Ethics and Aesthetics of (Digital) Space: Institutions, Borders, and Transnational Frameworks of Digital Creative Practice in Ireland

Discussing the works of three digital creative practitioners working in Ireland, Anne Karhio situates Ireland itself as a case study for demonstrating the ways in which electronic literature as a seemingly global and transnational practice can confront the complexly situated realities of everyday embodiment, technological materiality, and politicization of national borders. She thus recommends electronic literature be seen as more crucial part of digital arts and humanities research in Ireland and elsewhere.

This essay considers Ireland, and works by creative practitioners based in Ireland, as a case study for examining relations between local, embodied contexts, and transnational aesthetics and exchanges in electronic literature and art.1 In doing this, it also recognizes how creative practice in the digital domain can be considered a framework for digital humanities, and for critically scrutinizing the national and transnational dimensions of institutional practices in digital humanities research. Such research highlights the entanglements between digital research methods and the communications networks, infrastructures, and economies that sustain them. The focus on the transnational allows for a recognition of the continuing impact of geographical and political borders on literature and the arts in the digital domain, but also how practitioners address questions related to these borders and boundaries through their chosen medium. While the web has been seen to free authors, artists, and communities from the constraints of physical location, it is nevertheless shaped by national and regional boundaries that are continually and persistently enforced, problematized, and in need of revision. Perhaps more than any other phenomenon, the global pandemic of the COVID-19 virus during spring 2020 has forced many to recognize how regional borders within individual nation states, even the borders within the Schengen area that should guarantee free movement of people between many member states of the European Union, can be quickly reinstated when communities are deemed to be under threat from outside contagion. This raises the question of how such borders are determined, who they protect or leave without protection, and who might still be allowed free access, and highlights the tenuous character of the unobstructed mobility between countries and regions that the citizens of the Global North have presumed to enjoy in the 21st century context.

As an island, Ireland’s geographical boundaries may appear deceptively clearly defined. Yet the border between the Republic and the six counties of Northern Ireland, nearly invisible in the landscape, is a continuing reminder of the complexities related to the island’s colonial legacy. The Irish border prompts questions related to the unobstructed movement of ideas, goods, services, and capital as the Republic has become a hub of multinational IT corporation headquarters in Europe, attracting investment in network infrastructure (data centers, cable networks, and landing stations). Historically, the present-day situation was anticipated by the construction of 19th century transatlantic telegraph infrastructure with landing stations on Ireland’s western seaboard, and the subsequent construction of numerous wireless telegraph stations along this same coast.2 Transnational systems of exchange through transport and communication thus precede the emergence of the independent nation as a cultural/geographical entity, and continue to inform the way in which everyday material encounters as well as creative practices are negotiated within political, economic, educational institutional frameworks. Creative practitioners in born digital literature and art are, however, uniquely equipped to respond to these frameworks as local manifestations of global information networks and platforms.

Digital creative practice and creative communities fostering it occur across geographical borders, which can also become the intermediary zones through which social and technological relations are explored. This is particularly the case in Ireland, which has become a microcosm of the various tensions related to global network economies and infrastructures. It is a small, European nation state with a long history of emigration and complicated colonial encounters, now a hub of multinational tech corporations attracted by the country’s low tax rates, and a political establishment with a mixed track record in tackling increasing social inequalities, and various humanitarian crises within and outside its borders. It is a space where the ethics and aesthetics of digital media interfaces and infrastructures co-exist with the politics and economy of network capitalism, and the flow of transnational capital, goods, and people. Ireland has a cultural self-perception characterized by a strong sense of local rootedness, but also an equally strong tradition of constant mobility and transit. As the often-quoted author and journalist Fintan O’Toole has phrased it in the context of the Irish diaspora, “Ireland is often something that happens elsewhere” (O’Toole 12). Increasingly, in the age of digital media, this “elsewhere” also happens in Ireland, or the distinction between “here” and “elsewhere” is becoming more and more difficult to define, despite the newly highlighted geopolitical relevance of national borders in a world tackling the recent pandemic. In short, transnational ethics and aesthetics are constantly renegotiated amid tensions between mobility, migration, and national on the one hand, and, on the other, forms of national and cultural belonging.

The following discussion examines the tensions between institutional boundaries, geographical and political borders, and transnational exchanges in the works by three digital creative practitioners working in Ireland: El Putnam’s Quickening (2018), Elaine Hoey’s The Weight of Water (2016) and Animated Positions (2017), and Conor McGarrigle’s #RiseandGrind (2018). The works explore different aspects of how digital technologies and media platforms frame our situated, everyday experiences at a local level – through performance and video, immersive VR and game aesthetics, and generative network installations. At the same time, they recognize how transnational digital networks and platforms perpetuate sociocultural divides, and can be adopted for a critique of such inequalities through ethically or politically informed spatial aesthetics. All of the discussed projects highlight how, as Dale Hudson and Patricia R. Zimmermann have argued, “[n]ew media ecologies produce transnational environments, where physical and bodily location simultaneously matters and does not matter” and “[l]ocative places often emerge where the laws of transnational environments are interpreted” (Hudson and Zimmermann 10, 12). As they reach across geographical borders, the laws of transnational environments are also negotiated in relation to national practices and legislations. Yet the spaces of transnational digital media often tend to conceal the narratives – of nation, migration, language and culture, or personal experience – that undermine the narrative of technological and economic progress in much political rhetoric. For humanities research, as well as the literature and arts community, this poses challenges that cannot be tackled through established disciplinary frameworks or methodologies alone.

What must thus be considered is how the tensions between local, national, and transnational have prompted responses that, as Hudson and Zimmerman argue, recognize the geographies of digital media not only through “physical coordinates” but also in the sense of “aesthetic and ethical locations” (11). El Putnam’s digital video work Quickening explores the frictions between political discourse, official representation, and embodied everyday experience in the border region between the Republic and Northern Ireland, ahead of the possible return of the hard border dividing the island as the UK prepares to leave the European Union. By situating the pregnant body within a glitched, unstable, and almost unrecognizable landscape on screen, it also demonstrates how the border as a marker of the national domain relates to the experience of pregnancy and motherhood, as both are equally controlled by technology and nationalist discourse. Elaine Hoey engages digital-immersive space and game aesthetics to consider the calamities of alt-right nationalism and the refugee crisis. She considers how virtual game environments and platforms can be revealed to reinforce nationalist discourses, but can also be harnessed to challenge the manifestations and consequences of dangerous national exclusivity. Finally, Conor McGarrigle’s #RiseandGrind brackets the national as an explicit discursive framework, and instead addresses the transnational networked space itself through texts and interfaces that exist both within the networked domain of the web, and in gallery spaces situated in specific urban locations. McGarrigle’s work is thus situated in the same physical environments in which citizens encounter social media and other online platforms of global corporations. Each of these works manifests an unflinching awareness of the entangled relationship between embodied or situated experience, and the ethics and the aesthetics of 21st century transnational media environments. They all share a preoccupation with the tensions between geographical and material locations, and the manner in which literal and figurative borders, and their manifestations, are often rendered invisible in the technological environments and media interfaces that increasingly direct and inform the present-day experience.

