The Metainterface of the Clouds

The following assemblage, one of a series initiated with ebr version 7.0, is composed of four elements: a presentation (for release in October 2018) of Søren Bro Pold & Christian Ulrik Andersen’s The Metainterface including an excerpt from “The Cloud Interface: Experiences of a Metainterface World” chapter of the book (with permission from The MIT Press); a discussion (November 2018) by Scott Rettberg and Roderick Coover about the visual and narrative design of Toxi•City: a Climate Change Narrative, and a discussion of issues raised by The Metainterface (December 2018) that were taken up by the Bergen Electronic Literature Research Group during the EcoDH seminar, University of Bergen, June 14, 2018, and an interview with Shelley Jackson (January 2019) focused on her project Snow and her new novel, Riddance; or, The Sybil Joines Vocational School for Ghost Speakers & Hearing-Mouth Children. Contributors: Christian Ulrik Andersen, Roderick Coover, Shelley Jackson, Elisabeth Nesheim, Scott Rettberg, and Lisa Swanstrom.

This essay is published as the first in a series of texts centered around the publication of The Metainterface by Søren Pold and Christian Ulrik Andersen. Other essays in the series include: Always Inside, Always Enfolded into The Metainterface: A Roundtable Discussion., Voices from Troubled Shores: Toxi•City: a Climate Change Narrative and Room for So Much World: A Conversation with Shelley Jackson.

For a number of years, we have worked with the concept of the interface. What does this mean, and how does it relate to literature and landscapes? We’ll try to give the semi-long answer through this paper, but here’s a shorter statement to begin with: Firstly, the interface can be described as a special kind of sign, or to be more precise the interface is defined as the combination of signs and signals, of the mediated and the functional or of semiotics and material.⏴Marginnote gloss1⏴Forthcoming gatherings include a reprint of Sean Braune’s

Phorontology (Punctum 2017) with serial commentary by Jhave Johnston*;* a gathering on Natural Media co-organized by ebr co-editors Lisa Swanstrom and Eric Rasmussen*;* and a November 2018 conversation, also in development at Bergen, on the work of Karl Knausgaard.

— ebr Editor (Oct 2018) ↩

The interface is our take on digital culture and how it constantly combines signs and signals in new ways and we believe it’s a good way of understanding and reflecting on computation. In our understanding, computers and computation are systems of interfaces between hardware, software and humans. Each interface is an abstraction in the ‘mise en abîme’ architecture of the computer where interfaces are layered between interfaces. Behind each level of the interface hides another level. All interfaces are operational dimensions that allow to combine instrument and media and no interface such as for example the code, the API or the user-interface is more essential than others. In this way, interfaces are neither non-representational nor fully contained by representation, they function by how they make relations between materiality and sign-processes. They are neither non-human nor defined within classical humanism, neither just out there, externally, nor simply a perspective. Rather current interfaces work by how the material environment is rendered semiotic and computational and simultaneously how the environmental becomes computational.

This paper is part of a larger book project, conceptualizing current developments of the interface, of which climate problems relates. The book is called The Metainterface – The Art of Platforms, Cities and Clouds, recently published by The MIT Press with a front cover made by the Spanish artist, César Escudero Andaluz, based in Linz, Austria as part of the Interface Culture program at Kunstuniversität Linz. The metainterface describes the current interface that has moved from a confined system between a user and the computer to a general and global-scale virtualization. In this sense the metainterface’s problems are also global and have moved from problems of usability to the level of general elections, climate change and war on terror. For us the metainterface is a concept that describes a contemporary interface paradigm and how the interface seems to evade perception, and become global (an abstract spatiality, everywhere, or “in the cloud”) and generalized (in everything – sealed off in any thing we may encounter). Simultaneously, the metainterface is an industry. This new interface-industry allegedly produces a new reality of smooth access to the streaming of media, and smart profiling of consumer needs—we know this from Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple and Spotify. Thirdly it is a practice, an art and a way of living that might point to alternative ways of construction and design.

