“the many gods of Mile End”: CanLit Print-Culture Nostalgia and J.R. Carpenter’s Entre Ville

Carl Watts argues that J.R. Carpenter’s Entre Ville constructs Canadian literature as a unified, holistically understood entity that is both broadly accessible and fleetingly familiar. In so doing, Carpenter’s work aligns representations of Montréal with uses of new media, with the cross-cutting and mutually exclusive identities of the former mirrored in new-media poetry’s partial or conditional embrace of the formal possibilities of digital poetry.

While Canadian poets have made forays into digital writing,1 one could be forgiven for questioning whether there is an identifiably Canadian substrate of new-media poetry. bpNichol, whose First Screening (1984) seems somehow as influential as it is sui generis, is one option. Still, the work is of a piece with Nichol’s other work, which ranges wildly across and between genres and formats; Nichol is a shapeshifter, or possibly something like Canadian poetry’s William Gibson - a technology-obsessed weirdo who, although partially or coincidentally Canadian, is identifiable more as someone who jacks in to the cyberspace of Neuromancer (1984) than as a resident of any Canadian province.2 And yet, as recent scholarship suggests, even some seemingly radical new-media poetics are conceived entirely within the print-bound forms and cultures that predated them. As I will argue here, distinctly Canadian iterations of digital poetics are not only increasingly identifiable, but specially positioned to explore the traditionalism inherent in mainstream conceptions of literature, literary culture, and cultural production - including most especially parallels between Montréal literature and new-media literature. Specifically, I want to suggest that an increasingly commented upon Canadian work of mid-2000s new-media poetry - J.R. Carpenter’s Entre Ville - presents an accessible and conventional image of Canadian literature in order to at once indulge in and critique nostalgia for a print-based literary culture. What is more, the tentative or partial embrace of the digital that constitutes its form, combined with experiences and representations of Montréal that address the outsider while also underscoring the partial or conditional nature of this inclusion, reflects the incorporation of singular, complex literary scenes into both mass national print economies as well as the subsequent adaptation of the latter to an increasingly digital literary economy.

Scholarship on the new-media poetics that was emerging circa Entre Ville’s appearance in 2006 3 tends to comprise either radical arguments regarding the expanded formal possibilities of such media or else cautious explanations of these works’ continuity with text-based culture, knowledge, and practices. Examples of the former include N. Katherine Hayles’s works, some of which reflect in their form the extent to which our most deep-seated assumptions about print culture and literature are radically situated in outmoded technologies,4 as well as Adalaide Morris’s location of the new media poem in an “expanded field” encompassing both poetry and non-poetic forms (19). More circumspect critics include Daniel Punday, who argues that new media literature “remain[s] bound to the limits of writing” and, particularly, the novel (155). Jessica Pressman contends that second-generation digital literature offers a “surprise counterstance” to the obsessions with novelty that often characterize digital culture, exhibiting instead a “commitment to literariness and a literary past” (2). Similarly, Daniel Morris argues that a “cusp” generation of writers - those who came of age before the digital era and subsequently adapted to it - employ an “art of the in-between,” working in an ambiguous space “that is a lyrical expression of an idiosyncratic response to personal traumas and political upsets and a documentary treatment of a wider social text composed primarily or exclusively from resources not designed by the author’s own hands” (18). Morris most explicitly contends that new-media poetics is notable precisely for its failure to represent a radical break with print literature - a multivalent and generative limitation that, as I will argue below, exists in Entre Ville.

