2011

Too much about too little, and too little about too much. Reviewing the new critical collection Against the Grain: Reading Pynchon's Counternarratives, this critic finds evidence of overproduction in the "Pyndustry."

Literature joins the living dead. A critic illuminates Brian Lennon's "scene" of literature today: both suspended and emergent in the world system.

How does a sample of de Quincey's Confessions of an English Opium Eater give birth to a mutant, six-fingered hand? This essay articulates the logic of Noon's 2001 experiment in constrained writing, which concretizes the play of signal and noise, pattern and randomness, in the flow of information. In the process, the critic suggests, Noon dramatizes how printed texts rupture and reassemble when they are transferred to electronic media.

Richard Kalich's latest protagonist is Richard Kalich, but one critic views this postmodern occupation of the novel as an opportunity - even an encouragement - to forget about him.

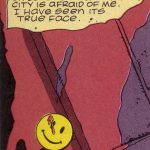

Engaged in his own kind of structured play, Stuart Moulthrop uses the concept of "under-language" to explore the boundaries, gutters, masked intentions, and hidden meanings of Moore and Gibbons' Watchmen, while simultaneously using the graphic novel to provide an equally complex, over-determined rendering of the term.

Gregg Biglieri offers some advice on reading McElroy: jettison one's habitual grammars and adopt the grammars of time and timing. Become an expert in sound. Become all ear.

Citing the narrator's radical ambivalence about time, history, and the flesh, Maureen Curtin argues that American Genius, A Comedy represents the hysteria of the contemporary "post-political" moment.

Contrasting Lynne Tillman's text with the "complicitous critique" of Donald Barthelme and other postmodern ironists, Sue-Im Lee argues that Tillman's narration displays the "mobility" of Adornian cultural criticism, in which contradiction is not a problem but a mode of interrogating the present.

Most recent "Great American Novels" are not great, but merely big. Lynne Tillman's American Genius, A Comedy, by contrast, is designed with scale, not size, in mind. So argues Kasia Boddy, who reads the novel as a critical engagement with book reviewers' favorite cliché for ambitious social fiction. Instead of resisting cultural obsolescence through sheer assertion, Tillman's book examines how the cracks and contradictions of American ideology have imprinted themselves on the individual body, bearer of the national disease: sensitivity.

"Like skin, the comma both connects and divides." Peter Nicholls traces Tillman's endlessly subordinating, endlessly equivocating sentences, showing how their quest for historical and social clarity passes through an interminable sequence of deferral and denial.

How does one write science fiction when the atom bomb (and later 9/11) makes the future seem impossible to predict? Justin Roby reviews Paul Youngquist's Cyberfiction: After the Future, which explores how postwar "cy-fi" critiqued life in the age of cybernetic control systems.

Can the rising cost of cosmopolitan real estate have brought the New York City novel to a low point? Tom LeClair measures recent fictions from and about New York City - including three "9/11 novels" - against the Systems Novel of the mid-1970s.

Two innovative contemporary writers discuss the relationship between encyclopedic narrative and notions of gender and writing, the body as the physical embodiment of memory, and the unique syntax of Tillman's American Genius, A Comedy. The novel's prose depicts the way "thought, when you're not thinking, happens."

Anthony Warde traces Daniel Punday's analysis of the intertwining strands of contemporary "fictionality," the different modes - from "myth" to "assemblage" - by which invented stories are legitimated. Punday's work implies that the active construction of 'life-fictions' is becoming more significant in contemporary technoculture, a view that runs counter to the more pessimistic view of agency in Baudrillard's Simulacrum America and other accounts of a wholly 'virtual' reality.

David Shields is hungry, but not hungry enough. So says Curtis White, who argues that by ignoring anti-realism's past and present, Shields writes as if "New York" and "now" are the only contexts that matter.

In his introduction to the Cognitive Fictions cluster, Joseph Tabbi suggests that reflexive, non-narrative literature plays a critical role in the new media ecology. Postmodernist writing by Joseph McElroy and Italo Calvino, the posthumanist thought of Cary Wolfe, and the emerging forms of electronic literature each occupy a position between narrative modes of consciousness and "object-oriented" computer and cognitive science.

2010

Stephen Burn connects Don DeLillo's fifteenth novel, Point Omega, with the author's long-running investigation into the structures of the mind. Using an elusive narrative architecture, images from a slowed-down film, and moments of second- and third-order observation, the novel dramatizes the mind's pre-conscious fiction-making processes.

In this review-essay, James J. Pulizzi reads Joseph McElroy's 1977 novel, Plus, as a Bildungsroman for the posthuman: instead of tracing the development of a subject, the novel traces the development of processes that call the very idea of a subject into question. As a human brain adjusts to its new housing in an experimental satellite, the text unfolds in a series of re-entries and re-mappings, an unfolding that necessarily implicates the reader.

D. Fox Harrell considers how a media theory of the "phantasmal" - mental image and ideological construction - can be used to cover gaps within electronic literary practice and criticism. His perspective is shaped by cognitive semantics and the approach to meaning-making known as "conceptual blending theory."

Minds bind - make coherent meaning from distributed processes - and narratives do, too. The means by which they do so remains a mystery, however. Kiki Benzon suggests that this mystery is at the heart of Mark Z. Danielewski's House of Leaves, a text whose layered structure, typographical blending, and central metaphor - a house much bigger than the sum of its parts - enact the problem of binding on multiple levels.