Our book follows the metainterface through the art of platforms, such as smartphones, tablets, e-readers and other devices which we see as new platforms for culture or what we define as a metainterface industry, through the territorial interfaces of the urban metainterface, and further through to the cloud interface and how it relates to experiences of a metainterface world and its global crises of climate change and wars on terrorism. Finally, we ask how to perform a criticism through design, which includes the digital literary exhibition The Poetry Machine/Ink. Our book is composed of analytic discussions of digital art, including software art, Net Art, apps, installations, activism and electronic literature, in order to suggest how art explores this technological change of the new metainterface.

With current metainterfaces in mind, we could say, that the interface is increasingly topographical. Territorial interfaces such as smart cities and global clouds are topographical in the way they both present and produce contemporary environments. They are inherently folded into the environment and in this way actively interfacing. We both sense and produce the environment through interfaces and interfacing. A good example of this is the climate crisis. Despite the fact, that we can begin to experience it directly through strange weather phenomena, climate change is still mainly an abstract problem calculated through cloud-based, global computing networks. Epistemologically speaking, the climate crisis introduces the situation that the perception of even immediate surroundings is now influenced and mediated by complex visualizations, statistics and carbon quotas. In other words, an interface of climate data and carbon outlets lurks in the blue sky of the current weather. Which doesn’t mean in any sense, that climate change is not real, rather that it is a symptom of the fact, that our reality - and how we access it - have changed.

The blue sky has become clouded in more than one way. The cloud interface is an abstraction and generalisation of computing. We increasingly don’t know where either our data or the software is located; what either is doing becomes increasingly opaque and interfaces become abstract as either closed devices (metainterface platforms) or ubiquitous services like Google. Tung-Hui Hu characterises the cloud as an example of virtualization and layered abstraction, “a way of turning millions of computers and networks into a single, extremely abstract idea: ‘the cloud’.” This also influences the perception of the interface and how it becomes environmental. As J. W. Morris writes cloud based services such as music “comes from everywhere and nowhere” and are “posing” as a quality of the environment.”

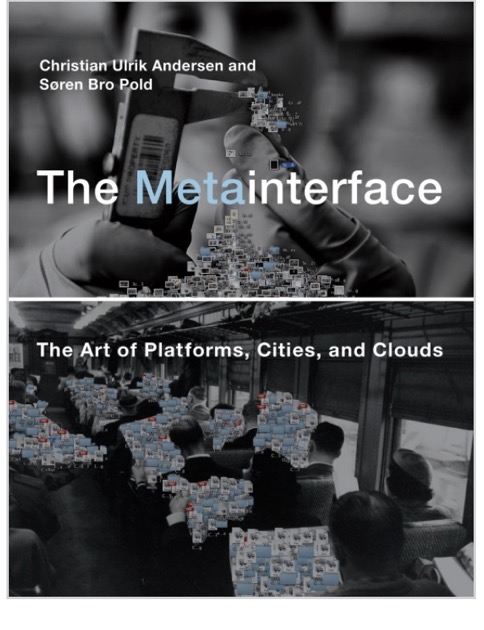

The cloud can be described as a phantasmagoria of globalization – something that hides its material effects and labour behind e.g. a Dropbox folder or a Google search, and this cloud phantasmagoria displaces social, political, ecological and territorial conflicts. When you interface with fx Google services on your smartphone, the Catalan artist Joana Moll’s CO2GLE demonstrates that what you see is clouded and what you get is displaced and concealed by the phantasmagoria of the cloud, that hides the environmental effect of Google searches.

Consequently, there are parallels in the way that climate change and cloud computing is constructed and perceived as abstraction, alienation, virtualisation and globalisation. If cloud computing is globalisation in our pockets, climate change is globalisation in our environment – or at least an effect of this. However, cloud computing is not only part of the problem, but also part of perceiving the problem. Cloud computing gives us a vision of the planet from above and afar, it gives a collective possibility and responsibility for social and political action. Viewed from above and afar, the climate – as the constant interactions of humans and non-human actors in a system – may potentially become present and vernacular. However, living in the climate crisis, the call for uncompelled action is not self-evident. “What can you do?” and “how can you see it” seem to be the proliferated questions.