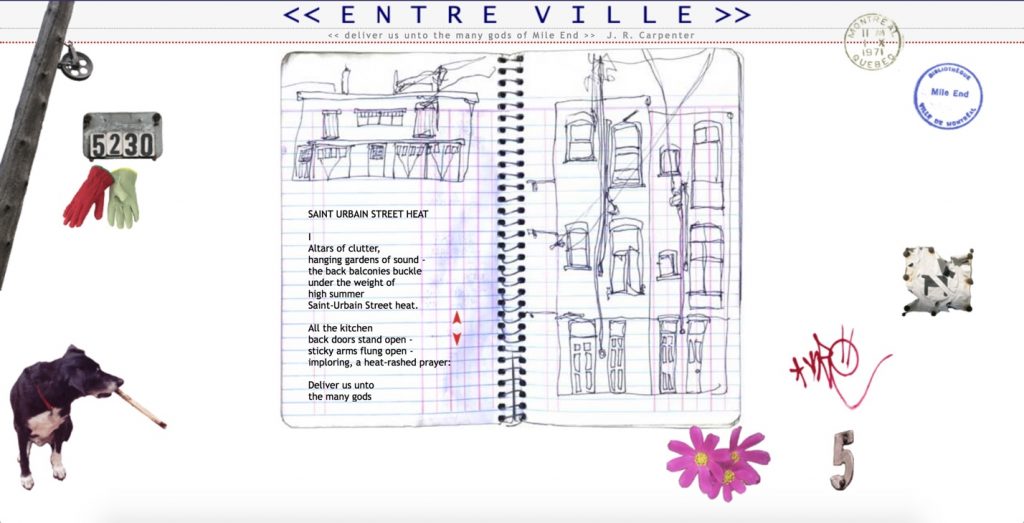

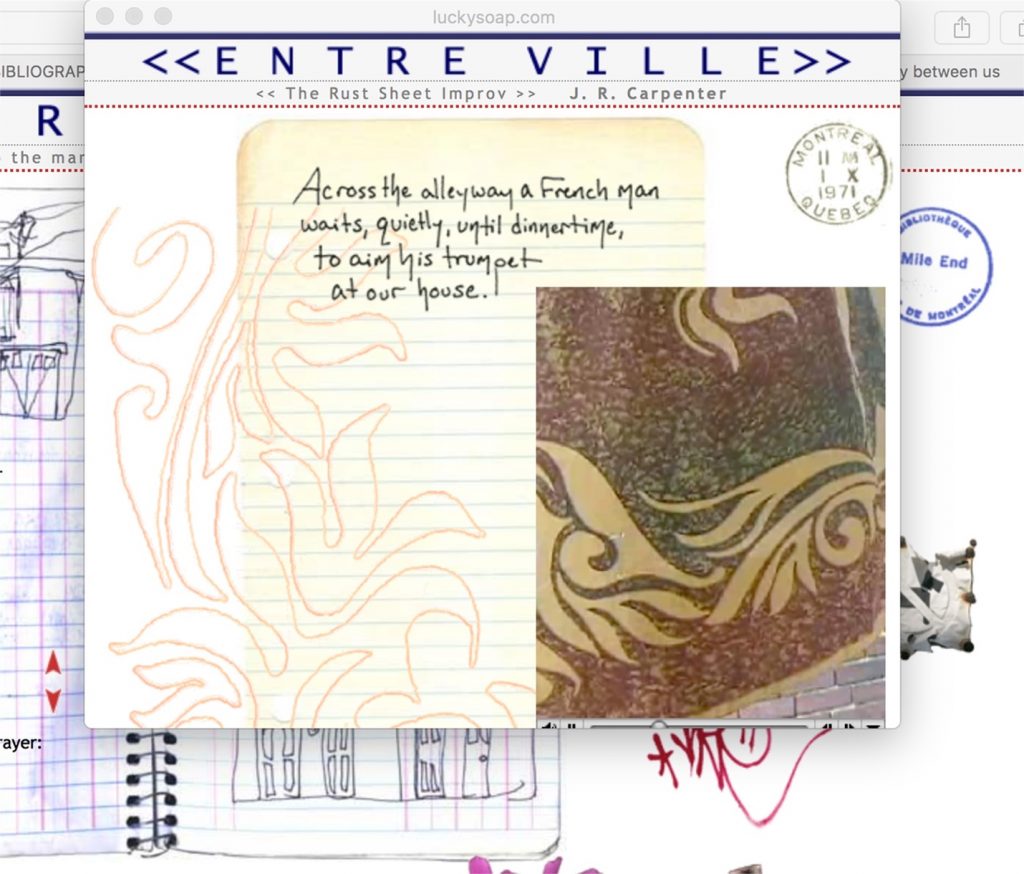

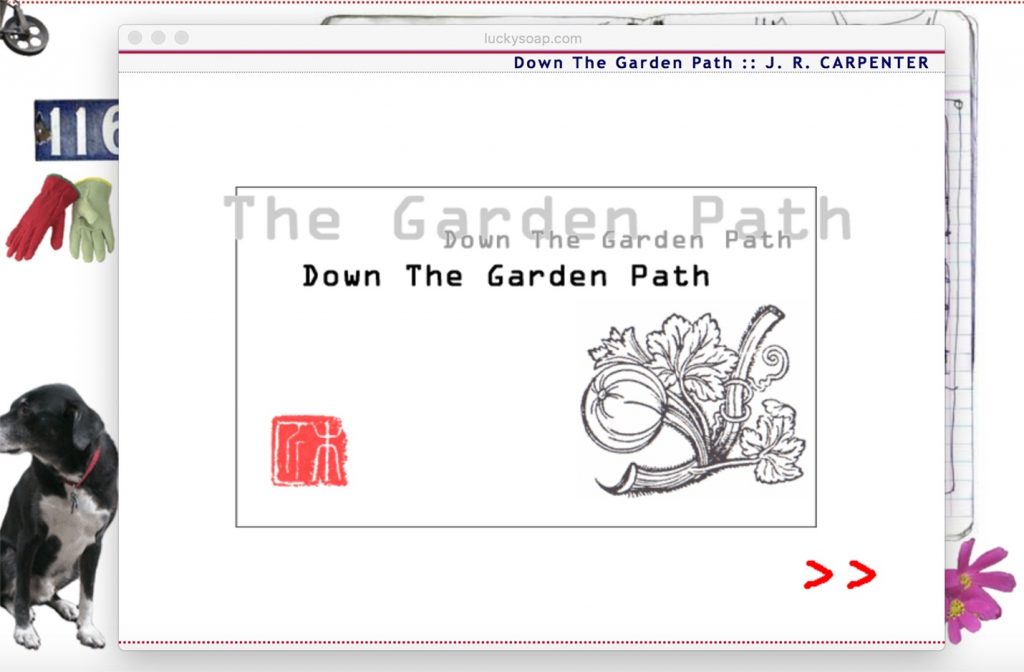

Different aspects of Entre Ville reflect both this sense of possibility and the tendency of digital forms to mimic or be constrained by print-based forms and ideas. The piece is built around a user interface that features a graphic of a spiral notepad in the center; the left page features a conventional eight-stanza poem (guided by a scrolling mechanism), and the right page depicts a sketch of a three-story residential building typical of Mile End and many other Montréal neighbourhoods (Fig. 1). Guiding the cursor over the notebook reveals that several of the building’s windows change color; clicking any of these spots opens a new browser window within which is a short video clip depicting a Mile End alleyway landscape (Fig. 2). Clicking other items surrounding the notepad reveals additional features: selecting the dog in the bottom-left corner converts the left notepad page from “St. Urbain Street Heat” into a prose piece called “Sniffing for Stories”; choosing the nearby pair of gloves uncovers a new window containing a click-through narrative called “Down the Garden Path” (Fig. 3). Meanwhile, a postmark in the top-right corner reveals a direct email link to Carpenter, and a second displays links to three supplementary texts: “A Mile End Bibliographie”; «entre guillemets»; and «this city between us», a description of the genesis of Entre Ville.

Entre Ville is radical in that it draws from visual art, ambient video, conventional poetry and prose, and, with “A Mile End Bibliographie” and «entre guillemets», both print-based and digital bibliographies. It is also difficult to categorize in terms of genre or situation in the academy’s disciplinary taxonomy. In addition to the question of whether it ought to be considered poetry or visual art, Carpenter’s transnational backstory - the artist is from rural Nova Scotia, frequently visited New York City while growing up, and lived in Montréal throughout the 1990s and 2000s before relocating to England5 - further complicates its inclusion on university syllabuses, many of which continue to be organized according to authors’ national affiliations. It thus evokes Adalaide Morris’s expanded field not only in its form but in its reflexive relationship with the architectures determining the circulation and consumption of texts; Punday refers to it as “embrac[ing] rather than suppress[ing] the tension between the media that make up an electronic text” (200). And Carpenter, born in 1972, also fits the age range Daniel Morris demarcates. For this reason and because of the abundance of print-culture techniques and references that characterize Entre Ville, the work appears to fit Morris’s framework quite well.

