Digital Creativity as Critical Material Thinking: The Disruptive Potential of Electronic Literature

In this contribution to her co-edited collection, [Frame]works, Saum brings to the digital humanities both makers and theoreticians, gnosis as well as poiesis, school teachers as well as research professors.

This article has greatly benefited from the research group “Exocanónicos: márgenes y descentramiento en la literatura en español del siglo XXI” (PID2019-104957GA-I00), part of the Spanish Programa Estatal de Generación de Conocimiento y Fortalecimiento Científico y Tecnológico de I+D+i funded by the Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades.

Creative Making as Critical Thinking: A New Framework for the Digital Humanities

At the turn of the 21st century, literary critics like Johanna Drucker (2002), Jerome McGann (2001) or even digital poet Loss Pequeño Glazier (2002) wrote about the importance of “making things” as a way of doing theoretical work. The benefits of this have been widely discussed and affirmed since Drucker advanced that digital technologies could only be understood by praxis. In “Theory as Praxis: The poetics of Electronic Textuality,” she criticized the type of abstract approach embraced by postcolonial or structural studies at large, and explained that critiques of the foundations of textuality that were based on the terms of older philosophy were insufficient to deal with the new digital condition (Drucker 683). She turned to Jerome McGann’s Radiant Textuality to explain how poiesis, now conceptualized as theory, presented itself as the only valid means to capture the world’s new reality, after the digital revolution. Both McGann and Drucker understand poiesis in its literal Greek sense, as “building” or “construction” [i.e. “making”] in opposition to gnosis, as “conceptual undertaking.” “Making things as a way of doing theoretical work pushes the horizons of one’s understanding” (Drucker 684), she boldly asserted, and moved on to explain how this distinction between gnosis and poiesis was rarely considered in the Humanities, in part because participating in “hands-on” projects is not something humanists usually do.

Almost two decades later, this essay still responds to the necessity of finding another way of approaching Humanities’ projects that situates “making” at the heart of its doing, focusing in particular on the creative elements within its gnosis. While this “making-as-theory” paradigm could be applied to a variety of disciplines within the Humanities, I encourage its application to the Digital Humanities and, more concretely, to the pedagogy and scholarship on digital or electronic literature [e-lit]—i.e., born-digital prose or poetry. I find this to be the best locus to explore the division that Drucker and McGann pointed to, because these digital objects [whose existence is anchored in materiality] and the immateriality of the rational logos that sits behind the traditional, abstract and modern, humanities discourse are essentially in opposition. While new materialists such as Karen Barad, have astutely pointed out to the fallacy of thinking materiality under these dichotomic terms by reworking material ontology altogether under Barad’s “agential realist ontological” framework (Barad 2003) and others, the fact is that when it comes to thinking about materiality and disciplinary discourses this humanistic dichotomy remains stubbornly pervasive. New materialist positions like Barad’s could be considered a return to matter in the terms of Marxist historical materialism and its concerns about the embodied circumstance and the formation of the subject and discourse. However, emerging models of materiality in feminist theory such as hers do not reject the linguistic turn but are influenced by it in fostering “complex analyses of the interconnections between power, knowledge, subjectivity and language” (Alaimo and Heckman, 1) which have allowed feminists to understand gender as an articulation with/in other volatile makings such as class, race and sexuality. They do so, precisely, considering how spaces, conditions and material bodies contribute to the formation of subjectivity. Informed by this, this article first delineates a new conceptual framework for the study and practice of DH based on the concepts of new materiality and my own proposal of “critical creativity,” and it explores their implementation in three different e-lit projects covering the areas of pedagogy, curatorship and creative practice proper.

In How We Became Posthuman, N. Katherine Hayles explained that the modern discursive order is the product of a deeply ingrained belief in the duality of information that allowed it to exist separately from its material instantiation. This division, in its turn, had been productively implemented as a hierarchization of the two concepts within the rational discourse of Modernity, placing information first while relegating materiality to a second order of things. Further, reducing literature to a bodiless intellectual property, i.e., to mere “style and sentiment” in John Locke’s words (Rose 89), meant it could easily be regulated by copyright. Nonetheless, while this purported dualism has proven to be a lucrative presupposition in the context of print, when it comes to e-lit, this separation becomes paradoxically impossible because the information that builds it is inseparable from its digital materiality, as Kirschenbaum’s digital forensics have taught us (Kirschenbaum 13). Born-digital literature is always a performative expression that materializes during a process of machine translation between its output and its storage, which are always separated but become only significant when played together. A work of e-lit cannot be recited, printed or translated into another medium without a significant loss or change in its meaning; i.e., an e-poem is bound to its body in a way most traditional print poetry is not.1 Thus, e-lit is both a literary expression and a digital object bound to its material and performative body. E-lit’s essential duality challenges the modern order of things and discourse, while it requires a new conceptual paradigm for its understanding.

Interestingly enough, when it comes to the Digital Humanities [DH], a somewhat similar debate has been going on for the past decade. While there is an increasing number of publications engaging with the digital turn in literary practice, probably thanks to the normalization of the use of digital tools being applied to the study of literary texts within worldwide academia, authors like Alan Liu, Domenico Fiormonte, Tara McPherson, Isabel Galina, Élika Ortega or Katherine Fitzpatrick, among an increasing number of others, have expressed their concern about DH’s concentration on building and making digital tools to study cultural production without reflecting on the cultural aspects that building these tools entails in itself. In relation to literature in particular, it could be said that DH has mostly focused on reading digital texts as data but has failed to explore the literary value of those texts that were born digital in the first place.

