Parrots on a Wet, Black Bough: Facing into AI Art

Stuart Moulthrop's meditation on AI artistic production explores the pareidolia at play in human interactions with generative models while arguing, via Wim Wenders' Until the End of the World (1991) and Greta Gerwig's Barbie (2023), for a loving approach to humanity's newest tools.

You saw that face for a second out of the corner of your eye. Or… did you? It’s time to play Apophenia! The crazy game where everything is made up IN YOUR MIND! Yes, it’s that wacky preverbal hominid self that boots you into consciousness, attempting to process a media ecology blasting past a million times faster than evolution prepared it for. And here’s your host…

- McDaid, Note 12.

Contrary to how it may seem when we observe its output, [a language model] is a system for haphazardly stitching together sequences of linguistic forms it has observed in its vast training data, according to probabilistic information about how they combine, but without any reference to meaning: a stochastic parrot.

- Bender, Gebru, McMillan-Major, and Shmitchell

[1] “The human outside the human”

This essay is concerned with many things: the apparition of faces, apophenic1 and otherwise; an emerging immachination of word and image; seductions and hazards of algorithmic culture; the enduring revelations of cinema; and above all, the ways we can understand humanity in a media ecology that accelerates past understanding. This work proceeds by folding together diverse mediations and moments, by colliding paranoid and reparative reading, and above all, through what Sarah Kember and Joanna Zylinska, following Henri Bergson, call intuition:

Antithetical to knowledge-as-we-know-it, intuition opens us to the possibility of knowledge-as-it-could-be and eschews generalities for specificities, representations for a certain realism toward events in process. It also implies a different mode of communication—more analogical, imagistic, metaphorical—that might seem anathema to the conventional scientist or even the more professionalized humanities scholar, but not, perhaps, to the philosopher-feminist or the artist (Kember and Zylinska, 26).

The “specificities” in play here include two essentially unrelated films and an ongoing digital obsession, part of which involves inspecting “the paper at the bottom of the stochastic parrot’s cage,” as one respondent astutely notes (Rogers).2 Scabrous as it may be, this effort is at least tenuously connected to a higher enterprise, informed by Zylinska’s interventions in AI Art: Machine Dreams and Warped Visions (2020) and The Perception Machine: Our Photographic Future between the Eye and AI (2023). These studies build foundations for understanding machinic co-creation through critical-creative practice, offering insights for further exploration. “My overarching proposition is that not only does photography have a future but also that it actually is the future,” Zylinska writes in the later book (7). Identification with the future does not imply utopia, however. In her earlier account she observes:

Gradually a new sense of ‘being human’ is therefore emerging [on social media platforms], consisting of gestures, bodily movements, voice and language affectations, needs, desires and preferences drawn from the multiple data available online and then transmuted by the deep learning networks into what counts as ‘the human experience.’ But this is not a Black Mirror scenario in which avatars will look like us, generating a Blade Runner-like confusion over true human identity. Rather, the YouTube-generated sense of being human is premised on the recognition that, instead of positioning the human against the machine, AI exponentially amplifies the knowledge shared by marketing experts with regard to our desires and fantasies, while being much quicker and much more efficient at actualizing them. We can therefore suggest that AI dreams up the human outside the human, anticipating both our desires and their fulfilment (Zylinska 2020, 70-71, emphasis original).

That italicized phrase is intoxicating in every sense including the pharmacological. Its speculative possibilities are enticing—as explained in the rest of this essay— but beware of side effects. Zylinska arrives at her numinous expression through extended consideration of digital aesthetics, including an essay by the Polish writer Jacek Dukaj, who updates and inverts the Benjaminian notion of aura. “[I]n the times of AI, human life is the only auratic form of art left to us,” Zylinska paraphrases (2020,70). Life converges with art, but by means of platforms and algorithms that amplify “the knowledge shared by marketing experts.” It is worth noting that such information is generally not “shared” by its subjects but extracted in non-consensual ways. It is not data freely given but information extracted, which John Cayley aptly calls “capta” (Cayley).

Our moment may not be some Charlie Brooker or Ridley Scott dystopia, but neither is it the happy end of history. As the ambivalent subtitle of Zylinska’s first book indicates, uncertainty rules. The fascination of “the human outside the human” stems from its deep ambiguity and the many unresolved questions onto which it opens.

I will turn eventually to literal constructions of “human outside the human”—portraits and effigies—but I start with more abstract mediations, those algorithmic processes in which Zylinska finds basis for a new sense of being. Social media are major players here, along with a current fascination with digitally generated imagery. Describing this practice as “remediated photography,” Zylinska asks, “what does [it] look and feel like to the human observer?” (2023, 4). Her own experiments are deeply instructive, especially the “redreamt” cinema of “AUTO-FOTO-KINO”, of which more eventually. In its more modest way, this essay also mixes or enfolds photography, cinema, and writing in response to the same fundamental question. What can machinic co-creation show us, and more importantly, what structure of feeling does it call into being?

From 2022 onward, popular tools for AI-assisted image creation— Midjourney, Dall-E, Stable Diffusion, among others—have attracted millions of users, giving rise to a significant technocultural practice. This remediation of photography is still so new that it lacks a widely accepted name. Chris Chesher and César Albarrán-Torres propose autolography, marking the conjunction of computation (automatos), word (logos) and image (graphos) (Chesher and Albarrán-Torres, 57). Autolography, eliciting images through verbal prompts to an AI system, belongs to the larger category of invocational media (Chesher 2), technically incomprehensible systems to which people issue the technological equivalent of prayers.

Much of the appeal of autolography—perhaps its addictiveness, as Sherry Turkle or Natasha Dow Schull might say (Turkle; Schull)—stems from an interplay of invocation and evocation. Users are encouraged to try fanciful concoctions, for instance, “an adorable, fashionable aardvark, standing on the street in the Harajuku district” (Stable Diffusion). The image resulting from this prompt may match some or all these terms, featuring a long-snouted animal wearing human clothes on a Japanese street, but there will likely be divergences as well. Are we familiar enough with Harajuku to judge its depiction? Who knows what an urbane aardvark is supposed to look like, outside the pages of Cerebus? How should the parameters “fashionable” and “adorable” be interpreted? Is interpretation the right word here? Mysteries abound. We can have only foggy notions about the means of production involved in this transaction, and the results are equally uncertain. What we wish to see is not necessarily what we get. At least in its early days, AI art can be a curiously imprecise proposition, manifesting a strong element of slippage or play.

The whole business often lands on the ludicrous side of the ludic. Zylinska compares the aesthetics of AI imagery to the casual game Candy Crush: “a dazzling spectacle of colours and contrasts” (2020, 76), producing “an odd combination of the fuzzy, the mindless and the bland” (2020, 72). Written before AI art became mass distraction, her remarks were prescient. In my experience, image generation offers a fountainhead of iterative kitsch with (indeed) the attention-fixing power of a phone game. Over many months, using versions of the Stable Diffusion image model, I compiled a gallery of renderings collected as “Unstable Confusion” (Moulthrop). A number of these images explore what Thomas Pynchon called “the high magic to low puns” (Pynchon 1966, 96). Some examples: an anthropomorphic rabbit drinks whiskey (“Hare of the Dog”); a floppy-eared dog gives a wide-eyed stare (“Short Attention Spaniel”); a woman stifles a yawn while ignoring the northern lights (“Aurora Boring Alice”); well-dressed ladies of a certain age play poker (“Dowagers Do Wagers”). A large part of the fun here lies in simple-minded wordplay.

However, sometimes the images evoked by these invocations offer something more than idle entertainment. In my earliest encounters with Stable Diffusion I avoided elaborate expressions, using prompts of only a few words to more fully test the potential of the underlying mechanism.3 On at least one occasion, this led to a remarkable result:

The prompt for this image was the single word “metaselfie”. I had no doubt Stable Diffusion could produce examples of handheld self-portraits, given their frequency in its training set, but I wondered what the system would do with the “meta” element. As you can see, the answer was more than I may have thought. The image suggests a trick of digital editing: a human head framed in the outlines of a smartphone screen, stuck seamlessly onto a proportional chest and shoulders. The picture conflates photograph and photographer, which is the raison d’être of selfies, and adds a duck-rabbit trompe l’oeil, with maybe a hint of the monolith from 2001: A Space Odyssey. There is a lot going on here — much in the eye of the beholder, no doubt, though arguably not all.

