Language |H|as a Virus: cyberliterary inf(l)ections in pandemic times

While presenting a series of four selected E-Lit artworks, Marques and Gago demonstrate how our recent pandemic will affect new media art, similarly to the ways in which the Athens Plague affected the writing (and reception) of Greek tragedies. And the same goes for Cinema and Aids, smallpox and illustration, photography and the third bubonic plague, usw.

I have frequently spoken of word and image as viruses or as acting as viruses, and this is not an allegorical comparison. -William S. Burroughs

If the computer virus is a technological phenomenon cloaked in the metaphor of biology, emerging infectious diseases are a biological phenomenon cloaked in the technological paradigm. As with computer viruses, emerging infectious diseases constitute an example of a_ counterprotocol phenomenon. Alexander Galloway and Eugene Thacker, The Exploit

Linguistic Inflections

In Plague and the Athenian Imagination (2007), Robin Mitchell-Boyask considers the hypothesis of the Athens Plague being responsible for changes in the ways Greek tragedies came to be performed after 430 BCE. According to Mitchell-Boyask, not only the experience of living in a city ravaged by the plague was reflected in discourse, “the adjacency of the Asklepieion to the Theater of Dionysus was an important part of their performative environment after 420 and the construction of the Asklepieion itself was part of the Athenian reaction to the plague.” (Mitchell-Boyask 2007, 2).

To sustain his argument, Mitchell-Boyask refers to History of the Peloponnesian War, a narrative in which the Greek historian Thucydides presents a very detailed textual account regarding the effects of the plague in the city of Pericles. Full of rhetorical devices, in every known translation of this historical account, the original strain (Greek language) used by Thucydides is subject to new mutations. Nonetheless, in its essence, from the description of symptoms and ways of transmission to the process of creating immunity, through its narration, the Plague of Athens seems to hold what characterizes every pandemic, namely the overlapping of both physical and social malaise.1 Being a text known for its blurring of boundaries when it comes to genre categorizations, naturally, language may have something to do with it, for instance, the ways in which words are interpreted as subject to mutations, in fact, the very word “pestilence”:

Such then was the calamity that had befallen them by which the Athenians were sore pressed, their people dying within the walls and their land being ravaged without. And in their distress they recalled, as was natural, the following verse which their older men said had long ago been uttered: ‘A Dorian war shall come and pestilence with it.’ A dispute arose, however, among the people, some contending that the word used in the verse by the ancients was not λοιμός, ‘pestilence,’ but λιμός, ‘famine,’ and the view prevailed at the time that ‘pestilence’ was the original word; and quite naturally, for men’s recollections conformed to their sufferings. (Thucydides 1956, 355; our emphasis)

From Sophocles’ King Oedipus to Boccaccio’s Decameron, Shakespeare’s King Lear or Daniel Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year, the experience of different pandemics by these and other authors seems to add other layers of meaning to William Burroughs’ reflections on language as a virus, namely in their variations, changes, ambiguities, errors, accidents, and/or mutations. In fact, even for Burroughs, the expression seemed to have changed over time. Directly connected to his mastering of the cut-up and fold in techniques, the original strain, “the word is now a virus”, first surfaced in his 1962 fictional novel The Ticket that Exploded.2 As it laid the ground for his thoughts on technology as a means towards a social revolution, one of its variants came with Electronic Revolution, an essay from 1970 in which Burroughs states that his idea of word (and image) as viruses or “acting as viruses” goes way beyond the allegorical comparison, namely by understanding writing technology as an alien virus that goes undetected because it has a perfect symbiosis with its host (Burroughs 2005, 5). The virality of the expression, however, owes much to Laurie Anderson’s homonymous musical piece released in 1984, the same year that computer scientist Fred Cohen first used the term “computer virus” in a paper called “Computer Viruses-Theory and Experiments” and just a year after the identification of the HIV Virus as the cause of AIDS.

In view of this, if we are to recognize that language and viruses coexist with the experience and repercussion of every single pandemic, to what extent may the concept of virality suffer a new mutation by the influence of COVID-19, most particularly one that is specifically connected to digital media and the Internet?

Artistic Infections

For Boris Groys, “Modernism is a history of infections”. Expanding on Kazimir Malevich’s idea of artistic infection, in which the modernist painter compares the straight lines of Suprematism to the rectilinear organic form known as the bacillus of tuberculosis, just as the latter can modify its body, Groys tells us how, for Malevich, “novel visual elements introduced into the world by new technical and social developments modify the sensibility and nervous system of the artist” (Groys 2016, n.p.). However, according to Groys, from the moment Malevich applies the trope of biological evolution to artists and the teaching of arts, he subverts the logic of immunization inherent to the whole metaphor: instead of incorporating “new aesthetic bacilli, to survive them and find a new inner balance, a new definition of health”, artists “should not immunize themselves against these bacilli, but on the contrary, accept them and let them destroy the old, traditional art patterns.” (2016, n.p.)

Similar to Mark America’s Avant-Pop Manifesto, in which Amerika associates microorganisms, biochemistry and virulence to mainstream culture and “its dreadful disease (‘information sickness’) that infects the core of our collective life” (Amerika 1993), Groys draws a line of continuity from political movements, mass culture and consumerism to information technology, interactivity, and the Internet. As such, if being open to the exterior and “to become infected by Otherness” (Groys 2016) is part of what defines (post)modernism, ultimately, the Internet and its ecosystemic nature is to be understood as “a space suitable to the spread of contagion and transversal propagation of movement (from computer viruses to ideas and affects)” (Terranova, as quoted in Parikka 2010, XXIV).