Most of these critics point towards the dangers of participating in a “making” culture that addresses digital tools in an ahistorical and decontextualized manner. In their recent 2018 book, Digital Humanities: Knowledge and Critique in the Digital Age, David M. Berry and Anders Fagerjord have proposed a move towards a “Critical Digital Humanities” which is as critical of the digital as it is of the cultural, and where DH “continues to map and critique the use of the digital but is attentive to questions of power, domination, myth and exploitation” (139). In their view, critical DH offers a push back to the instrumental tendencies within DH, by explicitly contesting the neoliberal and market-oriented logics that are unthinkingly incorporated into DH projects, and the instrumentality also implicit in most digital design which “often tend to maximize instrumental values in their application of concepts of efficiency and organization and therefore are very difficult to resist” (141). Following their lead, Thea Pitman and Claire Taylor have proposed the term “critical DHML”, where ML [Modern Languages] stands for the necessity to keep alive the “common languages” that allow critical DH to keep a historical dialogue “with earlier (inter/trans)disciplinary frameworks such as ML” (Pitman, Taylor 2). In this way, the (inter/trans)disciplinary DH they imagine won’t lose “the ability to speak in the vernacular of the humanities” (2) as it embeds itself within an increasingly institutionalized global academia.

In order to combat the instrumental tendencies that lie hidden in our uncritical use of digital technologies and DH projects, Berry and Fagerjord suggest we make “connections to new forms of rationality that offer possibilities for augmenting or perhaps replacing instrumental rationalities,” (141) such as the “potentialities of critical computational rationalities, iterates and other computational competences whose performance and practice are not necessarily tied to instrumental notions of efficiency and order, nor capitalist forms of reification (Berry 2014)” (Berry, Fagerjord 141). Thus, Berry and Fagerjord do not propose to stop making, but encourage us to find other types of rationalities within digital making to enhance our conceptual undertakings in the Humanities. This may mean, “supplementing ‘the humanities’ own methodological toolkits’ with theoretical insights from software, critical code and platform studies” (Pitman, Taylor 4).

While I don’t disagree with the potential of this approach to DH, what I am suggesting inverts the traditional Humanities discursive order more radically, by situating making and materiality alongside or, even better, as conceptual undertaking, by taking the place of the immateriality of the rational logos. In order to avoid falling in the trap of instrumentalization, my e-lit framework does not “supplement” traditional humanities’ methodologies but inverts its rational order and asserts the importance of creativity over or, more accurately, within and as, critical thinking—not as computational thinking. As Patrick Finn defines it, critical thinking is a first-order linear model that deals with data in relational terms, unfit to deal with the dynamic, object-oriented and networked world of our contemporaneity (Finn 3). Creativity, in his view, opposes the structural limits of critical thinking, but I see it as something that can act complimentarily when taken critically. As Cornelious Castoriaris would put it, creativity can become a rebellious act of the “radical imagination,” becoming the sort of “critical creativity” that Christian De Cock, Alf Rehn and David Berry have proposed in “For a Critical Creativity: The Radical Imagination of Cornelius Castoriadis.” Under this framework, critical creativity departs from its neoliberal counterpart “innovation” seeing the imagination “in its essence rebellious against determinacy” (Castoriadis “Merleau” 2), liberating humans [and, now, literature] from any determinant logics of production or value creation. In Richard Florida’s infamous The Rise of the Creative Class (2002), for instance, creativity is presented as indivisible from profitability and marketability, leading the way to an empty rhetorical understanding of the term. As Shannon Jackson, Gregory Sholette, Sarah Brouillette or Lionel Pilkington have pointed out in one way or another, “when creativity is used rhetorically as a banner term it functions not just to disguise inequality, but also actively to promote it” (Pilkington), by using the expressive connotation of the word “creativity” to mobilize enthusiasm for the market economy. Creativity, in this sense is about “improvising, imagining and inventing, but strictly within the context of the absolute fixity of pre-determined economic assumptions” (Pilkington). Against it, critical creativity is all but rhetorical, looking at the material potentiality for change that escapes market assumptions by being both creative in Finn’s relational understanding as well as critical by allowing for the polemical energy that is the basis of criticism and critical thinking.

Fittingly, the concern between the relationship between creativity and these broader socio-economic logics has been at the heart of e-lit’s debates from the beginning. In “Creating a Third-Space for Electronic Literature,” Scott Rettberg suggested to imbed scholarship with creative practices as a means to occupy an already existing framework which he supposed to exist outside of the market. He explained his intentions behind the founding of the Electronic Literature Organization as an “institutional context where digital culture can be studied and produced, without being confined by the vocabulary of a particular established institutional context” (Rettberg 12). Following Rettberg’s reasoning, “creativity” and “innovation” would not be instrumental per se; in theory, their creative products would only become profitable when absorbed, regulated and commodified by capital. As valuable as the ELO is in exploring these matters, what remains to be explored is that even if e-lit is freed from an established institutional [regulating] context, this new space will not become fully liberating until we understand that creativity, and correspondingly, the human creator as well, still remain “locked into wider systems, including cultural worldviews and technological systems, that shape people’s sense of what is permissible, desirable and possible” (Szerszynski, Urry 3). In other words, as De Cock, Rehn and Berry put it, we become fully aware of the fact that “creativity is always-already social, and in our current historical moment this sociality is very much a neo-liberal one” (150).