None of the effects in this image were specified in the prompt. The distorted, bespectacled face of the selfist calls to mind Parmigianino (and thus maybe Ashbery) but is basically factitious. The curious geometry, with its Escher-like “strange loop” (Hofstadter 2), comes completely unbidden. Also notable is the textured background, which resembles a fan of shattered safety glass. The suggestion of broken glass could evoke the materiality of cellphones, or perhaps the concept of transgression or rupture implicit in the “meta” move. To dismiss this feature as random flourish seems negligent, though it is hard to know what to say about it. Strictly speaking, it has no meaning, in the sense of intentional expression, but that does not make it insignificant. “Metaselfie” begs for interpretation, even as we are reminded by Chesher and Albarrán-Torres, along with the authors of the “Stochastic Parrots” paper, that it is a mathematically determined convergence of possibilities. Perhaps, as McDaid warns, it is at least partly apophenic — MADE UP IN MY MIND—though another possibility remains.

As I learned after writing my prompt, “metaselfie” is a recognized sub-genre comprising images of people taking selfies. A multitude of examples exist online. AI image generators base their output on vast compilations of digitally available pictures, of which some significant number may be tagged with the term “metaselfie”. Could Figure 1 simply distill these images? Have Photoshop artists duplicated its composition enough times to create an indexable visual style? These doubts are reasonable, but they lack supporting evidence. Search engine queries on “metaselfie” yield some compound images where the view from the main lens is displayed on the phone screen, turned toward a second camera for capture. These images have a rough similarity to the trick construction of Figure 1, but they are far from identical. In a first-order survey at least, no examples include the collapsed distinction of photographer and photograph. An image-based search using Figure 1 returns no close matches.

To be sure, the picture I co-created with Stable Diffusion is an illusory construct, more figurally compelling than a Rorschach blot, but just as subject to projection. As McDaid suggests, a tendency to fabulate presence seems deeply entwined with consciousness. We could speak of apophenia or pareidolia, but also another kind of illusory investment: the ELIZA Effect in which users naively attribute complexity to computer programs that are in fact crudely formalistic (Wardrip-Fruin, 32 ff.). The namesake of the fallacy was Joseph Weizenbaum’s experimental text generator of 1966, the first ancestor of all chatbots, one variant of which imitated a conversational style associated with Rogerian psychotherapy. The program cleverly parsed any statement passed to it, repeating key elements with an eliciting prompt (“WHAT MAKES YOU SO INTERESTED IN sinister machine intelligence?”). Unlike many of today’s AI promoters, Weizenbaum made no cognitive claims for his invention. Indeed, he devoted much of his later career to systematically debunking the fantasy of machine intelligence (see Weizenbaum; Berry and Marino). Nonetheless, ELIZA’s users were notably prone to ascribe intelligence to the software. In those first encounters with Weizenbaum’s creation, we might find the primal scene of invocational media: our compulsion to over-invest in machinic mysteries. The current pursuit of artificial intelligence flagrantly disregards ELIZA’s lesson.

Yet none of these objections can entirely dispel the significance of “Metaselfie”. Prestidigitation, tricks of hand and eye, are at least “half-real”, to borrow liberally from Jesper Juul’s description of video games (Juul). Like games, AI images have material dependencies (databases, algorithms, server farms) and through these means produce illusions that capture the attention and engagement of the beholder— largely through the element of surprise. The curious qualities of Figure 1 represent an emergence premium, an eruption of effects that gives the image an unanticipated depth of potential meaning. This metastasis is at least half real and perhaps a bit more. Fittingly, the phenomenon of emergence is centered on portraiture of faces. Facial images are among the most powerful ways in which typically sighted people define “the human outside the human:” the readable features of others.4 The next stage of my autolographic work led away from the reflexiveness of the selfie to a category that might be considered its antithesis: portraits not of a putatively present self, but of someone who does not exist.

[2] Portraits of imaginary people

Zylinska notes in AI Art: “Given the source material used to train machine vision, it is perhaps unsurprising that the canvas for such experiments is frequently provided by human faces” (78). One of these experiments is called Portraits of Imaginary People (Tyka), a title that might denote a micro-genre of AI art. I will have more to say about this genre and my relation to it, but first some thoughts about the phrase itself. Taking a long view of art history, portraits of imaginary people may seem tautological. What depiction does not draw on invention or imagination? Think of Holbein painting Henry VIII with those stupendous shoulders, or Cromwell with a writ stuffed in his hammy fist. When it comes along, photographic portraiture inclines toward the veridical but arguably still involves an exercise of temporal synecdoche in the selection of the shot. As Roland Barthes observes, “the Photograph mechanically repeats what could never be repeated existentially” (Barthes 4). The moment of exposure is tangent to the curve of life. The choice of that moment may, in some cases at least, count as work of imagination.

Arguably, though, imaginary portraiture takes on new meaning with digital generation. Zylinska discusses several artists aligned with computer image research. In the efforts of each, a program or algorithm constructs an original picture based on structural analysis of images in a large data store such as Flickr, the British Library, or the Internet Archive. The products are literally image-inary portraits, pictures generated by the graphical equivalent of stochastic parrots which have (allegedly) learned to make images by processing the trove. In her later book, Zylinska details her “AUTO-FOTO-KINO” project, which generates a new photo-roman from the component images of Chris Marker’s La Jetée (2023, 119 ff.). This effort might be seen as an imaginary portrait of a film. All these cases involve images made from images, which indeed might be the general formula for art, but with reference and transformation invested in software instead of internal human processes.

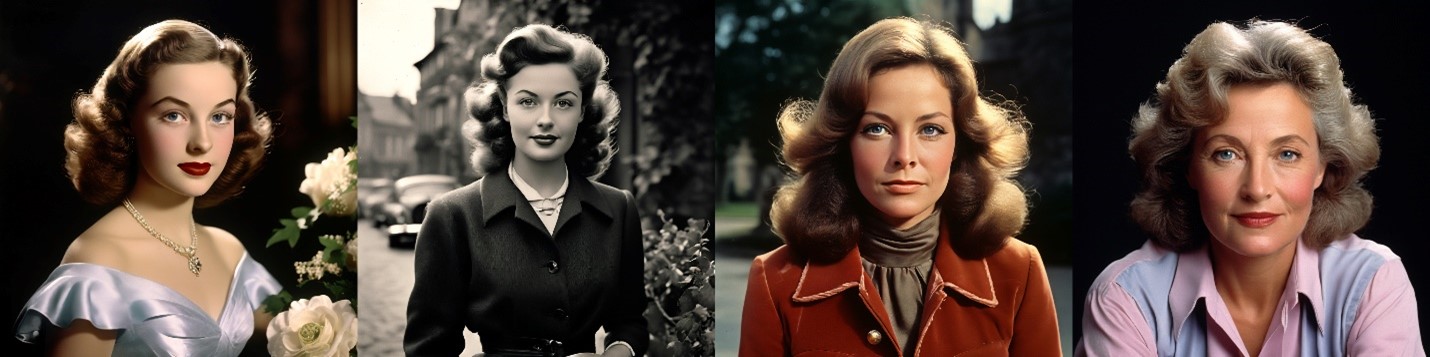

Autolography keeps humans tenuously in the loop, at least as writers— or in this case, a writer who is also a certain kind of moviegoer. In April 2023, a few months into my exploration of AI imaging, I prompted Stable Diffusion for a “Portrait of Claire Tourneur”. Though the name may also belong to some actual person or persons, I take it from a character in a film—about which more eventually—but first the images. For this run I configured Stable Diffusion to deliver four iterations on the prompt in a two-by-two grid. Here is the result, arrayed clockwise in order of generation:

The series offers four brunettes, notionally European, possibly French. Characteristically, for this early stage of Stable Diffusion at least, all four women are white, and given hair, dress, and adornments, they belong to the middle class. As Safiya Noble or Lillian-Yvonne Bertram might observe, the consistency of these images reflects infrastructural biases of race and class (Noble; Bertram). Given a feminine, Francophone name, the Stable Diffusion of 2023 would not envision a woman of color, even though “Claire Tourneur” might hail as plausibly from Algeria or the D.R.C. as France or Canada. Similarly, the system seemed unable to imagine a “portrait” of anyone who was evidently a laborer. Between 2023 and 2025, I iterated the “Claire Tourneur” prompt dozens of times. Though there were notable variations, including a large range of ages and a few Claires presenting as male, all the faces were pale, with a marked tendency toward redheads.

