2020

Bouchardon and Mayer in this essay question the narrative model of personal identity – the idea of the self as a story – in light of contemporary forms of electronic literature.

Working with a custom-coded, automated-art-system of their own devising, Australian digital artists Karen Ann Donnachie and Andy Simionato have now archived a literary corpus for future study in what they have called The Library of Nonhuman Books. Yet it remains uncertain whether human scholars will visit Donnachie's and Simoniato's virtual library. Seeing as how "there are no human ‘typewriters’ now, how can we be sure there will still be human ‘readers’ in the future?"

In this keynote, presented at the 2019 Electronic Literature Organization conference in Cork, Ireland, Anne Karhio highlights the importance of electronic literature as no less peripheral in its own construction of social, cultural, networked communities and material geographies. By looking also at recent scholarship on digital infrastructures, media archaeology, and new materialist approaches to communications technology, Karhio delineates changes that emerge from the margins, "from experimentation and risk-taking that questions established conventions, and canons, and flickers at the border of the actual and the imaginary."

Given the longstanding but limited readership for North American, Euro and Scandinavian e-lit, will Latin America succeed in carrying its experimental and avant-garde approaches to a general e-lit audience? Claudia Kozak's expanded keynote for the 2018 ELO conference in Montreal, titled "Mind the Gap!", explores some first forays in this direction: practices that might hearken back to Puig and Borges in print; Omar Goncedo, Eduardo Darino, Erthos Albino de Souza and Jesús Arellano in the era of mainframes; and (not least) fan fiction over pretty much the entire span of literary writing.

Image: Omar Gancedo, IBM (1966).

A conversation at a heightened level of intensity, ranging from the aleatory tradition of Emmett Williams, Jackson Mac Low, and John Cage, through post-Poundian poetry and its Chinese influences, kinetic poetry or programmable media where the poem itself is performing, not just the poet. Attention is also given to the Internet as these two literary artists knew it for a very brief moment, before Google and Facebook, circa 2004, "figured out that everybody needed an account."

2019

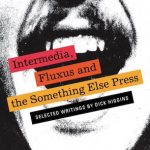

This review of Intermedia, Fluxus and the Something Else Press: Selected Writings by Dick Higgins, co-edited by Steve Clay and Ken Friedman, is itself a collaboration between Virginia Kuhn and Betsy Sullivan. Both approaches, to the review and the book here under consideration, capture the importance of community in creating and sustaining the art of Intermedia, Fluxus, and the Something Else Press.

Bouchardon and Petit defend the concept of digital writing and the teaching thereof. We can accept that digital writing exists, with its specific properties and tensions, but can it be taught? Specifically, the pedagogical dimension of what is known as "digital" writing, the authors argue, would do well to follow a study on the relationship between writing and computer science that was sponsored by the Picardy region : PRECIP, PRatiques d'ÉCriture Interactive en Picardie (interactive writing practices in Picardy).

This is an informal essay, not a paper. There are simply too many questions and few answers. The text was assembled from notes from my keynote conference at ELO 2018 in Montreal ("Mind the Gap!"), where I have experimented with a tentative form of performing theory, possibly pushing the limits of Walter Benjamin's desire to write a book made of quotations only. Also, as with all things, this is an incomplete account of the use of humor and constraint in electronic literature. Many examples just simply could not be included here, and it is not my intention to perform close-readings of any of these works either. My goal is simply to create a narrative that signals how humor is related to constraint in art and technology. Perhaps we can prepare an Anthology of Humorous Electronic Literature together? Also, some disambiguation is in order: this is not about computational humor, or the use of computers in humor research, or about jokes concerning computers. And this is also not about OuLiPo or other literary works specifically written under constraint.[footnote]For a discussion about these type of works, read ebr's thread "Writing Under Constraint," edited by Joseph Tabbi at the turn of the millennium. https://electronicbookreview.com/essay/writing-under-constraint/[/footnote]

Are digital practices ever going to transform what it means to create, circulate, read and preserve literary works? Bouchardon sets out ten ways that might happen.

What is the role of hand-crafted literary interfaces in a world of memes and bots? Kathi Inman Berens examines five recent books that address literary interfaces and applies pressure to the definition of "third generation electronic literature," exploring the role of code and intention in e-lit authorship.

Like e-books and so much else in digital commerce, the poetry printed out by Instagram give us back the book - stripping away the social features such as reader comments, nested conversations and responses that make a work "viral," or "spreadable." The content of Instagram poetry, to nobody's surprise, is almost always simplistic, inspirational, and emotional. What it spreads. like any other social media, is indistinguishable from from the surveillance infrastructure of digital metadata that allows algorithms to "read" the reader (who is left in the dark). Kathi Inman Berens in this essay puts forward some ways to change that.