The idea of hijacking the whole logic of the immune system of arts (and artists) is not far from the ways in which computer viruses and digital virality came to be understood by the end of the 20th century. In Digital Contagions, Jussi Parikka highlights that the notion of viral is infectious to the point of expanding “into various contexts from cybernetics and computing to biology, literature, television, cinema, and media art”, including “philosophical theory and cybertheory in the 1990s.” (Parikka 2016, 165). But, differently from Malevich’s metaphors of biological bacilli applied to arts, Parikka’s discussion on viruses, here paraphrased by Kim Knight, goes well beyond the allegorical, suggesting that “the digital virus is becoming-biological and that ultimately the biological deterritorializes and reterritorializes across different texts and contexts.” (Knight 2015, n.p.).

In this sense, while the notion of the virus is a trope of contagion that infects, contaminates, and mutates, from the moment it became associated, by affinity3, with digital media, it underwent a state of “becoming-biological” (to use Parikka’s expression), ending in a current state of an in-betweenness (Marques 2022, 3). Meaning that, as a permeable trope, through that in-between status, the word virus acts as an interface, across different fields of knowledge, thriving and multiplying in a host presenting the ideal conditions for the virulent and rhizomatic propagation of “Otherness”. Through language, not just understood as “communication or about thinking but a force that materially connects rhizomatically with its outside,” computer viruses are subject to “various assemblages of enunciation (such as mass media acts).” Consequently, harmful viruses can mean “malicious software, a security problem, but also a piece of net art, an artificial-life project or a potentially beneficial utility program” (Parikka 2016, XXVIII-XXIX), a complex definition4 that is not far from the ways in which virologists Mario Mietzsch and Mavis Agbandje-McKenna talk of the “good that viruses do”, understanding the potential of viruses for the development of “useful biologics with therapeutic benefits to humans.” (Mietzsch and Agbandje-McKenna 2017, 1).

Accordingly, for them,

If a survey were to ask nonvirologists for their opinions about viruses, the word “good” would be unlikely to arise. Instead, words such as “disease,” “infection,” “suffering,” or “life-threatening” would likely dominate, as people primarily think of viruses such as HIV, Ebola virus, Zika virus, influenza virus, or whatever new outbreak is in the news. However, as we are now finding out, not all viruses are detrimental to human health. In fact, some viruses have beneficial properties for their hosts in a symbiotic relationship, while other natural and laboratory-modified viruses can be used to target and kill cancer cells, to treat a variety of genetic diseases as gene and cell therapy tools, or to serve as vaccines or vaccine delivery agents. (1)

The idea of the “good” virus, however, is not limited to virology. In The Exploit, an experimental volume made of nodes and edges, Alexander Galloway and Eugene Thacker explore the transversality of “the good-virus concept” in/to a series of domains. Central to their argument is the notion of networks, understood as “aggregate interconnections of dissimilar subnetworks” (Galloway and Thacker 2007, 34). Curiously, although first published in 2007, Galloway and Thacker’s volume already anticipates what would later become a pandemic. In fact, their analysis is so anticipatory of the effects that we are now experiencing to the point of being almost indistinguishable. Specifically, when it comes to understanding SARS as a new virology of globalization and its associated transgression of boundaries (90):

The SARS virus, for instance, crosses the species boundaries when it jumps from animals to humans. It also crosses national boundaries in its travels between China, Canada, the United States, and Southeast Asia. It crosses economic boundaries, affecting the air travel industry, tourism, and entertainment industries, as well as providing initiative and new markets for pharmaceutical corporations. Finally, it crosses the nature–artifice boundary, in that it draws together viruses, organisms, computers, databases, and the development of vaccines. Its tactic is the flood, an age-old network antagonism. (91).

Largely derived from General Systems Theory, Galloway and Thacker’s amplification5 of the principles governing networks enables them to state that, when it comes to infectious diseases, they “take advantage of a range of networks, many of them human-made: biological networks of humans and animals, transportation networks, communications networks, media networks, and socio-cultural networks.” In this sense, “[m]edia and socio-cultural networks can work as much in favor of the virus as against it – witness the pervasive media hype that surrounds any public health news concerning emerging infectious diseases” (119). And the same could be said regarding computer viruses, especially considering the outburst of both artistic and non-artistic variants throughout the 1990’s and the beginning of the new millennium, specifically exploring public concern on the topic, by using alarming interfaces and/or payload simulators, but resulting in a not so alarming, close to innocuous, technical damage.6

Nonetheless, if, in 2006-2007, Galloway and Thacker’s understanding of the potentially nefarious effects of media and socio-cultural networks came in association with the fear of bioterrorism, in 2020-2021, amid a pandemic, it became linked to the so-called post-truth era, namely, populism and authoritarianism marked by waves of misinformation. As a network that congregates and, to some extent, paradoxically (im)materializes many other subnetworks – communications, information, socio(cultural) networks – the infectious possibilities of the Internet seem evident. What can happen, then, when “good viruses” take advantage of the networking abilities of its (g)host7 medium?

