Platform In[ter]ventions: an Interview with Ben Grosser

In a series of interviews led in February and March 2021, Nacher, Pold and Rettberg examined how contemporary digital art and electronic literature responded to the pandemic. Their project on COVID and electronic literature was funded by DARIAH-EU and resulted in the exhibition prepared for the ELO 2021 Conference & Festival and the documentary film that premiered in June 2021 at the Oslo Poesiefilm Festival. Ben Grosser is one of the creators of 13 works that were interviewed for the project. He generously shares his thoughts on life and creative practice during the pandemic, the impact of platforms on the digital culture and creativity and platform culture in general.

Søren Pold

The first question is about your work in the exhibition. Can you describe it and also say what inspired you to produce it?

Ben Grosser

Sure, so the work is titled The Endless Doomscroller. It’s a website that presents an endless stream of abstracted, generalized bad news headlines in a format that will feel familiar to a lot of people. It’s a simplified social media feed kind of interface where it’s just a headline in a box and another headline in a box and a headline in a box, etc. And you can scroll as long or as fast as you care to, but you will never get to the end. It just literally will keep feeding these bad news headlines to you, forever.

The inspiration for this comes out of the early days of the pandemic and thinking about, well, my own experience of that time. But I think a lot of people had this experience and maybe to some degree still do, of especially, thinking in April 2020 for example, when I would be laying in bed late at night on my phone reading Reddit, the coronavirus subreddit, or looking at The Washington Post or The New York Times or just looking up news sources, kind of almost being stuck in a pattern of continually scrolling and scanning, looking for, I guess, good news in the midst of all the bad, perhaps. And by about June or so, a term started to come into popular usage, which is doomscrolling. And it turns out that term had been around for a while, but maybe wasn’t very well known. And then it started getting tossed around to describe this condition, because not only would I be looking to read the news, but I’d almost find myself feeling stuck reading the news. And I would do it late at night when I wanted to be sleeping, and then I’d wake up early in the morning and pick up my phone right in the bed and go right back to reading this news. Certainly the realities of the pandemic necessitated back then and still does, a degree of vigilance about new information. Is there anything new I need to know? But from my perspective, as someone who’s focused on the cultural effects of software, it’s not just the news that matters here, it’s the fact that it’s being delivered by interfaces that are designed to keep us engaged. And nothing was keeping us more engaged in April 2020, in May or June of 2020 than bad news about the pandemic. It’s what was attracting our attention. So it made me think about, what are the interface design aspects that are behind why I’m feeling stuck in the scroll, and who benefits from this relationship?

Søren Pold

That leads perfectly to the next question. We have experienced that artists are trying to process and make sense of the pandemic situation through their work. It is this catastrophe that you can’t really see or you know, well, sometimes you see it or you see it as the empty streets or as a lack of common normality. So the question is really what’s your artistic, literary or intellectual strategy for dealing with the pandemic. How do you try to make sense of it?

Ben Grosser

So, I feel like I’ve done it in ways that are fun and interesting to talk about in an interview and then ways that maybe aren’t, ways that a lot of us do of just eating lots of crackers and vegging out in front of the TV, Netflix and whatever, right? So I just want to acknowledge, like, I can list off projects that are relevant to that question, but it’s not like I have made great, wonderful, efficient use of my pandemic time. But certainly projects have been a way of navigating this for me. And so the Doomscroller was the first project I think I put out. Actually, no, the first project I put out in the pandemic was a work at the URL amialive.today. And it’s the simplest website. You go to that website and it gives you an answer and I’ll leave that to those who read the interview to try it out. But, it was just like dealing, like using my artistic kind of interest as a way of navigating the anxieties and also the kind of existential questions around it.

Another project that’s still ongoing is a series of visualizations of the scale of Covid death in the United States. This started in June or July 2020. I was thinking about how, especially in the early but also until recent days of the pandemic under the Trump administration in the United States, we had a leader who spent most of the time denying the severity or even the existence of a problem as the deaths mounted. And so I started making a visualization that would look at the area that was committed to a memorial for the 9/11 attack in New York City, which is a footprint of the former World Trade Center in lower Manhattan.

I started making a series of visualizations. I put them out once every month or two months or so, where I would take that footprint, which commemorated about 3,000 deaths in the United States, and I would start stamping it on top of lower Manhattan to see, well, what if we took the number of deaths that we’ve seen in the in the United States for the Covid pandemic and were to build memorials at that same kind of death to area ratio that we used for the World Trade Center. And at this point we’re over 500,000 deaths in the United States in terms of the official count, and the visualization basically now takes up the entirety of lower Manhattan from the village to Battery Park, from all the way to the east, all the way to the west. So that’s a series of visualizations I’ve put out.

I’ve also thought and have been continuing to think about feeds, and especially given that we had the pandemic intersect with the election in the United States—the presidential election in November—thinking a lot about disinformation campaigns and how those have been playing out. And that led me to create a work for TikTok, which is kind of the biggest craze here in terms of the App Store. It’s called Not For You. It’s what I call an automated confusion system. It’s essentially an automated browser for TikTok that will click on things and like things and follow hashtags and follow people, all without your input, as a way of trying to break out of the filter bubbles that are produced with its signature feature, which is an AI-driven feed called the For You page. So I think that’s, I don’t know if that’s where you were going with that question of how I navigate through projects, but that’s some of the projects I’m doing.

Søren Pold

Yeah, I think it’s interesting when you talk about 9/11 and the building of the monument to 9/11, because one of the things we also discussed is why there aren’t monuments to the Spanish Flu, for instance, which also killed a lot of people, like a hundred years ago, right?

Scott Rettberg

I read an article where somebody at The New York Times did research on this and found that there was like one bench in one park with a plaque on it (laughs).

