"The Effulgence of the North": An Introduction to the Natural Media Gathering

This collection emerges from a panel hosted by the Modern Language Association's MS Forum on Visual Media (http://naturalmedia.org/titles/) in 2017. "Natural media" re-valuates the communicative potential of natural spaces, especially in instances where symbolic import collides with raw matter in a manner that hides from, disguises, or elides stark reality. It considers intersections, collisions, tensions, opportunities, and affordances that arise in the discussion of "Natural Media," both broadly conceived and in its contributors' particular areas of research. It is also in close conversation with research inspired by a previous gathering on a closely related topic: Digital and Natural Ecologies.

**A Note from the Co-Editors:**This Introduction is in dialogue—literally—with the contributors to the “Natural Media” gathering. Roll over the dialog bubbles embedded in the text to read marginal comments by Karen Bishop, Elizabeth Callaway, Alenda Chang, Zachary Horton, Diana Leong, and Joseph Tabbi.

The remarks were posted in the mysterious pre-publication period after the essays had passed the initial stages of peer review. These exchanges, while somewhat informal in tone and digressive in shape, suggest how thinking-in-practice continues at different stages of the publishing process within an editorial milieu that, like so much of the infrastructure and labor supporting the literary ecology, usually remains obscure.

We debated whether or not to turn some of the longer comments into a separate essay, but decided against it. Eric wasn’t convinced his remarks on Thoreau warranted a separate riPOSTe essay. More importantly, he wanted to convey in the comments how the editorial process leads to research, writing, and conversations that, while marginal, deserve to be valued as necessary intellectual labor.

After deconstruction, the margins were supposed to have been reclaimed by academics as a site of productive activity. But corporatized higher-ed systems have priorities that routinely conflict with necessary intellectual practices. Serendipitous insights and other ways of knowing fostered by marginal communications are, too often, anathema in corporatized academic environments. Though such exchanges are integral to the intellectual development of both the individual and the collective, and can be catalysts for further literary, critical, and artistic innovation, they are under threat in an unimaginatively instrumentalized academia.

For this gathering, then, it seemed particularly appropriate to mediate some of these marginal communications, which strike us as quite, well, natural.

The co-editors, Lisa Swanstrom and Eric Dean Rasmussen, first met in person and began collaborating on the “Natural Media” gathering in May-June 2018 when, at the invitation of Eric and his colleagues at The Greenhouse (an environmental humanities research initiative), the University of Stavanger hosted Lisa as a visiting scholar-in-resident. We are grateful for the institutional support.

- Eric Dean Rasmussen and Lisa Swanstrom

A Panoramic View

In Walden (2017), the new video game out from Tracy Fullerton and the Game Innovation Lab at U.S.C., it is surprisingly easy to kill Henry David Thoreau.💬ALENDA CHANG: I just hosted Tracy at UCSB! Technically, Thoreau doesn’t die, he just faints/passes out from exhaustion.LISA SWANSTROM: I love this—cue the music for “It’s a Small World, After All,” a tune which works here I think on multiple levels! All joking aside, Tracy Fullerton and her team have made a gorgeous game. 1 The game allows the player to explore Walden Pond and its environs through Thoreau’s perspective, by reading excerpts of his journals and using them to navigate (Fullerton). The game’s motto—“Play deliberately”—riffs on Thoreau’s words 💬ERIC DEAN RASMUSSEN: For a thorough (pardon the pun) account of Thoreau’s project of living deliberately, see Laura Dassow Walls’s Henry David Thoreau, A Life (U of Chicago P, 2017) and her ebr essay “Beyond Representation: Deliberate Reading in a Panarchic World.” LISA SWANSTROM:That’s a great resource. I would add also Kristen Case’s “Thoreau’s Radical Empiricism: The Kalendar, Pragmatism, and Science,” in Dassow Walls et al’s Thoreauvian Modernities (U of Georgia P, 2013). And, of course, your chapter in Post-Digital: Dialogues and Debates from electronic book review (Bloomsbury Academic, 2020): “Literary Ecology: From Resistance to Resilience.”ERIC DEAN RASMUSSEN:Thanks for the plug, Lisa. The ebr collective has worked hard on this two-volume collection. As a bibliophile, I’m looking forward to having a printed artefact to commemorate twenty-five years of online publishing. Your remark also provides opportunity to foreground an important subtext in my “Literary Ecology” essay: in our contemporary media ecology, traditional publishing systems have been severely degraded and the intellectual labor required for them to operate has been devalued. Efforts in the environmental humanities to educate, debate, and develop truly sustainable solutions to environmental degradation need to address ways of rebuilding robust, resilient, life-nourishing, media ecologies. .One ecosystem that urgently needs care is academic publishing, of which an integral element is the editorial infrastructure underlying the presses and journals. The repeated attempts to kill Stanford University Press are indicative of the devaluation of academic publishing within corporatized higher-ed systems. By publishing these post-review, behind-the-scenes exchanges, perhaps we can make perceptible more of the highly skilled, but invisible, intellectual labor required to publish a journal. Editors and the editorial infrastructure need not just recognition but resources and nourishment! but delivers an important lesson of its own, distinct from Thoreau’s, which is that while the experience of transcendent joy resulting from immersion in the natural world might function as a kind of spiritual sustenance, it is low on calories. In the game, if Thoreau doesn’t get enough food from his foraging efforts in the forest—or in Emerson’s pantry—he wilts like a flower and perishes.

