Collaborative Reading Praxis

Marino, Douglass, and Pressman describe their award-winning collaborative project, Reading Project: A Collaborative Analysis of William Poundstone’s Project for Tachistoscope {Bottomless Pit} (2015). Given the novelty of Poundstone’s work and its deviation from traditional forms of print-based literature, the authors break down the methods and platforms that allowed them to respond with new ways of reading—what they call “close reading (reimagined).” Indeed, their respective methods of interpreting Poundstone reminds that the field of e-literature not only brings new literary forms to our critical attention, but also necessitates that hermeneutics adapt to digital contexts as well.

Reading Project was awarded the ELO’s 2016 N. Katherine Hayles Award for Literary Criticism on Electronic Literature.

Our reading project is a digital humanities effort in that it is a collaboration that employs digital computing practices in order to analyze a text from the perspective of humanistic hermeneutics…. Our intervention in this book is to show how digital-based practices can enable literary interpretation while also providing new models of how interpersonal collaboration works.

— Pressman, Marino, and Douglass, Reading Project 137

In 2009, we three scholars embarked on a collaborative reading of a single work of literature. One text, three readers. The work is a piece of electronic literature that combined a one-word-at-a-time story with flashing images, bursts of music, and additional surprises. The work was fast and noisy and challenging to anyone schooled in reading static text on the page. Its audacity and disruptiveness seemed to epitomize the disruption of digital culture itself on the slow, meditative experience of reading that beats at the heart of traditional humanities scholarship. What we needed was to prevent our attention from dissipating with the disruption. What we needed were new ways of reading, drawing upon and contributing to the burgeoning practices of the digital humanities.

Reading is a practice that is typically as solitary as the individual names on the scholarly monographs that perform it. And yet with digital literature, the object of art has become much more complex. Or should we say, with the digital object of art, the complexities are often foregrounded and the number of artistic practices applied to its construction proliferate. To thoroughly understand these complex assemblages is more than one individual — especially one trained to specialize within academic disciplines — can typically muster. Therefore, we knew early on that we would need each other to develop a rich and full reading, that if we were to attend to the nuances and range of levels on which this object communicated, we would need backup. In fact, in our early discussions we decided that our collaborative undertaking would be a good opportunity to disrupt the myth of the solitary scholar. However, what we did not realize was that as we explored that single work as a team, we were developing a collaborative practice that would epitomize the kinds of critical practices necessary and crucial for inquiry in the digital humanities at this moment of crisis.

Much has been made of and debated about a “crisis in the humanities.” To be clear, by “crisis” we do not mean some threat to the humanities based on a decline, real or perceived, of students choosing to major in the humanities. This is not a financial crisis, but rather a crisis of faith. As Alan Liu explains, “The general crisis is that humanistic meaning, with its residual yearnings for spirit, humanity, and self — or, as we now say, identity and subjectivity — must compete in the world system with social, economic, science-engineering, work-place, and popular-culture knowledges that do not necessarily value meaning or, even more threatening, value meaning but frame it systematically in ways that alienate or co-opt humanistic meaning” (419). Our reading project would ultimately embrace the tools and methods of scientific inquiry but only to set them to them most traditional and fundamental of humanities activities, reading — including all reading entails, such as the pursuit of meaning, the exploration of aesthetics, and even the experience of pleasure — with others (or more specifically, friends).

Our Background

Project for Tachistoscope {Bottomless Pit} by William Poundstone is a celebrated work of electronic literature anthologized and taught in courses on digital literature. However, it is marked by an aggressive inscrutability. The work presents the story of a pit which is unfathomable, both figuratively and literally. To access that story, a reader must parse the fast-flashing one-word-at-a-time text, while being bombarded with flashing icons and shrill runs of music. In fact, the text was so challenging, two of us were reluctant to investigate it. Jessica, who had written on the piece before, assured us that it was worth our time, and our mutual investigation began. The question remained: how could we read such a work that defied reading itself? That was when we turned to our tools.

In our separate scholarship, we had been developing techniques for scholarship that were not focused on reading in the traditional sense.