Ben Grosser

Yeah, I mean, I think there’s some ways in which the scale of the death was so grand, has been so grand, not just the United States, of course, although I think we may be the most or are certainly high on the list in terms of per capita, but I think there’s been a difficulty in contending with that scale. So that’s one of the reasons I wanted to try to visualize it. There’s a tendency to say well, the numbers are just going up. They’re just getting bigger. When they were like at 3,000 it was kind of crazy. At 5,000 it was crazy. But once it’s say, the difference between 100,000, 110,000, maybe it doesn’t feel so big to people. It’s three 9/11s for a 10,000 bump. So that’s why I was thinking about it that way.

Søren Pold

Continuing this, can you say something about the genre or type of project that you were drawn to create during the pandemic? And why do you use these specific genres or types of artistic strategy?

Ben Grosser

Yeah, I mean, I think that the general genre would probably be net art. But it certainly, I think, breaks into other areas, too, potentially. For me, even more so in the pandemic than before, and even before the pandemic, I felt the same way. So it’s not like this is a new way of looking at the world. But so much of our experience of the world, our experiences of each other, are experiences of interaction with information and media. Our experiences of checking our bank account, and like everything else, has now been inscribed into software in some way or another. Software is the media through which we communicate, through which we access information. And so for me, software is the thing that I focus on. And net art in particular, making works that intervene in software systems or making works in this case, which I think of as trying to take existing software systems we’re all engaged with and simplifying them down to their most basic core fundamentals as a way of thinking about what it is we’re doing when we’re interacting with these platforms and systems. For me this is a great way, as an artist, to investigate the small bits of our daily life in technology. So, often what occurs to me is to build a website or a browser extension, or sometimes a piece of media, video or audio, that also draws from this world that we live in. But in the pandemic, this has escalated dramatically. I mean, now we’re used to all these little boxes as the feature of regular daily life, right? But that wasn’t so much the case a year ago. So it’s like we’re now really stuck in software, is how I think about it.

Søren Pold

Well, also, thinking about the Doomscroller, the aspect of software is important. But if you combine this with, say, the rhetorics of the constant doom, and also questioning where all these voices come from: Who’s saying this? Why am I told this? If you look at it as literature, what kind of narrator is this? Why am I being positioned as an implied reader, and what kind of reader does it make me into?

Ben Grosser

Absolutely. I mean, I’m really with you there. I think, for me, I talk about software, but the truth is that the other half of the equation are all of the bits of text that have been written that I’m drawing from as material for this project, for the Doomscroller project, and I mean, it’s not an unknown kind of thing that headlines are written to grab attention. They’re usually written by a major media publication written by editors, not by the authors of the article. They have different considerations. The New York Times does AB testing on its headlines to see which ones grab more attention. But certainly I think this moment of social media and its algorithmic feeds is kind of, what I would call a perfect but evil marriage between users stuck online, the platforms, and those who are writing these headlines. And, you know, the objective of social media feeds is not to inform. Facebook isn’t designed to inform us. It’s designed to engage us and it’s designed to produce engagement from us. A happy headline or even a neutral headline, of ‘things are looking OK’ or ‘we’re not sure how things are going,’ doesn’t necessarily grab the same attention as ‘everything is terrible. The sky is falling.’

I think part of what’s happened is this combination of the writing of headlines with the goal of producing engagement. Coming in contact with social media feeds that are designed to keep us in that scroll, the result is that really we aren’t going to be reading all the other articles where the argument is, where the nuance is, where the information is. We’ve become a world of headline scanners. We scan the feed for headlines. Whether it’s The New York Times I read a lot of headlines, then I go to Facebook, I read a lot of headlines and maybe I right click and I open a new tab. I think someday I’m going to go back to that article and that’s how I end up with hundreds of browser tabs all the time on my desktop. So that’s a long way of saying that I think it’s important to think about why headlines have turned into this, textually? Who is composing them and what’s the structure of them? And part of what I tried to do with the Doomscroller was to take my daily reading of these headlines and try to rewrite them, to find the essential message from that headline. And I put those in the Doomscroller. And that’s kind of what you see when you scroll, are these rewritten abstractions or generalized versions of what we see all the time, every day.

Søren Pold

I definitely get this! We’ve been through this for over a year now. So how have our cultural and intellectual consideration or understanding of the pandemic shifted over this year, and do you think any of these changes have positive potential, or are something that we should hold on to?

Ben Grosser

Yeah, it’s such a great question. It’s a big question, right? I mean, being in the United States, it’s hard to not think about the part of the cultural context of the pandemic being tied up in race relations and the way in which organizing and focus has maybe shifted even more so into these online spaces, such that collective action becomes more possible. I guess that I’m thinking about the role of video sharing, for example, in the George Floyd murder in the United States last summer and how that’s played out ever since.

And it’s not like these things didn’t exist before. I mean, Rodney King back in the 90s, of course, went on TV. But there’s just a way in which the combination of yeah, we’re on social media, but we’re also all inside in our homes or, you know, so many of us are in our homes and at the very least communicating with others through the social media platforms in particular.

You know, it’s funny, I’m also just thinking about the question, what do I want to keep? That’s part of, I guess, how I’m thinking about your question. It’s like maybe we can start to see the curve changing and there’s the vaccines and there’s potential for different horizons that we can see for getting out of the pandemic. What do I want to keep from the pandemic? What’s good from it? And the truth is, it’s things like this. I mean, like this interview, it’s not that we didn’t do interviews and have meetings and do things online before, but boy, has it become normal that I can give talks and have interactions with people all over the world without the necessity of travelling. And we can participate in events across the world without being in each place. And I’m hopeful that in the future we will continue this, especially as someone who’s often wanting to be in Europe but can’t travel as much as I would like to in other parts of the world, too. I’m hoping that we’ll maintain some of the potential for online interaction, even when we resume physical proximity and gathering. So those are a couple of things I think about.