This is amusing given Thoreau’s objective of living in harmony with the natural world. After all, in Walden, he moves to the woods to escape the distractions of human society in order “to live deliberately.” 💬ERIC DEAN RASMUSSEN: I’ll dissent slightly from the idea that Thoreau’s objective was to live in harmony with the natural world. His motive, I think, was more basic and open-ended that that. He wanted to discover what leading a simple, solitary existence in the natural world could teach him about how best to live. He “went to the woods” not only to “live deliberately” but also to “confront only the essential facts of life” and to “see if I could not learn what it had to teach” (61). As Nature’s student, he came to the classroom with expectations. His “Spartan-like” sojourn, during which he would “suck out all the marrow of life,” might be “sublime” or it might reveal life’s “genuine meanness” (61). Both possibilities suggest Thoreau realized his edifying stay at Walden might be less than harmonious..That noted, Thoreau was a keen observer of what he perceived and described as a natural harmony. Typically, this harmony is mostly imperceptible to humans. On precious and rare occasions, however, natural objects serve as mediators that enable us to perceive glimpses of these processes..Two examples:.1) In the short, penultimate paragraph that closes “Ponds,” for instance, Thoreau recounts in exquisite detail how, in June, hummingbirds visit the “blue flag (Iris versicolor) lilies growing on nearby White Pond’s “rarely… profaned” surface. The emphasis of the passage, as I read it, given how its final sentence concludes (“…and especially their reflections, are in singular harmony with the glaucous water” [134]), is on how the body of water acts as a natural medium..The section then concludes with a paragraph about our propensity as humans to be properly attuned to natural media. It begins with Thoreau likening White Pond and Walden to “great crystals” that are foolishly disregarded in favor of “precious stones” with “market value” (the metaphor is ornate and expressed in a speculative conditional sentence that imagines the ponds congealed into small stones and carried off slaves to adorn emperors’ heads) and with Thoreau lamenting that “Nature has no human inhabitant who appreciates her. The birds with their plumage and their notes are in harmony with the flowers, but what youth or maiden conspires with the luxuriant beauty of Nature?… Talk of heaven! Ye disgrace earth” (134). His admonition, ultimately, is an appeal to put aside theological speculation about another, better world and instead to observe and revere this one. Deliberate observation and daily study of the material environment is form of devotion and reverence..2) In “The Pond in Winter,” which details Thoreau’s efforts to map Walden’s depths while traversing its now icy surface, he remarks on humanity’s efforts to understand the “laws of Nature”: “Our notions of law and harmony are commonly confined to those instances which we detect; but the harmony which results from a far greater number of seemingly conflicting, but really concurring, laws, which we have not detected, is still more wonderful” (194)..There’s so much to unpack here, but what strikes me is how the affect of wonder works..A familiar complaint about modernization is our technoscientific understanding of the physical world has demystified it ways that have contributed to its devaluation and degradation. Thoreau regularly expresses similar sentiments. But here Thoreau acknowledges the limitations of empiricism while advocating for an aesthetics of wonder. This aesthetic is both scientific and artistic, indeed the two methods feed into each other..From an instrumentalist viewpoint, Thoreau’s laborious efforts “to recover the long lost bottom of Walden Pond” might seem trivial. But regardless if the data collected about the pond’s depth was of immediate scientific import, his experiments in this natural medium yielded what, philosophically speaking, I would gloss as an extended meditation on the implications, cognitive and affective, of metaphysical certainties and choosing an anti-foundationalist towards authority and first principles. For a rigorous account of how “the principle of uncertainty is built in” to Walden, see Walter Benn Michaels, “Walden’s False Bottoms” in Walden and Resistance to Civil Government (Norton, 1992)..“Often life is frittered away by detail,” Thoreau cautions (62), so I hope my unintentionally long comments on Walden here in the margins don’t seem frivolous or self-indulgent. Editing this gathering inspired me to reread different editions of Walden and listen to an audiobook version Walden repeatedly for two weeks during my daily, ninety-minute-long hike. The implication here is that the forest will somehow strip all obstacles to the exertion of his own free will, a statement that reads suspiciously when he relates his encounters with the squirrels and jays, “whose half-consumed nuts I sometimes stole,” as well as his other struggles for basic sustenance. But this passage is also ironic. We tend to think of Thoreau as hostile to mediation, especially that of the natural world (to which, for Thoreau, the mediation is always inferior), and yet here he appears as a hyper-mediated avatar💬ELIZABETH CALLAWAY: Is Thoreau hypermediated in Bolter and Grusin’s sense? Are there aspects of the game that draw attention to the fact that you are playing a game? That get in the way of immersion? The pictures provided seem like the game might draw more on immediacy and immersion given the lush, detailed renderings of trees, reeds, and sky. And how does it compare to and comment on Thoreau’s book, which, is of course a mediation of Walden pond as well. Is the game, for example, making a point of being twice-mediated—a representation of Thoreau’s representation of a pond? ZACH HORTON:Great questions! Thoreau’s text actually seems less immediate than this game—not quite remediated (though maybe a case could be made) but certainly highly abstracted (into lists and arguments and non-linear vignettes, etc.). The mediated experience of Thoreau’s text is very unlike a graphical 3D adventure, though the necessity of balancing one’s avatar’s caloric intake hints at the book’s economics.ERIC DEAN RASMUSSEN:Eating habits are understandably a major concern and component of Thoreau’s ascetic lifestyle. Even so, Zach, the number of references to eating in Walden is striking. Five that especially struck me, as I listened to Walden while walking after dinner, in part to burn-off extra calories:.1) Immediately after famously declaring, “Simply, simplify,” he clarifies: “Instead of three meals a day, if it be necessary eat but one; instead of a hundred dishes, five; and reduce other things in proportion” (62). .2) In “Economy,” when addressing his readership/ audience (first drafts were delivered as lectures), many of whom he has already identified as “poor students,” (1), Thoreau acknowledges their poverty and their experience with hunger (“I have no doubt some of you who have read this book are unable to pay for all the dinners you have eaten” [4]) before effectively thanking them for “coming to this page to spend borrowed or stolen time, robbing your creditors of an hour” (4)..3) After describing how he has largely outgrown the hunting and fishing he loved during boyhood, and his belief that abstaining from eating “animal food” enables one to “preserve” the “higher or poetic faculties,” Thoreau speculates that humanity will eventually abandon carnivore diets: “Whatever my own practice may be, I have no doubt that it is a part of the destiny of the human race, in its gradual improvement, to leave off eating animals” (144)..4) At the same time, Thoreau was not “squeamish” and “could sometimes eat a fried rat with a good relish, if it were necessary” (145). (Is this sentence not a textbook case for the importance of close or attentive reading? So much depends upon not skipping over the words “a good” that turn “relish” from a modifier into a noun.).5) Thoreau does relish, I think, describing the grossness of his frugal diet and ascetic lifestyle. They make him appreciate how older civilizations, in particular the “Hindoo lawgivers,” were not averse to and addressed openly in their holy texts what psychoanalysis calls the abject:” in an educational video game.

In a journal entry from January 1852, Thoreau writes scornfully of mediation and singles out the art form of the panorama for his particular disgruntled attention: “The World run to see the panorama when there is a panorama in the sky which few go out to see”💬ERIC DEAN RASMUSSEN:I read this not so as contempt for mediation but as an expression of bewilderment intended to provoke people who begin to allow let representations, or mediations, or simulations of the natural world become substitutes for going outdoors and experiencing that world firsthand. .You can hear reverberations of this sentiment expressed, for instance, in U2’s “Even Better Than the Real Thing,” a stadium anthem written to ironize the spectacular mass-mediated spectacle of their Zoo TV tour, though Thoreau, like other canonical Romantic writers, is better at nuanced irony and, frankly, far less annoying than Bono (who, to his credit I guess, did succeed in becoming fly-like). .But at the risk of sounding pedantic (I plan to use this article the next time I teach Walden) and stating the obvious, metaphors are never merely… window dressing for Thoreau. They are linguistic tools for translating aesthetic phenomena that he perceives via what our twenty-first century understanding of biosemiotics and neuroscience allow us to conceptualize as natural media. (201). And in an earlier passage from this same journal he uses the panorama, again, as a mere metaphor for a higher form:💬ERIC DEAN RASMUSSEN:Thoreau doesn’t deploy metaphors mindlessly, he understands, intuitively, what cognitive linguists claim: metaphors are conceptual tools for orienting our bodies in the material world. But for any readers who haven’t (yet) read much Thoreau, maybe put that “mere” in scare quotes. Spoiler alert: I love the way you track the panoramic trope in Thoreau, Lisa, and use it to set up your critically informed appreciation for the layers of mediation in both the panorama—easily neglected as an obsolete, kitschy form, and the Walden game. “I go forth each afternoon and look into the west a quarter of an hour before sunset, with fresh curiosity, to see what new picture will be painted there, what new panorama exhibited…Can Washington Street or Broadway show anything as good?” (179). At first glance, such passages seem to confirm to the stereotype we have of Thoreau:💬ERIC DEAN RASMUSSEN:Do we want to be careful not to reinforce the stereotype?LISA SWANSTROM: Ha! I don’t know. In some ways the stereotypes serves our discussion, even if it makes HDT the straw man. That is, calling attention to how the very stereotype is, itself, a highly mediated phenomenon is pretty interesting in terms of how media gets naturalized.ERIC DEAN RASMUSSEN: You’re absolutely right. One of the things I’ve really come to appreciate, immersing myself in different mediations of Walden in the past couple weeks: two printed codex books (a gorgeous, illustrated, small coffee-table sized volume on Yale University Press edited and annotated by Jeffrey S. Cramer, the curator of collections, The Thoreau Institute at Walden Woods and the second Norton Critical Edition, edited by William Rossi, that contextualizes Walden by placing it alongside “Resistance to Civil Government,” journal entries, nineteenth-century reviews, and first-rate scholarship from the 1940s to the 1990s), Project Gutenberg’s online digital eBook, and a CD audiobook from Naxos I streamed via Tidal at home and downloaded for listening while walking along the Gandsjforden..Listening to Walden really made me appreciate Thoreau’s rhetorical savvy. He regularly uses hyperbole, scolds readers, and uses a variety of techniques that are designed to make him seem, at times, like, to put it politely, an egotistical pain in the arse. I discovered that I became so engrossed by the intricacy of the images and ideas conveyed in his poetic prose, which was constantly in motion, that I was largely oblivious to the scenery around me. Only intermittently, when Thoreau would describe phenomena ostensibly occurring as he narrates, was I reminded to pay attention to the sights, sounds, and smells, around me..Barbara Johnson admiringly refers to the text’s obscurity. Her exemplary deconstructive reading draws attention to the “perverse complexity of Walden’s rhetoric,” which she claims “is intimately related to the fact that it is never possible to be sure what the rhetorical status of any given image is” (450). Finding ways to convey visually the conceptual density of Walden’s imagery must be, I would imagine, one of the biggest challenges the game designers faced when remediated it. that his work is antithetical to mediation, to technological intervention. In Walden the game, however, a gorgeously rendered and meticulously researched work of digital art, Thoreau exists as a hyper-mediated avatar, controlled by undergraduates in our library’s Digital Matters Lab.

Those who might be more comfortable playing Walden than reading it may share Thoreau’s opinion of a panorama as a substandard art form. But one hundred years ago, the panorama was no anomaly. It was a vital form of entertainment that appealed to people of all classes and cross-sections of society. And even though the panorama has all but died out as a popular art form today, it remains worthy of consideration, not only in terms of its value as a historic curiosity, a medial pre-cursor to cinema, immersive theater, virtual reality, and the like, but also as something that has participated deeply in the formation of a uniquely American set of cultural values. As Erkki Huhtamo writes in Illusions in Motion: Media Archaeology of the Moving Panorama and Related Spectacles, an analysis of these past forms “corrects our understanding … by excavating lacunas in shared knowledge. It reassesses existing media-historical narratives that are biased because of their ideological and historiographical presuppositions” (xviii).

