The Praxis of the Procedural Model in Digital Literature, Part 1: Structural Aspects of the Model

Phillipe Bootz defines and situates a set of artifacts, devices, material components and human groups that are in contact with earlier procedural "dispositifs." The procedural model, in Bootz's 30 year long research, analyses, theoretical frameworks and observations, expressly distinguishes human beings from material components. In opposition to artificial/human proposals such as the trans-human or the cyborg. The dispositif, in Bootz's presentation, only concerns the physical world. It does not contain signs, is not concerned with literature or art. And neither are individuals, within the procedural model, considered for themselves. They are actors at a given moment. Their positions are characterized by their power to directly act on the artifacts and objects of the dispositif.

1. Introduction⏴Marginnote gloss1⏴From the year 1999: Philippe Bootz celebrates the 10-year anniversary of alire, an innovative digital journal. Translation by James Stevens.

— Daniel Johannes Rosnes (Dec 2024) ↩

The Procedural Model has become a general theory of communication (Bootz, 2016), but it was first intended to describe and deal with digital literature (aka, e-lit). I began to think about it in 1994, and in (Bootz, 1996) I published my first paper on it, after having observed for 7 years the behavior of the works published in alire. The project has been greatly developed since this date.

The Procedural Model has three purposes concerning e-lit:

- Compare different theories of digital literature inside the same framework.

- Analyze and evaluate works.

- Express proposals about important topics in e-lit regarding for instance: – The nature of the work – Preservation issues – Reading contexts

It is reasonable to assume that there are several forms of digital literature in circulation. The numerous typologies built into the e-lit field testify to this. I have mainly set out to reflect on these questions about programmed digital literature; which is to say, literary writing in which the author (or group of authors) creates the program of the work.

In this essay, I will first expound the procedural model theory, then indicate how we can compare different theories in it and show some semiotic analyses using the model. I will finish with a general overview covering about 30 years of research, analyses, theoretical frameworks and observations. I will not go into all details and not all analyses will be addressed in the essay. In particular, I will not analyze specific textes-à-voir.

2. A model in four complementary dimensions

The model is organized according to four complementary but hierarchical dimensions: material and physical, communicational, semiotic and “mind context” in a broad sense, with this last dimension covering everything in the mind of an actor that contextualizes interpretation.

At the end of this essay, a glossary resumes the definitions of all specific terms introduced in this chapter.

2.1 Materiality in the procedural model

2.1.1 The dispositif

a) Definition

The “dispositif” is the main concept in the procedural model. This dispositif consists of all the artifacts, devices, material components and human groups that are in contact with these material components: authors, readers, researchers, curators… The procedural model expressly distinguishes human beings from material components, in opposition to artificial/human fusion proposals such as the trans-human or the cyborg. We can note that the dispositif only concerns the physical world; it does not contain signs, it is not concerned with literature or art

Within the procedural model, individuals are not considered for themselves but for their role as actors at a given moment. The model identifies these roles as positions in the dispositif. Positions are characterized by their power to directly act on the artifacts and objects of the dispositif. This power is limited and relates only to a part of the dispositif.

The same individual can therefore occupy different positions but never simultaneously. It is why the model makes a difference between a reader who is a person and a Reader that is a position in the dispositif. It is the same difference between author and Author.

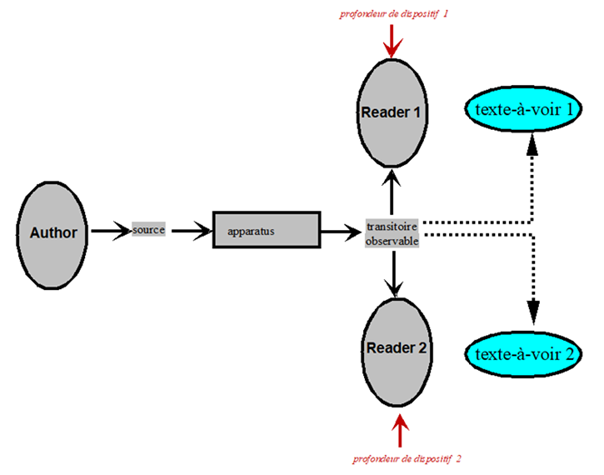

The model describes this dispositif according to a structural schema.