Jessica had been pioneering strategies for close reading digital literature, with special emphasis on works that took a modernist literary aesthetic into the electronic realm. In her book, Digital Modernism, Jessica models reading practices that slow down fast media for scrutiny and exegesis. Her reading practices were traditional in the sense that they involved deep dives into bibliographic sources yet at the same time quite novel because her objects of study were profoundly different from codex books. One of her objects of study in that book is Project for Tachistoscope, which led her to want to read it more closely with collaborators..

Jeremy had been developing cultural analytics with Lev Manovich at UC San Diego. This method of analysis uses very large computer monitors in order to do visual analyses of large bodies of work, for example, every cover of Time Magazine. During that exploration, Douglass developed additional techniques for adapting software to the visual analysis of content, specifically video. These tools would prove quite helpful when used to analyze a time-based work of electronic literature.

Mark had been working in collaboration with Jeremy on developing the initial practices of critical code studies, the application of hermeneutics from the humanities to the interpretation of the extra-functional significance of computer source code. That practice involved examining source code as a cultural text in order to discuss its cultural meaning. He models these methods in his new book Critical Code Studies.

Together we three scholars set out to read a work of digital literature together using the methods we had been developing separately. The result was a collaborative reading experience that changed the way we saw the digital object individually and in many ways changed the way we thought about scholarship in the digital humanities. However, the result was also a surprising intervention in digital humanities scholarship— an example of reading digital literature AS digital humanities methodology.

However, our collective reading did not emerge merely from our own trio but rather grew in the fertile ground of academic conferences. The idea for reading project for Tachistoscope began at the 2009 Digital Arts and Culture conference. It was there that we decided to try to read something together in a proposal for the upcoming 2010 conference of the Electronic Literature Organization at Brown University. At the Brown conference, Dee Morris saw our talk and invited us to turn it into a book proposal for Iowa Press. These communities within the digital humanities provided not just the opportunities to present the ideas but the gatherings of the communities of practice that would inspire and motivate our work together. Digital Humanities happens together.

Our Object of Study

Project for Tachistoscope {Bottomless Pit} is a flash-based work of electronic literature. At its core, the piece tells the story of a mysterious bottomless pit that has opened near a town. The people of the town have been trying to understand it, measure its depths, determine its origin, to no avail. As mentioned, this work flashes the tale one word at a time during the animated sequence. However, the words offer only a very small element of this piece, for while these words are flashing, the piece plays random sequences of additional images and sounds that make the attempt to read the piece difficult if not impossible. On top of that, occasionally, additional words flash at a rate that is too fast for the most to read, let alone perceive. The whole story plays out in about three minutes.

Our Methods

In her essay “Where is Methodology in Digital Humanities,” Tanya Clement situates reading as “only one among many hermeneutical methods for thinking through the formation of culture”(163). However, we situate reading not as one practice but as many interoperating practices that include critical making, cultural analytics, media archaeology, critical code studies, and many other practices. Furthermore, the nature of this story cannot be fully observed without the use of unconventional and machine-assisted reading methods. Even that last observation, the length of the story, only became clear once we employed additional reading tools and strategies. In fact, like Heidegger’s formulation of the watermill that calls forth power from the river, Project called forth reading methods from its critics. However, these reading methods do not merely apply to digital literature; they can be applied to objects across the digital humanities.

Close Reading (reimagined)

The digital humanities have radically transformed inquiry. Software and hardware have transformed the way we read, giving scholars the ability to perform what is known as “distant reading,” which entails examining not a single work, but a huge corpus of works, for example, every novel written in the nineteenth century. Scholars like Franco Moretti and Lev Manovich have shown what it means to turn an entire corpus into the object of study. How radical, then, in this age of large-scale examination to turn one’s attention to a single work. That is exactly what our project did, employing an older practice of close-reading, a practice that grew to prominence in the early part of the Twentieth Century. The idea was to examine the text completely as a kind of self-contained world of meaning, attending to its signifying practices in as much as they spoke back to the object itself. However, close reading, especially under the New Critics developed over time a rather poor reputation. The practice in time developed a reputation for being a kind of apolitical reading, eschewing interpretative practices that referred to the political times. Close reading was seen as a safe reading practice of the McCarthy Era, providing scholars with protection against accusations of politicizing reading.

