The Art Object in a Post-Digital World: Some Artistic Tendencies in the Use of Instagram

While defining the art object in a post-digital world, Maria Goichoechea de Jorge observes in media artists a nostalgia for an analogue craftsmanship; a rebellion against machinic perfection; and a resistance to forms of human creativity that propel us into an ever more profound symbiosis with our technological lifeworld.

This paper aims to reflect on two labels that have been used to define sets of artifacts born out of the same context but evoking different connotations. I refer to the terms “post-digital” and “post-internet”. Both terms allude to a post-stage, a leap that announces a cultural shift, perceived by artists but difficult to pinpoint and demarcate with precision, a prefix that might refer to ‘after’ (chronologically) as well as ‘beyond’ (spatially); often used to highlight that what has been superseded is the novelty and exceptionality of the internet and digital technology. Actually, these terms address the fact that digital media is no longer a form of mediation but it has become our ontology, though this new form of being is of such a diffuse, complex and assembled nature, not even Haraway could have anticipated it.

Triggered by impulses of excess and overindulgence, on the one hand, or sustainability and preservation, on the other, post-internet and post-digital art emerge from a networking and tech-savvy sensibility that has altered the relation between artist, audience, and art object.

In particular, I am going to focus on the work of artists that use Instagram as an art gallery for exhibiting their work (Almudena Lobera, Andrés Reisinger, Lucy Hardcastle) or to sabotage the platform from the inside (Amalia Ulman, Cory Arcangel). Bearing a family resemblance to electronic literature, these works also explore the narrative process in the construction of an artist’s identity, the changing territories of human-machine/artist-spectator interactions and digital-analogue materializations. The art objects they produce can be classified as “phygital”, physical/digital constructs that inhabit, in a myriad of different possibilities of mediation and convergence, the physical and the digital spaces of mixed reality.

As artists explore the platform’s potential as exhibition space, advertising site, and conversation aisle, their phygital objects reflect the tensions between a nostalgia for an analogue craftsmanship which rebels against machinic perfection and an interrogation of human creativity that propels us into the future through an ever more profound symbiosis with our technological habitus.

Part I: Defining post-digital and post-internet aesthetics

Let us start by attempting to define what is the meaning attributed to the label “post-digital”, which is the main concept I would like to address. When do we start to hear this term?

It has been around since the year 2000, when electronic music composer Kim Casone, inspired by Negroponte’s sentence “The digital revolution is over,” decided to refer to a type of musical experimentation, emerging from non-academic, self-taught composers, as “postdigital” in his artice “The Aesthetics of Failure.” “The post-digital aesthetic,” according to Casone, “was developed in part as a result of the immersive experience of working in environments suffused with digital technology” (12), but more specifically from the attention paid to the failure of these technologies: system crashes, bugs, glitches, distortion, noise floor…signals that these technologies were as imperfect as the humans who made them, and which were incorporated in the musical compositions.

From that moment, the post-digital has been associated with a process of “amateurization” in art: everybody can become an artist using DIY techniques, low tech, recycled materials and software, found objects and tools lying “around the house.“ Moreover, the post-digital condition requires that the artist, nearly everyone, becomes his or her own agent, using platforms such as Instagram as exhibition venues to attract audiences and make their art viral. Within this framework, we accede to the growing importance of user-generated content in a transmedia ecology, which has exacerbated the overabundance of data, images, videos, and to instil the logic of extruding data, both as creative practice and as a method to attribute cultural value.

As it happens with other words, such as “postmodernism” or “post-pop”, “post-digital” implies, more than anything, a change in attitude. Emerging from a framework in which technology is naturalized, a post-digital aesthetic would be one in which the artist, through his or her creations, provokes a tension that makes visible the interpenetration of digital technology in every layer of our lives. We could say it coexists with the digital and even the pre-digital, but it involves a critical attitude regarding the notion of digital progress, questioning the positivist ideology that assumes technological development as a linear progress: inevitable, neutral and, ultimately, beneficial.

The post-digital attitude has also been associated with a nostalgic retromaniac turn (Cramer), but from the vantage of one who already dominates the present technology. Or we should rather say that a post-digital aesthetic makes the distinction between old and new media obsolete by eclectically appropriating techniques and materials from an array of digital and analogical practices to create something new, at once strangely familiar and awry. It also supposes a turn-of-the-screw regarding previous strategies: moving from technology appropriation, from a Marxist perspective harnessing the power technology can grant us, to reappropriation, as in Tactical Media repurposing existing technology so as to undo Lorde’s statement that the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house; from the promise of fluid identity of the digital age to the body exposition and postproduction (or postdigitalization) of identity in the social networks of the post-digital age. Though sometimes aiming at opposite directions, these practices, as the web 2.0 that provided their entourage, emerged less from the implementation of innovative technologies than from original cocktails of multifarious ingredients. As Joseph Tabbi points out in Post-digital. Dialogues and Debates from electronic book review, vol.1: “At this moment, our post-digital practice might attain novelty through admixtures and concatenations that amount to a reconfiguration, not a reproduction or instrumental deployment, of technologies” (9).