Søren Pold

Definitely, there’s potential in international collaboration across digital media as we have experienced during the lockdown, but how do digital art forms relate to this situation? Electronic literature, net art, have always been online and mediated, right? And now we’ve been through this period over the last year where virtually all of cultural life has moved online. What do you think about this? Has it changed the way you think about your work and think about producing your work?

Ben Grosser

I first think that it’s important to notice that the social media companies, big tech in general, have had a fantastic profitable period in the last year. It’s really, if I’m Mark Zuckerberg, if I’m Jeff Bezos, you know, this is great. I mean, obviously I’m sure they don’t think death is great. I don’t mean to be flip about that. But just in terms of the effect of taking normalization of living online to another level such that the questioning of platforms now can’t be disconnected from just how ubiquitous they have become. We were certainly at a moment, as the pandemic arrived, when big tech was under more scrutiny than it’s ever been before. A lot of negative press for Facebook, for example, with people worried about the self-esteem health effects on young people on Instagram, just, you know, we could go down the list of all of the major social media platforms.

But when you can’t see your friends, if you’re a high school student or young college student and you can’t just hang out, you know, these platforms become even more essential than ever before. And the thing that I think in regard to this is that what’s happened is even more protection, more protective of the platforms and their role in society. And so for me, that’s something I always want to be questioning and inviting other people to think about critically. People are always asking me, oh do you hate Facebook, for example? A lot of my work is about Facebook and critical of Facebook and critical of Mark Zuckerberg. And I mean, yes, in many ways, sure. But I also have gained a lot from Facebook, and I think that’s the complication that deserves attention, that there are interesting things about it. There’s reasons there’s 3 billion people there. It’s not only because it’s a monopoly and dominant, although that’s a big part of it and kind of its own tactic, the corporation’s tactics. But it’s also about a hunger for connection.

And this moment has elevated that hunger for an online space. So it’s true that my work before was already online, but now it makes even more sense. I will say just a caveat there, though, which is that it’s kind of interesting, I mean, the mobile devices are always a mixed bag for me because a lot of my work takes the form of browser extensions that manipulate sites and platforms, but I can’t really get them to run on the phone. And so there’s been a way in which we’ve been parked in front of desktops, probably as a higher percentage of time, desktops or laptops in the pandemic than we were before. And so in some ways, that creates opportunity for me that doesn’t normally exist, as we are always on our phones when we’re out and about. So maybe I will miss that aspect of it. I don’t know. We’ll see.

Scott Rettberg

It sounds like you’re going to miss the same enslavement that Mark Zuckerberg’s going to miss.

Ben Grosser

That’s a good point, right? Well, I mean, yeah, that’s well taken. That’s funny.

Søren Pold

The question was also in a way meant for you as a net artist – generally, electronic literature, net art has been in the margin, right, compared to the Picassos… So it’s also a question of whether this lockdown of the ‘away-from-keyboard’ reality is an opportunity for net art and software art?

Ben Grosser

Yeah, no, that’s a great question. I would love to say that I think that everybody stuck online more than ever has created this great panacea for net art. When it comes to work that is critical of the platforms we depend on, there is more interest in that kind of work, perhaps in the last year, but it isn’t the explosion I might hope for, given the ways in which we’re worse off. Given how much usage has probably increased of net based technologies, you know, in terms of electronic literature, I’d probably be interested to hear you all speak on the wider role and the way in which this moment has perhaps increased hunger or acceptance of or interest in electronic literature as a genre, but certainly net art.

I mean, like, it’s hard to hear this question and not think about the last two or three week kind of frenzy going on around NFTs and blockchain and crypto art in general. The Beeple 5,000 image piece that just auctioned for 69 million dollars at Christie’s and as an NFT, as a non-fungible token. And there’s been just an explosion of writing and thinking about the role of what crypto art means, I think, for digital art in general, and I’m very critical of what I think it’s probably going to produce and what I already see it producing, which is kind of taking some of the – for me, one of the things digital art, net art, electronic literature has had going for it is it’s easy to distribute, people can have the same, in many cases, the same aesthetic experience, no matter where they are on the planet, that was the one intended by the person who created it.

And it hasn’t really been ramped up in the art market, in the speculative finance market forces of the conventional art market or the conventional literature space. That’s a good thing from my perspective. It creates a lot of space for critique and for critical work that isn’t playing to the crowd. I mean, maybe it’s not good for artists having income. So that’s a problem. But the truth is most of the conventional art market does not help artists have income. It’s a high inequality space where there’s a few at the top making millions, and then there’s a bunch of people at the bottom, 99 percent of the people at the bottom making, you know, 5,000, 10,000 dollars a year, whatever it might be. And so I’m concerned that this whole frenzy around crypto art is going to, in fact, is already producing a kind of get rich quick focus where people are looking for what did people do to be successful in this new space? What are the strategies to make work, what’s the formula to get that 69 million dollar payout? It’s like when there’s a big lotto, people try to figure out how do I win the lotto? And that’s, I think, been true in the conventional art market. I don’t want that to move into the digital art space.

And no matter what, that is not a great producer of critical work. That’s a great producer of following work, of non-critical work, of safe work, because all of a sudden the audience is not, in my case, everyday users of technology that examine their own experience and relations with tech. Instead it becomes more about “how do I make something that the speculative finance crowd will see as art?” And so if it doesn’t look like art, then it maybe isn’t going to do well in the crypto art space. So anyway, that’s maybe a bit of a tangent, but it’s hard for me to not go there.

Scott Rettberg

My son asked me about the Beeple thing the other day, my 11-year-old son. And, you know, he was asking what is this all about? I was like, well, it’s just proof that currency has always been an invention. And that art, from one perspective, is simply a commodity. And that’s sort of sad.

