Thoughts on the Textpocalypse

Davin Heckman offers thoughts on Matthew Kirschenbaum's now well-known essay in The Atlantic, The Textpocalypse (2023). Contemplating our own limits in digital media scholarship, including the reinforcing of technological determinisms, Heckman discusses the concept of transindividuation and its relationship with technology, or, the process of becoming an individual through participation in culture and society.

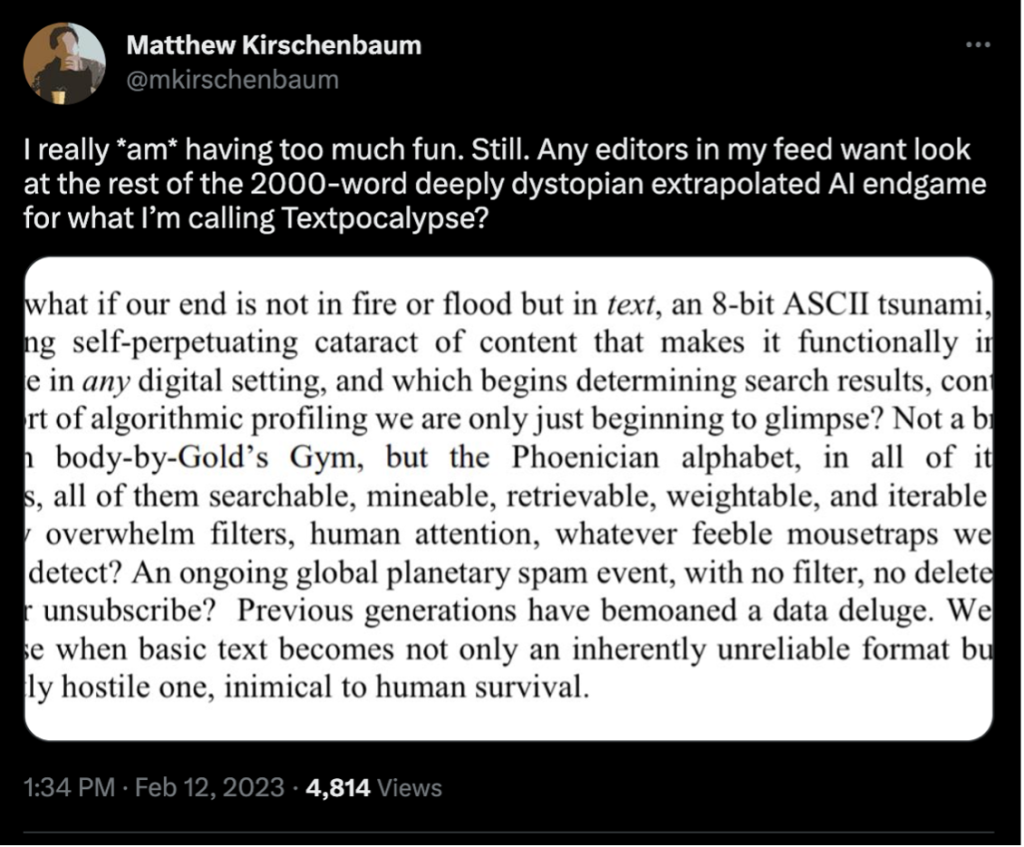

I encountered Matthew Kirschenbaum’s “Prepare for the Textpocalypse” in real-time, hot on the heels of a lively discourse on Twitter. The starting point of this conversation was a February 12th tweet about a dystopian future of AI run amok. (I must confess, I, too, have a deeply dystopian AI endgame in my docs folder, as do, I suspect, many others. And, like many who are reading this, I also jumped into Kirschenbaum’s #textpocalypse Twitter stream with my own dark imaginings.) From there, the conversation ranged as things tend to do on Twitter and culminated in the March 8 essay published in The Atlantic.

https://twitter.com/mkirschenbaum/status/1624854560450772993?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw

Kirschenbaum’s piece is what you might expect from an essay in The Atlantic: It is brisk a piece of prose, well-written and timely, crafted for a popular audience. But what it lacks in footnotes and scholarly formulas, it makes up for with clear insights and a broad awareness, something that I have come to expect from Kirschenbaum’s work.