Concurrently, at the beginning of the 21st century, a series of artists began to reflect on the impact of the use of the Internet and its technologies in our life, but using creative venues outside the Internet, returning to the plasticity of objects in the physical space of the gallery. Artist Cory Arcangel explicitly addressed this decision: “It is not until digital technology manifests itself physically that we can easily grasp its effects on our society and the environment” (Greene Naftali np). This type of art that thematises the effects of extensive Internet use in disconnected creative practices was called post-internet art. Marisa Olson, one of its early proponents, describes it as the process of creating art following time spent utilizing and exploring the World Wide Web. What is made after is the product of this excessive computer use or indulgence of the internet. The internet has shifted from being an escapist pastime from the world, to becoming the world one seeks to escape from. She quotes Artie Vierkant’s ‘The Image Object Post-Internet,’ whose own definition of the term describes it as ‘a result of the contemporary moment: inherently informed by ubiquitous authorship, the development of attention as currency, the collapse of physical space in networked culture, and the infinite reproducibility and mutability of digital materials’ (Olson, 61). Brian Droitcour, in his demolishing post “Why I hate post-internet art,” adds: “post-internet art does to art what porn does to sex”, implying that post-internet artists care more about the idea of success in the art world than anything else, no matter how lacking they may be in the craftsmanship abilities one associates with artistic production. According to him, they have mimicked in their pieces the visual vocabulary of product advertising and brand communication strategies that proliferate in the networks. As a result, “It’s boring to be around [post-internet art]. It’s not really sculpture. It doesn’t activate space. It’s frontal, designed to preen for the camera’s lens. It’s an assemblage of some sort, and there’s little excitement in the way objects are placed together, and nothing is well made except for the mass-market products in it.”

Of course, though Droitcour’s criticism of post-internet art might be acutely insightful with regards to its products, one needs to delve deeply into the matter to understand what is valuable in each contribution. But we should also ask: are the post-digital and post-internet aesthetics one and the same, or can we already perceive a division between the good and the bad art along the lines: it is boring and commercial and thus we are going to call it post-internet art, or, it is cool and inspiring, we are going to call it “post-digital”?

In some of the works of the artists we are going to discuss later, these accusations appear as unfair, since they certainly show their virtuosity, both in the traditional arts ‒as in the sculptural works of Almudena Lobera‒ and in their knowledge of code ‒as in the works of Cory Arcangel‒, but what I am particularly interested in analysing is their activation of space. By introducing in the physical space of the gallery the communication habits of the internet networks and platforms, they challenge our perception of the “medium”, both physical and virtual, and highlight its collapse, convergence, and multi-faceted condition.

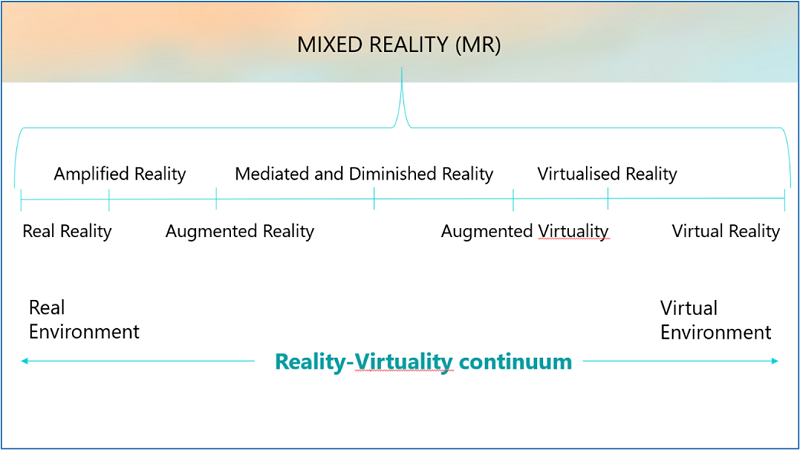

The post-digital aesthetic pierces the dichotomy between the virtual and the physical space, producing artifacts that can no longer be read or enjoyed fully in one or the other space, but exist somewhere in the middle. In fact, the “phygical” artifacts inhabit the realms of what is being called Mixed Reality, which expands along the reality-virtuality continuum (Milgram). As Schnabel proposes, these realms include: Real Reality, Mixed Reality with Amplified Reality, Augmented Reality, Mediated and Diminished Reality, Augmented Virtuality, Virtualised Reality, and Virtual Reality (4).

