Attitudes of University Students Towards Digital Literature: Correlation Between Exposure and Learning

Eman Younis and Hisham Jubran's study investigates Arab university students' exposure to digital literature and their attitudes toward it. In doing so, they discover students feel the inclusion of digital literature in university-level literature courses should be a scientific necessity and that its absence in the curriculum compromises their professional development.

Background

The digital revolution has led to significant changes in the field of literature. It has influenced the text, readership, authorship and literary theory. This study examines the extent to which students of Arabic language and literature at higher education institutions in Israel are aware of these developments in the field. The study raises several main questions:

- To what extent are university students currently exposed to digital literature in their academic studies?

- What are students’ attitudes toward digital literature and its relevance to contemporary literary discourse?

- What are the potential benefits of integrating digital literature into higher education curricula?

- How might the absence of digital literature instruction affect the academic and professional competencies of literature graduates?

Before discussing the research process and its findings, a theoretical introduction is necessary. This section provides a brief overview of the major transformations in the field of literature brought about by the digital revolution. This will help the reader understand the more in-depth analysis of the research findings later on.

1. Theoretical Framework

1.1 Literature and Technology

Digital literature is defined as a work with an important literary aspect that takes advantage of the capabilities and contexts provided by the stand-alone or networked computer (Hayles, “Electronic Literature: What is it?”). The relationship between literature and technology has existed for a long time, and despite belonging to two different fields of knowledge, they have established common ground. This connection was emphasised before (Ivasheva, On the Threshold of the Twenty-First Century). The literary works from the second half of the twentieth century are characterised by a philosophical approach that was driven by a profound contemplation of a host of social and psychological challenges posed by the technological progress of the era. This technological advancement was also the main driver behind the spread and development of science fiction literature in the West. It was concluded that ongoing advances in technology will continue to shape literature: “The potential for significant developments in the remaining two decades of the twentieth century is immense. It is difficult to predict today what these discoveries will bring to the fields of literature and art.” (Ivasheva, On the Threshold of the Twenty-First Century 21).

These predictions have proven to be correct. The digital revolution has led to profound changes in all areas and introduced new values into society, culture, and history. As it ushered in a new environment for publishing, writing, and reading, literature was one of the first disciplines to be affected. Writers gradually began incorporating technological methods to present literature in new forms and with content that reflect the contemporary era and the human experience in the digital age, now known as digital literature (Hayles, “Electronic Literature: What is it?”).

As technology advanced and possibilities expanded, new digital genres emerged that were unknown in the age of print. These genres introduced a new approach to the entire literary system and changed the concepts of text, authorship, and readership. Language became only one of many means of expression. These changes required the development of critical theories and new literary concepts in order to accommodate literature in its changed form (Di Rosario; Hayles, “Electronic Literature: What is it?”; Younis, “Arabic Literature and Social Media”).

1.2 Evolution of Literary Forms Through Different Media

Arabic literature has gone through four main phases of historical development: the oral phase, the manuscript phase, the printing phase, and the digitisation phase. In each of these phases, the form and content of literature was influenced by the medium that transmitted it. For this reason, the history of Arabic Literature is taught as a compulsory subject at most higher education institutions in Israel. The aim of the course is to understand the development of literature by examining the characteristics of each phase.

In the oral phase, literature relied on the spoken language and focused on aural appeal. Writers emphasised words that were pleasing to the ear, which led to an increased use of metre, rhyme, and rhetorical devices. This was followed by the manuscript phase, in which literature moved from the spoken word to written records. Although people have been trying to develop tools for recording cultural heritage and literary works since ancient times, these early efforts were hindered by the difficulty of using these tools, so reliance on oral tradition persisted longer. When Johannes Gutenberg invented the printing press in 1483, literature experienced a revolution. This groundbreaking development enabled the mass production of books and drastically increased the number of readers. Writing, once the exclusive domain of elites and men, was made accessible to the public, leading to a wider range of literary topics and new content. Printing also revolutionised the form and structure of texts. Typography made it easier to organise and divide texts into paragraphs, introduced punctuation marks and coloured illustrations, and allowed typographers to incorporate margins and images (Martine 345).

With the burst of the technological revolution in the second half of the twentieth century, the field of literature changed fundamentally. During this phase, literature made the transition from traditional paper formats and printing presses to digital publication on sophisticated computers. This change paved the way for unimagined opportunities for creativity. Technology introduced multimedia elements into the writing process and made it possible to incorporate sound, music, images, graphics, and video. Text could now move across the screen, with dynamic use of colour and lighting, and evolved from linear, limited formats to multi-dimensional, branching structures that offered multiple pathways. Text could now be navigated horizontally, vertically or in a spiral (Hayles, Electronic Literature 43–83). These advances led to the emergence of new genres and literary forms that bear the hallmarks of the medium and the tools that created them.