More recently, Scott Rettberg describes Carpenter’s work as an example of hypertext fiction in which “densely layered, collaged visual interfaces” nevertheless “supplement the written narrative” (ch. 3). Regarding Entre Ville in this way - in the lineage of hypertext and with a written narrative as central - gives credence to Dani Spinosa’s contention that digital Canadian literature’s reader-engaging elements complicate the authority of authors as well as editors and publishers, “gradually affording more authority and power to its readers by way of engagement, connection, and privileging of the affective nature of addressing and attending to the needs of readers” (240). But it also reminds us that this dynamic exists within a framework that is informed by past conceptions of publishing and mass literary culture as well as the ongoing adaptation of these formations to recognizable market conditions. Entre Ville therefore points to the potential described by Spinosa while also identifying and lightly critiquing the commodification and standardization of literary economies and the concomitant limitations in the histories and architectures that structure conceptions of readership.

Accordingly, I suggest that Entre Ville is marked by neither excessive optimism about the possibilities of the digital nor any unproblematized reverence for print. It invokes the in-betweenness Daniel Morris finds in much work by the not-born-digital set, but Carpenter’s poetics further synthesizes dual registers of lyrical response and objective documentation. The work locates lyric response within an affective complex that has already emerged from both a print-culture history and, in the form of its listing as metadata (in “A Mile End Bibliographie”), in the digital technologies that include and, inevitably, are a prosthesis of these print histories and their structuring of conceptions of readership. It thus affirms Spinosa’s contention that there exists “a rich tradition of Canadian writers (particularly women) working to use the digital potential of electronic literature to push the boundaries of the book form and to explore the radical potential of e-lit to engage meaningfully with its readers” (240). And yet Entre Ville also pushes against this faith in its liberatory potential. The poem’s multiple formats - including a “conventional” swath of verse entitled “St. Urbain Street Heat,” a series of film vignettes scattered among the main interface, and its adjoining “A Mile End Bibliographie” and «entre guillemets» sections - weave a CanLit nostalgia that constructs Canadian literature as a more or less unified, or at least holistically understood, entity that packages specifically Canadian experiences in a recognizable literature that is both broadly accessible and fleetingly familiar. Its formats and reference points both function as an invocation of (and entry in) this sprawling print-culture nostalgia and comment on the simultaneous containment and occlusion of this multiplicity that often attends the incorporation of singular, complex literary scenes into print economies as well as the adaptation of the latter to an increasingly digital literary economy. These purposeful limitations are productive as well for their reflection of a parallelism between experiences and representations of Montréal and those of new media, with the former - and its multiple, alternately cross-cutting and mutually exclusive identities - addressing and incorporating the outsider while at the same time underscoring the partial or conditional nature of this inclusion, much as Entre Ville embraces only tentatively the formal possibilities of digital poetics.

To make this argument, I turn to Michael Warner’s notions of publics and counterpublics. Warner’s counterpublics are “defined by their tension with a larger public”; such entities “contravene the rules obtaining in the world at large,” are “structured by alternative dispositions or protocols,” and “make different assumptions about what can be said or what goes without saying” (56). A similar dynamic is present amid the manifold tensions and oppositions that structure both contemporary arts culture as well as a multicultural, multilingual, contested city like Montréal. Sherry Simon, for instance, has described the city as comprised of a French-speaking cultural “matrix” superimposed on centuries in which its “cultural relations were described in terms of elemental spatial and cultural divisions” (3), with a supposedly dual distinction between Anglophones and a Francophone majority being reflected in the city’s class divisions. Far from existing as another cosmopolitan Canadian metropolis, then, Montréal is defined by such structuring oppositions (even if conceptions of the city as bicultural were always somewhat reductive) and their influence on the evolving cultural and linguistic politics of the city’s global phase. On top of this multiplicity exist poetry and poetry communities, which, as Erin Wunker and Travis Mason argue, themselves can be productively understood as constituting a counterpublic - a formation that “articulates alternative ‘publics’” and “makes speaking and thinking critically about those publics possible” (2).

My reading of Carpenter’s engagement with literary Montréal is similarly located. Specifically, I regard Entre Ville as engaging with this kind of counterpublic by invoking - and, ultimately, critiquing by way of participating in - a nebulous cloud of print-culture nostalgia that surrounds Montréal’s position within constructions of Canadian literature and structures new-media engagement with literary production, communities, and markets. Carpenter’s work identifies a tension within the concept of a counterpublic itself, especially insofar as the term is relevant in the world of literature and, particularly, contemporary Canadian poetry. While Warner makes clear that counterpublics need not be “composed of people otherwise dominated as subalterns” (57), he nevertheless defines the entity of the counterpublic itself as “defined by their tension with a larger public” (56) of the sort that, following Jürgen Habermas’s The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere (1989), has been regarded as giving expression to private life and in the process accommodating a male-gendered segment of the bourgeoisie.

Carpenter’s treatment of print-culture nostalgia does not depend on quite this kind of antagonistic relationship with a larger, “official” public; instead, Entre Ville invokes the minutiae of an industry that, although positioning itself as a counterpublic and, in its broadest manifestations, including fringe groups of writers whose work is due to some combination of its politics and formal characteristics regarded as antagonistic to cultural norms, is intertwined with the dominant print culture that creates the conditions enabling the ongoing shift into a digital literary culture. This dynamic fits with Carpenter’s multivalently critical approach to literary culture. In a 2014 interview with Elvia Wilk, for instance, she discusses some limitations of the terminology related to electronic literature, complaining that scholarship on the latter “still orients itself in relation to literary tradition and the book” while she herself tends to focus as well on “landscape, visual art, collage, assemblage, performance, and so on.” Although she complains that readings of her work focus on the literary at the expense of these other fields of inquiry, Carpenter admits that she “do[es] a lot of work in relation to the book”; additionally, in the same interview she questions what she regards as an arbitrary distinction between poetry and prose (stating that this binary exists “mainly due to grant funding and academic categories”) and, crucially, describes the division between creative and critical work as “particularly vexing.”

