On Digital Aesthetics: Sense-Data and Atmospheric Language

This article examines how the formation of data can be seen as an aesthetic way of making sense. Following work in digital aesthetics, the article proposes to understand digital artifacts and processes via formalization and operation of media language. Li traces this idea through several examples from recent literature, film, games, and artwork in South-East Asia. Together with these examples, Deleuze’s philosophical thoughts on a genesis of sense production are re-considered in order to understand a formal way of making sense in producing the new. The notion of “abstraction” from ancient Chinese mathematical thought offers a re-consideration of Deleuze’s “intensive virtual”, that is, the way the formal, the operative and abstraction determine the extensive intensive. Sense-Data and atmospheric language address computation’s materiality in engendering the formal and the operative modalities of media language, as a way of producing states of being and becoming in cultural activities in which the digital is an agency.

Media Language

In which way could the digital be understood as a creative force that engenders a lived experience of writing? The question suggests a way of exploring the digital in writing through a concern of its aesthetics, where aesthetics here means a creative engendering of the experience of being and becoming. The “digital” in recent literature of digital and computational aesthetics refers to the automation of the computational. As M. Beatrice Fazi and Matthew Fuller have indicated, computation “is a systemization of reality via discrete means such as numbers, digits, models, procedures, measures, representations, and highly condensed formalizations of relations between such things” (283). They address the materiality and medium specificity of computation. Relatedly, techno-aesthetics of algorithmic being-in-time by Wolfgang Ernst proposes a machinic view of understanding computation. The machinic is based on time-critical media and produces discrete states of being. The implementation of algorithm can make technically implicit knowledge explicit, and grant media operations an active epistemogenic agency (Ernst 16). This point can be seen as extending the medium specificity of computation into examination of its technological implementation and operative media. Following this line of thought, this article proposes to situate the examination of digital aesthetics in a material substrate of language. A materialistic view of language calls for a renewed materiality and mediality of computation following the above points. Media language in this article refers to a particular kind of material language that can shape data formation and make sense via its formalization and operation in the middle of other languages. This article would like to add to digital aesthetics that, the digital, characterized by its place value and abstraction based on mathematical extraction and computational algorithms, can also build a media language in the formation of data as an aesthetic way of making sense and producing the new.

Given this above proposition, this article has two aims. The first is to introduce sense-data, which addresses the place value and abstraction of the digital; the second is to articulate the sense-data in a media language called “atmospheric language”. The sense-data and atmospheric language together offer a new mediality and materiality based upon the medium specificity and technical milieu of computation. Before elaborating the notions of sense-data and atmospheric language, I hereby introduce the conditions of media language, which concern about why we need a media language to understand digital aesthetics.

My above proposition of a material substrate of media language is conditioned by an operative writing. Sybille Krämer sees writing as a cultural technique by addressing the operativity of writing. “Operativity” refers to an inter-spatiality in writing, which enables operations on syntax-visibility (“Writing, Notational Iconicity, Calculus: On Writing as a Cultural Technique” 524). Digitality for Krämer radicalizes what she called ‘artificial flatness’ with ubiquitous uses of interface, screen and smartphone (“From Dissemination to Digitality: How to Reflect on Media” 83). Writing in this cultural technique of flattening out however is paradoxically an inscription upon a surface in general, as well as an operative medium with its formalization. Krämer defines formalization as a combination of visual form with spatial positioning (“Mathematizing Power, Formalization, and the Diagrammatical Mind or: What Does ‘Computation’ Mean?” 348). Her definition of operative writing introduces the dimension of space into media operation. Further on, media language in this article is a constructive process that materializes data. Data is a part of notational materiality of media language. This notational materiality conditions a need to communicate with computation, its technical milieu, and cultural machines. With the notational materiality, data is understood via its positioning and place value in the operation and formalization of media language. The operation and formalization in turn organize material modalities of data.

Regarding the aesthetics of materializing data in media language, this article draws on aspects of Gilles Deleuze’s philosophy of difference, to elaborate what materiality we need and how media language operates and formalizes data. As Fazi argues, recent media studies give too much attention to the affective among medial flow, which follows Deleuze’s argument of the sensible in aithesis. She therefore calls for a materiality of computation that focuses on discreteness and procedural rules (15). In this article, a genesis of sense production by Deleuze is still useful to examine data and media language, because it offers a dynamic structure that allows the operation and formalization of media language to work in a material process. Specifically, Deleuze describes a linguistic paradigm with double causation: surface language refers to a quasi-causation while schizophrenic language relates to bodily causation (The Logic of Sense, 82-93). Being an inscription upon a surface as well as an operative medium, writing itself is a cultural technique in the technical milieu of computation. By technical milieu I attempt to address medium specificity of computation in its implementation of cultural techniques and technologies. This condition of technical milieu allows writing to be examined in a surface language as well as a bodily language. With this material substrate, a genesis of sense production in my point of view focuses on sense-events that express states of being and becoming via formalization and operation. This point of view also extends the machinic view of techno-aesthetics of algorithmic being-in-time by Ernst in that, formalization of media language can reveal the place value of the digital in its relationality and order of technical matter. Sense-Data in this technical milieu of computation therefore can be analyzed with atmospheric language, while atmospheric language in turn traverses among the material difference of sense-data.

The atmospheric of language in this article derives from elemental media studies. In elemental media studies, media is defined as relationality and order of things (Peters; Jue). Melody Jue proposes a milieu-specific analysis, addressing the nature of situated knowledge production for specific observer, that is, “in what environmental milieu do scholars write their theory, and to what extent does it inform their thinking and writing”(14). As Jue clarifies, milieu-specific analysis calls attention to the emergence of specific thought forms relating to “different environments”, which are significant for “how we form questions about the world, and how we imagine communication within it”(3). For media language, the atmospheric characterizes milieu specificity in the material difference of sense-data, like air traversing among its environmental materiality and being conditioned by its medial and technical milieu.