Climate interfaces:Toxi•City

Roderick Coover and Scott Rettberg have explored this aspect of the climate crisis in their recombinatory film Toxi•City: a Climate Change Narrative . The film portrays people living in a river estuary after the climate crisis has struck with repeated storms and floods. It takes place in a near future in the post-industrial Delaware River estuary, which is home to several large oil refineries and a nuclear power-plant and located near large cities like Philadelphia and the coastal shores of New Jersey. The work is usually displayed as an installation in a dark room, on a large 5:1 cinemascope widescreen. The images are of the Delaware River, its waters, ships, shores and industrial architecture. The wide panoramic format, with rarely any humans in the picture, emphasizes the power of a nature out of balance. This impression is sustained by often low-key colours, semi-transparent impositions of for example ships and water, and slow camera pans that emulate the river’s floating (Watch video: BeginB.mp4). The imagery has its own beauty in spite of the post-industrial decay, equaling what in the German Ruhr district has been called ‘industrial nature’.

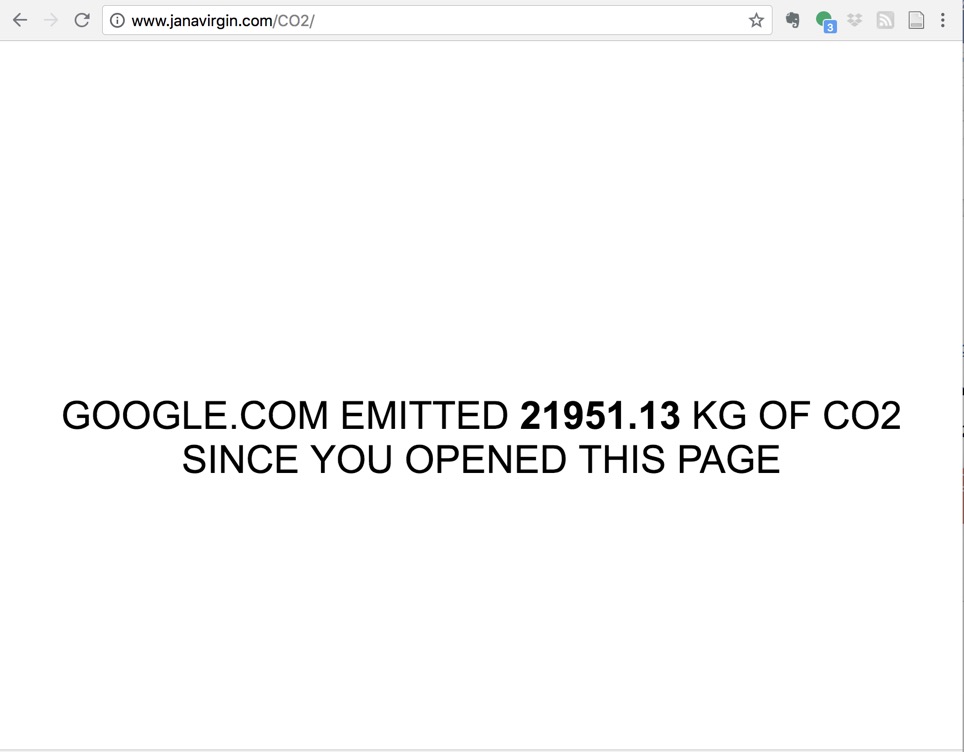

Toxi•City’s narrative combines fictional testimonies about how to survive in this post-catastrophic environment with accounts of actual deaths caused by potential climate-change related storms and floods, such as the 2012 Hurricane Sandy. The film has four beginnings, 38 episodic narratives told by its six protagonists, 32 nonfiction stories of deaths from actual storms, five segues showing the urban and river landscape, and the ending. The episodic narratives play in semi-random order; only intervened by the factual death stories and segues.1 The beginnings anchor the stories in the post-catastrophic estuary landscape, and its many episodes introduce the daily struggles of the six main protagonists at a place where disastrous recurring floods and storms – and the pollution, shipwrecks and faulty rescue operations that follow from them – have become a condition for living.