Thus the “phygital” ontology of postdigital art is not of a single quality, but rather it stretches along a spectrum of possibilities and positions itself along the multiplicity of layers that form this hybrid, mixed, reality: physical objects in digital environments, digital objects in physical environments, “phygital objects” existing at the same time in both, physical and digital spaces, AR artifacts complementing the incomplete physical object or plane of existence, digital objects that have cannibalized an analogical technique or that propose a reencounter with the physical plane in trompe l’oeil materializations, etc. The range of possibilities seems to be as wide as the imagination of the artist, but each combination is indirectly posing questions and positioning itself regarding our conception of reality and the correct balance between ourselves and our technological prostheses.

Moreover, to be really post-digital, these artifacts also have to be submitted to post-digital processes, operations that imbue them with an extra layer of surreality and imagination. Through our study of a few post-digital artists, we are going to attempt to pinpoint some of these processes.

Part II: Post-digital processes and Instagram

- Recycling technological detritus:

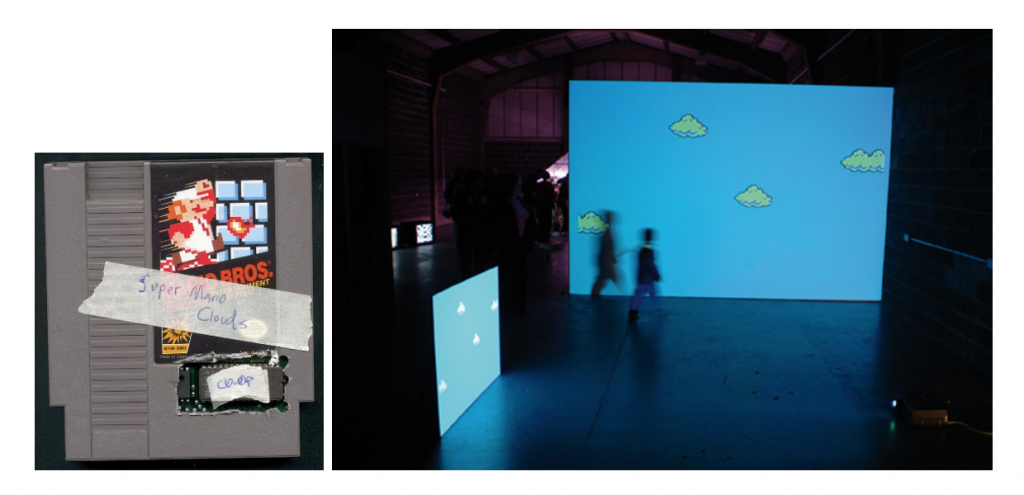

By nostalgically recycling and repurposing old media and technology, post-digital artists highlight the speed with which the capitalist economy makes everything obsolete. Artist Cory Arcangel, for example, seems to have found the proper amount of time one needs to go back to make the retro use of old programs and technology “cool” again, and that is six years. In one of his most famous works, “Super Mario Clouds” (2002), he alters the graphic card of the game so that all the graphics are eliminated except the background, a blue sky with moving clouds (Fig. 2). The hacked video of the clouds is then projected on different screens that surround the spectators, enveloping them in the game scenery. The inserted difference is not only that all other graphics have been eliminated, divesting of purpose the spectators’ wondering, but that the projection has no sound, and the rapid pace of Mario Bros has been slowed down dramatically, so, unlike its frantic protagonist, the viewer can enjoy the artificial sky.

This interesting move of isolating the background is also shared with Casone’s post-digital electronic music composers, for whom concepts such as “detritus,” “by-product,” and “background” or (“horizon”) are the new focus of their attention. As Casone writes: “the basic composition of “background” is comprised of data we filter out to focus on our immediate surroundings. The data hidden in our perceptual “blind spot” contains worlds waiting to be explored” (13-14). Choosing to shift our focus there will involve exploring the boundary of “normal” functions and uses of software. It will also allow us to pay more attention to that which we discard: the “detritus” of contemporary society may have more to say about us than the perfected piece of art.

- Post-digital ekphrasis: Recontextualizing the platform’s communicative strategies.

Spanish artist Almudena Lobera (1984-) puts a frame to the background, the landscape, so that we can become aware of the prominence it has achieved. However, the viewer is not there: we are only seeing the picture, which has been emptied of human figures, helping us reflect on the simulacra, or the second-hand nature, of our quotidian experiences. This image also represents the transfer of receptive modes across media and the impossibility of an unmediated glance.