To exemplify sense-data and atmospheric language with a milieu-specific analysis, this article studies a series of cases. They are: the book project Object Speaking by a Shanghai-based graphic design collective RELATED DEPARTMENT and a poet Yongquan Mu, the short-story collection Rain by Taiwanese writer Kim Chew Ng, the moving image First Rain, Brise Soleil by Vietnam visual artist Thảo Nguyên Phan, the Japanese movie Drive my Car directed by Ryûsuke Hamaguchi, and the game Shu (Calligraphy) by a Chinese game developer Zitao Ye. Of these cases, the object book undergoes metamorphosis: it becomes and relates to a structural process (in Object Speaking), a formalization of painting (in Rain), a script language (in Drive my Car), even an operative concept (in Shu). The metamorphosis of book suggests different milieus in each case, showing material difference and elaborating how aspects of the theoretical framework of Deleuze’s genesis of sense production makes the conceptualization of sense-data and atmospheric language possible.

In the case of the book project Object Speaking by RELATED DEPARTMENT and Mu, sense-data work in a medium specificity of computation—the datafication of words in the search engine of second-hand trading platforms. It is data formation that reveals a rich notational materiality of the project, including names and sentences of hotel objects, translated keywords, text and image of selected second-hand items, all of which constitute the technical milieu of computation. Sense-Data positioned in this process shows that, the intensive and the extensive in Deleuze’s words are not reciprocally conditioned; intensity is qualified and quantified in extensities. This renews the relation between the intensive and the extensive, suggesting that a structural process of a book is a genesis of sense production, for the structural process of the book bears the notational materiality and makes different words, data, and signs operative, formulating atmospheric language.

Following the idea that the structural process of a book is a genesis of sense production, the article then mobilizes this idea into a wider media ecology, in order to illustrate how atmospheric language works within other languages in its material substrate. In this process, a dynamic structure as a genesis of sense production is developed. This process of sense production within dynamic structure is manifested in three cases that draw upon Deleuze’s concepts of series, structure, and minor language respectively. In the case of the short-story collection Rain by Ng, book contains a form of painting as manifest in the table of contents. This formalization separates series of short stories. The series in turn create tensions of forces and converge them into singular stories. The formalization in the book Rain describes a stable structure manifest as table of contents. While the formalization in First Rain, Brise Soleil by Phan is a dynamic structure in which the natural elements become subjective of atmospheric language traversing among narratives. The concepts of series and structure from Deleuze produce sense in a material substrate for atmospheric language. The concept of minor language with the case of the film Drive My Car directed by Hamaguchi shows a language of playscript reading as an atmospheric language that weighs up scenes of major languages—dialogues, language of reading lines, and multi-lingual play language.

After demonstrating Deleuze’s genesis of sense production with its material substrate of languages in relation with the above cases, the article further exemplifies the material substrate of language in the play of the game Shu created by Ye: a surface language defined by digital operation at interface, while a bodily language defined by program code and its corresponding formalization and procedural rule. Moreover, abstraction from ancient Chinese mathematical thought characterizes the digital with a material-processual view. It can bring atmospheric language a digital agent of validating the discrete states of being and becoming, that is finalizing states of computation and performing digital operation. With abstraction, atmospheric language in the middle of surface language and bodily language produces discrete states of being, which constitute lived experience of calligraphy. In what follows, I will unfold these cases and corresponding aspects of theoretical framework one by one.

Sense-Data in Hypertext

Object Speaking is a project made in 2021 by poet RELATED DEPARTMENT.1 Mu wrote 24 sentences for 24 items—such as Do Not Disturb sign, keycard envelope, room key, slipper seal, etc.—used in the hotel Chapter & Verse. The sentences use literary methods such as metaphor, literary quotation, personification, and so on to interpret the objects. Then 24 keywords from the sentences are extracted, and input in the search engines of several second-hand trading platforms such as Xianyu, Craigslist, Facebook Marketplace, and so forth, conducting exchanges between words and objects. A book Object Speaking was published at last, which collects written introductions and pictures of personal items found on those second-hand trading platforms.

A hotel is a temporary venue. People come to have short or even intimate relationships with these objects in the hotel: we use, drop, forget them, and even bring them back home. From hotel objects, scattered sentences were then assembled into collections of words, and then translated to words thrown into algorithms to produce many texts and pictures of personal items on second-hand trading platforms. The original objects are illuminated by the textual and pictorial descriptions of the second-hand items from many places. Meanwhile, the owners and potential users of these second-hand objects also have a subtle yet real connection to the people in hotel rooms, delivering faint pulses to one another.

These sentences and people are weaving a chaotic worldly net…; it is full of possibilities for upheaval and deterioration, as if it had a variable key. Opening this door and passing through it, you find yourself on an endless journey between translations without original texts. You may be lucid dreaming or sleepwalking—far from following a logical sequence of deliberate misrepresentation. (Mu 19–20)

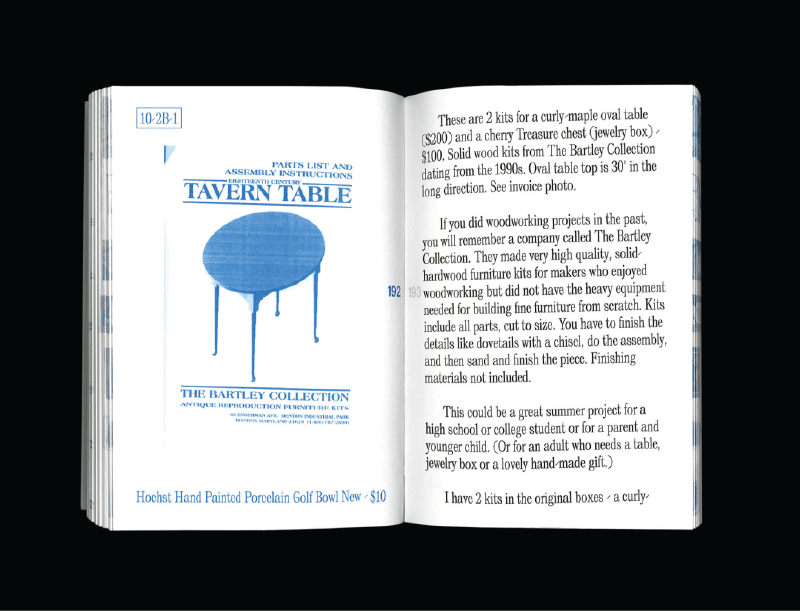

Mu’s words in the Preface of the book suggest a poetics of an ambiguous operative language. The ambiguity hides behind a series of linguistic operations from object names to sentences, translated extracted keywords to textual and pictorial descriptions linked via an index system. From hotel surface to search engine of platforms, words undergo datafication and are displayed in the form of a book (see Figure 1(a) below). Further, the index system in the book creates a format that comprises an embedded hypertext together with words and sentences on hotel object surfaces and search engine of platforms (see Figure 1(b) below). When words become data input for a search engine, they generate textual and pictorial descriptions that are media perceptible, which makes the imperceptible of computation become operative and present. This moment of sense-data makes embedded hypertext bear the weight of operative language, making the ambiguity of the operative language sensible. This means it is the formal of computation that weighs up the operative language of hypertext, as an intelligible way of being sensible to the ambiguity of operative language.