In Castoriadis’s view, moreover, reducing and reifying something like creativity into something that supports existing social and economic structures ignores or marginalizes the ontology of imagination and replaces it with its institutionalized social imaginary (Castoriadis 1997, 108). In such an imaginary, “creativity can be domesticated as a handmaiden for capitalism and already known economic functions, and thus made into a pale shadow of its own revolutionary potential” (De Cock, Rehn, Berry 156). Unfortunately, creating a third-space for e-lit or even DH projects does not automatically break this paradigm but, as I will explain in the following sections, framing e-lit as a practice and product of critical creativity may. In its turn, this e-lit framework reinforces the importance of applying radically non-traditional [philosophical, literary, artistic] methodologies to Digital Humanities programs over all.

Centered around creativity, this non-traditional or post-Humanities paradigm acts, as well, as the type of “posthuman thinking” embedded in Rosi Braidotti’s (2013) take on new materialism, which she has proposed in order to overcome the current stagnation of the traditional Humanities paradigm. Braidotti understands this paradigm to be based on universalist, unjust, and abstract rules not suited for the current digital era. In response, she pursues alternative schemes of thought, knowledge and self-representation emerging from an embodied and embedded and “partial form of accountability, based on a strong sense of collectivity, relationality and hence community building” (49). In an attempt to defend the relevance of DH projects thus, I’ll explore three examples of how I have implemented a material, critical creativity paradigm to the study of e-lit: a creative teaching experiment and two modes of what I have termed “material discourses” as posthumanistic alternatives to rational and immaterial humanistic scholarship.

Teaching Electronic Literature as [Creative] Digital Humanities

As I discussed in “Teaching electronic literature as digital humanities,” teaching e-lit by emphasizing “making as theory” allows us to address three fundamental pillars in the humanities. Firstly, the overall concept of literature, and more specifically, the literary; secondly, what we understand by literary studies at the university; and thirdly, and more broadly, what constitutes cultural [beyond technical] literacy in the twenty-first century (Saum-Pascual “Teaching”). In that article, I began by explaining that in our current context, “cultural literacy” or “literacies” could be reduced to simply mean “digital literacies,” as a shorthand for “the myriad social practices and conceptions of engaging in meaning making mediated by texts that are produced, received, distributed, exchanged, etc., via digital codification” (Lankshear, Knobel 2008). These can be as varied as the behavior of different Twitter users, writing an academic paper online, or emailing a relative. I also made an argument for the importance of incorporating these practices to the study of literature in the university, believing in the value of teaching digital art forms that include a literary dimension to promote literacy and vice versa (Saum-Pascual “Teaching”). I concluded that essay writing about the importance of treating the digital literary under a media specific framework for the benefit of our broader humanistic inquiries around literature. And what I meant by all this was essentially that teaching e-lit as DH—and as a foreign language–effectively addressed all three. I elaborate on some of these concepts briefly here, but this time I add “creativity” to the list of fundamental pillars of the Humanities, now understanding creativity as an integral competence to critical thinking, as mentioned earlier.

I am primarily a Spanish literature scholar, so naturally when I first thought about this I was coming from the perspective of the foreign or modern languages. After all, “we are facing a type of literature that necessarily combines different semiotic languages (sound, movement, text), but also programming and formal languages (JavaScript, Perl, Phyton, etc.) and natural languages that can be expressed in different tongues (Spanish, Portuguese, English, etc.), that can or cannot be framed by any single one of these languages’ literary traditions” (Saum-Pascual “Teaching”). Jessica Pressman has famously proposed to frame this mix as “comparative literature”—noticing that e-lit operates across multiple machine and human languages, and requires translation of these languages before it even reaches the human reader (Pressman)—but I thought it was more productive to think of this combination as a foreign language in itself, “the ultimate global language” (Saum-Pascual “Teaching”). Whichever the case, as comparative or foreign literature, e-lit was being conceived more like a language than a literature; more exactly, like a “competence”: the literary competence; rather than a subject or an object, making the difference between teaching a skill or a knowledge less important than the capacity to learn how to apply a set of related knowledges and skills in order to perform a given task, usually in a community setting.

Teaching e-lit as literary competence, seen now as part of a larger “digital humanities literacy,” allowed me to also claim that e-lit belonged in Modern Language Departments [moving DH away from English or History departments where it is mostly taught in U.S. academia], pointing towards the need of an administrative change, but also a deeper epistemological and methodological one. Teaching competencies under this framework would “categorize ‘to learn’ as an intransitive verb, rather than teaching to learn about something concrete” (Saum-Pascual “Teaching”) which correspondingly would conceptualize “to teach,” and more broadly, consider “reading literature” as “’building,’ ‘designing,’ ‘touching’ and/or ‘listening,’ for instance, rather than reading literature as something that depends on our eyes and minds solely” (Saum-Pascual “Teaching”). What I didn’t know then was that creativity would be the common denominator to all this.

When teaching “Electronic Literature: A Critical Making & Writing Course” in the Spring of 2016, for instance, I saw immediately how creativity rose to the forefront of teaching literature as this type of competence. This was a course I taught at the University of California, Berkeley, cross-listed between the Spanish and Portuguese Department and the Berkeley Center for New Media, also listed as part of the Digital Humanities program at Berkeley. It was an upper division, undergraduate writing intensive class, where students learned how to write and talk about e-lit learning specific terminology and theoretical frameworks, as they gained the skills to build their own digital art pieces in a collaborative workshop setting. It incorporated academic research tools and resources, together with practical, hands-on work, that allowed us to develop new theories of the digital literary, as well as explore how e-lit could help us reevaluate computational practices. Following Johanna Drucker and Lauren Klein’s characterization of DH as an inquiry into “how we know what we know,” in this type of course, students “connect[ed] questions of epistemology to questions of method and form by shaping their own ‘interpretive task,’ probing their own research questions, and pursuing scholarship in digital or analog forms” (Klein 42).

