Learning Management Platforms: Notes on Teaching “Taroko Gorge” in a Pandemic

Dani Spinosa reflects on the relocation of e-Lit scholarship and pedagogy "in the remote classroom for the precariat writ large."

When I first proposed this paper, I had wanted this to be a closer analysis of learning management systems and their abilities and shortcomings in encouraging non-programming students to engage with code in critical and literary ways. But, as it so often does at the end of term, the grading took its toll. Indeed, this is particularly true for me as an adjunct instructor juggling the grading for more students than I care to admit while preparing for the next term to begin. So, this paper is in some ways less of an analysis of the platforms at play, and more of an analysis of their incongruity, and what that incongruity says about the role of electronic literary study in the remote classroom for the precariat writ large. Indeed, we might argue that as an adjunct instructor during the pandemic, I am in a rather unique position to speak to the use of the learning management system, or LMS, as a pedagogical platform. I currently teach at three different post-secondary institutions—York University, Trent University, and Sheridan College, all in southern Ontario, Canada—and I am currently teaching using three different LMSs (Blackboard, eClass [Moodle], and SLATE [Brightspace]). This pandemic has clearly laid bare several of the difficulties of precarious labour in the academy, and the need to fluently navigate several disparate platforms is just one. I would like to use this unique position to begin to speak to the role of pedagogies of digital literature to help students develop critical digital literacies, and how the proprietary LMS might influence or impede that process.

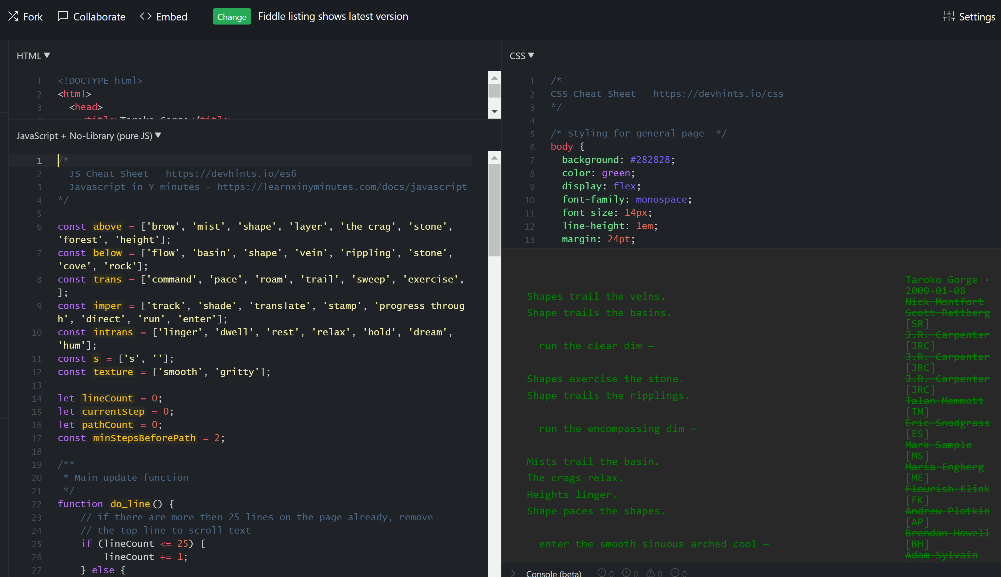

What follows is an equal parts scholarly and reflective pedagogical analysis and critique of the use of the LMS Blackboard for course delivery of ENGL4309 Digital Adventures in English: Engaging with the Digital Humanities at Trent University in Peterborough, Ontario. ENGL4309 is a fourth-year seminar that is marketed primarily as a course in digital humanities tools for the study of literature and the digital literary. As far as I understand it, this was the first year that Trent was able to mount such a course. Incidentally, they found themselves without a a digital humanities professor available to direct the course at the time of its offering and brought me on as contract faculty to prepare and direct the course. One of the DH tools that I used as a part of a module on digital literatures is Nick Montfort’s “Taroko Gorge” and the many remixes thereof. By situating this classic work of electronic literature in this way, my goal was to treat the programming language of “Taroko Gorge” and the popularity of its remixes as a DH tool, and to thus follow in the excellent arguments made recently about electronic literature as digital poetics.