Deleuze developed his conception of an intrinsic genesis of sense via the notion of “double causation.” Double causation refers to body causality and quasi-causality. According to Deleuze, Antonin Artaud developed a kind of schizophrenic language, while Lewis Carroll established a surface language. The schizophrenic language relies on schizophrenic body, which is a sort of body-sieve that traverses bodies. The surface language, in contrast, is composed of lines that conjugate propositions and things. The schizophrenic language and the surface language not only comprise the causation of body and force, but also a “quasi-causation” between incorporeal sense-events, borrowed from the Stoic:

Incorporeal sense-events are this heterogeneous and unconditioned extra-being that subsists outside bodily states of affairs and language, and that gives rise to an internal “static genesis”, which not only produces the proposition and its dimensions (signification, denotation and manifestation), but also the individuation of bodies and consciousness. (Voss 22)

Events, in terms of incorporeal sense-events, are not causes of one another, but enter into relations of “an unreal and ghostly causality” that is always reversible (Deleuze, The Logic of Sense 33). Sense-Events express intensity.2 Deleuze’s claim that being intensive is a continuity of the sensible and the intelligible, was articulated to go beyond the discontinuity that existing philosophy had created, in order to ground thought in a metaphysics of differential calculus (Adkins, 2015). Jon Roffe explains intensity via the social: “[C]hanges in society-social dynamisms—do not involve a passage from one actual series to another, but the passage from the intensive to the extensive” (287). The point speaks to the fact that the intensive is immanent to the extensive, generating difference from within.

We can see from the sense-data in the hypertext of the above case that the intensive and the extensive are not reciprocally conditioned; intensity is qualified and quantified in extensities. The expressive intensity of a sense-event in the extensive offers a mode of understanding computation in the overall hypertext of Object Speaking. When inputting the sentence in the search engine of the trading platform, the algorithm expresses an intensity in which the output expresses a self-sufficient processing of computation itself. This means the output itself has no meaning, but is evaluated through being quantified and qualified in the context of hypertext composed of the operative language. For instance, the index system in the book quantifies and qualifies the output in the format of the book: the pictures of the original 24 objects are arranged in the order of ordinal number surrounding the book spine and text blocks (see Figure 1(a)); algorithmic results seem random, but are arranged in a precise logic of indexing. For example, 10-2B-1 means the tenth poem sentence, the second search result of the second key word, and the first picture (see Figure 1(b)). The quantifications make the book more of a means of display and a method of formatting that constitutes the operative language of words and objects. It designates a quasi-causal relationship between the words and sentences from the original 24 objects and the computational objects from the second-hand trading platforms. Sense-Data here means the algorithmic output enters an assemblage of operative language that makes data extensively known and felt. This suggests that data are quantified and qualified via the formal and the operative, allowing reading to be perceptible.

According to the Preface of the Object Speaking project, the search of keywords on second-hand trading platforms can be seen as an exchange from words to objects (Mu). In this manner, the search result begins not to correlate with the original objects, but becomes a new word constellation together with textual and pictorial descriptions of second-hand objects. They constitute an experience of riddling, which is folded by algorithms. Meanwhile, the shapes of the 24 objects in the table of contents and 24 different bookmarks display and reveal the answers to the riddle of the items from second-hand trading platforms. The experience of riddling comprises a poiesis of operative language, making it atmospheric.

Being Atmospheric: Struggling Within, Weighing Up

The atmospheric in Chinese aesthetics means a mood an artwork conveys, like an atmosphere produced by the idea-scape (yijing)3 of a poem. French sinologist François Jullien wrote that atmosphere must go beyond the materiality of things, in order to experience a feeling of floating across that does not point to anything but flickers within (52). In the Object Speaking project, the poiesis of operative language lies in the experience of riddling, while the algorithm of second-hand trading platforms, the design of the contents and text blocks (the shapes of original 24 objects), and the 24 bookmarks constitute operativity to its readers and users. The atmospheric is highly operative under digital and computational conditions.

Contemporary Western literature on atmosphere (both in its physical and metaphysical registers) in some way gives more space to think about atmospheric language and its technological conditions. Legal scholar Andreas Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos argues for an ontology of atmosphere: it “exceeds its bodies towards a collectivity that cannot be fully described or indeed prescribed” (157). Drawing upon Peter Sloterdijk’s “glasshouse”, atmosphere, for Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos, means “engineered atmosphere”, an air-conditioned partitioning where affects circulate in pre-determined way (158). Returning to the case of the Object Speaking project, operative language pre-determines the affects circulated among riddling, creating ambiguity, and redundancy.

Engineered atmospheres in art and literature can be seen to be self-regulating. This characteristic of self-regulating relates to Deleuze’s concern about the genesis of sense production. For Deleuze, the genesis of sense is produced in an extra-propositional and sub-representative field, where language is at the state of not-yet language and does not reach the level of signification. The atmospheric language this article addresses aims to make clear the structural and elemental aspects of this state of not-yet language, which is situated within the schizophrenic language by Artaud and the surface language by Carroll as mentioned earlier.