1.3 Digital Literary Genres and Their Distinctive Features

The use of different technologies in literary writing and the electronic spread of literature via different platforms has led to the emergence of new genres. These genres combine technological and literary features and have given rise to forms such as generative poetry, visual digital poetry, multimedia poetry, virtual reality poetry, collaborative writing, interactive fiction, Facebook fiction, and others. Many of these genres derive their names from the techniques used to create them, and the term digital literature has become an umbrella term for all these new genres. Notably, the international organisation Electronic Literature Organization (ELO) has categorised these genres on its website according to the technologies used (ELO).

Remarkably, in just a few years, the number of digital genres has surpassed the number of traditional genres we know from print literature, illustrating the enormous possibilities that technology has unlocked. While modern debates on genre theory have focused on the intersection of genres and the interaction between different literary forms, questioning ‘pure’ genre theory, the advent of digital literature has expanded this intersection even further. Digital literature now embraces a fusion of different arts, where text can combine elements of literary writing, painting, music, and filmmaking.

1.4 Critical Theory and the Challenges of Digital Literature

As soon as digital literature emerged, hundreds of books and studies from both Eastern and Western scholars began to develop new literary theories to account for the major changes that technology brought. Discussions of digital texts, digital authors, and digital readers reveal characteristics and advantages that are different from those of traditional print. This change necessitates new forms of criticism and new terminologies.

However, a new literary criticism does not necessarily imply the abolition of everything old. It can also mean continuity and connection with the past. In other words, digital literature should not be seen as a completely independent or detached new form, separate from conventional text, but rather as a continuation and possibly evolution from traditional print works (Gourram 25). Since he first presented his arguments about hypertext, George Landow has tried to build bridges between literary texts in print and digital texts, particularly in terms of textual and narrative aspects and the role and functions of the reader.

Many Arab critics have also explored the links between critical theory and digital literature, noting that the structure of digital literature, with its adoption of multimedia and hypertext technologies, coincides with key concepts of critical theory. For example, the concept of the ‘open text’ by Umberto Eco, the ‘horizon of expectation’ by Hans Robert Jauss, the ‘implied reader’ by Wolfgang Iser, and the ‘death of the author’ by Roland Barthes, among others, all find application in digital literary forms. In addition, the use of multiple media in digital texts gives rise to multiple centres for the text, rather than a singular focal point. This is consistent with Jacques Derrida’s concept of the “decentralisation of texts” (Gourram; Nasrallah and Younis 131).

Digital literature is not incompatible with literary theory. It not only expands the concepts of literary theory, but also introduces new dimensions into it. Consider, for example, the development of the roles and functions of the reader. Traditional literary theory has dealt extensively with the reader of printed texts, developing various terms to describe their role in interpretation and meaning making. Examples include the ‘implied reader’ by Iser, the ‘super reader’ by Michael Riffaterre, the ‘informed reader’ by Stanley Fish, the ‘intended reader’ by Erwin Wolff, the ‘model reader’ by Eco, and others (see Bakhush 21).

With the advent of digital literature, however, the concept of the reader has changed, and with it the functions and forms of the reader’s engagement with the work, necessitating new terms to describe the new reader. Michael Joyce, for example, suggested dividing digital interactive texts into two categories based on the functions of the reader: ‘exploratory hypertext’ and ‘constructive hypertext’. In the first case, the reader navigates through links and explores the content without changing, deleting, or adding anything to it, whereas in the second case, the reader actively participates in the construction of the narrative by adding, changing, or deleting elements.

Markku Eskelinen has identified four types of digital readers based on their physical position in relation to the text. Alessandro Zinna, on the other hand, distinguishes between eight types of readers based on the interactive functions available to them, such as cutting, deleting, and adding to the text (see Di Rosario).

Landow uses the term ‘writer-reader’ to describe a reader who engages with a particular kind of text that requires both reading and writing. Seaman coined the term ‘view-user’ to describe a reader who interacts with texts that require viewing. Here the words are in animated form, and the text contains images that the reader should watch to make meaning.

Roberto Simanovsky uses the term ‘exterminated reader’ to describe a reader who loses control over the text. The author negates the reader’s autonomy by giving instructions that dictate the type of programme or computer the reader should use, such as a Macintosh, as in John McDaid’s novel Uncle Buddy’s Phantom Funhouse (Di Rosario 98–100).

Just as digital literature has expanded the concept of readership and added new functions to it, it has also expanded the concepts of the text and the author (Najm). It has also expanded concepts related to rhetorical devices such as intertextuality and metaphor. Scholars now speak of ‘digital rhetoric’ instead of rhetoric in its classical definition.