One such “media-historical narrative” that the panorama has helped shape is the story of American expansion, colonization, and manifest destiny. This story is a familiar one. But an excavation of the panorama in terms of both its specific manifestations and the curious affective response it provokes in Thoreau complicates Thoreau’s attitude towards mediation in general and toward the panorama in particular. Such an excavation also helps us “reassess” the larger story,💬KAREN BISHOP:Lisa, can you say a bit more about this “larger story”? LISA SWANSTROM: Hrm. I suppose I mean the entire narrative of American exceptionalism. by revealing that the “historiographical presuppositions” we have about it require re-examination. What we find in such a re-consideration is that the rhetoric of American expansion is not merely one of divine right or exceptionalism, but is also intimately connected to emerging views about what will eventually constitute our conception of “Wilderness.”💬ALENDA CHANG:Here and below I wonder if it would help to acknowledge the common misreading/misquoting of “wildness” as “wilderness” in the famous section from “Walking”? LISA SWANSTROM: Yes, absolutely. Hereby acknowledged—and I am grateful for that catch. That you and Zach and Eric all mention this at various stages in the sidebar is great. I will only add to your observations that although both wildness and wilderness have a shared etymology, they fork wildly—(sorry, I couldn’t resist)—as the concept of wilderness as a legal category evolves.

In “Walking,” an essay that he started as a lecture in 1851 and continued to refine over the course of a decade, Thoreau recounts visiting two panoramas in Boston. The first is Benjamin Champney’s “The Rhine, Great Panoramic Picture of the River Rhine and Its Banks.” The second panorama is most likely Sam Stockwell’s “Colossal Moving Panorama of the Upper and Lower Mississippi Rivers” (Schneider). Thoreau writes of his encounter with Champney’s “Rhine” panorama in favorable terms: “It was like a dream of the Middle Ages.💬ELIZABETH CALLAWAY:I wonder what about this panorama made it function as a time machine in addition to a teleportation device.LISA SWANSTROM: I love thinking about the panorama as a time traveling technology. And here, it seems, both panoramas are doing this, but traveling in opposite directions—with Champney moving back in time and Stockwell’s taking us to the present. I floated down its historic stream in something more than imagination … I floated along under the spell of enchantment, as if I had been transported to an heroic age, and breathed an atmosphere of chivalry” (14). His encounter with the “Mississippi,” however, provokes an entirely different response. “Soon after” his experience with “The Rhine,” Thoreau notes,

I went to see a panorama of the Mississippi, and as I worked my way up the river in the light of to-day, and saw the steamboats wooding up, counted the rising cities, gazed on the fresh ruins of Nauvoo, beheld the Indians moving west across the stream, and, as before I had looked up the Moselle, now looked up the Ohio and the Missouri and heard the legends of Dubuque and of Wenona’s Cliff—still thinking more of the future than of the past or present—I saw that this was a Rhine stream of a different kind; that the foundations of castles were yet to be laid, and the famous bridges were yet to be thrown over the river; and I felt that this was the heroic age itself…

The contrast between the two experiences is striking. The Rhine causes him to “float,” suggesting downstream travel, positioning him as a passive, ghostly witness to the past, a spectator rather than a participant. That “it was like a dream” solidifies this passivity, as if he were sleep-floating.

The Mississippi results in an entirely different reaction. It is in flux, and Thoreau describes his exploration of it as an active pursuit: “I worked my way up the river,” he says, and this more vigorous description echoes the multifold action the that the panorama depicts—the steamboats burning wood in order to travel, the building of cities on the river’s bank. These moments energize Thoreau. His impression? that “this”—rather than the still, even decadent, beauty of a European past—is the “heroic age itself” emerges from his excitement about the as-yet unsettled future.💬KAREN BISHOP:I am wondering about this impression that he’s seeing/participating in “the heroic age.” What comes before and after this age? What does it promise, particularly about the future and man’s relation to his environment? LISA SWANSTROM:Great question. It might be too subtle, but it seems instructive to think of the contrast between Thoreau’s notion of a “heroic age” and ancient conceptions of the same as, say, in Hesiod (or Plato), in which the Age of Heroes stands apart from an otherwise degraded evolutionary line (first there was the Golden Age, and then the Silver, and then the Bronze, and finally the Iron age, with the Age of Heroes sandwiched between Iron and Bronze). In antiquity, the Age of Heroes if filled with adventure, glory, and divine bloodlines playing out on a grand scale. But it’s coming out of an already well-established narrative framework. Thoreau—here, at least—conceives of something quite different. It is the very origin of an “American” identity that excites him. Settlement rather than birthright, perhaps, inspires the comparison. ERIC DEAN RASMUSSEN: Thoreau’s notion of heroism was likely informed by reading the Scottish writer Thomas Carlyle’s 1840 collection On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History (1840). Thoreau regarded Carlyle as a literary genius and, according to Catrin Gersdorf, his figuration in “Walking” of the Walker as “a sort of fourth estate, outside of Church and State and People” (Thoreau qtd. in Gersdorf, “Political Ecology: Nature, Democracy, and American Literary Culture,” in Hubert Zapf, ed., Handbook of Ecocriticism and Cultural Ecology, De Guryter, 2016, p. 179) is an expression of the egalitarian democratic potential he perceived in the act of walking. For Thoreau, walking was both a habitual practice integral to his way of living deliberately and a public expression of freedom available to all. In this and other ways, walking for Thoreau was a mode of democratic agency analogous to rhetoric, writing, and literature. .All of these practices were more accessible than ever before in history—at least to those Americans with the liberty to roam freely, and refine their facilities with two basic natural media: their bodies and their language. This notion of a freedom to roam goes a long way to helping understand what made 19th century America a heroic age. .Does this all sound a bit grandiose? [Cues “Roam” by the B-52s.] A bit, yes, and we’re all well aware of the horrific world-historical events in the 20th century that made 19th-century beliefs in the inevitability of progress seem naïve. .Still, living in Norway and Sweden, I’ve become Thoreauvian in my love of alllemannsretten, the general public’s right to roam on most land, whether it be public or privately owned. Thinking about Gersdorf’s reading of Thoreau as “a political ecologist par excellence” (176), because of the audacity he showed in aspiring to “speak a word for Nature,” makes it easier to understand Thoreau’s love of the Wild.

These moments stand out because they contradict Thoreau’s later disapproval in his Journal regarding the mediation of natural spaces. “The Rhine” and the “Colossal Mississippi” mediate Thoreau’s experiences of “nature” and structure his subsequent conclusions. Both panoramas are lost to us today; but in the only surviving panorama of the Mississippi from this time period, by Johnathan Egan, the Mississippi unfolds as a lurid panoply of wonders. Rainbows, sunsets, caverns, and scenes of Native American tranquility are only occasionally disrupted by moments of conflict.2 Such panoramas💬ALENDA CHANG:A useful source might be Brooke Belisle’s essay “Nature at a glance: Immersive maps from panoramic to digital” that compares 19th and early 20th century panoramas to contemporary ones. depend upon picturesque, romantic notions of landscape, with the river providing a narrative arc that functions to locate the audience both geographically (The Ohio, the castles dotting the bank of the Rhine) and temporally (downstream, to the past; upstream, to an as-yet unsettled future).

Although he expresses later disapproval of the panorama as a visual/aesthetic? form, his encounters with them here, in “Walking,” indicate that, rather than failing mimetically to capture the full totality of nature, i.e., the supreme “panorama in the sky,” they have in fact helped to train his eye and structure his sensibility of the American West.💬ERIC DEAN RASMUSSEN:Wonderful. I would only add that Thoreau’s attitudes about the West were, like all the other places he had not visited, shaped by a multitude of mediating forces. Thoreau contemplates “The Rhine” and “The Mississippi” in vivid and ekphrastic terms and exults in both depictions, even as he favors one over the other. These works do not merely engender rich, sensorial experiences for him. Instead, and perhaps in part because of the sensory engagement they foster, they also help shape his aesthetic theory. In the subsequent paragraphs Thoreau uses the contrast between the two panoramas to come to an important conclusion about nature:💬Karen Bishop:As well as about civilization, right?LISA SWANSTROM: I would say so. The contrast to civilization seems essential to HDT for locating nature.

The West of which I speak is but another name for the Wild…in Wildness is the preservation of the World. Every tree sends its fibers forth in search of the Wild. The cities import it at any price. Men plow and sail for it. From the forest and wilderness come the tonics and barks which brace mankind. Our ancestors were savages. The story of Romulus and Remus being suckled by a wolf is not a meaningless fable. The founders of every state which has risen to eminence have drawn their nourishment and vigor from a similar wild source. It was because the children of the Empire were not suckled by the wolf that they were conquered and displaced by the children of the northern forests who were.

