Global Politics and the Feminist Question

Ara Wilson writes a riposte on the gathering of "waves" essays; she points out that global feminist politics provides a necessary perspective on debates about the current state of feminism.

Ara Wilson writes a riposte on the gathering of “waves” essays; she points out that global feminist politics provides a necessary perspective on debates about the current state of feminism.

In the 1990s, international feminist organizing adopted new forms and operated in different sites. Particularly in the third world (or global south), the UN and its myriad conferences became a key focal point for political work. Groups refashioned themselves as non-governmental organizations (NGOs), the legible and legitimate form of social mobilization on a transnational stage. This mode of political work reached its apogee at the 1995 UN World Conference on Women in Beijing, where 30,000 participants met at the NGO Forum outside the city, mostly women, and including activists for disabilities, peasants, colonial struggles, and lesbian rights. This organizing took advantage of the new media of the Internet and email as well as the standbys of progressive politics: the newsletter, phone call, or meeting and produced countless documents, buttons, tote-bags and t-shirts. It funneled the radical energies of post-colonial struggles, democratization movements, labor organizing, and women’s movements into the liberal discourses of human rights, under the legitimating auspices of the United Nations. From a global perspective, this was the major expression of feminism in the 1990s.

The emergence of transnational feminist networks illustrates a few simple points about politics in the current world order characterized by post-Cold War realignments and globalization. First, so much of politics articulates on a transnational scale, whether through the United Nations or the World Economic Forum in Davos. Second, the emergence of NGOs demonstrates how struggles for rights and redistribution are grappling with the changes to governments, as states have been refunctioned with privatization, militarization, and capital flows. The state is not the only arbiter of politics yet it remains a crucial hub. Feminists have to address the new modes of governance by states and non-states, which have been referred to variously as neoliberalism, new constitutionalism, or empire. This is another way of saying that feminist praxis unfolds within conditions of globalization. On one hand, features of globalization foster new modes of feminist politics, like women’s entry into transnational spaces that permit their organizing, or famously, the use of the Internet and communication technologies - and the UN and NGOs stage regular discussions about gender and ICT.The organizational culture of these UN/NGO conversations is captured in David Nobes’ review for ebr of the 2003 World Summit on the Information Society. (Isis is one organization in the Global South.) At the same time, globalization also fosters effective opposition to feminist politics, notably by politicized theological forces - evangelical Christians, the Vatican, and Islamic voices, which arrive at a surprising degree of ecumenical consensus concerning reproductive issues or gay and lesbian concerns.

I raise the rather bland realm of UN conferences as a way to relocate the ebr thread on feminism in a global and political frame. Lisa Yaszek wants us to think about “feminist activity as something that changes over time in relation to specific historical and material conditions.” Yet reading the ebr debates about post-feminism or feminist `waves’ after observing changing feminist activity in Asia, Africa, and Latin America produces the feeling I have stumbled into the wrong meeting. The ebr pieces here present political activism as a prior ground: as Yaszek notes, “those feminist practices that secured important rights for women in the past but that no longer seem to address the complexities of women’s lives in a technology-intensive era of global capitalism.” The mode of politics in the ebr debates, the argument about what feminism is or should be here, is about language, aesthetics, and concepts: as Laccetti suggests, politics “bound up with a certain kind of language.” Their political horizon is writing - texts, media, cultural production. That cultural production is a form of politically engaged praxis is something of a given in contemporary feminist thought, itself an achievement of the deep revisions that feminist and allied movements inflicted on established conceptions of the political. And many waves of feminists have been reflecting on the politics of form. What might the forms, content, and sites of feminist political action do to recast debates about the category of feminism?

The locus and focus of the ebr feminist thread - within the first world (or the North Atlantic), and on the politics of form/language/media - limits the ability to answer its very questions about feminism. A number of authors repeat often-heard claims that `third wave’ or post-feminism is more sensitive to axes of social difference than was the second-wave - that it includes “a broader chorus of voices, classes, races,” writes Guertin. Yet the ebr pieces remain provincially bound to domestic discourses in the U.S., Europe and perhaps Australia. Moreover, they interpret the shift in primarily theoretical terms, as a transformation in thinking. This idealism makes race an analytical category, more than a material effect of social relations. Elisabeth Joyce’s inauguration of a revamped focus on “waves” risks reinscribing the presumed errors of the second wave: “feminism needs to reconceive itself in terms of unity.” This unity has been questioned theoretically, ethically, and politically in terms of challenges that are especially dramatized on the international stage, where women navigate their positions in occupied territories, exploited classes, or subordinated ethnicities with their gendered agendas. (The cultural critic, Ien Ang, has suggested that feminism let go of its aspirations for agreement across differences and allow for an absence of unity.Ien Ang, “I’m a Feminist but…: ‘Other’ Women and Postnational Feminism,” in Barbara Caine & Rosemary Pringle (eds.), Transitions: New Australian Feminisms. St. Leonards: Allen & Unwin, 1995, pp. 57-73. )