1.5 Digital Literature from a Pedagogical Perspective

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in integrating digital literature into educational curricula at both school and university levels. This trend reflects educators’ efforts to align literature teaching with the demands of the digital age. From a pedagogical perspective, digital literature is not merely a new form of artistic expression, but also a dynamic educational tool that fosters critical thinking, multiliteracy, technological skills, and interactive student engagement with texts across multiple modalities, including word, image, sound, and motion (Kress).

Contemporary educational research affirms that digital texts offer rich learning opportunities by promoting media and technological literacy, supporting collaborative and creative learning, and encouraging active engagement with literary texts (Unsworth; Walsh). Similarly, the OECD report underscores that interactive and technology-rich learning environments enhance student motivation and offer deeper, more relevant learning experiences. The integration of technology into education is thus considered a key avenue for developing new literacies essential for the 21st century—such as new media literacy, computer literacy, digital literacy, and multiple literacies. Kellner emphasized the importance of embedding these competencies into educational curricula, arguing that in societies where digital media play a central role in everyday life, overlooking digital literacy skills amounts to a form of educational negligence.

Within this framework, Serafini argues that reading multimodal texts enables students to develop a more nuanced understanding of contemporary narratives and engages them in critical analysis of language, imagery, and sound—thereby cultivating complex communicative and cultural awareness.

Noah Wardrip-Fruin also highlights the particular relevance of teaching digital literature today for two reasons. First, when teaching digital literature (or digital art more broadly), the computer is no longer viewed as a neutral or rigid device, but rather as a creative machine—thus demanding a new type of technological awareness, which is crucial in digital culture. Second, engaging with digital literature fosters new interpretive and cognitive skills not typically developed through reading print-based texts.

Moreover, teaching digital literature allows students to recognize the aesthetic dimensions of technology, rather than seeing it merely as a set of sterile algorithms. Reading digital literary works requires not only interpreting verbal content, but also analyzing the technological framework, as well as visual and auditory components such as colors, images, and sound effects. This calls for a distinct kind of semiotic reading—what is now often referred to as ‘digital rhetoric’ (Younis, “Rhetoric in Visual Arabic Poetry”).

Several scholars have also stressed the importance of teaching hypertext—a key form of digital literature—given its role in developing hypertextual thinking among readers, a crucial cognitive skill for navigating the web, which is itself built upon non-linear, branching structures (Hayles, How We Think; Davidson; Eshet-Alkalai).

Digital literature has, in fact, been incorporated into academic curricula in universities across the globe, either as a standalone subject or as part of broader literary courses. The book Reading Moving Letters: Digital Literature in Research and Teaching (Simanowski et al.) documents several pedagogical models. At the University of Siegen in Germany, a multimodal reading approach bridged digital and print texts, enabling students to develop a critical awareness of media forms. At Maastricht University in the Netherlands, a problem-based learning model was implemented, whereby students analyze digital texts while also producing their own creative digital works. Other experiments in the United States, Slovenia, and France emphasized multilayered textual analysis—technical, aesthetic, and contextual—alongside the use of technological tools that shape students’ understanding of reading and writing. These initiatives demonstrate that teaching digital literature is not about passive content consumption, but about reshaping the relationship between reader and text through active engagement and interpretation (Simanowski et al.). In the Arab world, there are notable examples in Morocco, United Arab Emirates and Jordan.

In Israel, awareness of the importance of integrating technology into teaching in higher education has increased significantly in recent years. The National Knowledge Center for Learning Technologies published a two-part volume featuring interdisciplinary case studies of technology integration in teaching. However, no projects were documented from the fields of language or literature, except for a single theoretical paper that addressed the topic abstractly.

While numerous studies have emphasized the importance of incorporating digital literature into education, these works primarily highlight its role in developing 21st-century competencies, as previously discussed. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is a noticeable gap in literature regarding the disciplinary dimension of teaching digital literature—that is, how the subject should be approached from the standpoint of academic specialization. This study, therefore, offers an additional contribution: besides examining students’ perspectives on the inclusion of digital literature, it also addresses the crucial question of disciplinary ownership. This focus is of particular importance, as the effective integration of digital literature into curricula depends not only on its pedagogical potential but also on clarifying who is best equipped—by training and expertise—to teach it.

An important conceptual model that has been widely referenced in educational research concerning the integration of technology into teaching is the Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) framework (Mishra & Koehler). This model identifies the intersection of three essential domains of teacher expertise: content knowledge (e.g., literary theory and evolving digital genres), pedagogical knowledge (e.g., strategies for engagement and interpretation), and technological knowledge (e.g., digital tools and platforms). Although originally developed within the context of general education, TPACK offers a valuable lens for understanding the multifaceted demands of teaching digital literature, as it underscores the importance of balancing disciplinary depth, pedagogical intent, and technological fluency.