The wildness of the American wilderness here is keyed to the future, towards participation, towards action, and to the industry associated with western expansion. Wilderness provides the necessary sustenance for it, in fact—the “tonics and barks”—as well as its mythological buttress, with the insertion of the story of the Italian she-wolf, that quintessential icon of Empire. As Richard J. Schneider writes in the Journal for the Thoreau Society, “The American frontier was also of interest” to Thoreau, “particularly in contrast to Europe. The idea of America’s ‘manifest destiny to march civilization all the way to the Pacific Ocean was much in the air, and in “Walking” Thoreau” aligns this movement with the “‘wildness’ that was essential to keep both individuals and nations young and healthy, both physically and spiritually” (6).

Wilderness configured💬ZACH HORTON:Here is another place we might pause and think about that distinction between wildness and wilderness. The wildness that is the lifeblood of (colonial) civilizations, as a continually renewed resource, surely cannot have definite spatial coordinates for Thoreau or it would be “left behind.” Yet the land that is wild, the wilderness, must surely be part of this problematic sustenance. Either way, the subsequent point about conservation is an interesting reversal. Wildness is not conserved through absence but renewed through presence, presumably. Then again, perhaps there are human and non-human forms of wildness, and scenes like wilderness are site of exchange…KAREN BISHOP:Yes, the panorama contributes to our/Thoreau’s understanding/construction of both.LISA SWANSTROM:I like this line of thought so much. It reminds me of a claim that Bill McKibben (and probably others) made in the 1990s, which is that wilderness is a place somehow outside of commerce—or at least a place that, when you are inside it, you cannot participate in commerce: “What sets wilderness apart in the modern day is not that it’s dangerous (it’s almost certainly safer than any town or road) or that it’s solitary (you can, so they say, be alone in a crowded room) or full of exotic animals (there are more at the zoo). It’s that five miles out in the woods you can’t buy anything” (129). Obviously, this statement no longer stands—at least if the person “in wilderness” has good cell reception, good credit, and a smartphone—but the very idea that there could be a place outside of commercial exchange remains powerful, enticing, and well, utterly fantastic. here is not at all consistent with the way we understand it today. In the American imagination, at least since the Wilderness Act of 1964, wilderness is a site of conserved land, free from human infrastructure. Its strict, legal definition is quite clear on this point: “A wilderness, in contrast with those areas where man and his own works dominate the landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain” (“Wilderness”). We tend to think of Thoreau as the original proponent of wilderness, and in an important way he is, but in the one hundred and fifty-plus years since the time of his writing, we have also tended to divorce efforts aimed at wilderness conservation from the history of colonial expansion, viewing the former as a virtuous endeavor meant to stave off the full-scale destruction of natural ecologies and the latter as the wicked cause of that same destruction in the first place. And yet, as Thoreau’s enthusiastic attitude toward Western expansion demonstrates, the two stories are interwoven. The history of American wilderness is also a history of colonial conquest and displacement.💬ERIC DEAN RASMUSSEN:Very true. But I’d also like to endorse arguments Marc Luccarelli has made about multiple conceptualizations of “wilderness” in Thoreau. Luccarelli wants to recuperate some of these so that Thoreau and the transcendentalists are not rashly discarded as retrograde utopians. See “The ‘Feral’ Wilderness: American Studies, Ecoliterature, and the Disclosures of American Space,” American Studies in Scandinavia, 41.1, 25-36, 2010.LISA SWANSTROM:This sounds great. KAREN BISHOP:and deferral?ERIC DEAN RASMUSSENAbsolutely—perhaps endless deferral? Although is deferral that is constructed to be endless really deferral?

The often-hazy connections among real-world ecologies, the artistic expressions they inspire, and the aesthetic experiences💬KAREN BISHOP:And historical also? as in historical consciousness? or would that be a detour?LISA SWANSTROM:Not at all. As problematic as he is, Nietzsche’s poetic, nearly lyric claim that “the past flows on within us in a hundred waves” is prescient in its urgent call to acknowledge the way the past keeps working in our present (22). This is a great through-line that you are weaving through the conversation, and I appreciate it. they provoke—as well as the way each participates in the formation of public consensus and shapes the historic record—is what motivates this gathering on the topic of “Natural Media.” To elaborate this concept more fully, I shall now turn to another panorama that will help clarify these relations in a more contemporary context.

”Effulgence of the North”

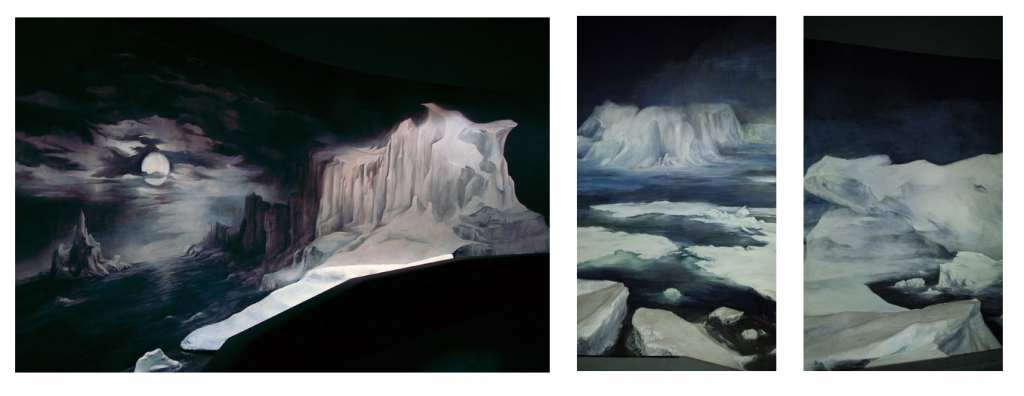

From 2010-2017, the upper level of a small, unassuming theater in central Los Angeles served as a portal to two distinct but entwined ecologies: those of nineteenth-century visual culture and the Polar Circle. The historic Union Theater, site of the Velaslavasay Panorama, hosted “Effulgence of the North,” an exquisitely painted depiction of an Arctic landscape by Sara Velas, the theater’s proprietor. Complete with ice caps, sweeping blue-green auroras, sculpted floes, and an audio track of haunting windsong, “Effulgence” was an impressively immersive 360-degree experience in the mode of a nineteenth-century panorama. It was also a novel experience. Very few panoramas from the nineteenth century exist today, and the Velaslavasay’s re-recreation is the only one in the greater Los Angeles area that I am aware of.

As we have seen, the panorama of the “Mississippi” excited Thoreau’s energies about the prospect of a shared American future. This future, however, although still unformed, was in some ways already rhetorically justified through the notion of “manifest destiny” and symbolically cemented in expressive works, such as the “Mississippi.”

Similarly, “Effulgence of the North,” with its vivid colors swirling like Auroral ribbons on a darkened sky—Elvis-on-velvet lurid—conjures and confirms many of the romantic notions we have about the “North.” In August, the weather in Los Angeles can be hot, bordering on infernal. But even though the Union Theater is over 100 years old and the Velaslavasay has no air conditioning to speak of, walking inside the darkened circle feels like stepping into a glacial rift and stepping back in time. And even as I recognize that its connection to the real Arctic, per se, is tenuous at best, in my mind, the “Effulgence” remains continuous with the real-world North.💬KAREN BISHOP:perhaps you’d like to include some of your own pictures from the Arctic, Lisa?LISA SWANSTROM:I am grinning right now—I must confess that I was *delighted* to be able to include my photos of the “maelstrom of Bodø” (see the image below, on the right!).

Much like “The Rhine” or “The Colossal Mississippi,” the Arctic is a site of symbolic import, not limited to its geo-spatial coordinates on earth. In fact, “the Arctic” as a symbolic site has evolved in the larger cultural imagination in ways that impede our understanding of the real McCoy.💬ALENDA CHANG:It might be worth bringing in Peter Krapp’s work on polar culture, particularly as a site for conspiracy theory (given Zach’s work on chemtrails). This symbolic “Arctic” landscape is figured as exotic, pure, vast, and unfathomably remote. During the height of nineteenth century exploratory frenzy, in particular, many works of literature served to amplify such attributes; in them, the Polar regions operate as places where the laws of physics are alternately exaggerated, bent, re-written, or suspended completely.💬ELIZABETH CALLAWAY:This section on the arctic reminds me of the current project of the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, located on a Norwegian island beyond the arctic circle. The seeds are kept in air-tight deep-freeze conditions in an attempt to suspend them in time and keep them from degrading. Laws of physics re-written indeed..Moreover, the Seed Vault’s location in the arctic draws upon the image of the arctic as a separate sphere, unattached to the rest of the world. On the Seed Vault’s website, the arctic location is described as safe from the natural disasters, political conflicts, and funding whims to which local seed banks are subject. The illusory nature of this separation from the troubles of the world was exposed in 2016 when melting permafrost caused the entrance to the vault to flood.LISA SWANSTROM:Your work on biodiversity has made me think of the Svalbard Seed Vault in entirely new light, and I am super excited to read your forthcoming book: Eden’s Endemics: Narratives of Biodiversity on Earth and beyond (under contract at U of VA P).