Whether or not close reading deserved this reputation, close-reading could never be “closed” reading after post-structuralism and after the innovations and developments of feminisms, queer theory, critical race theory, and other critical reading practices which grew out of the second half of the Twentieth Century. At the same time a contemporary closed reading developed an understanding of the internal structures of a piece, it would also have to be guided by sensitivities to the political and ideological undercurrents that shaped the meaning of the work.

At the same time, in the digital realm, close reading would also mean much more than merely reading words. Reading digital objects closely requires the application of methods specific to their nature. So says the notion of “media specific analysis” promoted by N. Katherine Hayles (Hayles and Burdick 2002) and Lev Manovich (2002). Since so many objects in the humanities are now digital, these same tools and methods can be applied more broadly across the humanities. However, to close read a fast-flashing work of digital literature, scholars need to find a way to slow it down. Jason Farman (2018) has argued for the importance of delay and slowness in the communication transmission, and yet here was a work that seemed to have none of that. Our work of literature appeared to be running away from us. We needed to find ways to slow it down for closer inspection.

Digital objects are made of code, and software objects offer source code, which is accessible to varying degrees. The code of objects such as webpages can often be easily accessed merely through the “View Source” option. However, in the case of other objects, the code is often obfuscated or rendered unreadable by the software itself. Such is the case with our Project.

Visualization

One of the key methodologies developed in cultural analytics has been the application of visualization software to the analysis and exploration of digital objects. Having worked in the development of these techniques, Jeremy saw great potential in applying them to the reading of this complex work. SinceProject is such a fast-flashing visual work, Jeremy decided that it would be useful to slow it down.

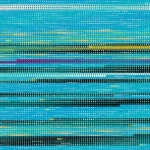

One of his first techniques involved creating a video recording of a play through of the piece. Once recorded, Jeremy created an object he called the “montage” view, taking screen captures of the piece at set intervals and then laying them out sequentially in lines, so they can be “read” from left to right, top to bottom. The image he created, a 4MB grid, became one of the most iconic images of our inquiry, even appearing on the cover of our book. In one chapter, Jessica recounts her shock the first time she saw this image, for it allowed her, for the first time, to read the video as she would a sentence. The screenshots offered us not only a sense of how long a play through lasted, since we could see when it looped around to the first word of the story again, but it also gave us our first captured record of what we were calling the subliminal words, the words that were flashing in between the story words.

Another visualization technique Jeremy had developed through cultural analytics involved turning a video into a three-dimensional object and then applying the same software used to analyze 3-d brain scans. To understand this technique, imagine taking all of the screen shots from the montage view and stacking them up, one upon the other, to create a three dimensional block. Once in this form, that block, which is essentially another representation of the screen’s changing state over time, can be sliced horizontally to examine one plane or axis as it changes over time. The edges of this block also reveal more clearly how long the background color changes, as one can compare the width of those sections with the whole. Also, by turning the background image transparent, Jeremy could produce an image of the piece that looked like a tunnel, with its sides sometimes widening, sometimes shrinking. Here, at the center of the visual display of Project for Tachistoscope, largely invisible to the person merely staring at the flashing playthrough, was a visual representation of the pit in this tale about a bottomless one.

While these screenshots can be stretched into three dimensions, they can also be flattened into a two-dimensional image. Imagine, all of the screenshots as hair-thin (or thinner) acetate sheets, stacked up, so that one can look through an entire screenshot at once. Now by applying various transformations, the scholar can investigate patterns. For example, the changes to that center hole over time.This view also reinforces an understanding that Poundstone’s design draws the eye’s attention to the center of the screen, while the edges remain far less used, encouraging our tunnel vision as we descend into the pit of the piece. Through these visual processes we were able to see what we were seeing when reading Project.

Material History

Along with our attempts to see Project more fully, we also wanted to understand the technologies both used to build the piece and represented in it. To that end, we turned to a key practice in digital humanities called Media Archaeology. Media Archaeology names a branch of study that attends to the material history of an object, examining not just its technological nuances but also the historical context of its creation and use. In the case of Project, we had at least two technologies to examine: Flash, the medium of the story itself, and the tachistoscope, which turned out to be not one type of object, but a class of objects used to display images or text at very fast speeds (hence the root word tachi, the Greek word for fast). While the history of Flash led us to read the work against its use, primarily in the late-90s Internet, particularly in web advertisements, our investigations into the tachistoscope, the medium that was being remediated (Bolter and Grusin), splayed our investigation into many additional directions. As Jessica took a deep dive into a patent search, she found the number of its uses multiplied, from speed reading tests to combat training.