Art in Quarantine: a (post?) pandemic atlas

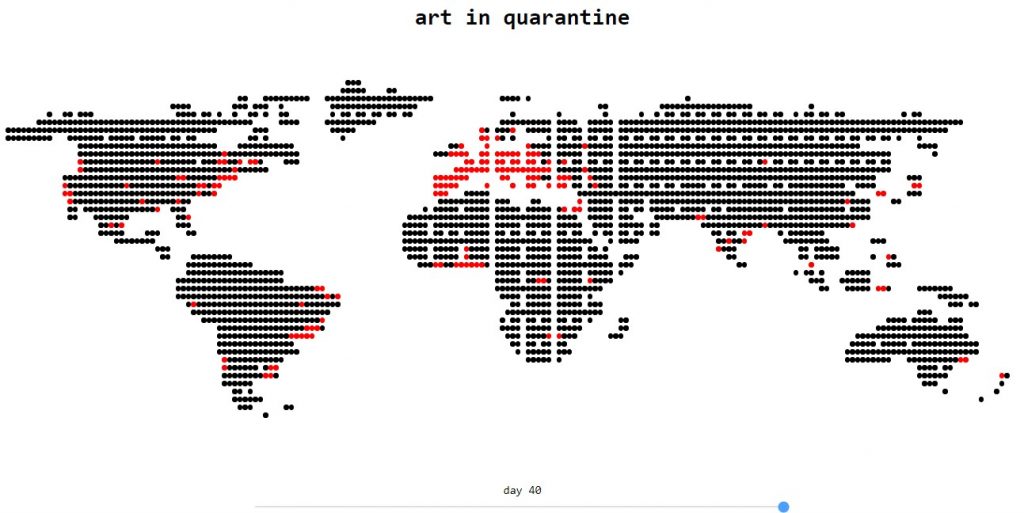

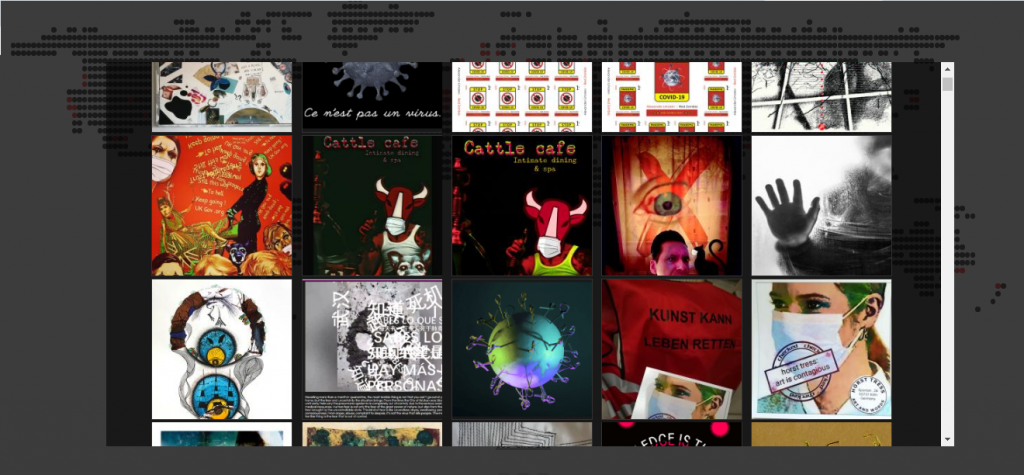

Reminiscent of a “good” viral-like behavior intrinsic to mail art culture and community(ies) working as subnetworks, the “Art in Quarantine” project (AiQ) is an online gallery currently hosting more than 900* artworks produced in the first 40 days after the Covid-19 pandemic status (March-April 2020) by 350 authors from 57 different countries and aimed to facilitate a safe place for artistic creation and exhibition. In adopting several principles of mail art culture to the digital sphere, namely collaborative practices as a form of disrupting conventional (art) channels, the AiQ project was launched after an international Open Call for (e-)mail art and art via email by Portuguese cyberliterature collective wr3ad1ng d1g1t5. Just like codework artists took advantage of network art mailing lists8, the collective made use of mail art channels in digital communication – a subnetwork that, to a large extent, currently relies on the Internet to keep its global snail mail circulation alive – as its main medium for (artistic) propagation.

Functioning as a net art-like installation, the AiQ platform includes an interactive digital map in which users can track the arrival of artworks by day and location. Symbolically subverting a logic of infection, contamination, and contagion (from the Latin contagionem, “a touching, contact”), this digital interface conveys and reveals, day after day, the transmission chain of artistic expression (or infection, as proposed by Malevich). Like computer viruses replicated by artists in the 1990’s, the emphasis is placed on the poetic/symbolic value ambitioned for the navigation experience, which is defined by the AiQ’s interface. Nevertheless, this strategy was also motivated by the necessity of providing an e/affective alternative to the standardized affordances and constraints of social media platforms used as exhibition venues.9 Rather than simply representing the curators’ choice of creating a distinct interaction experience for AiQ, the need for a ‘custom made’ interface was also related to the technical limitations presented by these types of platforms, namely regarding the typologies, formats, and possibilities of display allowed.10

This approach can be related to the concept of the metainterface, as proposed by Christian Ulrik Andersen and Søren Bro Pold, in their homonymous volume:

Although the interface may seem to evade perception, and become global (everywhere) and generalized (in everything), it still holds a textuality: there still is a metainterface to the displaced interface. Artistic practices may help us to see this by reflecting the fissures in the kinds of realities that the metainterface produces. That is, they may reflect their own production, and in this way, challenge the disappearance of the interface, and make it much less innocent than corporate rhetoric otherwise suggests: the ubiquity, pervasiveness, and real-time smoothness of the interface are loaded with worldviews, values, ideologies, politics, regulation, and conflicts, and thus also hold within them potential new forms of expressiveness. (Andersen and Pold 2018, 20)

Moreover, in alignment with Jill Walker Rettberg’s analysis of speculative interfaces as “a key attribute of electronic literature” – often serving as a way “to explore and test new possibilities in technical systems and platforms”, but also as possible “methodology in the digital humanities,” frequently used to “document aspects of our shared reality” – (Rettberg 2021, n.p.), the AiQ interface was intended to reflect its technological and cultural context(s) of production.

Overall, AiQ features artworks covering multiple formats and genres and presents two possible types of display: an individual gallery, containing the individual experiences of each of the participant authors, as well as a collective gallery featuring all the artworks, and presenting yet with another type of experience, that is, the possibility of identifying visual patterns from a global experience of confinement due to COVID-19.