For example: In Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, the polar tundra is the backdrop upon which the Creature chases his creator and is chased by his creator in turn; the letters that Walton writes to his sister back in England serve the purpose of creating both geographic and narrative distance, and the icy region provides an apt environment for suggesting💬KAREN BISHOP:And pursuing?LISA SWANSTROM:Absolutely! And its pursuit here suggests that new knowledge depends on geographic distance, which is fascinating. the limits of human knowledge.

In Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” the landscape of the Polar South takes on a supernatural beauty, complete with striking contrasts between darkness and light, a place which both provokes an evil act and offers an opportunity to atone for it. This beauty is embodied in the fantastic “water-snakes” the Mariner espies: “They moved in tracks of shining white…Blue, glossy green, and velvet black / They coiled and swam; and every track / Was a flash of golden fire” (lines 272-281). This moment—in which the Mariner holds in awe the arresting beauty of the sea snakes, whose curving motion, all “glossy green” and “velvet black,” echoes the celestial power of the Aurora Australis—is the cause for his redemption. But the entire region is also a hot-spot for a variety of supernatural forces: Spirits and ghosts move in and out of bodies here with the ease of the holograms who fly about Disney’s Haunted Mansion.

In Edgar Allan Poe’s “Descent into a Maelstrom,” which takes place at Bodø, the gateway to the Lofoten Islands of Arctic Norway, the whirlpool takes on monstrous proportions. Arthur Rackham’s nineteenth-century illustration makes the most of this dramatic vortex, highlighting the deep hole that sucks everything into is greedy maw. A more contemporary photo of that terrifying display of Arctic alterity, when placed next to Rakham’s illustration, is instructive.

Such stories make sense in the context of the excitement and frenzy surrounding Polar expeditions of the time; the news coverage of such journeys was sensational and steeped in adventure. It is therefore not surprising to see works of art and literature respond in kind to that tantalizing, remote exoticism.

The real-world North in the twenty-first century, however, has become a bellwether for climate change. Melting polar caps, global warming, and declining snow packs may seem like fairly recent phenomena, but human activity, particularly from the “Global North,” has been shaping the Arctic for centuries. A peculiar event from a travel expedition to the North Pole provides an instance of how the real-world North and its symbolic counterpart collide.

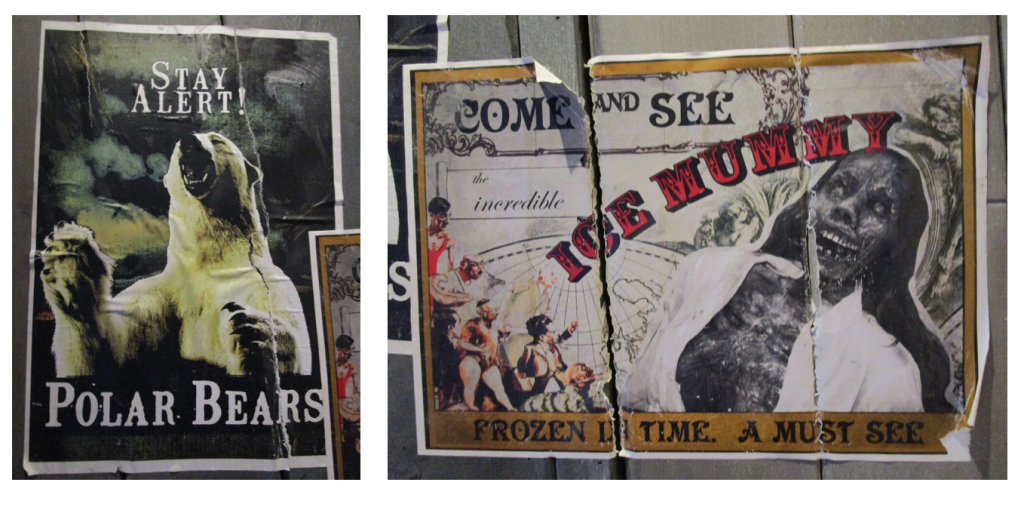

The Fram Museum in Oslo, Norway, takes its name from the ship it has preserved and now showcases. The Fram, which means “Forward”💬ALENDA CHANG:This reminds me of “slow TV” and Norway’s experiment in livestreaming the Saltstraumen:https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/apr/15/live-streaming-norway-to-show-soothing-sea-tides-on-tvLISA SWANSTROM:This is so great.ERIC DEAN RASMUSSEN:Perhaps the mediated experience of the natural world on the tube needs to be slow, because when Norwegians go ut på tur many of them hit those mountains at what many non-natives will register as breakneck speed. Lisa, you can attest to that, having been with me, near the very back of the pack during the 2018 7-Nutsturen Sandnes expedition..I won’t try to develop this theoretical speculation. Yes, it mostly an excuse humble-brag about finishing the seven peaks hike, which many participants approached as a race. [Feel free to insert image of our cool lapel pins, Lisa.] LISA SWANSTROM: Dear God. That was one of those hikes where I’m still not entirely convinced we did not die. For those unfamiliar with it, the 7-nutsturen is a 17 km. loop that hits seven mountain peaks along the way. While you can do the hike any time on your own, Eric and I did it as a part of an organized national “race.”.Two surreal moments stand out from that day that speak to the point Eric makes about slowness: 1. On the first or second peak, a full orchestra was set up and was playing music as we hiked past. Time seemed to stretch. 2.For pretty much the first half of the hike, we felt the rush of energy of thousands of fit Norwegians gambolling up rocks (and past us) like mountain goats. It was only after they’d all past us that the hike began to feel remotely “natural.” (But that was perhaps because by that point I was delirious). in Norwegian, was the craft that Fridtjof Nansen designed and took on his trip to the Polar Circle, in an expedition that lasted three years (1893-1896). The ship returned unscathed from the journey and is beautifully maintained and meticulously documented in the museum, which is itself almost panoramic. The walls surrounding the boat are filled with sculpted igloos; dining nooks with animated auroras in their windows line its walls; and an “Adventure” side quest, comprised of polar bears, howling wind, an “ice mummy,” and the mannequin corpses of unfortunate sailors, offers a break from the more staid experience of museum placards.

Nansen, a humanitarian, scientist, and champion skier, was unusual in terms of the larger frenzy to explore the Arctic.3 Certainly, he was interested in exploration, but Nansen’s primary interest was research, and his principle innovation was the construction of a ship that was built to freeze and drift with the ice. In these he was successful. Half of the three years of the expedition—eighteen months—was spent adrift, ice-locked, in the Arctic Sea, providing Nansen and the crew of the Fram ample opportunity for documenting, gathering data, geologic sampling, skiing across glacial fields, and refining navigation techniques.

An incident that Nansen reports three months into the expedition in his journal—dated Oct. 2, 1893—is striking for the way that it undermines the notion of the north as somehow removed from human influence. In this entry, Nansen describes an encounter that he and his crew have with a Polar bear: “A thin male bear…I went close up to him and thought it safest to shoot as I was not certain whether it would run off…It stood now calmly and looked stiffly at me…I gave it a bullet in the neck behind the head. It sank down just like folding up a chapeau claque.” When Nansen approaches the dead bear, he comments on the serenity of the scene: “now everything was still. A wonderfully beautiful yellow/white bear, how lovely it looked lying there silky yellow in the snow.” The moment is a beautiful one for Nansen; in it, the unfamiliar and the threatening are decisively dispatched, and the ferocity of the landscape is restored to stillness.

Similarly, the stillness of death transposes the bear; it becomes “wonderfully beautiful” and “lovely.” As it collapses, its “stiff,” threatening posture softens into something pliable and luxurious: a “silky yellow” figure in the snow. In death, the bear folds into itself like a “chapeau claque,” a collapsible top hat. This image of a formal top hat in the Arctic Circle strikes one as ridiculous, perhaps, but a signed picture of Nansen in the Fram Museum Gift Shop demonstrates that this was more common than a contemporary reader might think. In it, Nansen skis uphill, at an angle of 30 degrees, in full gentlemanly attire, complete with coat and tie and matching top hat—perhaps not a “chapeau claque,” but an important component in an elegant costume that refuses to be inhibited by inclement weather. With this simile, Nansen tailors the bear in nineteenth-century attire and situates it within the larger context of “civilization.”

Part of the power of this scene comes from that fact that it is a journal entry and, ostensibly, describes an event that really happened. Even more powerful, however, is the fact that although the entire landscape is inhospitable, threatening, and seemingly unfit for human life—indeed, the bear does not? even recognize them as human; before killing it, Nansen notes that “the bear caught sight of me, stopped and wondered what kind of a figure is this”—they manage to assert their mastery over it. The story is, at least in the encapsulated form of a journal entry, one of “first contact” between them and the region’s unfortunate ursine inhabitant. The two species—human and bear—could not be further apart from the perspective of the crew, and the exotic animal is marveled at once it is dispatched. When they butcher the animal, however, Nansen makes note of a surprising discovery: “When it was opened, the only thing in its stomach was a piece of paper where there was written: Lutten & Mohn. Packaging for a skylight which was used as toilet paper. An exquisite diet” (Nansen).