Notably, digital literature aligns closely with the lived experience of today’s students, many of whom are immersed in digital storytelling and interactive media. Integrating such literature into academic curricula helps bridge the gap between students’ everyday digital environments and formal education. It also fosters inclusive, culturally responsive teaching that accommodates diverse learning styles and positions students as active participants in the learning process.

2. The Research

2.1 Research Methodology

The paper adopted a quantitative approach to explore the phenomenon of learning digital literature in higher education institutions. A questionnaire was developed to address the research objectives and questions.

2.2 Research Sample

A total of 230 students from eight higher education institutions (three universities and five schools for education) took part in the study. All participants were undergraduate students, 30% of whom were in their first year of study, 22% in their second year, 27% in their third year, and 20% in their fourth year. Due to the small size of the target population, it was not feasible to employ a probabilistic sampling strategy; as a result, convenience sampling was used. While convenience sampling is a non-probability method and therefore limits the generalizability of the findings, it is considered an appropriate approach in cases where the population is difficult to access or when conducting exploratory research (Etikan et al.). All participants were undergraduate students, 30% of whom were in their first year of study, 22% in their second year, 27% in their third year, and 20% in their fourth year.

2.3 Research Tools

A special questionnaire was designed, consisting of five sections and twenty-five questions. The first section contained two questions. The first was a yes-no question assessing students’ exposure to digital literature: ‘Do you know, or have you heard of digital literature?’ The second question examined the method of exposure: ‘How did you come into contact with digital literature?’ There were six possible answers for this question:

- During my academic studies

- Via the Internet

- Own reading

- Colleagues and friends

- Television programs

- Other.

The second section of the questionnaire (questions 3–10) examined the attitudes of the students who had been exposed to digital literature. The students were asked to rate eight statements on the Likert scale (six levels), where 1 means ‘I strongly disagree’ and 6 means ‘I strongly agree’:

- I have extensive knowledge of the features of digital literature.

- I am familiar with the technologies used in digital literature.

- I have only been exposed to Arabic digital literature.

- I have been exposed to the main genres of foreign digital literature.

- I have been exposed to literary theories on digital literature.

- I know some Arab writers of digital literature.

- I have read articles, studies, and critical books on digital literature.

- I know where I can find digital texts on the internet.

The third section of the questionnaire (questions 11–17) examined the depth of students’ knowledge in seven digital genres: interactive fiction, Facebook fiction, hypertext fiction, interactive poetry, visual digital poetry, video poem, and animation poetry.

The fourth section (questions 18–24) examined students’ general attitudes towards digital literature. Seven statements were measured on the Likert scale:

- Digital literature is similar, to a great extent, to printed literature.

- Digital literature does not eliminate printed literature.

- Digital literature will replace printed literature in the future.

- Knowing digital literature is a scientific necessity.

- My lack of knowledge of digital literature reduces my professionalism.

- Digital literature should be an optional course in academia.

- Digital literature should be a major subject in literature curricula.

The last part of the questionnaire consisted of a single question on digital literature and academic training: ‘Indicate the statement that most closely applies to you and your academic training.’ Five answers were suggested:

- I have studied digital literature extensively during my academic training.

- I have studied digital literature briefly during my academic training.

- I have taken a complete course on digital literature during my academic training.

- I have learned about digital literature in other literature courses.

- I have not studied digital literature at all during my academic training.

To ensure that all statements within each section were sequentially examined for their overall range, an internal consistency test known as Cronbach’s alpha was performed for the statements in the second and third sections. This test measures the scale reliability of the statements in each section, as each section focuses on a specific variable. This test was not carried out in the other sections of the questionnaire, as each section concerned different content.

The results of the internal consistency test for the second section, on access to digital literature, show that the statements in this section have a very high internal consistency (α=0.94). The third section on knowledge of digital literary genres also show a very high internal consistency for all statements (α=0.91).

2.4 Research Flow

A link to the questionnaire was distributed to the students by email and WhatsApp. It included a disclaimer that the questionnaire was confidential and that the data would only be used for research purposes. Participants took part in the questionnaire after reading the guidelines given at the beginning. A total of 338 students accessed the link to complete the questionnaire, but only 230 participants completed it. The analysis was based only on the responses of those who completed the questionnaire.

2.5 Analysis of Research Results

The sample was divided into two groups before conducting the statistical analysis. The first group consisted of students who knew or had heard of digital literature; the second group included those who had not heard of digital literature before.The results show that 53% of respondents do not know or have never heard of digital literature, while 47% know something about digital literature. Of those who have heard of or known something about digital literature, 63% have been exposed to it through their academic training, 33% through the internet, 16% through self-reading, 9% through colleagues and friends, and 3% through television programmes.