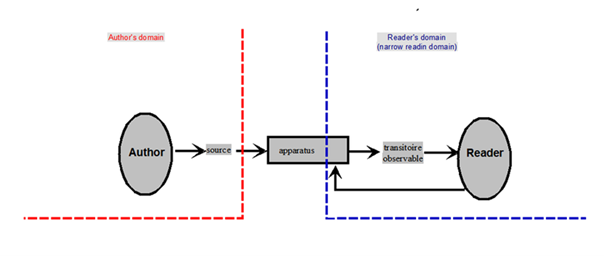

b) The main axis

The procedural model stipulates that a physical transformation organizes the dispositif. In programmed digital literature, it is mainly the computing transformation from a source program written by the Author into an executable file running for the Reader.

The Structured analysis and design technique (SADT) methodology of engineering (Favier & all, 1996) stipulates that such a transformation takes place within a black box. In digital literature, this black box is made up of the various computers, screens and digital devices involved in the dispositif, including the Internet if necessary. Other material elements can be added, such as objects, for example during a performance, or a specific space and environment, for example in an installation. This black box is named the apparatus in the procedural model.

The transformation is fed by a work material at the input of the apparatus and produces another work material at the output. The model names respectively source and transitoire observable, elements that are found in these materials. These terms have been kept in French to avoid confusions done by multiple translations. They should not be translated.

Source and transitoire observable are physical components, not texts, nor sets of signs. We must consider that the source and the transitoire observable are different material events, even when the transformation in the apparatus can be reduced to a simple transmission. At least, they do not exist in the same space. Author and Reader in the schema are positions in the dispositif an individual can occupy.

In the typical situation of a literary production programmed by an author in the Author position and read by a reader in the Reader position on their computer, the computers used by the author and the reader constitute the apparatus. The set of binary files constituting the materiality of the source program created by the author is the source, and the transitoire observable is the luminous phenomenon that appears on the screen of the reader’s computer. This phenomenon is observable and it is transitory, it disappears at the end of running. This schema also occurs in more simple situations. For instance, when an individual writes a tweet on their mobile, they are an Author, the tweet is the source when it is sent and another reader reads it as a transitoire observable on their own phone in a Reader position.

The Author position creates the source and the Reader position deals with the transitoire observable. The transformation inside the apparatus is, for instance, constituted by the transformation of the source into an app and the diffusion of this app on the Web. The devices the Author position uses to create the source is a part of the Author position itself because the transformation inside the apparatus begins when the source is finished. The Author position is then a sub-system inside the dispositif. As soon as the source is finished and enters the apparatus, the Author position can no longer control what happens. The Reader position can act on a limited part of the apparatus only: it can use a mouse or a keyboard but it cannot act on many steps of the transformation, for example the compilation process; it cannot change the executable file or the published files on the server.

The power to act from the positions of Author and Reader is then limited to a specific domain in the dispositif. It is what I call the Reader’s and Author’s domains. Notably, the Reader cannot access the source that is an important part of the dispositif and a material component of the work. Therefore, reception of the work is limited and incomplete in this position. It is why I qualify this reading as “narrow reading” and the Reader’s domain can also be named the narrow reading domain. The Reader position has no access to the whole material of the work; they do not reach the source. But neither does the Author position access the whole of the materials of the work. Which is to say, they do not access the transitoire observable.

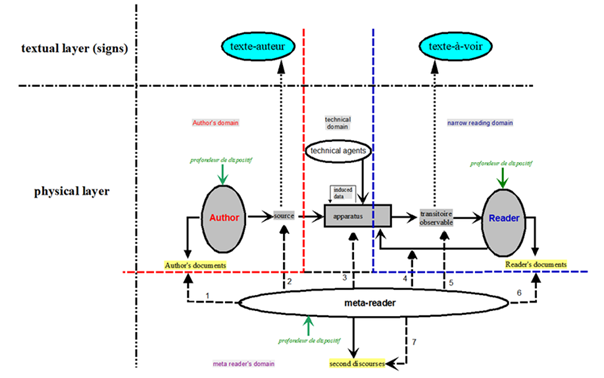

c) The complete structural schema

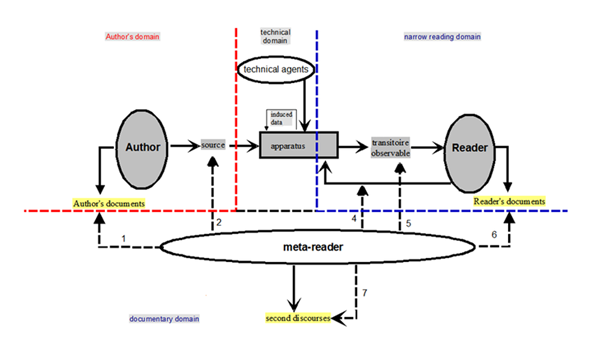

The main axis only takes into account the structuring transformation from the source into the transitoire observable, but other features of the dispositif are not directly concerned with this transformation.

