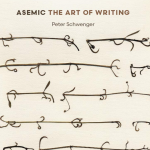

"Tracing the Ineffable":a review of Peter Schwenger’s Asemic: the Art of Writing

In this review of Asemic: The Art of Writing, Diogo Marques considers alongside author Peter Schwenger the seemingly asemantic style of asemic writing as a genre taking on new meaning in contemporary reading and writing networks, particularly in light of the paradigm shifts they continue to undergo as brought about by digital media.

To write a book on a type of writing characterised by its lack of specific semantic content would, upon first impression, present a seeming contradiction. But perhaps, more critically, it may yet unveil a series of tensions inherent to the nature and purpose of that subject. By exposing and analysing some of those tensions, Peter Schwenger’s latest book sets the stage for a phenomenon often thought of as a particular type of visual poetry, but which is now gaining sufficient prominence to be considered a genre in its own right: asemic writing.

Based on a tension between play and constraint (akin to Roger Caillois’ use of ludus and paidia, respectively), asemic writing is usually described as the purposeful loss of meaning. This loss goes all the way to down to the limit of its minimum indivisible units, expressly, seme, or signs. For Peter Schwenger, an experienced author in the analysis of the materialities involved in writing/reading processes, particularly those related to experimental literature (see At The Borders of Sleep: on Liminal Literature, 2012), appearing “miseffectual” in its unfamiliarity and estrangement does not mean that it does not possess aesthetic and poetic effects of its own. Such effects, including a specific type of “cognitive dissonance” – in the sense that “writing is evoked at the same time that we are estranged from it” (7) – are what prevents us from fully assuming its complete illegibility and, therefore, enabling alternative definitions for what writing (and reading) means.

Easily found (and easily lost) at the fringes of text and image, the “asemic effect,” as Schwenger calls it, is about “suspending the observer in a productive tension” (10). It is interesting to note that, etymologically, the word tension comes from the root ten, meaning “to stretch,” thus connecting it with the idea of strings, or lines. Nevertheless, far from being linear, the strings, or lines, in which language struggles against itself take on a similar role which Sartre attributed to silence as “a moment of language.” They are, therefore, asemically speaking, a kind of absent presence, evinced, for instance, in the way in which circles and spirals, “the typical circularity of a child’s early scribbling” (13), often resemble the umbilical cord (and consequently the irretrievable loss of connection triggered by its cutting).

Tracing the origins of the term “asemic writing” back to its similarities and differences with other poetic forms such as (neo)concrete and visual poetry, the first chapter exposes why, during the 1990s, visual poets Tim Gaze and Jim Leftwich felt “the need” to coin the term “asemic” in the first place mainly as a response to a “crisis” in writing. Interestingly, and as far as tensions go, what seemed to motivate asemic writing cannot be separated from what started by justifying its success. In specific terms, to recognize asemic writing as a “liberatory movement” against logocentric feuds (intensified by the impact of certain media on the technology of writing, namely at the level of word processors, one must add) is to acknowledge the impact of those media in a paradigmatic change at the level of communications (i.e., the Internet).

This recognition brings us to the metareflexive nature of this form of writing. Asemic writing offers an “implicit resistance,” and frequently expresses “its aims under the same banner as that which it resists – a global language” (15). For this reason, Peter Schwenger draws a parallelism with another type of “global language,” expressly, “computer code” – though this comparison between the two does seem a little unbalanced, given that “computer code” already possesses its own disruptive and dysfunctional modes of expression.

Chapter 2 presents yet another type of dialectic tension, specifically a dialogue between “three asemic ancestors” – Henri Michaux, Roland Barthes, and Cy Twombly, respectively – representational echoes of so many other artists/writers who practised “asemic writing” well before it was designated as such. As happens in other chapters, Schwenger does not provide an extensive list of artists or artworks (he makes reference, though, to other prominent figures, such as portuguese Experimental poet Ana Hatherly, in a more than welcome final section titled “Notes,” 155-159). Nonetheless, not only the three names chosen as precursors of asemics holistically combine a series of fundamental characteristics sufficiently stable to define a field but also consummately serve the author’s purpose in establishing a concise treatise on a new type of art/writing that puts Schwenger at the forefront with respect to published academic research on the subject.

Profusely illustrated, this second chapter also evinces the multidisciplinary nature of asemic writing, for instance, its resemblances with dance, but not without exposing substantial differences as well (27-28). Beginning with Michaux’s “lines and signs”, Schwenger then takes a detour that leads us straight to Barthe’s multisensory Contre-Écritures, evoking the “physicality of the hand that creates the line” (42) and contrasting it with a purely visual idea of writing and reading. Finally, with Cy Twombly’s painted “protowriting” (to use Carrie Noland’s term), the reader is at last assured that, within the realm of asemic writing, the bigger the exposure to the kinetic act of inscription, the less legible it becomes.

Equally characterized by an “asemic attitude” (60), but “not necessarily produced by artists,” are the manifestations present in chapter three. Titled “Traces,” this intermediate chapter highlights a series of consonances as well as some dissonances present in the world of asemics. The first subset of these, eco-asemics, identifies nature as a creator, offering the reader the main role in what concerns “intentionality.” Bringing to the surface some of the longstanding problematics usually associated with Found art, “eco-asemics” raises the problem of defining a field or a movement, by which the question of whether it is indeed apt to refer to it as writing (let alone literature) arises. Notwithstanding, Schwenger believes that placing “another sort of meaning, that of writing in itself, beyond any particular content that is conveyed,” is precisely the “view of writing that asemic wants to convey,” with its “essence in the rhythms and gestural relations of marking” (66).