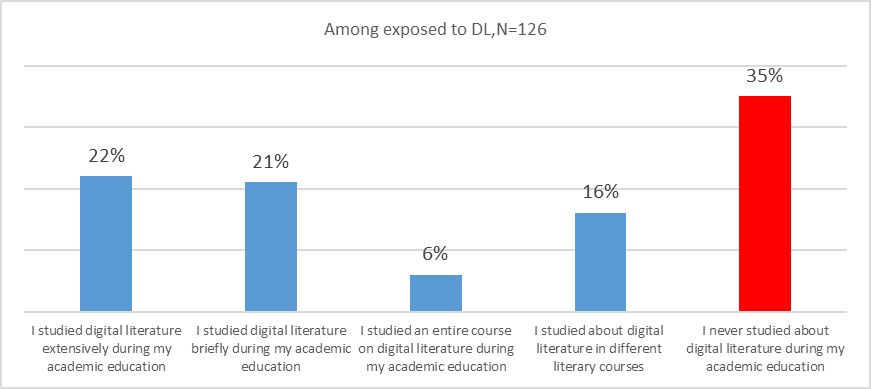

The results also show that 22% of those exposed to digital literature studied it extensively, 21% studied it briefly, only 6% completed a dedicated course in it, and 35% did not study digital literature at all during their academic training.

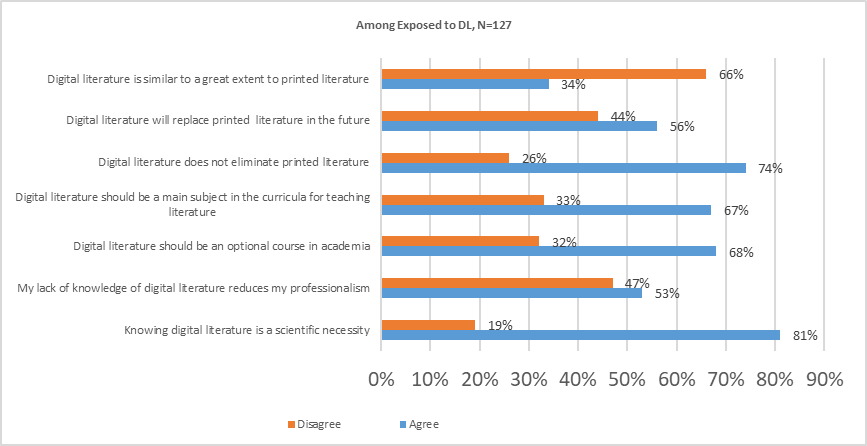

Statistical analysis also shows that 66% of those who were exposed to digital literature do not consider it similar to printed literature. However, 74% of respondents agree that digital literature will not eliminate printed literature, and 56% believe that digital literature will replace printed literature in the future.

Figure 2 shows that the vast majority (67%) of those exposed to digital literature believe that it should be included as a major subject in literature curricula, while 68% believe that it should be an optional course in academia. Overall, 81% agree with the assertion that knowing digital literature is a scientific necessity, while 53% agree with the assertion that lack of knowledge of digital literature reduces the professionalism of the learner.

