Third Generation Electronic Literature and Artisanal Interfaces: Resistance in the Materials

What is the role of hand-crafted literary interfaces in a world of memes and bots? Kathi Inman Berens examines five recent books that address literary interfaces and applies pressure to the definition of "third generation electronic literature," exploring the role of code and intention in e-lit authorship.

When I’m teaching students to build websites in HTML and CSS, I hear the Prince song as I tell them: “tonight we’re gonna program like it’s 1999.” HTML is a display language, not programming, but I like how the syllables of “program” scan for “party.”

What is the role of hand-coded, artisanal e-literature in today’s corporate Web, where browsing is branded through intermediaries like Facebook and Google? Rather than browsing the open Web, a click inside of the Facebook app redirects within the app to a Facebook-hosted version of what one clicked on. In this sense, social media platforms are slick versions of annoying websites that disable the “back” button by running a redirect script to trap you on the site. “When you tweet, and when you read things on Twitter, you don’t need to use the Web; you can use your phone’s Twitter client,” Nick Montfort observes. “Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat would be just fine if the Web was taken out behind the shed and never seen again.”

Montfort’s “A Web Reply to the Post-Web Generation” responds to Leonardo Flores’ classification of “third generation” e-literature, a genealogy Montfort redescribes as

- Pre-Web

- Web

- Post-Web

“The Web is now at most an option for digital communication of documents, literature, and art,” Montfort notes. “It’s an option that fewer and fewer people are taking.”

Can we even compare first- and second-generation e-literature to what Flores classifies as third-gen e-literature? Third gen’s many millions of artifacts “come from users of multimedia authoring software—such as Instagram, Snapchat, Imgflip, and apps that allow you take or upload a picture, put language in it, create an animation, and share it… . Whether they know it or not, they are producing third generation electronic literature,” Flores says.

This raises a very interesting question about authorial intention in e-lit. For Flores, the artifact’s effects are sufficient to qualify third-gen as e-literature. It’s just a shift from print modality to digital streaming modality, and Flores sees no justification for a bias against contemporary hyperreading practices. Similarly, Matthew Kirschenbaum observed at the end of his keynote address at the 2017 Electronic Literature Conference: “Computers don’t have to be kinetic, interactive, multi-modal, non-linear, stochastic, or aleatory. But we associate them with such in order to validate certain institutionally amenable figurations” of e-lit, things like aesthetic difficulty and hand-coded, artisanal interfaces. Flores and Kirschenbaum call forth an “ordinary” e-lit woven into the everyday: “the plain as opposed to the exceptional or the surprising or the dense” (Kirschenbaum).

To read e-literature’s “dense” materiality is to read heuristically, through trial and error. This is at odds with naturalized, unself-conscious reading in social media, where in microseconds people read and respond with the flick of a thumb. Such ergodic engagement meets Aarseth’s definition of “trivial.” Touch is entirely prescribed by the social media interface (a “like,” a repost, a comment). In my essay “E-lit’s #1 Hit: Is Instagram Poetry E-literature?” I say that reading only the Instagram poem is like reading a greeting card; but to read the many surfaces of Instapoetry enmeshed in user comments and Instagram metadata (some visible, some hidden) is to reckon with Instapoetry’s medial complexity.

Some e-lit artists and scholars object to classifying “third-generation” output as e-literature. Such skepticism moves beyond veneration of artisanal code to a mistrust of unironic use of corporate, profit-driven platforms. In this sense, netprov would be second-gen e-lit because it uses social media self-consciously and ironically. What distinguishes the aesthetic of Lazy Cat txting, which Flores uses as an example of third-gen e-lit, and the Make America Great Again memes, detailed at length in the report Tactics and Tropes of the Internet Research Agency produced by New Knowledge scholars at the behest of the United States Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, which found extensive evidence of Russian cyberterrorism before and during the U.S. 2016 presidential election? As scholars explore Flores’s third-gen framework, to explain how third-gen e-lit is not propaganda, or something else, will be part of defining the classification’s credibility and coherence. There’s a corporate apparatus and profit-motivated agenda that makes third-gen e-lit so easy to make.