It is hugely important to call out this institutional whitewashing. My neglect of that subject is apparent and regrettable, crossed by an interest in another class-and-gender-ridden imaginary—a certain late-20th-century movie—on whose vision of a certain white, affluent woman I have fixed my attention. However indulgent or erroneous this may be, I begin with some arresting features of Stable Diffusion’s initial performance. I am interested in a type of consistency in those images from early 2023 but as a matter of personal fiction rather than infrastructure.

Given obvious differences in composition, lighting, and tone, the first impression of the Figure 2 set may be its variety. The two lower images, though constructed from opposite angles, bear some resemblance in overall facial shape and the contours of nose and brows. Continuity is not as strong in the upper images, given the evident difference of age, but there may be enough to suggest that the woman in the second image (counting clockwise) might be an older version of the person at upper left. This notion might suggest a similar relation between the images in the lower row, who could perhaps be the same woman photographed a few years apart. These hints of temporal placement suggest a rearrangement of the set:

This re-ordering places the images according to photographic qualities, styles, and (however illusory) apparent artifactual age. The leftmost image is a soft-focus “glamour shot” giving its subject movie-star treatment. Still popular, these portraits had a heyday in the 1930s and 40s. The clothing and hairstyle of the first Claire seem evocative of this period. The greenish tone suggests photochemical aging. The next image is also monochrome, clearer in tone and more sharply focused, giving it a documentary quality. The bobbed hairstyle could be the same permanent wave worn by the first Claire, more casually presented. The clothes are enigmatic in cut and feature—the rendering is problematic — but they have a quasi-military look that might suggest World War II or its aftermath. The same seems true in the third image, where the blouse, though worn with an informal open collar, calls to mind a uniform. The monochrome bars flanking the picture suggest a passport or ID photo mounted on a cardboard matte. The hairstyle of the third Claire is no longer a coiffed bob, but a lower-maintenance cut, a bit grown out. The last image is in an incongruous full-color style that calls to mind Kodachromes of the 1960s and ’70s. The hairstyle is once again formal, and the outfit, though only vaguely rendered, has textural hints of double knit that reinforce its period placement.

Seeing these images as a putative time sequence invites closer consideration of the four faces. In some ways, the last looks very little like the first. The face is longer, the jawline considerably softened and the lips less full, though all of this could be consistent with an age difference of three or four decades.5 As I have suggested, it may be easier to see continuity between the first and second, and the second and third images. The pattern is far from seamless, especially in the transition from the second to the third Claire, but comparison with another series is instructive:

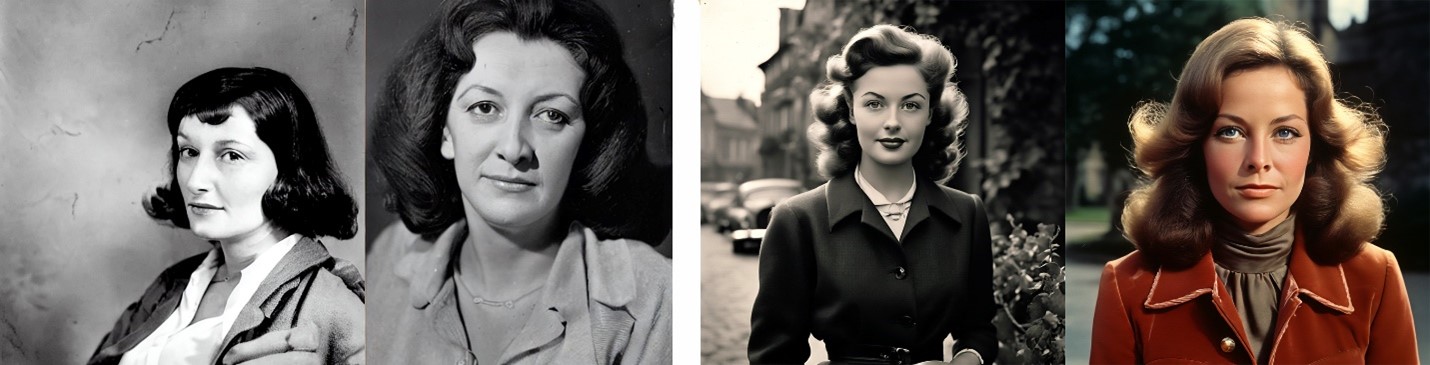

I co-generated this sequence about a year after the images in Figures 2 and 4, to test what Stable Diffusion could do when asked explicitly for a time-and-age series. The images were produced using four discrete prompts in immediate succession:

Claire Tourneur in 1940 as debutante

Claire Tourneur in 1955 at the start of middle age

Claire Tourneur in 1970 in late middle age

Claire Tourneur in 1985 in older age

For all its egregious whitewashing, this set is more aesthetically satisfying than the 2023 example—among other things, Stable Diffusion’s consistency of aspect ratio, and its treatment of eyes and clothing, have considerably improved. The costumes, hairstyles, and settings have strong historical plausibility. The similarity of faces seems tighter as well, though again there is perhaps more likeness between each of the lateral pairs (1-2 and 3-4) than overall. It is worth remembering that any resemblance at all is remarkable. Notice that the Claires in this set look very little like those from 2023. Continuity within the later sequence is doubly remarkable. As they are products of discrete operations, there is no evident reason for consistency, other than whatever constraint the name “Claire Tourneur” places on the system. There is no indexical Claire to serve as reference. Every image is an invention.

The later experiment imposed the temporal scheme of a life series, but this pattern can also be seen in the earlier, unconstrained instance. At the very least, these experiments again suggest that autolography may yield something more interesting than mindless kitsch, at least in cases where evocation exceeds invocation. Both “Metaselfie” and the initial Claire series yielded more than I anticipated. The double diachrony of the image set evokes a photographic biography, a haunting suggestion of unified persona—if not a veridical Claire, then at least an elaborated fiction.

This is pure fantasy, of course: my Claire might as well be named ELIZA. The notion of a unified character is made up in the mind of this perceiver in a transaction that zooms past willing suspension of disbelief into active speculation. Consider the weakest point of the visual evidence, the transition from the second to the third image in each set (“start of middle age” to “late middle age” in the denominated series). These images may be the least objectively similar, thus the most pareidolic. Seeing them as traces of the same woman could entail a story. What influence, aside from gravity, accounts for the longer face and wider mouth of the woman in the rightmost image, compared to the thirty-something to her left? Likewise with the other pair, as we move from the Mona Lisa pose of the second Claire of 2023 to the frank regard of her successor, what passages are implied—lovers come and gone, marriages, divorces, children borne, bottles emptied, cigarettes smoked? What makes up the curve of life to which these moments are tangent?

Given this flight of fancy, the most logical response is, probably, snap out of it.6 A language model, as Bender and company instruct, is a mindless mechanism, a “stochastic parrot”. That characterization may not be entirely fair to parrots and other animal communicators, but it is properly skeptical of humanity.7 More useful may be Jon Ippolito’s critique of AI metaphors, in which he points out that language models are more accurately understood in terms of inanimate thermodynamic systems. In his view, a better model for ChatGPT or Stable Diffusion is a fresh cup of coffee (Ippolito).

The ELIZA Effect is relentless, however. Whether the source is parrot, hot java, or burning bush, humans tend to attach language to voice. On this point the authors of the “Parrots” paper quote the poet Maggie Nelson: “Words change depending on who speaks them; there is no cure” (Bender et al., 618). As with parrots, so with portraits: there may also be no remedy for the compulsion to interpret a series of images as traces of a life, arranged with a certain intention, even when we are dealing with processed ensembles of signs. There is no real life behind these illusory life series, yet it is nearly impossible to resist the apparition of faces. An instinctual drive to see them as signatures of other selves may indeed be one origin of “human outside the human”.

In the case of “Claire Tourneur,” however, that outside move calls for deconstruction. Its subject is not simply imaginary but previously imagined. I borrowed the name from an existing fiction. Claire is not so much half-real, to recur to Juul’s formula, as something more complicated: not integer but fractal. It is time to say more about the invocation of Claire Tourneur.

[3] Motion pictures…

In Wim Wenders’ 1991 film Until the End of the World, Claire Tourneur is a primary character played and partly created by the late Solveig Dommartin (Wenders). Indeed, there is a certain uncanny resemblance between Dommartin’s Claire, as she first appears in the film, and one rendering in the Stable Diffusion run of 2023.