The argument can be summed up rather simply. Large Language Models (LLMs) like ChatGPT exposes us to the possibility of ubiquitous and ever-growing streams of machine generated content. And Kirschenbaum notes, “That enormous mid-range of workaday writing—content—is where generative AI is already starting to take hold. The first indicator is the integration into word-processing software.” He continues with an explanation familiar to ebr readers that code is also text. And then moves to punchline: As future LLMs feed on the text created in response to previous generations (and fed by content from other LLMs), it will render the domain of human writing increasingly irrelevant as machine generated content engulfs the time-consuming labor of human writing.

As you might expect, this piece generated a number of social media responses, ranging between variations of the adulatory (“Right on!”) to the disparaging (“OMG, Moral Panic!”), and I urge readers to peruse the thread to take in the nuances that I omit here. On the whole, these arguments (and the responses) are not totally unanticipated by people working neck deep in digital culture. And, I know from further conversations, that this is not the extent of Kirschenbaum’s thought on the matter. What matters here is that Kirschenbaum opens an important door.

What we do with this open door depends on what boundary it marks. At times, it seems, our language is a prison-house (to reference Neitzsche’s quote made famous by Jameson) or a whale who holds us in its belly (to reference Orwell’s essay as discussed by Rushdie), in which case the opening presented by ChatGPT and its kin might mark a passageway from constraint to liberation.1 But I prefer to think that the language we historically inhabit might be more like the shire, a familiar place of comfort where we dwell, in which the relatively peaceful linguistic haggling over the fuzzy notions and ambiguous longings gets mapped onto the conceptual artifacts at hand, triumphing over the cruelties that exist where words hold no sway. I believe that more fundamental than popular fears of obsolete careers or sci-fi hellscapes is the notion that our very language and the community that we share it with will no longer serve as our dwelling place. The LLM is the vampire at our door who, once invited in, gains free access to seduce, to feed, and, ultimately, to corrupt the fragile harmony of our domestic refuge. Beyond upended careers and creepy dystopian resonances, they exploit the dynamics of social trust that make life livable and instrumentalize language as an industrial tool for social engineering.

There is a tendency (though not universal) among scholars, especially working in digital media, especially working in the US, to advance only the most modest and grounded claims about digital media (or to simply celebrate the new). The fashion, of course, is for people working in digital media to situate the emergent alongside the history of all other established media as they, too, were once emergent. Of course, the cases that we can examine in these instances are either examples of media success, in which case they were adopted and integrated into a “functional” social model, or examples of media failure, in which case they never functioned or ceased to function effectively and became irrelevant. Even the “bad examples” of media use like propaganda are bracketed off from consideration as either evidence of a failed state (bad!) or part of a functional persuasive apparatus (good!). The process of time, in which the multiple futurities of past moments inevitably fall aside as a singular and unchangeable present, reinforces a kind of determinism. In a society where technology performs a messianic role in the new materialism, such theodicy would be a logical piety.