At base such scrutiny involves asking: is e-literature output and circulation? Or is it messing around in code, and authorial intention? Is it reception or production? Such questions animate other avant garde conceptual art: one thinks of Kenneth Goldsmith’s “uncreative writing,” such as his remix of Michael Brown’s autopsy. Brown was the African-American eighteen-year-old harassed and then fatally shot six times by a white policeman, Darren Wilson, in Ferguson, Missouri in August 2014. Riots ensued. Goldsmith’s practice of reframing “found” texts as poetry is clearly an act of authorial intention. Many e-literature artists and scholars, conversant in post-structuralism and steeped in literary modernism, reject the notion of authorial intention. A text has agency beyond what the author wants it to mean.

What if “intention” isn’t a telos arced toward fixed meaning, but the materiality of making: heuristic coding, messing around? What if “intention” doesn’t manifest in literary interpretation but simply in the conscious choice to make e-lit?

Consider “Try it Yourself,” the signature feature of W3 Schools’ code tutorials. Eschewing instructional videos or a human voice guiding one through the how-to, W3 Schools simply gives you a code snippet. You click a green button marked “Try it Yourself,” the script runs, the browser refreshes, and you see what the code renders. If the output looks like it might possibly work, you copy and paste it into your own code. You do this many times, hunting strings typed into a search bar, or Stackoverflow or, as one of my students put it, “some random place I couldn’t tell you where.”

Try it Yourself as e-literary intention is consistent with Flores’ definition of third generation e-literature because, as the technical barrier-to-entry lowers, a wider range of people are empowered to “try it yourself” making digital art. They “reject or are unaware of” e-lit’s aesthetic of difficulty. “Try it Yourself” doesn’t prescribe an aesthetic. It discloses an intention. Maybe that intention is to make something funny that gets reshared millions (or maybe just hundreds) of times. This would be valid work of third-gen e-lit because the maker intended for the work to be “read.”

“Try it Yourself” as an intention unifies five fascinating books about ergodic literary interfaces. From the joy-in-making that thrums through Scott Rettberg’s Electronic Literature to the menace of the ubiquitous Metainterface—the virtual “cloud” that mediates nearly all human networked contact and deliberately disappears—my reviews of these books ask what literary interfaces tell us about the stakes of reading and literary play in a “third-generation” networked world. For Christian Ulrik Andersen & Søren Bro Pold, electronic literature is a bulwark against incursions into privacy and agency made by “metainterfaces” that refuse accountability for their destructive effect on social harmony.

My perspective on why these five books are valuable is informed by Sharon Marcus and Stephen Best’s 2009 essay on surface reading: “Surface is what insists on being looked at rather than what we must train ourselves to see through.” Surface is a point of encounter. Attention to the surface is a practice of critical description, more akin to a Geertzian “thick description” than a Jamesonian dive into a text’s hidden ideologies made legible through close reading. Reading third-gen e-lit as I did in my Instapoetry essay is surface reading. By contrast, first- and second-gen e-lit blossoms under the warm light of close reading, as I did of Shelley Jackson’s SNOW and Jim Andrews’ “Seattle Drift” in my ebr Instapoetry essay.

I validate surface reading of literary interfaces because there are many important things at this cultural moment we can see things right there on the surface. For example, you don’t need to dig deep to see the motive and even the strategy orchestrating Russian cyberterrorism leading up to the 2016 U.S. presidential election. These five recent books of electronic literature scholarship move between reading surface and depth, and help us to understand why artisanal e-literary interfaces should be freshly relevant at the moment of third-generation-rising.