First, some entities managed by human beings govern the behavior of the apparatus. In digital literature they are enterprises like Apple, Microsoft, and IBM, that have created the software, Operating System, hardware, and devices of the apparatus. They influence the running program of the work. They constitute the position of technical agents. Technical agents have the true power on the apparatus and can shape the transitoire observable in a way that is not governed by the intention of the Author. The Author position is subordinated to the technical agents’ power. In a digital apparatus, the lability phenomenon shows this subordination in its dependency on the transitoire observable to the technical context of running (the hardware, the OS, the installed software, the Brower, the bandwidth, etc. all elements that play a role while the work’s program runs) and not only to the source. When the program of the work runs in different technical contexts, it creates transitoires observables that seem different, even if this program is not generative nor hypertextual. These differences do not come from the program but from the influence of the technical context on the running process itself. The transitoire observable then is labile. The procedural model calls lability this dependency of the transitoire observable up on the context of running. I will come back to this issue.

Inside the apparatus, the running program of the work and technical agents can create data that are not present in the source and that appear neither to the Author position nor to the Reader, but that influence running and impact the transitoire observable. They are induced data. For example, cookies, parameters of an AI created by deep learning, or internal induced data created by the Reader activity. In some cases, technical agents can access some of these induced data. Unlike lability, induced data does not always exist in the apparatus.

Meta-reading is another main position the procedural model introduces, perhaps the most significant. It is a transversal access to the apparatus, that means that a meta-reader does not directly act on the apparatus as a reader does in a Reader position. It is the position in which all observers find themselves, like researchers or critics. For instance, the first time a researcher accesses and discovers a digital work, they are a Reader engaged in narrow reading. But when, later, they analyzes the work, they are no longer in a Reader position but in a meta-reader one because they observe some parts of the dispositif to answer specific questions they ask it, to obtain information. This analysis, often, is instrumented in contrast to narrow reading. For example, the researcher records the transitoire observable in video to analyze it more simply and without cognitive overloading.

Meta-reading can also be a situation of reception, different from the Reader position. I will come back to this issue.

Meta–reading is very diverse and heterogeneous. The structural schema shows 7 modalities of meta-reading, but others are possible, depending on what part of the dispositif our meta-reading focuses.

Each position can create information outside the apparatus. They are documents. They are interviews of authors, comments by readers, papers by researchers or journalists and so on.

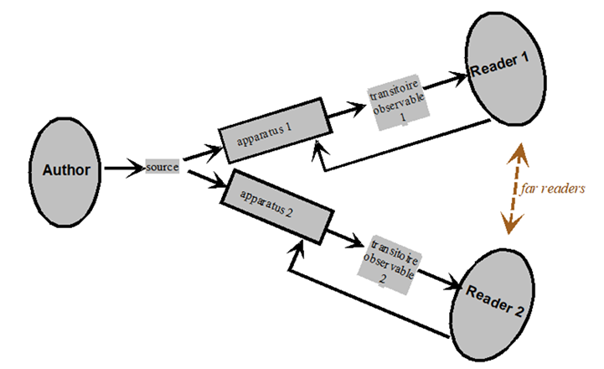

2.1.2 Lability and far readers

Many observations show that the transitoire observable not only depends on the source but also on the technical context of running (Bootz, 1999, 2004). It is the lability phenomenon; it demonstrates the power of a technical agent’s position, the ability to undergo change.

I consider lability to be the main property of digital dispositifs. It forces us to rethink our understanding of digital literature, independently of any generative, interactive or animated properties.

Lability, partially or in totality, destroys the causal relationship between the source and the transitoire observable. This claim is not intuitive because the main axiom in computer science is that the program the programmer programs totally describes the product shown while running. This axiom is in fact only partially true. If it were totally true, old programs would run on current computers and works programmed in Flash would also continue to run today. Lability occurs because of technical, legal, or marketing impact on the apparatus. Lability is omni-present. It cannot be avoided, and it is reproducible on a given apparatus. It is generally impossible to detect lability because it has nothing to do with noise.