Anna Nacher

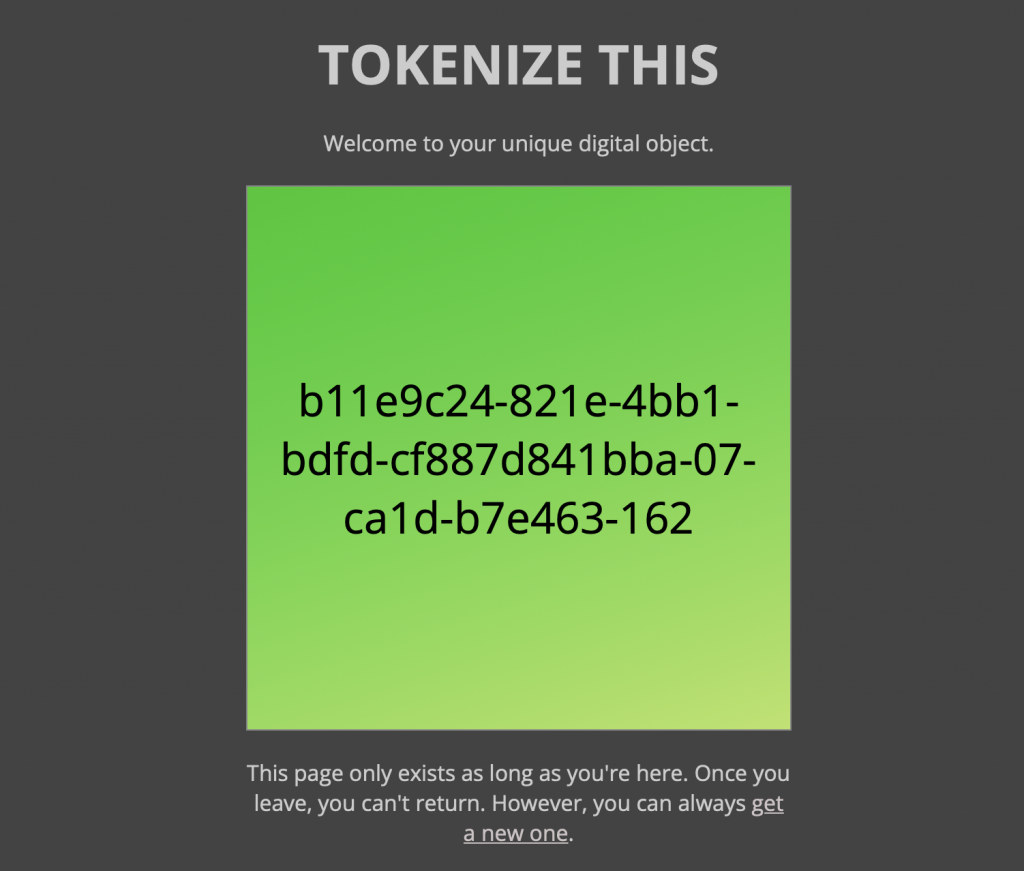

And I have a question concerning Tokenize This, the project I really like. So, my question is, is it about art at all? With NFT it feels sometimes like the art actually sells cryptocurrency rather than the other way round. That would be my doubt about NFT. What do you think about it?

Ben Grosser

You mean specifically for the piece that I made, or even more?

Anna Nacher

No, in general. Tokenize This is different.

Ben Grosser

Yeah. I think what’s scary about it from my perspective, is the symbiotic relationship that expands and develops between currency and finance and any object that could become the speculative basis for playing with currency. There’s been a lot of critique in the last couple of weeks about the ecological costs of crypto art. Understandably. It can take the energy consumption of an EU family of four, this is Everest Pipkin’s work, right? Looking at just how much energy it takes for a single NFT to be minted.

I honestly think that has produced discussion that we’re going to move to other methods called proof of stake which will be less ecologically devastating, and require less energy for cryptocurrency. So it’s going to get better over time. But the truth is, I think the fact that this currency is high cost for the planet is part of what makes it alluring to the people who would like to play in this space. The people who have 69 million dollars to go speculate on a token of ownership over a JPEG. And artists are, for better or for worse, great at producing lots of things. I mean, that’s what they do, right? So it’s the relationship between the desire to purchase, the desire to play in a currency space, combined with net art. It used to be that painters still had to get canvas, some wood and some paint, get in the studio and make something. Sure, they can turn to a factory kind of operation. But now we can just write an algorithm that generates endless digital images that are unique. I think that’s part of what freaks me out.

Anna Nacher

Yeah. I must also say that I am a bit worried about your project - and I’m referring to Tokenize This. Aren’t you afraid that making ephemerality so visibly objectified may be dangerous? I mean while making ephemerality digitally objectified, I would be afraid that at some point it’s going to be monetized again. The more ephemeral means the more expensive. This kind of question crossed my mind when I saw Tokenize This.

Ben Grosser

Yeah, I appreciate that. I would not be surprised if someone hasn’t already in some way tried to tokenize Tokenize This and maybe it’s already selling on crypto art markets. From my perspective, what I’m trying to do with that work, and I think it’s worth the risk, is to take ephemerality and put it in the foreground. To sort of put a stake in the ground: to say to the crypto art evangelists that this challenges the way you’re thinking about the world.

I guess that it’s important to remember that impermanence is a permanent feature of the digital. That we tend to think of all of these digital things as lasting. But really it’s all ephemeral. Putting it in the cloud, having it on Amazon Web services, whatever it might be, wherever all these platforms store the data, the moment there’s a power crisis or an energy crisis or a natural disaster, or even just cold weather in the case of Texas in the United States a few weeks ago with its poor regulation around infrastructure. This is not permanent material.

And that’s true of the NFTs that everybody is crazed about just as much as it is what Tokenize This produces in reaction to it. So, I certainly don’t mean to trivialize in any way. To me, it’s one of the best things about it that we can change it, that it doesn’t stay the same, that we can delete it, we can move it, and in that flick of a button, just as easy as it is to make it in some cases.