- Electronic Literature, by Scott Rettberg

- The Book, by Amaranth Borsuk

- Liberature: A Book-bound Genre, by Katarzyna Bazarnik

- Reading Project: A Collaborative Analysis of William Poundstone’s Project for the Tachistoscope {Bottomless Pit}, by Jessica Pressman, Mark C. Marino, and Jeremy Douglass

- The Metainterface – The Art of Platforms, Cities and Clouds, by Christian Ulrik Andersen & Søren Bro Pold

In addition to being erudite, these books by authors living in Poland, Denmark, Norway and the United States are pleasurable to read. I sequence them to tell a story from general to specific and back again: from a definitive overview of electronic literature (Rettberg), to the material history of the book (Borsuk), to playable books as genre (Bazarnik), to a close reading of one e-lit work from three vantages (Pressman, Marino and Douglass), to a critical treatment of mobile, pervasive interfaces (Andersen and Pold).

In Electronic Literature (Polity: 2018). Scott Rettberg offers a definitive introduction to e-literature suited for classroom use and field overview. Rettberg’s comprehensive vision attends to origin stories that make the claim for e-literature as an essential component of 21st-century literature and art by connecting e-literature to print-borne avant-garde literary movements such as surrealism, Dadaism, Flarf, concrete poetry, and metafiction; and to performance art movements such as the Situationists, psychogeography, Happenings, and various installation artists. Compendious in scope and playful in tone, Electronic Literature is that rare book that can teach things both to specialists and newcomers, inviting everybody to the banquet that is e-literature’s generic diversity. “The Internet is the most important contemporary communication network, but earlier discourse networks, such as the postal system, have also been used for literary art” (156) Rettberg writes, noting postal art as a precursor to network fictions such as netprov, cellphone novels and codework.

This is just one early example in the book of how “commerce-driven communication technologies can be configured as venues [where] the network can take the place of the gallery.” The history Rettberg traces from local or embodied spaces to networks, is structurally replicated in chapters on “Hypertext Fiction” and “Interactive Fiction and Other Gamelike Forms.” E-literature is perhaps still most associated with hypertext in the cultural imagination, which Rettberg calls “a strange situation” because it’s “the genre that has been most written about in the field while simultaneously the genre least actively pursued by writers in recent years” (86). (Don’t worry, Twine fans: Rettberg devotes a good chunk of the “IF and Other Gamelike Forms” to discussing this open-source hypertext framework and community, which Rettberg depicts in his discussion of Porpentine’s works as a lovechild between hypertext and interactive fiction.) The traffic between community formation and technopoesis is an abiding theme of this book, attending carefully to who made what and when. That kind of documentation is especially important because e-literature works are highly ephemeral. Rettberg masterfully charts a field of literary influence with emphasis on nodes; his work distantly reading e-literature dissertations and citational practices, and his curatorial practice of exhibiting significant media archeological archives such as PO.EX, supplies a bird’s eye view of a field that Scott Rettberg knows intimately, having founded the Electronic Literature Organization in 1999, an organization now global and multilingual. “In spite of the short life span of many works of electronic literature,” Rettberg notes, “genres of electronic literature don’t die, nor do they fade away. It is more appropriate to consider how genres and forms…serve as building blocks for other forms that follow them” (201).

One implication of Rettberg’s comment on genre is that the traditional literary standard for canonicity is imbued with the technopoetics of print as a durable technology. Amaranth Borsuk’s The Book (MIT Press Essential Knowledge Series: 2018) historicizes “the book” as a medial creation space whose capacities stretch beyond genre or canon in a well-scoped, -designed and -executed “pocket” book written in accessible language. Like Rettberg’s book, Borsuk’s is also ideal for classroom use. The book ushered forth a number of significant and enduring literary relations: between author and reader, author and publisher, publishers and readers. Borsuk grounds each chapter in book materiality; the first, “Book As Object” includes hand-drawn illustrations depicting the evolution of writing technologies. Chapter two, “Book as Content,” focuses on the book as “body,” an “intimate” space, and attends to the paratextual cues that have evolved over time and made the book a remarkably efficient random-access interface. (I like Borsuk’s clever demonstration of a pointing-finger manicule on p. 87).