In the context of Ireland’s literature and culture, and its global literary exchanges, Jahan Ramazani has stressed that it is important to recognize how the transnational is inherently neither beneficial nor problematic: as well as the emergence of transnational creative communities, and the resulting aesthetic exchanges and forms of dissemination, the term also relates equally to “both ethnic separatism and cross-cultural interchange, [and] global dialogue and imperial imposition” (339). Similarly, as digital media networks and platforms provide perspectives into both sides of the transnational, we need forms of critical creative practice that occupy the same spaces as the phenomena they critique, and that tackle corporate and political institutions from within, and from bottom up. In other words, the transnational global network economy calls for creative responses that render visible the structures and manifestations of the global economy and show how these structures are enacted at the level of national institutional frameworks, as well as through local, embodied experiences. As Ana Marques da Silva observes, “Electronic literature [seems] to be concerned with the suppressing of dichotomies between the global and the local, zooming in to the divergent and zooming out to the common, in a double movement able to encompass the contradictions of globalization,” yet it remains unclear how “the balance between the global and the local happens”, and how it is “possible to think of a glocal electronic literature” (da Silva n. pag). Consequently, inasmuch as electronic literature and art are frequently considered as forms of “transnational practice”, as da Silva also highlights, we must nevertheless account for their continuing emergence within geographical locations and institutions that exist within the national sphere.

In addition to geographical or national borders, media environments and infrastructures create, enact, and often coincide with, boundaries and divisions between individuals and communities based on class, ethnicity, race, or citizenship. Hudson and Zimmerman have argued in the context of transnational environments of digital media that

Digital divides raise questions about the ability to produce and distribute information. Webpages with content in local languages about local topics from local perspectives or applications that function according to cultural considerations […] cannot be universalized. […] One side is limited by access, another challenged by overconfidence in its own interpretation of access, another truncated by short-sightedness of corporate appropriations and hacks, and still another reduced by uncritical acceptance of intellectual property regulations. (Hudson and Zimmermann 9)

National institutions, including academic institutions, are key in determining individuals’ and communities’ “ability to produce and distribute information”, also by providing the frameworks within which digital humanities research and scholarship continues to take place.3 Considering electronic literature and art under the rubric of digital humanities research directs attention from technology primarily as a tool for accessing, storing, and disseminating various forms of cultural production, and towards the knowledge-producing aspects of communications technologies themselves, by making visible how they shape the sociocultural domain.

Creative practice in electronic literature and art also offers an alternative for digital humanities as a methodology primarily perceived as suited for the collection and preservation of national, if rarely explicitly nationalist, memory. As O’Sullivan et al. have argued, in the Irish context research has been characterized by a perceived emphasis on various manifestations of cultural identity, and the term “public humanities” may be more appropriate for describing how public interest in national history, culture, and heritage has informed many of the most extensive digital humanities projects carried out in Irish universities (n. pag.). Considerable financial investments have been made to promote digital arts and humanities internationally, and Ireland is no exception. In 2011, Ireland’s seven biggest universities launched a joint Digital Arts and Humanities structured PhD programme, described as being “the world’s largest programme of its kind” (“World’s Largest Digital Arts and Humanities PhD” n. pag.). The program’s stated aim was “to make a major contribution to the development of Ireland’s smart economy” (n. pag.), rather than the fostering critical perspectives to the manifestations of this economy. The rhetoric thus emphasized digital humanities as situated at the intersection of cultural specificity and cultural production. As Trish Morgan has argued, it is such a boosting of the national economy that has been seen as a key task for creative practice in the digital domain. It has also been linked to a wider political strategy of attracting multinational ICT corporations to the country, with low corporate tax rate and an educated workforce. Morgan argues that “[c]oupled with the ‘arts-as-rescuer’ discourse exist discourses around the so-called ‘smart’ or ‘knowledge’ economy, where policy documents foreground vague notions of ‘innovation,’ ‘digital’ and ‘creativity’ as potential saviours to Ireland’s economic woes” (Morgan 148).

The danger of this kind of coinciding of scholarly methodological frameworks, and national or cultural creativity with economic impact, is that it may fail to recognize what remains excluded, or outside the borders of the “imagined community” famously coined by Benedict Anderson, and account for those “cartography-traversing” exchanges that also shape the darker underbelly of national or cultural self-definition. In Ireland, digital humanities has most prominently been visible in the burgeoning of digital archives and databases of national and cultural significance, like in the Letters of 1916 project,4 or other digital archives and databases arising from similar projects in individual institutions, including for example the Abbey Theatre Digital Archive at the National University of Ireland, Galway (see Abbey Theatre), The Irish Poetry Reading Archive (see Irish Poetry Reading), or countless other digital resources focusing on the work of individual Irish authors or cultural institutions. Literary studies projects dominate this kind of digital humanities research, and undeniably these projects do important work in the collection, preservation, and critical study of cultural memory in a specific national context. The kind of creative practice that the works discussed here represent, however, is often carried out within disciplines that are not statedly or explicitly “literary”, though frequently more openly socially and politically charged than the projects identified as electronic or born-digital literature that have been carried out in Ireland in recent years. 5 The artists themselves have also commented on the political dimensions of their work. Putnam highlights how “female reproduction” had been “heavily contested” in Ireland as well as elsewhere (“Performing Pregnant” 207), and how medical technology leads to the framing of pregnancy through “political legislation and religious agendas” (210). Similarly, in her work, the Irish border exists as cartographically and politically determined abstraction. Elaine Hoey’s art mods, partially informed by nationalist politics in Ireland and by her experience as a mother to a son interested in gaming, address the “nationalist ideologies that are being sold to young males through videogames” (“Conversation” n. pag.). McGarrigle writes about the possibilities of “using data (open or otherwise) as a tool of political critique within an art context” (“Augmented Resistance” 108).