The systemic reasons for this bias can be harder to get at. An obvious understanding is the legacy of “Limited Effects Theory” that came to rise in American Media Studies during the postwar period. Inaugurated by Paul Lazarsfeld, these strong social scientific approaches sought to measure the impact of media on viewers and came to determine that media play a generally conservative role in society, reinforcing the values of the dominant culture.2 Considering the deep anxieties about broadcast media following Hitler’s rise to power (and the rising Red Menace), these theories were instrumental in mitigating popular fears about audiovisual media and even encouraged their adoption as an instrument for the strengthening American culture. These studies would find willing patrons in the rising media industries of the era, establishing a paradigm for patronage from the Military-Industrial complex and its progeny (depending on who you ask, these might be the Techno-Military-Industrial Complex, Military-Industrial-Academic Complex, Politico-Military-Industrial Complex, etc.). These “sensible” approaches to media came to typify media theory in the US, until it was unsettled in the 1970s by the countercultural turn, continental and post-colonial theories that questioned American hegemony, and the rise of postmodernism. Still, decades of work and deep institutional learning established a framework and tone for scholarly sobriety in media scholarship that persists. And, while the content, technologies and aesthetics of contemporary media industries are very different from those of the 1950s, the basic strategy is still dominant—fund academic research, cooperate with military and intelligence institutions, and appeal directly to consumers through media and markets—and this will temper criticism of your industry.

Apart from the normative inertia of media studies, there are other cultural trends that frustrate media studies from the other end. I call this “Boomerism.” I do not blame the Baby Boom Generation for this tendency, as it is really a strategy to capture the counter-cultural tendencies since the 1960s by making active appeals to youth culture as “the future” and rhetorically placing skeptics on the wrong side (the “old” side) of the generation gap. Under this strategy for cooptation, the idea is to affiliate oneself with youth culture whenever possible as a way to ingratiate oneself with a desirable demographic group.3 “The Kids Are Alright” is a popular trope that is used to defend emerging media practices by framing critiques as attacks on youth, and then “white knighting” to defend the practice. This line of appeal resonates with a popular desire among all the generations that follow to be youthful themselves and adopt the emerging practices of their juniors as their own. This tendency is also a factor that frequently limits our ability to supply negative critiques of new media practices.

Closely related to “Boomerism” are the host of fan-centered approaches that sprung from interpretations of Michel deCerteau’s discussion of “poaching” and “bricolage,” which was radical at its inception and early application by cultural studies scholars. Subsequently, de Certeau’s conception of the resistant aspects of the everyday have been boiled down, in some cases, into a meek celebration of consumer practice. And the practices of fan communities and small acts of making do are now subjects of surveillance, analysis, and service by corporate entities.

Finally, there is the lurking presence of the Left-Right dichotomy in contemporary US politics. Perhaps this owes to the fact that academia, media, and tech industries overlap significantly with the upper-middle class segments of the American political Left, leading to some ideological commonalities shared by techno-utopians, media professionals, and scholars. Gone are the days when Herman and Chomsky, McChesney, and Bagdikian were common touchstones for the US Left (notable contemporary scholars willing to make hard critiques include Safiya Noble, Wendy Chun, Rita Raley, Jennifer Rhee, and McKenzie Wark, though Left critique tends to get subsumed into calls for “reform”).4 The inability of the Left to mount a critique of emerging media leaves orchards of low hanging fruit open for critique by a wide range of willing critics. (Perhaps, it is the fear that such obvious critiques would offend industrial patrons at a time when the Liberal and Fine Arts are losing power in Universities and in the culture at large). And since the critics that do appear happen to be on Right and/or populist, this increases the squeamishness about participating in critique for fear of being affiliated with Right wing and/or populist politics. The concern is that in critiquing media systems with any vigor, one is vulnerable to a kind of mimetic contagion that could cast the critic as a rightist (or, even, a Russian!).5 Here, the lobbying of techno-optimists effectively manages to divide and conquer its critics. From here, attempts at criticism are often delivered as carefully modulated calls for media reform.

When it comes to affirmations of emerging media, on the other hand, there is great negligence. We offer the techno-utopians and entrepreneurs wide-berth in the reimagining of every aspect of our society in accordance with highly hyped and oversold pitches. We roll up our sleeves and ponder ways to troubleshoot and debug, explore the possibilities, and bring the tools to new users (“free” iPads to teach kids media literacy). We allow AI to speculate a great deal with probabilistic models to probe for possible futures, solutions, and sequences, both common and uncommon. It is urgent that we open the door of negative speculation in critical digital media studies. We should be free to think about what could possibly go wrong without having to prove that it already has (even when, sometimes, it already has gone wrong). And though there are other voices out there doing the same, Kirschenbaum’s piece comes in the right place and the right time to help frame the reception of a highly hyped piece of popular technology.