The mixture of nonfiction death stories, the actual setting and the fictive near-future stories on how to survive and adapt, creates a topographic narrative of a drowned, polluted and diseased landscape where people struggle to get on, and to understand what they are exposed to. For instance, a pig farmer suggestively asks if all the warnings from “tree-huggers and democrats and Hare Krishna and so-called scientists” made “us one bit more prepared?” (Watch video: CM_3A.mov). He seems to be the only character who somewhat succeeds in this tough environment; as he says in typical free market thinking, “Show me a crisis and I’ll show you an opportunity.” The other protagonists are mostly victims of their helplessness and are seeking signs in nature. Even the beautiful sunsets are a cause of anxiety for the young woman, when she realizes that their many different hues that she enjoys so much, are probably due to pollution. Still she finds them “kind of magical” and settles into resignation: “Life is hard but I think it is sort of our job to live in the moments that we have now” (Watch video: YW_3B.mov). Though the protagonists strive to understand the situation, their potential possibilities for taking action suffer. It is a desolate story about the loss of lives and nature, and the intervening death stories are like the chorus in a Greek tragedy. However, there are also scattered moments of connection and humanity, including the final episode where the young woman sees the teenage boy digging a grave for his mother and it ends: “I walk towards him. I know what he is doing. I can help him with this task.”

But how does Toxi•City relate to the alienation and abstraction of the metainterface and the cloud? We argue that it does this through the combination of 1) its recombinatory narrational structure and 2) through its panoramic visuality.

The feeling of human powerlessness is emphasized by the poetics of the recombinatory database narrative. Instead of being sequential, the narrative is a paradigmatic landscape of voices without apparent order, besides the fact that they live in the estuary and are victims of its ecological breakdown. The narrative cause and effect that is usually delivered by an explanatory human narrator, is in Toxi•City, as argued above, replaced with an algorithmic narrative mechanism, where there seems to be no traditional, narrational order, apart from the ordering of beginnings, character narratives, death-stories and segues. The random conditions of the machine and its un-intelligent, combinatory algorithm reflect the desolate fate of the protagonists in an ecology whose balance has been profoundly disturbed by humans, to the extent that they literally drown in their own toxic remains: it is a post-human narrative told by a post-human machine.

The post-human narrative of how we struggle to interpret, act upon and even survive within a climate crisis is also a story of how to narrate this crisis. The characters are generally not able to get a general perspective but instead are enclosed by the crisis environment and adapt their modest strategies trying to survive and make sense. However, Toxi•City’s own algorithmic poetics and its panoramic-cinematographic visual aesthetics, work as a way of telling and sensing the climate crisis. This creates a tension between the helpless individual destinies of the estuary on the one hand, and the aesthetic and poetic qualities of the artwork on the other. Perhaps it could be characterized as an Anthropocene panorama, a blues on the climate crisis that depicts the catastrophes and sorrow, but also allows the viewer to indulge in it, to feel the pain and basically to be engaged, at least aesthetically, and in this way, gradually explore what a panorama of climate change could look like.