Drawing upon Friedrich Nietzsche and Structuralism, Deleuze sees the genesis of sense production in a field of forces. The quality of a force, being either active or reactive, is determined through the difference in quantity with related forces. In relation to the schizophrenic and surface languages, sense is a surface-effect brought about by the penetration of a body, and becomes incorporeal in relation to another. Sense, in this manner, is tied to a problem, defined as “an ideational objectivity or … a structure [my italic] constitutive of sense” (Deleuze, Difference and Repetition 120, 145). Structure, here, does not mean a stable and static structure. Sense is not a surface-effect of the interaction of individuated bodies; bodies are in their undifferentiated depth and in their measureless pulsation, an impersonal and pre-individual transcendental field, not to be determined as that of a consciousness. The structure therefore means structural causation among sense-events or sense-effects made to resonate by a paradoxical element of nonsense which traverses the series (Voss 20).

The atmospheric language developed in this article follows the above genesis of sense production, in the way that writing becomes an analysis of dynamics. This means, the schizophrenic and surface language comprise a field of forces, allowing the literal and the literary to be analyzed within the field of forces. To exemplify it I will take three recent examples from art, literature, and film in South-East Asia, by drawing upon the concepts of series, structure, and minor language respectively. These examples are non-digital, because I want to draw on how atmospheric language comprises a field of forces, thus allowing the formal and the operative to support and weigh up the sensible.

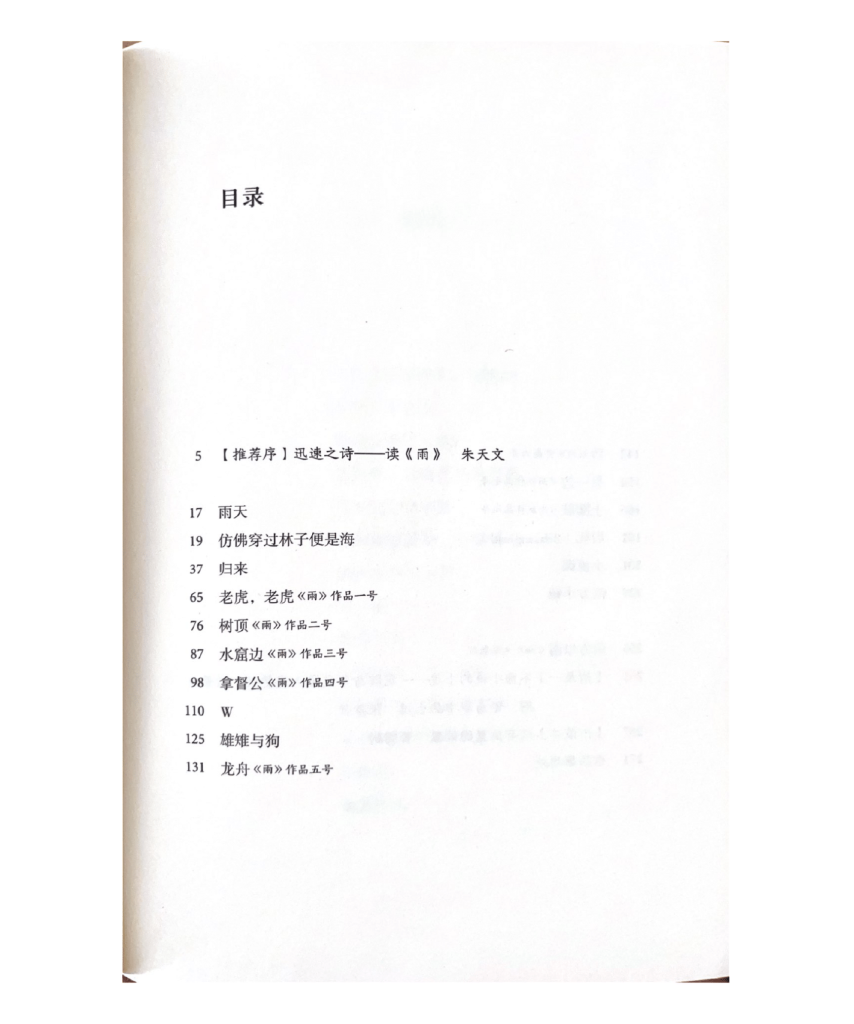

As a Malaysia-born author, Ng’s fictional works are always assigned to Mahua literature. Mahua is a multivalent term. It may be used to designate literature from former British Malaya (Malaya, in Chinese) or contemporary Malaysia (Malaixiya) that is written either by ethnic Chinese or in Chinese. Mahua points to an ethno-national category, but can also mean an ethic or linguistic one. As Ng wrote, he mixed up a number of the world’s languages to create a unique and new written language. This mixing is prevalent in much of Mahua literature, which struggles to reflect the multi-lingual environment of Malaysian society. His short-story collection Rain (2018) collects 16 short stories. Among these stories, Ng borrowed the naming method from painting, to name 8 stories that depict rain as Title 1, Title 2, Title 3 … until Title 8 (see Figure 2 below). Ng wanted the reader to see these works as small pieces of paintings with finite space and elements, allowing works to vary, fork, rupture, and continue.

Outside the series (Titles 1 to 8) from Rain, there are also pieces depicting rain. In the foreword of Rain, Taiwanese fiction writer T’ien-wen Chu described Ng’s work as a metamorphosis that tells the difference and nuanced relationship between works that depict rain outside the series and those within the series named after rain. Chu wrote, the metamorphosis in Ng’s work is rooted among the blurred boundaries of different worlds; gods, human beings, and nature permeate each other. They do not form a hierarchy or belong to particular classes. They intertwine, allowing forces to collide and counteract (7). In the collection, the protagonist Xin traverses all stories. In some pieces, Xin is only 5 years old; in another Xin is a youth in the prime of life, narrated in the tone of second-person; in yet another, narrated in the third-person. These switches between different tones are in a network of relations. They are all basic elements and undergo multiple connections, showing a metamorphosis from spirit to appearance. This metamorphosis is a poetry of speed (Chu 11).

More importantly, outside the series, some stories can be seen as constituting the background of the series. For instance, in the story W, a sad girl becomes the basic element that varies in other stories. In the story Return, an uncle of Xin who favors storytelling is imaginative. His tone of storytelling makes the reader of the short stories to have a sense that all the stories from the series seem to be told by the uncle. In the story A Novel Class, a girl is writing her novel. She writes, “autobiography must be hidden in the depth of background” (Ng 216). This sentence seems to suggest the whole book is written with the hint of autobiography.