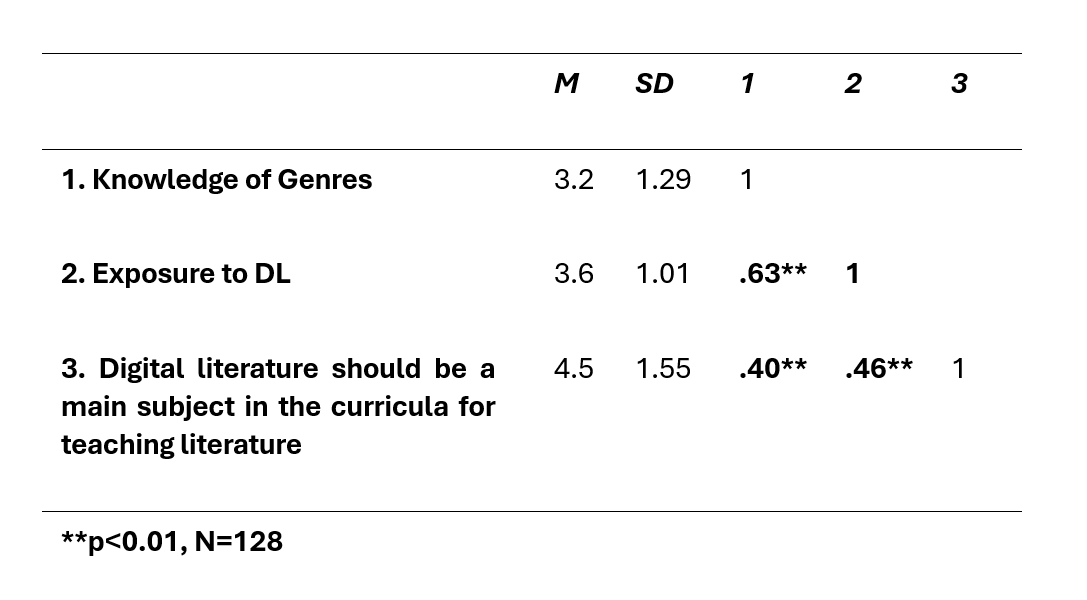

For a deeper analysis of the results, we examined the relationships between the different variables in the questionnaire. Two new variables were constructed for this purpose. The first variable, ‘exposure to digital literature’, represents the average of questions 3–10. The second variable, ‘knowledge of digital genres’, represents the average of questions 11–17. This was followed by an analysis of the statistical relationship between these two variables and the variable that measures the support of students for including digital literature in the curricula.

To assess these relationships, a statistical test was conducted to measure the Pearson correlation coefficient between the following variables: exposure to digital literature, knowledge of digital literary genres, and belief that digital literature should be a main subject in the curricula for teaching literature.

Table 1 shows a statistically proven positive relationship between the variable ‘digital literature should be a main subject in the curricula of teaching literature’ and ‘knowledge of digital literary genres’ (r = .40, P < 0.01), as well as between that first variable and the variable ‘exposure to digital literature (r = .46, P < 0.01). The more students were exposed to digital literature, the more they were likely to favour the inclusion of digital literature as a major, and the more they knew about literary genres, the greater was their support for the inclusion of digital literature as a major in the curriculum.

4. Discussion

The results show that more than half of Arab students (53%) at higher education institutions in Israel have not been exposed to digital literature at all. Among those who have, a significant majority (74%) express a positive attitude toward learning and teaching digital literature. Specifically, 67% believe it should be a compulsory subject in the curriculum, while 81% view its study as a scientific necessity. Notably, 53% believe that the absence of digital literature in their academic training negatively affects their professional competence as specialists in Arabic language and literature.

What explains these attitudes? And how does exposure—or lack thereof—to digital literature shape students’ academic development and professional readiness?

Most Arabic language and literature departments in Israeli universities offer a “History of Arabic Literature” course as a compulsory first-year subject. Logically, this course should cover the development of Arabic literature from the pre-Islamic period to the present day. However, the findings suggest otherwise. The fact that half the students had no exposure to digital literature indicates that many departments still overlook the literary transformations brought about by the digital revolution. This omission points to a broader curricular gap that disregards contemporary developments in literary production and reception.

Understanding the evolution of literature in the digital age requires more than just reading digital texts. It demands attention to the broader ecosystem of digital culture. This includes digital publishing platforms, new methods for preserving historical texts and manuscripts, large online libraries and literary websites, and the broader influence of digital humanities (Hammond, Literature in the Digital Age). Including digital literature in literary history courses helps students grasp the dynamic relationship between literature and its socio-cultural context.

While literary history courses provide a broad overview, genre-specific courses—such as those on the short story, the novel, or poetry—offer an opportunity to engage with the digital shift more directly. Just as the realist novel is taught as a product of 20th-century socio-political transformations (Barada), the interactive novel should likewise be examined as a response to technological innovation. If Naguib Mahfouz is studied as a pioneer of the Arabic realist novel, then Mohammad Sanajleh should be introduced as the pioneer of the Arabic digital novel. The same applies to poetry, where digital tools have given rise to video poetry, visual poetry, virtual reality poetry, and interactive poems—genres that reflect the evolving aesthetics of literary expression.

These changes are not lost on students. The study shows a positive correlation: the more students are exposed to digital literary genres, the more they advocate for the inclusion of digital literature in the curriculum. This indicates an intuitive understanding among students of the cultural and academic value of these texts—and of what is at stake when they are absent.

These findings also raise critical pedagogical concerns. Teaching literature requires a theoretical and analytical approach. If literary theory is taught without addressing innovations introduced by digital literature, then academic programs risk falling out of sync with contemporary discourse. This disconnect affects students’ interpretive skills and limits their ability to analyze current literary trends.

Although—as previously mentioned—prior studies have addressed the importance of digital literacy, their focus has primarily been on technical competencies. This study shifts the focus by emphasizing the need to teach digital literature as a core academic and disciplinary concern. From this perspective, the findings are troubling: more than half of students are unaware of literary forms and practices that have emerged since the early 21st century. They lack familiarity with hypertext fiction, multimedia poetry, and broader innovations in authorship and textuality. They also miss out on engaging with the aesthetic dimensions of digital creativity.