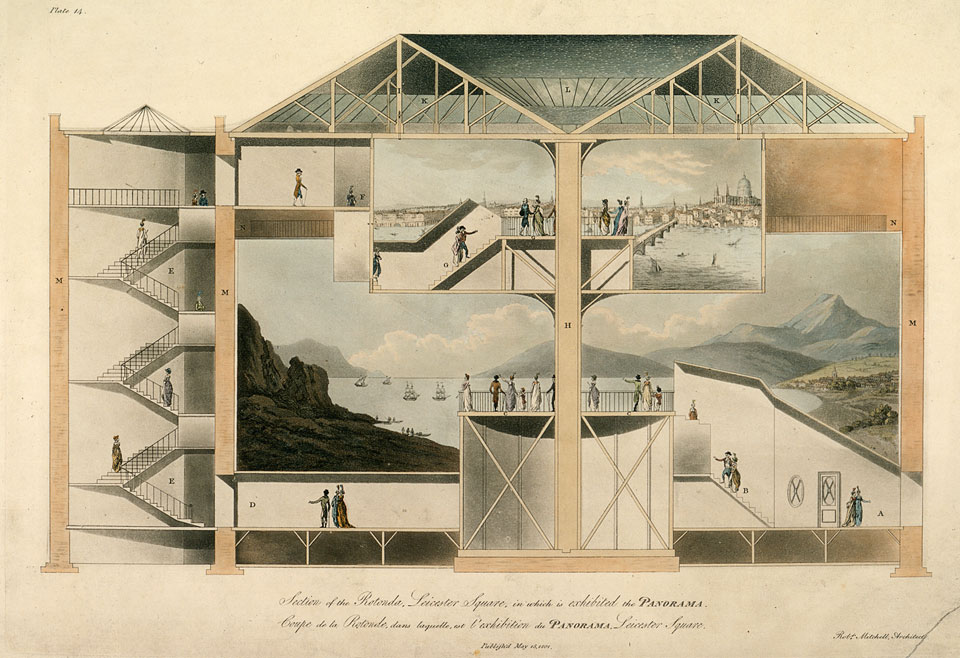

Panorama literally means “all seeing,” and as the first visual mass medium it became popular in the nineteenth century as a phantasmagorical architectural medium in which the mastery of the modern bourgeois perspective of control and commercialization is both learnt and glorified (Oettermann, 1997).

In Coover and Rettberg’s work, it becomes a way of experiencing what the characters in Toxi•City cannot quite see. It is a climate change panorama that demonstrates how nature and the environment are controlling the characters, by being out of control. As Coover writes: “The Panorama offers the viewers an illusion of commanding a total view of a moment; actually, it is the image that encompasses the viewer in the exotic locales of its form.”

In this way, Toxi•City can be understood as a continuation of Walter Benjamin’s efforts to “reconceptualize experience through the very conditions of its impossibility,” as Miriam Hansen expresses it. As a panorama, Toxi•City demonstrates the limits of human perception: the circumstance, as also experienced by the narrators, that climate change cannot be seen clearly. But it does so as an all-seeing technological, narrative spectacle: a panorama that depicts the human imprints on a geological scale. In this panorama, the spectator loses control of the image. It is a panoramic illusion of total overview where the image encompasses the spectator.

Toxi•City shows both that we cannot see, and what we cannot see: the climate is clouded, displaced, both everywhere and somewhere else. The possible spaces for seeing and taking action are limited, but Toxi•City’s panorama, the technical mediation of climate change, presents itself as an opening – or, rather, as a way to, reflect a ‘clouded perception’ of reality. Through its algorithmic narrative structure and its Anthropocene panorama, it demonstrates a vision of sense-perception in the age of clouds and climate change.

Weather interfaces: Snow

As Toxi•City exemplifies, the human imprint on the planet alters perception: it makes perception work on a different scale. Imprints of consumption and production may be seen in smog and other kinds of pollution on a local scale, but they are often not perceivable. They work on a different scale, where causes and effects are not seen in the everyday but instead on the level of the planet’s geologic eras. Seeing the environmental conditions in the everyday is hence simultaneously an experience of losing sight. A call for action may be directed toward the environmental activist, but it is equally important to reflect how reality is produced on the level of perception. If Toxi•City speculates on how one may live with this change of perception in a time where climate changes are beginning to have direct impact on the everyday, Shelley Jackson’s Snow asks to the perceived nature of imprints and the inscriptions themselves in a time of metainterfaces and cloud computing.

Shelley Jackson began publishing Snow in January 2014 (and the work is still under publication). It is published sequentially as images of words written in snow that are distributed on Instagram and Flickr, and since every image only contains one single handwritten word, it both requires quite some work and snow on the ground in Jackson’s hometown Brooklyn in order to be written and published.