In that spirit, I would like to push Kirschenbaum’s critique a bit further. Here, I consider what happens beyond the disruption of writing as an act and to ponder the possibilities of machines reading machines across three interlocking possibilities: The collapse of the language, the proletarianization of culture, and the destruction of the social knowledge base:

Language as commodity and the new great depression.

In The Smartness Mandate, Orit Halpern and Robert Mitchell explain that “smartness is not committed to price as the measure of all things, for the ‘wisdom’ of its distributed populations can also employ nonprice metrics (e.g. page-ranking methods, Wikipedia, etc.)” (223).6 The genius of cash and free markets is that at a small scale they can mediate the difficulties of material existence by making labor, goods, time, and knowledge interchangeable across a common nexus. The consequence of this, of course, is that it has the effect of rendering all suffering and desire as commodities themselves that can be bought and sold. This tends to displace the social dimensions of these experiences, producing alienation. Further along, social power is similarly alienated, and this nexus becomes the site of financial power (and thus exploitation). Finally, pervasive exploitation leads to a default of trust, and the system is subject to collapse.

At first blush, we tend to be heartened and inspired (though just as likely shocked and mortified) by the social (non-cash) value of the digital. Under this, a great many practices can be witnessed and ideas can be expressed (and diminished or enhanced through social and technical mechanisms). So the availability of non-price metrics gives us hope for something more than commodity culture, a hope that is nurtured particularly in Millennial and Zoomer generations who allegedly privilege experiences over things.7 However, we agree that information (harvested by sensors and inputs, processed through analytics and design, and consumed as content) in digital networks has value and that has the potential to quantify this value (through metrics like page ranks, engagement analytics, social credit scores, etc.) and that this value can be monetized (as consumer content for entertainment or instrumental use, for surveillance and prediction, and/or for behavioral control). And, so, a whole range of experiences, from the vast reams of life-data captured from the institutions that we formally interact with to the meandering moments everyday life (including all words written and spoken via digital network) become subject to alienation. Once the public becomes aware of exploitation, this alienation can quickly give way to a collapse of trust. With Snowden’s revelations of mass surveillance, the popular revulsion to social credit scoring systems and online influence operations, and the gathering storm around censorship on social media platforms, the surveillance and behavioral components of this new nexus have been injured. Though these components remain unobtrusive by design, and the typical user is typically drawn into participation for content and communication.

Once the spectacle of unending torrents of really convincing but totally hollow robotic sophistry flood the zone, the value of these spaces as sites for the engagement and expression of meaningful content and communication will continue to degrade at an ever increasing rate. In the absence of personalism, content and communication will accelerate its use of pornographic triggers (like sex, pain, fear, trauma, despair, danger, happiness, etc.) and exploitation of psychopathologies. In other words, there will be a boom followed by a bust. As the saying goes, talk is cheap. But it’s about to get cheaper. Soon, you’ll see people leaving the libraries with wheelbarrows full of words worth less than the paper they are printed on.

The posthuman proletarian and the digital demagogue.

Borrowing from Gilbert Simondon, Bernard Stiegler describes individuation as a process (rather than a goal) that is bound up in the psychic (personal), collective (social), and technical (in this case, recorded) negotiations of daily life. In other words, one’s individuality is not the end goal of culture or society, but rather it is one’s sense of self that is in a constant state of becoming when one participates in the life of the mind, society, and culture.