Søren Pold

So we’re actually getting into this discussion about platforms, at least in the questions which we’ve discussed. So getting back to our list of questions, a question that’s almost trivial to ask you: I guess that’s not news that we’ve moved from this sort of open, wild Internet of the 90s and 2000s, and where net art in a way came from, to this platform-based Internet today with social media, streaming platforms, mobile apps, etc. How do you feel about working in these platforms? Because that’s what you do, right?

Ben Grosser

Yeah. I think that’s the right way to adapt the question. I mean, it makes a lot of sense to me. I will say, you know, I continue to kind of revisit for myself what is the value, what is the relative value, for example, of making work in platforms versus, say, erecting, building, imagining alternatives to platforms? And it’s not that I don’t do the latter. I’m working on a project now that is relevant to that side of the equation. But for me, the reason it’s important to play in platforms, even though it’s a contentious, unreliable space that is very much at the whim of the platform, is because it’s where the people are.

One of the things I hope to do with the work that I make is to help people develop their own critical lens on what it means to be a user of a platform. That is a relationship that is, from the platform’s perspective, a hyper-designed, hyper-analyzed relationship that is all about the production of certain kinds of behaviour from the user. From our perspective, as users, you get a Facebook account and you friend people and then you become part of groups and then you have a feed and you like or you love or you haha, or you sad, you care, you wow, you’re angry, etc. But these, you know, as with all software, this is quoting Matthew Fuller, but these are the conditions of possibility that the designs of software set for us. And it’s so hard as users to keep in mind that the options that are there are there for a reason and they’re there for the benefit of the platform, not for the benefit of the user. It’s not that they necessarily mean to generate anti-benefit. I mean, there has to be something attractive about the platform, but only so much as it requires to keep us there. And from then on, it’s about the generation of—the way I think about it is, the goal of most platforms is the generation of more. More users, more data, more activity, more focus on the platform and away from everything else, more focus on the numbers. I’m often thinking about the metrics that count the likes and the shares, et cetera, and the followers.

So, to play in this space, to help everyday users start to develop some criticality around their own experience of these platforms, I think it’s important to play in the platforms, even though that means that when I make it work today, it might be broken tomorrow and I maybe have to fix it tomorrow. And sometimes my works go broken for a while, then I get back to them when I can fix them up and whatnot. Instagram has come after me and got my work kicked off the Chrome Web store. Facebook has come after me and got my work kicked off the Chrome Web store. But to me that’s a good thing. That’s a mark that I’m doing something. I mean, the production of cease and desist letters is not a goal. I think that’s a little too easy. It’s finding that middle space where your work persists, but they don’t really come after you.

So anyway, that’s maybe one answer to your question. I was talking with Geert Lovink about NFTs recently and thinking about, well, is it necessary to start making a crypto art space in order to play with this critically? Like what if you were to put something up for sale on a crypto market as part of a critical approach? And, his point was, well, you can’t play in these spaces without getting dirty. Like, how are you going to be critical of it without in some way getting in the middle of it? And I do think this is, like sometimes it’s the difference between some art and art strategies and also some kinds of new media studies, ways of looking at the world. It’s like some people stand aside from a space or stand outside of a space or a platform and they look at it and they use that vantage point as a very valuable position from which to critically evaluate what’s happening and to analyze what it is. I guess I take the opposite approach, which is to live in the platform, to really take my own affective experience of a platform as inspiration for how to manipulate, think about critically, what is happening. They both have their advantages and disadvantages.

Søren Pold

Following up on this, you said two things during the interview. One thing is that there is a critical reflection on these platforms. Actually, I remember even hearing Shoshana Zuboff saying that she thinks we are on the right track, actually. We are starting to ask these questions that we weren’t asking some years back, you know, everybody including people outside our field are starting to ask such questions, not only us. And then you say that you want to create something that helps people become critical. So what is this critical reader or user then? How does he or she look like and behave? You know, how are we critical users of platforms?

Ben Grosser

Yeah, that’s a tricky question, but it’s a great question. It’s certainly one of the right ones. I guess that those of us who make art in this space or other genres of creative work, are not going to somehow produce a user base of people who are thinking about it critically in the same way that media studies theorists or net artists do – certainly that’s not what I’m talking about.

What I hope to help people develop for themselves, is never being able to get lost in a platform for very long without there being some side of their brain that is reflective on the experience they’re having. In thinking about the fact, and this would be going to your work, Søren, that what’s in front of us is a very slick, easy interface, just click a few buttons and it generates all this stuff and all these things happen. It feels natural at this point. But there is nothing natural about it. The slickness and the sensuousness of scrolling and moving on these devices, for example. That feels the way it does because it’s in service of the platform itself, you know, to try and make it as literal as possible. In terms of an example, when Facebook introduced reactions, when Facebook went from the like button to the six reactions that included the like button, a lot of people—what had been happening before that moment was everybody clamouring for a don’t like button, that was the big question. Will Facebook introduce a don’t like button? People want a don’t like button. We need to be able to have a way to express we don’t like something. And Facebook didn’t answer that with a don’t like button. They came out with all these other things, these emotions.

I want people to have enough reflectiveness with their experience of platforms that when they see a new feature, one of their first questions is: for who? Who is that new feature for, is it for me or is it for them? And if I help some number of people develop that for themselves, then I feel like I’ve had a good day. You know, to read the interface, to read these interfaces in ways that, like, we would read literature, like we’re taught to read literature from kind high school on, which is to not just think about the literal words on the page, but to think about what does it mean? What does this add up to in interpretive ways?

Scott Rettberg

Yeah, I always say that one of the functions of a lot of the interesting electronic literature and digital art is to sort of go back to the classical idea of defamiliarization. The idea that what literature is meant to do is to make an experience that’s right in front of us strange to us. And I think that’s what I really like about a lot of your projects, is that that’s where you’re sort of getting to, where we’re getting the criticality from, is seeing from within the interface that you’re critiquing what the interface is doing to us. That’s an act of defamiliarization.