The exploration of Poundstone’s piece also relied heavily on Jessica’s explorations of several strands of cultural history. Using scholarly databases and good old fashioned books, Jessica took deep dives into the histories of advertising, subliminal messaging, and most significantly for our exploration, spam. Spam, that class of unwanted messages, proved to be central to Project, and Jessica’s investigation of the history of spam took her back to the beginnings of the postal system in the United States. However, Jessica’s explorations of history were never merely about gathering facts but instead about exploring cultural constructions that would inform the meaning of this larger piece. In other words, to look for the origins of spam is to ask what is spam, a question that leads both into other media (like printed mail circulars) as well as fundamental aspects of communication, such as signal and noise.

Media Forensics

In addition to studying the classes of media (Flash and various tachistoscopes), we also found ourselves needing to access the object itself, in this case an SWF file, which is a media object package designed to deliver Flash on the Internet. However, reading a Flash object is a bit harder than reading the code of a web page that can be displayed merely by clicking View Source. In fact, this obfuscation of assets was one of the selling points of Flash, which has since fallen in disrepute and is no longer being supported on most browsers. 1 In order to analyze the SWF file, we would need to decompile it. 2 By decompiling the SWF we can access a recreation of the source file for the piece. With that, the piece opened up even further.

Code Studies

A chief component of our reading, especially given Marks’ interests, was an exploration of the source code of the project. For over a decade, Mark has been working with Jeremy and others to develop the methods of Critical Code Studies, a practice of interpreting the meaning of computer source code (Marino 2006, 2020). Actually, in many ways, this exploration should come first, for not only was it instrumental in informing our overall knowledge of the piece itself, it also led to a key determinant for whether or not we would study the piece at all. Prior to looking at the code and source files, our group was split on whether or not to explore this piece. Jessica had spent quite a bit of time with it, but Mark and Jeremy were relative newbies, and Mark admitted that the words were flashing faster than he could take them in. However, as our team set about examining the artwork as a piece of software, we came across a file that transformed our opinions and drew us into an enthusiastic exploration of this digital literary work. That was the discovery of the bp.txt file. This file, which is loaded by the SWF file and is archived in the ELD vol. 1, contains the entire story and all of the flashing interruptive words in plain text. In other words, having discovered this file, we could now read the story as we might any print-based text story. Once we could read this story, we could slow down this very fast work and meditate on it, using the traditional tools of textual analysis. While in most explorations, the code reading is secondary, revealing discoveries that illuminate our reading, this code reading was primary for it enabled the initial reading of the work, or at least of the story component.

Also, once we had access to the ActionScript code, through the decompiling process and later the source files from Poundstone, we could more fully understand exactly how the piece worked, the operations that made all those effects that Jeremy had captured through his visualization techniques. The code, however, did more than confirm or contradict suspicions about how the work was operating. The code also revealed to us hard-to-perceive aspects of the nature of the piece, for example, that it is a call from the code to the subliminal function that then brings the story words to the surface. While the surface experience suggested that the story words were primary, the code suggested it was the subliminal content that called forth the story. Our most notable discovery was perhaps the fact that these subliminal words (as they had been framed in the paratexts) were also referred to in the piece as spam. Spam, that scourge of digital communication, that clutter that fills our email inboxes, and all its techniques for getting through filters, including incorporating unrelated words such as those in Poundstone’s list, was infiltrating the reading experience for those who encountered the Bottomless Pit, that was both a diagetical mysterious story element and a name for the screen itself.

Textual Analysis

Along with visual analytical tools, cultural analytics also gave us digital analysis tools for dealing with text. Once we had discovered these spam words inside the text, the question remained, what do they represent? What do they have in common? That led Jeremy to perform some computational analysis on the words themselves, a search that led him to conclude that each word on the list had very little to do with each other, whether in its form or its meaning. Ultimately, we would conclude that the governing principle for selecting the words must have been dissimilarity. Like the words appended to a spam message to help it pass undetected through spam filters, these words would defy pattern and comparison. Unlike the very conventional textual pattern of the story, these words defied pattern recognition.