“Electronic Literature: A Critical Making and Writing Course,” was divided in two correlating modules: critical writing and critical making; designed to explore these issues and methods hands-on; i.e: teaching gnosis through poiesis. The first module dealt mainly with improving students’ [foreign language] writing skills and critical analysis of aspects particular to electronic literature, while the second was meant to encourage enactment of those conceptual topics. For instance, by exploring original e-lit works, students debated questions of originality [unoriginal genius, remix, appropriation, etc.] while also learning how to tweak the code of textual generators; they explored textual ontology [code ontology vs. print ontology] while building Augmented Reality experiences with mobile apps; or they challenged narrative structures [hypertext vs. linear narrative] while building simple Twine programs, among many other topics and tools.

Students were also asked to reflect on their own readings and making by writing short critical commentaries on how these techniques could be used further, for their own creative enterprises. For instance, after reading through Belén Gache’s e-poetry collection Wordtoys together with Ulises Carrión’s The New Art of Making Books, students were asked to explore the affordances of the book as a print platform, while reflecting on wordtoys’ own digital affordances. They would then explore a variety of tools to produce decentralized and disembodied reading experiences in order to enact their own conceptual undertakings. Students were not necessarily required to build a program or a tool from scratch but rather encouraged to redeploy existing ones in order to make their own creative pieces of e-lit [The complete list of projects and plans can be accessed by the bilingual course site: http://eliterature.digitalhumanities.berkeley.edu]. In this sense, I followed Laura Klein and Bethany Nowviskie’s view on “hacking” as a “metaphor for approaching knowledge—a method of reconfiguring a system, or redeploying a tool, in a way that is different from its original intent” (Klein 42). As Klein admits, “hacks” “are often imperfect, but they are also often quickly implemented, with the aim of solving a specific problem or enhancing overall function or use. The success of a hack is judged in equal parts by its effectiveness and the creativity of its method” (42).

Creativity is hence central to this paradigm, since “creativity” is all about “making” new things. It is a way of reaching new knowledge, and I believe creativity can and should be taught and exercised in DH; in this particular case, as e-lit and as “hacking.” In this course, for instance, although “making” was at the core of the experiment, the building of the tool was not its focus. Poiesis was found in taking apart and redeploying existing technologies which are inseparably intertwined with our digital experience; creativity thus became the most suitable framework to understand the “networked world of our contemporaneity,” as Finn would put it. Creativity and making took over traditional critical thinking, but this creativity was indeed “critical.”

Cornelious Castoriadis has explained how western philosophy has established itself as the elaboration of reason, leaving creativity aside [for critical thinking] and by doing so, covering over the “positive rupture of already given determinations, of creation not simply as undetermined but as determining, or as the positing of new determinations” (“Merleau” 1). He believes the imagination essentially rebels against determinacy and understands the historical to be inseparable from the social: i.e., History does not exist as a determinate chain of events, its powered by us, humans. We “can provide new responses to the ‘same’ situations or create new situations” (Castoriadis, Imaginary Institution 44) making our lives “not the determined sequence of the determined but the emergence of radical otherness, immanent creation, non-trivial novelty” (184). As Christian De Cock, Alf Rehn and David Berry have explained as well, for Castoriadis “creation” truly means “creation ex nihilo” (De Cock, Rehn, Berry 151), this is, the bringing into existence of a form that was not there, “the creation of new forms of being … of forms of language, the institution, music, painting…” and, let me add, literature. It is precisely our capacity for creation that shows us why the essence of the Human cannot be its rationality as operant logic. In other words, they conclude “the productive function of creativity is for Castoriadis an open issue, and not guaranteed to fit neatly into any given societal or economic arrangement. In extension, this also points to an understanding of Man (sic) as free from any determinant logics of production or value creation” (De Cock, Rehn, Berry 151). Creativity is productive while remaining un-instrumental.

As productive as this critical paradigm is to teaching in general, and to DH in particular, the radical value of creativity goes beyond pedagogy. Embracing critical creativity will turn us into better teachers and will help our students tremendously but will also make us better researchers and better artists—because this larger framework that I am proposing can’t separate our artistic [creative] practice from our scholarly or pedagogical [also creative] work. Earlier I expressed the need to invest in finding new ways of doing scholarship that considered creativity and materiality as essential aspects to the study of digital matters. This may mean supplementing the humanities’ own “methodological toolkits” with theoretical insights from software, critical code and platform studies, as Taylor and Pittman have suggested. Or it may imply an even more radical change to “writing” and “reading” that moves beyond “supplementing” to changing the form of scholarship altogether. I understand this as finding forms of scholarship that resemble more closely the object of study, the literary digital object in this case, in order to learn from its inherent logic and material ontology. In what follows I present an example of an exhibition of electronic literature and a creative writing project as two instances of what I am calling “material discourses,” in order to do just this. Nonetheless, the fundamental takeaway in this critical creativity proposal is not its digital object nor even the two forms I present, but the overarching methodology that emerges from their digital condition: a paradigm shift that, as I mentioned earlier, transcends the traditional one operating in present day Humanities for one we may as well call post-humanities or, why not, materially posthuman.