In the age of Moby Dick, the Voyage of the Beagle, and the poisonous Polaris Expedition, it is not surprising that Nansen kills the bear.💬KAREN BISHOP:Even though it was about to turn and walk away…It kills me… The desire to explore, gather data, conquer, and codify is coupled with the colonizing impulse of mastery and dominance and appears frequently in many such narratives.💬KAREN BISHOP:Right. But how interesting that Nansen should lend his name to the Nansen passport, right? So he becomes representative of the stateless, of statelessness, of the limits of human conquest and conquest of the human, etc.LISA SWANSTROM: This is a great comment—and one that speaks so well to your research on human rights, exile, and displacements of all kinds (see The Space of Disappearance: A Narrative Commons in the Ruins of Argentine State Terror <https://www.sunypress.edu/p-6881-the-space-of-disappearance.aspx>, SUNY P. 2020). I hadn’t connected Nansen-the-Explorer to Nansen-the-Humanitarian in this way, even with the Google sketch highlighting the Nansen passport. The images/personae are difficult for me to reconcile. What startles is the presence of human trash,💬ZACH HORTON:I love this weird detail.LISA SWANSTROM: Me too—I shivered when I read it. itself used to wipe away human waste, in the bear’s stomach.💬KAREN BISHOP:I wonder if there is another connection to be made here to the earlier discussion of wild/wilderness (and civilization)?.LISA SWANSTROM:I will need to keep thinking about this—but yes, I think. We might think of the polar bear’s wild status, and the wilderness it inhabits, as doubly sullied or profaned here. But perhaps especially interesting in terms of “wild” is how we think of “waste” as a concept—something both natural and abject. I’ve been working on an entirely different project about plastic and pollution, and I’ve learned so much about how “waste” as a category varies so widely.

Visceral Media

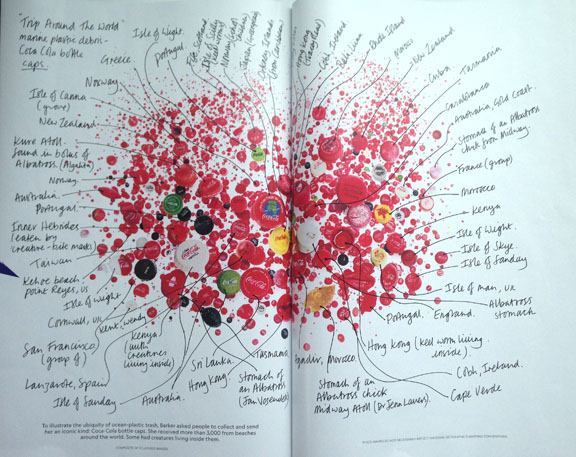

💬ERIC DEAN RASMUSSEN:We might emphasize that “visceral” is not being used exclusively in the colloquial sense (e.g., “gut feelings”), especially if these expressions are understood to be somehow non-cognitive or even anti-intellectual..Thinking ecologically, the modifier visceral suggests a relation the visceral nervous system. And ecologists, neuroscientists, etc. direct attention to the way that we feel and experience emotions throughout the body due, in part, to peptides, “biochemical manifestations of emotions” (Capra 284), which work to mediate our emotional state. These biochemical communications are best understood as being integral to cognitive processes occurring primarily in the brain and limbic system, but our perceptions and thoughts are colored by visceral emotional responses. I’m cribbing here from notes I’ve taken on Fritjof Capra’s The Web of Life: A New Scientific Understanding of Living Systems (Anchor Books, 1997), so the science is not necessarily current..The body is a highly complex communicative medium. And as we learn about the functioning of the nervous system, the more important it becomes for artists to create projects that not only stimulate the nervous system but do so in ways that make us aware of the thinking body.LISA SWANSTROM:Yes, yes, yes. I think you’ve put it exactly right—here and earlier. The power of aesthetics is tied to the power to feel. In fact, etymologically at least, focusing on the connection between aesthetics and sensation—or emotion, or affect—is almost redundant, but entirely necessary because that past meaning of the word has been obscured over time. I think your work on affect in literary ecologies might help to clarify this in eco-critical contexts. The June 2018 issue of National Geographic focuses on plastic pollution, especially as it encroaches upon marine habitat. The issue is important for its attempt to highlight ways that innovation💬ERIC DEAN RASMUSSEN:Do we want to decouple technological innovation and aesthetic expression? If so, I think we should quickly make the ecocritical point that they cannot and should not be. I also think there is a need to reconceptualize “innovation” (a buzzword that is omnipresent in neoliberal rhetoric).LISA SWANSTROM:This is a great point.ERIC DEAN RASMUSSEN: As the first editor of the ELMCIP (Electronic Literature as a Model of Creativity and Innovation in Practice) Electronic Literature Knowledge Base, I should add that digital literary practice provides examples of non-instrumentalized technological innovation and aesthetic expression might help ameliorate this problem. The entrepreneur Arthur Huang, for example, has constructed a solar-powered device, the “Trashpresso,” that compresses plastic into building tiles (Nunez 24). And in her artistic practice, Mandy Barker collects bits of plastic from beaches and oceans and photographs them against a blank drop-back. To create her “Trip Around the World” project, Barker solicited garbage from all parts of the globe, but not just any garbage: she asked for Coca-Cola bottle caps, found and extracted from litter, and arranged them in a bright display. Of the caps featured, four were found in the stomachs of albatrosses (76-77).

This is a laudable project, but Barker’s work succeeds, perhaps too well, in aestheticizing waste.💬ERIC DEAN RASMUSSEN:I want to proceed carefully on this issue. On the one hand, we want to be critically aware of the how art projects risk making dire, even catastrophic, ecological conditions too neat, orderly, even “beautiful” – a common-sense notion of aestheticization.. At the same time, we do want to make a case for what aesthetics can do – developing the creative making notion..Consciousness raising (raising awareness, drawing attention to problems, etc.) is certainly one role of the aesthetic. We need to push ourselves to make cases, I think, for others. The symmetrical display of bottle caps is removed from the grisly visual context of wide-scale animal demise. And although they are beautiful compositions of bright bits of waste, they obscure rather than call attention to the problem.💬KAREN BISHOP:Totally; she doesn’t talk about this risk at all? LISA SWANSTROM: Not in my reading of the piece. But to be fair, National Geographic isn’t exactly hard-hitting in terms of artistic/aesthetic critique. National Geographic tends to shy away from more shocking work,💬KAREN BISHOP:Is there another way to put this? Would provocative or controversial work better?LISA SWANSTROM:Very possibly, but since we’re talking about aesthetic responses here, I like that all of these words are coming up. I think such works (by Barker, to a certain extent, and definitely by Jordan, a bit further down) prompt a spectrum of unsettling emotional reactions. but it is perhaps to this type of art that we need to turn to dispel the romantic notion we have about such isolated spaces. Chris Jordan’s “Midway Project” fits this category.💬ALENDA CHANG:I haven’t had a chance to read it yet, but I’ve seen presentations from my colleague Amy Propen; her book Visualizing Posthuman Conservation in the Age of the Anthropecene includes a discussion of the Jordan project. LISA SWANSTROM: Thanks for this—it looks great. Jordan’s process is less an act of re-purposing than of ruthless observation:💬ERIC DEAN RASMUSSEN:Is it ruthless? Unflinching, maybe?LISA SWANSTROM: Unflinching also works. I want to leave both here for the same reason I mention to Karen above. But I’ll say a little bit more here. Ruthless seems extreme, I grant you, but the reaction comes not from looking at this sole image but from looking at picture after picture after picture. So the work is unflinching, but it is also ruthless and unyielding. It never softens. And clearly I’m talking about my own affective responses here. It is so hard to gauge outside of my own reactions.”On Midway Atoll,” he writes, “a remote cluster of islands more than 2000 miles from the nearest continent, the detritus of our mass consumption surfaces in an astonishing place: inside the stomachs of thousands of dead baby albatrosses…The nesting chicks are fed lethal quantities of plastic by their parents,” he notes, “who mistake the floating trash for food as they forage over the vast polluted Pacific Ocean.” Jordan’s photographs of the dead birds are beautifully composed, respectful, and horrifying.