This is more than a knowledge gap; it is a structural issue that undermines both academic formation and professional preparedness. Exposure to digital literature is increasingly essential for evaluating a graduate’s readiness to engage with the evolving realities of the literary field. Without it, students are ill-equipped for roles in digital publishing, online content curation, or multimodal education. Neglecting this area risks producing graduates who lack competencies now central to professional expertise in language and literature.

Therefore, we conclude that integrating digital literature into the curriculum is both a scientific requirement and an ethical responsibility towards students. It is also a cultural imperative, given the profound shifts in literary production and reception. As Douglas Kellner argued, failing to teach digital literacy in the 21st century is a form of educational irresponsibility. Extending that logic, neglecting digital literature—which reflects key transformations in theory, authorship, and narrative form—constitutes a serious pedagogical omission. The strong support expressed by students for including digital literature in their academic training underscores the urgency of addressing this gap. What was once seen as an optional enrichment must now be regarded as an essential component of any forward-looking literary curriculum.

Despite the growing consensus on the importance of teaching digital literature in higher education, the path to implementation is not without its challenges. The first challenge lies in finding suitably qualified instructors. As previously discussed, digital literature demands both a deep understanding of its unique genres and terminology and a command of digital literacy skills. This raises a key question: who is equipped to teach the subject? A computer science instructor may possess technical expertise but lack literary background, while a literature specialist may not be familiar with the necessary tools and platforms. Some institutions have responded by pairing instructors from both disciplines—offering co-taught courses that model an effective interdisciplinary approach. Others have implemented faculty development workshops to equip literature lecturers with foundational knowledge of digital media and computing (Simanowski et al.).

A second challenge in the Israeli context is the scarcity of Hebrew-language digital literary texts, which leads instructors to rely on examples from English and other languages. Although Arabic digital literature exists, it remains limited in technological diversity, often relying on basic hypertext and multimedia techniques.

A third challenge concerns the learning environment itself. Teaching digital literature requires access to computer labs with appropriate software. Drawing on his teaching experience in Toronto and San Diego, Adam Hammond notes the value of small-group lab sessions where students can individually explore digital texts—reading, viewing, listening, and interacting—before regrouping for collective discussion and theoretical reflection (“Teaching with Literature in the Digital Age”). This blended model appears both practical and scalable, especially when students are permitted to bring their own devices into class.

As with any study, this one opens the door to further inquiry. Future research should investigate the root causes of the absence of digital literature in academic curricula. Is it due to lack of faculty training, institutional priorities, or broader policy gaps? Comparative research across languages and educational systems would also be valuable. Finally, future studies should examine the situation at the school level: what proportion of students encounter digital literature before entering university? These questions are particularly timely in light of ongoing efforts by educational authorities to introduce computer-based learning modules across subjects—efforts that reflect the increasing dominance of digital technologies in both education and culture. At the methodological level, future research with a significantly expanded sample will strengthen the generalizability of the findings and enhance the robustness of the insights. Furthermore, to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the studied phenomenon, a mixed-methods approach is recommended, combining quantitative data with qualitative insights.

5. Summary and Recommendations

Digital literature represents a significant evolution in the literary field, emerging in response to the technological revolution that has reshaped human communication and creativity. This shift has given rise to new genres, critical vocabularies, and theoretical frameworks tailored to digital textuality. As previously mentioned, excluding digital literature from university curricula risks confining literary education to outdated paradigms, thereby marginalizing contemporary forms of literary expression. The findings of this study underscore a troubling gap: nearly half of the students surveyed graduate without exposure to current research or digital literary practices.

To address this gap, the study recommends the integration of digital literature into higher education curricula through a multi-faceted approach. This includes: (1) developing specialized course modules that explore both the aesthetic and technological dimensions of digital texts; (2) offering professional development and training programs to equip faculty with the interdisciplinary skills necessary to teach digital literature; and (3) designing assessment tools that reflect the multimodal and interactive nature of digital works. Additionally, universities can take advantage of online courses offered by other institutions, particularly through distance learning platforms. Israeli universities, for instance, could encourage students to enrol in such courses to broaden their exposure to global developments in digital literature. These practical steps would not only modernize literary education but also better prepare students for the realities of contemporary literary culture.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere thanks to the Research Center of Arab Society in Israel, affiliated with the Arab Academic Institute at Beit Berl College, for funding this research.

Works Cited

Bakhush, ʿA. Taʾthir Jamaliyyat al-Talaqqi al-Almaniyya fi al-Naqd al-ʿArabi. Maktabat ʿAyn al-Jamiʿa. 2023. https://ebook.univeyes.com/109589

Barada, M. Al-Riwaya al-ʿArabiyya wa-Rihan al-Tajdid. Al-Hayʾa al-Misriyya li-l-Kitab. 2012.