Creativity and Scholarship by Other Means, Take I: the Exhibition as Material Discourse

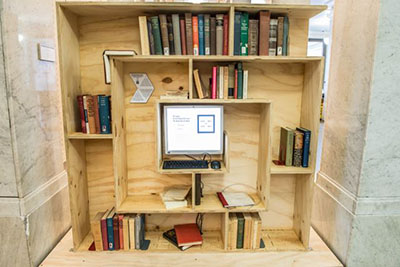

Back in 2016, together with my colleague Élika Ortega and several collaborators at UC Berkeley from the Library and the Berkeley Center for New Media, I co-curated an electronic literature exhibit on display first at Doe Library in Berkeley [March-Sept 2016], then at the California College of the Arts in San Francisco [Feb-May 2017]. No Legacy || Literatura Electrónica [https://nolegacy.berkeley.edu] showcased a collection of digital objects displayed in historical media as well as in tablets and contemporary machines, together with a selection of print matter from the Hispanic and Lusophone Avant-Gardes.2 All digital objects were thus performed by machines that were historically accurate, maintaining their original tempo, rhythms, sounds and colors display. New and old together, each object’s temporality, ergonomics and tactile qualities were maintained, bringing back that empirical experience of its past to the present where it was now being activated, emphasizing the temporal breach between both experiences and their reencounter and coexistence at the exhibition, where visitors could experience them.

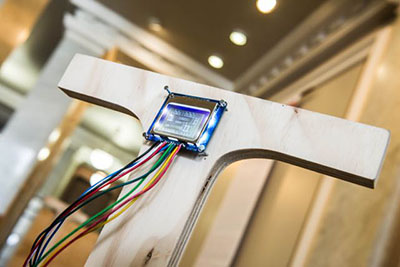

Moreover, in order to explore how poetry could be enacted even further by this type of material experiencing of the literary object, we translated certain digital motifs central to our e-lit pieces into other types of physical installations within the gallery. Instead of placing the computers on a desk with its corresponding chair, we built wooden labyrinths to travers with the touch of the hand; instead of shelves to display an iPad we imagined round bookcases with spinning shelves; instead of imitating the iconicity of experimental typography on a printed page, we carved wooden letters as tall as a person, etc.

Next to these computers and installations we displayed over 50 works of experimental print matter ranging from Mexican stridentism, Spanish futurism and Brazilian concretism to Magical Realism or the work of Borges and Cortázar, now also meant to interrogate the particular rhythms and ruptures of the digital. For instance, Carlos Oquendo de Amat’s accordion poem Cinco metros de poemas was placed next to J.R. Carpenter’s web-based Etheric Ocean, both proposing a media specific type of horizontal reading, while the hypertextual and generative structure of its name was Penelope by Judy Malloy interrogated the magical temporality of Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, and so on. In this way, 18 e-lit pieces and 50 print works questioned each other in terms of tension, analogy or coincidence for the duration of the show.

With this exhibit we implemented a material and archeological, rather than abstract and historical, perspective to the study of literature, creating a space of action, i.e. the gallery, that allowed us to physically connect that which in theory was separated. As Siegfried Zielinski would put it, we aimed to abandon conceptual schemas and images that reproduced an illusion of progress in lineal or hierarchical terms in favor of the individual variations in the use of media that defy “the uniformity among the competing electronic and digital technologies” (10), that which he calls “variantology.” Observing individual variations, those that had been left at the margins of the History of technological progress, we were able to experiment the emergence of other possible futures. By connecting literary works in the basis of their materiality we undid and challenged the overarching theories of evolution and influence that had ruled the works’ literary histories until that point. Thus, by treating literature as an object, we were able to put at the background traditional classifications in the study of literature [classifications like language or its geographical origin, for instance], while bringing to the fore other aspects such as its conceptualization and enactment of time. Further, treating literature as an object in a gallery allowed us to trace discontinuous and rhizomatic connections with other objects that defied our preconceptions of the literary. Each connection belonged to a unique empirical experiencing of the gallery, each visitor creating new connections, producing new type of knowledges—writing a new type of material essay, let’s say, and thus participating in a new methodological proposal to the study of literature.

In The Posthuman, Rosi Braidotti understands that the main criteria for posthuman theory is not its object but the methodology that is applied to an object. She believes that the heteroglossia of data we face nowadays demands “complex topologies of knowledge for a subject structured by multi-directional relationality. We consequently need to adopt non-linearity to develop cartographies of power that account for the paradoxes of the posthuman era” (Braidotti 165). These cartographies she refers to are ways of reading aimed at the epistemic and ethical accountability that shape the structure of our positioning in the world; they account for “one’s locations in terms of both space (geo-political or ecological dimension) and time (historical and genealogical dimension)” (164), as they emphasize the situated structure of critical theory which implies its partiality and “the limited nature of all claims to knowledge” (164). Evidently, this framework is crucial to the type of critique to the universalism and abstraction of the modern rational discourse that I am considering here, as well as to the interconnectivity between different elements in a collection that the exhibition itself entails.

On the other hand, Braidotti defends the practice of “creative figurations” as an alternative means of representation. This is a process that conceives subject formation as taking place in between “nature/technology; male/female; black/white; local/global; present/past—in the spaces that flow and connect the binaries. These in-between states defy the established modes of theoretical representation because they are zigzagging, not linear and process-oriented, not concept-driven” (164). Creativity is key in this posthuman search for thought alternatives that is founded in a non-linear view of History and memory now conceptualized as imagination (165). This dynamic conception of time also “enlists the creative resources of the imagination to the task of reconnecting to the past” (165), resembling Zielinski’s media theory. A web-based work like the mentioned Etheric Ocean by J.R Carpenter that proposes horizontal scrolling as its reading directionality sheds light not only on how easily we have adopted verticality to be the most natural way to read screens that could potentially grow in any direction, but also to rethink the limits of the book and the temporal sequence proposed by its pages as it relates to writing and reading poetry when it is placed alongside a 20th century accordion poem. It is not that artist books of poetry have influenced digital writing, is that digital experimentation can allow us to see book constraints in a novel way. Book history and its evolution can be traced now from several new points of origin, creating new figurations such as those proposed by Braidotti.