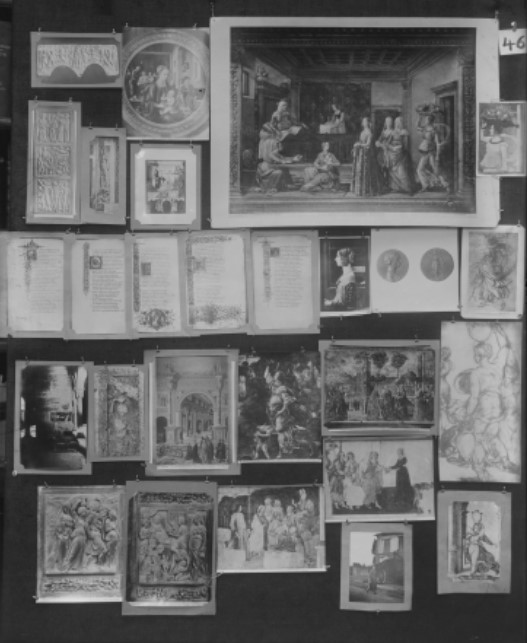

In this regard, a comparison can be made between AiQ collective gallery and Aby Warburg’s Atlas Mnemosyne project (1929). On its surviving, unfinished version, the Atlas consisted of a series of 63 panels, composed of more than 900* drawings, prints, newspaper clippings, and photographic reproductions of paintings, sculptures, and everyday objects. One of its particularities is the way in which Warburg applied the concept of “bewegtes Leben” (life in motion or animated life) to (artistic) images, exploring the idea of “Gebärdensprache” (the language of gesture) as an earlier type of “pathosformel” (pathos formula), composed by emotionally charged visual tropes that were transmitted, since the Antiquity, by Renaissance artists.11 By doing so, as Georges Didi-Huberman describes in The Surviving Image(originally published in French in 2002), Warburg experiments on the possibility of assembling an Atlas of archetypal forms pertaining to western (psycho-emotional) history. This possibility rises from an understanding of the ability of images to “call upon the act of looking, but also upon knowledge, memory, and desire, and upon their capacity, which is always available, of intensification,” involving “the subject in its totality — sensorial, psychological, and social” (Didi-Huberman 2017, 88-89).

Interestingly, as Didi-Huberman points out, Aby Warburg was profoundly influenced by the technological production of his time, namely the advances in chromatography, dynamography, and seismography. Regarding the latter, Warburg would in fact metaphorically compare the challenges “the historian must confront” to that of a seismograph, when trying to decode and translate the pathological shockwaves of historical events amongst their own, interior, experience of the event. And just as a seismic event affects the device itself, the historian would also empathetically tremble in response to the “symptoms of the age” (2017, 72) – a metaphor that is not far from the ways in which Malevich accounted for the transhistorical, material and materialist character of art (Groys 2016, n.p.). As for the Dynamogramm (along with the notion of Pathosformel), it already presupposes “an energetic and dynamic conception of the trace, which is viewed as a reflexive prolongation of the organic movements—mediated, however, by a stylus [style], a word that must be understood in its technical sense as well as in the aesthetic sense” (Didi-Huberman 2017, 71).

Following Warburg’s techno-iconographic and psychoanalytic approach, it is, therefore, possible to identify some of the themes or archetypes enunciated by the Atlas Mnemosyne in AiQ’s galleries, more precisely the tensions and dualities encapsulated in these pathos-charged representations of the pandemic experience. For instance, pathos formulas of sacrifice and triumph, order and chaos, anger and resignation, ecstasy and melancholy, and often abstraction (more or less exuberant or humoristic) as a response mechanism to fear – or to what Warburg would call loss of “the how of metaphor” (Hönes 2013, n.p.), whose definition is somewhat similar to a lack of recognizable explanations when facing an invisible and incomprehensible threat.12 But perhaps one of the most relevant aspects of AiQ is the way in which artistic representations are indeed permeated by digital media aesthetics and apparatus. Confirming the idea that digitality started mediating every single aspect of this pandemic, alongside the themes and topics previously listed, it is possible to identify corresponding digital(ized) visual and sound trope-like motifs: the contrast between inside and outside life, transparency and opacity, windows and screens, stillness and movement, noise and silence, greyness and vividness of colors, plus animistic and geometrical representations of the virus.

E-Lit: a collaborative (sub)network?

For the purposes of the paper that preceded this article, at ELO 2021 we presented a series of four selected artworks that, regardless of their fractal nature in the context of its host, the AiQ platform, were analysed as organisms that are part of a specific subnetwork, or population. While the selected artifacts, namely those falling under the category of new media art13, are not, stricto sensu, artworks created from the inside of e-lit community(ies), all can be categorized according to current definitions of electronic literature. For instance, the one provided by N. Katherine Hayles on the ELO’s website, in which Hayles highlights electronic literature’s hybrid nature, as “a ‘hopeful monster’ (as geneticists call adaptive mutations) […] created and performed within a context of networked and programmable media” and “informed by the powerhouses of contemporary culture, particularly computer games, films, animations, digital arts, graphic design, and electronic visual culture” (Hayles 2007). Accordingly, in their self-reflective nature, all four artworks act as distinctive virus strains that make distinct uses of different programming and poetic languages for artistic purposes: a mobile screen capture performance, a generative online memorial, a software system/digital art installation, and an elegiac e-poem.