According to Deleuze, the genesis of sense production requires a structural factor, in which series create tensions of forces and converge into singularity (“How Do We Recognize Structuralism?”). In the case of Rain, stories outside the series of rain (Title 1 to 8) formulate different series in their own ways. They weigh up the textual bodies of the series of rain and effectuate the sense-events of it. The table of contents in this book forms a surface language, manifesting the quasi-causality of rain: it, on the one hand, shows the traces of tensions of different series across the stories outside the series of rain and those in the series of rain; on the other hand, the different series that make tensions converge into the theme of rain, making itself become singular.

The table of contents of Rain shows a stable structure in the production of sense. In the multi-channel video work First Rain, Brise-Soleil (2021) by the Vietnam visual artist Phan, however a dynamic structure in which the natural elements become subjective of atmospheric language is created. It shows struggles within a series of atmospheric language. In the first story of the video, Phan speaks about a Vietnamese builder working on a theatre in Cambodia that was later burned due to careless construction. Phan’s artworks are good at exploring historical and ecological issues in Vietnam, and complex identity issues at the border across the Mekong River—often in a poetic and less documentary narrative. The video is displayed across three screens.

In one scenario, the screen in the middle shows an animated illustration of the theatre being burnt. The screen on the right side shows a girl holding a purple fan to hide her face, and the screen on the left side shifts to a construction site upon which a crane works. In these sequences, a handful of soil suddenly is thrown upon the fan from the left of the screen on the right side (Figure 3). Together with water and fire, soil as a natural element in this video makes a different series of narrative converge and traverse the three screens at this moment. This connection soon disappears with moving images: it suggests a singular moment when a natural element in the background of moving image emerges and traverse different narratives. The moving image of video gives us a dynamic structure of sense production. At the same time, the atmospheric language composed by natural elements is secondary to the main stories. It belongs to a minor language or not-yet language. When the natural element converges, it reaches a threshold of becoming major language.

The Japanese film Drive My Car (2021) can exemplify a secondary language that struggles under major language and weighs elements of major languages. The film is directed by Ryûsuke Hamaguchi, written by Hamaguchi and Takamasa Ôe, and adapted from a short story by Haruki Murakami. The film tells a story about a theatre actor and director Yūsuke Kafuku. Kafuku’s wife Oto was a playwriter who conceived her stories during sex and narrated them to Kafuku. Kafuku once found his wife having an affair with an actor Kōji, but did not disturb them. Oto soon passed away from a brain hemorrhage. Two years later, Kafuku accepted a residency in Hiroshima, where he directed a multi-lingual adaptation of Anton Pavlovich Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya. He gradually opened up to his driver Misaki, who also had an unbearable secret in her life. They sympathized with each other and finally Kafuku played the role of Vanya, giving an impassioned performance.

There are different kinds of languages in the film. The language of reading playscript, which was recorded in tapes by Oto, while Kafuku learns to read his lines when driving his car. The multi-lingual languages of reading playscript in rehearsal and public performance by casts from different countries: Japanese, Mandarin, Korean sign language, Korean, and English. Throughout the film, the playscript of Uncle Vanya is like a ‘body-sieve’ of text traversing the dialogues and scenes of the film. More specifically, there are several scenes where reading lines intersects with Kafuku’s inner voice, but in an ambiguous way. The intertext happens under the condition that the contents of the playscript and the referred scenes have their own independent context, but simultaneously intersects within the language of reading lines. Moreover, the language of reading lines becomes multiple in many ways: from Kafuku’s own reading when driving the car, Kafuku’s reading when Misaki drives the car, to collective reading with casts, and scene rehearsal with dialogues between different roles in different places such as a garden and theatre stage. In these ways, the language of reading playscript throughout the film comprises an atmospheric language, it constitutes dramatic conflicts within scenes by weighing up scenes of major languages—dialogues, language of reading lines, and multi-lingual play language.

In discussing Franz Kafka and minor literature, Deleuze and Félix Guattari analyze the impossibility of writing via an artificial language that deterritorializes the strata of major language, although it is constructed within it. According to them, Kafka turned the major language German into an “essay language”, a “materially intense expression” “in its very poverty”, differing from another attempt at symbolic reterritorialization that swells German up “through all the resources of symbolism, of oneirism, of esoteric sense, of a hidden signifier” (Deleuze and Guattari 19). The notion of “essay language” suggests a becoming language as not-yet language in its materiality, a nascent state of the pre-verbal as a way of interfering with the rigidified mode of language. Deleuze and Guattari are pointing to the sensible and its varied intensities in material differentiation. It offers an ontological way of knowing and experiencing language and of becoming language. In Drive My Car, the language of the playscript reading not only mobilizes material forces of events, it also reveals the struggles within, in the way that the playscript is read in fragments. In this manner, it does not become a formal language, it works under and weighs up major languages.

Another Abstraction and its Discretion

Shu (Calligraphy, 书) (2022a) is an online game developed by Ye. The game was created within the 48 hours of the Ludum Dare 50 competition. The game is a play on calligraphy. Inspired by the paintings of Jackson Pollock and Guanzhong Wu and the calligraphy of Dongling Wang, each pass of the game allows the player to draw abstractly.