In the same interview, Carpenter takes issue with “someone” who “once wrote about the aesthetic of bookishness in my web-based project Entre Ville,” referring perhaps to Pressman’s argument that new-media novels, as well as related works such as Carpenter’s, engage with the transformations accompanying digital innovations by providing a “reflection on the book” via “experimentation with the media-specific properties of print illuminated by the light of the digital” (Pressman 466). Carpenter objects that, while the piece indeed includes print references, it more importantly “resulted from a new media art commission by the Conseil Des Arts de Montréal, it was launched at the Musée des Beaux Arts, and was presented entirely within a visual and new media art context.” I would add that Carpenter’s work is also more critical of the complex of print culture erected to deal with the cultural and economic transformations owing to digital culture. While Pressman names Entre Ville as a work that “employ[s] handwritten drawings on notepaper as backdrops for Flash-animated narratives” (467), Carpenter’s critique of this vaguely articulated yet immediately identifiable aura of “bookishness” neither seeks escape from the literary (as her comments in the above interview could be interpreted) nor valorizes print as smoothing our transition into a newly digital world. The formal tensions across the various components of Entre Ville ultimately cohere into a harmonious, recognizable, consumable whole; they anticipate my larger argument that this paradox at the heart of Carpenter’s work allows her to use Montréal’s complex stratifications and intersectional identities, as well as its unique position within conceptions of Canadian literature, to articulate the extent to which new-media poetics remains beholden to the multivalent legacy of print culture and the limiting histories and architectures structuring conceptions of readership. More specifically, Carpenter draws a parallel between the complex, fraught content of Montréal, where multiple fault lines of affiliation call into question the very concept of the insider, and the unknowability of new-media possibilities, which similarly address and incorporate the outsider while at the same time underscoring the provisional nature of this inclusion.

Before even considering the actual words of “St. Urbain Street Heat,” readers may be struck by the poem’s unique scrolling mechanism. The first two-and-a-half stanzas of the poem are visible on the main interface (Fig. 1); to read the rest, a viewer must place the cursor on one of the red arrows located immediately to the right, at which point the column of text slowly scrolls up the “page.” It is in this format that “St. Urbain Street Heat” begins, with brief lines whose consonance and trochaic patterning reflect the “jumbled intimacy of back balconies, back yards and back alleys” Carpenter describes in «this city between us»:

Altars of clutter,

hanging gardens of sound -

the back balconies buckle

under the weight of

high summer

Saint-Urbain Street heat. (1.1-6)This opening passage suggests that the slow-scrolling mechanism may function as an aid for readers to take in the sonic patterning and densely packed meanings of the poem. What is more, the repeating sounds that crowd each line recall the so-called neoformalism that has in recent years characterized much of the city’s Anglophone poetry.6

The poem’s patterning also approximates the combination of physical closeness and cultural distance created by Mile End’s social and architectural characteristics:

In an intimacy

born of proximity

the old Greek lady and I

go about our business.

Foul-mouthed for seventy,

her first-floor curses fill

my second-floor apartment[.] (2.1-7)This section goes on to describe the neighbour fighting with her husband before stating “To each her own” and then making note of the “Undies, / bed sheets and bras” (2.20, 21-22) that form the dividing line between the two pieces of property. Next, they

dance on the line -

a delicate curtain

to separate

her balcony

from mine. (2.24-27)The straightforward rhyme “line/mine” is drawn out visually over several seemingly premature line breaks that themselves keep pace with the slow scroll of the poem. The lineation also draws out this passage’s simple description of a clothes-hanging scene, focusing on the quotidian universals of laundering and the subtle territorializing processes that in any urban environment come along with such tasks. The passage thus recalls a civic and literary history that has been produced by spatial divisions and, in turn, invokes the ongoing effects of those divisions. However, in being preceded by the aphorism “To each her own” and the reference to undies, bed sheets and bras, it also resonates with the innocuous daily choice of undergarments that takes place within the sameness of clothing oneself, thus recalling the omnipresence of the consumer choices structuring such tasks.

Similarly mundane yet complex questions of physicality, consumption, and cultural superstructure are brought out in the third and fourth stanzas, when the sound of birds gives way to “a French man” across the alleyway, who “waits / quietly, until dinnertime, / to aim his trumpet / at our apartment” (3.13-16). The traces of language difference, spatial division, and confrontation structure facts of daily life such as the consumption of food. Difference is spatialized and made audible even as these divisions work ultimately to indicate the common, broadly connective experience of consumption, which is in the following stanza commercialized and presented as an array of purchasable choices, the speaker’s “surrender to / Thailande’s chill interior” (4.5-6) occurring as part of a confident, contented, and digital approximation of formalist print poetry.

The poem’s titular image emerges from this larger framework of commonplace physicality: the hardwood floor is “too hot for bare feet”; footprints are left on “the dust disheveled / dim hallway’s / worn floorboards” (5.3, 6-8). With the references to floors adding a vertical element to the spatial divisions of the previous stanzas, the physicality of heat is here complemented by an additional focus on building materials. Like the laundry, the floorboards are a domestic example of once organic material shaped into usable products - of clothing, wood, and (to jump from the work to its medium and the larger context of print culture) pulp, paper, and pages. Just as Montréal’s urban space is shaped by political and linguistic divisions of the past, the images of organic materials accompanying the poem’s Montréal references and literary influences inherit such identitary divisions and use them in service of literary commemoration.

The poem ends cyclically, with descriptions of dusk and night in “an airless city” (6.5) followed by “a multi-lingual choir of / staccato airs and grievances” (7.14-15) and, in the final stanza, “Another morning” (8.1). Combining its reference to the cosmopolitanism often presented as a new phase of Montréal’s cultural life with another morning of consumption and consumerism, this final stanza casts Montréal’s cosmopolitan present as inextricably linked with the literary documentation (and promotion) of its history of division. Its reference to “Wood smoke from / Fairmount Bagels’ / endless oven” (8.2-4) tightens this connection by employing a now popular, formerly “ethnic” cuisine, as well as its production in a formerly ethnic enclave, as a celebratory reference to “Fairmount Bagels,” an actual bakery in Mile End (although with a nod to the heritage of multilingual signage, too, since the name of the real location lacks the final pluralization). The cycles of consumption structuring life in the city - both literal and literary - persist in the poem’s final image. The words “Another scorcher. / Sesame seeds smile / in the sidewalk’s / cracked teeth” (8.7-10) depict decaying urban infrastructure using images of consumption and facial expression, the “scorcher” some readers would find inconsistent with Montréal’s climate gently subverting cliché without ever going beyond the surface of a daily life built out of expected routines and references.