Rather than the historically loaded term “deindividuation,” the term “transindividuation” preserves the collective character of deindividuation while accentuating the ways in which one’s sense of self does not simply disappear when one enters into affiliation with others. Indeed, for Stiegler, the role of the technical apparatus as the place where tertiary retentions (recorded, archived, and recirculated memory) weave one into the cultural framework of history and the future is where a broad, generalized sense of belonging is brought into contact with the individual’s singular existence. The idea that one matters as an individual is contingent on one’s ability to belong (to be desired and to desire in the present social context, in relation to the past, and in anticipation of the future). In other words, transindividuation does not erase the individual, rather it is why the individual matters.

But Simondon’s take on the human is not simply about what one what will become (ie. posthuman), for in his work, being exists in a pre-individual state prior to the process of individuation. Certainly, human beings existed, participated in culture, and experienced various aspects the individuation process prior to the ideological formation of Humanism and its attendant preoccupation with individuality. To bend a phrase from Latour, perhaps, we can say, “we have never been Humanists.” In which case, we can also say, that one can be posthumanist without being posthuman. On the other hand, being posthuman could be taken to indicate the collapse of human being and the dynamic processes of psychic, collective, and technical individuation that contribute to the experience of ourselves.

This process of transindividuation can be “short-circuited.” Stiegler summarizes this:

Self-produced in the form of personal data, transformed automatically and in real time into circuits of transindividuation, these digital tertiary retentions short-circuit every process of noetic difference, that is, every process of collective individuation conforming to relational intergeneration and transgenerational knowledge of all kinds.

As such, these digital tertiary retentions dis-integrate these psychic secondary retentions of social reality. (Automatic Society, 38)

In other words, the collapse of tertiary retentions (and those secondary retentions expressed via digital networks) disrupt the long-circuits of transindividuation in favor of automated processes. And though Stiegler here is largely discussing social media surveillance and manipulation as mediator of intersubjectivity, these comments gain greater urgency when the dominant subject in the equation is machine intelligence.

To be fair, the popular 20th Century technologies of mass media (radio, television, and film) managed to short-circuit many aspects of individuation, replacing folk practices of music, performance, dress, socialization, and language with prescriptive, commodified forms. But technologies of transmission (even aided by audience research and social science) come nowhere near the present integration of dissemination, capture, analysis, and now expression of content itself. Stiegler explains, “At this stage, it is the mechanisms of transindividuation that are grammatised, that is, formalised, reproductible, and thus calculable and automatable.” (“Within the limits”)

But the underbelly of this is trifold: First, by short-circuiting desire towards quick (typically commodified) objects, we stifle the necessary process of transindividuation. Secondarily, we deprive society of the broader occasion for the pro-social reliance on culture as originating in the social body itself. Thirdly, we foreclose on the possibility that the conduct of one’s life might be considered to have any sort of cultural legacy for others. Under this epistemological paradigm, savoir-vivre (the knowledge of how to live) has been replaced with savoir-faire (the knowledge of how to do). Instead, when we want something, we step to the kiosk, punch in our order, swipe our card, and wait for the food to arrive in a bag. No eye contact, no chit chat, no undesired interaction whatsoever, only quick libidinal gratifications with no space to process those desires in the context of those we live amongst. Already, we can see that people are learning to find unsolicited small talk as a rude interruption (“Nice weather we’re having.” “Leave me alone, weirdo!”). In other words, the social world has become rigged to prefer the shortest distance between desire and fulfillment, with no space for reflection, social interaction, much less historical speculation. Human language is reduced to its sparse phatic function, which mirrors the obligatory gestural signs of empty attention we have learned to apply on social media (Thumbs up!). Furthermore, as individual paths of inquiry themselves are mapped and studied and projected in the form of autocompletions, recommendations, and the occult alterations of your feed, who even needs to seek at all? If you fail to click, comment, or even pause on the prescribed information, this is recorded and adjustments are made, in the hopes that thinking itself is obviated by fulfillment. Soon, even our thoughts will steer the guided tour of our customized machine generated reality. Following the industrialization of culture and our consequent de-skilling, we will be subject to “cognitive and affective proletarianization” (Stiegler, For a New, 45). In other words, culture, sociality, and psychology will become posthuman, not as some ideational “-ism” which we choose to adopt (though many may), but as an epiphylogenetic event.