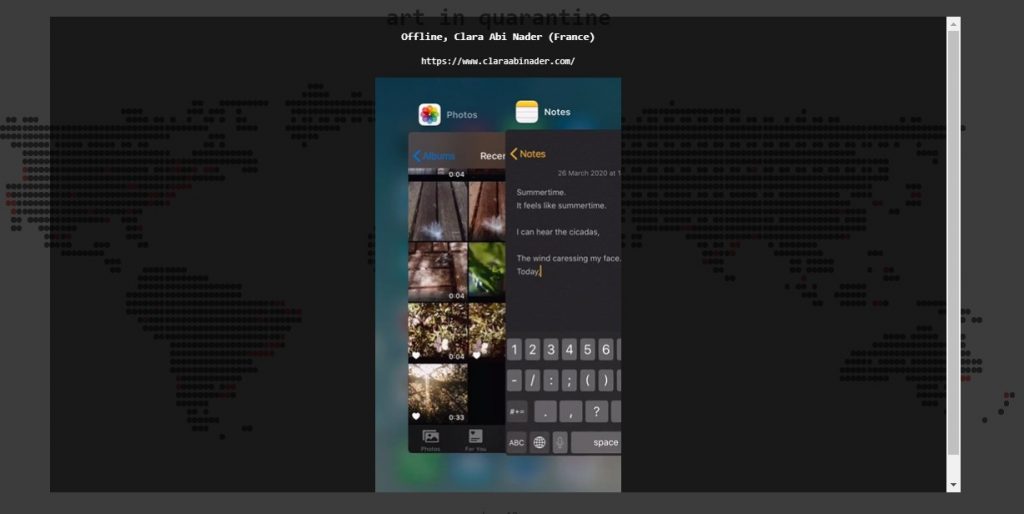

In Status Offline14, Lebanese visual artist and photographer based in Paris, Clara Abi Nader, makes use of screen captures and screen recordings of her mobile’s videos, photos, and text notes to produce a performance of an alternative daily life, while in confinement. Largely deprived of physical access to the outside world, the colourful videos and photographs stored in her mobile phone are used to (re)connect with nature, by revisiting a specific selection of summertime visual tropes. Using a layer of textual notes intended to express sensorial, emotional, and psychological experiences associated with her memories, the author creates a fictional narrative, an infectious literary constructo overlapping present reality indoors, and weaving meaning into the otherwise isolated videos and images portrayed.

During her performance, the device and its mediating action are always made visible, but a sense of proximity, even intimacy, prevails, whilst it is the medium that grants us access to the author’s feelings and thoughts animated through writing. Ironically, this piece ends with a disclaimer stating that “Clara isn’t online,” playing with the fictional nature of life inside and outside (digital) screens.

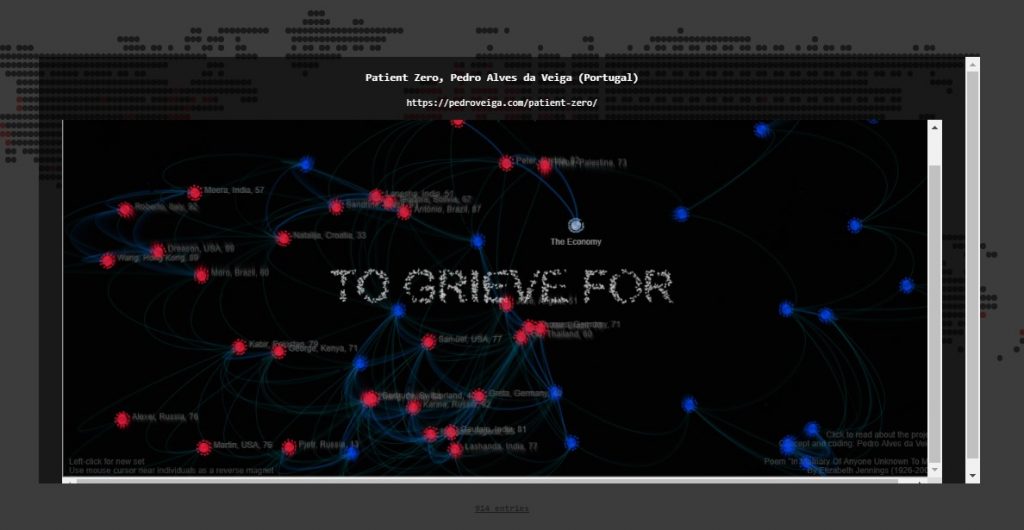

In our second example, Patient Zero (In Memory of Anyone Unknown to Me), by Portuguese digital artist, Pedro Alves da Veiga, an adaptation of Elizabeth Jennings´ poem “In Memory Of Anyone Unknown To Me” is used as part of an interactive online memorial of a different kind. Mimicking the action of a virus, the poem is hacked and transformed into text-dust animated sentences, conveying an additional, visual, layer of poetic meaning; “From ashes to ashes”. The poem is then placed in dialogue with a symbolic and interactive representation of the transmission chain of the Coronavirus, through which the author pays homage to COVID-19 victims worldwide.

The individuals are represented by bright blue particles, except for Patient Zero, a single, initially infected individual, represented in contrasting red. Their real name, age, and country of origin, generated from actual national databases, are (finally) made visible by the author, humanizing otherwise undifferentiated, anonymized particles. By interacting with the screen, the observer, whose cursor is presented as ‘The Economy’, accelerates the contact between infected individuals, spreading the disease and increasing the death toll. The interaction is accompanied by a soundtrack comprising a slowed-down speech by Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, in March 2020, famously comparing Coronavirus to a mild flu and condemning lockdown strategies adopted in other countries.