The works discussed here are thus ethically as well as aesthetically attuned interventions in the often unacknowledged structures informing the circulation texts, images, and narratives in the network economy. But they also adopt approaches that they share with numerous electronic literary projects from outside Ireland. Not only disciplinary boundaries, but also the boundaries between established art forms are in motion in digital and networked media environments; Rettberg stresses how in considering electronic literature, we must recognize that “there is significant crossover with a range of other disciplines, including fine arts, design, computer science, film, and communications” (128). The use of the term “digital arts and humanities” rather than “digital humanities” in the Irish context also signals a degree of recognition as to how creative arts are, at least to some extent, accepted as included in the field of digital humanities in the country’s higher education research environment (see O’Sullivan et al n. pag.). Most importantly, instead of adopting transnational media platforms as tools for celebrating national culture, they participate in locally as well as globally informed discussions on the tensions between local, national, and transnational aspects of technological change.

Despite the official rhetoric emphasizing national economy and growth, there is no denying that the availability of funding for early career researchers and practitioners in the field has also fostered critical work in the area of electronic or born-digital literature and art, by scholars and practitioners seeking to draw attention to the social, political, and economic implications of digital technologies themselves. The three practitioners whose work is discussed below have similarly developed their practice in academic contexts, as well as within the creative arts community. El Putnam is a lecturer in Digital Media at NUI Galway, Conor McGarrigle is a researcher and lecturer in Fine Art at the Dublin School of Creative Arts in TU Dublin, and Elaine Hoey, while not employed in higher education, recently graduated with a BA and MA in Fine Art Media from National College of Art and Design, Dublin, and has produced much of her recent work in conjunction with her studies for these degrees. None of the three artists explicitly state that they would be working within “digital humanities”, yet their work emerges from the same institutional frameworks that foster digital arts and humanities research in the more widely used sense of “an application of digital tools to a traditional form of humanities research”, as Scott Rettberg has phrased it (Rettberg 127). As “experiments in the creation of new forms native to the digital environment” (Rettberg 127), however, they subject technological tools and platforms themselves to scrutiny, and are informed by humanities research questions arising from complex social, cultural, historical, and political processes.

El Putnam: bodies and borders in Quickening

Putnam’s Quickening combines digitally manipulated landscape photography from the border region between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, and performance focusing on the embodied experience of pregnancy. The artist herself notes how

Landscape images are obscured through digital manipulation, where not only the territories of North and South merge through the photographic form of the landscape, but the shifting pixels emphasize the slippage of place in the border region. Bodies manipulate these images and sound through a motion sensor in order to highlight the human presence of this region, which constitute more than national and political divisions, but are home to communities with a particular history that relate to the contested space of the border. (Putnam, website n. pag.)

The embodied human presence in the landscape is reflected in the use of the term “quickening”, which refers to “the movements of fetus in early pregnancy”, and how “[t]hese sensations can only be experienced in the physical state of pregnancy: they are internal, haptic, and also phenomenological, making the pregnant woman the communicator of experience” (website, n. pag.). The artist also explicitly links the work’s themes and location to the discourses informing Brexit, and how the political rhetoric concerning Ireland’s border region entirely tends to disregard the experience of being in this landscape, similarly to the way in which women’s first hand experience of pregnancy has been marginalized by over-reliance on technological imaging: “The notion functions as an apt metaphor for the border, which encompasses a phenomenological quality that is experienced affectively and cannot be simply reduced to a line on a map” (website n. pag.).

During the performance of Quickening, Putnam’s own pregnant body interacts with the pixelated, jolting and glitchy landscape images on screen. The video of this performance on the artist’s website shows her overlaid and semi-transparent silhouette, which moves slowly and steadily forwards and backwards across the jolting images: the human figure simultaneously is, and is not, a part of the landscape as the moving and erratic images do not allow for a meaningful, embodied engagement with the space they depict (Figure 1).

Quickening is thus a non-verbal addressing of landscape as technologically mediated cultural and the national narrative, or the narratives that have also historically informed the contested border between the Republic and Northern Ireland, or Ireland and the UK. Similarly to how the fetus remains invisible to the naked eye in the early stages of pregnancy and can only be felt as the embodied experience of the pregnant woman herself, the Irish border cannot be seen in the terrain in which it is situated, but only encountered through everyday practices responding to political, national and cultural texts, and narratives.

Crucially, Putnam’s work not only combines creative practice with scholarly and critical writing, but also extends from the extremely personal and intimate domain to the public space of performance and dissemination, as well as to academic discourse within the institutional frameworks of higher education. In her scholarly work, she has highlighted the role of art and performance in challenging the prevailing institutional rhetoric, as well as the cultural and technological framing of pregnancy and childbirth. In the context of the Republic of Ireland, the constitution assigns women a “life within the home”, and states how “labour” outside the domestic sphere could risk women to “neglect of their duties in the home” (“A Life within the Home” 61). To counteract this rhetoric, she demonstrates how her own work and “the art of [other] mother performance artists in Ireland can function as resistance” (63). As well as the specific challenges of the Irish situation, culture, and legislation, including those presented by the recently repealed 8th amendment to the constitution (which banned abortion by equating the life of the unborn with that of the mother), Putnam’s creative and scholarly work highlights how discourses around women’s experiences of pregnancy and maternity can be placed within a wider framework whereby “advances in antenatal technology contribute to the progressive alienation of the mother-to-be from pregnancy and birth” (“Performing Pregnant” 208). This extends to the visual imagery of pregnancy, in which “ultrasound images focus on the foetus, visually circumventing the woman, with the womb functioning as a shadowed container” (208). Here, technology is given a role which perpetuates the imagery of pregnant women as vessels, “placing the pregnant woman in what Heidegger refers to as standing-reserve, delivering the ideology of Christianity through the iconography of the bump” (“Performing Pregnant” 212).