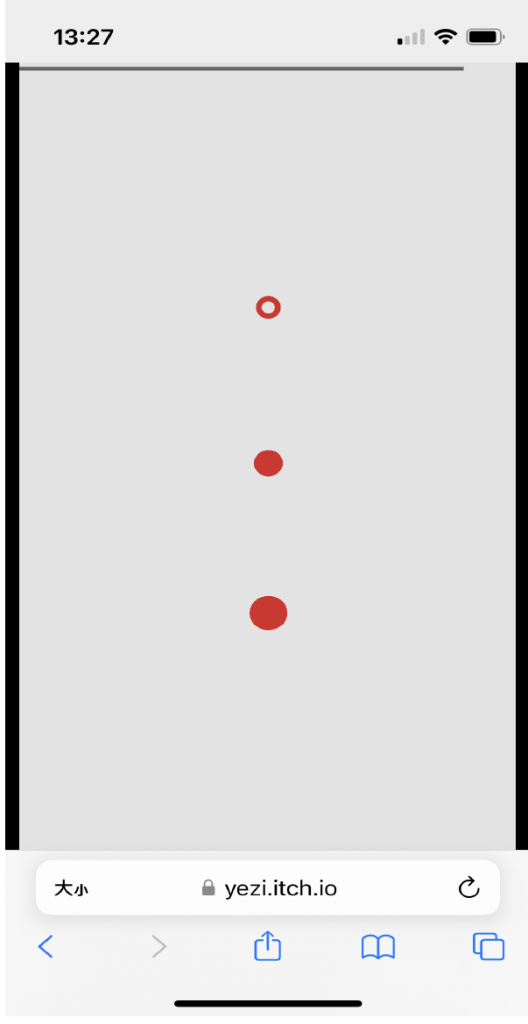

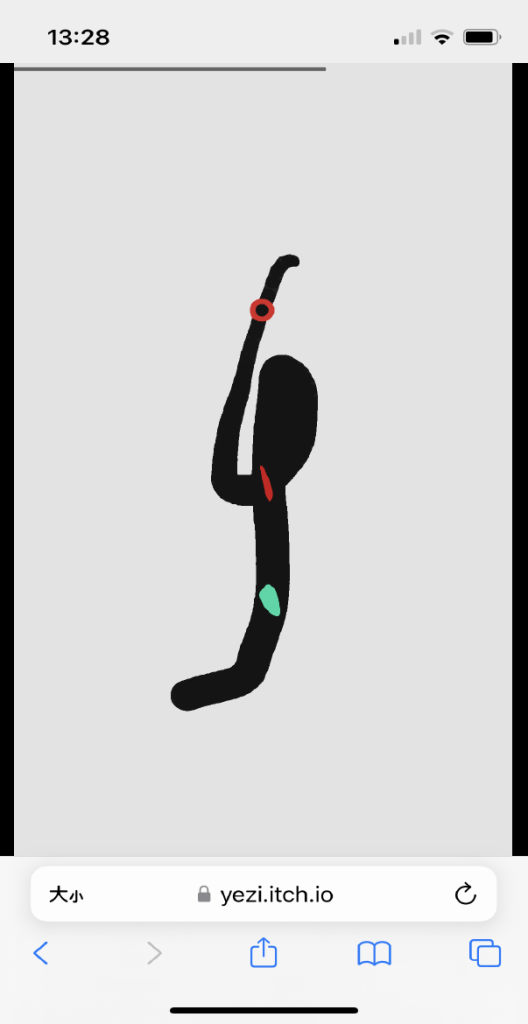

As Ye said, he wishes to capture writing in the game: how to manipulate soft, sometimes uncontrollable writing, and experience the aesthetics of smooth writing (“Calligraphy Game”). There are three icons for the game. One is a solid dot. Two is a hollow ring, while a virtual slim pen is needed to manipulate lines and their speeds, in order to pass through. The third is an arrow indicating the direction of the slim pen. Accordingly, there are four steps of guidance for the play of the game: 1. Cover the solid dot with a thick brush; 2. Pass through the ring with a fine pen; 3. In the direction of an arrow, passing through the fine pen; 4. Try to trigger all the targets (icons) in one holding touch (“Calligraphy Game”). Figures 4 show a trace of calligraphy after one round of play. In each round, there is a pattern of the three icons, player needs to adjust their touch, in order to draw by following the above guidance. For example, in Figure 4(a), there is one hollow ring and two dots with varied sizes. The player needs to touch like a slim fine pen first to pass through the hollow ring, then cover the two dots with varied strength. Figure 4(b) shows one result of drawing. The red shape in the middle and the green one below is shown when a drawing follows the guidance. The rules of the game—including the round of the game, the patterns of icons in each round, and the guidance—are formalizations that constitute an atmospheric language. For instance, the guidance spatializes interface, and locates each icon in a system of positioning; at the same time, each round and its drawing happen in the real time of algorithmic implementation. These formalizations together support and condition the continuity of drawing.

clamp((1-PenTips.MoveTo.Speed/2500),0.05,1)*penSize

mose = 100-PenTips.MoveTo.Speed/100 (“Calligraphy Game”)

This above initial program code defines the rhythm of calligraphy in the game. This definition was made by computation, that is, the formal and discrete determines the rhythm of calligraphy in the game. Together with the above-mentioned rules of the game, the program code constitutes a bodily language of the game that conditions play. Moreover, the operations of digits via three icons on smartphone constitute a surface language that makes present of discrete states of being in real time. Every digital operation on a smartphone finalizes each execution of the program code. It in this way validates the program code and produces states of being and becoming. This material substrate of bodily language and surface language allows us to consider the concept of abstraction in a material-processual view, which characterizes the digital as a force in a linguistic field of dynamic analysis.

The notion of abstraction from ancient Chinese mathematical thought can shed light on our understanding of a material-processual view of abstraction. French historian of mathematics and sinologist Karine Chemla asserts that abstraction in ancient Chinese mathematics is different from formal abstraction in Western mathematics. Referencing French engineer and sinologist Edouard Biot, Chemla points out how the way ancient Chinese mathematical practice deals with knowledge lies not in theorizing—i.e. adopting a higher abstract viewpoint—but is characterized by its emphasis on the practice and application of rules. Writing in ancient Chinese mathematical thought records procedures of practice. Procedures are prescriptions: the use of writing is a way of obeying orders. The use of mathematical problems suggests not the idea of proving, but of checking rules through their application (Chemla 297–298). That is to say, abstraction in ancient Chinese mathematical thought does not mean generalization of theory and its application to other domains of knowledge. Rather, it is a practice of generality that “allows practitioners to bring different domains of application into relation to each other through the development of a higher form of knowledge running across them” (Chemla 301).