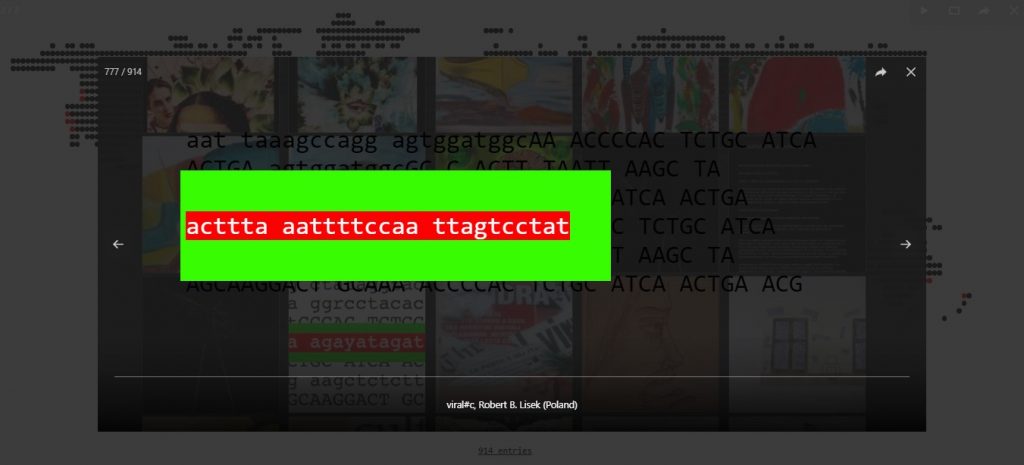

Presenting a distinct form of digital infection, the third example, viral#c, by polish artist, mathematician, and composer Robert B. Lisek, is a rendering of the software program developed in the context of a larger project which previously resulted in a video and sound installation. The program allows for the combination of the author’s DNA sequence with that of different viruses (Lloviu virus, Poliovirus, Marburg virus, HIV, and Ebola virus), which gradually transform the initial sequence, generating new, entwined, sequences. The newly generated sequences are then converted, in real-time, into pointing colour and sound outcomes and retroactively fed back into the machine.

By exposing the _wordlyphagic processes present in the interaction of the author’s genetic code with that of viruses and other pathological human and nonhuman agents – the software program that acts both as a mediator and an active co-author – ultimately, in its AiQ rendering, viral#c reveals that language is indeed a virus and that viruses are language, in whatever form they may take. Resonating Burroughs understanding of language in its material dimensions and infectious ability to generate and transmit meaning, in viral#c, language acts both as a medium and a sign of its own; i.e., acting like other cultural/technological artefacts/mediators, by assuming a symbiotic behaviour regarding their (non)human host.15

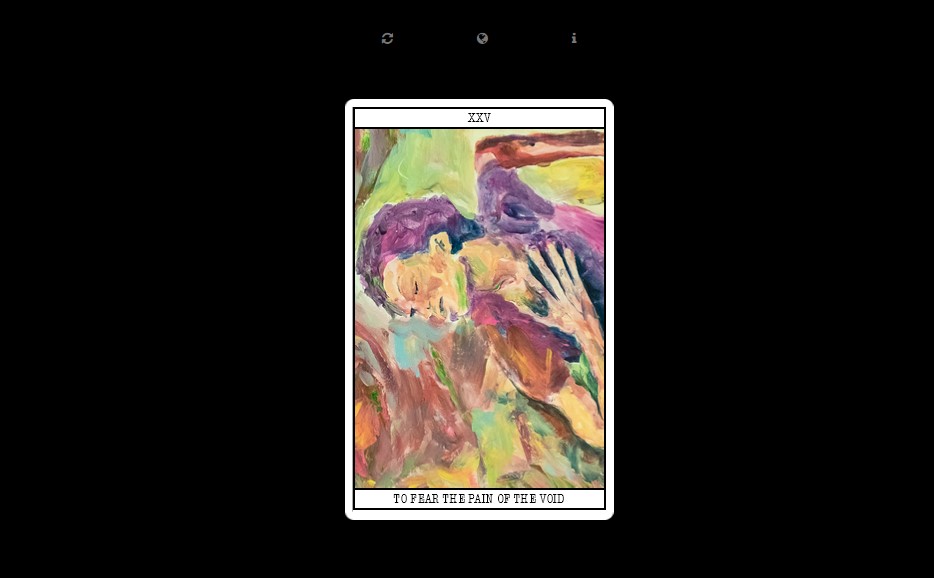

The final example presents another type of collaboration, one between two members of cyberliterary artist collective wr3ad1ng d1g1t5 (Diogo Marques and João Santa Cruz) and Portuguese painter Daniela Reis. Drawing similarities with Clara Abi Nader’s Status Offline, in RE\VERSE: an elegiac e-poem, text and image (plus sound) work together in creating a narrative around the experience of confinement. However, in this case, the mobile screen is replaced by a flipping tarot-like card reading a specific combination of text and image at each interaction, namely 40 alternate details from the “Sanity Diaries” series, by Daniela Reis, and 40 different verses from Diogo Marques’ “Quarantine Poem”.

The apparently subtle variation in iterations emulates the feeling of repetitiveness that has marked the authors’ own experience of quarantine, whilst in isolation at home (in Daniela’s case, away from the atelier). Nevertheless, the sound of footsteps in the background, while reinforcing repetitiveness, also invites us to move forward in/with this (nonlinear and open-ended) journey through several days of uncertainty and fear. In a similar way, amongst blurry and contrasting glimpses of movement, thoughts, and feelings, the softness of the background music, playing in a crescendo and highlighting the dreamlike quality of the paintings, comforts us and even might inspire us to continue.

On a final note, RE\VERSE presents itself as a product of a digital, networked, (trans)mutation process, combining various results (and collaborations) born out of constraint. Starting as a combinatorial ‘Quarantine Poem’ around a series of paintings, RE\VERSE was first presented as part of the AiQ networked archive, in March 2020. After a (digital) process of poetic and aesthetic transformation, it was then presented in its current instantiation, an interactive e-poem, as part of COVID E-LIT online exhibition, in the context of ELO 2021 Conference and Festival (May 2021).