Because of lability, two different readers reading on different apparatuses will observe different transitoire observables: a difference that is not inscribed in the source program. These readers are called far readers because they do not observe the same transitoire observable as the current Reader. When you read a digital work in a Reader position, other readers who read, will read or have read the same work in other contexts (different computers for instance) are your far readers. If considering that the transitoire observable holds the work, far readers do not access the same work. We will see later how the procedural model deals with this paradox.

The difference lability creates is not intentional. It involves the author reconsidering their creative goal because they cannot really manage or fully imagine what the reader looks at. What does it mean to create a super complex text animation if the esthetic is modified on the reader’s screen?

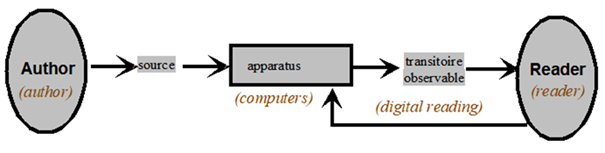

2.1.3 Narrow reading vs meta-reading

In the procedural model, the Reader position domain does not stretch out to the source but this can be accessed via meta-reading. It is why the reading activity in the Reader position is called a “narrow reading”: in this position, the reader has no information about the source and, often in digital reading, causes some trouble and incomplete reading. We observe this non-fulfilment in text generation and hypertext, but it can also occur in text animation. It is really a frustrating situation of reading I have observed since alire appeared as far back as 1989. A typical French aesthetic is based on this incomplete reading, namely the aesthetic of frustration.

But narrow reading is typically what a reader does when they read a piece on their computer or mobile without knowing anything about the program. It is the most common situation of reception. In narrow reading, the reader directly follows the running program of the work and acts on the apparatus, without using another tool such as a recorder.

In some kinds of literary events, for instance performances or installations, the person reading is in another situation. They are in fact a meta-reader and not a Reader in narrow reading. That’s why it is useful to specify the nature of the situation. Some situations are in public reading (performances, installations) and others, private. Both situations lead to a different structural schema, a unique enactment of the dispositif. Public and private readings do not generally refer to the nature of the work but to the situation of running, an operative more than conceptual literacy. In private reading, the author cannot manage the effect of lability. In public reading they can because they are a member of the technical agent’s position for running. It is the only case when the author can manage lability.

[gallery size=“full” columns=“2” ids=“11600,11601”]

2.2 Communication in the procedural model

The procedural model does not understand communication as a transmission from the Author to the Reader positions. For instance, in a performance, the communication occurs from a technical agent, the performer, to a meta-reader, the audience.

I claim that the dispositif describes a situation of communication as soon as at least one human being in some position gives meaning to some part of the dispositif and that they attribute this meaning to the behavior in the dispositif of another human being staying in another position, away from the keyboard or screen they have in hand, and separate from programs that are visible, and programmable.

It clearly appears that in this case an individual cannot communicate with themselves.

2.3 Semiotic dimension in the procedural model

2.3.1 Texte-auteur and texte-à-voir

The model takes into account the fact that different individuals can build different texts on the same physical reality because they perceive this reality differently and do not put the same semantic weight on what they perceive. It is why the model explicitly enacts a difference between the physical elements an actor can perceive in the dispositif and the set of signs, the text, they will really perceive according to their semiotic decision.

The set of signs an actor perceives on the transitoire observable is called the texte-à-voir of this actor. The set of signs an actor perceives on the display or on the listing of the source is called the texte-auteur of this actor.

Texte-à-voir and texte-auteur are composed with signs and media, whereas there are no signs and no media in the source and in the transitoire observable.

A device like a camera or a microphone can record the source and the transitoire observable because they belong to the real world, but no captor can record the texte-à-voir or the texte-auteur.

Texte-à-voir and texte-auteur are not the meanings of the transitoire observable and the source but their signifiers. They will both be interpreted in a classic way. The distinction between materiality and text does not affect the possibility of multiple interpretations of this text.

Using Klinkenberg’s model of sign (1996), we can say that the transitoire observable is the stimulus of the texte-à-voir and the listing of the source, the stimulus of the texte-auteur. Texte-à-voir and texte-auteur have both a signified and a referent.

[gallery size=“full” ids=“11603,11604,11605”]

Note that the binary files forming the source cannot generally be directly perceived by an actor and then cannot be the stimulus of a sign.

2.3.2 Profondeur de dispositif

The physical context that plays a role on perception and then on interpretation, like distance, sound volume, and light, is a part of the apparatus.