This posthuman methodological proposal is of paramount importance to the change in the Humanities’ discourse that I am interested in. Non-linearity affects scholarly practice by allowing for “multiple connections and lines of interaction that necessarily connect the text to its many ‘outsides’” (Braidotti 165). This method affirms that “the ‘truth’ of the text is never really ‘written’ anywhere, let alone within the signifying space of the book. Nor is it about the authority of the proper noun, a signature, a tradition, a canon, or the prestige of an academic discipline” (Braidotti 165). The truth that Braidotti seeks requires an altogether different form of responsibility and respect [or “accountability” and “accuracy” (165)] that is found in the “transversal nature of the affects they engender” (165), in other words, in the interconnections that are allowed and maintained with the outside world. Braidotti’s posthuman methodology captures the radical potentiality of Castoriadi’s imagination but, unfortunately, capturing the dynamic connections it establishes with the creative outside is only possible by allusion by my writing in this text.

The material discourse of the exhibition, however, where the body of the machine and the visitor who reads with her own body is positioned against the logos, in its abstract, historical and singular dimension, is successful in building new relationships of emergent knowledge and affect between them and the other bodies visiting the exhibition simultaneously and at different times. On the one hand, this type of transversality “actualizes an ethics based on the primacy of the relation, of interdependence, which values non-human or a-personal Life” (Braidotti 95). This is what Braidotti calls posthuman politics. On the other, it situates creativity at the core of this transversal emergence born out of “making” and “materiality.” Thinking of the exhibition of e-lit as a possible type of posthuman discursive practice seems fitting within this framework, but it doesn’t have to be the only way.

Creativity and Scholarship by Other Means, Take II: Making E-Poetry as Material Discourse

More or less around the same time I was working on No Legacy and teaching “Electronic Literature: A Critical Making and Writing Course,” I began to make my own creative e-lit pieces as another alternative to the Humanities discourse I considered to be insufficient to study e-lit, and by extension, DH. The key to these poems was their material dependency on the digital medium I chose to build them on, making their consumption or translation through any other means impossible. I wanted to emphasize the multidimensional, layered, and interconnected structure of the digital object as it exists today in digital culture, as I explored its precariousness aesthetically to show the many ways in which everything in our lives is not only hanging from unstable digital infrastructures but is also always contextual and partial, material and, more importantly, interconnected, as new materialists (Alaimo, Heckman, Barad, etc.) and most posthuman theory (Braidotti, Hayles, Haraway, etc.) have posed. My positioning within the poems themselves was crucial too, as the subject needed to reflect the same type of transversality, accountability and accuracy as the methodology I was implementing. I thought of nothing better than working with my own body and image, and thus I created #selfiepoetry [Vols. 1 and 2], as a series of multimedia and interactive poems built through patching together elements distributed through different social media sites that would also only fully exist on external sites, never keeping a local copy. This, in a way also mimics the distributed nature of almost any website.

This meant that most of my early #selfiepoetry work was also only accessible via a computer connected to the internet, requiring in addition specific hardware elements like audio output, a keyboard and a mouse, or trackpad. These precariously patched together, yet materially demanding, poems were not to be displayed on mobile devices like smartphones or tablets, forcing the reader to be in a particular position and a [most likely] domestic space, that would always already be part of a connected network. The performativity of the poems fully depended on band speed as well as on the “correct” functioning of the commercial servers where the poems were stored. These poems were heavy and took unreliable and unpredictable time to load, some elements even went missing depending on where they were being stored and from where they were being retrieved, and some functionality was also deactivated at times. This made each viewing unique and unpredictable as I relinquished my digital creations to the unreliable and nefarious online infrastructures to which we so happily hand over many aspects of our lives.

The result was a type of digital work whose poetics were absolutely dependent on the external infrastructure where there exist and absolutely independent from me as author—and, because these were “selfies,” me as subject too. Once built, I gave up all control over the matter, to the extent that once a site is down, my oeuvre becomes inaccessible to even me—the materiality and interconnectivity of literature comes painfully to the forefront, to the point that most of my work is now lost and only saved by video documentation.3 Ephemerality and unpredictability are inextricable from the poetics of our digital experience online.

My first #selfiepoetry collection was called Fake Art Histories and the Inscription of the Digital Self [http://www.alexsaum.com/selfiepoetry-vol1_fakearthistories/] and as I described it then, this was a series of eight bilingual poems [Spanish/English] meant to explore the intertwining of two main ideas: “the (un)truth behind artistic or literary histories and our (il)legitimacy to intervene and organize events to create narratives that ‘make sense,’ vs. the interpretative role of the recipient of said narratives” (Saum-Pascual “#selfiepoetry”). I was also intrigued by the roles assigned to the producer of art and its consumers, “roles that have been traditionally separate and that have begun to blend and blur indistinguishably thanks to their performance on digital media” (Saum-Pascual “#selfiepoetry”), perhaps giving birth to that figure that Henry Jenkins originally called “the prosumer,” but which today seems to have been reduced to an exercise in constant individual reaffirmation turning the subject into an object of amateur representation and massive distribution via social networks [i.e. posting selfies]. The subject and its paradigmatic photographic representation is poorly multiplied and reproduced through different digital platforms inscribing itself in the multiple temporal and spatial dimensions of the web. Let’s put it slightly differently, we are obsessed with the traveling of our faces—and this runs deeper than taking a bathroom selfie at the club.