Snow’s content is a phenomenology of snow in its many different kinds, how it surfaces the world, and even records and explores the world: “There are depraved snows that make unwelcome advances and cerebral snows that sifting along surfaces seek knowledge of the countless forms of the world.”Snow becomes a writing surface, a kind of paper. Or rather, paper, the snow on the ground, and potentially many other surfaces, appear as spaces that can be inscribed with signs. Snow expresses a fundamental relationship between writing and urban spaces, and naturally also relate to a history of land art (Nacher, 2017). However, in contrast to writing in stone, or even writing on paper, writing in snow is profoundly ephemeral. Or rather, it speeds up the ephemerality of inscriptions that is also present in other materials like tattoos, which Jackson has used in her other piece Skin, and in writings on paper. But like architecture, it is also immobile and related to local context. Reading the text, one literally reads not only about snow, but also the different kinds of snow and locations that are displayed on the images (slush, frost, snow on streets, snow on objects, etc.).

In these ways, Snow shows a world with ephemeral inscriptions in a highly local context. To reproduce Snow, will inevitablyabstract the text from its contextual element. Hence, the proliferation of the work on Flickr and Instagram produces a paradox. Though the text is readable through images on Flickr and Instagram, it is also a text that is meant to be imagined. The reading experience is in other words also an experience of a dislocated writing. The global accessibility of Instagram and Flickr is at odds with the ephemeral quality and site specificity of the snow in Brooklyn; and reading the text on social media almost feels like a violation of the writing, like abstracting superficial data from the body of the world. Consequently, Snow explores and reflects the underlying crises of representation and mediation in the frictions between the local, materially contextual, ephemeral on the one side, and the global, networked accessibility on the other. It is, in short, not just a work in snow, but also a work that displays the frictions between the site-specific text and the distributed photos and text on social media.

Yet, the letters inscribed on the white surface of the snow bear more than a metaphorical relation to the printed letters on paper, and the crisis of representation that it expresses is much more than a mere dislocation of writing from paper to the clouds and metainterfaces of social media. Snow is a “story in progress, weather permitting,” as it is stated on the project’s Instagram account. In other words, it relates the material inscriptions of the story to not only social media, but also to the weather. Snow, along with other weather phenomena, like wind, temperature, humidity, and also clouds, are all signs of the climate. The changing shapes of clouds, increasing winds, decreasing temperatures, droughts, floods, etc. are hence signs of potential changes in the climate; changes that one easily loses sight off, as demonstrated in Toxi•City.

Cloud metainterface

As Snow and Toxi•City indicate, climate change has added a new semiotic layer to the experience of the weather and the surroundings. The weather is not only a conversation starter, or a forecast that can be used to take precautions for how to dress, when to seed, routes to navigate on the ocean, etc. The weather is extended from a local scale to a global scale of the Earth and its geological eras. The weather is, in other words, not something simply ‘out there’, but has become an interface of contingency: not true, not false, but a potential sign of climate change and ecological catastrophe. When the signs of climate change are observable as melting ice, floods, droughts, fires and other changes in weather across the globe, global measurements and future models also become the foundation of discourse: the reality of the metainterface becomes a concern.

For instance, in Snow, the lack of snow is a persistent underlying theme. The work unfolds over years, and as a reader, one constantly reflects on its presence as a sign of much larger weather systems. Is the presence of a snowstorm or unusual warm weather and lack of snow in the winter a sign of global warming? Such questions are intrinsic to the reading of Snow, so diligently dependent on the weather. In this way Snow is a work about not only snow, but also the epistemology of climate change—about how we perceive (the lack or excess of) snow in the urban environment as an emerging global concern that is spread across networks. The reader not only reads the meaning of the words, but also the writing of climate change in the local weather, on the surface of streets, or the melting ice on the lake. Snow seems to suggest that the writing of climate change is as frail and insubstantial as melting snow on an urban pavement—something that slightly disrupts and slows traffic, but is soon cleared for efficiency. Climate change is staged as a writing that is important to read before the moment of reading is gone, and it is too late. In this sense, through its ephemeral and dislocated writing, Snow points to alternative interfaces for cloud computing.