It would be disappointing if “textual analysis” in a chapter about reading digital literature was reduced to only “the computational analysis of text.” Reading is the chief end of our project and, we argue, the larger literary project within humanistic inquiry. Computational textual analysis and all of these other tools are merely approaches to reading, tools and techniques for reading, and this is where we offer our argument that the study of electronic literature offers a useful model and perhaps even necessary corrective for the digital humanities. Many of these methods we employed, because they make use of computational processes, serve the pragmatic deployment of “digital humanities,” or the “tactical” usage that Matt Kirschenbaum has identified, in the pursuit of funding and institutional support and recognition. Indeed, we have benefited from grants and other awards supporting our use of digital apparati in these environs.

However, the resulting assets, the processes, the technologies are not the ends, not our goal, but rather the enriched understanding of a digital text and through it a deeper understanding of our word. Computer-based methodologies and technologies may please funding agencies and delight deans, but what the humanities offer are the joys and journeys, the challenges and puzzles, of ephemeral and incalculable humanistic (and post-humanistic) experiences of works of art encountered, in our case study, with and through collaborators. When we lose sight of those goals, we have instrumentalized humanistic inquiry to death.

Combined Methods

Because of that simple fact, our reading project, and we argue the process of reading digital objects more broadly, requires and benefits from the combination of techniques and perspectives. Collaborative reading in the digital humanities is not merely an attempt to document what is there but a creative enterprise to produce new meaning and ways of understanding. Beyond the myth of the monograph, we offer collective reading as a model of inquiry in the Digital Humanities not simply because it yielded such impressive results for us but because such a methodology is more suited to these complex digital objects. Digital reading processes are not product-oriented; they are dialogic, they are hermeneutic not in the sense of discovering the secret but in the fuller sense of opening up a text to multiple imaginations in conversation. Jessica’s discoveries of patents informed the way Mark analyzed the code as a kind of tachistoscope. Mark’s discoveries in the code informed the way Jeremy perceived his visualizations. Jeremy’s discoveries in visualizations changed the way Jessica understood the story. Which is not to create some image of a unidirectional process in which one’s discoveries illuminated one other person. All of our discoveries informed our shared exploration and led to more questions and interpretation. But to call these “discoveries” is to mislabel, for we were not so much finding what was hidden in the text as interacting with the text through reading processes to create new understandings of Project and in many ways new versions of the piece through collective inquiry, discussion, exploration, and experimentation.

Our Platforms

Reading collaboratively requires some coordination. To facilitate our reading practice, we required platforms, just as a means to exchange messages and compare notes, but a place to post our discoveries, which often took the form of artifacts, including patents, images, audio, and even code files. Our chief repository ended up being a Google Drive, cloud storage space, where we could not only share live drafts of the text but could also organize the various assets we collected. Jeremy was chiefly tasked with keeping those files straight, so that we could easily find these tools of reading. However, we would be remiss to downplay the centrality of Google Docs. Not only did the collaborative writing environment give us an easy way to see each other’s edits, but also transformed our collaborative text into the meeting space for our mutual effort. The Google Doc became the coffee shop, clubhouse, meeting space.

However, our Google Drive was primarily a storage platform. What we needed was a way to incorporate these assets into our argument. As we scanned the horizon we discovered ANVC Scalar, a platform for multi-threaded multimedia scholarship. Here was a platform that allowed us not merely to reference multimedia assets, as we began calling them, but to incorporate them into our argument. A brief aside about Scalar will be useful here.