Does literature have a place in a world of ubiquitous computing, massive user bases, and even larger audiences? It might, Flores suggests, but first we must redefine (and differently historicize) literary arts in ways that are not constricted by the print paradigm.

Here we transcribe an extended conversation between hypertext author Bill Bly and Ph.D. candidate Brian Davis that began in January 2018 at the Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities (MITH), home to The Bill Bly Collection of Electronic Literature. They discuss Bly's long-term electronic hypertext project, We Descend, Archives Pertaining to Egderus Scriptor (1997-present), as well as the history of electronic hypertext and hypertext theory, the technological challenges of born digital writing and archiving, book-archives and archival poetics, and the value of innovative writing and deep reading amidst the current century's "hodgepodge," "higgledy-piggledy" social media.

Through performances and readings configured across multiple screens, Phillippe Bootz conveys practices of constrained writing (and interrupted reading) into multiply mediated poetic dimensions.

A consideration of Monstrous Weather, a recent netprov (or networked improvisation) and the ways that collaborative storytelling encourages the rereading, retelling, rewriting, and adaptation of stories that begin as performances, and then turn into a form of archiving through still further rereading, rewriting and retelling. Author Alex Mitchell begins by depicting how, during the original performance of Monstrous Weather, there was a constant reworking, remixing and retelling of texts, both literally and through references and embellishments. This process gradually coalesced the loose collection of story fragments into something that had a kind of coherence, if not as a story, then at least as a storyworld. Mitchell discuss two particular performances/remixes: a live reading of excerpts from the netprov performed at the Electronic Literature Organization (ELO) Conference 2017 almost exactly 1 year after the initial performance, and a subsequent hypertext remix/archive.

An Mosaic for Convergence, Charles Bernstein's hypertext essay from ebr Issue 6 in the Winter of 1997-1998, explores the ramifications of a literature that is not structurally challenged, but structurally challenging. By then, Bernstein could sense a shift in literary sensibility, where it was beginning "to seem as natural to think of composing screen by screen rather than page by page." That was a few years after the flourishing of hypertext, but before the internet made reproduction of our print corpus a dominant practice (as e-books, primarily, with very little print/screen interplay or reader/author/programmer interchange). The moment Bernstein describes, and its instantiation on ebr's Alt-X legacy site, seems to the ebr editors something worth preserving - if only as a measure of recognized literary possibilities that have not been realized.

Bernstein's essay is the first of many that will be recovered by ebr co-editor Will Luers, and re-produced in the journal's version 7.0 (circa 2018-2019).

Babak Elahi shows how electronic literature in its public display, its interactivity, and its paradoxical combination of ephemerality and permanence brings us closer to the ancients than to the moderns - and closer still to the collective ritual experiences that Arabic and Muslim literature always valued over Western individualism. Further still, the emergence of Arabic e-lit does not just mean inclusions of still more cultural or ethnic identities. The politics of identity is yet another Western concern that an online Arabic poetics is happy to leave behind.

2018

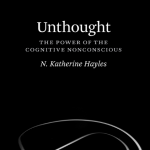

Cognition, as we've known for quite some time, is much larger than consciousness. And that realization can help explain literature's longtime, productive fascination with the unconscious. But today, when a scholar such as N. Katherine Hayles connects "nonconscious cognition to a wide range of technical, financial, and literary issues," we are set to fundamentally rethink the "nature and value of the humanities today."

At the moment when post-fictional fictions, essayistic fictions, and design fictions emerge as a cultural dominant, Rettberg, Swanstrom, Nesheim, Anderson and Pold discuss an emerging "aesthetics of infrastructure." Quietly condoned, mostly unnoticed installations of "Camouflaged Cell Concealment Sites" are now being visited by artists such as Betty Beaumont and Trevor Paglen. When our cloudy digital industries are so busily constructing cell phone towers that look like pine trees or Saguaro cactuses (sort of), the role of literary and visual artists may be simply to document these found fictions - for as long as they don't get arrested.

This conversation is published as the second in a series of texts centered around the publication of The Metainterface by Søren Pold and Christian Ulrik Andersen. Other essays in the series include: The Metainterface of the Clouds, Voices from Troubled Shores: Toxi•City: a Climate Change Narrative and Room for So Much World: A Conversation with Shelley Jackson.