Lobera, a plastic artist that connects classical sculpture and still-life painting with computer programs, has become relevant to Spanish audiences thanks to her active role in Instagram, where she communicates frequently with her audience, and, following Arcangel postdigital tendencies, she also feels compelled to bring these digital consumption and communication modes to the physical gallery. In her work “Stories“ (2018), she proposes another way of visiting an art exhibition, modifying the logic of the location of the work, the space, and the viewer. In this case, her work will be the one that moves by means of a conveyor belt parallel to the perimeter of the room floor, moving continuously with a sample of pieces located in it. These pieces, selected and organized so that the spectator can construct his or her own narrative, compose a unitary exhibition inside another. The overarching one mimics the exploration of art pieces in Instagram ‒moving from one piece to another with a finger‒ and reminds the viewer that the exhibition continues living in other spaces. As spectator, you are propelled to take an active role as you let the exhibition pass in front of you and are invited to record it with your smartphone, uploading the video to your own “stories” in Instagram (Fig. 4).

With this project, Almudena Lobera wants to transmit “a critical and ironic staging of the prevailing consumer and communication mechanisms in our days”. In this case, the virtual spaces of the internet and the physical space of the gallery are clearly demarcated, though the modes of communication and image consumption of both spaces contaminate one another in an endless cycle of conspicuous consumption and production.

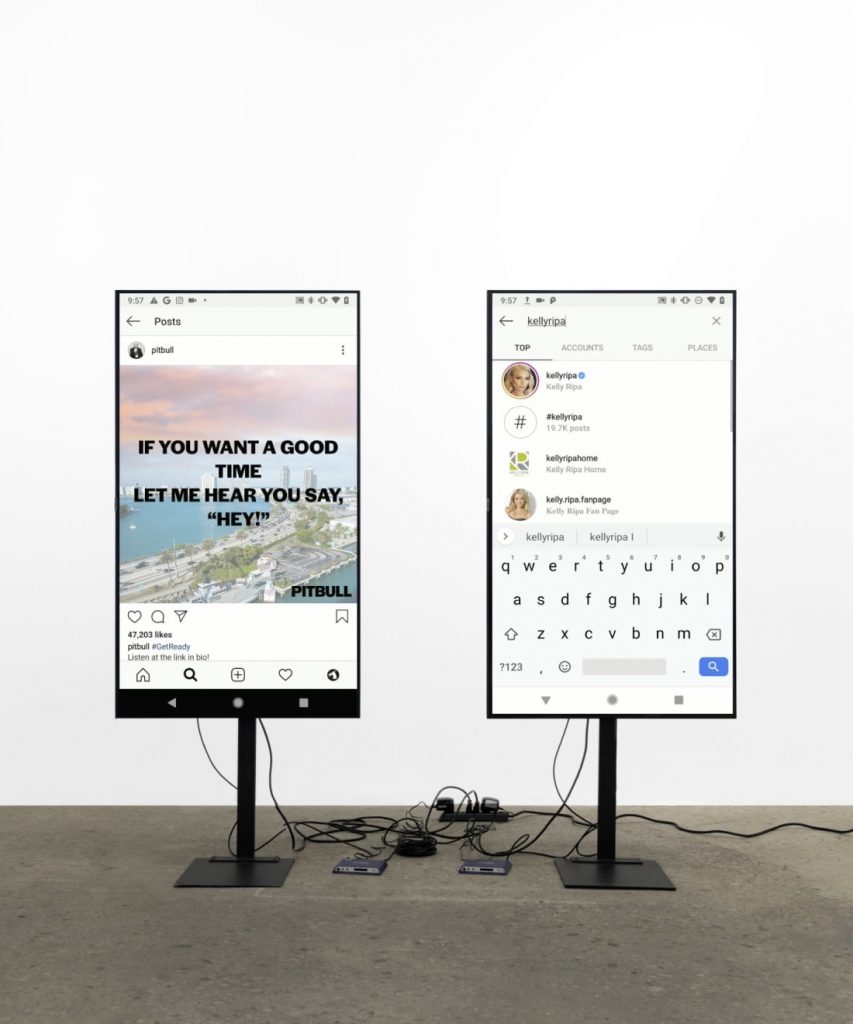

Cory Arcangel, −whose main approach is to intervene and appropriate technological gadgets, introducing a change, sometimes a glitch, to make the familiar turn uncanny−, has also a series of pieces in which he externalizes and intervenes Instagram’s communication practices using bots. As in we deliver / the king checked by the queen or in the work of unpronounceable name in fig. 5, Arcangel presents video recordings of automated performances in Instagram, producing nonsensical and disturbing pieces that completely obliterate aesthetic contemplation.