Several things need pointing out here. The still image of Dommartin at the wheel is part of the repository of images on which various early versions of Stable Diffusion were trained. The photo may well have been indexed with the name of Dommartin’s character. However, the LAION 5b image set contains nearly six billion items, so the odds against such a match seem appreciably long. Further, image generators are not search engines. They do not simply retrieve pictures but fabricate novel arrangements of pixels using data on which they have been trained. It is probably pure coincidence that Stable Diffusion’s Claire (strictly speaking, the third of a fourfold run) should look like Dommartin. Even within the film, the image of Claire in pageboy bob is fleeting. Soon after the car scene, Claire doffs the black wig and shakes out her natural hair, declaring, “I’m really a blonde,” as she remains for the rest of the film. This again tilts the odds against direct reference. I have run the Claire prompt many times without reproducing the cinematic resemblance.

If the echo of Wenders and Dommartin was purely stochastic, my invocation of Claire Tourneur—both the name and its meaning—is quite the opposite. I follow the fundamental logic of invocational media. On the processual side, these systems are unfathomable. We cannot say definitively how a tool like Stable Diffusion goes from a prompt to a rendered image. The work involves both reference to training data and a reciprocating set of transformations in which those data are reduced to noise (diffused) then re-resolved into a new, coherent image. Using an invocational system requires meeting this bottomless mystery with a countervailing clarity of purpose. I chose Claire as the subject of these portraits because the story Wenders tells about her leads me to some crucial questions about AI art.

Until the End of the World is perhaps too many things: limited-series television crammed awkwardly into theatrical runtime; an excuse for an epic late-80s soundtrack; a road movie; a love triangle; and a work of speculative fiction that gets some things right about the coming century. The film both is and is not an apocalypse story. It depicts a technological cataclysm caused by nuclear explosions in orbit, but this happens about two-thirds of the way in, and the soundless pyrotechnics feature as background for a screen kiss. The film is in fact transapocalytic, concerned with how its characters carry on, not until the end, but beyond. In this sense, it might be said to carry an important message for later moments of techno-anxiety. (It was a must-watch on Y2K night.)

Claire Tourneur’s story is arguably the major vehicle for this message. At the start she has just ended an affair with Gene Fitzpatrick, a stymied novelist. Through a chain of accidents, she becomes involved with an accused industrial spy named Sam Farber, a maverick neuroscientist whose exploits are meant to finance his work on (of all things) machine vision. Sam has created a device that reads activity in the visual cortex, producing transmissible video recordings. His immediate desire is to become a seeing surrogate for his blind mother.

For some reason Sam cannot master his device, but Claire succeeds, discovering in the process that it can capture dreams as well as waking vision. This proves disastrous, as Claire becomes fixated on a nightmare that has plagued her since childhood, a scenario of loss, abandonment, and literal falling (“pourquoi tombe?”). As the wired world collapses around her, Claire obsessively re-views her dream on a handheld video player until the batteries fail, sending her into howling withdrawal.

The fourth chapter of McLuhan’s Understanding Media is called “The Gadget Lover: Narcissus as Narcosis” (McLuhan). It is concerned with the way dependence on technologies leads to “autoamputation,” the distortion of the human condition under the “stresses” of automation:

With the arrival of electric technology, man extended, or set outside himself, a live model of the central nervous system itself. To the degree that this is so, it is a development that suggests a desperate and suicidal autoamputation, as if the central nervous system could no longer depend on the physical organs to be protective buffers against the slings and arrows of outrageous mechanism (McLuhan, 43).

Though McLuhan’s androcentric pronouncements may cause cringe, they shed some light on “the human outside the human”—the subtitle of his book is after all “The Extensions of Man.” More importantly, they illuminate Claire’s dream addiction. Farber’s cortical recorder literally extends the central nervous system. Though it is meant to do good, its addictive potential makes it an “outrageous mechanism.” Claire’s fixation with reified dreams cuts her off from the people around her, an ultimate “autoamputation.” In many ways, Claire is the poster child for McLuhan’s “Narcissus narcosis.” Until the End of the World came out long before cellphone video and social networks, but the image of Claire fetally crouched over her device was chillingly prescient.

This moment is not the end, though. Claire struggles with her dependency, moves into recovery, and ultimately rises in triumph. The final scene is set a few years after Claire resumes her life. The global electronic collapse has been swiftly repaired. High technology is back online but with notable differences in form and purpose. Instead of ominous nuclear satellites, we learn of an orbital outpost operated by “Greenspace,” whose astronauts scan the oceans for “pollution crimes”. These last moments uncannily anticipate our present onscreen lives, showing us a Zoom call avant le lettre where Claire’s friends wish her a happy thirtieth birthday—in space. Claire’s dream of falling has turned into orbital motion—flying and falling, or as Claire’s ex-lover titles the novel that marks his own return to grace, A Dance Around the Planet. Her vision, once fixed inward on the eruptions of her unconscious, turns outward in defense of the environment.

Though Wenders is said to have chosen Claire’s surname in homage to the director Jacques Tourneur (Johnson), the name may have further resonance. A turner is the operator of a lathe, a worker in revolutions. Metaphorically, Claire is the turner or pivot on which the moral axis of the film rests. She is the clear turner whose upward or outward trajectory reveals a restorative future. Claire is of course an invention, a congeries of words and images, a name attached artfully to a photogenic face and a shared set of stories. She emerges from the dream machine of cinema, allowing me to invoke her within the newer machinery of generative AI. In this transformation she gives rise to further illusions and half-realities, and perhaps another lesson as well.

To invocation and evocation, we may add implication or folding.8 Invoking Claire Tourneur in AI art is less turn than fold, arguably made in pursuit of something more than jejune nostalgia. I fold Wenders over Stable Diffusion, cinema over autolography, the crazy optimism of the 1990s onto our Screaming Twenties. Above all, I enfold—or collide— the eco-positive dance around the planet with our present “human outside the human”, if only to call out the stark difference in these visions and the structures of feeling from which they arise.

This topology is not limited to the visual; musical manipulations are also possible. Wenders’ credit roll, played over the eponymous U2 hit, perversely calls to my ear a different track, a less popular song from an earlier decade. That deep cut calls up another mood, not Bono’s incantatory bombast but a more laid-back California vibe, evoking perhaps those “Quiet Days at Malibu” with which Joan Didion marked the ominous end of the sixties. The song is Neil Young’s “Motion Pictures (for Carrie)” which ends with these words:

Well, all those headlines,

they just bore me nowI’m deep inside myself,

but I’ll get out somehow,

And I’ll stand before you,

and I’ll bring a smile to your eyes.

Motion pictures,

motion pictures (Young).

There is something to be said for getting outside oneself, the better to transcend the doomscroll of always-arriving apocalypse.9 Motion pictures, indeed: even if Claire’s orbital dance is ultimately constrained by gravity, curved into the equipoise of flying and falling, it nonetheless takes her to a plausible exterior, a point from which to look back on a shared, planetary reality. This is a happy ending. All the faces on that birthday call have smiling eyes.

However, even motion pictures are tangents to time’s curve, or “dams placed in the way of the stream of history,” as Zylinska quotes Willem Flusser (2023, 145). In 1991, the outside move remained imaginable, the production of moving images amenable to dreams of literally higher purpose. A road movie, with its dance around the planet, still looked like a way to get somewhere. Consider where we find ourselves three decades later, at least in terms of our visionary technologies. In contrast to Claire’s ascent to orbit, what can “outside” mean in “the human outside the human?” What space does it imply, and what oikos or ecology can we imagine there? If that phrase points only to the conjuring tricks of machine muses and stochastic systems, extractive databases and deeply inscrutable algorithms, then where is the outside and what is the human? These are hard questions, but they are not the end of the matter.