The present discussion, however, is focused on how in Quickening Putnam addresses questions of aesthetics, technology, and historical discourses of maternity as they manifest themselves in the specific location and specific sociocultural setting of the border landscape between the Republic and Northern Ireland. The border encompasses a national territory within which religious dogma, cultural nationalism, biopolitics, and medical technology colluded, until 2019, to deny women basic sovereignty over their own pregnant bodies. As situated digital artwork, Quickening can, as Søren Pold has argued “be seen as an allegory for the environmental hiding of the metainterface, including how it potentially controls humans, bodies and gender” (Pold 79). As such an allegory, Putnam’s project highlights the textual-technological control of the phenomenological and non-verbal experience. Pold observes how, by visualizing embodied, non-verbal phenomena, her work demonstrates that “[when] the borders and control interfaces become invisible and ‘soft’, they may lose the user dimension of being readable and subject to interactive manipulation, but they do not disappear from experience or lose the aspects of control” (Pold 79). It is nevertheless impossible to address Putnam’s choices related to technological medium or aesthetics without considering the manner in which they allow for an engagement with a specific geographical, material, embodied, and cultural situation: the glitch aesthetics of the digital landscape images draws attention to their own materiality, and how in traditional and official landscape imagery (including cartographic imagery) it is bracketed and harnesses to foreground a disembodied, politicized discourse. In this respect, there is a close affinity between media technology’s role in addressing pregnancy, and its addressing embodied experience of physical landscape. From the perspective of digital humanities practice and research, Quickening targets the same technological medium that enables its existence.

Elaine Hoey: no averting gaze

In her 2019 solo exhibition Surface Tensions at the Centre Culturel Irlandaise in Paris, Elaine Hoey exhibited two works created during the preceding three years: The Weight of Water (2016) and Animated Positions (2017). Both projects use game animation aesthetics, and combine audiovisual and verbal (voiceover narrative and text) elements. The artist also repeatedly underlines how these thematically linked exhibited works are to some extent informed by her understanding of the Irish manifestations of global, transnational challenges. A key feature shared by The Weight of Water and Animated Positions is the manner in which they appear highly abstract and lacking in specific markers of geographical or cultural setting: while highly politically informed and responsive to contemporary events in an identifiable manner, their “Irish” dimensions only explicitly emerge in paratextual material: in biographical information, interviews with the artist, or in institutional presentational settings (the locations of her exhibitions in Ireland and the Irish cultural center in Paris). Hoey has reassessed her own attitudes towards nationalism in the context of Irish society, Northern Ireland’s civil rights movement, and the related awareness of the political dimensions of Irish cultural production, as her perspective has widened from personal and local contexts to the manifestations of white nationalism fuelling Brexit, Donald Trump’s presidency, or the recent expressions of anti-immigration sentiment in Europe (“Conversation” n. pag.). For Hoey, transnational gaming networks and aesthetics thus offer a platform for addressing the complicated relationship between local circumstances and their global underpinnings.

The Weight of Water focuses on the human destinies tied to cross-border migration. It is “an interactive virtual reality installation which appropriates gaming technology to explore the current refugee crisis” (Hoey, website n. pag.). The artist describes how “[t]he work places the viewer in a central role, as both performer and witness in this 360° immersive narrative. Words and sound create an abstract visual landscape as the viewer navigates a difficult boat journey made by refugees as Europe begins to close its borders to those seeking asylum” (Hoey, website n. pag.; see Figure 2). In interviews, Hoey has underlined the importance of her choice of an immersive VR platform for the project: in a virtual reality environment, it is impossible to “avert your gaze” from the uncomfortable encounters and the unfolding events (Hoey, “Conversation” n. pag.; Hoey, Interview France24 n. pag.). Rather than empathy through the replication of first-person visual perspective, where VR’s particular potential has occasionally been seen, Hoey’s own words underline immersive virtual environment’s potential for uncomfortable proximity, close witnessing, and invitation for solidarity.

Ireland’s role in the 21st century refugee crisis is tied to its transnational reach, but also manifests itself through specific local phenomena. Due to its geographical location and sea borders, the island of Ireland has received a very small number of refugees when compared to many countries in continental Europe. Hoey stresses how Ireland has largely assumed the position of observing the refugee crisis from a distance, at a remove from the actual locations of these human tragedies:

We in Ireland were quite removed from this crisis, both in taking refugees but also in our own experience of it, so a lot of our content was coming across the news, and I wanted to somehow collapse that distance, and allow the person to become […] completely immersed in a world that was quite scary, quite frightening. (Hoey, Interview France24 n. pag.).

In the case of The Weight of Water, Hoey stresses her unease with the idea of an artist, an outsider, seeking to accurately represent the refugee experience, or the cultural experience of those fleeing Syria, for example. This is reflected in how The Weight of Water, as well as Animated Positions, is focused on specific themes and phenomena, but stops short of purporting to explain or intimately know any particular cultural experience, or point of view. Instead, in The Weight of Water Hoey adopts an aesthetics that aims at “collapsing [the] distance” between news media reports and stories of refugees making the perilous sea journey to Europe, and the visual environment of those putting their lives at risk in the attempt.

A sense of apprehension when it comes to the contradictions between media reports and their aesthetic representations of the refugee crisis, and the embodied situations in which refugees find themselves, has also informed a number of other works of electronic literature. In “Migrating Stories: Moving across the Code/Spaces of our Time”, Anna Nacher considers how transmedia practices have been harnessed to tackle migrant experiences to “[bridge] ontologically different realms” (Nacher n. pag.). But where Nacher’s discussion focuses on the use of data and data visualization in relation to narratives emerging in networked space, The Weight of Water invites a close encounter with destinies of the refugees in an imaginary, virtual space, less as storytelling than as an implied presence. A female voice, speaking in accented English, addresses an undefined “you”: “You prepared to join us in the shadows, but you didn’t. Perhaps something in our silence stopped you. Or perhaps, something in our shadows. As if the bodies that had cast them had already vanished” (Hoey, “Weight of Water” n. pag.). In the virtual space of Hoey’s work, however, bodies are visible, and too close to ignore. For the viewer, the experience highlights the failure of many Western citizens to see or acknowledge the darkness of the journey from which many will not re-emerge. The addressing of the second person “you” in an interactive game environment thus invites participation and interactivity through choice, but also raises questions regarding culpability. Such a second-person perspective is also adopted in the “playable story” Salt Immortal Sea by Joseph Ken, Mark Marino and John Murray, which “places the interactor in the position of the refugee” (Ken, Marino et al. n. pag.). Unlike Hoey’s work that plays on verisimilitude, the imagery in Salt Immortal Sea is highly stylized, and the characters are presented as figures modeled after those in ancient Greek art: as black silhouettes against a bright colored background, pointing towards the mythical narrative of the Odyssey that underpins the narrative. Through their chosen aesthetics, these two works thus make very different kinds of appeals to their addressee: where Salt Immortal Sea presents a somewhat disturbing contrast between the playful game narrative and its real-world referent, Hoey places her viewer awkwardly close to the human figures sharing the narrative virtual environment.