Fake Art Histories plays with some of those inscription mechanisms, placing the self against a very vague and unorthodox selection of artistic and literary trends. There are poems about futurism and polyamory, about plagiarism and Borges’s dreamtigers, about immigration to the United States and Walt Whitman’s sexual orientation, about the measure of the renaissance man and women on YouTube, among others. One of my earlier poems, “The Measure of All Things” deals precisely with this last topic, juxtaposing the Renaissance’s belief on the human body as cosmografia del minor mondo [a sort of analogy of the world] against the multiplicity of representations of the subject in the macro-world that is the web.

The poem, the size of one single screen, is built over Leonardo Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man. The man of “ideal anatomic proportions” serves as background to a written sentence “Your Digital Presence Is the Measure of All Things” and nine YouTube videos of different transparencies play automatically 4 different versions of myself, showing only the face this time, reading Garcilaso de la Vega’s sonnet XXIII. This is a canonical Golden Age poem by the famous poet-soldier who brought the Italian Renaissance to Spain in the 16th century, now being remediated to the YouTube format and aesthetics, characteristic for their “amateur footage, edited on a desktop, intended almost as throwaway pieces of culture” (Hight 5). Courtly love’s carpe diem is trapped in an endless loop of cheap looking videos that have abandoned all hopes of transcendence or originality. Nine copies of my face now repeat the poem with different intonation, interrupting each other and turning poetic speech into unintelligible white noise.

The self is lost in the automatic form of a robotic representation, now also taken by a megacorporation such as Google, owner of YouTube, alienating it completely from the subject. The reader can let the poem run its course [it has no end, once started it will run for as long as its larger material infrastructure let it—from the electricity powering the computer that receives it to the server that stores it] or can choose to play with the poem stopping and starting each of the nine videos at will. This way, I let my reader interact and “play” with my image as its body unfolds and inscribes itself in other media, as another non-biological experience that is, in its turn, handled by another bios; i.e., by the human body of the reader.

What these poems underscore is not a question of leaving the technological or the human body behind, but the importance of a specific, local and material experience that would not be possible without the participation of digital technologies. Presenting the human subject as partaking in digital making consciously inscribes her actions in a distributed system that, in its turn, allows us to experiment with/ to enact/ to make our critical potential as part of that network and its collectivity. When thinking about bodies, matter and performativity from a posthuman perspective such as this, we are forced to also rethink our notions of discursive practices and material phenomena, and the relationships among them. Karen Barad describes her “agential realist account” as one where discursive practices are “not human-based activities but rather specific material (re)configurings of the world through which local determinations of boundaries, properties, and meanings are differentially enacted” (Barad 828). Informed by quantum physics, in Barad’s material philosophy matter is not a fixed essence, “rather, matter is substance in its intra-active becoming—not a thing but a doing, a congealing of agency. And performativity is not understood as iterative citationality (Butler) but rather iterative intra-activity” (828). What this idea of performativity means for poetics and the making of digital objects is that the maker, the poet, and the “enacter” [i.e. user, reader, knower] are never in a relation of absolute externality to the world [poem, object, etc.] being investigated. The condition of possibility for objectivity is thus not absolute exteriority but rather agential separability: “exteriority within phenomena” (Barad 828). It is, as she explains, not a simple question of subjective knowledge, but a reconfiguration of objectivity understanding that “’[w]e’ are not outside observers of the world. Nor are we simply located at particular places in the world; rather, we are part of the world in its ongoing intra-activity” (Barad 828, emphasis in the original). In other words, the posthuman material performativity that Barad describes and that is at the heart of my precarious and network-distributed #selfiepoetry positions the subject, the work and the object as constituting and part of a multiplicity that although internally differentiated is also deeply grounded and accountable.

Conclusion: The Imagination of Better Futures

In conclusion, be it in the form of an exhibition, or by making art, or by implementing these material discourses into our creative pedagogies, this methodological framework allows for the emergence of a different voice to talk about digital technologies, about digital objects, about the Digital Humanities. A turn in discourse is a turn in method that now considers its voice to be necessarily situated but distributed, unique but multifaceted, concrete [as it is matter] and subjective as a possibility for relational objectivity. Consequently, such a move involves taking creativity seriously and putting it at the center of our thinking and relationship with the world. Critical creativity is not considered a utilitarian addition, “something to call upon when vertical/rational thought reaches an impasse, as if ‘creativity’ were simply a special weapon in the armory of the ever-so-rational homo oeconomicus” (De Cock, Rehn, Berry 159). As the themes of creativity, innovation and the imagination are being coopted by the creative industries of neoliberalism, a turn to Castoriadis and posthuman and feminist materiality provides a framework to liberate these concepts and brings a new political dimension to the jaded discourse of the Humanities. Engaging in the practices I’ve outlined here, in turn, also points our gaze to the future, abandoning the liberal and abstract discourse of modernity to become materially engrained in the present while, yes, making us to look ahead and forward. Once the traditional Humanities discourse is left behind, DH and e-lit become a sort of prophetic prescription for the future based on critical creativity. The rebellious nature of creativity, in opposition to determinacy, is based on its quality of being always “not effect of, but condition of desire, as Aristotle already knew: ‘There is no desiring without imagination” (De Anima 433b29 qt in Castoriadis “Merleau” 2). In other words, the future becomes the active object of desire it always was, because it “propels us forth and motivates us to be active in the here and now of a continuous present that calls for both resistance and the counter-actualization of alternatives. The yearning for sustainable futures can construct a livable present” (Braidotti 192). Under the framework I am proposing for the study of e-lit and DH, but more broadly, for all of the Humanities taking these two disciplines as beacons, critical creativity becomes something wildly transformative that disrupts and changes the way we say, make, and do things. Creativity becomes a ballast to rationality, and in effect “provides a counterweight to the actuality of the world” (159). Obviously, this applies to teaching, researching and all other creative things we do in academia, but it assumes a more radical and more valuable reconceptualization of the University in the 21st century, and, more importantly, the world we live in.