[4] Extensions of woman

Fast forward or smash cut to the heyday of immachination, summer of 2023, from which I take yet another cinematic overlay, one which again features apparition, invocation, and the name behind a face. The film is Greta Gerwig’s Barbie. Like Until the End of the World, it is an extravaganza with notable flaws, though that may be the only point of resemblance. In contrast to Wenders’ opus, Gerwig’s was an historic hit, the first woman-directed feature to gross a billion dollars (Barnes). Bringing this film to the discussion may amount to parataxis, leaving the reader to wonder, why this? Barbie is an overtly kitschy, entertainment-positive fantasy that fuses no-wave (we might say “beach”) feminism with raging commodity fetish. Consider the moment when Ken, having usurped the Dream House, tosses Barbie’s wardrobe into the street, with each item freeze-framed and glossed for consumer reference (Barbie, approximately 1:05:00). The scene drips with post-postmodern irony, which is to say, its contradictions pre-emptively refuse any attempt at resolution: been there, deconstructed that; freeze-framed the T-shirt. Barbie abounds with this kind of ideological vertigo. In its disingenuous mockery of corporate patriarchy, the film stages the false consciousness of Barthes’ “Operation Margarine” (Barthes) with the overamplified blare of a Broadway revival. It has been reasonably accused of “marketing…‘feminism’ itself as product” (Gillis and Pellegrini, 496).

And yet, Barbie may not deserve an unmitigated pan. For all its problems, the movie resonated powerfully with hundreds of millions of women. In the introduction to a special issue of Feminist Theory devoted to the film, Stacy Gillis and Chiara Pellegrini write:

Barbie is a film acutely aware of its politics, and in some ways it works to subvert and satirise in advance any ideological readings of itself as text and as product; at the same time, it is a film produced by a late imperialist capitalist system, which innately reifies and commodifies consumption and inequity. Weird Barbie may have meta-referentially exhorted us to not “think about it too much,” but it is too late now—we have thought about Barbie far too much to stop here (Gillis and Pellegrini, 500).

Full of trickery and self-regard, Gerwig’s film indeed rewards study. In one of its first serious considerations, Caetlin Benson-Allott assigns the film to a “Girlhood Trilogy” with Lady Bird (2017) and Little Women (2019), a set that poses “important questions… about girlhood and middle-class white American women’s quest for autonomy and self-determination” (Benson-Allott, 67). Benson-Allott’s insights, and her critical framework in particular, are essential here, and we will come back to them. For the moment, consider the way Barbie imagines girls and women as technological or mediated subjects. We might find in Gerwig’s fantasy a revisionary update of McLuhan: a discourse on the extensions of woman. That is, after all, one way of understanding the world of Barbie. The serialized doll, with all her variations of complexion and hair (overlaid on an infamously constant physique10) is another way of dreaming up the human outside the human. Yet the many avatars of Barbie—President, Doctor, Physicist, Writer, Weird, etc.—do not represent the only system of displacements in this densely over-coded film. With respect to pareidolic anxieties, a certain early moment looms large.

About a half hour in, after Barbie and Ken arrive in Los Angeles and momentarily split up, Barbie encounters a woman of advanced years sitting on a park or bus stop bench.11 “You’re so beautiful,” Barbie says to the woman, who answers, “I know it.” The encounter ends as Ken returns with an important clue for their quest, to which the narrative immediately shifts.

Consisting of eight shots and two lines of dialogue, this moment takes up only a few beats. In this film, however, small details may matter disproportionately. For all its goofy pageantry, Barbie is semiotically saturated, bristling with in-jokes, asides, meaningful needle drops, and researchable references. This brief exchange has several levels of meaning. Allowing for a certain perversity, it may offer a key to understanding the film’s divided consciousness.

At its most immediate, the encounter shows Barbie beginning to understand the real world. Just before it happens, as she looks around at people in the park, her newly humanized mirror neurons go into overdrive. Two friends sharing a joke make her laugh; a man in a posture of suffering brings her to tears. As the camera pulls back to show another person sitting on the bench, she experiences a revelation. There was no aging in Barbie Land until “irrepressible thoughts of death” intruded, so the transmigrated doll has never seen an older woman. Meeting such a person teaches Barbie that beauty is not tied to a single, static ideal, but can transcend time and change. This gives the scene a convenient function in terms of the heroine’s journey to enlightenment, but that is just the first layer.

Several things are noticeable about the character credited as “The Woman on the Bench”. Her appearance is frankly presented, with little attempt to disguise thinning hair and age-appropriate complexion. Also, though her performance is flawless, it carries a hint of naturalism that suggests a non-professional actor. In the context of Barbie’s overall standard of glitz, these incongruities signal a cameo scene.

Most moviegoers have well-defined expectations of cameos, based perhaps on examples from Hitchcock or the Marvel Cinematic Universe. A cameo is a brief polysemic intrusion, often the vehicle for a passing joke, as when Stan Lee is mistaken for Hugh Hefner in Iron Man (2008), or Rob Reiner’s mother quips, “I’ll have what she’s having,” after Meg Ryan’s orgasmic performance in When Harry Met Sally (1989). Like all jokes perhaps, the cameo evokes an intimacy of decoding: I see what you did there. A layer of filmic ontology is pulled back, and we are briefly offered something more than the diegesis. Tom Stoppard famously defined actors as “the opposite of people” (Stoppard, 63). The cameo reverses polarity, setting veridical people within the filmic world. They may not be the opposite of actors—Hitchcock and Lee were celebrities, Estelle Reiner had a stage career—but their doubled identities give them an orthogonal relation to the rest of the players. We might say they are half-unreal.

The cameo makes this complicated subject intensely present, in clear focus, if not close-up. It is worth remembering the artifactual meaning of cameo, an image carved in relief, often presenting a bust or face. A literal cameo centers the face, commemorating and registering identity. The cinematic cameo does this too, but to disruptive effect. The sequence demands additional attention, stretching if not puncturing the film’s illusion. At the heart of this effect is requited pareidolia, when a face seen out of context turns out to be not a trick of the eye but a legitimate presence—that’s who I thought that was!

As it happens, the Woman on the Bench confounds this decoding. Every cameo poses a question of identity. In Barbie, the guessing game has a distinct historical context. It is well known that the designer of the Barbie doll, Ruth Handler, named her creation for her daughter, Barbara. Ruth died in 2002 (Rhea Perlman plays her ghostly presence in the film), but her daughter, born in 1941, was in her 80s when Barbie was made. This seems a plausible age for the Woman on the Bench. Could the avatar of older beauty also be Namesake Barbie?

She is not. The Woman on the Bench is played by Ann Roth (actually in her 90s), the award-winning costume designer for Barbie and Little Women, apparently an esteemed friend of the director. Considering the huge importance of costumes in this film, the cameo brings a different kind of recognition: credit or homage. Its trickiness may also forge a cognitive link between Barbie and her audience. Barbie doesn’t understand the world around her, and neither, perhaps, do we. Feelings flood through her, and vicariously through the viewer. She needs to unfold the meaning of the human world. We—or some of us, at least— are confronted by the mysteries of its representation.

Barbie will complete her sentimental education, becoming human at the end of the story. How far we should go to solve the apparent puzzles of the film, and this cameo in particular, may be less clearly determined. I will posit one more layer of possible meaning in the cameo, derived from what may seem like misdirection or a bait-and-switch. I will suggest a reading of the entire film that could arise from this conjecture. However, I say now that this reading is utterly out of keeping with the overt tenor of Barbie, at odds with its ostensibly primary commitments, deeply and willfully wrong. In this case, however, a wrong reading may prove enlightening.

To a certain kind of reader, who for the moment will remain nameless, the cameo’s focus must represent deliberate choice, considering that so many other details of this film are intentionally contrived. The casting of Roth could not be incidental or accidental; there must have been an artful substitution. The expected, genuine Barbara is displaced by an unknown figure, causing a failure of recognition or pareidolic projection. The face is not the one we think it is; the lady is not who she seems

In the mind of this interpreter, the alleged misdirection has significance far out of proportion to its fleeting screen presence. For this reader, the supposed switch excludes the human Barbara from the story—so that the doll can take her place in the final scene. In that moment, Barbie gives her name as “Handler, Barbara” and thus assumes human identity. This declaration is made on a visit to her gynecologist, calling attention to her reproductive potential. The statement thus places Barbie in a line of descent. She announces herself with her family name first. The doll becomes woman, but not just any woman: she becomes her namesake.

Embracing this admittedly strange reading would make Barbie not a musical-comedy-cum-feminist fantasia, but something very different: a Doppelgänger story of uncanny infiltration. In effect Gerwig’s film would become an analog of Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1955, 1978), or Blade Runner (1982), where alien or artificial beings usurp humanity. If we accept this reading, Barbie’s closest parallel might well be Blade Runner 2049 (2017), in which the replicant Rachel is revealed to have born a child that successfully passed as human. As in that film, a secondary evolution (or creation) entwines with the first. An engineered product enters the human family.