Plastic. Bright bits of it, slender threads of it, spooling filaments, discarded refuse—this is the culprit, as well as we who make it, make use of it, consume it, and discard it. “For me,” Jordan writes, “kneeling over their carcasses is like looking into a macabre mirror…Like the albatross, we first-world humans find ourselves lacking the ability to discern anymore what is nourishing from what is toxic to our lives and our spirits” (Jordan). And, in case the albatross’ specific symbolic status is lost on the reader, Jordan reminds us of it: “Choked to death on our waste, the mythical albatross calls upon us to recognize that our greatest challenge lies not out there, but in here” (Jordan). In Coleridge’s famous “Rime,” perhaps the strongest source of the seabird’s “mythical” status, the Mariner narrates his transgression to the wedding guest, confessing that the source of his curse stems from his unprovoked killing of the sacred albatross:

And I had done a hellish thing, And it would work ‘em woe: For all averred, I had killed the bird That made the breeze to blow. (lines 91-94)

But the albatross is not just a bird in the poem. Before the Mariner’s transgression, the (capital-A) Albatross cuts through the ominous weather and functions as a divine emissary:

At length did cross an Albatross Through the fog it came; As if it had been a Christian soul, We hailed it in God’s name. (lines 63-66)

No surprise, then, that the consequence of shooting the bird is divine in scale: haunting, dehydration, and ghoulish dice rolls for the Mariner’s soul are mere preludes to his final curse,💬ERIC DEAN RASMUSSEN:The Mariner hails the Albatross in the way Coleridge’s poem and Jordan’s photos hail readers and viewers.LISA SWANSTROM: Very nice. which is to roam the earth in search of men who will learn from his mistake.

In contrast, the polar bear that Nansen dispatches is just a polar bear, one that has swallowed an advertisement used as human toilet paper that he and his crew have discarded.💬ELIZABETH CALLAWAY:It’s interesting to think of this bear in comparison to the polar bear tropes that have become prevalent in a warming climate. We’re all probably familiar with the pictures of polar bears invading garbage dumps to eat human detritus. And this bear’s nearly empty stomach filled only with a scrap of human trash prefigures the starving polar bear motif that sometimes serves as shorthand for climate change. I can’t help but thinking of this toilet-paper-advertisement-meal in light of your earlier analysis of USC’s Walden game. While consuming an advertisement is “an exquisite diet” full of meaning, it is light on calories.LISA SWANSTROM: Yes! And this is such a great example of how what seems like a very contemporary trope has a complex history, one that has evolved into a vexing mess of contradictory, present-day associations. On the one hand, Coca-cola commercials feature Polar bears as the magical inhabitants of the pristine north. On the other, as we see in the image from the above Barker piece, Coca-cola bottle caps litter global shorelines and can be found in the bellies of dead birds. The gap between the marketing campaign and the reality is as vast as it is distressing. I highlight this moment to demonstrate the insight, most recently and succinctly articulated by Heather Itzla, that “there is no away.” As Itzla writes on her blog of the same name, “Sometimes I’m nostalgic for the time before I looked behind the “away” curtain, as in “Throw it away” (http://thereisnoaway.net/). Itzla’s focus on plastic, while not identical to the problem I am tracing here, is symptomatic of it all the same. The “‘away’ curtain” is merely one manifestation of the way symbolic value can disguise or distort reality. In the case of plastic, however, this has less to do with our cultural fantasies about the Polar regions than it does with our even more pernicious attitudes towards trash.

The desire to outsource our refuse is baked in to our most foundational visions of Utopia.💬ERIC DEAN RASMUSSEN:The fantasy or myth of externality supports most colonialist rhetoric — there’s always an environment elsewhere, an outside where resources, ‘natural’ and ‘human,’ can be extracted, exploited, and used up. .One way of evaluating visceral media art projects is to assess the degree to which they short-circuit the ideological fantasy.LISA SWANSTROM: Fantastic—I like this as a heuristic. In Thomas More’s opus, it is the slaves who are responsible for attending to trash, which they are required do outside of the city limits: “without their towns,” More notes, there are “places appointed…for killing their beasts and for washing away their filth, which is done by their slaves…nor do they suffer anything that is foul or unclean to be brought within their towns, lest the air should be infected by ill-smells, which might prejudice their health” (More).4 We see this blueprint for waste management still operating today, when we look at certain meat processing plants which are adjacent to landfills or to prisons, which are disproportionately proximate to the poor, the immigrant, the disenfranchised.

The reality of global waste conflicts with our image of the North as a series of untouchable, preternatural ice castles, as they appear in texts as varied as Hans Christian Andersen’s Snow Queen and DC Comics’Superman. Such a reality collides with our conception of the Polar regions as immune to change and outside of time,💬KAREN BISHOP:Temporal considerations, history, historical consciousness(es) appear compellingly in various places throughout this introduction, but without really any pointed extended commentary. Do time and history work in explicit ways? As agents that both work upon and are themselves mediated by natural media? LISA SWANSTROM:You’ve put it beautifully. Yes, I think they do. But I’m hesitant to put it in terms of a progressive chronology, which I think I would need to do to in order to do the topic justice. The question of time, history, and the agency of both—it’s so important, but it’s larger than I’m ready to tackle. nearly alien in their hostility, an attitude that is literalized in both Christian Nybye’s and John Carpenter’s cinematic versions of The Thing as well as in The Blob, in which the Arctic serves as sepulcher for the titular character. As Kathryn Schulz writes in “Literature’s Arctic Obsession,” a perceptive analysis of polar regions, “[a]lmost invariably, the poles appear in these works as the place where nature reveals its horrifying indifference to humanity” (Schulz).

That indifference might seem unidirectional, but as more trash intrudes into Arctic waters, it is getting harder to maintain the fiction—evocative though it may be—that the Arctic regions are beyond human influence. The Poles do not represent transcendent portals, except when they appear as such in fiction, as they do in Margaret Cavendish’s Blazing World (1666).5 They might be far from us, but we must now confront the fact that we are not far from them.💬DIANA LEONG:I appreciate how deftly this section identifies the links between aesthetic and spatial distance.KAREN BISHOP:YesLISA SWANSTROM:Thanks, people. It was challenging—there’s a lot of compression. The evidence of the extent of our effect could not be more literally visceral.

Natural Media

💬ERIC DEAN RASMUSSEN:Do you think this section, or at least, the introduction of the concept of natural could/should come earlier?LISA SWANSTROM: I think you’re right. I’m going to include it as the abstract (mini-abstract) at the very beginning of the piece and leave it here, as well, along with this note. This collection emerges from a panel hosted by the MLA’s MS Forum on Visual Media (http://naturalmedia.org/titles/) in 2017. But both that panel and this gathering stem from a larger concern, which is the frustrating tendency in media studies to exclude the natural world from its purview. This is not to say that media theorists are not interested in the larger environment within which media operate, but while the term “media ecology” suggests a more inclusive approach to media studies than the merely technological, the “ecology” in question has not, until recently, tended to include features of the natural environment in its account. This is, fortunately and rapidly, changing. Books such as John Durham Peters’s The Marvelous Clouds (Chicago), Jussi Parikka’s Geology of Media (Minnesota), and Tung Hui Hu’s Prehistory of the Cloud (MIT) reveal a new interest in the capacity of natural ecologies to signify and encourage us to see continuity between natural and technological environments.💬ERIC DEAN RASMUSSEN:In August, I finally, albeit only briefly, got hold of The Marvelous Clouds. Reading it along with N. Katherine Hayles’s Unthought: The Power of the Cognitive Unconscious and Steven Shavio’s Discognition makes me think we’re likely at the beginning of a genuine paradigm shift/epistemic shift arising from an expanded sense of communication. Hayles writes about the possibilities of moving from bio-semiotics to cyber-semiotics, so the challenge is to consider at how communication and types of distributed cognition occur in natural ecosystems and artificial (AI) systems that are sentient creatures in their own right. This is exciting but also, speaking as a human, both humbling and somewhat terrifying..Hayles’s most radical claim is that these systems aren’t just communicating (as a biologist would say cells do) but thinking. LISA SWANSTROM: Paradigm shift sounds right, but I would say it’s still slow going—unevenly adopted or, like William Gibson says of the future, “unevenly distributed.” I appreciate Durham Peters’s book, but in that it purposefully eschews any form of digital communication, it seems at times to re-inscribe these tired divisions. As Peters notes in The Marvelous Clouds, “The old idea that media are environments can be flipped; environments are also media” (3). And as Alenda Chang writes in “Environmental Remediation,” an essay in a previous ebr gathering on the topic of “Digital and Natural Media,” “environments are also media, able to transmit, conceal, and come between other entities in significant ways; so too, our usual media are environments, which inevitably frame our understanding of the natural world and thus have the capacity to remediate beyond their representational margins” (Chang, electronic book review).