In human rights discourse, much discussion has concerned the question of empathy, and human rights organizations have sought to harness the potential of computer games and their interactive structures to move away from “[t]he passive contemplation of the image of the starving African child” to “the possibility to create, move, and direct her avatar, to ‘experience’ what she experiences”, as Sophie Oliver writes (Oliver 94). Whether such approaches can indeed evoke empathy has been questioned, however, and associating “games” and “play” with the very real, embodied experiences of the victims of human rights violations can also be deemed highly problematic. As Oliver argues, “the virtual world of social interactivism is a utopia plagued by moral ambivalence, with the appropriateness of quite literally playing at mass human suffering seen as fundamentally suspect” (94).

But Hoey is less concerned with the replication of another’s experience, than with the possibilities of perspective and immersive virtual space, and the manner in which they force the viewer to discard the comfort of observation from a distance. Like many digital authors and artists, she demonstrates an acute awareness of the importance, and the ethical dimensions, of the relationship between the reader/viewer/listener/player, and the unfolding narrative. For Hoey, the immersive virtual environment does not make us feel the other’s pain as our own, but instead denies the possibility of withdrawing to a distance that allows for detachment. This is the situation with “flat screen” or flat page view of conflicts and human rights violations, which can place reporting on the victims of conflicts and disasters between items focusing on entertainment or economy, or even advertisements. As an example, Hoey mentions an illustration included in John Berger’s Ways of Seeing (1972), where a page of The Sunday Times presents a picture of refugees from Bangladesh above an image, of the same size, of a woman in a bath towel gazing at a man outside her window, advertising bath soap (see Berger 152). If, in “transnational environments […] physical and bodily location simultaneously matters and does not matter”, as Hudson and Zimmerman observe (10), the transnational aesthetic of gaming environments can be harnessed to address this ambiguity, and to ask audiences consider their own situated responses to geographically distant events.

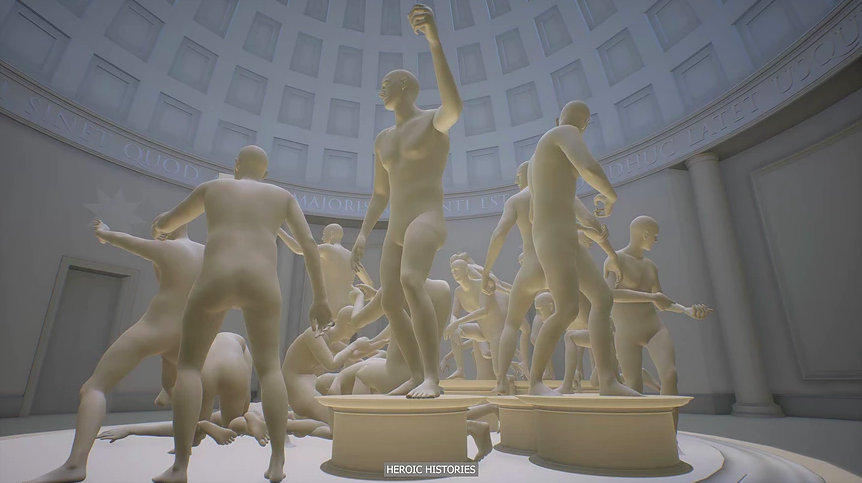

Similarly to The Weight of Water, Hoey’s Animated Positions repurposes a gaming platform and aesthetics, as it combines the nationalist themes and motifs of 19th century paintings, and the dynamics of contemporary video game environments in a remodeled version of the first-person shooter blockbuster game Call of Duty. The work’s virtual space is the white interior of a stylized Pantheon-style rotunda and dome. Hoey describes the work as follows:

[It] draws reference from 19th century European nationalist paintings and explores the role of art in the portrayal of jingoistic patriotic ideals that have become culturally symbolic in the formation of the nation state. This piece re-animates the war like stances and positions of bodies found within these paintings, using character animation taken from the video game Call of Duty. The work challenges notions of nostalgia for the nation state, creating a contemporary critique of the underlying violence that underpins much of today’s nationalistic ideologies. (“Animated Positions” n. pag.) (See Figure 3)

There is also a verbal/textual element in the work, in the form of subtitles, also written by Hoey, at the bottom of the view. Hoey characterizes the text as “quite abstract”, “like a poem”: there is no narrative, and there are no details that would specify nationalism in the context of some particular culture or nation state. Instead, the text repeats phrases and words that reflect the recurring motifs and ethos ofnationalist discourse: “HEROIC HISTORIES”, “PRESERVING NATIVE GROUND”, “HOUSING MAJESTIC ARCHITECTURE”, “GRAND STATUES OF OLD”. Some of the text is presented as dialogue, between “he” and “they”: “I WANT TO BUILD YOU A MONUMENT HE SAID”, “TO WHAT? THEY SAID”, “GLORY! HE SAID”; “TRADITION? THEY SAID”, “YES HE SAID”.Yet most of the text cannot be attributed to any specific speaker, or to one or other side of the dialogue. Like the white figures slowly shifting their positions, the geographically and historically decontextualized phrases appearing at the bottom of the view point to the ideas, metaphors, spaces, and materials through which European nationalism has been articulated.

In addition to the subtitles, text appears in the frieze of the rotunda, which includes a quotation from the prophecies of the 16th century botanist, alchemist, occultist, and physician Paracelsus, collected in Prognosticon Theophrasti Paracelsi:

QUOD UTILIUS DEUS PATEFIERI SINET, QUOD AUTEM MAJORIS MOMENTI EST, VULGO ADHUC LATET USQUE AD ELIÆ ARTISTÆ ADVENTUM, QUANDO IS VENERIT (“God will permit a discovery of the highest importance to be made, it must be hidden till the advent of the artist Elias”)

Arthur Edward Waite has suggested that “prophecies of this character […] are interesting evidence that then as now many thoughtful people were looking for another savior of society” (Waite 34). Similarly, according to Walter Pagel, the reference to “Elias” was connected to the idea of future “enlightenment and happiness” that would “descend upon the future generations and lift the veil of obscurity which still blinds him and his age” (Pagel 6). 6 Hoey does not comment on the choice of this quotation, but its effect seems twofold: the utopian, yet nostalgic search for an ideal nation that would eradicate the fear and insecurities of a complex world in crisis on the one hand, and, on the other, the possibility or art as socially attuned (if not politically conditioned) practice to tackle the darker underpinnings of nationalism. The viewer encounters Paracelsus’s words as circling the animated statue-like figures on their pedestal, and the Latin inscription of the visual-textual frame further emphasizes the figures as aesthetic manifestations of contradictory aspects of European heritage: a search for knowledge, human value, and new forms of enquiry, but also a historical legacy of imperial conquest, colonization, and nationalist conflict. The history of scholarship – and the legacy of Latin as a lingua franca of higher learning – is implicated as a participant in the emergence of nationalism, but also as a possible location for its critique. Academic knowledge’s enlightenment claim for universalism and objectivity through abstract philosophical discourse is the poison, but can be appropriated to consider a cure.