But all nonphysical features that explain the semiotic decision can be condensed in one concept: the profondeur de dispositif1. This term is best placed in relation with affective, mind and cognitive contexts. It contains the psychological state of the actor, their culture, belief, knowledge, understanding and imaginary depth: what is their apparatus, what are the roles of other actors, their own role in depicting the dispositif and so on.

Each individual has their own profondeur de dispositif that is different from those observed and experienced by others. It means that two different individuals seeing the same transitoire observable can perceive different textes-à-voir on it. Ditto for the source and the texte-auteur.

The profondeur de dispositif for a position gathering several individuals also exists. It results from a negotiation or a power structure inside the position.

The profondeur de dispositif explains behaviors and meaning creation by the position. It makes a semiotic decision possible but also it constrains this decision and forbids other possible interpretations.

The procedural model does not consider that correct or false interpretation could happen, but, regarding one perception and interpretation, it tries to find the properties of the profondeur de dispositif that leads to that specific interpretation. I often did this exercise with my students: after screening a work, I would ask them individually what they had seen, read, and understood. Several classes of interpretations and perceptions emerged. Then we worked together to detect which elements in each class they hadn’t perceived, and which they had considered more important. We then examined what this revealed, for example, a more visual than textual culture, or a very classical conception of textuality that makes understanding visual poetry impossible… Sometimes they mentioned elements foreign to the work, such as their own language or cultural preconceptions.

Taking into account the profondeur de dispositif, means that meaning and knowledge about the dispositif always are relative and never absolute because the researcher themself is a meta-reader with their own profondeur de dispositif. Two individuals having close profondeurs de dispositif would perhaps detect similar textes-à-voir in the same transitoire observable and the same can be said for the texte-auteur.

Because of the profondeur de dispositif, all understanding and knowledge about the dispositif is partial, relative to a point of view. The procedural model itself is a point of view because it is designed as a second discourse based on my own meta-reading analysis.

2.3.3 The complete schema of the procedural model

We can summarize all of this information in a single schema that is the basis for the procedural model.

In the following schemata, I will distinguish with colors the different positions: black for the technical agents domain, red for the Author position domain and blue for the Reader position domain.

Bibliography

Bootz, Philippe. «Un modèle fonctionnel des textes procéduraux». Les Cahiers du CIRCAV, no. 8 (1996): 191-216.

Bootz, Philippe. «Ai-je lu ce texte ?» In Littérature, informatique, lecture. De la lecture assistée par ordinateur à la lecture interactive. Limoges: Limoges University Press(PULIM), 1999 : 245-274.

Bootz, Philippe. «der/die leser ; reader/readers». In P0es1s. Asthetik digitaler Poesie, The Aesthetics of Digital Poetry, édité par Friedrich W. Block, Christiane Heibach, et Karin Wentz, 93-121. Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2004.

Bootz, Philippe. «Une approche modélisée de la communication ; application à la communication par des productions numériques”». HDR, Paris 8, 2016. https://archivesic.ccsd.cnrs.fr/tel-02182750.

Favier, Josette, Serge Gau, Dominique Gavet, Ignace Rak, and Christian Teixido, Dictionnaire de technologie industrielle, conception, production, gestion, maintenance, Paris: Foucher (Plein pot dico), 1996.

Glossary of the procedural model:

Apparatus: the set of devices and material elements in which exists a structural transformation that organizes the communication between different positions.

Dispositif: the set of all physical elements (material components and human being) that are directly or indirectly in relationship with the structural transformation for any reason whatsoever.

Source: the physical object that is the input material for the structural transformation.

Transitoire observable: the output material of the structural transformation.

Texte-auteur: the set of signs somebody can perceive on the source.

Texte-à-voir: the set of signs somebody can perceive on the transitoire observable.

Author: the position relative to the apparatus occupied by a human being who creates the source.

Reader: the position relative to the apparatus occupied by a human being who only directly accesses the transitoire observable without any other instrument.

Narrow reading: the Reader’s activity involved in the production of the transitoire observable.

Meta-reader: the position relative to the apparatus occupied by a human being who can access all parts of the dispositif.

Profondeur de dispositif: all the elements specific to an individual or a role, but external to the dispositif, which impact their perception, interpretation and action.

Footnotes

-

Litterally: device depth ↩

Cite this article

Bootz, Philippe. "The Praxis of the Procedural Model in Digital Literature, Part 1: Structural Aspects of the Model" Electronic Book Review, 8 December 2024, https://electronicbookreview.com/publications/the-praxis-of-the-procedural-model-in-digital-literature-part-1/