An avant-garde poet herself, Borsuk’s chapter on “The Book as Idea” distills how artists’ books depart from the book-as-commodity. The book is a surprisingly stable category given the bold experiments with book size and today’s multiplication of commodity formats. “Amazon offers us the same ‘book’ in paperback or Kindle edition, at slightly differing prices … . When books become content to be marketed and sold in this way, the historic relationship between materiality and text is severed” (112). Borsuk tours through artists’ books by William Blake, Stéphane Mallarmé, Ed Ruscha, Ulises Carrión, “theatrical” bookmakers like Fluxus artist Alison Knowles, and Bob Brown’s “Readies.” Her personal fascination with computational book arts manifests in this chapter’s extended rumination on moveable books of all sorts: the recombinant poetics of Queneau; CYOA books, flipbooks and unbound books; and “ephemeral” books, such as Marcel Duchamp’s wedding present to his sister, a geometry textbook to be suspended by strings from a balcony during their honeymoon in Buenos Aires, “where the elements would gradually wear away at it” (185). Borsuk’s emphasis on book materiality moves discussion of “the book” away from well-worn notions of books as “a space of fixity, certainty and order” (194) and springs the radical potential, in the digital era, inherent in a stable publication format. Borsuk’s untaming of the “book” is evident in both grand and quotidian gestures, such as noting the Renaissance readers who used the book as a storage system: “pressing flowers, copying recipes, keeping photographs, compiling clippings”—personalizations that persist today. “Defining the book involves consideration for its use as much as its form,” Borsuk argues. “Our changing idea of the book is co-constitutive of its changing structure” (195).

What are the definitional implications of books’ changing structures? Katarzyna Bazarnik’s Liberature: a Book-bound Genre (Jagiellonian University Press: 2016; Columbia University Press distribution 2018) culminates two decades of work as both book arts practitioner and theorist. The “b” in liberature draws attention to the book’s active role in co-producing literary meaning with readers: print-bound technotexts. Popular versions of liberature in English include Danieleweski’s House of Leaves, Johnson’s The Unfortunates and the amusing graphical oddities of Sterne’s The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy. The preëminent Polish liberatic author, poet Zenon Fafjer, launched his career with the liberatic poem Oka-leczenie [“Mute-Eye-late;” “healing/hurting of the eye]” (2000, co-authored with Bazarnik); and his 1999 manifesto “Liberature: Appendix to the Dictionary of Literary Terms.” The manifesto sparked a literary movement that Barzarnik’s book classifies as a genre. In Liberature: a Book-bound Genre, Bazarnik tests generic parameters, taking up phenomenology debates of mid- and late-twentieth century about how sequential space supports reader decoding, and more recent scholarship of genre that examines why generic boundaries are unstable but still useful. Bazarnik defines liberature as “spatialized, multicoded writing inextricably bound up with the material form of the book” (46). Bazarnik’s focus on physically playful books pivots on spatial metaphors: book as “meaningful space,” “navigating device,” “buildings” and “bodies.” These spaces are made meaningful by the creative ways they require people to read (in sections on book as “event” and “performative space”).

Bazarnik’s definitional work in parts one and two sets up the final section on “The Question of Genre.” This one challenges fundamental principles of e-literature scholarship because, as Rettberg’s book and many others make clear, technotexts’ generic parameters can be vanishing points. Bazarnik defends the value of genre as “an important analytic instrument” (110) of technotexts because genre is a common “frame of reference” that rewards efforts to “modify regulatory conventions in the literary field” (117). In her survey of genre’s theoretical contexts, Bazarnik finds common ground by yoking genre to readerly performance, a “repeated verbal behavior that is meaningful in social situations … a way of doing things in the world” (168). This relational, contextual definition of genre makes good sense, and does battle with strict enforcement of generic markers that invalidate liberature as “too liberal to be functional in any serious sense” of literary classification (21). One can finish reading Liberature: a Book-bound Genre and wonder why genre is a noun, a thing, as opposed to an adjective: liberatic qualities of engagement. Agnieszka Przybyszewska proposes grading a technotext’s playable properties as varying degrees of liberatic encounter, as do other scholars, including myself. Bazarnik’s turn to interactive reading validates liberature as genre, refurbishing genre for an age when reading is interactively heterogenous.