Ben Grosser

Yeah, I appreciate that. I mean, I certainly think my Demetricator projects play on that, for example, just hiding the numbers that we’re used to looking at. It means you don’t see how many likes you have, but really what it produces is an awareness of how much attention you were paying to the numbers and where the numbers are in the interface in the first place. And you can’t— it’s like if someone cuts down a tree in your neighborhood, now, all of a sudden you realize there was a big tree there. The change makes it feel strange and unusual. Then you have to think about what’s different and why.

Søren Pold

Thanks! I definitely agree with Scott on how your work unwraps interfaces from within in an intelligent and often also humorous kind of way. The next questions are more sort of on your artistic community and social environment. The question is how the pandemic has changed your sense of artistic community and social environment. Well, you talked about earlier, that we could actually do these kind of things now, meeting and collaborating internationally through online media, so maybe that’s the positive. I guess there are negative aspects as well?

Ben Grosser

Yeah. I mean, certainly it’s hard for me to not think about the negative aspects of my interactions as a professor with my own university. I mean, my interaction with my students has largely been—it’s starting to change now, but it’s largely been online. Certainly I’ve taught my courses online as most of us have or many of us have. And so much of what happens, you know, I, like many of you, have spent many years developing techniques, pedagogical techniques in the classroom that are very much based on reading humans in a space and getting a sense of whether they understand something or are they thinking about a question, and really reading the body language of people because they aren’t always necessarily ready to come out and say, and using that to kind of guide when I elaborate, when I move faster, when I move slower, when I add something. And that’s just been broken in the Zoom world. When we all get together in the Zoom conference world, our faculty world, it looks like this. But when I get together on Zoom with my students, it’s one box with me in it and maybe a student or two who’s got their camera on and then a bunch of black boxes with text in them. It’s just not the same kind of interactions. And then there’s also the aspect that so much of what happens in the university between myself and students is not in the classroom. It’s after the class. It’s before the class. It’s in the hall. It’s at the talk. It’s at the coffee shop. It’s, you know, standing outside the grad studios and kind of thinking in those ways in those times. And those have all gone missing. Same with my faculty colleagues. I have a few, you know, that I’ve kept a social connection with through the Zoom, but with a lot of them, it’s very businesslike right now. I lost that with faculty, too, right? I don’t have the before the meeting, the after the meeting, or the you run into them in the office kind of thing. And that’s had a negative effect in terms of university culture. It makes it feel even more business-like than it was before, perhaps more transactional. So, like those aspects are kind of interesting, right? So maybe it’s expanded my connection or made more opportunities for connection to those who are further away and made less connections for those who are nearby. Even though I know they’re down the street, they’re two miles away. I don’t see them. But I might be at a conference more often that I never would have gone to, or a talk I couldn’t have attended because, you know, the talks happened in other universities and other places that now I can just go to.

Søren Pold

And then it’s something that you also touched upon this theme that the pandemic relates to, or at least has come at, a time of larger crises, of course, the climate crisis and the Black Lives Matter and also in Europe, discussions about racism, sexism. So, the question is really, do you see any connection and are these other crises also reflected in your work or how do you look at that?

Ben Grosser

I think they are. I’m not often taking on say sexism or racism directly with a particular work. But I think that platforms, as our way of interacting with the world, have a dramatic effect on some of these questions. They’ve created some opportunities and also created plenty of negatives as well. Some of the opportunities, of course, are awareness and discussion. And I think about the #metoo movement or I think about Black Lives Matter and organizing and visibility; new technologies have had some positive effects there in terms of just helping people become aware of what was already happening, or we’re making it impossible to continue ignoring some of these things.

But at the same time, the platforms have created dramatic negatives for the proliferation, the explosion of racism, sexism, ableism, homophobia, transphobia, et cetera. Facebook is a big player in this space, where its advancement of groups and it’s attempts to pivot off of the 2016 presidential election in the United States by focusing on communities and away from connecting everyone. When they said let’s get more local, let’s get more specialized, it just enabled things like QAnon to proliferate and emerge such that white supremacists can now gather on platforms and feel free to speak openly and casually about their perspective on the world. The relationship between a figure like Trump as a social media user, as a Twitter user, and the way those racist messages proliferate is easily advanced through algorithmic feeds. And I think algorithmic feeds play a big role on Facebook in this case, too. The classic filter bubble is the original description of this problem. But it’s so much more complicated now. We all see a picture of the world that is very specific, a picture that matches what the algorithm already thinks we want. Such that, even when people started posting their vaccination card pictures in the United States, a lot of them would say, well, this is so that people who are on the fence about vaccination will see that I got a vaccination and maybe then they’ll get a vaccination. And my reaction to that is, well, nobody who thinks differently than you about vaccination is probably going to see your picture because the algorithms already figured out that they aren’t interested in that photograph. And so from my perspective, through my work, I’m interested in how the designs of software affect how we think, what we do on a regular daily basis, how we think about ourselves, how we think about others, how we think about what the world is, what’s possible, what’s available, and in that respect, I feel like it relates to all these social ills that you’re talking about.

Scott Rettberg

I guess I was just thinking something about the Trump era—I think it wasn’t just Trump. I think you’re right that it was also software. But when I was, sort of out of interest, I kept following, you know, I had these discussions and debates with people I grew up with who had different political views than my own. And at a certain point, it occurred to me that I don’t think that they care about truth value. And I think that there was this shift, not that everyone was suddenly deluded, but the shift was that well now a tweet is just a tweet. And what you do with tweets is you advocate for your position by just producing discourse and reproducing discourse. You’re no longer making a claim to truth value, which is, yeah, I think that’s what’s happened on social media to the idea of truth.