Di Rosario, G. Electronic Poetry: Understanding Poetry in the Digital Environment. PhD Dissertation, University of Jyväskylä, 2011. https://jyx.jyu.fi/bitstream/handle/123456789/27117/9789513943356.pdf

Eshet-Alkalai, Y. “Digital Literacy: A Conceptual Framework for Survival Skills in the Digital Era.” Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia, vol. 13, no. 1, 2004, pp. 93–106.

Eskelinen, M. Travels in Cybertextuality: The Challenge of Ergodic Literature and Ludology to Literary Theory. PhD dissertation, University of Jyväskylä, 2009.

Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5, 1-4. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

Electronic Literature Organization. Electronic Literature. 2022. Accessed June 24, 2024. https://eliterature.org/

Gourram, Z. Al-Adab al-Raqami: Asʾila Thaqafiyya wa-Taʾammulat Mafahimiyya. Ruʾya li-l-Nashr wa-l-Tawziʿ. 2006.

Hammond, A. Literature in the Digital Age: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press. 2016.

—. ‘Teaching with Literature in the Digital Age’. Adam Hammond, https://www.adamhammond.com/teaching-litda/. Accessed 16 Sep. 2025.

Hayles, N. K. Electronic Literature: New Horizons for the Literary. University of Notre Dame. 2008.

—. Electronic Literature: What is it? The Electronic Literature Organization. January 2. 2007. https://eliterature.org/pad/elp.html

—. How We Think: Digital Media and Contemporary Technogenesis. The University of Chicago Press, 2012.

Ivasheva, V. On the Threshold of the Twenty-First Century: The Technological Revolution and Literature. Progress Publishers, 1978.

—. Al-Thawra al-Taknulujiyya wa-l-Adab. Translated byʿA. Salim, Al-Hayʾa al-Misriyya li-l-Kitab. 1985.

Joyce, Michael. Of Two Minds. University of Michigan Press. 2002.

Keeney, Paul, and Robin Barrow. Academic Ethics. Ashgate. 2006.

Kress, Gunther. Literacy in the New Media Age. Routledge. 2003.

Landow, George P. Hypertext: The Convergence of Contemporary Critical Theory and Technology. Johns Hopkins University Press. 1992.

Martine, H. J. Nashʾat al-Tibaʿa fi al-Maghrib. Translated by ʿAbid, Alexandria Library. 2005.

Merkaz Mada LeTekhnologiyot Lemida. Learning Technologies in Higher Education in Israel [in Hebrew]. National Knowledge Center for Learning Technologies. 2002.

Mishra, Punya, and Koehler, M. J. Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, vol. 108, no. 6, 2006, pp. 1017–1054.

Najm, al-S. Al-Thaqafa wa-l-Ibdaʿ al-Raqami: Qadaya wa-Mafahim. Amanat Amman. 2008.

Nasrallah, A., & Younis, E. Al-Tafaʿul al-Fanni al-Adabi fi al-Shiʿr al-Raqami. Markaz Abhath al-Lugha al-ʿArabiyya. 2015.

OECD. The Future of Education and Skills: Education 2030. OECD Publishing. 2018.

Serafini, F. Reading Multimodal Texts in the 21st Century. Research in the Schools, vol. 19, no. 1, 2012, pp. 26–32.

Simanowski, R., Schäfer, J., & Gendolla, P. (Eds.). Reading Moving Letters: Digital Literature in Research and Teaching. Transcript Verlag. 2010.

Spires, H. A., Paul, C. M., & Kerkhoff, S. N. Digital Literacy for the 21st Century: Advanced Methodologies and Technologies in Library Science, Information Management, and Scholarly Inquiry. IGI Global. 2019. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-7659-4.ch002

Unsworth, L. “Literacy Learning and Digital Technology: Implications of Multimodal Texts.” The Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, vol. 29, no. 2, 2006, pp. 38–51.

Walsh, M. “Multimodal Literacy: What Does It Mean for Classroom Practice?” Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, vol. 33, no. 3, 2010, pp. 211–239.

Younis, E. Arabic Literature and Social Media. Lexington Books. 2024.

Younis, E. “Rhetoric in Visual Arabic Poetry: From the Mamluk Period to the Digital Age.” Texto Digital, vol. 11, no. 1, 2015, pp. 118–145. https://doi.org/10.5007/1807-9288.2015v11n1p118

Cite this article

Younis, Eman and Hisham Jubran. "Attitudes of University Students Towards Digital Literature: Correlation Between Exposure and Learning" Electronic Book Review, 28 September 2025, https://doi.org/10.64773/6wyx-zxyz