Whatever its declared irrelevance, feminist political action is still unfolding on a global scale. Advocates in post-colonial settings have embraced the rubric provided by (second-wave) analysis of violence against women or gender-based violence, modifying the language for local contexts but strategically using the concept of human rights to challenge the patriarchal conjunction of threatened communities and neoliberal states. Feminists have formed new alliances (notably, with moderate religious voices, labor, and liberal democratic states) and made new elaborations of claims for justice or equality. A quick example is the mutation from population control to family planning to reproductive health and then to reproductive rights and including sexual rights. However confined “rights” might be, framing questions about women’s fecundity in terms of rights to control their sexual practice, including rights to knowledge, the ability to refuse (the state, community, husbands), and even the right to pleasure have radical effects. This reframing was a consequence of feminist political effort that still falls within the rubric of the second-wave. The World March of Women is a project that began in Montreal with quite basic second-wave claims, yet it is generating energetic participation in a series of events across the world. In this way, waves that reconfigure and regather, to use Joyce’s terms, better captures the present unfolding of gender politics than does a post-al model.

This is not to say that the transnational feminist organizing offers an enticing model of radical efficacy. Working through the liberal discourse of human rights and in conjunction with states risks accommodating global powers, as Gayatri SpivakIn a series of talks and essays since 1995, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak has criticized global feminist projects that take place through the UN or NGOs. See “‘Woman’ as Theater,” Radical Philosophy January/February 1996. For a more sympathetic analysis of feminism in the UN orbit, see Ara Wilson’s “The Transnational Geography of Sexual Rights” in Truth Claims: Representation and Human Rights. Eds. Mark Philip Bradley and Patrice Petro. 253-265. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2002. and others have pointed out. Feminists also face their version of the waves or post debates. International feminist activists bemoan the lack of younger women in their ranks. At a feminist meeting at the 2005 World Social Forum in Porto Alegre, one of the most common questions was,See Catherine Eschle’s article, “‘Skeleton Women’: Feminism and the Antiglobalization Movement,” Signs 30(3) Spring 2005: 1741-1770. “where are the young women?” Those vibrant throngs of young women at Seattle in 1999 and in the anti-globalization movements: why aren’t they more involved in feminism? The solution proposed was to “popularize” feminism through the forms of popular media (top-ten countdowns was one idea) and vague calls to “incorporate” younger women into feminist spaces and networks. But what I saw of younger female activists at the World Social Forum represents a new generation of progressive women: they were not making coffee for male movement leaders. The generational question, then, is also international. Is this another international third wave, young radical women who assume feminism but want to focus on the world? Or is this one of the new subjectivities that Guertin holds characterize a post-feminism that is transforming, not succeeding, second-wave feminism? How do debates about feminism internationally, especially in the “third world” (or global south), echo or modify the “first world” anxieties about marking feminist differences?

Attention to feminist international politics recasts a North Atlantic, critical-theory discussion of `whither feminism’ in a broader material and political frame that generates new paths for textual questions. When I teach Donna Haraway’s 1985 “Manifesto for Cyborg” piece,“Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology, and Socialist Feminism in the 1980’s.” Socialist Review 80 (1985): 65-108. I tell students of its origins: Socialist Review invited Haraway to respond to the question, “wither socialist feminism?” Haraway’s piece is fruitfully read as a response to this query, alerting us to the (then) ascendant Christian conservative movement and the dangers of Edenic thinking in the search for politics before or outside the present. The sweated labor of third-world women produced by post-Fordist global capital shifts was integral to her argument. I am proposing that the discussions about feminist aesthetics and cyberactivism again attempt this scope, and situate its questions more geographically, understanding geography in its post-Cold War, post-colonial, post-9/11, post-modern - though not necessarily post-feminist - forms.