These arguments are compiled exhaustively in Dene Grigar and James O’Sullivan’s recent volume, Electronic Literature as Digital (2021). In the introduction to this collection, Grigar argues persuasively that “electronic literature is the logical object of study for digital humanities scholars who have, by the second decade of the twenty-first century, cut their teeth on video games, interactive media, mobile technology, and social media networks; are shaped by politics of identity and culture; and able to recognize the value of storytelling and poetics in any medium” (3). Indeed, as Scott Rettberg has argued, “both ‘electronic literature’ and ‘digital humanities’ are loosely defined not by their attachment to a historical period or genre but by a general exploratory engagement with the contemporary technological apparatus” (127). So, as a part of one of the electronic literature modules for this course, I asked my students to remix “Taroko Gorge,” as we did when I first encountered the work through the Digital Humanities Summer Institute (DHSI) several years before through Dene Grigar and others. And, indeed, as one reviewer of the proposal for this paper remarked, “The ‘Taroko Gorge’ remix assignment is an enduring piece of e-literary pedagogy for good reason.” I wanted to position the reading, adjusting, and remixing of the code of “Taroko Gorge” as a tool of digital humanities scholarship, to take for granted the fact that an ability to recognize and read code is a cornerstone of both digital humanities and electronic literature.

However, extending this classic electronic literature activity to upper-year students who were, prior to that point, completely unfamiliar with the field of electronic literature, and most of whom had never interacted with code before at all, proved to be difficult. I am sure I am preaching to the choir here, but it bears mentioning that the diversity of access tools (software and hardware) that students use to engage in their online courses make the already difficult task of encouraging liberal arts students, most of whom know basically nothing about programming, and some of whom have difficulties using technology more generally, to mess with the JavaScript and the CSS of “Taroko Gorge”’s remixable code. I was expecting these difficulties. But what I was not quite expecting—or not expecting in this way—were the difficulties of trying to use the required LMS to share material. That is, in training for pandemic remote teaching, I was informed of Trent’s request—as a relatively small institution—that instructors use the proprietary software Yuja to record and share all lecture materials on the Blackboard LMS and to use Leganto to share all possible readings through the library. In other words, Trent wanted to make sure, where possible, that instructors were using the internal proprietary software to save on server space, to streamline work for IT, and to standardize pedagogical practices across the disciplines. These were requests that I, as a first-time contract instructor at the university, was worried about circumventing for fear of jeopardizing future offers from the department.

One of the most important difficulties of this assignment, indicating barriers to access for student and instructor alike, was attempting this project using the proprietary software of the LMS, including unique platform dependencies and an inability to have students collaboratively or separately work on and test the code within the LMS itself. There was also, of course, the problem of trying to share parts of the code in the forums which would not properly display because of translation issues with the LMS platform. I was getting frustrated and running out of time, and the students were starting to feel more instead of less alienated by the coding activity.

Essentially, the job of incorporating electronic literature when teaching using a learning management system involves a little of what Davin Heckman calls a “a patient strategy” (277) in his contribution to the aforementioned Grigar and O’Sullivan volume. In this essay, appropriately titled “Learning as You Go: Inventing Pedagogies for Electronic Literature,” Heckman urges burgeoning electronic literature professors to work compiling research that speaks to the specific institutional context that one operates in, seeking areas in which electronic works complement or complicate existing curricula in a meaningful way, and work diligently to create places in the curriculum that can include electronic literature as a standalone subject or part of a dynamic portfolio of rhetorical, computational, and/or aesthetic practices that make sense within a broader educational setting (277).

The call is persuasive and, I would argue, important towards fostering critical digital literacies in our classrooms. But, as Heckman nods to the extra work involved in creating spaces—literal, virtual, and metaphorical—for pedagogies of electronic literature, I cannot help but wonder how the lack of access, influence, and time of the adjunct professor affects the ability to incorporate digital literatures into existing syllabi, and to insist on e-literary study within our departments.