An author in Scalar creates a series of pages and then links them together in what the system refers to as paths. Any given page can be on any path, and this does not even begin to open up the additional levels of possibility afforded by features such as the ability to add annotations. For now, let us stay with the simplest explanation. Each multimedia asset (video, audio, image, code) can be embedded in any page. However, and here is when the platform becomes truly transformative, those assets can also be pages on the path. Imagine a person with a large file folder of materials. The folder contains pages of related content as well as photographs, for example. Now, imagine that person stringing those together, images and text, in order to present an argument. Now, that person uses another piece of string in order to thread together another possible argument, or path through the material. More than merely describing features of a hypertextual document, this description of Scalar emphasizes the ways the media assets become primary to argumentation rather than secondary and in which the path or progression through any group of content (text and assets) renders that set of material meaningful. Compared to a codex book, which primarily offers one path (in addition to targeted access through the index, Scalar offers multiple reading avenues.We would not argue that such affordances do not exist in a typical website, for they could easily be coded, but rather that Scalar foregrounds the creation of multiple paths through text and assets as its core offering. While the main avenues in a town do not determine one’s course through those avenues (e.g., a pedestrian can cross the avenues rather than following them), the avenues determine the flow of much of the traffic.

Scalar transformed our way of thinking about our content. However, there was another feature of our process that we wanted to foreground, collaboration. What made our reading exciting and unlike previous explorations was the way our discoveries informed each other’s reading of the text. We wanted to present that act of collaboration as a principle feature of reading a digital object. At the same time, we did not want to present our work as a one-off reading by a particular team of scholars, a definitive reading. For this reason, in 2013, we set out to build, in collaboration with Lucas Miller, Erik Loyer, and Craig Dietrich, ACLS Workbench, a project funded generously by a Collaborative Research Grant from the American Council of Learned Societies. ACLS Workbench was a fork of Scalar that added to this powerful platform the ability for any scholar to request to collaborate on any book, as Scalar collections are called, and also the ability to clone any book. 3 That meant that someone who was reading a Scalar book, examining all of the threads and content, could copy that book and begin creating their own reading out of the materials. We would not go so far as to say that the assets were the keys to reading but instead that the assets represented the digital material signs of the application of a lens and some non-trivial effort. The goal was not to present the wonderful abilities of those who produced those assets and then separate those from the reading but instead to show how those assets constructed the readings and could equally inspire other ones. Rather than treat these artifacts as part of the production notes for the final argument, Workbench would offer them as fruits of the process and material for future readings. In many ways, these artifacts themselves, perhaps most evident in the visualizations, became new versions of Project for Tachistoscope, that could also be read. The motto was not “show your work,” but “share your work,” so others could build on it or remix it into something else entirely.

Along with Scalar, Workbench, and Google Drive, we also relied heavily on email. These days, productivity-ware has exploded into the consciousness of those who must work in teams via computational media. Software such as Slack and Bootcamp help collaborators to manage complex tasks, as the platform integrates calendars, to-do lists, notes, and drafts. Although we did not use one of these platforms, we essentially had to jerry-rig one, with Jessica primarily at the helm.

The digital object does not, fortunately exist, merely as a text on a shelf. Neither do texts on shelves for that matter. The digital object has often been catalogued electronically, linked not just to related items but to those who have read them. For that reason, our work was indebted to the ELMCIP Knowledge Base, a vast repository of information regarding digital literary works. Now, as a part of the CELL Project, linked to an international set of databases, ELMCIP stands as a tool that can promote discourse by offering context and also the state of the scholarly conversation on a piece. The page for Project for Tachistoscope features not only our scholarship but also the other scholars who have interpreted the piece, along with various versions of the piece. We have the opportunity with digital objects to coordinate scholarship across platforms in ways that were cumbersome and often impossible for print scholarship.

ELMCIP, and its parent database CELL, offer more than merely electronic versions of what were formerly print resources. They signal a change in the nature of humanities scholarship, wherein the development of academic knowledge is proceeding at a pace faster than print, particularly printed books can keep pace. ELMCIP seeks to explore “how creative communities of practitioners form within transnational and transcultural contexts, within a globalised and distributed communications environment. We seek to gain insight into and understanding of the social effects and manifestations of creativity” (Rettberg “Introduction”257). At the same time, through the creation of these databases, humanities knowledge does not become science, rewritten into some progress narrative but remains a site of contest. As the CELL Manifesto explains, “Insofar as literary knowledge by its nature is processual, contingent, and contentious, the study of literature is entirely consistent with current best practices in digital media.” CELL contributions are original content produced in a context of scholarly discourse not empirical discovery. Even in the database, the humanities maintain their humanity.