Citing Chapter 2 of the ancient classic The Nine Chapters of Mathematical Art (Jiuzhang Suanshu), Chemla shows how abstraction organizes different units of grains through two mathematical media: tong1 (making communicate, 通) and tong2 (equalizing, 同). The two mathematical media come from the classic’s commentator Liu Hui’s comments on the text. They constitute the procedure and rule of measuring types of grain. According to Chemla, “making communicate” implies the work of generality, while “equalization” is an important step of procedure that doubles abstraction: an algorithmic process towards equalization, on one hand, means abstraction refers back to check the validity of the procedure itself; on the other hand, it implies the pursuit of intention and meaning as a result of problem-solving (Chemla 313–314).

The two mathematical media—making communicate and equalizing—enable abstraction to be thought in a material-processual way, in which the formal and the operative constitute a processual structure. In the material substrate of atmospheric language of Shu, digital operation finalizes each execution of the program code, while communicates with the algorithmic implementation. It in this way validates the program code and produces states of being. The abstraction from ancient Chinese mathematical thought allows intensity to be re-considered within sense-events of the extensive in a way such that intensity is not virtual, but weighed up and/or struggling within atmospheric language supported by data formation and operation.

According to Deleuze, the opposite of the abstract is not the concrete, but the discrete; and the concrete can be pursued only at the expense of the discrete (353–354). According to Brent Adkins, Deleuze’s use of the word abstract is another way of thinking about the intensive. In Hegel’s philosophy, the abstract is opposed to the concrete, whereas Adkins argues that Deleuze thinks of the abstract in opposition to the discrete, as cited in one of Deleuze’s lectures in his process of writing A Thousand Plateaus (Adkins). This does not suggest that the abstract is the continuous. Rather, referring to the double causation in schizophrenic and surface languages, the abstract is a diagram of sense-events, while sense-events are ratios of the extensive and the intensive. As Adkins points out, the dualistic pairs in A Thousand Plateaus—such as … the extensive and the intensive—are not types or things but tendencies toward stasis or change; there are no different kinds of beings but only differences in degree, a ratio of the concrete and the discrete (Adkins 353).

Adkins further introduces Deleuze’s argument that the abstract is lived experience, by quoting another of Deleuze’s lectures on lived experience and time. “To speak about lived experience in the context of time as an empty form is to speak about lived experience as an intensive magnitude that fills time, and this is what Deleuze calls here ‘abstract’.” (Adkins, 356). The filling of time suggests that an atmospheric language supports the filling. This can be seen in Deleuze and Guattari’s discussion on rhythm: “Rhythms are also abstract, not in the sense that is opposed to concrete but in the sense that is opposed to discrete. To make a rhythm discrete is to make it into a cadence, to turn life into a series of extensive points rather than degrees of intensity following a line.” (Quoted in Adkins, 357). Here, life is lived in rhythms; it is the very concreteness of life itself. The abstract here is intensive and concrete life, it is opposite to the discrete and extensive.

Deleuze builds a continuity of the sensible and the intelligible, to go beyond the discontinuity that existing philosophy had created, and to ground thought in a metaphysics of differential calculus. To be specific, in the history of Western philosophy, the stability of a thing is attributed to its intelligible nature, while the thing’s ability to undergo change is attributed to its sensible nature. The property relating to the thing’s intelligible nature is its essence, while the properties relating to its sensible nature are its accidents (Adkins, 5). Moreover, previous images of thought that attempt to ground difference are in the unity of representation, which institute a discontinuity between the representation and what it governs (Adkins, 11). With these considerations, a metaphysical calculus becomes a way of thinking difference in itself, of thinking the continuously variable nature of an Idea (Adkins, 6). In the case of the game Shu, the idea of calligraphy is realized by its discrete formal and operative. Here the abstract means another material-processual view, which lies in validating the discrete states of being and becoming, that is finalizing states of computation and performing digital operation. Atmospheric language is secondary in that the formal and the operative express a bodily causation. It weighs up states of being and becoming as quasi-causation, manifesting as sense-events of drawing abstractly. Atmospheric language in this manner is Deleuze’s abstract machine. However, it is not the continuous sensible and not the virtual intensive that produces a genesis of sense, but the intelligible—the material-processual abstract, the formal and the operative—that makes difference in producing discrete states of being and becoming.

Conclusion

Sense-Data and atmospheric language aims to show how the digital, characterized by place value and abstraction, is an agency of mobilizing medial and technical milieu to generate states of being and becoming. The article draws on cases that have their own mediality and materiality, and combines case studies with aspects of Deleuze’s theory of a genesis of sense production. In the book project Object Speaking, book is not constrained to be an end product, but a structural process in which sense-data are quantified and qualified via the formal and the operative. Sense-Data as positional notation reveals its place value in the material process of the book, in the way that the extensive formalization and operation support the knowing and experiencing of data.

To further exemplify the linguistic practice of how media language supports and bears different cultural forces, the article moves to three examples that draw on Deleuze’s concepts of series, structure, and minor language respectively. The book Rain and the moving image First Rain, Brise Soleil show the structural materiality and processuality of atmospheric language, while the film Drive my Car manifests that, atmospheric language is a minor language that weighs up or struggles within other languages. These conceptual elements reflect that the field of linguistic practice, which can relate to Deleuze’s linguistic paradigm of double-causation, is full of cultural forces which interact with atmospheric language.

In the case of the game Shu, a material-processual view of abstraction was introduced in understanding how algorithm implements discrete states of being and becoming. Via abstraction, operation of digits communicates with the formalization of algorithm, which includes execution of program code and discrete states of being based on rules and procedures of the game. These operation and formalization situate atmospheric language within the linguistic paradigm of double causation by Deleuze. The atmospheric language in this way weighs up states of being and becoming as quasi-causation, manifesting as sense-events of drawing abstractly.

Sense-Data and atmospheric language in this article offers a linguistic perspective of understanding the mediality and materiality of digital aesthetics. With the above cases, the medium book constitutes its technical milieu that reveals individual material difference, in this manner shows the diverse material and medial phases of the atmospheric. As a media language, atmospheric language can generate sense production based on data formation and its operation and formalization. More so, atmospheric language is secondary to other languages and states of being. This attests to the fact that atmospheric language, as a particular media language of sense-data, supports and bears linguistic states of being and becoming. The sense-data and atmospheric language also renews some aspects of Deleuze’s linguistic theory of double causation, in a way that the digital (positional notation and abstraction) drives media languages in the middle of bodily language and surface language. Its related operation and formalization condition linguistic being and becoming, suggesting a materialized intelligible produces discrete states of being sensible.