All of which, as stipulated, is very wrong. The reading described here is flagrantly inconsistent with everything Barbie celebrates. It is profoundly cynical, not playful. It blasphemously reverses the moral arc of Gerwig’s story, which moves toward celebration of womanhood. It disregards two of the film’s most humane moments: Gloria’s monologue on the impossibility of women (1:13 and following) and the colloquy between Barbie and the ghost of Ruth Handler (1:40 and following), which makes clear the stakes of choosing the flesh. Worst of all, it betrays the post-Dobbs resonance of the gynecologist scene, which reminds us how female personhood is threatened by patriarchal oppression. In terms of cultural politics, this wrong reading twists Barbie’s liberatory message into a dark parable of Great Replacement. It is Barbie as read by some grotesque influencer from the manosphere, or perhaps the hapless Ken himself.

[5] Reparation

In apology for this exercise in wrongthink, I need to apply the term Eve Sedgwick gave it nearly 25 years ago: paranoid reading. This mode of interpretation asserts “strong theory”, an insistence on decoding, or final, revelatory meaning. It manifests a pathological desire for connection (there are no coincidences), a need for reductive explanations (everything is some kind of plot), and above all, a pervasive sense of threat (even paranoids have enemies). As Sedgwick notes, “the notation that even paranoid people have enemies is wielded as if its absolutely necessary corollary were the injunction, you can never be paranoid enough” (127).

As we used to say in a different context, yes we can. Enough, already: this treacherous distortion of Barbie marks a clear limit for paranoid reading, a correction dearly needed in the face of pervasive revanchism, conspiracy theory, and mutually assured demonization. It is even more appropriate because the threat of replacement now extends not just to tribal enmity, but in the latest onslaught of automation, to core human faculties: language, thought, and imagination. In art and elsewhere, AI threatens its own vector of Replacement. Given the turmoil, hatred, and precarity into which so much of the world has plunged, there seems every reason to shun paranoid reading and put something else in its place.

I come back, as promised, to the theoretical framework Benson-Allott adopts from Sedgwick: reparative reading. Here is how Benson-Allott traces this strain in modern cinematic criticism:

Reparative reading often involves reading against the grain, as Carol Clover does in her pioneering feminist analyses of U.S. slasher films, or privileging more-empowering narrative or formal details over less-affirming compositional choices, as Caél Keegan does in his landmark trans* analysis of The Matrix (Lana Wachowski and Lilly Wachowski, 1999). Reparative readings do not seek to deny the harmful messages their texts may carry or the cultural contexts that lead marginalized audiences to search for emotional support in creative works. Such readings are neither comprehensive nor curative, but they make life easier for those who need them (Benson-Allott, 67).

Reparative reading allows Benson-Allott to understand the Girlhood films in their full complexity. She notes that for all its capacity for “feminist joy,” the trilogy “struggles to acknowledge the experiences and insights of women of color” (67). This observation resonates with remarks made by America Ferrara, who plays Gloria in Barbie:

To be perfectly honest, I was never a Barbie girl. I didn’t play with Barbies growing up for a number of reasons. We couldn’t afford them and they just didn’t resonate with me. I didn’t see myself reflected in that world in a way that captured my imagination (Ferrara).

Yet Ferrara goes on to praise the film’s attempt “to challenge and redefine what we consider to be beautiful” and its insistence that beauty is “an inside job”. As Ferrara’s Gloria testifies in her pivotal soliloquy, that interior space is full of existential conflict:

You have to be thin, but not too thin. And you can never say you want to be thin. You have to say you want to be healthy, but also you have to be thin. You have to have money, but you can’t ask for money because that’s crass. You have to be a boss, but you can’t be mean. You have to lead, but you can’t squash other people’s ideas. You’re supposed to love being a mother, but don’t talk about your kids all the damn time. You have to be a career woman but also always be looking out for other people (Barbie, 1:14).

The paranoid position can offer no help with this system of double-binds. There is no singular diagnosis, reduction, or solution to be found. To be a woman, as Gloria declares, is “literally impossible”, yet in this soliloquy, not to be is not an option. Gloria’s version of the doll may be “Irrepressible Thoughts of Death Barbie”, but even as that trope creates the central rupture of the story, the invention implicates her in the extensions of woman. Gloria (if not the woman who acts her) remains a Barbie girl, which is to say, one of those impossible beings called woman. The complexity of this situation is both inescapable and profound.

Coming to consciousness in this Bildungsfilm requires the very different approach offered by Sedgwick. Reparative reading breaks from the hegemonic impulse of strong theory: the “monopolistic program of paranoid knowing systematically disallows any explicit recourse to reparative motives, no sooner to be articulated than subject to methodical uprooting” (144). In place of the monomania of strong theory, Sedgwick offers the radical alternative of “weak theory” (136), which embraces partial knowledge, not absolute certainty, and which is therefore open to contradiction, contingency, irony, and even double binds. This way of knowing has many points of resemblance to that Bergsonian “intuition” espoused by Kember and Zylinska, in whose spirit we began. Under reparative reading, texts and representations need not sum to singular identity. No exclusive explanation is required. Instead, “reparative motives” are “frankly ameliorative:” flights of imagination, visions of alterity, memorable fancies. According to Sedgwick, the paranoid reader will dismiss all these things as “merely aesthetic” or “merely reformist”—both charges that have been leveled against Barbie—but Sedgwick goes on to ask: “What makes pleasure and amelioration so ‘mere?’” (144).

Consider, then, a reparative reading of the Woman on the Bench. We might begin by pushing back against paranoid pareidolia: sometimes a face is just a face. There are other plausible explanations for the cameo casting of Ann Roth. Even assuming that Namesake Barbie is a necessary role—something the paranoid reader asserts without warrant—there could be many reasons the actual Barbara Handler was unavailable, from health challenges to simple lack of interest. Maybe Gerwig turned to her friend as an appealing substitute, seeing the chance to give screen recognition to a cherished creative partner. Perhaps the Woman on the Bench was always intended to be Roth, who may have been from the outset Gerwig’s paragon of timeless beauty. Placed in these contexts, the bait-and-switch scenario begins to look foolish indeed.

There are multiple ways to tell the story of the Woman on the Bench. Forced to choose, this sentimentalist prefers the friendship angle; but reading reparatively obviates that choice. The reparative reader may opt instead for an unresolved range of possible meanings, a cloud or field of signification. The cameo might be left open for debate, defying any need to associate the Woman on the Bench with a human namesake, let alone some sinister doubling. Following this impulse, we might evert the strong theory of replacement into a more generous “weak” scheme. Assuming for the sake of argument that the Woman on the Bench might be Namesake Barbie, then casting someone other than Ruth Handler demonstrates that any woman can be Barbie—or to invoke a deliberate pun, anyone can play Barbie. Taking that verb in the ludic rather than dramatic sense means that any person (girl, boy, or otherwise) can engage in the effigy’s articulated fantasy. The doll’s extension of woman, her version of the human outside the human, is open to all. This transformation brings us to the core work of reparative reading: restoring the possibility of expressive or transgressive play, which is foreclosed by paranoid regimes. In this sense Weird Barbie, who has her origin in such play—and who declares half-audibly the love that cannot speak its name for general audiences12—might be another plausible protagonist for the film, if that is how one chooses to play Barbie.

[6] Love is strange

Swinging with etymological disregard from play to ply, we might come back again to the business of cinematic folding, to see if Benson-Allott’s approach to Barbie offers any help with the main problems of this essay. Consider a reparative reading of autolography and AI art, including my portraits of Claire Tourneur. Here again, Sedgwick is essential. What we can learn from reparative reading practices, she writes, are “the many ways selves and communities succeed in extracting sustenance from the objects of a culture—even of a culture whose avowed desire has often been not to sustain them” (Sedgwick, 151). Does the weak-theoretic lesson of Gerwig’s cameo, in which we learn to deconstruct a supposed identity puzzle into a playful suspension of certainty, offer constructive insights for “remediated photography?” Does Gerwig’s free-floating signification resonate with my own, anxious pareidolia? Can learning to play Barbies bring illuminate my play with Claires?