The formal characteristics of Carpenter’s verse in this section are distinct from the style seen in many of her subsequent works. One of these, Generation[s] (2010), includes text that adheres to a similar poetics. Take, for example, a line from the section “I’ve Died and Gone to Devon”: “A pair of swans swans about near the slipway at Blackness” (52). The pieces “I’ve Died and Gone to Devon” are, like much of the text in Generation[s], built from sentences Carpenter wrote - in the case of this piece, tweets that Carpenter also shared using her Facebook account (154). The pieces as they appear in Generation[s] consist of swaths of such original text that have been subjected to a deselection process, with different permutations of a small number of lines appearing on each page; these sections are sometimes followed by screen shots of the Facebook posts in which Carpenter’s snippets of verse and prose one-liners initially appeared.

What is more, there is a self-reflexivity in Generation[s] that is comparatively absent in Entre Ville. Generation[s] mimics the self-promotional elements of social media (as well as the more traditionally commercial enterprises that would come to draw on this capacity). “Gorge,” a verse piece that is based on a similar deselection algorithm, ends with a prose coda entitled “Lapsus Linguae, May 26, 2010.” It includes the passage, “A gorge is a steep-sided canyon, a passage, a gullet. To gorge is to stuff with food, to devour greedily. GORGE is a new poetry generator by J.R. Carpenter. This never-ending tract spews verse approximations, poetic paroxysms on food, consumption, decadence and desire” (132). This page also quotes Nick Montfort, creator of the story generators Carpenter employs in Generation[s]; Montfort “advises” to “See if you can stomach it, and for how long” - a quotation from a longer testimonial or blurb from Montfort that appears on page 139. “Gorge” is built from a poetics similar to that which appears in “St. Urbain Street Heat,” but in “Gorge” that poetics is used as a repository of source material from which the work itself is extracted using digital techniques. In Entre Ville, however, Carpenter’s playful formalism remains separate from new-media components that function as a frame, with this relatively clear distinction between formats mirroring new media’s partial or incomplete movement beyond the constraints of recognizable print forms and the networks regulating their distribution.

This dynamic is also signalled by the fact that several passages in “St. Urbain Street Heat” refer to the city’s linguistic, cultural, and social diversity even while the consumption occurring throughout the poem is at once universal and a matter of choice that hinges on the arbitrary as opposed to the demographically representational. And indeed, a few elements of Entre Ville contribute to a noticeably leisurely, lyric feel that marks the work as concerned with accessibility but also as registering a literary conservatism. Clicking on the image of the dog situated outside the notepad, for instance, converts the left notebook page into a prose piece called “Sniffing for Stories,” which is unlike “St. Urbain Street Heat” in that it is comprised of paragraphs of justified prose. However, the same scroll mechanism is in operation, this time more accurately aligning with the amount of text to be consumed (or even functioning at a slightly faster pace than that of a casual reader). The piece, which alludes to Carpenter’s description in «this city between us» of the daily routine in which “my dog and I walk through this interior city sniffing for stories,” calculates how many such trips were made over eight-and-a-half years, quantifying their time in Mile End according to various metrics (“Nine thousand three hundred laps of this alleyway works out to around a hundred and thirty thousand minutes”). It ends, however, by referring to their trying “to see things from the dog’s eye view,” concluding, “Chasing stories changing from minute to minute, we never want the alleyway to end.” The countable details of experience are blended with a desire for the infinite; accordingly, this commemoration of the potential of the literary is made comprehensible as well in a bibliography of actual writing that is itself conceivable as countable physical copies to be stocked and sold, rendering the imagery at once celebratory and aware of the print-economy nostalgia that exists in Montréal literature’s extended digital life.

Quite different from these writerly pieces are the short video clips that are linked from clickable spots scattered throughout Entre Ville’s interface. While “St. Urbain Street Heat” condenses reference upon reference into a formal briskness that puts the poem’s content into conversation with the medium, context, and larger public the work invokes, the videos in a sense achieve the opposite. Redolent of multimedia or collage art as opposed to the poetic element of new media, these videos consist of frequently slow-motion depictions of the walls, fences, and plant life found in the alleys of Mile End. While a few combine gif and pop-art aesthetics, the more frequently occurring characteristics locate the pieces in the category of ambient video, a genre scholar and video artist Jim Bizzocchi regards as including both algorithmic invocations of a “screen saver aesthetic” as well as more cinematic pieces marked by visuals that at once “capture a glance at any moment,” provide “details that can sustain a more concentrated gaze,” and incorporate “slow change and metamorphosis” that accommodate still closer consideration (sec. 3-4).

Bizzocchi’s research focuses on the second variant, which he sees as a “video painting,” or a piece whose “archetypal situation” is a “background visual playing on a flat-panel display in the home” (sec. 5). Carpenter’s videos, however, fit neatly in neither category. Although they achieve what Bizzocchi regards as ambient video’s break with the immediacy or foregrounding that characterizes cinema and television (sec. 7), they neither fulfill the simple repetitive function of a screen saver nor provide the cinematic variant’s length or nuanced engagement with attention span. Instead, each lasts an average of ninety seconds (the shortest runs at thirty-seven seconds, the longest two minutes and thirty-three seconds); the sameness that is dispersed among several vignettes achieves the reverse of the longer pieces Bizzocchi describes, not capturing a range of attention spans as much as showcasing an absence of visual stimulus. What is more, the brief “journeys” through Mile End they depict are lodged in the flat aesthetic of the hand-drawn “notepad” map; the limited movement of the frame seems to recreate a literal scratch just beneath the surface, into an ostensibly three-dimensional world of Mile End that replicates the decidedly two-dimensional format of the main interface. Additionally, the videos, in being hidden in plain sight across the interface, exist within a field of interactivity but are themselves dead ends - the mystery of their location is easily “solvable,” but this solution leads only to the understated ambiance of the clips. Indeed, it is difficult to imagine that many viewers of Entre Ville would choose to sit through all of them; a few viewings confirm the uniformity of the series. In this respect, Carpenter’s videos do not produce “layered and convoluted imagery and subtly embedded secondary visual artifacts” (Bizzocchi sec. 4) as much as direct a viewer’s attention back toward Entre Ville’s conventionally literary elements, in the process de-emphasizing the work’s multimedia aspects.