Curiously enough, Marisa Olson describes post-internet art as coming from “a post-ekphrastic image philosophy”, a moment of discernment that the image could speak for itself metareflexively, without the need for words, and thus turning the rhetorical exercise of “ekphrasis” obsolete. However, as Cecilia Lindhé has observed, the concept of ekphrasis needs to be actualized through the prism of digital art and literature, since print culture has delimited its classical emphasis on energeia (vividness) to focus on the dominion of the printed word over the image. Thus,

[t]he occurrence of visual elements in VR-environments, digital art and literature, could, with Bolter, Ryan and Grau, be said to deny, or make ekphrasis a redundant concept, but this is only if we apply the print-based definition of the term and do not take the immediacy, performativity and multisensory circumstances of rhetoric into account. (par.14).

As we have seen in the work of Arcangel and Lobera, this intermedial practice is metamorphosed into a particular kind of post-digital ekphrasis when, for example, the artist uses another medium (the art exhibit) to describe Instagram’s image consumption habits or uses Instagram for a purpose for which it was not originally designed (a bot performance), and, in this way, exposes the perversion of the platform’s communicative strategies. I observe a pattern in these manipulations of the spectator’s expectations that moves away from a type of digital ekphrasis associated with a return to its classical counterpart a descriptive mode which vividly transmits an experience “through the interaction between visual, verbal, auditive and kinetic elements” (Lindhé, par. 13), toward a post-digital ekphrasis, which turns out to be something which Robert Fletcher insightfully recognizes in relation to augmented reality: “an intermedial disruption of a dominant perceptual regime” (309).

- Augmented virtuality or how to regain the artistic(-commercial) aura in Instagram.

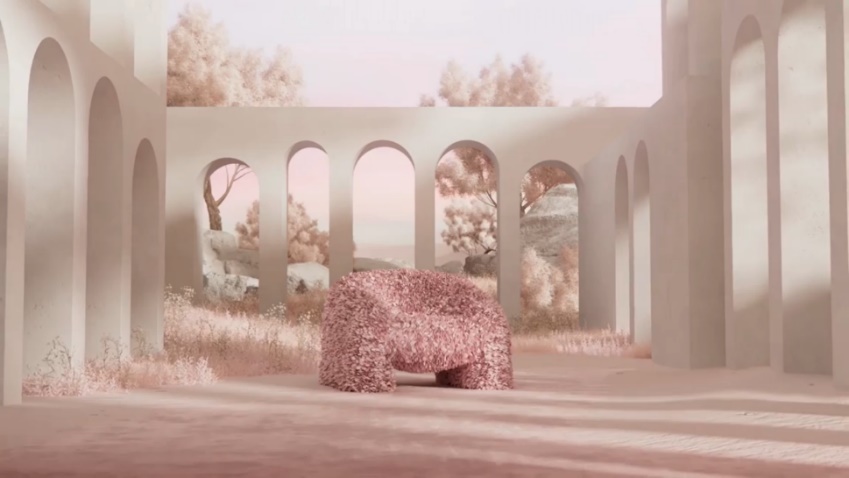

Andrés Reisinger, a Barcelona-based 3D designer has also become a referent in post-digital artifacts, using Instagram as communication venue and virtual gallery, he introduces physical objects in 3D virtual spaces of a surreal quality to recreate a poetic background in which these objects obtain their sense of belonging. In this case, the physical object, a “sculptural” armchair (Fig. 6) for example, is inscribed in the virtual plane to the point that it loses its connection with the real, material world, and acquires an ethereal aura. The aura of the art object is regained through its virtualization. Instead of appealing to a unique existence in the physical space and time, the digital space provides for a new sensory experience of distance between the viewer and the object.

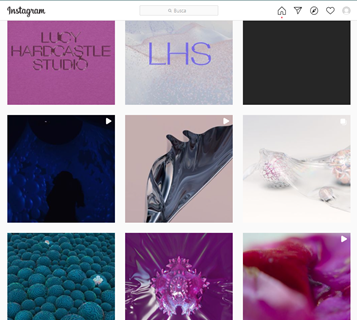

Lucy Hardcastle Studio, based in London and with nearly 8000 followers in Instagram, investigates the tensions between technology and traditional craft. As they observe in the description of one of their projects, their inspiration is drawn from the post-internet ethos “of being constantly connected and constantly seeking visual gratification”. In this case, Hardcastle, like Reisinger, is inspired by online digital art to create physical objects, in this case printed fabrics, but her intention is to confront, play a mirror game between the physical and the digital plane, challenging in the process the perfectionism in both the fashion and digital design worlds. The journey moves from the qualities of physical objects ‒like liquids, ice, soft materials‒ and their textures, which are then conveyed to the digital objects, such as images and 3D sculptures, through rendering software, and then suffused back in physical materials, the printed fabrics that are used to create wallpapers, rugs, curtains, etc. The online object is recreated physically, confronting the differences in materiality between the two planes, the digital and the physical, one the clone of the other and back again. The result is a series of printed fabrics with illusionary textures and digital tromp l’oeil effects, since the end products lack those qualities that have been recreated in 2D, such as ripples, roughness, contours, and even temperatures. The result establishes also a game with the spectator that consumes these images through Instagram, since it becomes a challenge to decipher which is the digital object and which is a photograph of a physical one, reproducing the digital characteristics.