Much like AiQ, although in a specific context and focusing on Electronic Literature’s community(ies), COVID E-LIT provided a platform16 for exhibiting “pandemic digital art and e-literature”, addressing the pandemic crisis, as well as “the wider crises of our contemporaneity” (Nacher et al. 2021, n.p.). Interestingly, in a preparatory round table organized one year prior to the exhibition, titled “E-lit Pandemics”, the curators - Anna Nacher, Søren Pold, and Scott Rettberg - discussed works “such as poetry and narrative generators, collective narratives, and interactive fiction” that were already dealing “contextually and thematically with the virus, social distancing and isolation […] and the absurdities of everyday life as we adjust to an online social sphere” (Nacher et al 2020, n.p.), hence resonating with some of the topics, or patterns, identified in the AiQ artworks. Furthermore, Nacher, Pold, and Rettberg highlighted the opportunity presented, not only to “signal the emergence of new e-lit related practices emerging during the COVID era”, but also to promote “new ways of understanding online media” through electronic literature and net art (2020, n.p.).

This opportunity became particularly evidenced through the “massive shift of transferring almost every aspect of our everyday life online”, resulting “both in an explosion of new forms of creativity and the acute syndrome of much-touted ‘Zoom fatigue’” (Nacher et al. 2021, n.p.), a topic explored by some of the works featured in the COVID E-LIT exhibition, namely Alex Saum’s #Room3. In this (meta)performative parody, the author makes use of digital tools, such as videoconferencing software that has become widespread and almost prosthetic to many people’s ‘new normal’ daily lives, one year long into current pandemic times.

In this sense, (post)digital online platforms such as AiQ and COVID E-LIT confirm the relevance of digital media for the (artistic) understanding of this cultural, social, psychological, and emotional moment in the history of humankind, performing a symbiotic exchange and empathetically trembling with the authors’ own everyday pandemic experience. In addition, either resulting from a process of “online collective creativity” (Nacher et al 2020, n.p.) and/or functioning as (g)hosts to foster artistic creation, it is our belief that both platforms illustrate the potential of the Internet to promote the expansion of collaborative (sub)networks. Being representative of an optimal ecosystem for the development of benign artistic viral-like behaviour (pharmakon!17), they take advantage of the Internet’s rhizomatic and virulent ability for propagation of infections and mutations – ultimately materializing (even, perhaps, amplifying) some of the Coronavirus’ own characteristics; an immaterial, airborne virus, made visible only through its tropes (or masks) and symptoms.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the AiQ authors, most particularly those whose artworks were featured in this article. We would also like to thank the editors and reviewers of EBR, for their support, thoughtful advice, relevant comments, and suggestions. Parts of this article were presented at SLSAeu2021 and ELO2021.

Ana Gago’s research conducted for this article was supported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT), through a Ph.D. fellow grant (ref.: SFRH/BD/148865/2019), as part of a Ph.D. project at the Catholic University of Portugal, School of Arts.”

Works cited

Amerika, Mark. 1993. Avant-Pop Manifesto. Last accessed 14 December 2021.

Andersen, Christian U., & Pold, Søren B. 2018. The metainterface: The art of platforms, cities, and clouds. MIT Press.

Burroughs, William S. 2011. The Ticket that Exploded. New York: Grove Press.

Burroughs, William S. 2005. The electronic revolution. Ubu Classic.

Didi-Huberman, Georges. 2017. The Surviving Image. Phantoms of Time and Time of Phantoms. Trans. Harvey L. Mendelsohn. The Pennsylvania State University Press.

Galloway, Alexander R., and Eugene Thacker. 2007. The exploit: A theory of networks, Vol. 21. University of Minnesota Press.

Groys, Boris. 2016. In the Flow, Verso.

Hayles, Katherine N. 2007. Electronic Literature: what is it?. The Electronic Literature Organization. https://eliterature.org/pad/elp.html#sec1

Hönes, Hans Christian. 2013.“Panel 45 – Introduction”. In Mnemosyne: Meanderings through Aby Warburg’s Atlas. https://warburg.library.cornell.edu/image-group/panel-45-introduction.

Knight, Kim. 2015. “Sublime Latency and Viral Premediation.” In Electronic Book Review. http://electronicbookreview.com/essay/sublime-latency-and-viral-premediation/

Marques, Diogo. 2022. “‘Grasp All, Lose All’: Raising Awareness Through Loss of Grasp in Seemingly Functional Interfaces”. In Open Library of Humanities 8(1). DOI: https://doi.org/10.16995/olh.6393

Mietzsch, M., & Agbandje-McKenna, M. 2017. “The good that viruses do”. In Annual review of virology, Vol. 4, iii-v.

Mitchell-Boyask, Robin. 2007. Plague and the Athenian imagination: Drama, history, and the cult of Asclepius. Cambridge University Press.

Nacher, Anna, Søren Pold and Scott Rettberg. 2020. “E-lit Pandemics - Roundtable”. https://elmcip.net/critical-writing/e-lit-pandemics-roundtable

Nacher, Anna, Søren Pold and Scott Rettberg. 2021. “COVID E-LIT: Digital Art from the Pandemic curatorial statement”. In Electronic Book Review. https://doi.org/10.7273/kehh-8c36

Newman, Jane O. & Hatch, Laura. 2013. “Panel 70 – Introduction. The Baroque as the Renaissance?”. In Mnemosyne: Meanderings through Aby Warburg’s Atlas. https://warburg.library.cornell.edu/image-group/panel-70-introduction-1-5

Parikka, Jussi. 2016. Digital contagions: A media archaeology of computer viruses. Second Edition. Peter Lang.