How do efforts around narrative and representation (and the theories that inform them) intersect with current feminist political work? What is the relation of this transnational feminist organizing and the feminist efforts in narrative, cyberactivism, or theory outlined by the ebr authors? Might the “nodes” model of cyberfeminists described by Guertin apply to disparate clusters of feminists operating in loose and strategic networks? Do they exhibit “fluid, nonlinear political strategies” marked by Yaszek? The aesthetics of international feminist projects, like the UN, is decidedly instrumental, with its assumptions of transparent media and a desire to “popularize” ideas. Very few have taken on the formal analysis of these abundant texts of these arenas: their use of the Web for organizing, attempts at inclusive representational practices, strategic deployment of language of precedence, writing by committee and the bracketing of controversial terminology, or use of measurements or statistics. Is this feminist production utterly divided from the reflexive experiments of cyber or narrative creation outlined by ebr reviewers? Are there commonalities, like the reliance on images of “networks”?Annalise Riles is an anthropologist-JD who analyzes the forms of globalization, including feminist graphics oriented to the 1995 UN Beijing conference, through which she demonstrates how the trope “network” has become a formalized, reified trope. See A. Riles, The Network Inside Out. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 2000. Or are the playful efforts of international feminists, beyond the stern discipline of the UN, more salient to the reflective experiments of artists?

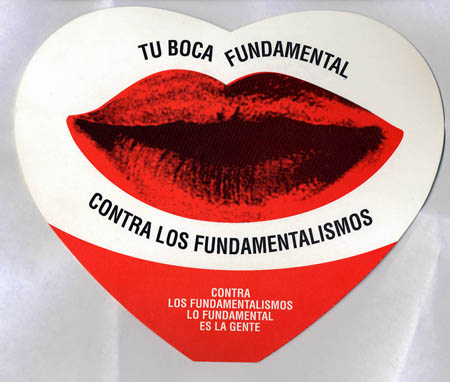

“Tu Boca. Your Mouth, Fundamental Against Fundamentalism. Against Fundamentalisms, people are fundamental!” A fan handed out at the 2005 World Social Forum in Porto Alegre as part of a campaign against fundamentalisms by the Articulación Feminista Marcosur.

“Tu Boca. Your Mouth, Fundamental Against Fundamentalism. Against Fundamentalisms, people are fundamental!” A fan handed out at the 2005 World Social Forum in Porto Alegre as part of a campaign against fundamentalisms by the Articulación Feminista Marcosur.

In the last few years, many of the progressive feminist networks that have been active in the UN orbit have turned their attention to the anti-globalization (or alter-globalization) movements, and staked ground in the World Social Forum. This shift has allowed participants to let their leftist slips show, to resurrect radical vocabulary applied to new realities, like the increasing powers of religious fundamentalism that Haraway alerted us to 20 years ago. Feminists’ entry into the anti-globalization milieu has also reinvigorated old questions once summed up as the “unhappy marriage between Marxism and feminism:” What is the relation of feminist efforts to other progressive, alternative, left, anarchists efforts? This echoes Karim A. Remtulla’s question, “What makes cyberfeminist hacktivism that contributes to the discourse on postfeminism so different from hacktivism in general?” It invites the feminist critical engagement of leftist works, such as Negri and Hart’s Empire or Multitude, or the manifestations of the World Social Forum, or questions about globalization found in literature (e.g., Reiichi Miura) or art activism and intellectual property (Caren Irr).

Feminist efforts for basic rights - to land, full citizenship, or to choose a sexual partner - has unfolded in transnational arenas in order to apply the moral force of “the international community” or UN conventions on governments. When these struggles took place through UN and government channels, much of the language and strategy was dictated by those sites: that is, liberal politics constrains the form and shapes the content of feminist projects. But at the World Social Forum, with the slogan “Another world is possible,” I found that the specific content of feminism was less clear. What were specifically feminist critiques of globalization, aside from pointing out specific ways that militarization and impoverishment harm women? Whether post-feminist or third-wave feminist or post-colonial feminist, progressives need to cultivate alternative feminist visions of governance and political economy. Alongside fluid, situational, nonlinear, and diverse aesthetic practices and political strategies, feminism needs normative theories. The question for cyberactivism and experimental narratives might be, what are the feminist norms generated through alternative aesthetics forms? Considering feminist political and representational practices together, and beyond Eurocentric boundaries, reframes the question of generations in terms of an investigation of the form and content of feminist praxis.

Acknowledgments

My research on transnational feminism was underwritten by a Seed Grant from the College of Arts & Sciences, The Ohio State University. I wrote this essay supported by a grant from the NEH (for a very different project).

Cite this essay

Wilson, Ara. "Global Politics and the Feminist Question" electronic book review, 18 March 2006, https://electronicbookreview.com/publications/global-politics-and-the-feminist-question/