One of Derrida’s major concepts in his deconstructivist critical outlook, trace (in French as well as in English), encompasses a wide range of meanings, including track, path, or mark. For Derrida, trace differs from the sign, in the sense that it is a mark, a track, left by the sign’s absent part. Every present sign is therefore necessarily composed of traces of a defining absence. From Derrida’s trace to eco-asemics is but a small step, since both evoke the act of writing underlining the idea of “absent presence.” As such, given that asemics “conveys something about the nature of writing that is generally obliterated by the verbal message” then “even the configurations of the scripted lines convey a meaning, a gestural equivalent of a psychological disposition at the time” (67, 68), which in turn paves the way for the upcoming of inter and, even, transdisciplinary relations between diverse areas of knowledge (psychology and literature, for example, a convergence frequently explored by Schwenger). However, there is not any “promise (of communication)” that does not bring with it a component of frustration, a “dual movement” that, in the case of (eco-)asemics, “is not confined to specific messages” (71), since it belongs to a much wider scope, that of forms of intelligence in nature and the (im)possibility of a transhuman and planetary language associated with these.

Another meaning for trace brought forth by Schwenger concerns the ways in which there seems to be a pattern in associating asemic writing with “a preliterate experience from childhood” (83), while challenging the school system by which we see the ability to read and write developed. Two examples of such practice may be seen in Cui Fei’s “Tracing the Origin,” in which “tracing” represents a duality implicit in “tracking something down and to the act of reduplicating,” as well as in Xu Bing’s “Book from the Sky,” a series of books in which that duality is taken literally, “with all the apparatuses of a scholarly work, recognizable as such despite their illegibility” (76, 95). It is quite significant that Schwenger makes use of examples by artists of Chinese origin working “within their own culture” and choosing to see their own writing system as “something alien.” This is especially evident in a subchapter titled “The Chinese Connection,” in which Schwenger also explores the idea of Chinese characters as a recurrent inspiration for artists working from a Western viewpoint, for whom these characters are easily “seen as markings floating free from any recognizable meaning” (100).

Part of what contributes to the consolidation of a field are the statements put forth by its practitioners, often through informal channels, such as interviews and e-mails. Presenting a collection of some of the thoughts and reflections by artists who are currently vested in the exploration of asemic writing, Chapter 4 dives deeper into the work of three of these artists, namely Michael Jacobson, Rosaire Appel, and Christopher Skinner. The choice of these particular authors may, however, reveal an apparent incongruity. Considering that this is a book dedicated to a type of art that excels precisely by excluding any recognizable language, it is in fact a little peculiar that its author has opted to highlight three authors that have English as their native language. Asemic writing is surely bound to have its practitioners all over the world (who possibly identify themselves using other designations), though his choice may become attenuated from the moment asemics is recognized as a community in which the author seems to dwell upon with more than sufficient ease – thus justifying Schwenger’s predilection for artists relatively close to his circle.

It can be said, however, that each of these artists represents a unique world of their own, considering the ways in which each one follows a specific set of constraints. Furthermore, as observed with the three asemic forefathers analysed in chapter two, relations with other artistic expressions (noise music, comics, visual poetry, among many others) are an integral part of the creative process by today’s asemic artists. Inevitably, we are led to raise the question: given its consonances (and dissonances) with other arts, is it possible to define asemic writing as its own independent movement, when at the same time it struggles to be pinned down as a fixed and sufficiently clear-cut genre?

Although asemic writing has the potential to suppress any sign and its consequent value, it still retains some of the historical conventions associated with the gesture(s) of writing, whether “calligraphic or typographic asemic” (132). Nonetheless, these materialities, along with those of the page (and codex) invariably explored by asemic writers, are also what allow us to read an asemic artwork. Despite being the shortest chapter, chapter 5 is certainly the most open to new discussions concerning the implications of reading asemic writing, thus confirming the originality and relevance of Schwenger’s approach. To sustain his argument, he resorts to Luigi Serafini’s Codex Seraphinianus, perhaps one of the most scrutinized art(ist) books ever. Ironically and asemically enough though, the repeated attempts at decoding it have only added to its mystical aura, further deepening the mystery surrounding it. Making use of the testimonies present throughout Asemic, Schwenger gives voice to Serafini’s thoughts concerning his personal creative process, for instance, by emphasizing childhood sensations related to writing and reading in favor of the book’s potential as code. Nevertheless, as Schwenger reminds us, the “ultimate dream, of course, is that this apparently authoritative text is capable of being decoded,” this promise of esoteric knowledge being often used as a “strategy” in asemic artworks (140-141) – in this way emulating ancient alchemical treatises to be deciphered only by those worthy of those teachings. On the other hand, although sufficiently open to serve as a catalyst for many more future takes on the subject, chapter 5 also shows us that no matter how illegible, and indeed ineffable, an experience may seem, as wordly beings, to read asemics is always about translating into words “the emotional effect of the marks before our eyes” (146).

Combining a set of rules of engagement as well as constraints based upon specific conventions, asemic writing thrives on a dance between centripetal and centrifugal forces permanently at play and in constant transmutation. In a clear and in-depth way, Asemic: the Art of Writing can be seen as a first official notation of that dance, excelling in the ability to bring to a wider audience the intricacies of a subject often seen as a niche of encrypted doodles legible only to a few.

Cite this review

Marques, Diogo. ""Tracing the Ineffable":a review of Peter Schwenger’s Asemic: the Art of Writing" Electronic Book Review, 6 December 2020, https://doi.org/10.7273/6ynd-yf62