Endnotes

[1] The idea and graphic design of this project come from RELATED DEPARTMENT. The 24 sentences and Preface are written by Mu. The project is also supported by a hotel Chapter & Verse and an independent publisher Pulsasir.

[2] The notion of intensity couples with extensity mainly in Deleuze’s later works. For most of the time, Deleuze did not analyze in depth how the intensive works with the extensive so as being identified as “difference-in-itself”. He expanded that life is immanent and intensive in What is Philosophy? See Gilles Deleuze, and Félix Guattari. What is Philosophy? Translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Graham Burchell. New York: Columbia University Press, 1991.

[3] Idea-Scape (Yijing) is a literary device in Chinese literature. It creates a poetic realm consisting of a series of images, in which yi (idea) and jing (scape) fuse the metaphysical and the physical, engender each other, evoking, and opening up aesthetic imagination.

Works Cited

Adkins, Brent. “Who Thinks Abstractly? Deleuze on Abstraction.” The Journal of Speculative Philosophy, vol. 30, no. 3, 2016, pp. 352–60.

Chemla, Karine. “Abstraction as a Value in the Historiography of Mathematics in Ancient Greece and China: A Historical Approach to Comparative History of Mathematics.” Ancient Greece and China Compared, edited by G. E. R. Lloyd, Cambridge University Press, 2018, pp. 290–325.

Chu, T’ien-wen. “Foreword.” Rain, Sichuan People Press, 2018, pp. 5–13.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature. Translated by Dana Polan, University of Minnesota Press, 1986.

---. What is Philosophy? Translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Graham Burchell, Columbia University Press, 1991.

Deleuze, Gilles. Diffrence & Repetition. Translated by Paul Patton, Columbia University Press, 1994.

---. “How Do We Recognize Structuralism?” Desert Islands and Other Texts 1953-1974. Edited by David Lapoujade. Translated by Michael Taormina, Semiotext(e), 2004, pp. 170–92.

---. The Logic of Sense. Translated by Mark Lester. Columbia University Press, 1990.

Ernst, Wolfgang. “Existing in Discrete States : On the Techno-Aesthetics of Algorithmic Being-in-Time.” Theory, Culture & Society, vol. 38, no. 7–8, 2021, pp. 13–31.

Drive my Car. Directed by Ryûsuke Hamaguchi. Bitters End, Bungeishunju, C&I Entertainment, 2021.

Fazi, M. Beatrice. “Digital Aesthetics: The Discrete and Continuous.” Theory, Culture & Society, vol. 36, no. 1, 2019, pp. 3–26.

Fazi, M. Beatrice, and Matthew Fuller. “Computational Aesthetics.” A Companion to Digital Art, edited by Christiane Paul, Wiley Blackwell, 2016, pp. 281–96.

Jue, Melody. Wild Blue Media: Thinking Through Seawater. Duke University Press, 2020.

Jullien, François. The Ode to Dan: On Chinese Thought and Aesthetics 淡之颂:论中国思想与美学. Translated by Esther Lin. East Normal University, 2017.

Krämer, Sybille. “Writing, Notational Iconicity, Calculus: On Writing as a Cultural Technique.” MLN, translated by Anita McChesney, vol. 118, no. 3, 2003: 518–37.

---. “From Dissemination to Digitality: How to Reflect on Media.” Media Theory, vol. 5, no. 2, 2022, pp. 79–98, https://journalcontent.mediatheoryjournal.org/index.php/mt/article/view/147.

---. “Mathematizing Power, Formalization, and the Diagrammatical Mind or: What Does ‘Computation’ Mean?” Philosophy and Technology, vol. 27, no. 3, 2014, pp. 345–57.

Mu, Yongquan. “Preface.” Object Speaking, 1st ed., Chapter & Verse, 2021.

Ng, Kim Chew. Rain. Sichuan People Press, 2018.

Peters, John Durham. The Marvelous Clouds: Toward a Philosophy of Elemental Media. University of Chicago Press, 2015.

Phan, Thảo Nguyên. First Rain, Brise Soleil. 2021-ongoing. Times Museum, Guangdong. Video.

Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos, Andreas. “Withdrawing From Atmosphere: An Ontology of Air Partitioning and Affective Engineering.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, vol. 34, no. 1, 2016, pp. 150–67.

Roffe, Jon. “Deleuze’s Concept of Quasi-Cause.” Deleuze Studies, vol. 11, no. 2, 2017, pp. 278–94.

Voss, Daniela. “Deleuze’s Rethinking of the Notion of Sense.” Deleuze Studies, vol. 7, no. 1, 2013, pp. 1–25.

Ye, Zitao. “Calligraphy Game 书法-游戏”. Yzitao. 2022b. https://yzitao.notion.site/636fd6b576c34f4b83898b8e575d2d2a.

---. Shu. HTML5. 2022a. Game. https://yezi.itch.io/shu.

Footnotes

-

The idea and graphic design of this project come from RELATED DEPARTMENT. The 24 sentences and Preface are written by Mu. The project is also supported by a hotel Chapter & Verse and an independent publisher Pulsasir. ↩

-

The notion of intensity couples with extensity mainly in Deleuze’s later works. For most of the time, Deleuze did not analyze in depth how the intensive works with the extensive so as being identified as “difference-in-itself”. He expanded that life is immanent and intensive in What is Philosophy? See Gilles Deleuze, and Félix Guattari. What Is Philosophy? Translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Graham Burchell. New York: Columbia University Press, 1991. ↩

-

Idea-Scape (Yijing) is a literary device in Chinese literature. It creates a poetic realm consisting of a series of images, in which yi (idea) and jing (scape) fuse the metaphysical and the physical, engender each other, evoking, and opening up aesthetic imagination. ↩

Cite this article

Li, Mujie. "On Digital Aesthetics: Sense-Data and Atmospheric Language" Electronic Book Review, 4 June 2023, https://doi.org/10.7273/242e-se92