“Natural media” re-valuates the communicative potential of natural spaces, especially in instances where symbolic import collides with raw matter in a manner that hides from, disguises, or elides stark reality. This is not to say that such spaces cannot communicate of, to, and for themselves. Insights from ecofeminist theory, Object Oriented Ontology, Actor Network Theory, and the biological sciences attest to this activity and help us frame just how intricate and extensive such communication systems can be. See, for example, Suzanne Simard’s work on the mycorrhizal networks of Douglas fir trees in the Pacific Northwest; Richard Powers’s fictional exploration of such forests in The Overstory; and, in ebr, Melanie Doherty’s analysis of Jamie Skye Bianco’s #clusterMuck performances as “something that quite literally gets to the noisy material processes of both human and geological writing” (Doherty, electronic book review); or Dale Enggass’ reading of Moby-Dick as a novel that “not only anticipates some of the “new materialist” theories inspired by Deleuze and Guattari’s work, but also reveals how these theories fall short of their posthumanist mark” (Enggass, electronic book review).

But natural spaces and objects have also functioned historically as sites legible to humankind, as well as surfaces upon which humankind inscribes its values. These sites operate on every conceivable level: practical, in terms of weather patterns and sustenance; religious, in terms of omens and augury; and legal, from the mundane, run-of-the-mill decisions about the adjudications of resource management, to the weirdness of the animal trials of the fifteenth century to the “Guano Islands Act of 1856,” in which bird excrement functions as index to colonization (“Guano”).6

One could go on. In the context of this introduction, it is clear one has. In the preceding passages I have touched upon a variety of media forms, places, temporalities, and circumstances. This has involved a considerable amount of chronological and cultural compression, admittedly at the expense of a more fully articulated historic context. Yet its capacious scope is purposeful. By tracing an associative chain from a video game to Thoreau to the panoramas of the 18th century to a 21st century panoramic facsimile in South-Central Los Angeles to Romantic poetry to the Arctic Circle to the belly of a bear and the guts of an albatross, I hope it serves as an illustration of the peculiar connectedness of things. I do not mean for this statement to be taken as at all consistent with the a-historic, transcendent, and “woo-woo” manner of some very sincere environmentalists who invoke and advocate a holism that is as lovely sounding as it is vaguely delineated. Rather, I mean a connectedness that is clearly explicated and documented, historically pervasive, attendant to matter, to material history, to aesthetic expression and reception, and responsive to the forces of nature that are the very ground of our collective experience. The essays collected here are quite distinct in terms of their specific interventions, but they all explore intersections, collisions, tensions, opportunities, and affordances that arise in the discussion of “Natural Media,” both broadly conceived and in their contributors’ particular areas of research:

In “Beyond Ecological Crisis: Niklas Luhmann’s Theory of Social Systems,” Hannes Bergthaller uses Luhmann’s concept of systems to intervene in discussions about environment and ecology. “Niklas Luhmann,” he writes, “made no significant contribution to environmentalist thought.”💬ERIC DEAN RASMUSSEN: Bergthaller’s essay is especially lucid in its explication of Luhmann’s systems/environment distinction and can assist ecological thinking by depersonalizing concepts like “society” in ways that are radically counter-intuitive—e.g. focusing on communications and media—and seem anti-humanist but effectively help to counter anthropomorphism. At the same time, however, “[h]e was one of the most radically ecological thinkers of the 20th century.” Berthaller teases out the contradictions of these two statements in order to demonstrate how Luhmann’s theory of social systems “allows one to question environmentalist common sense, to disarticulate our conceptions of ecology and environment from each other, and to formulate a perspective which takes ecological concerns seriously while at the same time enabling one to understand the peculiar mixture of successes and failures, as well as the processes of institutional and conceptual fraying, which have characterized the trajectory of environmental movements since their meteoric rise in the 1960s and 1970s.”

In “The Kairotic Space of Memory: The Tejas Verdes Torture Center Repurposed in the Natural World,” Karen Elizabeth Bishop discusses the potential rehabilitation of the natural spaces that housed concentration camps during Chile’s last dictatorship (the Pinochet dictatorship), in order to examine “how clandestine detention and torture centers are reintegrated into postdictatorship societies often becomes a matter of public debate playing out in the press, in calls for proposals for what to do with the sites, and in architectural competitions.” Bishop examines “Amphibia,” “the 2012 proposal submitted by the French-Chilean architectural group AGC Concept Architectes to repurpose the space of the former prison camp Tejas Verdes, located on the coast of Chile. AGC proposed constructing a dynamic, hybrid transitional space between the urban and the biological that would both serve the depressed local population economically and provide a space for repose and reflection on the crimes against humanity committed at the site.” Bishop focuses on how “Amphibia’s engagement with the natural world provides for a kairotic space of memory, a form of memory premised on an opportune moment of learning and recognition. Kairos allows the repurposed space and the memory of the disappeared to operate in new temporal registers that provide for a new kind of political and historical engagement💬ERIC DEAN RASMUSSEN:Does the site function as a kind of palimpsest? The project of repurposing a space formerly occupied for horrific military-industrial complexes reminds me of Don DeLillo’s Underworld, specifically, the scenes where Nick Shay visits landscape artist Klara Sax’s site-specific installation of abandoned B-52 bombers in the Arizona desert. What DeLillo’s novel makes apparent is how such sites allow for an altered experience of time in which events of different durations can coincide meaningfully. For DeLillo, those meanings emerge when observant characters, and observant readers, start to perceive surprising connections between objects and events and various scales. bound up in the incompleteness of the natural world.” She argues that “This organic incompleteness is critical to how we conceive of rebuilding memory sites and collective memory.”

Elizabeth Callaway’s review of Astrid Bracke’s Climate Crisis and the 21st Century British Novel observes that this book is not really about climate at all. The book’s attention to wild spaces, however, which it conflates with climate change, serves to underscore the challenges of representing it in the first place. “Whether or not novels (and games and poems and movies etc) address climate change at all,” she writes, “they are still archives of climate crisis and can be read that way.” Even in moments which are not about climate at all, “Bracke focuses … on spatial cues and food… She hones in on settings and map directions to describe how these place descriptions function as “emotional geographies,” rather than as objective coordinate spaces.”

Building upon Bracke’s analysis of Zadie Smith’s NW, Callaway demonstrates how, in spite of its seeming lack of attention, climate change is happening in the novels Bracke examines, even if it’s not apparent from Bracke’s analysis of them. Furthermore, by calling attention to “small sentences” and passing moments that obliquely refer to climate, Callaway shows how they might work as representational strategies for mediating climate.

In “Between Plants and Polygons,” Alenda Chang💬JOSEPH TABBI:Cary Wolfe included both Peters and Chang to a gathering of his own in the first of two Bloomsbury volumes, Post-Digital: Dialogues and Debates from electronic book review.LISA SWANSTROM: Be also on the lookout for Alenda Chang’s forthcoming book, Playing Nature: Ecology in Video Games (U of MN P, 2019). explores 3D digital asset libraries for plants/trees, for cinema, games, and architectural visualization, as well as the “plant logics” used by biologists and designers to create realistic, virtual vegetation, e.g. Lindenmayer systems (L-systems). She examines “SpeedTree (winner of many sci-tech accolades from Hollywood and other industries for its use in films like Avatar and umpteen games like Dragon Age and Destiny) and XfrogPlants to discuss the codification of various industry approaches to digital plant design, as well as the rhetoric of libraries, localization, and middleware, the perceived beauty of algorithms, fractals, and generally the profits and processes of bringing computer-generated plants to life.”

In “Toward a Particulate Politics: Visibility and Scale in a Time of Slow Violence,” Zachary Horton introduces the concept of “eco-scalar breathing,” which he describes as “something like a scalar diagram of particulate technocracy,” in which “certain particulate motions (which follow successive concentration and dispersal stages) can be tracked through natural and medial registers as diverse as atmospheric conditions, conspiracy theory, and innovation discourse. Horton elaborates the concept of eco-scalar breathing through two case studies: the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster and chemtrail conspiracy media. In both the cases, particles are mobilized by forces natural and political in a scale-shifting theater of successive concentration and dispersal. Horton argues that in order to adequately track the forces that animate our mediated environment, we must practice a new form of scale-fluid witnessing, an ‘ability to follow the particles, wherever they may lead.’

In ebr’s interview with Nigel Leck, creator of the AI_AGW Twitter bot, Leck discusses the ways that automation can both resist and exacerbate skepticism about global warming.

In her review of Earth, Life, and System: Evolution of Ecology on a Gaian Planet (ed. by Bruce Clarke), Diana Leong “uses Lynn Margulis’ insights about Gaia and serial endosymbiotic theory to explore what a planetary imagination might look like when conceived with and through critical race studies in general, and black studies in particular.” Because the collection’s essays provide an overview of Margulis’ impact on the life sciences and what might be called philosophies of life, they provide Leong with an opportunity to explore how and why certain visions of life become attached to projections of the future. It is with this goal in mind that she examines how Margulis’ scholarship mediates the various scales of our ecological imaginations – from the very small (i.e., genes and microbes) to the very large (i.e., Gaia). Her work is “especially interested in how Afrofuturism can complement the techniques of speculation that [she] read[s] as necessary to Gaia theory itself.”