate, however it might diminish the canon of comics films. No sequential medium - not cinema, not print, and certainly not the sort of print that makes up a scholarly essay - can do full justice to the under-language of Watchmen. As indicated, this comic delivers not a working timepiece but something more like a catastrophe simulator, an open-ended experiment that the reader is invited or expected to perform. Understanding Watchmen in this light makes it seem distinctly avant la lettre, something impossible to describe in traditional terms. More than the relic of an older, spatial way of seeing, it prefigures and perhaps inaugurates the next thing in sign systems.

In this century we are beginning to build on our technologies of recording and inscription new media and new language that operate by systematic simulation. We deal less in simple arrays of signs than in sign systems that do not simply store but actively produce and modify meaning. Thanks to instrumentalities like the Web and Google, this change increasingly affects even the most traditional communications. These innovations demand many changes of mind. To acquire the new language, we need an ability to map across multiple coordinate systems, an awareness of contingent or emergent forms, and a keen appreciation of the limits to any neat, self-enclosing order. We must see the strings in many senses: as patterns of association, multilinear paths, and the under-language of database structures, lines of code, and visual presentations. This is by no means easy work, and the magnitude of the change is so great that we tend to engage it only at the limits of awareness, in odd cases and ostensibly minor forms.

As a masterpiece of its particular, invisible art, Watchmen bears in a major way on our moment. Its nightmare of bodies beyond imagining may have come true in post-9/11 history, but at the same time, so has at least one analogue of its hyperconnected, deeply intertwingled worldview - as every website devoted to Moore and Gibbons’ work attests. Living as much in the future as on Bizarro World, we pass naturally enough from the pages of a self-deconstructing comic to hypertexts, wikis, and other forms that both reveal the strings and make them ready to hand. If Watchmen did not literally anticipate Internet culture, it provides a structure, and some crucial lessons in structural inquiry, that may be of great help in understanding its underlying media. In an important sense, we must make our world, and reading Watchmen may help us live up to the task.

Works Cited

Benkler, Yochai. The Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom. New Haven: Yale UP, 2007. Print.

Furé, Jessica. “Why Five?” Watching the Detectives: An Internet Companion for Readers of Watchmen. University of Baltimore, 4 June 1999. Web. DATE OF ACCESS. http://iat.ubalt.edu/moulthrop/hypertexts/wm/readings/fearsym/comments.htm

Johnson, Steven. Everything Bad Is Good for You: How Today’s Popular Culture is Actually Making Us Smarter. New York: Riverhead, 2005. Print.

Joyce, Michael. “Siren Shapes: Exploratory and Constructive Hypertext.” Academic Computing, November, 1988: 10+.

Manovich, Lev. The Language of New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002. Print.

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. New York: Harper Collins, 1994. Print.

Moore, Alan. Absolute Watchmen. Illus. Dave Gibbons. New York: DC Comics, 2005. Print.

---. From Hell: The Complete Scripts, Book One. Illus. Eddie Campbell. Baltimore: Borderlands Press, 1995. Print.

---. Watchmen. Illus. Dave Gibbons. New York: DC Comics, 1987. Print.

Moulthrop, Stuart et al. Watching the Detectives: An Internet Companion for Readers of Watchmen. University of Baltimore, November 2000. Web. DATE OF ACCESS. http://iat.ubalt.edu/moulthrop/hypertexts/wm/

Pynchon, Thomas. The Crying of Lot 49. New York: Harper Perennial, 2006. Print.

---. Gravity’s Rainbow. New York: Viking, 1973. Print.

Wiater, Stanley and Stephen R. Bissette. Comic Book Rebels: Conversations with the Creators of the New Comics. New York: Plume, 1993. Print.

Cite this essay

Moulthrop, Stuart. "See the Strings: Watchmen and the Under-Language of Media" Electronic Book Review, 12 October 2011, https://electronicbookreview.com/publications/see-the-strings-watchmen-and-the-under-language-of-media/