The Glue, The Engine, The Chief Among Equals

We have gone a long way in this article narrating a course that seems inevitable, as though it were a seamless process. But anyone who has attempted to collaborate with a team on a scholarly project, whether digital or analog, knows better. Coordinating three scholars, keeping this undertaking on track, wrangling the collaborative cats requires a tremendous exertion of energy. While it is easy to present the sexy side of innovative reading practices, someone still needs to do the daily work of keeping the overall project on track. For our book the person who filled that role was Jessica. Engaging in countless hours of emails and phone calls, scheduling meetings and group writing times, and directing drafts and revisions, Jessica was the glue that held us together, the engine that kept our project moving forward, and the chief among equals who guided priorities. Jessica also did the core work of synthesizing all of our various findings into the braided, coherent reading presented in the final book. It is important not to overlook Jessica’s work in this capacity because to do so would be to omit a key to making these collaborative projects happen. Bethany Nowviskie has described a “feminist ethic of care,” a praxis that “seeks … to illuminate the relationships of small components, one to another, within great systems.” To omit the largely unseen labor of keeping the project moving forward would also obscure a crucial element to collaborative scholarship, the need for a producer, someone who is willing to take charge, who can keep the ship on course. Without such a person, projects will often be started but will never reach completion. The collaborative scholarship needs a captain. As our captain, Jessica saw our project through turbulent waters.

Take-Aways for DH

In her essay on “Just Humanities,” Stephanie Boluk warns against the instrumentalization of the humanities, a faulty attempt to make the humanities seem more “productive” by turning away from its core competencies, if we can take yet another term from academic corporate speak, critical analysis and interpretation. Similarly, Alan Liu speaks of a need for “dedicating the digital humanities to the soul of the humanities” (420). We stand with Boluk and Liu in this model of collaborative analysis. Through our case study, we hope to promote a form of computationally enhanced reading rather than computation instead of reading. Rather than letting computational processes become the means and the ends of our inquiry into digital text, we would like to harness computation to enrich and complement our exploration. Many projects in the digital humanities, enframe the work within the digital scaffolding. We encourage scholars to then climb the scaffolding in order to take a closer look at the work.

However, the tools and techniques are only part of the story. As the Alliance for Networked Visual Culture argues, “New technological platforms like Scalar are a key part of the process but equally important are the human networks we are building: rich collaborations between archives, presses, and groups of scholars who can together provide new platforms for scholarship that are motivated by the key questions that animate humanities scholarship.” The platforms that network our scholarship through the digital object are worthless without the networking of scholars in creative and critical collaboration.

Our experience also taught us the fundamental necessity of accepting the collaborative nature of reading in the digital space, even when pursuing objects that are as deeply personal as poems. While we would never attempt to devalue the individual encounter with the work, our exploration taught us that reading thoroughly in the digital realm, due to the complexity of the objects of study, benefits from and is enriched by collaboration in pursuit of the finest fruits of the humanities: wisdom, understanding, and enjoyment.

Bibliography

“Alliance for Networking Visual Culture » About The Alliance.” n.d. The Alliance for Networking Visual Culture. Accessed June 4, 2019. https://scalar.me/anvc/about/.

Bolter, J. David, and Richard Grusin. 1999. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Boluk, Stephanie. 2014. “Just Humanities.” Electronic Book Review, electropoetics, March. http://electronicbookreview.com/essay/just-humanities/.

Burdick, Anne, Johanna Drucker, Peter Lunenfeld, Todd Presner, and Jeffrey Schnapp. 2012. DigitalHumanities_. The MIT Press.

Chun, Wendy Hui Kyong. 2013. “The Dark Side of the Digital Humanities – Part 1.” In Center for 21st Century Studies. Boston, MA, USA: Center for 21st Century Studies. http://www.c21uwm.com/2013/01/09/the-dark-side-of-the-digital-humanities-part-1/.

Douglass, Jeremy. n.d. “Transverse Reading Gallery.” Transverse Reading Gallery. Accessed June 4, 2019. https://jeremydouglass.github.io/transverse-gallery/.

Farman, J. (2018). Delayed response: The art of waiting from the ancient to the instant world. Yale University Press.