To conclude, Toxi•City and Snow both relate to the topography of the metainterface—with the cloud the interface seems to evade perception, and become global (an abstract spatiality, everywhere, or “in the cloud”) and generalized (in everything—sealed off in any thing we may encounter). These works also point out how great art and literature can explore technological tendencies through their own technological aesthetics and sense perception. They don’t just show a world under climate crisis, but also explore how we can and cannot see this world, and under which technological conditions it is produced and presented. It is a kind of realism that explores its own conditions, its own sensorium or metainterface. In this way, they also point out, how the metainterface is territorial and topographical. In order to discuss this and design different topographies, we need to explore and create interfaces that are more open about their environmental effects. Perhaps the clouded sense-perception of Toxi•City and the localized and ephemeral character of Snow points to this, we just need to read the writing before it melts.

References

Benjamin, Walter. “The Author as Producer.” In Selected Writings, edited by Michael William Jennings, Howard Eiland, and Gary Smith, 2:768–782. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1996.

Coover, Roderick. “The Digital Panorama and Cinemascapes.” In Switching Codes; Thinking through Digital Technologies in the Humanities and Arts, edited by Thomas Bartscherer and Roderick Coover 199-217. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011.

Coover, Roderick, and Scott Rettberg. Toxi•City: A Climate Change Narrative. 2014, 2017. http://crchange.net/toxicity. CR Change Production.

Hansen, Miriam Bratu. “Benjamin’s Aura.” Critical Inquiry 34, no. 2 (2008), http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/529060, 336-75.

Hu, Tung-Hui. A Prehistory of the Cloud. Cambridge, Massachusetts & London, England: The MIT Press, 2015.

Jackson, Shelley, Snow - a Story in Progress, Weather Permitting. 2014-. https://www.instagram.com/snowshelleyjackson/ and http://www.flickr.com/photos/25935290@N04/sets/72157639539497175, 2014-.

Morris, Jeremy. “Sounds in the Cloud: Cloud Computing and the Digital Music Commodity.” First Monday 16, no. 5 (2011), http://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/3391/2917.

Moll, Joana. CO2GLE. 2016. http://www.janavirgin.com/CO2/.

Munn, Luke. “Rendered Inoperable: Uber and the Collapse of Algorithmic Power” A Peer-Reviewed Journal About 7, no 2, 2018. http://www.aprja.net/rendered-inoperable-uber-and-the-collapse-of-algorithmic-power/

Nacher, Anna. “The Creative Process as a ‘Dance of Agency’: Shelley Jackson’s Snow: Performing Literary Text with Elements.” In Digital Media and Textuality: From Creation to Archiving, edited by Daniela Côrtes Maduro. Media Upheavals 45. Bliefeld: Transcript Verlag, 2017.

Oettermann, Stephan. The Panorama : History of a Mass Medium. New York: Zone Books, 1997.

Footnotes

-

The running of Toxi•City is controlled by a JavaScript which in the 2016 version explored here runs 3 (out of 4) beginnings. The main part is a series of narratives consisting of an a-narrative, a b-narrative (there are 19 of each) followed by a chorus/death story, and after every five of these series one of the segues is played. After 16 series the ending is finally played. All film sequences are chosen randomly following these rules and it is made sure that no sequence is repeated within a session, and some sequences are left out ensuring that similar sessions will rarely occur. After the session, which lasts approximately 40 minutes, the script reloads and restarts. The characters are described in the accompanying description and consists of a fisherman, a young woman, a FEMA relief worker (FEMA is the US Federal Emergency Management Agency), a middle-aged woman, a pig farmer and a teenage boy. Roderick Coover and Scott Rettberg, Toxi•City: a Climate Change Narrative*.*CR-Change Production. ↩

Cite this article

Pold, Søren Bro and Christian Ulrik Andersen. "The Metainterface of the Clouds" Electronic Book Review, 6 October 2018, https://electronicbookreview.com/publications/the-metainterface-of-the-clouds/