Anna Nacher

And it is happening globally. I mean, in Poland, I’ve been watching exactly the same debates, exactly the same discourse, the same arguments, the same dynamics. Yeah, it was so much Trump-like even if it concerned an entirely different political situation, I mean, roughly similar to what was going on in the U.S. but the similarity of the discourse was striking. So definitely the algorithmic culture probably is a major factor in this global shift, I would say.

Ben Grosser

Yeah, I appreciate both of those. I think you’re both right. I also think it’s a symbiotic relationship between platforms and between individuals on platforms. Trump can make a tweet and sure, it’s a lie—he made 30,000 of them in his presidency or whatever the number is (The Washington Post counted; I don’t remember the number). But, then it proliferates in some way on Twitter, and then it gets posted on Facebook and then it circulates in groups where people can just play with it in such a way that it doesn’t matter if it’s real or not. It becomes a way of continuing to be racist or, it feeds the desire to see the other as bad and not equal. Before platforms it’s not that you couldn’t go to your own media sources; you could pick up the conservative paper or the liberal paper, whatever it was, and you could have friends that maybe all agree with you in a particular perspective or all perspectives. But now it’s not just that you can seek it out or you can have a conversation. Now it’s fed to you over and over continuously as fast as possible. And it’s testing you, to see does this get you to focus more? Does this lie work? How about this lie, and this lie? And then it just gives you more of those kinds of lies, if that’s what is really activating you to stay on the platforms.

Anna Nacher

And there is no way to actually clarify anything like, you know, a lie as just a story. I mean, the more engaging, the more effective. So it’s, like Scott said, it is not about truth value anymore. And that’s what is really, I think, dramatic. So in a way, it is, you know, politics. I mean, politics is dead basically from this standpoint.

Søren Pold

It’s a very interesting discussion, and maybe we should get on and finish this interview, but I just wanted to interject that, in well, in large parts of Europe, we of course, worried with Trump getting elected, with Brexit and Poland, Hungary. And now it’s just going down the drain. And then and in some important ways also it hasn’t, right? That’s also part of the story. Yeah, you’ve got a new president as well. I’m just saying this is not to argue that things aren’t bad in Poland because of course they are. But that it’s, well, it’s not maybe just sort of a totally determined factor, right? Which maybe speaks back to you. I’m not sort of arguing that that’s because we’re more critical in Denmark or something, but there might be different modes of reading or modes of using, in ways that, well, some countries haven’t fallen into that trap, at least not in the same way. Or maybe we were warned at the right stage, because we’ve been there with xenophobia and stuff, and it’s not that it’s cleared out either, but it’s just that we didn’t at least get so far down the rabbit hole all over Europe. Usually we get the same kind of political movement in Denmark five years after the US, but we don’t, we haven’t gotten our Trump. At least yet.

Ben Grosser

Yeah, I mean, Anna just said in the chat that things are not all bad. The problem is, I don’t think we have found the effective way to tackle algorithmic culture. I hope you don’t mind me reading your chat here out loud, because I think this is the case. Like, I’m in agreement with that. It’s, to me, that we got rid of Trump, then we have Biden in a really different—like, things have changed very quickly in the United States with the pandemic, for example. And the response. To me, it feels like we just barely squeaked that out. Despite tremendous organization and tremendous effort and massive awareness through social media platforms and activation of more voters than ever and a higher voter percentage, even in our low voter percentage kind of culture here in the United States, than ever. And Trump, for all of his ability to manipulate, I think it isn’t necessarily nearly as capable as somebody else could be. Now that they’ve seen how little truth has to matter, how much lies can be the currency of politics. So my fear is that it’s this balance that we have to somehow get a handle on the role of platforms to misinform, to disinform, and the way in which they’re utilized for that purpose and the potential that they hold for organization and and informing. It’s a complicated case. But I agree with you, it’s a moment of optimism. I mean, I certainly feel a lot more optimistic. I was trying to figure out how I could move out of the country in October 2020. And I’m not currently trying to figure that out today.

Søren Pold

We are getting towards the end of our questions, though I was thinking a question that in a way we haven’t talked so much about is this question about locality versus globality. Several of the artists that we are also exhibiting have made works where they take photos, they are walking in the street, and they do different work than you do, but anyhow, the question could be, how this local lockdown where you sort of have to stay in your house and you couldn’t travel, how has that made an impact? How do you think about that? You know, the different dimensions between our attachment to the local versus global, which, of course, you take the same walking trip every day now because that’s what you can do, right?

Ben Grosser

Yeah, it’s so funny. I mean, it’s like my attachment to the local, I almost feel like it’s been diminished. I care about the local. My community is local. But I haven’t seen, as we talked about before, my local community. I’ve seen less than ever. And that’s a very strange aspect of it. And if you go out for your daily walk or whatever it might be, it’s uplifting now. But there was a time where it’s like, well, you don’t necessarily know even the protocols of how to interact with someone you might run into on that daily walk, where, maybe not everybody has the same level of comfort with that. I certainly think about how, from the early days of the pandemic, people just didn’t know what to do exactly. I’m an introvert, so, at first, the prospect was of just living in my box, in the Midwest United States, and not in a city—I live in a college town, which means I have a large house for the same price people pay for studio apartments in cities. And I have plenty of space. I have a nice big backyard. I have a studio. I have other rooms and my spouse and I can get distance from each other. And then we can come together. I’ve adapted to living in the box. But what I think is hard to characterize, what a lot of us will be getting a handle on shortly, is just how much we have changed, how much our perspective on the world has changed by so thoroughly adapting to this new way of living and what might emerge once we are able to engage in a lot of the activities we were all longing for. Travel, for example. Gathering, social gathering, artistic gathering, performance, music. These are things that I really miss and, you know, the ability to have an experience with someone of the same kind of thing or to have different experiences, but in the same space of, say, an artistic performance. Those things can really feed us and change how we feel and change how we see things. And whether it’s a reading or music or even just a movie—like going to a movie is really different than seeing it through the box within the box. That’s how I’m thinking about it anyway, about this difference.