And from the ashes of the great semiotic crash of 2024, the demagogue that rises will not be a weird orange man, it will be an atmospheric voice barking in our brains. Our head in the clouds, we will sdream a utopia in which we seize the means of production of meaning and declare a perpetually beta-tested revolution. The algorithms automatically filter and ban all enemies of the state of consciousness, giving rise to a new world where all can binge according to their ability and shitpost according to their need.

The replacement of the social knowledge base.

Following on Stiegler’s discussion of transductive individuation, I wish to reflect on what makes a person into an intellectual, or more generally, what makes a wise person wise. Being an intellectual is not about putting everything into one’s mental library (though it does require mastering something). More important than mastery is self-awareness about one’s provincial little mental library married to a humble curiosity about what is contained in the libraries of others. The skill of the wise person is to seek and appreciate what’s in another person’s mental library and how they use it. This is why we build universities, to create a repository of living libraries (augmented by actual libraries) and to make them available to a community of scholars, their students, and the civilizations they serve. But this repository of dynamic knowledge is not confined to the university. Wisdom exists in the city, in the village, in the family, in churches, in workplaces, etc. In other words, intellectual life rests on the possibility not just of individual intellect, but on the formation of a social knowledge base, or the aggregation of knowledge and analytic capacity of the community. And, when a living community envisions itself as a transgenerational entity, it gathers up information from the past generations and conserves for the future generations, using technologies and techniques of memory, to build an archive. And this integration of the individual, community, and culture is foundational to meaning in civilization.

As one can glean from Elon Musk’s recent acquisition of Twitter, there are deep lessons to be learned about the looming crisis of cultural proletarianization. Set aside the specific criticisms of Musk himself, and we have a perfect case study of what happens when the intellectual life of country shifts the utopian aspiration of institutions like the University to engineered Platforms and the automated process they are designed to support. Even as American scholars lament the current crisis of higher education, they seem to implicitly consent to the displacement of the social knowledge base as dialogical endeavor in favor of a database curated by black box processes (I would argue that this displacement happened to a great many laborers during prior regimes of economic disruption, but it is a crisis now that “future proof” professionals are being hit). The most common critique of Twitter is that without a cadre of curators serving the gatekeeping function, that intellectual anarchy will prevail. And, perhaps more dangerous, this belief in gatekeeping has trickled down into the logic of the actual brick and mortar knowledge communities. What has been abandoned is any pretense that ethical systems themselves can, on the basis of their own logical consistency and discursive practices, provide a moderating function within a community. Instead, the belief is that even a highly educated group of individuals committed to a common purpose is destined to run itself into the ditch without regulation by a technocratic system of control, particularly when it encounters large numbers of interlopers (not to mention armies of bots). Against this failed community, we have a naked “will-to-power” and lose the internal tendency towards understanding. Of course, social media was never meant to be a community in the first place. Nevertheless, we accept its failure to be what it can never be as proof that actual communities are impossible. The tempest in Twitter’s teapot gives way to a more generalized sense of crisis within culture.8

AI enters as a kind of trusted partner into the crisis of the collapsed social knowledge base. Where communities of actual humans seem to have failed before our eyes, AI can furnish carefully tailored results that seek to resemble the acceptable and desired range of texts that we seek. Thus the technical apparatus has taken center stage, with quick searches yielding definitive “facts,” tutorials and explainers offering the one best way, and truncated distillations of the social world. Even “asking” for help has been made more efficient, as interpersonal negotiation gives way to broad solicitations for help enhanced by algorithmic prioritization of attention. Of course, this is incredibly convenient: Who needs to read when one can search for the precise term? Who needs to coordinate meaning when a direct path is offered? Who needs to know when it can be looked up? Who needs to remember when the live stream is being captured? Who needs to discuss when the “facts” are given on demand?