The peculiar emptiness of these video pieces also contrasts with the lyrical abundance of “St. Urbain Street Heat.” Rather than providing a sense of constrained movement through a dense column of signifiers, the clips’ consistent sampling of the genre of ambient video registers a spreading-thin of the minimalism that defines and unites these pieces. This free-floating emptiness is juxtaposed with the content-heavy, locally situated, reverent multivocality of “Mile End Bibliographie” (and, as will be discussed shortly, «entre guillemets»); the result invokes Daniel Morris’s in-betweenness, but with an added reference point of deracinated, cosmopolitan, globally dispersed - and therefore uniform - art-world ambience, which, despite being located in the Mile End alleys themselves, is at odds with the Internet-age curation of bibliographic data that evinces at once the vitality of the local and a detached critique of the latter’s inscription as nostalgia. Then again, the videos are neither entirely removed from the poem’s subject matter nor putting their juxtaposition in service of critique - one of the video pieces features the words “Across the alleyway a French man waits, quietly, until dinnertime, to aim his trumpet at our house” (see Fig. 2). The passage, part of “St. Urbain Street Heat,” is rendered in handwriting on notepaper next to the video apparatus, but here the text is reproduced as prose rather than lineated as in the poem itself. Such references to itself aid in Entre Ville’s presentation of Montréal literature as a readily consumable whole as much as a complex formation that is specially suited to new-media excavation.

This dynamic is most evident in “Mile End Bibliographie” and «entre guillemets». These pieces offer an accessible introduction to Montréal literature that stays close to the city’s writerly touchstones. Listing works by Nicole Brossard, Anne Carson, Leonard Cohen, David Fennario, Irving Layton, Heather O’Neill, Mordecai Richler, Michel Tremblay, and Shulamis Yelin, the brief bibliography is even somewhat Anglocentric - resonating once again with the trace of Montréal formalism permeating “St. Urbain Street Heat.” The novels of O’Neill and Richler, meanwhile, are widely accessible works that have won awards and are even assigned in high-school English classes. It is difficult to imagine examples of “local” literature, at least in a Canadian context, that could be considered more mainstream.

«entre guillemets», meanwhile, lends an interactive facet to the bibliography that undergirds Entre Ville. It too, however, draws from an Anglo-centric reading list consisting of the works in “Mile End Bibliographie” along with other, non-Canadian titles, including those Carpenter cites as inspirations in «this city between us». And the mechanism by which it generates quotations - a passage from Carson will, when a reader selects the “CLICK TO RENEW” option, be followed by one from Cohen - repeats itself so frequently as to come across as a still more minimal repository than the bibliography. Indeed, given that various quotations from each text come up, one could reasonably expect the variety of passages from which it selects to be noticeably larger than that of the bibliographical entries. The literary complexity of the city, as documented in «this city between us» and by numerous other writers and scholars, is here purposefully limited and representative of the speaker-curator’s subjective preferences as opposed to indicative of any deep excavation of the topic.

It is notable, then, that these two sections invoke (to a greater degree than do the clicking and scrolling mechanisms structuring Entre Ville’s textual and video-based components) Hayles’s conception of technotexts. Hayles identifies as a technotext any work that interrogates the “inscription technology that produces it,” thus mobilizing “reflexive loops between its imaginative world and the material apparatus embodying that creation as a physical presence” (25). She adds that, while not all works of literature do so explicitly, we must keep in mind that form always affects the content inhering in its words and extra-verbal components. Technotexts take this omnipresent symbiosis into the expanded field of new media; they “strengthen, foreground, and thematize the connections between themselves as material artifacts and the imaginative realm of semiotic signifiers they instantiate open a window on the larger connections that unite literature as a verbal art to its material forms” (25-26).

Entre Ville exhibits a similar self-reflexivity. By the time one encounters the work’s slim library of Montréal sources, however, the diversity of its new-media components is at odds with the conventionality of its textual sections and the mainstream appeal of its frame of reference. «entre guillemets» is relevant in that it not only gives “samples” of Montréal’s literary culture, but that these samples do not pull from various levels of the uniquely cross-cutting linguistic, cultural, and spatial politics of the city. Instead of registering a complex cosmopolitanism sitting atop decades of spatialized cultural, linguistic, and class divisions, the repository of “Mile End Bibliographie” and «entre guillemets» plays it safe - other than (arguably) Brossard, Carson, and the code-switching Fennario, Montréal’s heritage of radically experimental literature is absent. What emerges from these two sections is instead a well-known, largely Anglophone literary portrait of Montréal that would not seem out of place if spread across a couple weeks devoted to the city as part of a CanLit survey course.

Much of Entre Ville’s text reflects this commitment to evoking an accessible and broadly appealing conception of print literature. “St. Urbain Street Heat” registers the city’s status as the poetic home of Anglo-formalist figurehead Carmine Starnino, whose influences include long-term Montréal residents Eric Ormsby and David Solway. Some such writers - such as Michael Harris and Daryl Hine - bring to mind a similarly restricted internationalism, with Harris having been born in Scotland and Hine, who attended McGill University before leaving Canada, having gone on to become editor of Poetry. (Hine has stated that he left Montréal due to a lack of opportunity; Jason Guriel, referring to the fact that Hine attained only a position in a bookstore, has written, “I wince at the uniquely Canadian foresight that offered a future editor of Poetry no more than a retail job.”) The broadly formalist aesthetics of such writers gives the impression of a Montréal that is the seat of a limited poetic worldliness; this kind of formation even recalls A.J.M. Smith’s now seventy-five-year-old declaration of the Canadian poet’s cosmopolitanism, which Smith defined against a narrow-minded nationalism. Smith’s argument is made in predictably dated terms; his conception of the cosmopolitan Canadian poet as one who was unafraid of drawing on either European or American influences in the process of “importing something very much needed in their homeland” (31) was, before even the end of the 1940s, decried by writers such as Louis Dudek and Raymond Souster as repeating European colonialism (Gorjup 8).