If Bazarnik aims to situate liberature using existing generic tools, Reading Project: a Collaborative Analysis of William Poundstone’s Project for Tachistoscope {Bottomless Pit} (University of Iowa Press: 2015) underscores the limitations of strict classification in parsing even one e-literary work. Collaborative authors Jessica Pressman, Mark C. Marino and Jeremy Douglass braid together media archeology, critical code studies and visualization as they exfoliate William Poundstone’s Project for Tachistoscope {Bottomless Pit} (2005). Attribution matters in Project, but the authorial divisions are deliberately, productively messy. Identifying who wrote what discloses the edges of expertise and allows readers to chart the progress of the authors’ mutual influence. Writing very much for each other, such openness requires emotional “vulnerability” (140) as discoveries “reroute individual interpretive efforts and [lead] to group epiphanies” (138).

The result is a suspenseful book of literary criticism. Chapter one teaches the reader how to read media archeology, visualization and Flash. Chapter two excavates the tachistoscope as a media instrument and Flash as an authoring tool. In chapter three, Douglass’s “core samples,” volumetric readings of Project’s screen output, segue into readings of the “optical unconscious” and the “detritus” of Poundstone’s code, a materialist reading of authorial intention where .fla files [production files] are an “archive of writerly process and intention” (79). Chapter four, “Subliminal Spam,” is the analytic pièce de résistance where the critical limitations of any one vantage on Project dramatically play out then give way to a satisfying synthesis. “I had been foolish to rely too much on my eyes,” Douglass confesses. “Project’s fixed sequence of words had been flickering by me the whole time, disappearing behind video frames and hiding in low contrast black-on-black changes. On reflection, I realized that [his and Mark’s] conflicting viewpoints lead to greater understanding” (97) because the results were neither random, nor fixed, but both: an insight that siloed expertise would not have yielded. Reading Project: A Collaborative Analysis shows that “collaboration is not just a trendy practice but a powerful sea change in academic knowledge work” (140).

In The Metainterface – The Art of Platforms, Cities and Clouds, Christian Ulrik Andersen & Søren Bro Pold track what it means that “today’s cultural interfaces disappear by blending immaculately into the environment” (10) and propose net art and e-literature as materially self-conscious practices that reveal “fissures” in “habitual” (159) ubiquitous computing. What is the “metainterface’? It’s the movement of human/computer interaction from the desktop to the smartphone and cloud. Humans are both agents and quarry, where they use smartphones to electively inscribe themselves on the network, but also shed enormous quantities of data harvested by media companies such as Facebook and Google. For Andersen and Pold, e-literature resists the mostly invisible ways interfaces manage us. Chapter one renovates Benjamin’s theory of art’s “tendency” to reveal “fissures” in the smooth surfaces of technical revolution (24). Resetting Benjamin’s “The Author as Producer” essay in our contemporary media ecosystem, where shifts in the culture industry preview the broad shifts from owning to licensing, sharing and leasing, we see loss of ownership as also a loss of the vernacular web, and the privacy it fostered. Chapters two, three and four canvas a range of metainterface manifestations: cloud-based computing as a “grammar” of interface aesthetics and algorithms that anticipate behavior (chapter two); the ongoing “territorialization” of the urban landscape (chapter three); cloud interfaces touching everything (general) everywhere (global).

Fissures made visible by art call attention to the evitability, the choices, that undergird our engagement with technical architecture. Metainterface highlights many art interventions that make labor and production visible in examples such as Super Mario Clouds (Arcangel, 2002), Summer (Olialina, 2013), Toxi*City (Coover and Rettberg, 2014) and SNOW (Shelley Jackson, 2014-present), among others. Metainterface also surveys how a database art can intervene in the war on terror or climate change by using “interface tactics” for reading (172, emphasis in original). A final chapter on “Interface Criticism By Design” teases out how self-conscious interface design shuttles between use and context. Articulated in case studies of the Poetry Machine (Andersen, Pold and others 2012-present), and A Peer Reviewed Journal About ___ (Cox, Andersen and hundreds of participants, 2011-present), this final chapter shows the radical potential of mindful interface design as an intervention in the black boxes and hidden processes that characterize corporate-owned metainterface materialities. In both cases, participatory design disseminates interface critical thinking beyond academe to rock festivals, public libraries, and the ordinary browser. It changes how we construe what I’m calling, pace Andersen and Pold, “cloud literacy.”