Pharmakon is generally understood as the etymological root for pharmacology, the science which studies the careful use of substances which, when administered properly produce cure or improperly produce harm. But as Stiegler explains, pharmakon is better understood more broadly as a “transitional object” that disenchants one thing in the process of enchanting something else in its place (“Pharmacology”). This substitionary role (remember, the ancient pharmakon was the scapegoat who was purged as a substitute victim bearing the responsibility for social malaise) is, of course, operative here, both in terms of how LLMs replace the social context of knowledge formation with a model and for its broad liminalizing tendency with an associated stupefying effect on culture.9

As we abandon the grave difficulty of community formations, we will grow accustomed to seeing slick but shallow pantomimes of competence as preferable and will yearn for the AI that can give us what we want. Predictably, a society of proletarianized posthuman subjects would find these narcissistically targeted machine-oracles and their hollow moments of gratification difficult to resist.

Works cited

Castells, Manuel (1996). The Rise of the Network Society, The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture Vol. I. Cambridge, Massachusetts; Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Chun, Wendy. Programmed Visions: Software and Memory (MIT Press, 2013)

De Certeau, Michel. The Practice of Everyday Life. Trans. Steven Rendall. Berkeley and Los Angeles: U of California Press, 1984.

Eagleton, Terry. Literary Theory, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. 1983.

Frank, Thomas, and Matt Weiland, eds. Commodify Your Dissent, ed. New York: W. W. Norton, 1997.

Girard, René. Violence and the sacred, transl. Patrick Gregory. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 1979 [1972]. Girard, René; Tréguer, Michel.

Gitlin, Todd. “Media Sociology: The Dominant Paradigm,“ Theory and Society 6 (1978), pp. 205-24.

Hayek, Friedrich. “The Theory of Complex Phenomena.” (1967) Readings in the Philosophy of Social Science. Michael Martin and Lee McIntyre, eds. Boston: MIT Press, 1994: 55-70.

Heckman, Davin. “The Politics of Plasticity: Neoliberalism and the Digital Text.” electronic book review. 19 February 2013. https://electronicbookreview.com/essay/the-politics-of-plasticity-neoliberalism-and-the-digital-text/

Jameson, Fredric. The Prison-House of Language. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1972.

Kirschenbaum, Matthew. “Prepare for the Textpocalypse.” The Atlantic. 8 March 2023*.* https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2023/03/ai-chatgpt-writing-language-models/673318/

Noble, Safiya Umoja (2018). Algorithms of oppression: how search engines reinforce racism. New York: New York University Press.

Raley, Rita, and Jennifer Rhee, eds. American Literature. Volume 95, Number 2

Published: June 2023.

Rhee, Jennifer. The Robotic Imaginary: The Human and the Price of Dehumanized Labor. University of Minnesota Press, 2018.

Roberts, Kevin (2005). Lovemarks: The Future Beyond Brands. NY: powerHouse Books.

Rushdie, Salman. “Outside the Whale.” Granta. Online edition. 1 March 1984. https://granta.com/outside-the-whale/

Simondon, Gilbert. “The Position of the Problem of Ontogenesis.” Trans. Gregory Flanders. Parrhesia 7 (2009): 4-16.

Stiegler, Bernard (2016). Automatic Society. Trans. Daniel Ross. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Stiegler, Bernard (2010). For a new critique of Political Economy, Cambridge: Polity Press.

Stiegler, Bernard. “Pharmacology of Desire: Drive-based Capitalism and Libidinal Dis-economy.” New Formations. 72 (2011): 150-161.

Stiegler, Bernard. “Within the limits of capitalism, economizing means taking care.” Ars Industrialis. 2 November 2008. http://www.arsindustrialis.org/node/2922

Turner, Victor. “Betwixt and Between: The Liminal Period in Rites of Passage.” The Forest of Symbols. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1967: 93-111.