Behind these questions is a larger one about the hope for “sustenance” from mysterious, monolithic, unseeing, and oppressive systems. Is there any possibility of peace with the human outside the human? In this respect, we might recall a telling remark Sedgwick makes about Melanie Klein, on whose analytical theory she based her notion of interpretive positions. “Among Klein’s names for the reparative process,” Sedwick notes, “is love” (Sedgwick, 128). Love becomes possible, for Sedgwick and Klein, when the defensive crouch of paranoia yields to the “depressive” acceptance of a world which, though eminently broken, still allows investments of affect. These observations set off another round of questions. Is it possible to lose one’s paranoia about narcissus narcosis, algorithmic alienation, and delusions of post-human presence? To add one final layer to the cinematic mille-feuille, can we stop worrying and love AI? I allude to that other influential post-paranoid, Stanley Kubrick, who pointed out how strange (Merkwürdig) love becomes when crossed with technology.

What would it mean to love this thing that Zylinska names “artificial so-called intelligence” (2020, 23), or to immerse ourselves in what she later calls “a media-dirty world” (2023, 13)? To bring these thoughts as close as they may come to closure, I will suggest two insights. The first requires a concession, though never a settlement, in the problematic shift of “outside” from ecology to technology. The concern for the earth and its resources can never be abandoned in any critique of automation, certainly not in the case of AI, with its voracious demands for electricity, water, and minerals. We cannot overlook the “pollution crimes” of this century. Likewise, the race and class biases of the condensed archive, while perhaps more amenable to reform, cannot be excused. It will never be easy to love AI. Perhaps, to paraphrase Gerwig’s Gloria, it will always be “impossible”—or in any case, strange.

This will not be like learning to love the Bomb. Language models and image generators directly implicate culture in ways nuclear weapons arguably did not—setting aside Derrida’s view of the Bomb as “fabulously textual” (Derrida et al.). The first requirement for a strange love of AI is to recognize that it is not a robotic recreation of mind, but as Ippolito teaches, the massive compression and articulation of a global archive (Ippolito). AI thus remains fundamentally a system of signs. Its verbal and graphic productions depend on marvelous and mysterious processes of automation, but they are products of language all the same. Which is to say, the human outside the human is never more than human, at least in origin. If these systems extend man and woman only in some ways to the exclusion of others, the fault lies in our historical and institutionalized selves (though in my case “our stars” has a certain ironic resonance). The productions of AI may dazzle, delight, confound, or devolve into mindless kitsch, but they are at root arrangements of capta derived from human expression. AI-driven art, as Zylinska says, remains attached to human culture (2020, 65).13

Asserting such radical humanism can never excuse the manifold ways algorithmic media fail to sustain us, threatening our dignity and our right to a viable future. Whether they are called Mattel or Meta, oligarchies are concerned for our welfare only if consistent with ownership interests. How do we go on with this knowledge? A paranoid reader can declaim and expose the dire truth, to whatever limited and limiting end, but a reparative operator refuses to grant to hegemons the most important grounds of extended humanity: the faculties of imagination and play. This understanding might allow us to revise the way we regard the pareidolia and apophenia that have been our subjects here. Instead of thinking of these moments as follies of interpretation, cognitive collapses or pratfalls, we might instead see these imputations of presence as acts of delight, and indeed of love. Zylinska orients her later book “toward activating the radical-critical potential of the distributed and embodied perception machine. To put it in more figurative terms, it is about photographing ourselves a better future —for human and non-human ‘us’” (2023, 15). This essay is a much less radical project, but it strives toward that same difficult optimism.

I do not need to believe that some more-than-human overmind brought me that intriguingly metaleptic selfie or the weirdly compelling life series of Claire Tourneur. I can attribute these products to the articulated archive and its invocational interface, both of which I insistently identify with human culture. They came from the model, and the model was built on patterns and tendencies that emerge from very large (though by no means universal) repositories of expression. To be sure, they are also partly MADE UP IN MY MIND, as McDaid says, but I can delight in my play with these expressive media without McLuhanite fears of self-amputation, because I understand the human outside the human not in terms of “outrageous mechanism”, but as fantastic, delirious utterance.

Image generators may be strange, intriguing, seductive, and no doubt in urgent need of critique. Even as we bring them invocations, we cannot imagine them as gods. If we mythologize at all, let them be demiurges— lesser creative agents without omniscience or infallibility. The demiurge can only make a broken world. It is prone to mistakes—or as the language of machine learning calls them, hallucinations (see Ji). This brings me to my last insight for a positive approach to AI: love the mechanism for its limits and its glorious capacity for breakdown. Cherish and celebrate its failures.14

Decades ago, long before the present mania for language models began, the computer scientists Terry Winograd and Fernando Flores wrote a book about software design whose insights feel as indispensable for this moment as the overlooked lessons of ELIZA (fittingly, the cover features an endorsement from Weizenbaum). Folding the project of cognitive computing onto Heideggerian phenomenology, Winograd and Flores speak of “breakdowns”, moments when software tools fail to function as seamless replacements for human understanding and reveal themselves as the limited contrivances they have always been. They write:

There is an error in assuming that success will follow the path of artificial intelligence. The key to design lies in understanding the readiness-to-hand of the tools being built, and in anticipating the breakdowns that will occur in their use. A system that provides a limited imitation of human faculties will intrude with apparently irregular and incomprehensible breakdowns. On the other hand, we can create tools that are designed to make the maximal use of human perception and understanding without projecting human capacities onto the computer (Winograd and Flores, 137).

Reading recent accounts of artificial intelligence in the popular press (see for egregious example, Roose) demonstrates how badly our era has forgotten Winograd and Flores’ warnings against anthropomorphism. I suppose this was inevitable. We do love our machines, sometimes far too literally, and yet breakdowns continue to happen, apparently with increasing frequency as the sophistication of systems increases (Metz and Weise). Consider this evidence from my own practice:

That rusty saw, the poor workman blames his tools, has no force for autolography. The co-creator celebrates the tool, even and perhaps especially when it does not answer the given purpose. Part of a loving disposition toward AI, I suggest, is remembering that language and image models are ever and always implements, subject to surprises and disappointments in which they become perceptible for what they are, “ready-to-hand” in the phenomenological sense. Sometimes these breakdowns are visibly erroneous: too many limbs on a dancer, the persistent problem of six-fingered hands, or the more disastrous surrealism of Figure 10, above. There may be more positive forms of breakdown as well, moments when the system exceeds the literal terms of an invocation. Near the end of her chapter on reparative reading, Sedgwick brings up a colloquy with a friend about another kind of reading-against-the-grain, “reading queer”. Her correspondent, Joseph Litvak, asks: “Doesn’t reading queer mean learning, among other things, that mistakes can be good rather than bad surprises?” (Sedgwick*,* 147).

There’s no surprise more lovely than the apparition of a face.

Works Cited

Abrams, Rachel. “Barbie Adds Curvy and Tall to Body Shapes.” New York Times, January 29, 2016, B1.

Barbie. Dir. Greta Gerwig. Warner Brothers, 2023.

Barnes, Brooks. “‘Barbie’ Reaches $1 Billion at the Box Office, Studio Says.” New York Times, August 6, 2023, C4.

Barthes, Roland. Mythologies. Trans. Annette Lavers*.* Hill and Wang, 1972.

Bender, Emily M., Timnit Gebru, Angelina McMillan-Major, and Shmargaret Smitchell. “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?🦜.” Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency. 2021, pp. 610-23.

Benson-Allott, Caetlin. “Greta Gerwig’s Girlhood Trilogy.” Film Quarterly 77(2) [2023]. 67-72.

Berry, David M. & Mark C. Marino. “Reading ELIZA: Critical Code Studies in Action.” Electronic Book Review, November 2024. https://electronicbookreview.com/publications/reading-eliza-critical-code-studies-in-action/

Bertram, Lillian-Yvonne. A Black Story May Contain Sensitive Content. New Michigan Press, 2024.

Cayley, John. “Literature.” Political Concepts: A Critical Lexicon. (2012) https://www.politicalconcepts.org/literature-john-cayley/

Chesher, C. Invocational Media: Reconceptualising the Computer. Bloomsbury, 2024.

Chesher, C. and C. Albarrán-Torres. “The Emergence of Autolography: The ‘Magical’ Invocation of Images from Text through AI.” Media International Australia. August 2023. 1-17.

Cottom, Tressie McMillan. “The Tech Fantasy that Powers AI is Running on Fumes.” New York Times, March 3, 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/03/29/opinion/ai-tech-innovation.html

Derrida, Jacques, Catherine Porter, and Philip Lewis. “No Apocalypse, Not Now (full speed ahead, seven missiles, seven missives).” Diacritics, vol. 14, no. 2, 1984, pp. 20-31.