Consequently, within its virtual game world, Animated Positions presents the figures, their movements, and the work’s underlying rhetoric in highly abstract terms. The work highlights how nationalism, paradoxically, glorifies the unique essence of a community emerging from “native ground” (a phrase appearing in the text) of a particular nation, yet does this by adopting aesthetic motifs, rhetorical devices, and narrative forms that are shared across specific different national boundaries. The idea of the nation state crosses borders to manifest itself in recurring and recognizable guises, regardless of the specific nation represented. In an interview, Hoey describes how her work responds to the “majestic” space of the Louvre in Paris in which the 19th century paintings, too, are place, but how her work was simultaneously informed by her own, increasingly problematic feelings towards nationalism in the Irish context, as such paintings and images could also be found in the National Gallery in Dublin (Conversation n. pag.). For Animated Positions, Hoey used a “100 percent white” modded version of Call of Duty (“Conversation” n. pag). As well as the figures, the flag they carry is white, and the scene is almost like a blank canvas on which any chosen national imagery could be projected. Thus, while Hoey stresses that this whiteness also signifies the racialized whiteness of nationalism in the European and American contexts (“Conversation” n. pag.), the white colour also appears as synonymous with “blank”: the dangerous ideal of racial and racist purity that alt-right ideology promotes can exist only in abstract.

Unlike Putnam’s at once figurative and material maternal body, situated in the specific location of the Northern Irish border landscape, Hoey’s figures are entirely detached from actual, embodied terrains. Instead, for Hoey, the gaming community practice of modding allows for a foregrounding of the political aesthetics of virtual game environments, which are also geographically decontextualized. She is highly aware of how, in these often male-dominated communities, some socially and culturally problematic aspects of gaming culture become accentuated: for example, modders often “ethnically cleanse” the characters in the modified game in a highly problematic manner (“Conversation” n. pag.). Hector Postigo, commenting on the modder community, observes how in interviews, one of the most commonly mentioned reasons for adopting this practice was that participants felt that “modding allowed them to identify with the games and […] tried to make games ‘their own’ by designing unique elements of game play or importing elements from popular or national culture that had some meaning to them personally” (Postigo 309). Postigo’s view of the process may be more positive, and focuses on the role of modding in the wider game entertainment economy, however it nevertheless highlights how national and nationalist aspects have a crucial presence in this gaming community and fan culture, as they did in the 19th century art world that also informs Hoey’s approach. Hoey’s statue-like characters thus demonstrate the paradox of the claim to a unique national character in white, European/Western nationalism, and its reliance on the transnational circulation and repetition of motifs and aesthetics. Rather than an approach to borders as complex, and often porous contact zones, nationalism is sustained by the idea of an imagined and exclusive center that can be demarcated as ethnically and socially distinct, and justified by cultural essence.

Against games and gaming as an area where “digital innovation” can take place with the goal of (indirect) financial boost for the entertainment industry, Hoey’s practice as a digital artist shows how virtual environments can be employed to tackle the ugly underbelly of nationalist ideology, an ideal purged of embodied material, social, and cultural experience. The transnational (if problematic) circulation of a nationalist aesthetics of multinational gaming and entertainment corporation is appropriated, but only as a way to critique its own ideological foundation.

Conor McGarrigle: art as resistance in the crisis economy

From two different perspectives, both Putnam and Hoey tackle the national and cultural manifestations of politicized bodies and borders, and the causes and consequences of exclusive – and often gendered – nationalist ideology. The work Conor McGarrigle, however, has been primarily focused on the discrepancies between situated local practices, and the operations of the global financial market and network economy. Rather than cultural-geographical centers and their boundaries, McGarrigle’s practice often inhabits the purportedly placeless domain of social media platforms and interfaces, and the invisible processes of data gathering and algorithmic determination that underpin them – this work, too, probes the operations of the by now all-encompassing metainterface (Andersen and Pold). In his previous work, he has engaged with Dublin locations and real estate transferred to Ireland’s National Asset Management Agency (NAMA) after the 2008 global financial crash and the resulting collapse of Ireland’s property market, with traffic networks and surveillance camera systems controlling urban space, and the possibilities of mobile storytelling through curated and localized data in urban space. As a lecturer in Fine Art at the Dublin School of Creative Arts, his research has been informed by an approach combining critical activism, creative practice, and scholarly writing, and a methodology frequently focusing on “data (open or otherwise) as a tool of political critique” (McGarrigle, “Augmented Resistance” 108). Such an approach foregrounds research-as-practice itself as a political act.

McGarrigle’s generative work #RiseandGrind, exhibited in several gallery spaces in Ireland and the US, and performed on the web by a Twitter bot, does not directly engage with any specific local setting or related content, though it implicitly comments on the situatedness of networked encounters through the locations of the exhibitions. According to McGarrigle,

#RiseandGrind is a generative installation that data-mines Twitter to capture millions of conversations, from Twitter hashtags (#Riseandgrind and #Hustle) chosen to represent a very specific filter bubble (embodied neoliberal precarity), which are used to train a recurrent neural network to produce a biased AI that generates text for a Twitter Bot that participates in social media discourse on 24/7 internet culture. (McGarrigle, website n. pag).

In a gallery installation, the machine-learning operation is portrayed on multiple screens, “presenting the process of machine meaning-making through various epochs with differing data-sets, setups and algorithmic parameters through a number of experimental iterations” (McGarrigle, website n. pag.). McGarrigle also stresses that his work highlights how “machine-learning processes are dependent on the quality and sentiment of the training data” (McGarrigle, website n. pag.). The data set training the algorithms is authentic,

…but one that reflects the filter bubble dynamics of its hashtags and as such is inherently biased, the text generated by the neural network amplifies this bias but does so in a way that creates and presents its own cohesive world view that is specific to the circumstances and parameters of its coding, reflecting the bias of the data and the assumptions of the algorithmic platform (McGarrigle, artist’s website, n. pag.).