If Andersen and Pold are right that net art and e-lit can spike cracks into the glassy surfaces of the metainterface, it seems to me that a little bit of code knowledge, coding a webpage in HTML and CSS for example, might whet appetite for artisanal literary interfaces. It wasn’t that long ago—a decade?—that people had to know at least how to jump into a c-panel and figure out a target element to insert an image into a blog post. Now, with Wordpress 5, the “Gutenberg” block editor makes it so that even embedding an iframe is just a click—no need to look at the embed code at all, let alone the code illiteracy facilitated by publishing in social media.

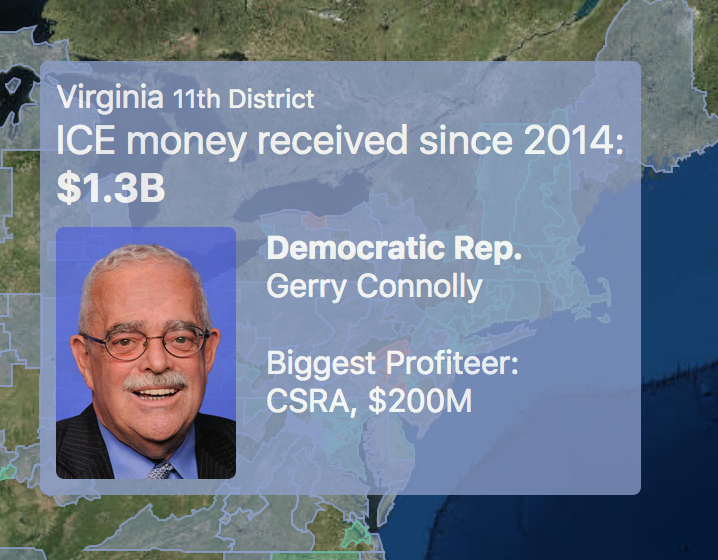

My impression, reading these five books and ruminating on networked social computing from inside the dark forest of Trump’s governance, is that the call to “RESIST” can manifest in messing around. That said, I wouldn’t want to minimize the ways digital humanists are actively resisting Trump administration policies, such as Volume 2 of Torn Apart / Separados, “a deep and radically new look at the territory and infrastructure of ICE’s financial regime in the USA. A data & visualization intervention [that] peels back layers of culpability behind the humanitarian crisis of 2018.” The makers of this website are not messing around, nor are the people their investigations expose: the website visualizes data disclosing which U.S. Congressional politicians have accepted billions of federal U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement [ICE], money that built the infrastructure to detain and separate refugee families. How did these activists collect this information and publicize it? “We mobilize humanities faculties, libraries, and students with relevant language, archival, technical, and social expertise to nimbly produce curated and applied knowledge.” The lead developer makes that work visible and accessible: he “hand-cranked the code for most of what you see here.” As humanists, part of our job is to connect literary art to conditions of everyday life. Increasingly, as the “metainterface” shapes how power propagates, literary and literacy are staged in computational terms. A computationally literate populace would be better equipped to challenge the metainterface, cyberterrorism, and algorithmic oppression; it’s beyond the scope of this essay to discuss relevant books by Annette Vee and Safiya Umoja Noble: Coding Literacy: How Computer Programming Is Changing Writing (Vee, 2017) and Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism (Noble, 2018).

Kirschenbaum’s evocation of the “every day,” the ordinary: this is why I teach my students HTML and CSS (and a little bit of JavaScript): how and why files need to be grouped in a folder in order to load a page; how a directory works; how to transfer files using an FTP client; why one must reload those files if you make changes. Resistance is in the materials. There’s freedom in the small, good thing that is a hand-coded webpage where the author makes every single decision about how that page displays and operates. “Why did people who communicate and learn together, people who had the world, leave it, en masse, for a shopping mall?” Nick Montfort laments of the rise of Facebook and the diminishment of blogs (2014).