Søren Pold

Yeah, I don’t know the last question, I think you kind of answered it, but this was this question about what do you miss most about your life before the pandemic and what will you miss about your current life after the pandemic? In a way, you have answered it.

Ben Grosser

Yeah, I think I have in a lot of ways. Maybe my biggest answer is I’m not sure I know anymore. You know, it’s like I think in the first month or two or three of the pandemic, it was so easy to answer that question of what do I most miss? What is it I can’t wait to get back to? I’ve adapted so thoroughly. You know, I’ve had conversations with my spouse, asking what’s the first thing you want to do when the vaccine is fully effective and everything’s done and you’re vaccinated and it’s all good? My answer was there’s a store I’ve been wanting to go to that I didn’t feel comfortable going to. It’s like my imagination for what not living in the box could be has diminished dramatically over a year. And of course, I can imagine. I’ve talked about all the things I look forward to, I do. But the world isn’t just going to switch on a dime back to “now there’s no pandemic.” We’re talking about teaching in person in the fall, but it’s with masks and social distance and it’s still contentious. We’re not exactly sure how it’s going to work and what’s the ventilation and all these kinds of things. So I hope that it will seem obvious when it’s actually here for me and for all of us. But I worry that we have so thoroughly adapted that it will be harder for me to remember or to engage in those things, although I guess I have to presume that we’ll adapt back once the opportunities are here, that when I can really just go anywhere I won’t have any trouble thinking of answers to that question.

Anna Nacher

Maybe by next year it will seem like were just living in a performance during the pandemic.

Ben Grosser

I know. But, like I think that’s a good way to think about it, because if you live a performance long enough, it becomes not a performance anymore and it doesn’t feel like a performance anymore. And, so I don’t feel like I’m necessarily performing the pandemic. I’m just living the pandemic. And performing not pandemic is the thing that comes next.

Scott Rettberg

Well, it’ll be interesting to see if we can perform non-pandemic. I’m looking forward to, like, you know, the idea of getting on a plane without apprehension.

Ben Grosser

Right.

Anna Nacher

Or getting on the plane in the first place.

Scott Rettberg

Yeah. Yeah. Sort of this idea of, you know, it’s going to be around for a long time. And it’s funny because I think there might be an adjustment back in a way for people of our age, people, you know, people of our age and a bit younger. But for kids, you know, I look at my 11-year-old, and my 13-year-old, and you just think about what a chunk of life this is and how what’s normal anymore is going to be radically affected by this, not for now, but for a long time.

Anna Nacher

But kids are resilient. You could compare, for example, with kids who had the experience of being in the war or being refugees, and most of them suffer from the symptoms of post-traumatic syndrome but at the same time they often overcome their trauma and are capable of succeeding in life.

Scott Rettberg

Yeah, we’re going to live, and there are different levels of trauma…

Søren Pold

You’re right in the sense that, you know, I have a 19-year-old who finishes gymnasium or high school, which is a totally strange thing, because it is this highlight of youth, right, where you have parties and it’s totally not happening and it hasn’t happened for a whole year. But I think also when I look at my students that they’ve got something else. That is, of course, they haven’t slept for a year. You know, that a certain sense of understanding situations and also compassion, that’s been amazing. And hopefully, yeah, they can take that with them. This sense of we were actually together in this, of course, in different ways, but it was like when you heard about this in January last year, you didn’t think it would hit us, right? Perhaps the rest of the world, but hey, we’re rich and we can buy this off somehow. But it did, right? And the next thing is that if we get vaccinated and Africa doesn’t, it’ll hit us again. And we will realize we’re part of the world. And that’s a big thing to realize.

Anna Nacher

And all the superficiality of the Western culture was exposed suddenly, like public health care, I mean, never actually worked anywhere. I mean, nowhere, nowhere. I mean, there’s no country where it worked properly.

Ben Grosser

I do think that’s an opportunity. Think about the United States and the newer different lens on what it means to have a public or what the value is of the public versus the private. You look at the popularity, 75 percent popularity for the recent $1.9 trillion stimulus bill that came out of the Congress that Biden just signed. 75 percent popularity, that’s an unheard of number in a country like the United States that’s always polarized on everything. And so much of that is public, it’s money for the public. And so that’s definitely a change.

But I hear Scott too. I think about my college students and they’re at such a formative moment for who they become, and so I think, there’s the optimistic kind of ways in which it makes visible the world and the connectedness and the relationality. And then there’s also a way in which it has severely derailed mental health in a challenging way. Growth and change and discovery of who one is, who one wants to be and what they want, what kind of paths you want to form in the world; this is often done when you get to emerge out into the world in college and beyond, or at least out of the household that you grew up in. And their experience is really different from being our age where it’s like, well, it’s just this smaller percentage of life. But for them, if they’re 20 years old, it’s not even just 1/20th but more like 1/10th or 1/5th, given how far back we remember of childhood, of having full agency or even less than that in some ways, depending on the kind of culture one grows up in. On how much freedom one emerges into. So it’s a big, big shift in that way.

Scott Rettberg

Yeah, well, I gotta get out of here. I’m actually at the office and every other single light in the humanities building is off and I think they send security guards around pretty soon. But that’s good, maybe we’ll enjoy the New New Deal and hopefully there’ll be another New Deal and hopefully we’ll all get to see each other in person again at some point.

Ben Grosser

Yeah, I really look forward.

Cite this essay

Nacher, Anna, Søren Pold and Scott Rettberg. "Platform In[ter]ventions: an Interview with Ben Grosser" Electronic Book Review, 7 November 2021, https://doi.org/10.7273/9fdq-t667