In spite of Carpenter’s intricate new-media format, then, a stroll through the contextually loaded lines of “St. Urbain Street Heat” is also a tour through the city’s stately, emphatically Anglophone literary heritage - one that may gesture toward the various exclusions and unknowable aspects of the city but which is itself nevertheless an accessible registering of this complexity. Although not frequently regarded (particularly among avant-garde circles) as a particularly exciting chapter of Montréal literary history, this formation plays a major role in Entre Ville, structuring the bulk of the work’s text even if “Mile End Bibliographie” and «entre guillemets» do not devote much space to it. This kind of formal conservatism is a local characteristic, certainly, and it may also simply reflect a substrate of preferences one would expect to find in any inescapably subjective curation of a literary formation or scene. But it is also relevant here because, in being integrated with the bulk of the work’s seemingly conventional text (as opposed to included in the bibliographical sections), it highlights the easy-reading qualities of several parts of the work’s subtle commentary on print culture, consumption, and new media.

So while Entre Ville functions as a technotext, it also signifies on the level of a reputational, intangible “scene” that, in being perfectly suited to processes of curation that enhance its accessibility or marketability, nevertheless critiques and contributes to this formation. Its very treatment of Montréal’s literary diversity is conservative on the level of bibliography, language, and form. Despite its obvious incorporation of the city’s Francophone identity and literary matrix, as well as, to a lesser extent, its Jewish history, the work’s various components allude again and again to Anglophone modernism and neoformalist poetry. Due especially to its appearance alongside these elements, the repository invoked by «entre guillemets» transcends traces of the two solitudes not by illustrating or enabling meaningful exchange, but rather by enveloping the entire structure - literary cliché as well as a history of division and its lingering effects - in the accessibility of its new-media curatorial venture.7

A useful point of comparison for Carpenter’s curatorial project is Simon’s Translating Montréal, an examination of the city’s evolution from a supposedly dual to a more cosmopolitan cultural situation as part of which Simon unpacks the trope of the cross-town journey from English-speaking Westmount to the working-class Francophone neighbourhoods on the opposite side of Saint Laurent Boulevard (with a literary version of this expedition having apparently been pioneered by modernist Anglo-Montréaler F.R. Scott [31]). Rather than recreate this journey, Simon seeks to “illuminate the history of passages” among languages, cultures, and literatures, showing “how they signal changes in direction or intensity of exchange” in relationships “proximate difference” (7). In a sense, Carpenter offers a similar cross-section as opposed to the subject-centered “voyage” or “exchange” experience common to Montréal literature as well as to Simon’s exploration of it. And, indeed, Simon’s examination of Montréal’s “dispersion of people and languages across the time-honored boundaries” and the resulting “city of after-images, of words effaced and superimposed” interrogates precisely that duality in which deep historical divisions are transcended but that very transcendence inevitably recalls or reproduces those divisions. Her explication of the reappropriation characterizing the city’s recent cultural and spatial politics - the many ways “words and names take on new resonance” and this “new language renames, scratches out, translates ‘over,’ reducing the words of the past to weak echoes” that nevertheless “hover over the murmurs of the past” (11) - could just as easily be referring to the simultaneous reverence for print culture and transcendence of it that is, via the quotation-display feature, evident in “Mile End Bibliographie” and «entre guillemets».

And yet Carpenter’s cross-section of the city does not seek to penetrate too far beneath the surface. Translating Montréal refers to the city’s history of documenting its writerly mythologies, a phenomenon that predates many of the city’s literary giants and includes Malcolm Reid’s The Shouting Signpainters (1972), which describes the young Francophone writers who contributed to the journal parti pris (1963-68). Entre Ville, however, is not concerned with such historical excavation. It acknowledges Montréal’s status as uniquely storied but also self-documented - not in a self-mythologizing way but rather in the sense that each solitude has reported on the literary life and activities of the other, both to share this information with its in-group and for the experiential value of attaining proximity to the opposing “side” that is the destination of the cross-town journey. Entre Ville documents and participates in - and by doing so critiques - the culmination of this process and sublimation of these trends into the print-culture mythologies that are both a seemingly unavoidable reference point for new-media poetics and a factor that will influence the development of the latter.

Carpenter’s invocation of the not-quite-countercultural counterpublic that is the Montréal quarter of Canadian literature was in some way visible to me the first time I came across Entre Ville. At the Digital Humanities Summer Institute at the University of Victoria in 2015, I attended an introductory course in electronic literature, one of the workshops of which involved discussions of Entre Ville. This experience indicated that the limited multiplicity of the piece accommodated a range of knowledges and experiences. Participants who were not so familiar with Montréal or its literatures struggled with what they regarded as the arbitrariness of the selection (regarding Cohen as primarily a singer-songwriter, for instance, who was appearing alongside at least one French-language writer with whom they were not familiar). Meanwhile, those with knowledge of the city’s literary history, in itself or as part of general familiarity with Canadian literature, could read the list either as full of important, influential reference points or, depending on their level of study and areas of expertise, regard it as overly popular and predictable - that is to say, something of a failure, at least if considered in the context of the literary anthology or digital repository.

But so too does this dynamic sustain nostalgia for Montréal literature (and a print economy generally) in both print and post-print apparatuses. Entre Ville alludes to the expected or the clichéd, just as it inescapably refers to print and foregrounds the limitations of its interactivity. It captures a metapopularity that at once accommodates, identifies, and parodies different levels of knowledge, in the process enveloping its own new-media configuration as well as its seemingly earnest lyrical engagements and subjective choice of literary reference points; it sprawls in its literary-visual expanded field, but it does so invitingly, cautiously showing us that the very possibility inherent in its format is built not only on print culture, but also on the dispersed cultural industries and CanLit surveys that ultimately produce knowledge of the city and its literary richness as well as the consumer culture of bookishness that unproblematically extols that culture. The familiarity of the section almost makes it resemble the short, screen-width lists of recommendations that follow an Amazon purchase, with Mile End’s many gods coded as gently welcoming more than radically local or unknowable.

In a sense, then, Entre Ville converts the vast source material of Montréal’s languages, literatures, and identities into a curiously consistent ritual honoring the familiar gods of Mile End. In smoothing over the contestations, divisions, and multiplicities of the city and its writing, Carpenter’s engagement with an ostensible literary counterpublic signals the potential containment of new-media poetics’ expanded field - in barriers to access, in the hierarchies and power structures of the academy and gallery, and in the very relations of literary production, circulation, and consumption upon which any radical writing may depend. Seen in this light, the multiple points at which Entre Ville gives its viewer a chance to contact Carpenter take on more than merely practical significance. Such a rare opportunity for direct communication between readers and an author itself asks, by virtue of being open to receiving answers, who, precisely, is the readership that desires to transcend the medium and related conditions that have hitherto determined readership itself.