WORKS CITED

Alaimo, Stacey and Susan Hekman Eds. Material Feminisms. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 2008

Barad, Karen. “Posthuman Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter” Sings: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 28.3 (2003): 801-831.

Berry, David and Anders Fagerjord. Digital Humanities: Knowledge and Critique in a Digital Age. London: Polity Press, 2017

Braidotti, Rosi. The Posthuman. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2013

Castoriadis, Castoriadis. The Imaginary Institution of Society. Cambridge: Polity, 1987

____ “Merleau-Ponty and the Weight of the Ontological Tradition.” Thesis Eleven, 36.1 (1993): 1-36.

____ “Anthropology, Philosophy, Politics.” Thesis Eleven, 49.1 (1997): 99-116.

De Cock, Christian, Alf Rehn and David Berry. “For a Critical Creativity: The Radical Imagination of Cornelius Castoriadis.” The Handbook of Research on Creativity. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2013. 150-161

Drucker, Johanna. “Theory as Praxis: The Poetics of Electronic Textuality,” Modernism/Modernity, 9.4 (2002): 683-691.

Klein, Laura. “Hacking the Field: Teaching Digital Humanities with Off-the-Shelf Tools.” Transformations: The Journal of Inclusive Scholarship and Pedagogy. 22. 1 (Spring 2011/Summer 2011): 37-52.

Kirschenbaum, Matthew. Mechanisms: New Media and the Forensic Imagination. Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2008

Lankshear, Collin and Michelle Knobel. “Introduction.” Lankshear, C., and Knobel, M. (eds), Digital Literacies: Concepts, Policies and Practices. New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 2008. 1-16.

Hight, Craig. “The field of digital documentary: A challenge to documentary theorists.” Studies in Documentary Film 2:1 (2008): 3-8.

McGann, Jerome. Radiant Textuality. Literature after the World Wide Web. New York: Palgrave, 2001

Nowviskie, Bethany. “Digital Humanities Down Under (State of Play; Why You Care).” Nowviskie.org. 14 December 2010. Web. 19 Jun 2019. http://nowviskie.org/2010/digital-humanities-down-under-state-of-play-why-you-care/

Pequeño Glazier, Loss. Digital Poetics: The Making of E-Poetries. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2002

Pilkington, Lionel. “The Contested Meanings of Creativity”. The Moore Institute´s Blog. Web. 23 May 2017. https://mooreinstitute.ie/2017/05/23/contested-meanings-creativity/

Pitman, Thea, and Claire Taylor. “Where’s the ML in DH? And Where’s the DH in ML? The Relationship between Modern Languages and Digital Humanities, and an Argument for a Critical DHML.” Digital Humanities Quarterly 11.1 (2017): 1-16.

Rose, Mark. Authors and Owners: The Invention of Copyright. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1993.

Saum-Pascual, Alex. Teaching Electronic Literature as Digital Humanities: A Proposal.” Digital Humanities Quarterly 11.3 (2017): 1-14.

____ “#selfiepoetry Vol1*FakeArtHistories.” alexsaum.com. Web. 19 Jun 2019 http://www.alexsaum.com/selfiepoetry-vol1*fakearthistories/

Szerszynski, Bronislaw and John Urry. “Changing Climates: Introduction.” Theory, Culture & Society 27.2-3 (2010): 1-8.

Zielinski, Siegfried. Deep Time of the Media. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2008

Footnotes

-

A similar observation may be made in the case of visual or concrete poetry, and to a certain extent, to sound or spoken poetry. It could also be argued that a translation of poetry into any other natural language cannot be done without losing substantial culturally determined knowledge that is imbedded in the linguistic term. The main difference here, however, is the attention I pay to the digital body of e-poetry, whose layered materiality is ontologically different to any other media, as I argue throughout the essay. ↩

-

Main team was composed by Alex Saum-Pascual, Curator and Project Coordinator; Élika Ortega, Curator; Claude Potts, Curator for Print; Stephanie Lie, Lead Exhibition Designer; Aisha Hamilton, Library Exhibition Design Liaison; Cody Hennesy, Coordinator for Digital; Cristina Sá, Consultant for Portuguese; David Wong, Lead for Computer Infrastructure Support; Sam Hunnicutt, Student Docent ↩

-

These early poems were hosted by newhive.com, which was hacked in mid 2019. The site is now defunct, and all its content lost. ↩

Cite this article

Saum-Pascual, Alex. "Digital Creativity as Critical Material Thinking: The Disruptive Potential of Electronic Literature" Electronic Book Review, 2 August 2020, https://doi.org/10.7273/grd1-e122