The exhibition setting allows the audience not only to witness the mechanism behind learning process, but it also makes it possible to see how the tweets gradually evolve into readable texts reflecting the emphases, values, and moods of the economy from which they arise. This economy and its rhetoric thus become a self-perpetuating process, which amplifies its own biases through repetition with decreasing difference.

But while operating in the networked space of the web, #RiseandGrind has been exhibited in several gallery spaces in Ireland and America – in Dublin, Galway, and Detroit. Placed in an urban setting and a location with windows facing public space, the hashtag neon sign “#RiseandGrind” is visible to passers-by, even those not visiting the gallery intentionally. By alerting individual observers, only some of whom are visitors to the exhibition, to its existence, the project also invites them to participate in it by checking the hashtag through their own mobile devices and social media accounts. The project thus addresses, and simultaneously enacts, the processes combining embodied everyday experience in commercial urban space, set in a specific location, and the participation in the operations of transnational network capitalism through digital interfaces that hide their underlying operations.

In his scholarly work, McGarrigle has similarly tackled the question of the potential of creative practice to interrogate social and political phenomena. The Irish manifestations of the neoliberal network economy have been particularly frequently targeted in McGarrigle’s art projects, and he is cognizant of how

In our present moment we are witnessing an upsurge of artists who address and use the political economy as both subject matter and material. This rise of artistic production in response to financial crisis is in part an outcome of the long crisis of 2008, which is more sustained and global in its extent. (Lerer and McGarrigle 5).

In such a system, artists, researchers, and authors, too, must develop means to consider the connections between specific events and experiences in Dublin, Galway, Detroit or elsewhere, and the processes by which they relate to, and feed into, each other. The aftermath of the 2008 crash, which was triggered by the Lehman Brothers collapse, is still felt in everyday life in Ireland: “Increased contagion between local crises in a hyper-connected global financial system means that crises are more likely to cascade beyond local economies becoming a permanent feature of economies with repercussions felt in all aspects of everyday life” (Lerer and McGarrigle 5).

A critique of such hyper-connected systems, cascading effects, and everyday experiences of life under constant pressure must take place through the same system; McGarrigle’s use of a combination of algorithmic machine learning, the commercial social media platform Twitter, and locally situated and visible gallery spaces allows for the work to perform itself in the same environments that it addresses. His creative work reflects the view that “[o]ne of the many roles that art practice maintains in financial crisis and within the global market and capitalist systems is to expose the workings of it and offer alternatives that are entirely reasonable, even if only at the speculative level” (Lerer and McGarrigle 8). Consequently, through works such as #RiseandGrind, McGarrigle considers the relationship between everyday experience, material locations, and the invisible processes of data circulation, accumulation, and commercialization. His approach is akin to the phenomena that Hudson and Zimmermann consider as characteristic of transnational media environments:

The interfaces between physical computing and the “virtual world” complicate our sense of space and place. Digital media is often accessed via digital networks, presenting opportunities as well as limitations in conceiving new or alternative forms of collaborative knowledge production (9).

Such an approach moves beyond any simplistic approach to digital technologies and networks as primarily utopian or dystopian, but rather considers existing frameworks through a combination of critique, and the envisioning of “alternatives” through speculative creative practice. This practice complements and enacts ideas expressed in its author’s scholarly and institutionally framed work.

Conclusion

What these projects of all the three practitioners discussed here demonstrate is that to tackle the problematic manifestations related to national and geographical boundaries, institutional and political rhetoric, and transnational economic processes, higher education institutions have a crucial role in fostering digital arts and humanities tools as a form of social and cultural critique. Creative practice in its various guises in the fields of electronic literature and art, is needed to develop aesthetic approaches and forms of expression suited for the specific challenges presented by transnational exchange networks, manifesting themselves through local, everyday encounters. This is “innovation” that operates in real time, alongside the evolving technologies that shape and change our society. And while top-down political control of bodies and places may follow the legislation of a single nation state, it is communicated and realized through technological infrastructures and platforms that operate across any national boundaries. The experience of motherhood may change radically at the crossing of an international, yet invisible border. The multinational gaming industry promotes design practices and environments that lead to polarized and violent divisions between refugees and migrant communities, and an aggressive culture of right-wing, racist nationalism. Citizens – including those working in higher education – struggling under the growing pressures of the trickle-up economy and network society participate in these networks from ground level in Dublin, Galway, Detroit, and elsewhere, where they must find situated responses to the demands of 24/7 online capitalism. All of these phenomena require a transformation of established forms of scholarly research and practice, and existing disciplinary borders and methodologies. Academia, too, is embedded in the digital society, and has a responsibility to evaluate its place in it critically.

Finally, that none of the above artists and researchers describe themselves as working in digital humanities specifically is a demonstration of how the concept of digital humanities in Ireland, too, is still largely applied within the traditional disciplinary sphere, and as the application of new technological tools to various humanities research questions. There is a need to widen the framework to consider such projects as forms and methods for engaging in humanities research. In literary studies in particular (often used interchangeably with “English”, itself a problematic equation of a particular majority language or tradition, and literary studies more generally) digital tools and platforms are still less often the focus of critical inquiry than methods for approaching more established topics. And, despite the emergence of some notable exceptions in recent years, 7 “digital literature” is still frequently used interchangeably with “digitized literature”. But as borders between different media environments blur in the digital network economy, this also presents a scholarly and institutional responsibility to renegotiate the borders between different art forms (verbal, visual, oral, aural, performative) and the disciplines that have emerged around them, and to recognize how narratives, motifs, imagery, and design practices circulate in digital interfaces. The work of Putnam, Hoey, and McGarrigle presents a more pronounced, and recalibrated engagement with the “arts” dimension of research and practice within “digital arts and humanities”.

Works Cited

Abbey Theatre Digital Archive. National University of Ireland. https://library.nuigalway.ie/collections/archives/depositedcollections/featuredcollections/abbeytheatredigitalarchive/. Accessed 10 Jul 2020.

Berger, John. Ways of Seeing. London: Penguin, 2008 (1972).

da Silva, Ana Marques. “Zoom In, Zoom Out, Refocus: is a Global Electronic Literature Possible?” Hyperrhiz: New Media Cultures, no. 16, 2017. http://hyperrhiz.io/hyperrhiz16/essays/1-da-silva-world-elit-possible.html. Accessed 25 Aug 2020.