Gillis, Stacy, and Chiara Pellegrini. “‘In pink, goes with everything’: the cultural politics of Greta Gerwig’s Barbie.” Feminist Theory, vol. 25, no. 4, 2024, pp. 495-501.

Ferrara, America. “To be perfectly honest, I was never a Barbie girl.” Instagram, November 16, 2023. https://www.instagram.com/p/CzuIpz0SJ32/

Gupta, Anuj, et al. “Assistant, Parrot, or Colonizing Loudspeaker? ChatGPT Metaphors for Developing Critical AI Literacies.” Open Praxis, vol. 16, no. 1, 2024, pp. 37-53.

Hofstadter, Douglas. Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid. Basic Books, 1979.

Ippolito, Jon. “Honey, AI Shrunk the Archive: Artificial Intelligence as Compression Algorithm.” Pre-publication draft. https://jonippolito.net/writing/ippolito_ai_as_compression_v2.1.pdf.

Ji, Ziwei, et al. “Survey of Hallucination in Natural Language Generation.” ACM Computing Surveys, vol. 55, no. 12, 2023, pp. 1-38.

Johnson, G. Allen. “Revisiting Wim Wenders’ Grand Vision, ‘Until the End of the World.’” San Francisco Chronicle Datebook. March 20, 2020. Online. https://datebook.sfchronicle.com/movies-tv/revisiting-wim-wenders-grand-vision-until-the-end-of-the-world.

Juul, Jesper. Half-Real: Video Games Between Real Rules and Fictional Worlds. MIT Press, 2005.

Kember, Sarah, and Joanna Zylinska. Life After New Media: Mediation as a Vital Process. MIT Press, 2014.

Kirschenbaum, Matthew. “Prepare for the Textpocalypse.” The Atlantic, March 8, 2023. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2023/03/ai-chatgpt-writing-language-models/673318/.

McDaid, John G. “Coaxing the Impossible (a short, academic fiction).” Medium April 11, 2024. medium.com/@jmcdaid/coaxing-the-impossible-a-short-academic-fiction-62dec90c1374.

McLuhan, H. Marshall. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. MIT Press, 1994 [1964].

Metz, Cade, and Karen Weise. “AI is Getting More Powerful but Its Hallucinations are Getting Worse.” New York Times, May 5, 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/05/05/technology/ai-hallucinations-chatgpt-google.html

Moulthrop, Stuart and Stable Diffusion. Unstable Confusion. 2023 and continuing. www.smoulthrop.com/dev/unstable.

Noble, Safiya. Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. New York University Press, 2018.

Pynchon, Thomas. The Crying of Lot 49. Little Brown, 1966.

---. Gravity’s Rainbow. Viking, 1973.

Rogers, Johanna. Message to the audience. ELO (Un)linked 2024. 21 July 2024.

Roose, Kevin. “A Conversation with Bing’s Chatbot Left Me Deeply Unsettled.” New York Times, Feburary 16, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/16/technology/bing-chatbot-microsoft-chatgpt.html.

Schull, Natasha D. Addiction by Design: Machine Gambling in Las Vegas. Princeton University Press, 2012.

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity. Duke University Press, 2002.

Stable Diffusion. Prompt Database. Online : https://stablediffusionweb.com/prompts.

Stoppard, Tom. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead. Grove Press, 50th Anniversary Edition, 2017.

Turkle, Sherry. Life on the Screen: Identity in the Age of the Internet. Simon and Schuster, 1995.

Tyka, Mike. “Portraits of Imaginary Persons.” Mtyka.github.io. 20 October 2023. https://mtyka.github.io/machine/learning/2017/06/06/highres-gan-faces.html.

Wardrip-Fruin, Noah. Expressive Processing: Digital Fictions, Computer Games, and Software Studies. MIT Press, 2009.

Weizenbaum, Joseph. Computer Power and Human Reason: From Judgment to Calculation. W.H. Freeman, 1976.

Wenders, Wim. Until the End of the World. Warner Brothers, 1991.

Winograd, Terry, and Fernando Flores. Understanding Computers and Cognition: A New Foundation for Design. 1986.

Young, Neil. “Motion Pictures (for Carrie).” Reprise, 1974.

Zylinska, Joanna. AI Art: Machine Dreams and Warped Visions. Open Humanities Press, 2020.

---. The Perception Machine: Our Photographic Future between the Eye and AI. MIT Press, 2023.

Footnotes

-

Technically speaking, hallucination of faces is a special case of apophenia called pareidolia. As not all the illusions discussed in this essay involve faces, I will alternate these terms depending on context. Thanks to my brother, Andrew Moulthrop, for reminding me of this distinction. ↩

-

An early, partial draft of this essay was presented at the 2024 Electronic Literature Organization conference. The current version has been considerably revised and expanded. ↩

-

The degree zero in this case is an empty prompt, which the interface I was using allowed, unlike some other systems. Results of this procedure have been various, usually converging on abstract expressionism, or lately, science fiction cover art from the 1970s. This may be because my repeated use of the system has established these styles as favorites, even though an empty prompt makes no specific invocation—“our desires and their fulfillment,” as Zylinska says. ↩

-

The ableist limitations of this project will be obvious. It has been instructive to discuss this work with a friend whose neurotype includes “face blindness”—a reminder that the categories and experiences on which I speculate are far from universal. This essay concerns one set of constructions for “human outside the human,” but that set is neither exclusive nor exhaustive. ↩

-

This claim may be easier to accept if you are closer in age to the last Claire than the first, because you may have seen similar things in the mirror. As an acid test, I presented my unified-Claires theory to two sets of graduate students, each with a healthy record of skepticism about my interpretations. They did not reject the notion out of hand, though they did remind me of its subjectivity. ↩

-

Or as certain lab-coated presences in Gravity’s Rainbow say to their narcotized subject, “Snap to, Slothrop.” (Pynchon 1973, 61). ↩

-

See Anuj Gupta, et al., “Assistant, Parrot, or Colonizing Loudspeaker? ChatGPT Metaphors for Developing Critical AI Literacies.” The article notes important limits of the parrot metaphor, among others. ↩

-

The cross-media enfoldings in this essay may be compared to Zylinska’s AUTO-FOTO-KINO, mentioned earlier. Using a Generative Adversarial Network, Zylinksa reprocessed the still images that make up La Jetée into a new cinematic composition. She describes the work as an attempt to “redream” Marker’s film. My Claire series might also be understood as re-dreaming. ↩

-

Young’s headlines belonged to Watergate—the album cover features a newspaper blaring a call for Nixon to resign. The headlines of 2023-25 are perhaps less stultifying than horrifying, but the perniciousness of the doomscroll remains. ↩

-

Barbie’s body shape remained uniform until 2016, at which point “Curvy” and “Tall” variants were added—see Abrams. ↩

-

Early releases of Barbie contained a continuity error in this scene, with some shots taking place in an enclosed bus stop and others on an open bench. The error has been corrected in later releases. The fact that Gerwig kept the scene despite visual flaws underscores its importance, which she has mentioned in interviews. ↩

-

At 0:23:29, having introduced Stereotypical Barbie to Birkenstocks, Weird Barbie declares her love for the heroine, but can only speak sotto voce. We might say the character’s rightful name is Queer Barbie. Such unmasking is no doubt paranoid, but sometimes that mode is inevitable. Along with the Stereotypical paragon, Weird Barbie is the only variant not named for her profession. She is the only doll whose identity arises from transgressive play — though Mattel has now brought her to market like any other pre-distressed commodity. ↩

-

Admittedly, this claim may be precarious. Developers have already reported exhausting the stock of internet-accessible text used to train language models and are training new models on the output of old. (What could possibly go wrong?) See Cottom and also Kirschenbaum on the likelihood that generated text will overwhelm human-created language. Assuming the inevitable apocalypse is more Wenders than Kubrick—correction rather than extinction, like the fate of the internet after the dot-com blowout—then perhaps the recognition of AI’s human roots may prove not just relevant but potentially restorative. ↩

-

Zylinska makes a similar point in her discussion of “AUTO-FOTO-KINO,” where she exploits the limitations of more primitive generative systems as foundation of her intervention (2023, 143). ↩

Cite this article

Moulthrop, Stuart. "Parrots on a Wet, Black Bough: Facing into AI Art" Electronic Book Review, 18 January 2026, https://electronicbookreview.com/publications/parrots-on-a-wet-black-bough/