How many of next fall’s incoming freshmen, the class of 2023, will have had cause to learn HTML? Or even to have “viewed source”? Some of my graduate students cut their teeth in HTML modifying MySpace pages. In today’s virtual lounges of teen hangout—Discord, House Party, Fortnight, Snapchat—“customization” means kitting out your avatar in premade filters or skins. It’s not kids’ fault that modding in the third-gen is shopping, not coding. But just because kids have less reason to code doesn’t mean they don’t want to make things. Third-generation e-lit is an accessible pathway in. Second-generation e-lit interfaces have things to teach them. Artisanal electronic literature interfaces are more accessible to people who make webpages and “try it yourself.” If third-generation populism is e-literature, then we must also teach students the corporate, material conditions of third-gen e-lit: the intention, not just the output.

WORKS CITED

Ahmed, Manan, Alex Gil, Moacir P. de Sá Pereira, Roopika Risam, Maira E. Álvarez, Sylvia A. Fernández, Linda Rodriguez, Merisa Martinez. Torn Apart / Separados Volume 2. http://xpmethod.plaintext.in/torn-apart/volume/2/index 2018 and ff.

Andersen, Christian Ulrik and Søren Bro Pold. The Metainterface: The Art of Platforms, Cities and Clouds. (Cambridge, MA: The M.I.T. Press). 2018.

Bazarnik, Katarzyna. Liberature: A Book-bound Genre. New York: Columbia University Press. 2018. Book [U.S. distribution of original publication by Jagiellonian University Press, 2016].

Berens, Kathi Inman. “E-Lit’s #1 Hit: Is Instagram Poetry Electronic Literature?” ebr [electronic book review] https://electronicbookreview.com/essay/e-lits-1-hit-is-instagram-poetry-e-literature/ 7 April 2019.

Best, Stephen and Sharon Marcus. “Surface Reading: an Introduction.” Representations 108 (fall 2009) 1-21.

Borsuk, Amaranth. The Book. (Cambridge, MA: The M.I.T. Press). 2018.

DiResta, Renee, Kris Schaffer, Becky Ruppel, David Sullivan, Robert Matney, Ryan Fox, Jonathan Albright, Ben Jonson. Tactics and Tropes of the Internet Research Agency. (New Knowledge) 2018. Report produced for the United States Senate Select Committee on Intelligence. https://www.hsdl.org/c/tactics-and-tropes-of-the-internet-research-agency/

Flores, Leonardo. “Third Generation Electronic Literature.” ebr [electronic book review] https://electronicbookreview.com/essay/third-generation-electronic-literature/ 7 April 2019.

Goldsmith, Kenneth. Uncreative Writing: Managing Language in the Digital Age. (New York: Columbia University Press) 2011.

Kirschenbaum, Matthew. “ELO and the Electric Light Orchestra: Lessons for Electronic Literature from Prog Rock.” MATLIT: Materialities in Literature 6:2 (2018): 27-36.

Montfort, Nick. “The Facepalm At the End of the Mind.” https://nickm.com/post/2014/07/the-facepalm-at-the-end-of-the-mind/ 13 July 2014.

_____. “A Web Reply to the Post-Web Generation.” https://nickm.com/post/2018/08/a-web-reply-to-the-post-web-generation/ 26 August 2018.

Pressman, Jessica, Mark C. Marino and Jeremy Douglass. Reading Project: A Collaborative Analysis of William Poundstone’s Project for the Tachistoscope {Bottomless Pit}. (Iowa City: Iowa University Press) 2015.

Rettberg, Scott. Electronic Literature. (Cambridge: Polity) 2019.

Vee, Annette. Coding Literacy: How Computer Programming Is Changing Writing (Cambridge: The M.I.T. Press) 2017.

Cite this article

Berens, Kathi. "Third Generation Electronic Literature and Artisanal Interfaces: Resistance in the Materials" Electronic Book Review, 5 May 2019, https://doi.org/10.7273/c8a0-kb67