As we have seen, Lobera places the digital consumption and communication habits in the physical space of the gallery, while Reisinger inserts the physical object in a digital landscape and Hardcastle moves back and forth between the two planes, as an exploration of their mutual influences and tensions. In all three cases, a return to the physical object and to craftsmanship is important. Instagram is a channel to exhibit their exploration along the reality-virtuality continuum and showcase their creations. There are other artists, however, whose intention is to address more directly the role of the platform in the configuration of our consumer habits, and thus they end up sabotaging the platforms from the inside.

- Flouting the platform’s veracity principle

One technique to do so is to ironically reproduce the platforms’ aestheticized content. As Boris Groys has observed:

Today, everyone is subjected to an aesthetic evaluation—everyone is required to take aesthetic responsibility for his or her appearance in the world, for his or her self-design. Where it was once a privilege and a burden for the chosen few, in our time self-design has come to be the mass cultural practice par excellence.

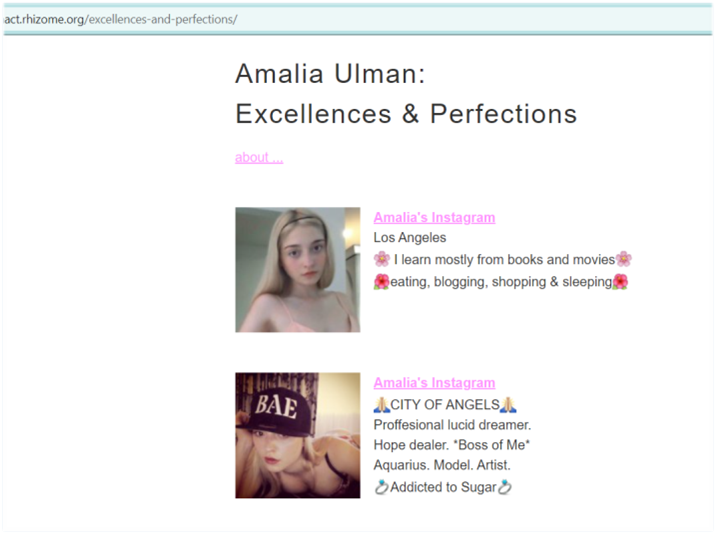

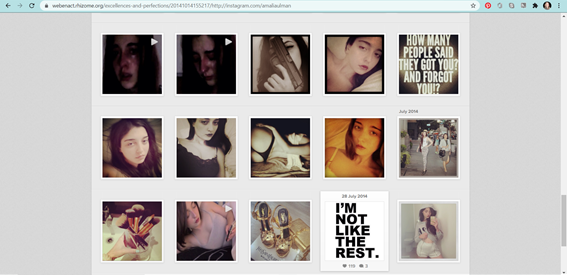

Amalia Ulman (Argentina, 1989) has used Instagram to both construct her work and expose the toxic nature of its own framework. The general theme of her net art is the way in which relationships are built from appearances, which she has exploited by creating her own fictional narratives around identity construction in Instagram. Her most celebrated project to date is Excellences and Perfections, which flouts flagrantly the already weakened veracity principle attributed to online profiles (Fig.8-10). During six months of 2014, Ulman built a story of an extreme make-over through Instagram posts that were not her own, even though she signed them with her name (confusing friends and acquaintances alike). It recounted the experiences of a girl in her twenties looking for success in the city of Los Angeles. From the apparently idyllic life of a naïve girl to the struggles of the sexy vamp, she goes through break-up with her boyfriend, injects Botox, falls into drugs, undergoes cosmetic surgery for breast augmentation, suffers a nervous breakdown and, after hitting rock bottom, resurfaces. She built a complete story made with hashtags and in the image and likeness of the profiles of many girls her age that she found on the social network.

Amalia Ulman, like Intimidad Romero, plays with identity construction in social networks, blurring the boundaries between lived reality, masquerade, and pastiche. Their work is prototypically a post-internet product born out of excessive exposition to internet images. They denounce how the networks have enslaved us into living for them exposing more and more of our post-produced “real” life, instead of facilitating the promised liquid identity that would allow you to be whoever you desired, at least online. In the case of Intimidad Romero (her artistic name and that of her Facebook project), the pixilation and thus self-censure to which she subjected her own images (Fig. 11), provoked Facebook to close her account.