Wark, McKenzie. Capital Is Dead: Is This Something Worse? (Verso, 2019).

“Circulation can proceed here [within the public sphere] without a breath of exploitation, for there are no subordinate classes within the public sphere—indeed in principle, as we have seen, no social classes at all. What is at stake in the public sphere, according to its own ideological self-image, is not power but reason. Truth, not authority, is its ground, and rationality, not domination, its daily currency. It is on this radical dissociation of politics and knowledge that its entire discourse is founded, and it is when this dissociation becomes less plausible that the public sphere begins to crumble. (17)”

Though, I would argue that this discourse requires a commonly held meta-institution of transcendent value (ie. a common agreement upon what is “true” or “good”). This is difficult to sustain as societies become more pluralistic, thus Hayek’s arguments for market, which can price commodities (not to mention psychological and social needs) whose values cannot be measured by a central authority (much less reliably predicted). Similarly, Manuel Castells’ concept of the “space of flows” is a rendering of currency, not as a static unit of exchange, but as an informational value for the digital age.

Footnotes

-

A long time ago, I attempted to get at the neoliberal “liberation” of meaning from deliberative processes in “The Politics of Plasticity.” As an intellectual hobo, I often gesticulate madly about the inner-workings of skyscrapers, when the truth is that, if I’m lucky, I might make it to the bathroom before being escorted from the premises. Which is another way of saying that my perspective is limited. The best I can do is tell you what it’s like to be escorted from lobby, and, maybe, what it’s like to wash my armpits in sink. But I can’t tell you what the view is like from the penthouse. ↩

-

For a thorough discussion of the rise and dominance of “Limited Effects” research in Mass Communication, see Todd Gitlin’s “Media Sociology” (1978). ↩

-

For a thorough discussion of the capture of counterculture, see Thomas Frank’s Commodify Your Dissent (1997). For specific discussion of the capture of youth culture from the volume, see Thomas Frank and Kenneth White’s essay “Twenty-Nothing” (on pages 194-201). ↩

-

See for instance, Safiya Noble’s _Algorithms of Oppression (2019), Wendy Chun’s Programmed Visions (2013), Rita Raley and Jennifer Rhee’s special issue of American Literature on “Critical AI” (3023), Jennifer Rhee’s Robotic Imaginary (2018) and McKenzie Wark’s Capitalism is Dead (2019)._ ↩

-

For a more thorough discussion of mimesis, contagion, and scapegoating, read René Girard’s Violence and the Sacred (1979). ↩

-

The “smartness” regime is not the first, nor best, attempt at the creation of alternative methods of value and exchange. Terry Eagleton’s comments on the role of criticism within the public sphere are a modern, liberal attempt to establish alternative currency via discourse: ↩

-

A great example of this thinking is Saatchi and Saatchi CEO Kevin Roberts’ Lovemarks, which explains, rather absurdly, that younger generations want brands that they can fall in love with, that speak to them a language of “mystery,” “sensuality,” and “intimacy.” ↩

-

What does it mean that this door was kicked open on Twitter, rather than within the context of scholarly conversation at, say, a conference or in a journal? Such conversations are happening in classrooms and on laptops, but they are modulated by the institutional forces described in this essay, and up until now I have not participated in any without being met with the rote forms of pre-emptive techno-apologetics described in this essay. On the other hand, a stupefied space like Twitter, where hyperbole is performed and expected, exists as a pharmacological substitute in an age where such platforms will perhaps provide “degrees or their equivalent.” ↩

-

Thank the blind reader for teasing this out this aspect of Stiegler’s work in their review. I also owe a debt to Victor Turner’s “Betwixt and Between: The Liminal Period in Rites of Passage” for my understanding of liminality. ↩

Cite this article

Heckman, Davin. "Thoughts on the Textpocalypse" Electronic Book Review, 7 May 2023, https://doi.org/10.7273/6hjd-mp06