“Digital Arts and Humanities (DAH) Structured PhD Students 2011-2016”, Royal Irish Academy Website,https://www.ria.ie/digital-arts-and-humanities-dah-structured-phd-students-2011-2016. Accessed 29 Sep 2019.

“Elaine Hoey, Surface Tension: Conversation with Helen Sharp”, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=63q9vXjmBMc. Accessed 10 Jul 2020.

Gallagher, Mary. World writing: poetics, ethics, globalization. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2008.

Hoey, Elaine. “The Weight of Water”. Project web page. https://www.elainehoey.com/2-1. Accessed 10 Jul 2020.

---. “Animated Positions”. Project web page. https://www.elainehoey.com/animated-positions. Accessed 10 Jul 2020.

Hudson, Dale, and Patricia R. Zimmermann. Thinking Through Digital Media: Transnational Environments and Locative Places. Palgrave MacMillan, 2015.

Irish Poetry Reading Archive. University College Dublin. https://www.ucd.ie/specialcollections/archives/ipra/. Accessed 10 Jul 2020.

Joseph, Ken, Mark C. Marino, John Murray, and Joellyn Rock. Salt Immortal Sea. Digital Narrative, Illustration, Interactive Installation. _https://joellynrock.com/portfolio/salt-immortal-sea/. Accessed 30 Sep 2019.

Karhio, Anne. “At the Brink: Electronic Literature, Technology, and the Peripheral Imagination at the Atlantic Edge.” Electronic Book Review, 5 Apr 2020. https://electronicbookreview.com/essay/at-the-brink-electronic-literature-technology-and-the-peripheral-imagination-at-the-atlantic-edge/. Accessed 10 Jul 2020.

Kaur, Raminder, and Parul Dave-Mukherji, eds. Arts and aesthetics in a globalizing world. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2015.

Lerer, Marisa and Conor McGarrigle. “Art in the Age of Financial Crisis,” Visual Resources: An International Journal on Images and Their Uses, special issue “Art in the Age of Financial Crisis”, vol. 34, no. 1-2 (2018): 1-12.

Lynch, Claire. Cyber Ireland: Text, Image, Culture. Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan, 2014.

McGarrigle, Conor*. #RiseandGrind.* Artist’s website. _https://www.conormcgarrigle.com/riseandgrind.html. Accessed 10 Jul 2019.

---. “Augmented Resistance: The Possibilities for AR and Data Driven Art + Interview, Statement, Artwork,” Leonardo Electronic Almanac, vol. 19, no. 1 (2013): 106-115.

Morgan, Trish. “Sharing, hacking, helping: Towards an understanding of digital aesthetics through a survey of digital art practices in Ireland.” Journal of Media Practice, vol. 14, no. 2 (2013): 147-160.

Nacher, Anna. “Migrating Stories: Moving across the Code/Spaces of our Time”, Hyperrhiz: New Media Cultures, special issue “Other Codes / Cóid Eile”, no. 20 (2019). http://hyperrhiz.io/hyperrhiz20/. Accessed 30 Sep 2019.

O’Sullivan, James. “Electronic Literature in Ireland.” Electronic Book Review, 11 April 2018. https://electronicbookreview.com/essay/electronic-literature-in-ireland/. Accessed 10 Jul 2019.

O’Sullivan, James, Órla Murphy, and Shawn Day. “The Emergence of the Digital Humanities in Ireland.” Breac: A Digital Journal of Irish Studies, 7 Oct 2015. https://breac.nd.edu/articles/the-emergence-of-the-digital-humanities-in-ireland/. Accessed 10 Jul 2020.

O’Toole, Fintan. The Lie of the Land: Irish Identities. Verso, 1997.

Pagel, Walter. “The Paracelsian Elias Artista and the Alchemical Tradition.” Medizinhistorisches Journal, vol. 16, no. 1-2 (1981): 6–19.

Putnam, El. Quickening. 2018. Project description and video. Artist’s website. http://www.elputnam.com/quickening.html. Accessed 10 July 2019.

---. “Performing Pregnant: An Aesthetic Investigation of Pregnancy,” in New Feminist Perspectives on Embodiment, edited by Clara Fischer and Luna Dolezal. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

---. “Not Just ‘A Life Within the Home’: Maternal labour, art work and performance action in the Irish intimate public sphere,” Performance Research: A Journal of the Performing Arts, special issue ‘On the Maternal’, vol. 22, no. 4 (2017): 61-70.

Postigo, Hector. “Of Mods and Modders: Chasing Down the Value of Fan-Based Digital Game Modifications,” Games and Culture, vol. 2, no. 4 (2007): 300-313.

Ramazani, Jahan. “A Transnational Poetics.” American Literary History 18, no. 2 (2006): 332–59.

Waite, Arthur Edward. The Real History of the Rosicrucians. Cosimo Classics, 2007.

“World’s Largest Digital Arts and Humanities PhD Programme Launched to Facilitate Smart Economy”, Trinity College Dublin website, 18 Nov 2011, https://www.tcd.ie/news_events/articles/worlds-largest-digital-arts-and-humanities-phd-programme-launched-to-facilitate-smart-economy/. Accessed 29 Sep 2019.

Footnotes

-

While Northern Ireland, consisting of six counties of the island’s northernmost province of Ulster, is also addressed where relevant, the question of national institutional frameworks will here be addressed from the perspective of the Republic specifically. ↩

-

For a more detailed discussion on the topic, see Karhio, ”At the Brink”. ↩

-

I would like to thank Jessica Pressman for drawing my attention to this phenomenon during the project workshop discussions in Berkeley, California. ↩

-

The Letters of 1916 was a project that built a crowdsourced archive collecting letters connected to the 1916 Easter Rising during the centenary of the event (see Letters). ↩

-

For an overview on Irish electronic literature, see O’Sullivan. ↩

-

I want to thank Giuliano d’Amico for his help in addressing the significance of the quotation from Paracelsus. ↩

-

See e.g. the generative piece Eververse by Justin Tonra, the publisher of electronic literature New Binary Press run by James O’Sullivan, the born-digital poem Holes by Graham Allen, or the body of works of electronic literature by Michael J. Maguire. ↩

Cite this article

Karhio, Anne. "Ethics and Aesthetics of (Digital) Space: Institutions, Borders, and Transnational Frameworks of Digital Creative Practice in Ireland" Electronic Book Review, 4 October 2020, https://doi.org/10.7273/z9s9-bd83