In both cases, what is subversive is that the real identity of the artist remains elusive, either by faking a banal yet popular ego or by self-censuring it before the platform has a chance to do it, thus the artist invents new norms for the algorithm to deal with. These works can also serve as tiny “inoculations”, as Eric Dean Rasmussen might call them, that might help developing an immunity to fake news through “the deliberate, mindful consumption of fabrications, fantasies, fictions, hoaxes, and nonsense–in short, literature” (Post-Digital , 276).

- Implausible exhibits and data collection

Joshua Citarella’s work, Compression Artifacts (2013), also belongs to this second stage in the relationship between art and the digital sphere initiated by the web 2.0 and its new forms of participation. In this case, Citarella addresses the dominance of the digital networks as new exhibition spaces (even before the Covid pandemic) and plays with the array of possible mediations between physical and virtual representations.

For this piece, Citarella has constructed in a secret location what appears to be an exhibition space. There is no way any spectator can reach it physically since we have not been informed of its existence prior to its deconstruction. The construction was performed in front of a live feed, broadcast during daylight hours. The process was thus recorded, and then postproduced to augment its size or to decrease it at will, its objects also dematerialized by fire. Eventually everything is brought to its ashes. What remains is the process as recorded in videos and photographs disseminated in the networks.

As in Almudena Lobera’s “Stories”, in this piece we find an exhibition inside another, but what is at stake really in this performative, procedural work, is its implicit commentary on the importance granted to the exhibition space, the container, and conversely the art objects that comprise the installation become banal. Again, it is the context, the background, which is laid bare and questioned.

Conclusion

Artists’ use of Instagram and other platforms is twofold: at once it benefits from their dissemination potential, as it also poses a critical stance regarding their algorithms’ logic. They are aware of the commercial objectives of the platforms and try to skew or appropriate them, depending on their own intentions. But as Kenneth Goldsmith has also observed: “While we play the Instagram game by liking and reposting photos, the apparatus knows otherwise: a like is a way for the shareholder to verify that there are consumers populating the program” (144).

For Spanish critic Juan Martín Prada, the immateriality of the net art work was a problem for its commercialization and post-internet art implies a return to the object, not only to make a clearest statement (as Arcangel defends) but to be able to sell it. Nowadays, we could say, following Latour, that we were never modern, not even postmodern, since we have managed to commercialize virtual objects by making them scarce, unique, once again. Through blockchain technology, the non-fungible tokens (NFT) have returned if not the aura to the work of art, at least its monetary value.

Post-internet artists differ from many electronic literature artists in the way they have been able to exploit the platforms to make their work well-known and sellable. However, in the same way that Marisa Olson identified post-internet art as a type of production that was not strictly computer/internet based but that it was in some way influenced by the internet and digital media, post-digital electronic literature is also experiencing this overture towards other works that might not be strictly classified as electronic literature but spring from a similar experimentation with platforms and artistic creation, traversed by or going through computer programs and machinic spaces, and reaching out to find new audiences. As close relatives in the artistic field, we have identified the same impulses in post-digital electronic literature as we have perceived in the artists discussed in this essay: a nostalgic mixture of analogic and digital techniques, a renewed interest in technological obsolescence and sustainability, and an inquiring attitude towards an ever-expanding technological mediation.

It is now time to evaluate if artists can use the master’s tools to dismantle the master’s house, if these post-digital and post-internet pieces can expose something we were not aware of in our new ways of relating to art and to one another. Though it is difficult to demarcate these categories, we observe that we can identify two trends along the commercial or critical positioning of the authors, though many will mix these trends in their works. We often refer to post-internet art as an art of conspicuous consumption in which the self-aware internet user makes post-internet art as a prosumer every time he/she visits these installations and participates in the performance, as in Lobera’s Stories. We would like to associate post-digital art with those works that focus on the transcendence of the medium by recontextualizing, recuperating, reusing ad infinitum, fragments of old and new media, calling for the need to find an equilibrium between the different spaces we inhabit, virtual and real, identifying the particular qualities, textures, structures, in each of the manifold layers of reality we move about.

But what happens when digital technology is capable of reproducing to perfection the qualities of the physical medium, does the traditional association and classification of art objects with their medium disappear? In never-ending cycles of appropriation and re-appropriation, production and digital post-production, inscription and re-inscription, contextualization and recontextualization, mediation and remediation, where does one locate the importance of the medium? Or, should we conclude, as Spanish critic Germán Sierra believes, that in post-digital art the medium is destroyed with the message?