Rettberg, Jill. 2021. “Speculative Interfaces: How Electronic Literature Uses the Interface to Make Us Think about Technology”. In Electronic Book Review. https://electronicbookreview.com/essay/speculative-interfaces-how-electronic-literature-uses-the-interface-to-make-us-think-about-technology/

Thacker, Eugene. 2004. Biomedia. Vol. 11. University of Minnesota Press.

Thucydides. 1956. History of the Peloponnesian War. Trans. Charles Forster Smith. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. https://ryanfb.github.io/loebolus-data/L108.pdf

Footnotes

-

The word used by Thucydides is anomía (ἀνομία, -ας, ‘absence of law, rule, order or legality’: ἀ-, ‘deprivation, negation’; νόμος, ‘law, rule’), in a description that seems to place phýsis above nómos, the laws of nature, for example, hedonistic pleasure, above other types of laws or conventions (1956, 354-5). ↩

-

“The word is now a virus. The flu virus may once have been a healthy lung cell. It is now a parasitic organism that invades and damages the lungs. The word may once have been a healthy neural cell. It is now a parasitic organism that invades and damages the central nervous system. Modern man has lost the option of silence. Try halting your sub-vocal speech. Try to achieve even ten seconds of inner silence. You will encounter a resisting organism that forces you to talk. That organism is the word. In the beginning was the word” (Burroughs 2011, 49). ↩

-

In biology, “a measure of the attraction of one biological molecule toward another molecule, either to modify it, destroy it, or form a compound with it.” Examples of this being “enzymes and their substrates, or antibodies and their antigens.” https://www.genscript.com/molecular-biology-glossary/8371/affinity ↩

-

See also: https://elmcip.net/critical-writing/universal-viral-machine-bits-parasites-and-media-ecology-network-culture ↩

-

In medical scientific terminology, amplification refers to a process considered responsible for the formation of new genes, as well as for the appearance of mutations that may or may not be favorable to evolution, and therefore, playing an important role in heavy words like cancer, i.e., when a tumor cell copies DNA segments. In doing a selective copying of a gene or any sequence of DNA, amplification occurs in the body with the purpose of fulfilling the need of cells for proteins. ↩

-

See for instance Biennale.py (2001), a computer virus created by artist collective 0100101110101101.org and hackers group Epidemic, for the 49th Venice Biennale: https://0100101110101101.org/biennale-py/ ↩

-

Reference to Marcel Duchamp’s famous portmanteau: “A Guest + A Host = A Ghost”, printed and distributed during the opening of William Copley’s show at Galerie Nina Dausset, Paris, 1953. http://archives.carre.pagesperso-orange.fr/Duchamp%20Marcel.html ↩

-

In “Codeworks: Netart on the border of Language and Codes” (2005), Florian Cramer relates the development of a specific type of “codeworks” a term coined by theorist and artist Alan Sondheim which consists of “e-mails whose text, however, calls to mind associations of computer crashes and interferences, viruses and spam”, with the disruptive use of “network art mailing lists”: https://elmcip.net/creative-work/codeworks-netart-border-language-and-codes ↩

-

Note due to artistic/literary projects focusing on the creative and metarreflexive abilities and applications of social media, both online and offline. On this regard, see María Goicoechea ‘s analysis “The Art Object in a Post-Digital World: Some Artistic Tendencies in the Use of Instagram”, presented at the ELO 2021- Conference and Festival: https://electronicbookreview.com/essay/the-art-object-in-a-post-digital-world-some-artistic-tendencies-in-the-use-of-instagram/ ↩

-

There were several COVID themed exhibition projects using social media platforms in the very first months after the declaration of the pandemic status by the WHO, some with a considerable impact at the international level, such as “The COVID Art Museum” on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/covidartmuseum/ ↩

-

Focusing on the Renaissance period but drawing patterns of a visual continuity from Ancient Greece to the Republic of Weimar, this fractal-like montagedisplayed Warburg’s attempt of representing two, often duelling, types of responses to psychological and emotional events. As described in the draft “Introduction” (“Einleitung”) to the Atlas, the first being a Dionysian, reactive and “phobic-kinetic”, and the second an Apollonian, more reflective and “artistically” contained type of response (Newman and Hatch 2013, n.p.)https://warburg.library.cornell.edu/image-group/panel-70-introduction-1-5 ↩

-

https://warburg.library.cornell.edu/image-group/panel-45-introduction ↩

-

We are following Oliver Grau’s definition of new media art, “a comprehensive term that encompasses art forms that are either produced, modified, and transmitted by means of new media/digital technologies or, in a broader sense, make use of ‘new’ and emerging technologies that originate from a scientific, military, or industrial context,” as described in: https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199920105/obo-9780199920105-0082.xml ↩

-

Part of short-video series, “Thoughts on Screen”.https://www.claraabinader.com/thoughts-on-screen ↩

-

See also Milton Laufer’s “Word is a virus.” http://www.miltonlaufer.com.ar/conwaysgame/ ↩

-

COVID E-LIT’s main interface was designed and implemented by e-lit artist Jason Nelson, thus demonstrating another type of metainterface. Moreover, all exhibitions are interconnected with each other, offering the visitors the possibility of navigating between several rooms. https://www.eliterature.org/elo2021/covid/ ↩

-

See Rui Torres and Eugenio Tisselli’s take on the Stieglerian idea of “technology as pharmakon”. https://electronicbookreview.com/essay/in-defense-of-the-difficult/ ↩

Cite this article

Marques, Diogo and Ana Gago. "Language |H|as a Virus: cyberliterary inf(l)ections in pandemic times" Electronic Book Review, 6 March 2022, https://doi.org/10.7273/jhrr-0218