Harrell, D. Fox. 2013. Phantasmal Media: An Approach to Imagination, Computation, and Expression. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

Hayles, N. Katherine. 2008. How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics. 1 edition. University of Chicago Press.

Hayles, N. Katherine, and Anne Burdick. 2002. Writing Machines. The MIT Press.

Hayles, N. Katherine, Nick Montfort, Scott Rettberg, and Stephanie Strickland, eds. 2006. Electronic Literature Collection. Vol. 1. Electronic Literature Organization. http://collection.eliterature.org/1/.

Heidegger, Martin. 1977. “The Question Concerning Technology” The Question Concerning Technology, and Other Essays. Harper & Row.

Kirschenbaum. Matthew. 2012. “Digital Humanities As/Is a Tactical Term.” Debates in Digital Humanities. ed. Matthew K. Gold. U. of Minnesota Press.

Lach, Pamella R. and Jessica Pressman, “Digital Infrastructures: People, Place, and Passion, a Case Study of SDSU” in Debates in the Digital Humanities: Institutions, Infrastructures at the Interstices (forthcoming from U Minnesota Press, 2021), eds. Angel David Nieves, Anne McGrail, and Siobhan Senier)

Liu, Alan. 2013. “The Meaning of the Digital Humanities.” PMLA 128 (2): 409–23. https://doi.org/10.1632/pmla.2013.128.2.409.

Marino, Mark C. (2020). Critical Code Studies. The MIT Press.

— (2006). Critical Code Studies. Electronic Book Review. http://www.electronicbookreview.com/thread/electropoetics/codology

— 2018. “Reading Culture through Code.” In Routledge Companion to Media Studies and Digital Humanities, edited by Jentery Sayers, 472–82. New York: Routledge. https://hcommons.org/deposits/item/hc:19537/.

McPherson, Tara. 2018. Feminist in a Software Lab: Difference + Design. Cambridge, Massachusetts ; London, England: Harvard University Press.

Mencia, Maria. 2017. “Introduction.” In #WomenTechLit, edited by Maria Mencia, viii–xxi. Morgantown, WV: Computing Literature.

Montfort, Nick, Patsy Baudoin, John Bell, Ian Bogost, Jeremy Douglass, Mark C. Marino, Michael Mateas, Casey Reas, Mark Sample, and Noah Vawter. 2013. 10 PRINT CHR$(205.5+RND(1)); : GOTO 10. The MIT Press.

Moretti, Franco. 2007. Graphs, Maps, Trees Abstract Models for a Literary History. ACLS Humanities E-Book. London ; Verso.

Nowviskie, Bethany. 2019. “Capacity Through Care.” Debates in the Digital Humanities 2019. Eds. Matthew F. Gold and Lauren K. Klein. https://dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu/read/untitled-f2acf72c-a469-49d8-be35-67f9ac1e3a60/section/3a53cbc1-5eee-421a-a4f6-82bb5dfb1c17

Pressman, Jessica. 2009. “The Aesthetic of Bookishness in Twenty-First Century Literature.” Michigan Quarterly Review XLVIII (4). http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.act2080.0048.402.

— 2014. Digital Modernism: Making it new in new media. Oxford University Press.

Pressman, Jessica, Mark C. Marino, and Jeremy Douglass. 2015. Reading Project: A Collaborative Analysis of William Poundstone’s Project for Tachistoscope {Bottomless Pit}. 1 edition. Iowa City: University Of Iowa Press.

Ramsay, Stephen. 2011. Reading Machines: Toward and Algorithmic Criticism. 1st edition. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Rettberg, Scott. 2013. “Introducing the ELMCIP Electronic Literature Knowledge Base.” Cibertextualidades, 257–61.

Salter, Anatasia, & John Murray. 2014. Flash: Building the Interactive Web. The MIT Press.

Tabbi, Joseph. n.d. “Manifesto.” CELL Project. Accessed June 4, 2019. http://cellproject.net/manifesto

Footnotes

Cite this article

Douglass, Jeremy, Mark C. Marino and Jessica Pressman. "Collaborative Reading Praxis" Electronic Book Review, 6 September 2020, https://doi.org/10.7273/b023-fx05