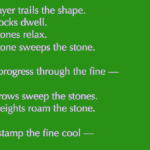

Being an adjunct instructor requires a lot of “Learning as You Go,” and a number or workarounds. And ultimately, unable to distribute and collaboratively work on our “Taroko Gorge” remixes using the LMS platform, I eventually had to move outside of the platform with which my students had finally become comfortable. What I ended up doing, with the help of a programmer friend of mine Jon Orsi, was to share the editable code using JSFiddle, a “free code-sharing tool that allows you to edit, share, execute and debug Web code within a browser.” Marketed as a “Code Playground,” JSFiddle allowed Orsi to input Montfort’s code into the JSFiddle browser, separating the JavaScript and the CSS stylesheet, and allowing for an in-browser run of the code to see edits in real-time and to check for bugs.

The workaround worked, and students were able to take the edited code, “fork” it, and start editing on their own. Most still found the experience to be frightening, but those that spent the time—and watched the Yuja © recorded Zoom © call between Orsi and me designed to ease them into the process—ended up producing remixes and feeling accomplished and a bit more agential in the digital realm. I considered the overall activity to be a success. But, upon reflection for this paper, I was struck most by the stark contrast, in interface, appearance, and implied audience, between the open-access JSFiddle I used as a workaround, and the proprietary industry-standard LMS that we used for the rest of the course. JSFiddle is dark and minimalist (see Figure 1), reminiscent of a ‘90s cyberpunk hacker film. It is clearly a place where programmers can adjust—and can even collaborate—on the code before moving it to the project itself, a necessarily temporary, liminal space, and one that is well-suited for the temporariness of the coding used by students remixing “Taroko Gorge.” On the contrary, Blackboard bears all the markers of a sleek, designed, and clearly proprietary LMS (see Figure 2). I am not blowing anyone’s mind to make such an observation. The two platforms differ radically in funding, size, and intended use. But the incongruity of the two platforms—and how much their appearance demonstrates this—brought to the fore the question of how and where students have become familiar with technology, and how alienated students from outside of technological disciplines are with code, with programming language, with the back end at all.

Of course, one of the primary learning objectives of an assignment like the “Taroko Gorge” remix is building the critical digital literacy of recognizing that all digital texts are two texts: a code, and its reconstitution. I remember distinctly and fondly the empowerment I felt when I was able to adjust the JavaScript on my own the first time. Following Serge Bouchardon’s arguments in his “Mind the Gap! 10 Gaps for Digital Literature,” this assignment is designed to at least in part reveal the basic mechanisms of how code shapes the digital text to readers who do not know how to program, as was the case for every student who took this course with me. And, though I am learning slowly but surely how to program on my “spare time”—an inside joke for any other adjunct instructors—I am not a programmer, and I am not a computer science instructor. What I mean to say here is that an assignment like this works to begin to close “the gap separating us from digital literacy” that Bouchardon observes. But the incongruity of the LMS and the remixing project reveal a potential limitation that we need to be cognizant of as instructors of the digital literary and beyond. Part of the work of the pedagogy of electronic literature is to work to dismantle the cleanliness of the proprietary platforms we are asked to, or have no choice but to, use in our courses. More often than not, these platforms present networked technology as always already corporatized, complete, and impenetrable. And it is part of our job to break that down and to thus empower our students to learn, in small but meaningful ways, to penetrate beyond that exterior and thus to resist the role of platform in the corporatization of the university.

Works Cited

Bouchardon, Serge. “Mind the gap! 10 gaps for Digital Literature?” Electronic Book Review, 5 May 2019, http://electronicbookreview.com/essay/mind-the-gap-10-gaps-for-digital-literature/

Grigar, Dene. “Electronic Literature as Digital Humanities: An Introduction.” Electronic Literature as Digital Humanities: Contexts, Forms, & Practices, eds. Dene Grigar & James O’Sullivan, Bloomsbury, 2021, pp. 1-5.

Heckman, Davin. “Learning as You Go: Inventing Pedagogies for Electronic Literature.” Electronic Literature as Digital Humanities: Contexts, Forms, & Practices, eds. Dene Grigar & James O’Sullivan, Bloomsbury, 2021, pp. 275-86.

Rettberg, Scott. “Electronic Literature as Digital Humanities.” A New Companion to Digital Humanities, eds. Susan Schreibman, Ray Siemens, and John Unsworth, Wiley Blackwell, 2016, pp. 127-36.

Cite this article

Spinosa, Dani. "Learning Management Platforms: Notes on Teaching “Taroko Gorge” in a Pandemic" Electronic Book Review, 6 March 2022, https://doi.org/10.7273/ygq2-7k82