Works Cited

Bayard, Caroline. The New Poetics in Canada and Quebec: From Concretism to Post- Modernism. U of Toronto P, 1989.

Bizzocchi, Jim. “The Aesthetics of the Ambient Video Experience.” The Fibreculture Journal, no. 11, 2008, http://eleven.fibreculturejournal.org/fcj-068-the-aesthetics-of-the- ambient-video-experience/.

Carpenter, J.R. “Elvia Wilk in Conversation with J.R. Carpenter.” Interview by Elvia Wilk. Lemon Hound, March 14, 2014, https://lemonhound.com/2014/03/14/elvia-wilk-in- conversation-with-jr-carpenter/.

---. Entre Ville. Lucky Soap, 2006. http://luckysoap.com/entreville/index.html/.

---. Generation[s]. Traumawien, 2010.

---. “Two Poems and a Conversation with J.R. Carpenter.” Interview by Sina Queyras. Lemon Hound, November 11, 2010, http://lemonhound.com/2010/11/11/two-poems-and-a- conversation-with-j-r-carpenter/.

Gibson, William. Neuromancer. Ace, 1984.

Gorjup, Branko. “Incorporating Legacies: Decolonizing the Garrison.” Northrop Frye’s Canadian Literary Criticism and Its Influence, edited by Gorjup, U of Toronto P, 2009, pp. 3-28.

Guriel, Jason. “The World Stands Still and Still We Flow.” Review of Recollected Poems: 1951-2004, by Daryl Hine. Poetry, Poetry Foundation, January 3, 2008. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/articles/68995/the-world-stands-still- and-still-we-flow.

Habermas, Jürgen. 1989. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. Translated by Thomas Burger, The MIT P, 1989.

Hayles, N. Katherine. Writing Machines. MIT P, 2002.

Morris, Adalaide. “New Media Poetics: As We May Think/How to Write.” New Media Poetics: Contexts, Technotexts, and Theories, edited by Morris and Thomas Swiss, MIT P, 2006, pp. 1-46.

Morris, Daniel. Not Born Digital: Poetics, Print Literacy, New Media. Bloomsbury, 2016.

Nichol, bp. First Screening. Edited by Jim Andrews et al., vispo.com, 2007, http://vispo.com/bp/introduction.htm.

Pressman, Jessica. “The Aesthetic of Bookishness in Twenty-First-Century Literature.” Michigan Quarterly Review, vol. 48, no. 4, 2009, pp. 465-72.

---. Digital Modernism: Making It New in New Media. Oxford UP, 2014.

Punday, Daniel. Writing at the Limit: The Novel in the New Media Ecology. U of Nebraska P, 2012.

Reid, Malcolm. The Shouting Signpainters: A Literary and Political Account of Quebec Revolutionary Nationalism. McClelland and Stewart, 1972.

Rettberg, Scott. Electronic Literature. EPUB ed., Polity P, 2019.

Simon, Sherry. Translating Montréal: Episodes in the Life of a Divided City. McGill-Queen’s UP, 2006.

Smith, A.J.M. Introduction. The Book of Canadian Poetry: A Critical and Historical Anthology, edited by Smith, W.J. Gage, 1943, pp. 3-31.

Spinosa, Dani. “Toward a Theory of Canadian Digital Poetics.” Studies in Canadian Literature, vol. 42, no. 2, 2018, pp. 237-255.

Starnino, Carmine. Introduction. The New Canon: An Anthology of Canadian Poetry, Signal Editions, 2005, pp. 15-36.

Waber, Dan. “On First Screening.” First Screening, by bpNichol, edited by Jim Andrews et al., vispo.com, 2007. http://vispo.com/bp/introduction.htm.

Warner, Michael. Publics and Counterpublics. Zone Books, 2005.

Wunker, Erin, and Travis Mason. Introduction. “Public Poetics.” Public Poetics: Critical Issues in Canadian Poetry and Poetics, edited by Bart Vautour et al., Wilfrid Laurier UP, 2015, pp. 1-23.

Footnotes

-

There are exceptions - Jim Andrews and Lionel Kearns have produced digital poetry. Andrews, however, is far from a recognizable name in the print universe of CanLit, while Kearns is known more for his print experiments. That both writers appear as architects of the 2007 online rehabilitation of First Screening speaks to the separateness and sparseness of this endnote-dwelling section of the Canadian poetry universe. ↩

-

As Dan Waber puts it, Nichol’s interest in digital poetics can be explained by “deductive reasoning”: “could/did he have access to computers? If yes, then there is a high probability that he made poems with computers.” ↩

-

As outlined in «this city between us», Entre Ville was commissioned in 2006 by Montréal’s OBORO and appeared shortly thereafter at the Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal; it can be accessed on Carpenter’s website, with additional material dated 2007, and has also been converted into a mini-book. ↩

-

The main text of Writing Machines (2002) is rendered to invoke a computer screen, and it further gestures to this medium by sporadically appearing distorted in the same manner as would the display of a contemporary PC whose screen settings were being adjusted. ↩

-

This biographical information is drawn from «this city between us» and Carpenter’s 2010 interview with Sina Queyras for Lemon Hound. ↩

-

Carmine Starnino himself wryly refers to this term’s prefix as conveying “the drasticness of [its adherents’] suspected conservatism” (27); I use the term here not to invoke this kind of judgment but rather as shorthand for the type of verse characterized by an abundance of traditional formal devices. ↩

-

One productive area of French-English literary exchange was feminist and experimental writing, including especially concrete poetry - Caroline Bayard’s The New Poetics in Canada and Quebec: From Concretism to Post-Modernism (1989) documents the key moment when “Canadians and the Quebecois finally acceded to the international concrete movement” (34). The bibliographical sections of Entre Ville, however, omits this key area of formal and media-based experimentation. ↩

Cite this article

Watts, Carl. "“the many gods of Mile End”: CanLit Print-Culture Nostalgia and J.R. Carpenter’s Entre Ville" Electronic Book Review, 7 February 2021, https://doi.org/10.7273/bb5c-8919