Maybe “destroyed” is excessive, but certainly in post-digital art the medium is problematized, strained, its limits exposed. However, we do not seem to have moved beyond the need of self-referencing the medium constantly, as all nascent media do ‒and as we know electronic literature has done for a long time‒, since new combinations of mixed reality become possible every day, continuously expanding our horizon of expectations. What is certain is that the aesthetic experience has been forever altered by the platforms’ modes of consumption and production, veering audiences to a perpetual state of distraction rather than contemplation.

As a way to counteract this distraction, we can expect that inserting aesthetic practices in the platforms’ milieu becomes a tactic, not only for inoculating the viewer against more harmful content, but also, as we have seen with Arcangel’s Super Mario Clouds, as a way of shifting our perceptual habits and pace, since, as Rasmussen has observed, “[a]ltering the rhythms at which we normally think and feel allows for a narrowing of focus, an intensification of awareness, and somewhat curiously, a modicum of critical distance” (284). Let us be optimistic.

Works Cited:

Casone, Kim. “The Aesthetics of Failure: ‘Post-Digital’ Tendencies in Contemporary

Computer Music”, _Computer Music Journal, 24, 4 (Winter, 2000), Cambridge, MIT Press, pp. 12-18.

Cramer, Florian. “What is ‘Post-digital’?” APRJA, 3, Issue 1, 2014.

Dafoe, Taylor. “Cory Arcangel’s Latest Artwork Is a Kim Kardashian-Themed Video

Game. What Does It Mean? Don’t Ask Him”, Artnet, April 9, 2021, (accessed

1/2/21). https://news.artnet.com/art-world/cory-arcangel-interview-1957736

Droitcour, Brian. “Why I hate post-internet art”, (accessed 1/2/21).

https://culturetwo.wordpress.com/2014/03/31/why-i-hate-post-internet-art/

Fernández Porta, Eloy. Nomography. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2021._

Fletcher, Robert P. “Digital Ekphrasis and the Uncanny: Toward a Poetics of Augmented Reality”, Post-Digital: Dialogues and Debates from electronic book review, vol. 2. Great Britain: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020, pp. 303-318.

Goldsmith, Kenneth. Wasting time on the internet, Harper Perennial, 2016.

Greene Naftali Gallery. Cory Arcangel, Century 21, exhibition leaflet, (accessed 1/2/21). https://greenenaftaligallery-viewingroom.exhibit-e.art/viewing-room/cory-arcangel#tab:thumbnails

Groys, Boris. “Self-Design and Aesthetic Responsibility,” E-Flux Journal, no. 7 (June-August, 2009), (accessed 1/2/21). http://www.e-flux.com/journal/07/61386/self-design-and-aesthetic-responsibility/

Lindhé, Cecilia. “‘A Visual Sense Is Born in the Fingertips’: Towards a Digital

Ekphrasis.” _DHQ: Digital Humanities Quarterly, 7, no. 1 (2013), (accessed 1/1/22). http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/7/1/000161/000161.html

Martín Prada, Juan. Martín Prada, Juan. “Sobre el arte ‘post-Internet’”, 15 June, 2020. In Teorías estéticas contemporáneas, (accessed 1/2/21). https://teorias-esteticas-

Milgram, Paul; H. Takemura; A. Utsumi; F. Kishino (1994). “Augmented Reality: A class of displays on the reality-virtuality continuum”. Proceedings of Telemanipulator and Telepresence Technologies, pp. 2351–34.

Olson, Marisa. “PostInternet: Art After the Internet”. Foam Magazine 29, Winter 2011, pp. 59-63; repr. in Art and the Internet, London: Black Dog, 2013.

Rasmussen, Eric Dean. “Literary Ecology: From Resistance to Resilience”, Post-Digital: Dialogues and Debates from electronic book review, vol. 1. Great Britain: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020, pp. 273-291.

Schnabel, Marc Aurel. “Framing Mixed Realities”, in Wang, Xiangyu and Marc Aurel

Schnabel (eds.), Mixed Reality in Architecture, Design & Construction, Springer, 2009, p.4.

Sierra, Germán. “Una década de creación postdigital”: Comunicación de Germán Sierra en la Jornada “Postdigital: ¿un término para el ahora?”, in Rec-Lit, 22 Sept. 2020, (accessed 1/2/21). https://reclit.hypotheses.org/14

Tabbi, Joseph. “Recollection in Process”, Post-Digital: Dialogues and Debates from electronic book review, vol. 1. Great Britain: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020, pp. 3-9.

Cite this article

Goicoechea, María de Jorge. "The Art Object in a Post-Digital World: Some Artistic Tendencies in the Use of Instagram" Electronic Book Review, 6 February 2022, https://doi.org/10.7273/kvq8-h368